Abstract

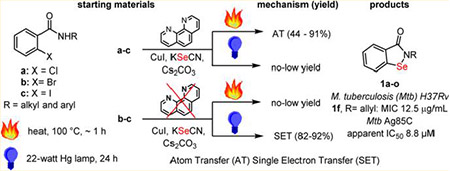

2-Alkyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones, represented by ebselen (1a), are being studied intensively for a range of medicinal applications. We describe both a new thermal and photoinduced copper-mediated cross-coupling between potassium selenocyanate (KSeCN) and N-substituted ortho-halobenzamides to form 2-alkyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones containing a C–Se–N bond. The copper ligand (1,10-phenanthroline) facilitates C–Se bond formation during heating via a mechanism that likely involves atom transfer (AT), whereas, in the absence of ligand, photoinduced activation likely proceeds through a single electron transfer (SET) mechanism. A library of 15 2-alkyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones was prepared. One member of the library was azide-containing derivative 1j that was competent to undergo a strain-promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition. The library was evaluated for inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) growth and Mtb Antigen 85C (Mtb Ag85C) activity. Compound 1f was most potent with a minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 12.5 μg/mL and an Mtb Ag85C apparent IC50 of 8.8 μM.

■ INTRODUCTION

2-Phenyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one (1a), also called ebselen, EBS, PZ51, and DR3305 (Figure 1), is a lipid soluble organo-selenium compound that mimics glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity and has the ability to inhibit some bacterial thioredoxin reductase systems (Figure 1).1–3 EBS is being studied as a possible therapeutic agent for cancer,4–8 bipolar disorder,9 and for a rapidly expanding list of other indications.10–14 Our interest was drawn to EBS due to our own efforts to identifying new Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) Ag85 inhibitors,15–19 by reports of its activity against Mtb Ag85C20 and drug-resistant Mtb.21 In this work, we develop an efficient method to prepare libraries of 2-alkyl-1,2-benziso-selenazol-3(2H)-ones in order to identify a lead candidate to for the treatment of Mtb infection.

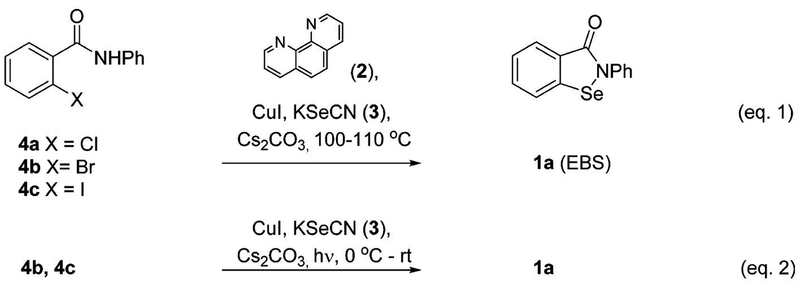

Figure 1.

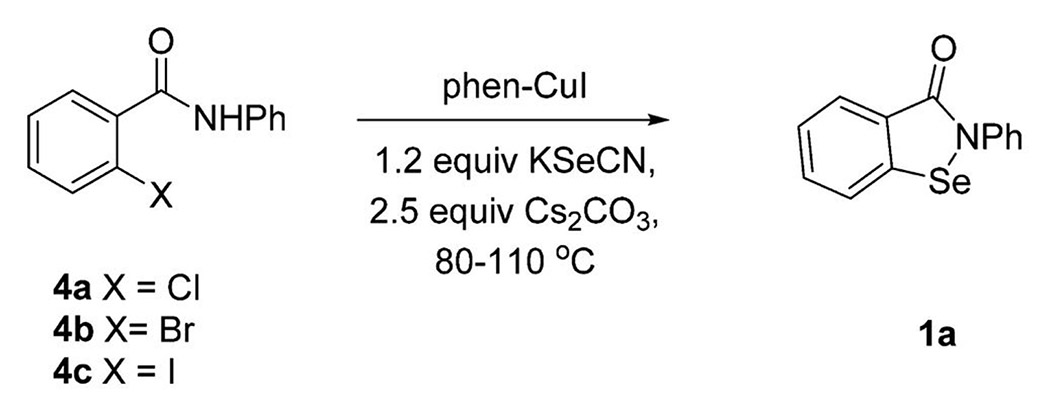

Thermal (eq 1) and photoinduced (eq 2) preparation of ebselen (1a).

Our efforts lead us to evaluate the contributions of a number of groups with regard to the preparation of EBS and its derivatives. The first report was in 1924 by Lesser and Weiss who started from 2-(hydroxyselanyl)cyclohexane-1-carbonyl chloride.22 Later, Welter et al. converted to anthranilic acid to 2,2′-diselanediyldibenzoic acid, followed by elaboration to EBS.23–32 Further, N-substituted benzamides have been treated with n-butyl lithium, Se powder, and CuBr to produce this chemotype.33–35 Kumar et al., accessed EBS using N-substituted ortho-halobenzamides catalytic CuI, 1,10-phenanthroline (2), Se powder, base, and heating for 8–36 h.36,37 The same group later accessed EBS using KSeOtBu,38 while Schinowski et al. used lithium diselenide and N-substituted ortho-iodobenzamides.39 In this work, we report that EBS and its derivatives can be prepared in as little as 1 h using CuI, 1,10-phenanthroline (2), KSeCN (3), and N-substituted ortho-halobenzamides (4a–c) (Figure 1, eq 1). In addition, we report a second method which represents the first example of a low temperature photoinduced copper-mediated cross-coupling of (4b–c) with KSeCN (3) to form a C–Se bond, leading to the formation of EBS (Figure 1, eq 2).

The discovery of a photoinduced copper-mediated cross-coupling for C–Se bonds also lead us to evaluate some of the key contributions to copper-mediated cross-coupling chemistry. The origins of this chemistry can be traced back to the early 1900s where Ullmann and Goldberg introduced copper as a catalyst for C–C and C–N bond formation. Within the last 20 years, there has been a resurgence in the use of copper with the development of new methods to allow the formation of other types C–N, C–O, C–S and C–Se bonds.40–43 The cross-coupling reactions reported to-date for C–Se bond formation require temperatures of greater than 100 °C.36,43,44 However, we took note of the work of Fu and Peters who reported photoinduced Cu-catalyzed cross-couplings to form C–S45 and C–N46,47 bonds at temperatures as low as 0 °C in seminal work which expanded the scope of Ullmann-type chemistry to thermally sensitive compounds.

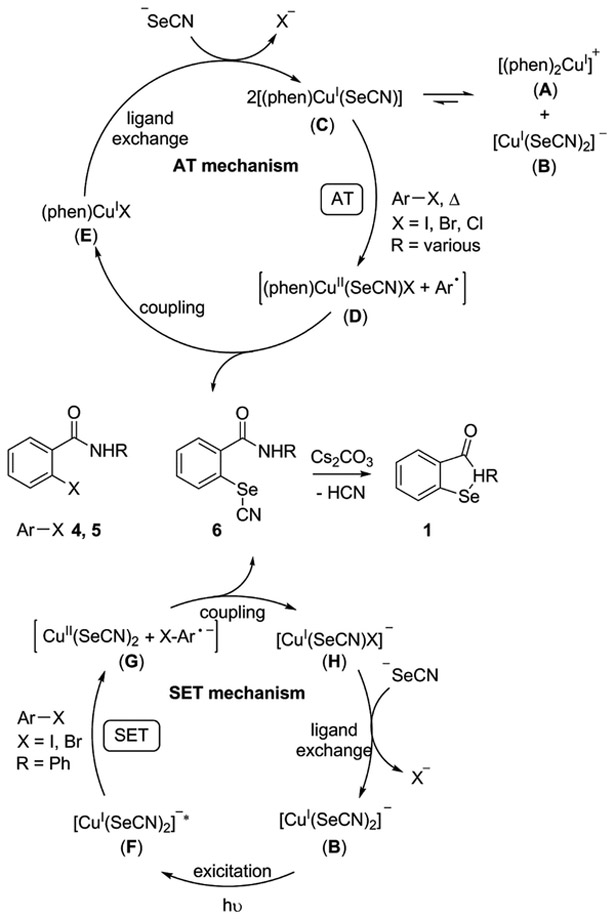

Herein, we introduce ligand-directed thermal and photoinduced Cu-promoted cross-coupling methods to form C–Se bonds in which the presence of ligand favors thermal activation via a putative atom transfer (AT) mechanism, whereas the absence of ligand favors photoinduced activation, which proceeds through a putative single electron transfer (SET) mechanism (Scheme 1). In this work, the C–Se bond formation results in a putative selenocyanate 6 which cyclizes to the medicinally important ebselen (1a) and its congeners in a single step.

Scheme 1.

Proposed Cu-Promoted Mechanisms for Thermal and Photoinduced Synthesis of 2-Alkyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-onesa

aAT = Atom transfer, SET = Single electron transfer.

■ RESULTS

Thermal Activation.

