Abstract

T cells expressing CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) produce high remission rates in B-cell lymphoma, but frequent disease recurrence and challenges in generating sufficient numbers of autologous CAR-T cells necessitate the development of alternative therapeutic effectors. Vα24-invariant natural killer T cells (NKTs) have intrinsic anti-tumor properties and are not alloreactive, allowing for off-the-shelf use of CAR-NKTs from healthy donors. We recently reported that CD62L+ NKTs persist longer and have more potent anti-lymphoma activity than CD62L− cells. However, the conditions governing preservation of CD62L+ cells during NKT-cell expansion remain largely unknown. Here, we demonstrate that IL-21 preserves this crucial central-memory-like NKT subset and enhances its anti-tumor effector functionality. We found that following antigenic stimulation with α-galactosylceramide, CD62L+ NKTs both expressed IL-21R and secreted IL-21, each at significantly higher levels than CD62L− cells. Although IL-21 alone failed to expand stimulated NKTs, combined IL-2/IL-21 treatment produced more NKTs and increased the frequency of CD62L+ cells versus IL-2 alone. Gene expression analysis comparing CD62L+ and CD62L− cells treated with IL-2 alone or IL-2/IL-21 revealed that the latter condition downregulated pro-apoptotic protein BIM selectively in CD62L+ NKTs, protecting them from activation-induced cell death. Moreover, IL-2/IL-21-expanded NKTs upregulated granzyme B expression and produced more TH1 cytokines, leading to enhanced in vitro cytotoxicity of non-transduced and CD19-CAR-transduced NKTs against CD1d+ and CD19+ lymphoma cells, respectively. Further, IL-2/IL-21-expanded CAR-NKTs dramatically increased the survival of lymphoma-bearing NSG mice compared to IL-2-expanded CAR-NKTs. These findings have immediate translational implications for the development of NKT-cell-based immunotherapies targeting lymphoma and other malignancies.

Introduction

T cells engineered to express chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) that target the CD19 antigen have substantially improved outcomes in patients with B cell malignancies, particularly acute lymphoblastic leukemia (1). However, CAR-T cells are less effective against non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with less than half of patients achieving durable complete responses (2). Moreover, T cells obtained from lymphoma patients, particularly children, have been shown to possess reduced proliferative potential and consequently produce limited cell numbers when expanded ex vivo (3). Thus, there is an urgent need to develop alternative strategies for CAR-redirected immunotherapy.

Several allogeneic CAR-T cell-based therapeutic approaches have been developed to promote anti-lymphoma activity and minimize the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). For example, donor-derived virus-specific T cells engineered to express anti-CD19 CAR (CD19-CAR) undergo expansion early after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and produce objective responses without causing GVHD (4). However, with the exception of malignancies caused by Epstein-Barr virus, virus-specific T cells are not inherently tumor-reactive, and their anti-tumor potential depends entirely on the specificity of the CAR, which can be circumvented by escape variants. Due to these limitations, other lymphocyte subsets, such as NK, γδ T, and natural killer T (NKT) cells have been tested. These cells have inherent anti-tumor properties and can be safely infused into immunosuppressed individuals without causing GVHD (5, 6).

Type 1 NKTs are an evolutionarily conserved subset of innate lymphocytes characterized by expression of invariant TCR α-chain Vα24-Jα18 and reactivity to glycolipids presented by the HLA class-I-like molecule CD1d (7). CD1d is widely expressed by both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cell types including monocytes, primitive hematopoietic stem cells, thymocytes, keratinocytes, hepatocytes, and both normal and malignant B cells (8). It is also found on the surface of tumor-associated macrophages (9), which are associated with poor outcome in lymphoma (10). Unlike HLA molecules, CD1d is monomorphic with the result that NKTs are not alloreactive; indeed, allo-HSCT mouse model studies suggest that NKTs suppress GVHD and enhance the graft-versus-leukemia effect (11). Importantly, reconstitution of peripheral blood NKTs has been associated with long-term remission in pediatric leukemia patients receiving haploidentical transplants (12). Thus, NKTs possess natural anti-tumor effector functions and can be generated from healthy donors for off-the-shelf use.

While NKTs are found at low frequency in human peripheral blood, we have developed methods for clinical scale CAR-NKT-cell production (NCT03294954) (13, 14). Generation of large numbers of NKTs for clinical applications requires robust ex vivo expansion while simultaneously preserving cell functionality and longevity. Repeated stimulation and extended culture of T cell therapeutic products, for example, have been associated with exhaustion, poor in vivo persistence, and limited objective responses in cancer patients (15). Conversely, a higher frequency of central-memory phenotype cells in T cell therapy products has been linked with more potent therapeutic activity in pre-clinical models and clinical trials (15, 16).

Despite significant progress delineating NKT-cell development and maintenance in mice (17), the homeostatic requirements for human NKTs remain largely unexplored, particularly in the context of therapeutic applications. Unlike peripheral blood T cells, freshly isolated NKTs do not have a clear hierarchy of naïve-central-effector differentiation and instead display an effector-memory-like phenotype (18). However, we recently reported that NKT-cell ex vivo expansion in response to stimulation with specific antigen α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer) resulted in accumulation of CD62L+ central-memory-like cells, which were found to be progressively lost upon subsequent TCR stimulation (14). Importantly, when NKTs were transduced with a CD19-CAR, only the CD62L+ subset induced long-term disease-free survival in lymphoma-bearing NOD/SCID/IL-2Rγnull (NSG) mice (14), indicating that maintenance of the central-memory-like phenotype is critical for generating effective, long-acting NKT-cell-based therapies.

Our initial analysis of immune-related genes differentially expressed in CD62L+ versus CD62L− NKT subsets revealed significantly higher levels of IL-7R and IL-21R mRNA expression in the former (14), suggesting that IL-7 and/or IL-21 may support central-memory-like differentiation and superior therapeutic activity of NKTs. IL-7 and IL-21 play important roles at different stages of B, T, and NKT-cell development and function (19, 20). While IL-7R deficiency impacts development of T and NKT cells similarly (21), a recent report showed that IL-21/IL-21R-induced Stat3 signaling is selectively required for NKT development in humans (22). However, the role of IL-21 in supporting differentiation and maintenance of central-memory-like NKTs has not been examined. In this study, we evaluated the effects of IL-21 on the number, phenotype, and functional properties of ex vivo-expanded NKTs and CAR-NKTs. Our results demonstrate that IL-21 selectively protects CD62L+ NKTs from activation-induced cell death (AICD) by downregulating expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bcl-2-like protein 11 (BIM). Moreover, IL-21 supports expansion of highly cytotoxic, TH1-polarized CAR-NKTs that promote long-term survival of lymphoma-bearing mice.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

K562, Daudi, Raji, Ramos, and 293T cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The B-8–2 clone of the K562 cell line was derived previously in our lab (14). All lines except 293T were cultured in RPMI (HyClone, Logan, UT); 293T cells were maintained in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM; HyClone). Both types of medium were supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and 2mM GlutaMAX™-I (Gibco, Waltham, MA).