We initially explored synthesis of 2-alkyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones using reported conditions requiring 1,10-phenanthroline(phen)-CuI, Se-powder, potassium carbonate in combination with 4a to afford 1a; however, yields were modest in our hands after 30 h of heating (Table 1, entry 1).36,37 We noted that diaryl selenides have been successfully synthesized using phen-CuI in combination with KSeCN.48 On the basis of this observation, we surmised that the substitution of insoluble selenium power with KSeCN would produce an intermediate selenocyanate 6 that would cyclize to a selenazol-3(2H)-one under base-promoted conditions. Indeed, when we used aryl bromide 4b, KSeCN, 0.2 equiv of phen-CuI, and 2.5 equiv of Cs2CO3, we obtained similar yields to entry 1 (Table 1) with a significantly reduced reaction time (Table 1, entry 2). Furthermore, the reaction was homogeneous and convenient to work up. Increasing the phen-CuI to 0.30 equiv improved the yield to 34% and 53% at 1 and 12 h reaction times, respectively (Table 1, entries 3 and 4), while increasing the catalyst loading to 1.0 equiv resulted in a 71% yield in 1 h (Table 1, entry 5). The chloride 4a was less reactive, producing a 33% yield in 1.5 h under the same conditions (Table 1, entry 6), while the iodide 4c reacted quickly to produce 1a in 75% yield (Table 1, entry 7). Improved yields for the 4a were obtained by switching the solvent to acetonitrile (Table 1, entry 8). Aryl bromide 4b and aryl iodide 4c were converted to 1a using acetonitrile in 89% and 91% yields (Table 1, entries 9 and 10), respectively. DMSO could also be used as a solvent; however, yields were reduced (Table 1, entry 11). Further, we noted that 1,10-phenanthroline could be removed from the reaction to produce 1a; however, the yields were reduced (Table 1, entry 12).

Table 1.

Optimization of Thermal Method to Produce 2-Phenyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one (1a)a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | aryl halide |

phen-CuI (equiv) |

solvent | temp (°C) |

time (h) | yield (%) |

| 1b | 4a | 0.25 | DMF | 110 | 30 | 20 |

| 2 | 4b | 0.2 | DMF | 100 | 12 | 30 |

| 3 | 4b | 0.3 | DMF | 100 | 1 | 34 |

| 4 | 4b | 0.3 | DMF | 100 | 12 | 53 |

| 5 | 4b | 1.0 | DMF | 100 | 1 | 71 |

| 6 | 4a | 1.0 | DMF | 100 | 1.5 | 33 |

| 7 | 4c | 1.0 | DMF | 100 | 0.6 | 75 |

| 8 | 4a | 1.0 | CH3CN | 80 | 1 | 48 |

| 9 | 4b | 1.0 | CH3CN | 82 | 12 | 89 |

| 10 | 4c | 1.0 | CH3CN | 80 | 12 | 91 |

| 11 | 4b | 1.0 | DMSO | 100 | 1.5 | 44 |

| 12c | 4b | 1.0 | CH3CN | 82 | 12 | 41 |

Unless otherwise stated, 1.2 equiv of KSeCN and 2.5 equiv of Cs2CO3 were used.

Conditions used for comparison = Se powder, K2CO3 (3.0 equiv), CuI (25 mol %), phen (25 mol %).36

No phen, ambient light. The temperatures reported were measured outside the reaction vessel.

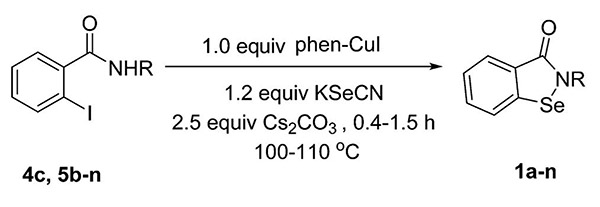

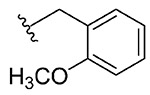

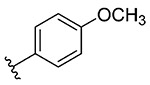

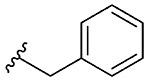

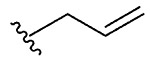

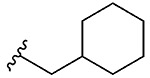

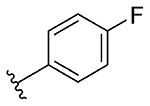

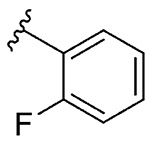

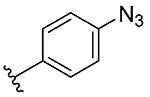

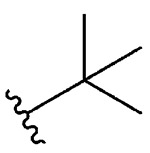

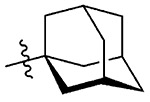

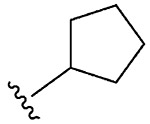

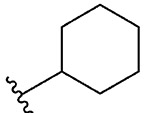

A library of 14 1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones was synthesized using this thermal method. The members of the library differ from each other at the nitrogen substituent (Table 2). Compounds 1a, 1d, 1h, 1i, and 1j were prepared with a phenyl group or an ortho- or para-substituted phenyl group (i.e., substituents = fluoro, methoxy, or azide) as the nitrogen substituent. Compounds 1b, 1c, and 1e contained a benzyl substituent, while compound 1f possessed an allyl substituent. Aliphatic substituents were also tolerated as demonstrated by the preparation of compounds 1g, 1m, and 1n, which contain aliphatic rings. Larger substituents were tolerated such as tert-butyl and adamantyl, as shown by the preparation of compounds 1k and 1l, respectively.

Table 2.

Thermal Synthesis of a 1,2-Benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one Library

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | R | product, yield (%) |

| 1 | 4c |  |

1a, 91 |

| 2 | 5b |  |

1b, 63 |

| 3 | 5c |  |

1c, 44 |

| 4 | 5d |  |

1d, 67 |

| 5 | 5e |  |

1e, 39 |

| 6 | 5f |  |

1f, 39 |

| 7 | 5g |  |

1g, 63 |

| 8 | 5h |  |

1h, 52 |

| 9 | 5i |  |

1i, 35 |

| 10 | 5j |  |

1j, 23 |

| 11 | 5k |  |

1k, 75 |

| 12 | 5l |  |

1l, 72 |

| 13 | 5m |  |

1m, 78 |

| 14 | 5n |  |

1n, 85 |

Photoinduced Activation.

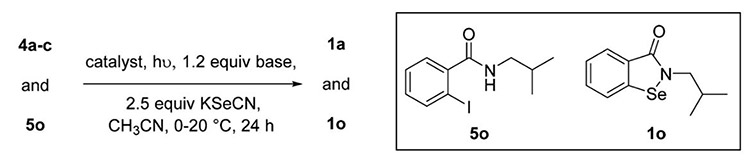

We were intrigued by a report from Fu et al. that shows Ullmann-type reactions occur under photoinduced conditions in the absence of a copper ligand.45 Therefore, we explored this possibility with KSeCN and aryl halides (4a–c) to form ebselen (1a). Table 3 shows our results using aryl bromide (4b) which affords 1a in 89% using thermal conditions (entry 1). Replacing the heating with a 22 W (combined) Hg lamp (Figure S1) and cooling with ice for 2 h, following by warming to room temperature, afforded 1a in 31% (Table 3, entry 2). A significant improvement in the yield to 82% occurred when the 1,10-phenanthroline ligand was removed from the reaction (Table 3, entry 3). This data supports a proposed mechanism in which a [(phen)CuI-(SeCN)] (C) complex is needed in the thermal activation method, however, not needed in the light activated case. The yield of the photoinduced reaction dropped to 60% and 0% when 10 and 0 mol % CuI were used (Table 3, entries 4 and 5, respectively). These results illustrate the requirement for copper(I). When the phen-free reaction was placed in the dark, a 6% yield was observed (Table 3, entry 6), indicating the importance of light. Removal of the base (Table 3, entry 7) resulted in no reaction. Ambient light was sufficient to generate a 21% yield (Table 3, entry 8). Use of a 250 W IR lamp produced a 63% yield; however, moderate heating (65–70 °C) was also involved (Table 3, entry 9). Finally, the combination of 10 mol % CuI and NaOtBu afforded a yield of 81%; however, the reaction time was extended to 48 h (Table 3, entry 10). Iodide 4c was a superior substrate in the reaction; however, chloride 4a was unreactive (Table 3, entries 11 and 12, respectively). The chemistry was also successful for alkyl amide 5o which afforded ebselen derivative 1o in 85% yield. An additional reaction was conducted using only the shortwave UV light (RPR-3000A lamp, 250–360 nm), indicating that the BLE-8T365 lamp (320–400 nm) was not needed for the reaction (Table 3, entry 14). In summary, the combination of light, a phen-free Cu(I) source, and base promoted efficient formation of ebselen (1a). This is the first report of a photoinduced copper-promoted C–Se–N bond forming reaction.

Table 3.

Optimization of Photoinduced Method To Produce 2-Phenyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-onesa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | equiv, catalyst | halogen | energy | yield (%) |

| 1 | 1.0, phen-CuI | 4b | thermal reaction | 1a: 89b |

| 2 | 1.0, phen-CuI | 4b | 22 W Hg lamp | 1a: 31 |

| 3 | 1.0, CuI | 4b | 22 W Hg lamp | 1a: 82 |

| 4 | 0.1, CuI | 4b | 22 W Hg lamp | 1a: 60c |

| 5 | 4b | 22 W Hg lamp | 1a: N.R. | |

| 6 | 1.0, CuI | 4b | dark | 1a:6 |

| 7 | 1.0, CuI | 4b | 22 W Hg lamp | 1a: N.R. |

| 8 | 1.0, CuI | 4b | ambient light | 1a: 21 |

| 9 | 1.0, CuI | 4b | 250 W infrared lamp | 1a: 63d |

| 10 | 0.1, CuI | 4b | 22 W Hg lamp | 1a: 81c,e |

| 11 | 1.0, CuI | 4c | 22 W Hg lamp | 1a: 92 |

| 12 | 1.0, CuI | 4a | 22 W Hg lamp | 1a: N.R. |

| 13 | 1.0, CuI | 5o | 22 W Hg lamp | 1o: 85 |

| 14 | 1.0, CuI | 4b | 14 W Hg lamp | 1a: 77f |

Unless otherwise stated, KSeCN (2.5 equiv) and Cs2CO3 (1.2 equiv) 24 h, and acetonitrile were used. Reactions were cooled for about 2 h and allowed to warm to room temperature (20 °C).

Thermal activation = phen-CuI (1.0 equiv), KSeCN (1.2 equiv), Cs2CO3 (2.5 equiv), 12 h, 100–110 °C.

48 h.

Reaction reached 65–70 °C.

NaOtBu (0.1 equiv). N.R = no reaction. 22 W is a combined wattage of two lamps.

Reaction performed without BLE-8T365 (320–400 nm) lamp; only the 14 W Rayonet RPR-3000A lamp was used.

Copper Species Study.

We investigated the identity of possible copper complexes that might be present under thermal conditions by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). For the thermal case, a mixture of CuI, phen, KSeCN, and Cs2CO3 (1.0:1.0:1.2:2.5) in acetonitrile was heated to 70–80 °C for 1 h, followed by ESI-MS. Major cationic species were detected at m/z: 423.2 and 425.1, which correspond to [(phen)2Cu63]+ and [(phen)2Cu65]+ (A), respectively (Supporting Information, Figure S2). ESI-MS in the negative ion mode was inconclusive. For the photoinduced case, a mixture of CuI, KSeCN, and Cs2CO3 (1.0:2.2:1.2) in acetonitrile, which lacks phen, was irradiated with a 22 W (combined) Hg lamp at room temperature for 1 h. ESI-MS was inconclusive in the positive ion mode; however, the negative ion mode revealed major masses at m/z: 272, 274, and 276 that were assigned to the isotope envelope of [Cu(SeCN)2]−, i.e., [Cu63(Se80CN)2]−, [Cu63(Se80CN)(Se78CN)]−, and [Cu65(Se80CN)2]− (B), respectively (Supporting Information, Figure S3). The absorption spectrum of the CuI, KSeCN, and Cs2CO3 (1.0:2.2:1.2) mixture was recorded after irradiation. The sample had a strong absorption band at 242 nm, and the sample exhibited a strong fluorescence emission at 338 nm after excitation at 242 nm (Supporting Information, Figure S4). The absorption spectra of a mixture of complex B (0.91 μM) + 4b (0.91 μM) and compound 4b (0.91 μM) alone were obtained for characterization purposes (Supporting Information, Figure S5). To provide evidence of that photoexcited complex B can transfer energy to the substrate, substrate 4b was titrated into complex B and the luminescence recorded, revealing strong concentration-dependent fluorescence quenching (Supporting Information, Figure S6).

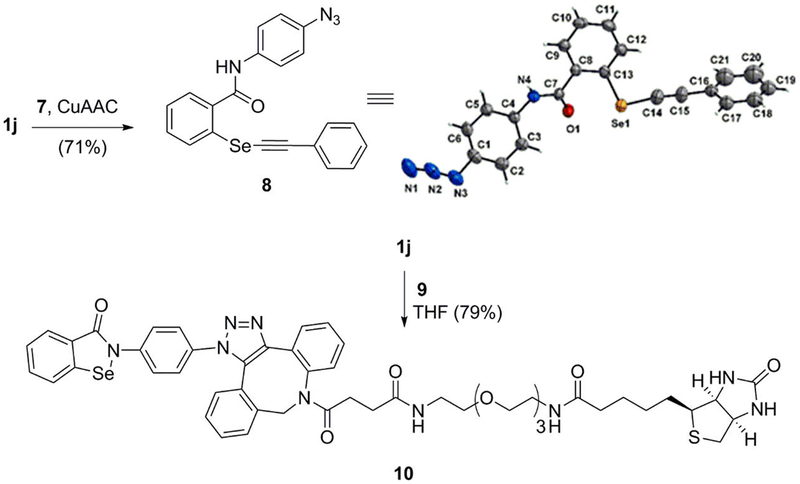

Synthesis of Biotinylated 1,2-Benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones.

Our interest in 1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones was sparked by the cysteine-reactive nature of ebselen (1a) against an Mtb Ag85C20 as well as reports of activity against other cysteine-containing enzymes.49 New tools are needed to identify other possible cysteine-reactive targets within Mtb and other organisms. Our method development was driven in part by a desire to access 1j which could potentially be used in combination with click chemistry as part of a long-term goal to identify cysteine-reactive enzymes and proteins. Once in hand, we investigated whether azide 1j would undergo the copper-promoted azide–alkyne Huisgen cycloaddition (CuAAC). Thus, azide 1j was treated with phenylacetylene (7) under standard CuAAC conditions. However, instead of forming the 1,2,3-triazole, phenylacetylene opened the selenazol-3(2H)-one ring to afford the isobaric dialkyl selenide (8). The formation of compound 8 was is confirmed by X-ray crystallography (Scheme 2). In retrospect, the identification of adduct 8 is not surprising since Cu(I) is known to form Cu-acetylides.50 These intermediates can attack the Se atom in 1,2-benziso-selenazol-3(2H)-ones. To circumvent this problem, 1j was treated with dibenzocyclooctyne-PEG3-biotin (9) in THF to afford triazole 10 in 79% yield. Compound 10 may serve as a useful affinity-based tool for identification of enzymes with solvent exposed cysteines.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 2-Phenylbiotinyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one 10 and X-ray Crystal Structure of N-(4-Azidophenyl)-2-((phenylethynyl)selanyl)benzamide (8)

Mtb Growth and Enzyme Inhibition Studies.

The library of 16 1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones was screened against Mtb H37Rv using a modified 96-well microplate Alamar blue assay (MABA) to determine minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs). The MICs ranged from 12.5 to 100 μg/mL with the exception of compound 10, which was less active (Table 4). The library was screened at 5 μM for the ability to covalently inhibit the activity of Mtb Ag85C using a previously reported fluorometric assay.20 Mtb Ag85C is involved in the biosynthesis of the Mtb cell wall,51 and EBS has been shown to inhibit Mtb Ag85C by forming a selenenylsulfide bond at Cys209.20 On the basis of the activity of EBS, it was expected that some members of this library would behave similarly. The percent of Mtb Ag85C activity remaining after 40 min of incubation ranged from 15% to 80% for the library (Table 4;Supporting Information, Figure S7). The same assay20 was used to determine the apparent IC50 (appIC50) for each compound against Mtb Ag85C after 15 min of incubation. This assay revealed appIC50 in the range of 0.54 to greater than 100 μM (Table 4; Supporting Information, Figure S8A and S8B).

Table 4.

Activity of 2-Alkyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones against Mtb H37Rv and Mtb Ag85C

| compound no. | cLogPa | MIC (μg/mL) | Mtb Ag85C activity (%)b | Ag85C appIC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 3.70 | 12.5 | 17 ± 3 | 5.12 |

| 1b | 3.65 | 25 | 24 ± 17 | 0.54 |

| 1c | 3.65 | 12.5 | 36 ± 4 | 28.6 |

| 1d | 3.62 | 25 | 20 ± 4 | 1.2 |

| 1e | 3.73 | 25 | 20 ± 10 | 6.5 |

| 1f | 2.73 | 12.5 | 15 ± 2.0 | 8.8 |

| 1g | 4.60 | 50 | 30 ± 16 | 5.3 |

| 1h | 3.85 | 25 | 19 ± 2 | 0.72 |

| 1i | 3.85 | 25 | 21 ± 7 | 1.0 |

| 1j | 4.15 | 25 | 20 ± 4 | 1.1 |

| 1k | 3.20 | 25 | 31 ± 12 | 1.5 |

| 1l | 4.62 | 50 | 59 ± 14 | 25 |

| 1m | 3.43 | 25 | 40 ± 17 | 4.1 |

| 1n | 3.99 | 25 | 44 ± 15 | 3.7 |

| 8 | 5.76 | 100 | 80 ± 7 | >100 |

| 10 | 5.26 | N/A | 61 ± 11 | 2.02 |

clogP was calculated using ChemBioDraw Ultra 13.

The percent activity of Mtb Ag85C was determined after treatment with 5 μM inhibitor and 40 min of preincubation. The activity was normalized to an untreated (uninhibited) control reaction. The error was calculated by performing each reaction in triplicate.

■ DISCUSSION

Chemistry.