NKT cell isolation, transduction, expansion, and sorting

Peripheral blood of healthy donors was purchased from Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from buffy coats by density gradient centrifugation. NKTs were purified using anti-iNKT microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), and the negative PBMC fraction was irradiated (40 Gy) and aliquoted. NKTs were stimulated with an aliquot of autologous PBMCs pulsed with α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer, 100 ng/ml; Kyowa Hakko Kirin). The culture was supplemented every other day with recombinant IL-2 (200 U/ml; National Cancer Institute Frederick), recombinant IL-7 (10 ng/ml; PeproTech) and/or recombinant IL-21 (10 ng/ml; PeproTech), where indicated, in complete RPMI (HyClone RPMI 1640, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2mM GlutaMAX-1). NKTs were expanded for 10 to 12 days and then restimulated with B-8–2 cells (irradiated with 100 Gy). Twenty four-well, non-tissue culture plates were coated with retronectin (Takara Bio) overnight. On day 2 after restimulation, the retronectin-coated plates were washed, inoculated with 1 ml of retroviral supernatant containing anti-CD19 CAR, and spun for 60 minutes at 4,600 g. Viral supernatant was then removed, and stimulated NKTs were added to the wells in complete media and 200 U/ml recombinant IL-2, with or without 10 ng/ml recombinant IL-21. Cells were removed from the plate after 48 hours, washed, resuspended at 106 cells/ml in complete RPMI with IL-2 or IL-2/IL-21 combination, and plated for continued expansion. NKT number was determined by trypan blue (Life Technologies) counting. When indicated, NKTs were labeled with CD62L−PE mAb (GREG-56; BD Biosciences) and anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) followed by magnetic sorting into CD62L+ and CD62L− subsets according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The phenotype of the sorted cells was determined by FACS.

Retro- and lentiviral constructs and retrovirus production

The anti-CD19 CAR construct was made as previously described (14, 23). The construct consists of a single-chain variable fragment from the CD19-specific antibody FMC-63 connected via a short spacer derived from the IgG1 hinge region to the transmembrane domain derived from CD8α, followed by the signaling endodomain of 4–1BB fused with the CD3ζ signaling chain. Retroviral supernatants were produced by transfecting 293T cells with a combination of anti-CD19 CAR-containing plasmid, RDF plasmid encoding the RD114 envelope protein, and PeqPam3 plasmid encoding the MoMLV gag-pol fusion as previously described (14, 23). The lentiviral construct encoding BIM variant 9 (24), envelope plasmid pMD2.G, and packaging plasmid delta 8.2 were generous gifts from Dr. Kenneth Scott and Dr. Yiu-Huen Tsang, Baylor College of Medicine (BCM), and the control lentiviral plasmid encoding non-targeting shRNA was obtained from Origene. Lentiviral supernatants were generated from 293T cells transfected with relevant lentiviral construct(s), pMD2.G, and delta 8.2.

Proliferation and apoptosis assays

NKTs were labeled with CellTrace Violet (CTV; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and stimulated with αGalCer-pulsed B-8–2 cells. Cell proliferation was examined on day 6 by measuring CTV dilution using flow cytometry. Early and late apoptosis were measured on day 3 post-NKT stimulation by staining for annexin-V and 7-AAD (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), respectively, followed by flow cytometry.

Multiplex cytokine quantification assay

CD19-CAR-NKTs were stimulated for 24 hours by Daudi lymphoma cells at a 1:1 ratio. Supernatants were collected and analyzed using the MILLIPLEX MAP Human Cytokine/Chemokine Immunoassay panel (Millipore) for Luminex® analysis according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Flow cytometry

NKT-cell phenotype was assessed using monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for CD3 (UCHT1), Vα24-Jα18 (6B11), CD4 (RPA-T4), granzyme B (GB11), CD62L (DREG-56; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), Vβ11 (C21; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA), and IL-21R (17A12; BioLegend, San Diego, CA and BD Biosciences). CD19-CAR expression by transduced NKTs was detected using anti-Id mAb (clone 136.20.1) (25), a gift from Dr. B. Jena (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX). Intracellular staining was performed using a fixation/permeabilization solution kit (BD Biosciences) with mAbs for Bcl2 (N46–467; BD Biosciences) and BIM (Y36; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) followed by staining with a secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG-AF488 mAb (Abcam). Phosflow staining was performed using Cytofix buffer (BD Biosciences) and Perm buffer III (BD Biosciences) with mAb for Stat3 (pY705; Clone 4; BD Biosciences). Detection of Stat3 phosphorylation was performed after 15 minutes of treatment with IL-21. Fluorochrome- and isotype-matching antibodies suggested by BD Biosciences or R&D Systems were used as negative controls. Analysis was performed on an LSR-II 5-laser flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using BD FACSDiva software version 6.0 and FlowJo 10.1 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity of parental and CD19-CAR-NKTs against Ramos and Raji cells, respectively, was evaluated using a 4-hour luciferase assay as previously described (13).

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was collected using the Direct-zol™ RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Gene expression analysis was performed using the Immunology Panel version 2 (NanoString, Seattle, WA) with the nCounter Analysis System by the BCM Genomic and RNA Profiling Core. Data were analyzed using nSolver 3.0 software (NanoString). Differences in gene expression levels between CD62L+ and CD62L− subsets in the two culture conditions were evaluated using the paired moderated t-statistic of the Linear Models for Microarray Data (Limma) analysis package (26).

In vivo experiments

NSG mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and maintained at the BCM animal care facility. Mice were injected intravenously (IV) with 2 × 105 luciferase-transduced Daudi lymphoma cells to initiate tumor growth. On day 3, mice were injected IV with 4 × 106–8 × 106 CD19-CAR-NKTs followed by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of IL-2 (1,000 U/mouse) only or a combination of IL-2 (1,000 U/mouse) and IL-21 (50 ng/mouse) every other day for two weeks. Tumor growth was assessed once per week by bioluminescent imaging (Small Animal Imaging core facility, Texas Children’s Hospital).

Statistics

We used the Shapiro-Wilk test to assess normality of continuous variables. Normality was rejected when the P value was less than 0.05. For non-normally distributed data, we used the Mann-Whitney U test to evaluate differences in continuous variables between two groups. To evaluate differences in continuous variables, we used two-sided paired Student’s t-tests to compare two groups, one-way ANOVA with post-test Bonferroni correction to compare more than two groups, and two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc test to compare in a two-by-two setting. Survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test to compare two groups. Statistics were computed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences were considered significant when the P value was less than 0.05.