Different mechanisms have been proposed for the copper-catalyzed Ullmann-type reactions.52–62 These include (i) oxidative addition—reductive elimination (OA-RE, Cu(I)/(III)),57,63 (ii) single-electron transfer (SET, Cu(I)/(II)),56 and (iii) atom transfer (AT, Cu(I)/(II)).62 An OA-RE cycle involves oxidative addition of Ar-X on LCuI(SeCN) to generate an LCuIII(SeCN)ArX intermediate, which undergoes RE to form a C–Se coupled product. The work of Mitani,64 Bethell,65 Hartwig,66 and Huffman67 suggested the possible occurrence of Cu(III) species. However, more recent computational studies by Jones et al. suggest the energies required to access the Cu(III) species in the OA step are prohibitively high in comparison to energies required for key intermediates in SET and AT mechanisms.68 We propose AT and SET mechanisms for the arylselenocyanate formation in Scheme 1. The AT mechanism involves transfer of the halide atom from aryl halide to a (phen)CuI(SeCN) (C) complex, forming caged aryl radical (Ar·) and (phen)CuII(SeCN)X complex (D). Complex (D) would couple to afford an arylselenocyanate 6 and (phen)CuIX (E). Intermediate E can undergo ligand exchange to regenerated C, completing the cycle. Arylselenocyanate 6 can cyclize to form 1. A photoinduced SET mechanism requires a radical-nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SRN1) and involves photoexcitation of [CuI(SeCN)2]− (B) to afford excited species [CuI(SeCN)2]−* (F), which can undergoes SET to form a putative caged radical pair comprising [Ar–X•− and CuII(SeCN)2] (G).68 Intermediate G can couple to form arylselenocyanate 6 and [CuI(SeCN)X]− (H). Intermediate H can undergo ligand exchange to regenerate B, completing the catalytic cycle. The radicals generated in the SET and AT mechanisms are proposed to exist as caged radical pairs which rapidly convert to product; hence, they are not affected in the presence of radical quenchers.69,70 EPR spectroscopy studies by Hida and co-workers on the reaction of haloanthraquinones and aminoethanol observed the short-lived radical species and Cu(II) species.69,70 Similarly, Fu and Peters observed copper(II)-thiolate complexes during studies on photoinduced cross-coupling between aryl thiols and aryl halides.71 We also note the order of reactivity of aryl halides for C–Se cross-coupling under the thermal and photoinduced conditions was I > Br > Cl, which parallels the reduction potentials of aryl halides (e.g., PhI −1.91 V, PhBr −2.43 V, PhCl −2.76 V)72,73 and is opposite to the reactivity of aromatic nucleophilic substitution reaction. This also infers that the thermal reaction proceeds through a radical reaction.

The observed and proposed intermediates parallel what has been observed for the Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling of aryl halides with thiols both thermally and photoinduced. For the thermal case, Hartwig et al. used X-ray diffraction and solution phase characterization to observe copper complexes that exist as neutral three-coordinate trigonal planar complexes of [(phen)CuI(phth)] in the solid state and as ionic complexes consisting of [(phen)2CuI]+ and [Cu(phth)2]− in solution.66 Hartwig et al. also isolated ionic complexes (e.g., [(Me2phen)2-Cu]+ and [Cu(OPh)2]−) in the copper-catalyzed etherification of aryl halides and observed that the concentration of ionic complexes is higher in polar solvents.66 We postulate the presence of a related neutral [(phen)CuI(SeCN)] (C) intermediate in the thermally activated copper-promoted cross-coupling to form C–Se bonds. This adduct can form from the disproportionation reaction of [(phen)2CuI]+ (A) and [CuI(SeCN)2]− (B) complexes. Our evidence for this intermediate is indirectly supported by the observation that addition of ligand increases the yield from 44% to 89% (Table 1, entries 11 and 9). Only the addition of ligand would allow for formation of a [(phen)CuI(SeCN)] (C) or a related neutral (phen) complex. For the photoinduced case, Peters and Fu extensively investigated the cross-coupling between and thiols and aryl halides. They concluded that the [Cu(SAr)2]− anion is the lone and active intermediate.71 Similarly, we observed the related [Cu(SeCN)2]− (B) anion. EPR studies by Hida and coworkers on the photoinduced Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling of haloanthraquinones and aminoethanol identified short-lived radical species and Cu(II) species.69,70 Similarly, Fu and Peters observed copper(II)-thiolate complexes (analogous to complex G) during studies on photoinduced cross-coupling between and thiols and aryl halides.71 We set up experiments with and without 1,10-phenanthroline ligand. Under photoinduced activation, addition of ligand decreases yield from 82% to 31% (Table 3, entries 3 and 2), which is likely a result of a decrease in [CuI(SeCN)2]− concentration, indicating [CuI(SeCN)2]− as active catalyst. Our observations combined with the cited prior work suggests that the photoinduced Cu-promoted cross-coupling of arylhalides and KSeCN proceeds through an SET mechanism.

Biological.

Among the library, compound 1a, 1c, and 1f showed the lowest MICs = 12.5 μg/mL against Mtb H37Rv and shared calculated LogP (cLogP) values in the range of 2.73–3.70. Compounds 1g, 8, and 10 showed MIC ≥ 50 μg/mL and shared cLogP values ≥ 4.60. The remainder of the compounds shared intermediate MICs and cLogP values. We suspect the most active compounds had cLogP values ideal for cell wall diffusion. Compounds 1a, 1c, and 1f reduced Mtb Ag85C activity to 17%, 36%, and 15%, respectively, after 40 min of enzyme incubation (Table 4). Compounds 1g, 1l, 1m, 1n, 10 reduced Mtb Ag85C activity to 30%, 59%, 40%, 44%, and 61%, respectively. This reduction in compound activity between the two groups loosely correlates with the replacement of the phenyl group with an alkyl or the large biotinyl moiety in the case of 10. The data suggest all the compounds were reacting with the exposed cysteine 209 on Mtb Ag85C; however, the phenyl-containing compounds accessed the reactive site better. This conclusion is supported by the appIC50 data which show all the compounds with the exception of 8 rapidly inactivate the enzyme at low concentrations.74 The results are significant in light of limited progress that has been made identifying inhibitors of Ag85s. The few classes of compounds have been described which inhibit the Ag85s have been reviewed75 and include thiophenes,17,76 phosphonates,77 sulfonates,78 and derivatives of trehalose51,79,80 and arabino-sides.19,81 These earlier inhibitors demonstrated IC50s in the mid to low μM range, whereas, in the current study, we identified inhibitors in the nM range.

CONCLUSIONS

An efficient Cu-promoted synthesis of 2-alkyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones was discovered that involves the use of 1,10-phenanthroline, KSeCN, and ortho-halobenzamides. The method affords the products in as little as 1 h, which is significantly faster than similar chemistry using Se powder. As part of this study, the first example of a photoinduced Cu-promoted C–Se bond forming reaction was discovered that enabled the synthesis of ebselen (1a) at low temperatures upon irradiation with a 22 W (combined) Hg lamp. An atom transfer step and a 1,10-phenanthroline-Cu complex is proposed in the thermal mechanism, and a single electron transfer step is proposed for the photoinduced mechanism. The mechanisms are supported by the ESI-MS detection of [(phen)2CuI]+ (A) and [CuI(SeCN)2]− (B) complexes. A library of 14 1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones was prepared in good yield using the thermal method. The library was evaluated for anti-Mtb H37RV activity and the ability to inhibit a cysteine-containing Mtb Ag85C demonstrating different aspects of utility for the chemotype. As a result, new Mtb growth and enzyme inhibitors were identified. Due to the rapidly expanding medical applications for 2-alkyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones, these methods are expected to facilitate the synthesis of new therapeutics.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Information.

All the starting materials were obtained from Acros Organics or Sigma-Aldrich. Unless specified, all the reactions are carried out under an atmosphere of nitrogen using a nitrogen balloon. All solvents were purchased form Fisher Scientific or Sigma-Aldrich. The solvents were purified by distillation and other standard methods. Reactions were monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC silica gel 62 F254), and spots were observed by UV light. All photochemical reactions were carried out in a handmade cardboard box fitted with two bulbs with a combined output of 22 W (14 W Rayonet RPR-3000A lamp (spectral energy distribution wavelength range: 250–360 nm) + 8 W Spectronics Corp. BLE-8T365 (365 nm)). An Aminco Bowman II luminescence spectrometer was used for fluorimetry experiments. 1H NMR and 13C NMR and G-COSY were carried out using a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz or Varian Inova 600 MHz spectrometers. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were referenced to the CDCl3 peak at 7.27 and 77.16, respectively. High resolution mass spectroscopy (HRMS) was performed on a micro mass Q-TOF2 instrument.

General Procedure for Thermal Activated Synthesis of Benzo-1,2-selenazol-3(2H)-one compounds, Table 1.

The starting benzamide (1 equiv), copper(I) iodide (1 equiv), 1,10-phenanthroline (1 equiv), cesium carbonate (2.5 equiv), and potassium selenocyanate (1.2 equiv) were suspended in solvent N,N-dimethylmethanamide or acetonitrile. The resulting red colored mixture was heated to 95–100 °C for 0.6–12 h. The reaction was cooled, diluted with 20.0 mL of ethyl acetate, and filtered, and the residue was washed with ethyl acetate. To the filtrate was added cold H2O (20.0 mL), followed by extraction with 20.0 mL of ethyl acetate. This process was repeated thrice. The combined ethyl acetate extracts were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated to obtain a solid which was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (ethyl acetate–hexane) to obtain product 1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one derivative.