Results

Combined IL-2/IL-21 treatment promotes NKT-cell expansion and increases CD62L+ frequency

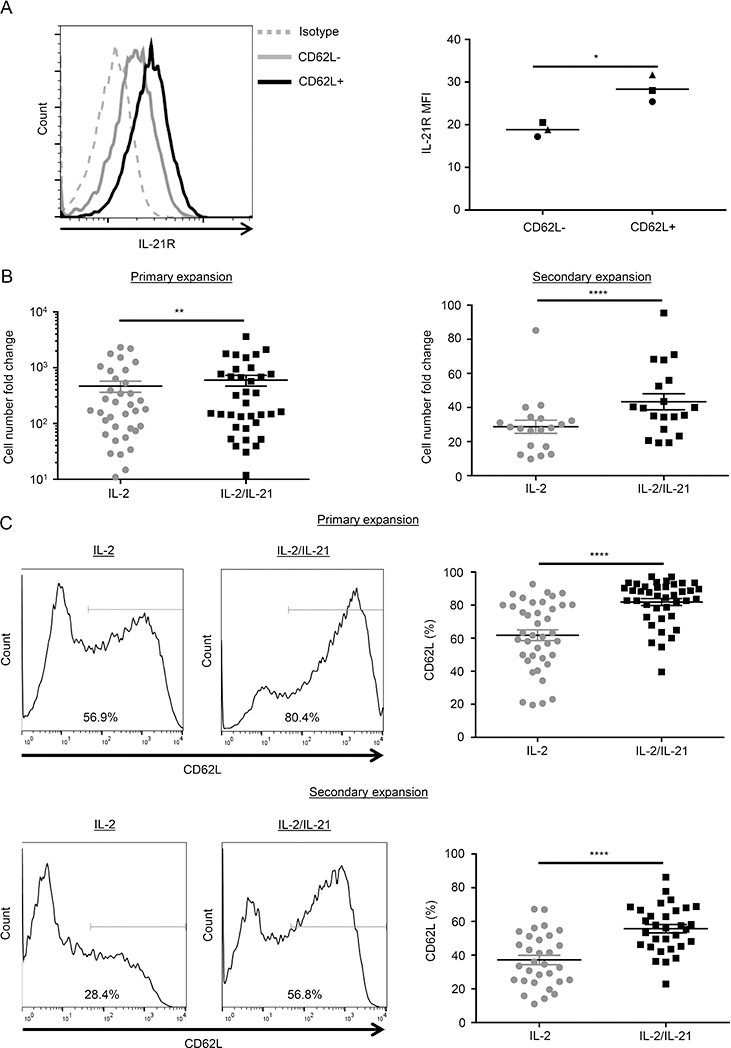

We recently demonstrated that ex vivo-expanded CD62L+ NKTs express significantly higher levels of IL-21R and IL-7R mRNA compared with CD62L− NKTs (14). We confirmed elevated cell-surface expression of both IL-7R (14) and IL-21R in CD62L+ versus CD62L− NKTs (Fig. 1A), suggesting that IL-7 and/or IL-21 signaling may preferentially support maintenance of the CD62L+ NKT subset. To test this hypothesis, we isolated and expanded human peripheral blood NKTs by stimulating with αGalCer-pulsed CD1d+ B-8–2 antigen-presenting cells (14) and supplementing the medium with various combinations of IL-2, IL-21, and IL-7. In contrast to IL-2, IL-7 or IL-21 alone induced little to no NKT-cell expansion. However, combination of IL-21 and/or IL-7 with IL-2 significantly increased NKT numbers compared with the IL-2 only condition (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Fig. 1A). While both IL-2/IL-7 and IL-2/IL-21 cytokine combinations boosted NKT numbers, only IL-2/IL-21 consistently increased the frequency of CD62L+ NKTs compared with IL-2 alone (Fig. 1C and Supplemental Fig. 1B), leading us to shift focus solely to IL-21. We also observed accumulation of CD4+ NKTs in cells cultured with IL-2/IL-21 versus IL-2 alone (Supplemental Fig. 1C), but CD62L expression was elevated in both CD4+ and CD4− cells grown with the cytokine combination (Supplemental Fig. 1D). This suggests that the increased frequency of CD62L+ cells in the IL-2/IL-21 growth condition occurs independently of the preferential expansion of CD4+ NKTs. Overall, these results demonstrate that both IL-2/IL-7 and IL-2/IL-21 combinations increase the number of NKTs generated in response to antigenic stimulation compared with IL-2 alone, but only the latter increases prevalence of the CD62L+ subset.

Figure 1. Combined treatment with IL-2 and IL-21 produces more NKTs and increases the frequency of CD62L+ NKTs compared with IL-2 alone.

(A) IL-21R expression of ex vivo expanded primary NKTs was examined using flow cytometry at day 4 after antigenic stimulation with αGalCer-pulsed irradiated B-8–2 antigen-presenting cells. NKTs were gated into CD62L+ and CD62L− populations, and their respective IL-21R expression was measured. A representative histogram from one of three donors (left) and mean of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for all donors (n = 3, right) were shown. Each symbol denotes an individual donor. *P < 0.05, paired Student’s t test. (B) Following primary or secondary stimulation as described in (A), NKTs were cultured with the indicated cytokines for 12 or 10 days, respectively. NKT-cell number was determined using the trypan blue exclusion assay. Cell count fold-change compared with day 0 is shown as the mean ± SEM for all donors following primary expansion (n = 36, left) and secondary expansion (n = 19, right). (C) NKTs were expanded as described in (B). CD62L expression of NKTs was examined using flow cytometry on days 12 and 10 after primary and secondary stimulation, respectively. Representative histograms (left) or the mean ± SEM of percentage of CD62L+ NKTs for all donors (right) following primary expansion (n = 40, top panel) and secondary expansion (n = 31, bottom panel) are shown. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test.

CD62L+ NKTs preferentially upregulate IL-21R following antigenic stimulation and are selectively protected from AICD by IL-21

To determine whether the differential IL-21R expression observed in CD62L+ versus CD62L− subsets is present in primary, unmanipulated NKTs or induced by antigenic stimulation, we performed a multi-parameter flow cytometry analysis on freshly isolated peripheral blood NKTs. We found that IL-21R was expressed at comparable levels in CD62L+ and CD62L− subsets of freshly isolated NKTs (P = 0.71)(Fig. 2A), and that NKTs upregulated IL-21R expression within 24 h of αGalCer stimulation, reaching maximum expression by 72 h (Fig. 2B). CD62L+ NKTs achieved significantly higher levels of IL-21R expression and sustained peak-level expression longer than CD62L− NKTs (P < 0.05). In line with this, CD62L+ NKTs demonstrated higher Stat3 phosphorylation levels than CD62L− NKTs in response to a range of IL-21 concentrations (Supplemental Fig. 1E). These data indicate that antigenic stimulation preferentially sensitizes CD62L+ NKTs to IL-21.

Figure 2. CD62L+ NKTs upregulate IL-21R following antigenic stimulation and are selectively protected by IL-21.

(A) IL-21R expression of CD62L+ and CD62L− NKTs was analyzed within populations of freshly isolated PBMCs using flow cytometry. 7-AAD+ dead cells were excluded, and the remainder were gated for CD3+/Vβ11+/Vα24-Jα18+ NKTs. Representative flow cytometry plots are from one of four healthy donors. Mean of MFI for all donors was shown (n = 4). Each symbol represents an individual donor. ns: not significant, paired Student’s t-test. (B) NKTs were stimulated with αGalCer-pulsed irradiated B-8–2 cells and cultured in medium supplemented with IL-2. IL-21R expression was analyzed in CD62L+ and CD62L− NKTs using flow cytometry at the indicated time intervals following stimulation. Fold MFI increase was calculated by dividing the MFI value at each time point by the MFI value of the isotype control. Shown are the mean ± SEM from three donors. ns: not significant, *P < 0.05, paired Student’s t-test. (C) CTV-labeled NKTs were magnetically sorted into CD62L+ and CD62L− subsets and stimulated with αGalCer-pulsed B-8–2 cells cultured in medium with IL-2 or IL-2/IL-21. Cell proliferation was assessed on day 6 after stimulation. Shown are representative results from one of four donors (left) and mean of CTV MFI for all donors (n = 4 donors, right). Each symbol represents an individual donor. ns: not significant, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc test. (D) NKTs were sorted and stimulated as described in (C). Annexin-V and 7-AAD staining was performed on day 3 after stimulation. Shown are representative results from one of eight donors tested (left) and mean of percentage of annexin-V+/7-AAD-NKTs for all donors (n = 8 donors, right). Each symbol represents an individual donor. ns: not significant, *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc test.