Synthesis of 2-Phenylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1a).82

2-Iodo-N-phenylbenzamide (400 mg, 1.24 mmol), copper(I) iodide (236 mg, 1.24 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (223 mg, 1.24 mmol), cesium carbonate (1011 mg, 3.10 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (214 mg, 1.49 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 45 min, 100 °C. Purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (35% ethyl acetate–hexanes) to obtained pure 2-phenylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one 1a. Yield 75% (256.2 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.37 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 182–183 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.13 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.70–7.62 (m, 4 H), 7.49 (ddd, J = 2.3, 5.8, 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.47–7.42 (m, 2 H), 7.32–7.28 (m, J =1.0, 1.0 Hz, 1 H) ; 13C NMR (150.2 MHz, MeoD) δ 166.6, 139.7, 139.0, 132.2, 129.0, 128.0, 127.9, 126.7, 126.1, 125.5, 124.8; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C13H17NO3Na 297.9747; Found 297.9748.

Synthesis of 2-(4-Methoxybenzyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1b).

2-Iodo-N-(4-methoxybenzyl)benzamide (400 mg, 1.08 mmol), copper(I) iodide (207 mg, 1.08 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (196 mg, 1.08 mmol), cesium carbonate (888 mg, 2.72 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (188 mg, 1.30 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 1 h, 100 °C. Purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (35% ethyl acetate–hexane) to obtain pure 2-(4-methoxybenzyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1b). Yield 63% (220.5 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.1 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 139–141 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.08 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.59–7.54 (m, 9 H), 7.43 (ddd, J = 2.6, 5.6, 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.33–7.30 (m, J = 8.6 Hz, 8 H), 6.92–6.89 (m, 2 H), 4.96 (s, 2 H), 3.82 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (150.2 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.1, 159.8, 139.3, 132.0, 130.3, 129.5, 129.0, 127.9, 126.3, 124.1, 114.3, 55.5, 48.4; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C15H13NO2SeNa 342.0004; Found 342.0016.

2-(2-Methoxybenzyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1c).

2-Iodo-N-(2-methoxybenzyl)benzamide (370 mg, 1.01 mmol), copper(I) iodide (192 mg, 1.01 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (182 mg, 1.01 mmol), cesium carbonate (821 mg, 2.52 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (174 mg, 1.20 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 1 h, 100 °C. Purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (25% ethyl acetate–hexane) to obtain pure product 2-(2-methoxybenzyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1c). Yield 44% (141 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.24 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 169–170 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.08 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 5 H), 7.58–7.56 (m, 10 H), 7.44–7.40 (m, J = 1.7 Hz, 11 H), 7.34 (dt, J =1.7, 7.8 Hz, 6 H), 6.99–6.91 (m, J = 0.9, 7.4, 7.4 Hz, 11 H), 5.07 (s, 2 H), 3.93 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (150.2 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.6, 138.6, 131.9, 131.0, 130.0, 128.9, 127.6, 126.1, 125.7, 123.9, 121.0, 110.6, 55.4, 43.6; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C15H13NO2SeNa 342.0009; Found 342.0017.

Synthesis of 2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1d).39

2-Iodo-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)benzamide (400 mg, 1.13 mmol), copper(I) iodide (216 mg, 1.13 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (204 mg, 1.33 mmol), cesium carbonate (922 mg, 2.83 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (196 mg, 1.30 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 1 h, 100 °C. Purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (35% ethyl acetate–hexane) to obtain pure product 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1d). Yield 67% (231 mg), pale yellow solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.25 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 170–171 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.12 (td, J = 0.9, 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.65–7.68 (m, 2H), 7.46–7.53 (m, 3H), 6.94–6.98 (m, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (150.2 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.1, 158.6, 137.9, 132.5, 131.7, 129.5, 127.6, 127.4, 126.6, 132.9, 114.7, 55.7; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C14H11NO2SeNa 327.9847; Found 327.9858.

Synthesis of 2-Benzylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one(1e).36

N-Benzyl-2-iodobenzamide (276 mg, 0.88 mmol), copper(I) iodide (156 mg, 0.82 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (148 mg, 0.82 mmol), cesium carbonate (667 mg, 2.04 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (142 mg, 1.20 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 1 h, 100 °C. Purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (25% ethyl acetate–hexane) to obtain pure product 2-benzylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1e). Yield 39% (90 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.28 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 130–132 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.60 (m, J = 0.7 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (ddd, J = 2.7, 5.4, 7.9 Hz, 1h), 7.33–7.39 (m, 5H), 5.03 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (150.2 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.2, 138.0, 137.2, 132.0, 129.0, 128.9, 128.6, 128.4, 127.4, 126.3, 124.0, 49.0; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C14H11NOSeNa 311.9898; Found 311.9914.

Synthesis of 2-Allylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1f).

2-Iodo-N-allylbenzamide (400 mg, 1.39 mmol), copper(I) iodide (267 mg, 1.39 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (251 mg, 1.39 mmol), cesium carbonate (1.135 g, 3.48 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (241 mg, 1.67 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 1.5 h, 100 °C. Purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (25% ethyl acetate–hexane) to obtain pure product 2-allylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-x3(2H)-one (1f). Yield 39% (90 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.28 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 124–126 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.08 (qd, J = 0.7, 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.67–7.64 (m, 1 H), 7.63–7.59 (m, 1 H), 7.45 (ddd, J = 1.0, 7.0, 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 5.99 (tdd, J = 6.3, 10.2, 16.9 Hz, 1 H), 5.44–5.31 (m, 2 H), 4.50 (td, J = 1.3, 6.4 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (150.2 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.1, 138.0, 133.7, 132.1, 129.0, 127.8, 126.3, 124.1, 119.5, 47.3; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C10H9NOSeNa 261.9742; Found 261.9755.

Synthesis of 2-(Cyclohexylmethyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1g).

N-(Cyclohexylmethyl)-2-iodobenzamide (200 mg, 0.58 mmol), copper(I) iodide (110 mg, 0.58 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (105 mg, 0.58 mmol), cesium carbonate (474.66 mg, 1.45 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (100 mg, 0.70 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 1.5 h, 100 °C. After flash column chromatography on silica gel using 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes as mobile phase, pure product 2-(cyclohexylmethyl)benzo[d][1,2]-selenazol-3(2H)-one (1g) was obtained. Yield 63% (110 mg), off-white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.59 (1:1 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 151–152 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.07 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.66–7.59 (m, 2 H), 7.47–7.43 (m, 1 H), 3.73 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.82–1.73 (m, 5 H), 1.69 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 1.31–1.18 (m, 3 H), 1.12–1.03 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (150.2 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.4, 137.8, 131.9, 128.9, 127.5, 126.2, 123.9, 59.5, 50.9, 39.1, 31.3, 30.6, 26.3, 25.7; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C14H17NOSeNa 318.0368; Found 318.0381.

Synthesis of 2-(4-Fluorophenyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1h).

N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-iodobenzamide (400 mg, 1.17 mmol), copper(I) iodide (335 mg, 1.76 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (317 mg, 1.79 mmol), cesium carbonate (995.56 mg, 2.93 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (203 mg, 1.40 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 1 h, 100 °C. After flash column chromatography on silica gel using 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes as mobile phase, pure product 2-(4-fluorophenyl)benzo[d][1,2]-selenazol-3(2H)-one (1h) was obtained. Yield 52% (180 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.15 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 176–177 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.13 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 2H), 7.56–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.46–7.52 (m, 1H), 7.11–7.18 (m, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.8, 160.94 (d, J = 247.6 Hz), 137.47, 134.77 (d, J = 3.30 Hz), 132.6, 129.4, 127.49 (d, J = 7.7 Hz), 127.0, 126.6, 123.7, 116.2 (d, J = 22.0 Hz); HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C13H8FNOSeNa 315.9647; Found 315.9657.

Synthesis of 2-(2-Fluorophenyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1i).

N-(2-Fluorophenyl)-2-iodobenzamide (400 mg, 1.17 mmol), copper(I) iodide (335 mg, 1.76 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (317 mg, 1.79 mmol), cesium carbonate (995.56 mg, 2.93 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (203 mg, 1.40 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 1 h, 100 °C. After flash column chromatography on silica gel using 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes as mobile phase, pure product 2-(2-fluorophenyl)benzo[d][1,2]-selenazol-3(2H)-one (1i) was obtained. Yield 35% (120 mg), off-white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.24 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 156–158 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.04–7.97 (m, J = 7.3 Hz, 2 H), 7.82–7.73 (m, 2 H), 7.54–7.49 (m, J = 1.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.43–7.39 (m, J = 1.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.38–7.31 (m, J = 1.2, 7.6 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 117.18 (d, J = 19.8 Hz), 122.1, 123.9, 125.11 (d, J = 3.3 Hz), 130.7, 130.9, 131.13 (d, J = 6.6 Hz), 132.7, 133.7, 158.44 (dd, J = 250.8, 1.0 Hz), 166.4; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C13H8FNOSeNa 315.9647; Found 315.9657.

Synthesis of 2-(4-Azidophenyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1j).

N-(4-Azidophenyl)-2-iodobenzamide (500 mg, 1.37 mmol), copper(I) iodide (262 mg, 1.37 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (247 mg, 1.37 mmol), cesium carbonate (1118 mg, 3.43 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (237 mg, 1.40 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (5.0 mL), 1 h, 90 °C. After flash column chromatography on silica gel using 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes as mobile phase, pure product 2-(4-azidophenyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1j) was obtained. Yield 20% (90 mg), brown solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.24 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 169–170 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.14 (td, J = 0.9, 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.71–7.67 (m, 2 H), 7.66–7.63 (m, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.51 (ddd, J = 3.7, 4.5, 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.14–7.09 (m, J = 8.8 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (150.2 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.8, 138.4, 137.4, 135.9, 132.7, 129.5, 127.2, 127.0, 126.7, 123.8, 119.8; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C13H8N4OSeNa 338.9756; Found 338.9763.

Synthesis of 2-(tert-Butyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1k).39

N-(tert-Butyl)-2-iodobenzamide (200.0 mg, 0.66 mmol), copper(I) iodide (126 mg, 0.66 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (119 mg, 0.66 mmol), cesium carbonate (538 mg, 1.65 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (114 mg, 0.79 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (2.0 mL), 1 h, 90 °C. After flash column chromatography on silica gel using 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes as mobile phase, pure product 2-(tert-butyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1k) was obtained. Yield 75% (125 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.43 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 137–139 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ (td, J = 1.1, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.60 (m, 2H), 7.40 (ddd, J = 1.7, 6.3, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 1.69 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.1, 137.0, 131.7, 130.2, 128.5, 126.1, 123.3, 59.0, 29.2; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C11H14NOSe 256.0235; Found 256.0233.

Synthesis of 2-((3R,5S)-Adamantan-1-yl)benzo[d][1,2]-selenazol-3(2H)-one (1l).

N-((3R,5S)-Adamantan-1-yl)-2-iodobenzamide (400.0 mg, 1.04 mmol), copper(I) iodide (200 mg, 1.04 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (189 mg, 1.04 mmol), cesium carbonate (855 mg, 2.62 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (182 mg, 1.26 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 1 h, 90 °C. After flash column chromatography on silica gel using 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes as mobile phase, pure product 2-((3R,5S)-adamantan-1-yl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1l) was obtained. Yield 72% (250 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.51 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 215–217 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.97 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.58 (m, 1H), 7.57–7.54 (m, 1H), 7.41–7.38 (m, 1H), 2.43 (d, J= 2.4 Hz, 6H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 1.81–1.79 (m, 3H), 1.75–1.73 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (150.2 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.8, 137.5, 131.5, 130.5, 128.5, 126.0, 123.4, 60.1, 41.7, 36.4, 30.3; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C17H20NOSe 334.0705; Found 334.0722.

Synthesis of 2-Cyclopentylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1m).

N-Cyclopentyl-2-iodobenzamide (350.0 mg, 1.11 mmol), copper(I) iodide (211.6 mg, 1.11 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (200.2 mg, 1.11 mmol), cesium carbonate (905 mg, 2.77 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (192.1 mg, 1.33 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (3.0 mL), 1 h, 90 °C. After flash column chromatography on silica gel using 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes as mobile phase, pure product 2-cyclopentylbenzo[d][1,2] selenazol-3(2H)-one (1m) was obtained. Yield 78% (232 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.23 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 119–120 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.03–8.05 (m, 1H), 7.62–7.64 (m, 1H), 7.57 (dt, J = 1.4, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (ddd, J =1.0, 7.1, 7.9 Hz, 1H), (quin, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 2.17–2.27 (m, J= 1.6, 2.8 Hz, 2H), 1.81–1.90 (m, 1H), 1.69–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.61–1.68 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.2, 137.5, 133.2, 131.7, 128.6, 126.2, 123.8, 55.9, 33.5, 24.2; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/zxs: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C12H13NOSeNa 290.0055; Found 290.0058.

Synthesis of 2-Cyclohexylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1n).39

N-Cyclohexyl-2-iodobenzamide (400.0 mg, 1.21 mmol), copper(I) iodide (231.6 mg, 1.22 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (219.1 mg, 1.21 mmol), cesium carbonate (990.3 mg, 3.04 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (210.2 mg, 1.45 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (4.0 mL), 1 h, 90 °C. After flash column chromatography on silica gel using 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes as mobile phase, pure product 2-cyclohexylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1n) was obtained. Yield 85% (290 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.27 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 157–158 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10–7.99 (m, 1 H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.57 (s, 1 H), 7.42 (s, 1 H), 4.53–4.45 (m, 1 H), 2.11 (dd, J = 2.0, 12.7 Hz, 2 H), 1.87 (d, J = 13.9 Hz, 2 H), 1.77–1.70 (m, 1 H), 1.50 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.40 (dd, J = 3.7, 11.7 Hz, 2 H), 1.25–1.16 (m, 1 H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.6, 137.9, 137.9, 131.7, 128.8, 126.2, 124.0, 53.8, 34.4, 25.6. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C13H16NOSe 282.0392; Found 282.0392.

Synthesis of N-(4-Azidophenyl)-2-((phenylethynyl)selanyl)-benzamide (8).

2-(4-Azidophenyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (100.0 mg, 0.32 mmol), copper(I) iodide (60.27 mg, 0.32 mmol), 1,10-phenanthroline (57.0 mg, 0.32 mmol), cesium carbonate (257.8 mg, 0.79 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (54.7 mg, 0.38 mmol), and N,N-dimethylmethanamide (1.5 mL), 1 h, 90 °C. After flash column chromatography on silica gel using 35% ethyl acetate in hexanes as mobile phase, pure product N-(4-azidophenyl)-2-((phenylethynyl)selanyl)benzamide (8) was obtained. Yield 71% (93.7 mg), brown solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.26 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) 8.33 (dd, J = 0.9, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.73 (dd, J = 1.3, 7.70 Hz, 1H), 7.62–7.67 (m, 2H), 7.55–7.59 (m, 3H), 7.37–7.42 (m, 4H), 7.05–7.10 (m, 2h); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.7, 136.8, 135.5, 134.3, 132.8, 132.0, 131.0, 130.7, 128.7, 128.5, 126.7, 126.4, 123.4, 122.3, 119.8, 104.5, 73.8; HRMS (ESI-MS) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C21H14N4OSeNa 441.02; Found 441.02.

Synthesis of N-(13,16-Dioxo-16-(3-(4-(3-oxobenzo[d][1,2]-selenazol-2(3H)-yl)phenyl)-3,9-dihydro-8H-dibenzo[b,f][1,2,3]-triazolo[4,5-d]azocin-8-yl)-3,6,9-trioxa-12-azahexadecyl)-5-((3aS,6aR)-2-oxohexahydro-1H-thieno[3,4-d]imidazol-4-yl)-pentanamide (10).

In a dried round-bottom flask, 2-(4-azidophenyl)benzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (10.0 mg, 0.032 mmol) was dissolved in dry THF (0.5 mL) under a N2 atmosphere and stirred for 5.0 min. Then, the solution of dibenzocyclooctyne-PEG3-biotin (9, 22.32 mg, 0.032 mmol) was added and reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12.0 h. After reverse phase column chromatography using H2O as mobile phase, pure product compound 10 was obtained. Yield 79% (25.6 mg), ash color solid. Note: 1H NMR integration values were not clear due to complexity of molecule, but C13 and HRMS were clear. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.08–8.15 (m, 1H), 7.74–7.87 (m, 4H), 7.61–7.72 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.59 (m, 6H), 7.30–7.39 (m, 2H), 7.02–7.07 (m, 1H), 6.92–7.01 (m, 1H), 6.75 (s, 1H), 6.20–6.28 (m, 1H), 5.66–5.79 (m, 1H), 4.97–5.08 (m, 1H), 4.45–4.52 (m, 2H), 4.29–4.38 (m, 1H), 3.61 (br. s., 4H), 3.53–3.59 (m, 6H), 3.46–3.52 (m, 4H), 3.35–3.42 (m, 2H), 3.23–3.32 (m, 2H), 3.06–3.18 (m, 2H), 2.85–2.96 (m, 1H), 2.65–2.75 (m, 1H), 2.33–2.46 (m, 2H), 2.13–2.25 (m, 2H), 2.02 (s, 1H), 1.37–1.50 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.0, 172.1, 172.0, 165.9, 163.1, 144.1, 143.2, 140.6, 140.3, 133.7, 132.9, 131.6, 131.2, 129.8, 129.3, 129.1, 128.7, 127.9, 127.8, 127.6, 127.5, 127.2, 126.7, 125.8, 125.5, 125.2, 124.9, 124.7, 124.2, 124.0, 70.3, 61.7, 59.9, 55.2, 52.2, 40.6, 39.3, 39.2, 39.2, 39.1, 35.6, 35.0, 30.7, 29.6, 27.9, 27.2, 25.4. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C50H55N9O8SSeNa 1044.2952; Found 1044.2976.

General Procedure for Photoinduced Synthesis of Benzo-1,2-selenazol-3(2H)-ones.

A borosilicate tube under an atmosphere of nitrogen was charged with aryl halide (1.0 equiv), CuI (1.0 equiv), KSeCN (2.5 equiv), Cs2CO3 (1.2 equiv), and acetonitrile (3.0 mL). The tube was sealed with a rubber septum, and the heterogeneous reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C with vigorous stirring. The cooled tube was irradiated by the 22 W Hg lamps for 12–24 h. After the reaction was complete, it was filtered through Celite, and washed with ethyl acetate. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel, 30% ethyl acetate in hexanes.

Photoinduced Synthesis of 2-Phenylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1a).