To determine how IL-21 increases the frequency of CD62L+ NKTs, we sorted NKTs into CD62L+ and CD62L− subsets, stimulated them with αGalCer, and measured their proliferation and apoptosis rates after culture with IL-2 or IL-2/IL-21. Co-treatment with IL-2 and IL-21 did not affect NKT-cell proliferation in either subset six days after stimulation (Fig. 2C). By contrast, in the CD62L+ subset, IL-2/IL-21 treatment reduced the frequency of early apoptotic cells (annexin-V+/7-AAD-) at three days post-stimulation compared with IL-2 treatment alone (Fig. 2D). These findings show that IL-21 preserves CD62L+ NKTs by selectively reducing the occurrence of AICD in this subset.

IL-2/IL-21 downregulates pro-apoptotic factor BIM in CD62L+ NKTs

To understand how IL-21 reduces AICD in CD62L+ NKTs, we evaluated the mRNA expression levels of immune-related genes in stimulated CD62L+ and CD62L− NKTs grown with IL-2/IL-21 or IL-2 only for 24 h. We observed that culturing with IL-2/IL-21 versus IL-2 resulted in significant downregulation of multiple genes in both NKT subsets.

Using stringent Nanostring gene expression analysis parameters (FDR < 0.01), we found that BCL2L11 was downregulated in the CD62L+ versus CD62L− subset specifically in the IL-2/IL-21 and not the IL-2 only condition (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 2A). BCL2L11 encodes the pro-apoptotic protein BIM, a member of the BCL2 family that acts in conjunction with other BCL2 proteins to initiate the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (27). Intracellular flow cytometry confirmed that BIM expression was markedly downregulated in CD62L+ but not CD62L− NKTs cultured with IL-2/IL-21 versus those cultured with IL-2 alone (Fig. 3B). Because intrinsic apoptosis initiation depends on the ratio of pro- to anti-apoptotic BCL2 proteins (28), we measured expression of BCL2, the primary anti-apoptotic regulator, in NKTs under the same experimental conditions as above. Fig. 3C shows that BCL2 expression levels were not affected by IL-21. To determine whether BIM downregulation is required for IL-21-mediated reduction of AICD in the CD62L+ subset, we transduced CD62L+ NKTs with lentiviral vectors expressing either BIM splice variant 9 (24) or a control construct (Supplemental Fig. 2B). As expected, NKTs transduced with the control construct showed decreased levels of BIM expression in the IL-2/IL-21 condition versus IL-2 alone. Overexpression of BIM variant 9 in IL-2/IL-21-cultured NKTs restored BIM expression to a level similar to that observed in control NKTs stimulated with IL-2 alone. While control CD62L+ NKTs demonstrated significantly lower rates of apoptosis in the IL-2/IL-21 versus IL-2 condition, overexpression of BIM completely abrogated the protective effect of IL-21 (Supplemental Fig. 2C). In contrast, neither IL-21 treatment nor BIM overexpression affected the high rate of apoptosis observed in CD62L− NKTs (Supplemental Fig. 2D). Thus, IL-21 selectively inhibits the expression of pro-apoptotic factor BIM in CD62L+ NKTs, without affecting expression of anti-apoptotic BCL2, to mediate protection of CD62L+ subset from AICD.

Figure 3. Alleviation of AICD by IL-2/IL-21 in CD62L+ NKTs is associated with selective downregulation of BIM.

(A) NKTs were magnetically sorted into CD62L+ (left) and CD62L− (right) subsets; stimulated with plate-coated agonistic anti-CD3, anti-CD28, and anti-4–1BB mAbs; and cultured with IL-2 or IL-2/IL-21. mRNA was isolated after 24 h, and gene expression analysis was performed using the Human Immunology Panel version 2 and the nCounter Analysis System (NanoString). Heat maps show log2-fold gene expression changes (FDR values < 0.01) in CD62L+ versus CD62L− subsets. Data were generated from the NKTs of six donors (24 paired samples). (B, C) NKTs were stimulated with plate-coated agonistic anti-CD3, anti-CD28, and anti-4–1BB mAbs and cultured with IL-2 or IL-2/IL-21 for 24 h. BIM (B) and BCL2 (C) expression in CD62L+/− gated subsets was measured using intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Shown are representative results from one of three donors (left) and mean of MFI for all donors (n = 3 donors, right). Each symbol represents an individual donor. ns: not significant, *P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc test.

IL-21 enhances TCR- and CAR-mediated NKT-cell cytotoxicity by upregulating granzyme B expression

To examine the effect of IL-21 treatment on TCR-dependent NKT-cell cytotoxicity, we co-cultured NKTs with CD1d+ Ramos lymphoma target cells pulsed with αGalCer. Fig. 4A shows that addition of IL-21 to the co-culture significantly enhanced the CD1d-restricted cytotoxicity of NKTs against lymphoma cells at all tested effector-to-target ratios. Next, we transduced NKTs with a previously described CD19-specific CAR containing a 4–1BB costimulatory endodomain (14) and evaluated their cytotoxicity against CD19+CD1d-Raji lymphoma cells. CAR-NKTs killed Raji cells more effectively at effector-to-target ratios less than 10-to-1 when they were expanded with IL-2/IL-21 versus IL-2 alone (Fig. 4B). As short-term in vitro cytotoxicity of human NKTs is primarily mediated by cytotoxic granule exocytosis (29), we performed intracellular staining for two major components of this pathway: perforin and granzyme B. Perforin was highly expressed in both subsets independent of co-treatment with IL-21 (data not shown). When cultured with IL-2 alone, CD62L− cells expressed a higher level of granzyme B than CD62L+ cells (P < 0.01, Fig. 4C), while IL-2/IL-21 treatment significantly increased granzyme B expression to similarly high levels in both CD62L+ and CD62L− NKTs. In line with this, IL-21 preferentially increased the cytotoxicity of CD62L+ NKTs, which are typically less cytotoxic than CD62L− cells when cultured with IL-2 alone (Fig. 4D). Therefore, IL-21-mediated upregulation of granzyme B expression in NKTs maximizes their cytotoxic potential.

Figure 4. IL-21 enhances TCR- and CAR-mediated NKT-cell cytotoxicity via upregulation of granzyme B.