Using 2-iodo-N-phenylbenzamide (4c, 100 mg, 0.31 mmol), copper(I) iodide (59.0 mg, 0.31 mmol), cesium carbonate (121 mg, 0.37 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (112 mg, 0.78 mmol), and acetonitrile (3.0 mL), 16 h, 0 °C to room temperature. Purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (35% ethyl acetate–hexane) to obtain pure 2-phenylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1a). Yield 92% (78.3 mg); silica gel TLC Rf = 0.37 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes). Using 2-bromo-N-phenylbenzamide (4b, 100 mg, 0.36 mmol), copper(I) iodide (69.2 mg, 0.36 mmol), cesium carbonate (142 mg, 0.44 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (131 mg, 0.91 mmol), and acetonitrile (3.0 mL), 16 h, 0 °C to room temperature. Purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (35% ethyl acetate–hexane) to obtain pure 2-phenylbenzo[d][1,2]-selenazol-3(2H)-one (1a). Yield 87% (87.2 mg); silica gel TLC Rf = 0.37 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes). Using 2-chloro-N-phenylbenzamide (4a, 100 mg, 0.31 mmol), copper(I) iodide (59.0 mg, 0.31 mmol), cesium carbonate (121 mg, 0.37 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (112 mg, 0.78 mmol), and acetonitrile (3.0 mL), 16 h, 0 °C to room temperature. Purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (35% ethyl acetate–hexane) to obtain pure 2-phenylbenzo[d][1,2]-selenazol-3(2H)-one (1a). Yield < 5; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.37 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes).

Photoinduced Synthesis of 2-Isobutylbenzo[d][1,2]-selenazol-3(2H)-one (1o).

2-Iodo-N-isobutylbenzamide (200 mg, 0.66 mmol), copper(I) iodide (126 mg, 0.66 mmol), cesium carbonate (258 mg, 0.79 mmol), potassium selenocyanate (237 mg, 1.65 mmol), and acetonitrile (3.0 mL), 32 h, 0 °C to room temperature. Purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (30% ethyl acetate–hexane) to obtain pure 2-isobutylbenzo[d][1,2]selenazol-3(2H)-one (1o). Yield 85% (143.8 mg), white solid; silica gel TLC Rf = 0.39 (3:7 ethyl acetate–hexanes); mp 114–116 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.06 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.62–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.57–7.62 (m, 1H), 7.43 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.05 (quind, J = 13.7 Hz, 1H), 1.00 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.5, 137.9, 132.0, 129.0, 127.6, 126.3, 124.0, 52.2, 30.1, 20.1; HRMS (ESI-MS) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C11H14NOSe 256.0235; Found 256.0240.

Synthesis of Thermal Activated Copper Complex [(phen)2-CuI]+ [CuI(SeCN)2]− (A and B).

A 50.0 mL round-bottom flask (RBF) was charged with CuI (50 mg, 0.26 mmol), phen (47.3 mg, 0.26 mmol), KSeCN (95 mg, 0.65 mmol), Cs2CO3 (102.64 mg, 0.31 mmol), and acetonitrile (2.0 mL) under an atmosphere of N2. The resulting red colored reaction mixture was heated to 80 °C for 1.0 h, and then it was filtered through a plug of Celite to obtain copper complex A and B.

Synthesis of Copper Complex [CuI(SeCN)2]− (B).

A borosilicate tube was charged with CuI (50 mg, 0.26 mmol), KseCN (95 mg, 0.65 mmol), Cs2CO3 (102.64 mg, 0.31 mmol), and acetonitrile (2.0 mL) under an atmosphere of N2. The tube was sealed with a rubber septum, and the heterogeneous mixture was cooled to 0 °C. The cooled tube with reaction mixture was irradiated with a 22 W Hg lamp for 1 h, and then it was filtered through a short plug of Celite to obtain copper complex B.

Steady-State Fluorimetry Experiment on Copper Complex B.

A 26 μM solution of complex B in acetonitrile was excited using a Xe arc lamp (500 W) at 242 nm, and the right angle emission was detected at 338 nm (Figure S4).

Absorption Spectrum of Complex B, Mixture of B and 4b, and Compound 4b.

Copper complex [CuI(SeCN)2]− (B) at 5.25 μM, complex B (5.25 μM) plus 4b (0.91 μM), and compound 4b (0.91 μM, alone) were prepared. The absorption spectra were then recorded (Figure S5).

Luminescence Quenching of Complex B.

2.0 mL of 5.25 μM copper complex [CuI(SeCN)2]− (B) in acetonitrile was transferred into a standard quartz cuvette. The cuvette was placed in an Aminco Bowman II Spectrofluorometer, and complex B was excited at a wavelength of 242 nm. The emission spectrum was recorded, revealing an emission at 338 nm. Compound 4b was added to the cuvette at concentrations of 0.72, 1.45, 2.18, and 2.90 μM, and the change in intensity of the emission spectra was recorded (Figure S6).

Procedure To Determine Percent Mtb A85C Active after 40 min of Incubation with Inhibitors.

Ag85C was expressed and purified as previously described.83 The enzyme was reacted with 5 μM of 1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one 1a–1n, 8, and 10 (10 mM DMSO stock) for 40 min at room temperature. The enzymatic activity of Ag85C, covalently modified with these analogues, was evaluated using a fluorometric assay previously described (Figure S7).20 Briefly, resorufin butyrate was used as an acyl donor while trehalose was utilized as the acyl acceptor. All reactions were performed in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5). Trehalose was dissolved in the reaction buffer to produce a 500 mM stock, while a 10 mM stock solution of resorufin butyrate was prepared using DMSO. The reactions were performed in triplicate at 37 °C on a Synergy H4 Hybrid Reader (BioTek) using 500 nM Ag85C, 4 mM trehalose, and 100 μM resorufin butyrate. Reactions are initiated through the addition of resorufin butyrate. Analysis of the data was carried out using Prism 5 software (Figure S7).

Procedure To Determine Apparent IC50 of 1,2-Benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-ones against Mtb Ag85C.

An apparent IC50 value for each 1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one was obtained for Mtb Ag85C by varying the concentration of inhibitor, ranging from 40.0 μM to 312.0 nM (Figure S8A and S8B). Compounds were incubated with Ag85C for 15 min at room temperature. Enzymatic activity was assessed using the resourifin butyrate assay previously described. The apparent IC50 was calculated using the following equation: IC50 = [(50 – A)(B – A)] × (D – C) + C,84 where points were expressed in percent inhibition: (i) A = the point on the curve that is less than 50%, (ii) B = the point on the curve that is greater than or equal to 50%, (iii) C = the concentration of inhibitor that gives the A% inhibition, and (iv) D = the concentration of inhibitor that gives the B% inhibition (Figure S8A and S8B).

In Vitro Mtb Alamar Blue Assay (MABA).

Mtb H37Rv is a drug sensitive laboratory reference strain used in the MIC studies.85 The bacteria were grown at 37 °C in Difco 7H9 Middlebrook liquid media (BD Biosciences, 271310) supplemented with 10% Middlebrook OADC Enrichment, 0.05% Tween (G-Biosciences, 786–519) and 0.2% Glycerol. A modified 96-well microplate Alamar Blue assay (MABA) was used to establish MIC values.86 Briefly, compounds were solubilized in DMSO and were 2-fold serially diluted in 7H9 media (DMSO < or equal to 0.02% DMSO). Bacteria were grown to mid-log growth, diluted, and added to the wells with compounds. Cell and media controls were included in each plate. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 6 days when Alamar blue was added to each well, and then the plate was incubated overnight (Alamar blue final concentration 0.001%). On day seven, the last well that showed no sign of growth and remained blue was considered the MIC for that compound.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. AI105084) to S.J.S. and D.R.R. We thank Kelly J. Lambright of the University of Toledo Instrumentation Center for assistance with X-ray crystallography on compound 8.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.7b00440.

1H, 13C NMR spectra for new compounds, compound 8 X-ray statistics, fluorescence studies, Mtb Ag85C study data, Alamar Blue assay (PDF) Crystallographic data for compound 8 (CIF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Müller A; Cadenas E; Graf P; Sies H Biochem. Pharmacol 1984, 33, 3235–3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wendel A; Fausel M; Safayhi H; Tiegs G; Otter R Biochem. Pharmacol 1984, 33, 3241–3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Steinbrenner H; Steinbrenner H; Bilgic E; Steinbrenner H; Bilgic E; Alili L; Sies H; Brenneisen P Free Radical Res 2006, 40, 936–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Yan J; Guo Y; Wang Y; Mao F; Huang L; Li X Eur. J. Med. Chem 2015, 95, 220–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Xing F; Li S; Ge X; Wang C; Zeng H; Li D; Dong L Oral Oncol 2008, 44, 963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Zeng H; Combs GF J. Nutr. Biochem 2008, 19, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sanmartín C; Plano D; Sharma AK; Palop JA Int. J. Mol. Sci 2012, 13, 9649–9672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Huawei Z; Gerald FC Jr. J. Nutr. Biochem 2008, 19, 1–7.17588734 [Google Scholar]