(A) Luciferase-transduced CD1d+ Ramos cells were co-cultured with IL-2- or IL-2/IL-21-expanded NKTs. Cytotoxicity was calculated after 4 h by measuring luminescence intensity with a plate reader. Ramos cells not pulsed with αGalCer were used as a control. Shown is data pooled from two independent experiments with three donors each, mean ± SEM (n = 6). ns: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, paired Student’s t-test. (B) CD19+ Raji cells were co-cultured with CD19-CAR-NKTs and CD19-CAR-dependent cytotoxicity was measured as described in (A). Non-transduced (NT) NKTs were used as a control. Shown is data pooled from two independent experiments with three donors each, mean ± SEM (n = 6). ns: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, paired Student’s t-test. (C) Granzyme B expression in CD62L+ and CD62L− subsets supplemented with IL-2 or IL-2/IL-21 was examined at days 10–12 after primary stimulation. Shown are representative results from one of seven donors (left) and mean of MFI for all donors (n = 7, right). Each symbol represents an individual donor. ns: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. (D) NKTs were magnetically sorted into CD62L+ and CD62L− subsets, stimulated with irradiated αGalCer-pulsed B-8–2 cells, and treated with IL-2 or IL-2/IL-21. At day 3 after stimulation, luciferase-transduced CD1d+ Ramos cells were co-cultured with IL-2- or IL-2/IL-21-expanded NKTs. Cytotoxicity was calculated after 4 h by measuring luminescence intensity with a plate reader. NT NKTs were used as a control. Shown are the results of the two donors tested.

IL-21 skews NKT-cell cytokine secretion toward a TH1-like profile

We previously demonstrated that the CD62L+ subset is the main source of cytokines produced by NKTs (14). Here, we evaluated the impact of IL-2/IL-21 on CD19-CAR-NKT cytokine production following co-culture with CD19+ Daudi cells. Luminex analysis of co-culture supernatants collected after 24 h revealed that IL-2/IL-21 treatment increased GM-CSF and IFN-γ production in NKTs derived from three different donors (Fig. 5A). Co-cultured NKTs from two of three donors showed increased IL-4 production, whereas NKTs from one donor showed decreased IL-4 production. Despite this inter-individual variability, IL-2/IL-21 treatment consistently increased the IFN-γ-to-IL-4 ratio, a measure of TH1 versus TH2 polarization compared with IL-2 alone. Following CAR stimulation, NKTs produced high levels of another TH1 cytokine, TNFα, which increased significantly in the presence of IL-21 compared with IL-2 alone in two of three donors (Supplemental Fig. 3). IL-2/IL-21 treatment also enhanced IL-10 production in all three donors, although absolute concentrations of this cytokine were many-fold lower than those of the TH1 cytokines. IL-17A was minimally detectable (two donors) or undetectable (one donor) regardless of culture with IL-21. Previous work has shown that murine NKTs produce endogenous IL-21 following in vitro stimulation via CD3 and CD28 (30). Consistent with this observation, we found that antigenic stimulation of human NKTs with αGalCer induced a modest level of IL-21 production that peaked within 24 h and became undetectable by 72 h (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the CD62L+ subset was overwhelmingly the primary source of IL-21 production in three donors tested (Fig. 5C). In all, these findings indicate that IL-21 polarizes NKT cytokine production toward a TH1-like profile, and that transient production of endogenous IL-21 by antigen-stimulated NKTs may further support NKT-cell functionality through autocrine signaling.

Figure 5. IL-21 skews NKT-cell cytokine secretion toward a TH1-like profile.

(A) IL-2- or IL-2/IL-21-expanded CD19-CAR-NKTs were stimulated with CD19+ Daudi lymphoma cells, and supernatants were collected at 24 h. Concentrations of GM-CSF, IFN-γ, and IL-4 in supernatants were measured using a Luminex assay. Data are from two independent experiments with three donors in total, and the IFN-γ-to-IL-4 ratio was calculated. Mean ± SD of three donors are shown. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, unpaired Student’s t-test. (B) NKTs were stimulated in vitro with irradiated α-GalCer-pulsed B-8–2 cells and IL-2. Culture supernatants were collected 24, 48, and 72 h after stimulation and IL-21 levels were assessed by ELISA. Shown are the mean IL-21 concentration (pg/ml) ± SD of three donors. (C) NKTs were magnetically sorted into CD62L+ and CD62L− subsets and stimulated with α-GalCer-pulsed B-8–2 cells. Culture supernatants were collected 24 h after stimulation and IL-21 levels were assessed by ELISA. Shown are mean IL-21 concentrations ± SD for each of the three donors. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired Student’s t-test.

IL-2/IL-21-expanded CAR-NKTs have superior anti-tumor activity in vivo

Next, we examined the effect of IL-21 on the in vivo therapeutic potential of CAR-redirected NKTs in a murine model of lymphoma. We IV injected NSG mice with luciferase-transduced CD19+ Daudi lymphoma cells followed four days later by adoptive transfer of CD19-CAR-NKTs expanded with IL-2 or IL-2/IL-21. To evaluate the potential benefit of in vivo IL-21 supplementation, mice from the two groups were further subdivided to receive IP injections of either IL-2 or IL-2/IL-21. IL-2-expanded CAR-NKTs had marked therapeutic activity and doubled mouse survival compared with the untreated control group; however, there were few long-term survivors with undetectable disease as measured at 13 weeks post-tumor cell injection (P < 0.0001, Fig. 6). IL-2/IL-21-expanded CAR-NKTs instead mediated striking long-term disease-free survival in treated mice, significantly improving their survival probability compared to those treated with IL-2-expanded cells (P < 0.01). In vivo supplementation with IL-2/IL-21 versus IL-2 did not significantly improve the survival probability of mice receiving either IL-2- or IL-2/IL-21-expanded CAR-NKTs (P = 0.65 and P = 0.32, respectively). Similar results were observed in an independent repeat of this experiment (Supplemental Fig. 4). Notably, CAR-NKT treated mice displayed no clinical or postmortem pathological signs of xeno-GVHD or other toxic side effects (data not shown). Overall, our results indicate that addition of IL-21 to the growth culture of NKTs strongly enhances their therapeutic potential and should be considered for inclusion in CAR-NKT-cell manufacturing processes for lymphoma immunotherapy.

Figure 6. IL-2/IL-21-expanded NKTs have superior in vivo anti-tumor activity.

(A) NKTs expanded with IL-2 (IL-2 NKTs) or the combination of IL-2/IL-21 (IL-2/IL-21 NKTs) were transduced with a CD19-CAR. Mice were separated into five groups (n=10 mice/group) before receiving an IV injection of 2 × 105 luciferase-transduced Daudi cells on day 0. On day 3, mice received an IV injection of the indicated NKT preparations (107 cells per mouse) and an IP injection of IL-2 (IP IL-2) or IL-2/IL-21 (IP IL-2/IL-21). Tumor growth was monitored using bioluminescence imaging once per week. (B) A survival plot was generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Shown data from one of two independent experiments with similar results. Differences in survival probability were compared using the log-rank test. ** P < 0.01.

Discussion

αGalCer-specific NKTs are an attractive cellular platform for CAR-redirected immunotherapy as an alternative or partner approach to polyclonal T cells. We previously demonstrated that human NKTs can be engineered to express tumor-specific CARs and subsequently expanded ex vivo on a clinical scale (13). We also discovered that the CD62L+ subset is required for NKT- and CAR-NKT-cell numeric expansion, in vivo persistence, and therapeutic activity (14). However, the requirements for maintaining, functionally preserving, or further enhancing the therapeutic potential of CD62L+ NKTs remain largely unknown, limiting the development of NKT-cell-based adoptive immunotherapy. In this study, we demonstrate that following antigenic stimulation, CD62L+ NKTs preferentially upregulate IL-21R and are selectively protected from AICD by IL-21 via downregulation of BIM expression. While IL-21 alone was unable to support the proliferation of αGalCer-stimulated NKTs, the combination of IL-2 and IL-21 increased the yield of total expanded NKTs or CD19-CAR-NKTs with a significant increase in frequency of CD62L+ NKTs. Importantly, IL-21 increased granzyme B expression in NKTs, making NKT- and CAR-NKT-cell preparations significantly more cytotoxic against lymphoma cells in a CD1d- and CD19-dependent manner, respectively. We also observed that IL-21 increased the TH1-like polarization of the NKT-cell cytokine profile secreted in response to specific stimulation, further boosting anti-tumor effector functionality. Finally, IL-2/IL-21-expanded CAR-NKTs significantly increased the rate of tumor-free long-term survival of lymphoma-bearing NSG mice.

While IL-21R expression has been reported previously in both human and murine NKTs (22, 30), here we demonstrate for the first time that IL-21R is expressed at a higher level in the CD62L+ subset of human ex vivo-expanded NKTs compared with the CD62L− subset. This observation has crucial implications for the development of NKT-cell-based cancer immunotherapy, because the CD62L+ subset promotes in vivo persistence and anti-tumor activity of adoptively transferred NKTs or CAR-NKTs (14). Interestingly, we found uniform IL-21R expression levels across both CD62L+ and CD62L− subsets of freshly isolated peripheral blood NKTs, but CD62L+ NKTs preferentially upregulated IL-21R following antigenic stimulation. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that PLZF, a transcriptional master regulator of NKT-cell differentiation (31–33), represses gene expression of both CD62L and IL-21R. TCR stimulation could interfere with the PLZF-mediated repression, resulting in a coordinated upregulation of CD62L and IL-21R in NKTs. However, repeated TCR stimulation has been shown to induce terminal differentiation in T and NKT cells (34), and, consistent with this observation, we found that IL-21R and CD62L expression were downregulated in NKTs after repeated αGalCer stimulation. Importantly, addition of IL-21 to the NKT culture medium helped maintain the CD62L+ subset, even after repeated stimulation, allowing the expansion of central-memory-like cells with high therapeutic potential.

We found that IL-21 supported the accumulation of CD62L+ NKTs without affecting their proliferation rate, but instead by inhibiting AICD in response to αGalCer/IL-2 stimulation. This mode of action in human NKTs differs from that reported by Coquet et al. in a murine system, where IL-21 promoted proliferation of IL-2-stimulated thymic or αGalCer-stimulated splenic NKTs (30). These differences could be species-specific and/or the result of different anatomical sites from which NKT cells originate. Consistent with our observations, IL-21 has been found to promote CD62L expression and central-memory-like differentiation in both human and mouse naïve CD8 T cells, and to counteract terminal differentiation/exhaustion of these cells following antigenic stimulation with IL-2 or IL-15 (35–37). Further, priming of naïve tumor-specific T cells with IL-21 has been shown to potently enhance their anti-tumor activity following adoptive transfer into mice (37), and cells produced using this technique have shown promising results in cancer immunotherapy clinical trials (38, 39). However, IL-21 has also been reported to promote terminal differentiation of B cells and antigen-experienced T cells (40–43). These findings suggest that IL-21 acts on lymphocyte subsets in a context-dependent manner that can be influenced by varying states of cell differentiation or activation as highlighted in recent reviews (20, 44).

Mechanistically, we present the original finding that IL-21 inhibits AICD selectively in CD62L+ NKTs by downregulating pro-apoptotic BIM expression without affecting anti-apoptotic BCL2, ultimately shifting the balance of BCL2 family proteins in favor of cell survival (45, 46). Interestingly, IL-21 can induce BIM-dependent apoptosis in LPS-activated B cells (47) but also promotes survival of vaccinia-virus-specific CD8 T cells by upregulating BCL2 and BCL-XL expression (48). These disparate observations reinforce the idea that IL-21 signaling has cell-type-specific effects. While our results indicate that IL-21 maintains CD62L+ NKTs by preventing AICD, we cannot exclude the possibility that IL-21 also inhibits NKT terminal differentiation given that this occurs in antigen-stimulated naïve T cells through repression of Eomes (37). However, IL-21-mediated suppression of T cell differentiation in that instance was associated with granzyme B downregulation and decreased cytolytic function, while we found the opposite effect in both cases for NKTs. This suggests that IL-21 could benefit the anti-tumor therapeutic potential of NKTs more than T cells.

With respect to cytokine production, IL-21 skewed NKTs toward a TH1-like profile as evidenced by increased production of IFN-γ, GM-CSF, and TNFα, and an increased IFN-γ-to-IL-4 ratio. NKTs are known to produce large amounts of numerous cytokines, which individually may exert opposing effects on tumor immunity. Ultimately, the balance of these cytokines may determine the outcome of NKT-cell activation in vivo. In mice, IL-21 has been shown instead to promote a TH2-like cytokine secretion profile in NKT thymocytes and to increase IL-4 and IFNγ production in liver NKTs (30). In a recent phase IIA clinical trial of recombinant IL-21 in melanoma patients, IFN-γ and TNFα levels produced by peripheral blood NKTs decreased over the course of five days while IL-4 levels increased (49). These seemingly contradictory observations may be explained by the fact that NKT IFN-γ production is impaired in cancer patients, particularly those with advanced disease, but can be restored after ex vivo stimulation and expansion (50–52). Therefore, culture conditions play an important role in modulating the therapeutic potential of NKTs, and our results indicate that IL-21-induced TH1-like cytokine polarization enhances NKT anti-tumor effector function.

Importantly, we observed a striking enhancement of IL-2/IL-21-expanded CD19-CAR-NKT therapeutic efficacy compared with IL-2-expanded CD19-CAR-NKTs in an aggressive model of B-cell lymphoma in NSG mice. Indeed, supplementing the culture with IL-21 promoted the same level of CAR-NKT anti-lymphoma activity as we previously observed after sorting the cells into a 100% pure CD62L+ population (14). By contrast, IP administration of IL-21 following CAR-NKT-cell transfer had little to no effect on treatment outcome. There are limitations to the use of a xenogenic model system in immune deficient mice, specifically that we cannot evaluate the impact of CAR-NKT-cell and/or IL-21 therapy on the host immune system.

As both NKTs and IL-21 can potently activate innate and adaptive tumor immune responses and have been proven safe in clinical trials (52, 53), there is sound scientific basis for combining NKT-cell therapy with IL-21 administration in future clinical studies. Overall, our results support the inclusion of IL-21 in NKT-cell ex vivo-expansion protocols for lymphoma adoptive immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Kenneth Scott and Dr. Yiu-Huen Tsang (BCM) for the generous gift of BIM variant 9-IRES-GFP lentiviral plasmid. The authors are also grateful for the excellent technical assistance provided by the staff at the BCM Genomic and RNA Profiling Core, Flow Cytometry Core Laboratory of the Texas Children’s Cancer and Hematology Center, and Small Animal Imaging core facility at Texas Children’s Hospital.

Financial Support

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 CA116548, P50 CA126752, and S10 OD020066 to L.S.M.), and Cell Medica, Ltd (to L.S.M.).