- (9).Singh N; Halliday AC; Thomas JM; Kuznetsova OV; Baldwin R; Woon ECY; Aley PK; Antoniadou I; Sharp T; Vasudevan SR; Churchill GC Nat. Commun 2013, 4, 1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Rusetskaya NY; Borodulin VB Biochemistry(Moscow, Russ. Fed.) 2015, 9, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ding H; Wang T; Xu D; Cha B; Liu J; Li Y Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2015, 460, 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Petronilho F; Florentino D; Silvestre F; Danielski LG; Nascimento DZ; Vieira A; Kanis LA; Fortunato JJ; Badawy M; Barichello T; Quevedo J Inflammation 2015, 38, 1394–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tan SM; Deliyanti D; Figgett WA; Talia DM; de Haan JB; Wilkinson-Berka JL Exp. Eye Res 2015, 136, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Vichi S; Cortés-Francisco N; Caixach J Food Chem 2015, 175, 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Boucau J; Sanki AK; Sucheck SJ; Ronning DR 235th National Meeting Abstr. Pap. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, BIOL-058. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Boucau J; Sanki AK; Voss BJ; Sucheck SJ; Ronning DR Anal. Biochem 2009, 385, 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ibrahim DA; Boucau J; Lajiness DH; Veleti SK; Trabbic KR; Adams SS; Ronning DR; Sucheck SJ Bioconjugate Chem 2012. 23, 2403–2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sanki AK; Boucau J; Ronning DR; Sucheck SJ Glycoconjugate J 2009, 26, 589–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Sanki AK; Boucau J; Umesiri FE; Ronning DR; Sucheck SJ Mol. BioSyst 2009, 5, 945–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Favrot L; Grzegorzewicz AE; Lajiness DH; Marvin RK; Boucau J; Isailovic D; Jackson M; Ronning DR Nat. Commun 2013, 4, 2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Padiadpu J; Baloni P; Anand K; Munshi M; Thakur C; Mohan A; Singh A; Chandra N ACS Infect. Dis 2016, 2, 592–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lesser R; Weiß R Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. B 1924, 57, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Welter A; Christiaens L; Wirtz P; Nattermann A, und Cie. G.m.b.H., Fed. Rep. Ger. Patent EP0044453 (A2), 1982; p 30.

- (24).Młochowski J; Kloc K; Syper L; Inglot AD; Piasecki E Eur. J. Org Chem 1993, 1993, 1239–1244. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Fong MC; Schiesser CH Tetrahedron Lett 1995, 36, 7329–7332. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Mlochowski J; Juchniewicz L; Kloc K; Gryglewski RJ; Jakubowski A; Inglot AD Eur. J. Org. Chem 1996, 1996, 1751–1755. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Osajda M; Młochowski J Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 7531–7537. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wojtowicz H; Chojnacka M; Młochowski J; Palus J; Syper L; Hudecova D; Uher M; Piasecki E; Rybka M Farmaco 2003, 58, 1235–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kloc K; Maliszewska I; Mlochowski J Synth. Commun 2003, 33, 3805–3815. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wojtowicz H; Kloc K; Maliszewska I; Mlochowski J; Pietka M; Piasecki E Farmaco 2004, 59, 863–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Pietka-Ottlik M; Wojtowicz-Mlochowska H; Kolodziejczyk K; Piasecki E; Mlochowski J Chem. Pharm. Bull 2008, 56, 1423–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Pietka-Ottlik M; Potaczek P; Piasecki E; Mlochowski J Molecules 2010, 15, 8214–8228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Engman L; Hallberg AJ Org. Chem 1989, 54, 2964–2966. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Chang T; Huang M; Hsu W; Hwang J; Hsu L Chem. Pharm. Bull 2003, 51, 1413–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zade SS; Panda S; Singh HB; Wolmershaeuser G Tetrahedron Lett 2005, 46, 665–669. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Balkrishna SJ; Bhakuni BS; Chopra D; Kumar S Org. Lett 2010, 12, 5394–5397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Balkrishna SJ; Bhakuni BS; Kumar S Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 9565–9575. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Balkrishna SJ; Kumar S; Azad GK; Bhakuni BS; Panini P; Ahalawat N; Tomar RS; Detty MR; Kumar S Org. Biomol. Chem 2014, 12, 1215–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Pacula AJ; Scianowski J; Aleksandrzak KB RSC Adv 2014, 4, 48959–48962. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Ullmann F; Bielecki J Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges 1901, 34, 2174–2185. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Ullmann F; Sponagel P Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges 1905, 38, 2211–2212. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Lee C; Liu Y; Badsara SS Chem. - Asian J 2014, 9, 706–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Beletskaya IP; Ananikov VP Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 1596–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Kumar AV; Reddy VP; Reddy CS; Rao KR Tetrahedron Lett 2011, 52, 3978–3981. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Uyeda C; Tan Y; Fu GC; Peters JC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 9548–9552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Ziegler D. l. T.; Choi J; Munoz-Molina JM; Bissember AC; Peters JC; Fu GC J.Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 13107–13112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Do H; Bachman S; Bissember AC; Peters JC; Fu GC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 2162–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Beletskaya IP; Sigeev AS; Peregudov AS; Petrovskii PV; Khrustalev VN Chem. Lett 2010, 39, 720–722. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Bender KO; Garland M; Ferreyra JA; Hryckowian AJ; Child MA; Puri AW; Solow-Cordero DE; Higginbottom SK; Segal E; Banaei N; Shen A; Sonnenburg JL; Bogyo M Sci. Transl Med 2015, 7, 306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Hein JE; Fokin VV Chem. Soc. Rev 2010, 39, 1302–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Belisle JT; Vissa VD; Sievert T; Takayama K; Brennan PJ; Besra GS Science 1997, 276, 1420–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Cohen T; Lewarchik RJ; Tarino JZJ Am. Chem. Soc 1974, 96, 7753–7760. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Cohen T; Cristea IJ Am. Chem. Soc 1976, 98, 748–753. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Weingarten H J. Org. Chem 1964, 29, 3624–3626. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Aalten HL; van Koten G; Grove DM; Kuilman T; Piekstra OG; Hulshof LA; Sheldon RA Tetrahedron 1989, 45, 5565–5578. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Bunnett JF; Kim JKJ Am. Chem. Soc 1970, 92, 7463–7464. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Jenkins CL; Kochi JK J. Am. Chem. Soc 1972, 94, 856–865. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Litvak VV; Shein SM Zh. Org. Khim 1974, 10, 2360–2364. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Bacon RGR; Hill HA O. J. Chem. Soc 1964, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Whitesides GM; Fischer WF Jr.; San Filippo J Jr.; Bashe RW; House HO J. Am. Chem. Soc 1969, 91, 4871–4882. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Whitesides GM; Kendall PE J. Org. Chem 1972, 37, 3718–3725. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Johnson CR; Dutra GA J. Am. Chem. Soc 1973, 95, 7783–7788. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Kochi JK J. Am. Chem. Soc 1957, 79, 2942–2948. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Mitani M; Kato I; Koyama KJ Am. Chem. Soc 1983, 105, 6719–6721. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Bethell D; Jenkins IL; Quan PM J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1985, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Tye JW; Weng Z; Johns AM; Incarvito CD; Hartwig JF J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 9971–9983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Huffman LM; Stahl SS J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 9196–9197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Jones GO; Liu P; Houk KN; Buchwald SL J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 6205–6213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Arai S; Hida M; Yamagishi T Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1978, 51, 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- (70).Arai S; Yamagishi T; Ototake S; Hida M Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1977, 50, 547–548. [Google Scholar]

- (71).Johnson MW; Hannoun KI; Tan Y; Fu GC; Peters JC Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 4091–4100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Enemaerke RJ; Christensen TB; Jensen H; Daasbjerg K J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 2001, 1620–1630. [Google Scholar]

- (73).Creutz SE; Lotito KJ; Fu GC; Peters JC Science 2012, 338, 647–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Goins CM; Dajnowicz SJ; Thanna S; Sucheck SJ; Parks JM; Ronning D R ACS Infect. Dis 2017, DOI: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Thanna S; Sucheck SJ MedChemComm 2016, 7, 69–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Warrier T; Tropis M; Werngren J; Diehl A; Gengenbacher M; Schlegel B; Schade M; Oschkinat H; Daffe M; Hoffner S; Eddine AN; Kaufmann SHE Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2012, 56, 1735–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Gobec S; Plantan I; Mravljak J; Wilson RA; Besra GS; Kikelj D Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2004, 14, 3559–3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Kovac A; Wilson RA; Besra GS; Filipic M; Kikelj D; Gobec S J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem 2006, 21, 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Rose JD; Maddry JA; Comber RN; Suling WJ; Wilson LN; Reynolds RC Carbohydr. Res 2002, 337, 105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Wang J; Elchert B; Hui Y; Takemoto JY; Bensaci M; Wennergren J; Chang H; Rai R; Chang CWT Bioorg. Med. Chem 2004, 12, 6397–6413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Sanki AK; Boucau J; Srivastava P; Adams SS; Ronning DR; Sucheck S J. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2008, 16, 5672–5682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Fischer H; Dereu N Bull. Soc. Chim. Belg 1987, 96, 757–768. [Google Scholar]

- (83).Favrot L; Lajiness DH; Ronning DR J. Biol. Chem 2014, 289, 25031–25040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Optimization in Drug Discovery; Yan Z; Caldwell GW Eds.; Humana Press, 2014, ISBN: 978–1-62703–741-9. [Google Scholar]

- (85).Knudson SE; Kumar K; Awasthi D; Ojima I; Slayden RA Tuberculosis 2014, 94, 271–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Kumar K; Awasthi D; Lee SY; Zanardi I; Ruzsicska B; Knudson S; Tonge PJ; Slayden RA; Ojima I J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 374–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.