Financial support: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA116548 and P50 CA126752), the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (DP150083), Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer, Cookies for Kid’s Cancer Foundation, and an industry-sponsored research agreement with Cell Medica, Ltd.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

G.T., A.N.C., and L.S.M are co-inventors on pending patent applications that relate to the use of NKTs in cancer immunotherapy and have been licensed by BCM to Cell Medica, Ltd. for commercial development. Cell Medica, Ltd. provided research support for this project (to L.S.M.) via a sponsored research agreement with BCM.

H.N., S.B.R., B.L., J.J., E.S. and E.J.D.P. declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Lichtman EI, and Dotti G. 2017. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cells for B-cell malignancies. Transl Res 187: 59–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brudno JN, and Kochenderfer JN. 2018. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies for lymphoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15: 31–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh N, Perazzelli J, Grupp SA, and Barrett DM. 2016. Early memory phenotypes drive T cell proliferation in patients with pediatric malignancies. Science translational medicine 8: 320ra323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz CR, Micklethwaite KP, Savoldo B, Ramos CA, Lam S, Ku S, Diouf O, Liu E, Barrett AJ, Ito S, Shpall EJ, Krance RA, Kamble RT, Carrum G, Hosing CM, Gee AP, Mei Z, Grilley BJ, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Brenner MK, Bollard CM, and Dotti G. 2013. Infusion of donor-derived CD19-redirected virus-specific T cells for B-cell malignancies relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant: a phase 1 study. Blood 122: 2965–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu E, Tong Y, Dotti G, Shaim H, Savoldo B, Mukherjee M, Orange J, Wan X, Lu X, Reynolds A, Gagea M, Banerjee P, Cai R, Bdaiwi MH, Basar R, Muftuoglu M, Li L, Marin D, Wierda W, Keating M, Champlin R, Shpall E, and Rezvani K. 2017. Cord blood NK cells engineered to express IL-15 and a CD19-targeted CAR show long-term persistence and potent antitumor activity. Leukemia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du SH, Li Z, Chen C, Tan WK, Chi Z, Kwang TW, Xu XH, and Wang S. 2016. Co-Expansion of Cytokine-Induced Killer Cells and Vgamma9Vdelta2 T Cells for CAR T-Cell Therapy. PloS one 11: e0161820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metelitsa LS 2011. Anti-tumor potential of type-I NKT cells against CD1d-positive and CD1d-negative tumors in humans. Clin.Immunol. 140: 119–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossjohn J, Pellicci DG, Patel O, Gapin L, and Godfrey DI. 2012. Recognition of CD1d-restricted antigens by natural killer T cells. Nature reviews. Immunology 12: 845–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song L, Asgharzadeh S, Salo J, Engell K, Wu HW, Sposto R, Ara T, Silverman AM, DeClerck YA, Seeger RC, and Metelitsa LS. 2009. Valpha24-invariant NKT cells mediate antitumor activity via killing of tumor-associated macrophages. J.Clin.Invest 119: 1524–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchesi F, Cirillo M, Bianchi A, Gately M, Olimpieri OM, Cerchiara E, Renzi D, Micera A, Balzamino BO, Bonini S, Onetti MA, and Avvisati G. 2014. High density of CD68+/CD163+ tumour-associated macrophages (M2-TAM) at diagnosis is significantly correlated to unfavorable prognostic factors and to poor clinical outcomes in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol.Oncol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pillai AB, George TI, Dutt S, Teo P, and Strober S. 2007. Host NKT cells can prevent graft-versus-host disease and permit graft antitumor activity after bone marrow transplantation. J.Immunol. 178: 6242–6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de LC, Rinaldi A, Montagna D, Azzimonti L, Bernardo ME, Sangalli LM, Paganoni AM, Maccario R, Di Cesare-Merlone A, Zecca M, Locatelli F, Dellabona P, and Casorati G. 2011. Invariant NKT cell reconstitution in pediatric leukemia patients given HLA-haploidentical stem cell transplantation defines distinct CD4+ and CD4− subset dynamics and correlates with remission state. J.Immunol. 186: 4490–4499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heczey A, Liu D, Tian G, Courtney AN, Wei J, Marinova E, Gao X, Guo L, Yvon E, Hicks J, Liu H, Dotti G, and Metelitsa LS. 2014. Invariant NKT cells with chimeric antigen receptor provide a novel platform for safe and effective cancer immunotherapy. Blood 124: 2824–2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian G, Courtney AN, Jena B, Heczey A, Liu D, Marinova E, Guo L, Xu X, Torikai H, Mo Q, Dotti G, Cooper LJ, and Metelitsa LS. 2016. CD62L+ NKT cells have prolonged persistence and antitumor activity in vivo. The Journal of clinical investigation 126: 2341–2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Palmer DC, Wrzesinski C, Kerstann K, Yu Z, Finkelstein SE, Theoret MR, Rosenberg SA, and Restifo NP. 2005. Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the in vivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J.Clin.Invest 115: 1616–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Torabi-Parizi P, Kerstann K, Cardones AR, Finkelstein SE, Palmer DC, Antony PA, Hwang ST, Rosenberg SA, Waldmann TA, and Restifo NP. 2005. Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A 102: 9571–9576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gapin L 2016. Development of invariant natural killer T cells. Curr Opin Immunol 39: 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Der Vliet HJ, Nishi N, De Gruijl TD, von Blomberg BM, van den Eertwegh AJ, Pinedo HM, Giaccone G, and Scheper RJ. 2000. Human natural killer T cells acquire a memory-activated phenotype before birth. Blood 95: 2440–2442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceredig R, and Rolink AG. 2012. The key role of IL-7 in lymphopoiesis. Semin Immunol 24: 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard WJ, and Wan CK. 2016. IL-21 Signaling in Immunity. F1000Res 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Tani-ichi S, Shimba A, Wagatsuma K, Miyachi H, Kitano S, Imai K, Hara T, and Ikuta K. 2013. Interleukin-7 receptor controls development and maturation of late stages of thymocyte subpopulations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 612–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson RP, Ives ML, Rao G, Lau A, Payne K, Kobayashi M, Arkwright PD, Peake J, Wong M, Adelstein S, Smart JM, French MA, Fulcher DA, Picard C, Bustamante J, Boisson-Dupuis S, Gray P, Stepensky P, Warnatz K, Freeman AF, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J, Holland SM, Casanova JL, Uzel G, Ma CS, Tangye SG, and Deenick EK. 2015. STAT3 is a critical cell-intrinsic regulator of human unconventional T cell numbers and function. The Journal of experimental medicine 212: 855–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vera J, Savoldo B, Vigouroux S, Biagi E, Pule M, Rossig C, Wu J, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Brenner MK, and Dotti G. 2006. T lymphocytes redirected against the kappa light chain of human immunoglobulin efficiently kill mature B lymphocyte-derived malignant cells. Blood 108: 3890–3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du H, Wolf J, Schafer B, Moldoveanu T, Chipuk JE, and Kuwana T. 2011. BH3 domains other than Bim and Bid can directly activate Bax/Bak. The Journal of biological chemistry 286: 491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jena B, Maiti S, Huls H, Singh H, Lee DA, Champlin RE, and Cooper LJ. 2013. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-specific monoclonal antibody to detect CD19-specific T cells in clinical trials. PLoS.One. 8: e57838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smyth GK 2005. Limma: Linear Models for Microarray Data In Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Gentleman RC, J. V; Huber W; Irizarry RA; Dudoit S;, et al. , ed. Springer, New York. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sionov RV, Vlahopoulos SA, and Granot Z. 2015. Regulation of Bim in Health and Disease. Oncotarget 6: 23058–23134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouillet P, and O’Reilly LA. 2009. CD95, BIM and T cell homeostasis. Nature reviews. Immunology 9: 514–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metelitsa LS, Naidenko OV, Kant A, Wu HW, Loza MJ, Perussia B, Kronenberg M, and Seeger RC. 2001. Human NKT cells mediate antitumor cytotoxicity directly by recognizing target cell CD1d with bound ligand or indirectly by producing IL-2 to activate NK cells. J.Immunol. 167: 3114–3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coquet JM, Kyparissoudis K, Pellicci DG, Besra G, Berzins SP, Smyth MJ, and Godfrey DI. 2007. IL-21 is produced by NKT cells and modulates NKT cell activation and cytokine production. J.Immunol. 178: 2827–2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao AP, Constantinides MG, Mathew R, Zuo Z, Chen X, Weirauch MT, and Bendelac A. 2016. Multiple layers of transcriptional regulation by PLZF in NKT-cell development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113: 7602–7607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savage AK, Constantinides MG, Han J, Picard D, Martin E, Li B, Lantz O, and Bendelac A. 2008. The transcription factor PLZF directs the effector program of the NKT cell lineage. Immunity. 29: 391–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovalovsky D, Uche OU, Eladad S, Hobbs RM, Yi W, Alonzo E, Chua K, Eidson M, Kim HJ, Im JS, Pandolfi PP, and Sant’Angelo DB. 2008. The BTB-zinc finger transcriptional regulator PLZF controls the development of invariant natural killer T cell effector functions. Nature immunology 9: 1055–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loza MJ, Metelitsa LS, and Perussia B. 2002. NKT and T cells: coordinate regulation of NK-like phenotype and cytokine production. Eur.J.Immunol. 32: 3453–3462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Bleakley M, and Yee C. 2005. IL-21 influences the frequency, phenotype, and affinity of the antigen-specific CD8 T cell response. J Immunol 175: 2261–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alves NL, Arosa FA, and van Lier RA. 2005. IL-21 sustains CD28 expression on IL-15-activated human naive CD8+ T cells. J Immunol 175: 755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinrichs CS, Spolski R, Paulos CM, Gattinoni L, Kerstann KW, Palmer DC, Klebanoff CA, Rosenberg SA, Leonard WJ, and Restifo NP. 2008. IL-2 and IL-21 confer opposing differentiation programs to CD8+ T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood 111: 5326–5333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapuis AG, Roberts IM, Thompson JA, Margolin KA, Bhatia S, Lee SM, Sloan HL, Lai IP, Farrar EA, Wagener F, Shibuya KC, Cao J, Wolchok JD, Greenberg PD, and Yee C. 2016. T-Cell Therapy Using Interleukin-21-Primed Cytotoxic T-Cell Lymphocytes Combined With Cytotoxic T-Cell Lymphocyte Antigen-4 Blockade Results in Long-Term Cell Persistence and Durable Tumor Regression. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 34: 3787–3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapuis AG, Lee SM, Thompson JA, Roberts IM, Margolin KA, Bhatia S, Sloan HL, Lai I, Wagener F, Shibuya K, Cao J, Wolchok JD, Greenberg PD, and Yee C. 2016. Combined IL-21-primed polyclonal CTL plus CTLA4 blockade controls refractory metastatic melanoma in a patient. The Journal of experimental medicine 213: 1133–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozaki K, Spolski R, Feng CG, Qi CF, Cheng J, Sher A, Morse HC 3rd, Liu C, Schwartzberg PL, and Leonard WJ. 2002. A critical role for IL-21 in regulating immunoglobulin production. Science 298: 1630–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozaki K, Spolski R, Ettinger R, Kim HP, Wang G, Qi CF, Hwu P, Shaffer DJ, Akilesh S, Roopenian DC, Morse HC 3rd, Lipsky PE, and Leonard WJ. 2004. Regulation of B cell differentiation and plasma cell generation by IL-21, a novel inducer of Blimp-1 and Bcl-6. J Immunol 173: 5361–5371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasaian MT, Whitters MJ, Carter LL, Lowe LD, Jussif JM, Deng B, Johnson KA, Witek JS, Senices M, Konz RF, Wurster AL, Donaldson DD, Collins M, Young DA, and Grusby MJ. 2002. IL-21 limits NK cell responses and promotes antigen-specific T cell activation: a mediator of the transition from innate to adaptive immunity. Immunity 16: 559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moretto MM, and Khan IA. 2016. IL-21 Is Important for Induction of KLRG1+ Effector CD8 T Cells during Acute Intracellular Infection. J Immunol 196: 375–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tian Y, and Zajac AJ. 2016. IL-21 and T Cell Differentiation: Consider the Context. Trends in immunology 37: 557–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hildeman DA, Zhu Y, Mitchell TC, Bouillet P, Strasser A, Kappler J, and Marrack P. 2002. Activated T cell death in vivo mediated by proapoptotic bcl-2 family member bim. Immunity 16: 759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snow AL, Oliveira JB, Zheng L, Dale JK, Fleisher TA, and Lenardo MJ. 2008. Critical role for BIM in T cell receptor restimulation-induced death. Biol Direct 3: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin H, Carrio R, Yu A, and Malek TR. 2004. Distinct activation signals determine whether IL-21 induces B cell costimulation, growth arrest, or Bim-dependent apoptosis. J Immunol 173: 657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barker BR, Gladstone MN, Gillard GO, Panas MW, and Letvin NL. 2010. Critical role for IL-21 in both primary and memory anti-viral CD8+ T-cell responses. Eur J Immunol 40: 3085–3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coquet JM, Skak K, Davis ID, Smyth MJ, and Godfrey DI. 2013. IL-21 Modulates Activation of NKT Cells in Patients with Stage IV Malignant Melanoma. Clin Transl Immunology 2: e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tahir SM, Cheng O, Shaulov A, Koezuka Y, Bubley GJ, Wilson SB, Balk SP, and Exley MA. 2001. Loss of IFN-gamma production by invariant NK T cells in advanced cancer. J.Immunol. 167: 4046–4050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dhodapkar MV, Geller MD, Chang DH, Shimizu K, Fujii SI, Dhodapkar KM, and Krasovsky J. 2003. A Reversible Defect in Natural Killer T Cell Function Characterizes the Progression of Premalignant to Malignant Multiple Myeloma. J.Exp.Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Exley MA, Friedlander P, Alatrakchi N, Vriend L, Yue SC, Sasada T, Zang W, Mizukami Y, Clark J, Nemer D, LeClair K, Canning C, Daley H, Dranoff G, Giobbie-Hurder A, Hodi FS, Ritz J, and Balk SP. 2017. Adoptive Transfer of Invariant NKT Cells as Immunotherapy for Advanced Melanoma: a Phase 1 Clinical Trial. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timmerman JM, Byrd JC, Andorsky DJ, Yamada RE, Kramer J, Muthusamy N, Hunder N, and Pagel JM. 2012. A phase I dose-finding trial of recombinant interleukin-21 and rituximab in relapsed and refractory low grade B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 18: 5752–5760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.