Abstract

Activated platelets release functional, high molecular weight Epidermal Growth Factor (HMW-EGF). Here, we show platelets also express EGF receptor (EGFR) protein, but not ErbB2 or ErbB4 co-receptors, and so might respond to HMW-EGF. We found EGF stimulated platelet EGFR autophosphorylation, PI3 kinase-dependent AKT phosphorylation, and a Ca++ transient that were blocked by EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibition. Strong (thrombin) and weak (ADP, PAF) G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) agonists and non-GPCR collagen recruited EGFR tyrosine kinase activity that contributed to platelet activation since EGFR kinase inhibition reduced signal transduction and aggregation induced by each agonist. EGF stimulated ex vivo adhesion of platelets to collagen-coated microfluidic channels, while systemic EGF injection increased initial platelet deposition in FeCl3-damaged murine carotid arteries. EGFR signaling contributes to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) tumorigenesis, but the source of its ligand is not established. We find individual platelets were intercalated within OSCC tumors. A portion of these platelets expressed stimulation-dependent Bcl-3 and IL-1β, and so had been activated. Stimulated platelets bound OSCC cells, and material released from stimulated platelets induced OSCC epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stimulated their migration and invasion through Matrigel® barriers. Anti-EGF antibody or EGFR inhibitors abolished platelet-induced tumor cell phenotype transition, migration, and invasion, so the only factor released from activated platelets necessary for OSCC metastatic activity was HMW-EGF. These results establish HMW-EGF in platelet function and elucidate a previously unsuspected connection between activated platelets and tumorigenesis through rapid—and prolonged—autocrine-stimulated release of HMW-EGF by tumor-associated platelets.

Keywords: Epidermal Growth Factor, Thrombosis, tumor infiltration, platelet activation

Introduction

Platelets are fundamental components of the inflammatory system that express hundreds of mediators, cytokines, and growth factors after activation (1, 2) to modulate both innate and adaptive immune systems (3). EGF is a prominent member of the biologically active proteins released from stimulated platelets (4–6), and platelets are the only source of EGF in blood (4, 7–9). Platelets, however, do not contain soluble, fully processed 6 kDa EGF, but instead the transmembrane ~140 kDa pro-EGF precursor is abundantly immobilized on their surface (10). The protease ADAMDEC1 released from stimulated platelets solubilizes this pro-EGF to high (~130 kDa) molecular weight (HMW)-EGF (10), the form of EGF present in serum (8, 11, 12). The carboxyl terminus of HMW-EGF is the EGF domain, and HMW-EGF is an active EGFR ligand (10).

Cancer-associated venous thromboembolism is common, occurring in one of every five patients with cancer (13), and is the leading cause of death after that from the tumor itself. This cancer-related coagulopathy, broadly Trousseau’s syndrome, can aid tumorigenesis (14–16) through the release of hundreds of stored proteins and non-protein mediators from activated platelets (1, 2). Accordingly, thrombosis has long (17, 18) been known to contribute to metastasis (19, 20) and tumor angiogenesis (21). Platelets accumulate in intra-vascular thrombi in damaged vessels, but stimulated platelets are motile cells (22–25), and platelets penetrate the vascular barrier when activated (26). Accordingly, intact platelets accumulate in the subendothelial space of human tissue (27, 28) and within murine ovarian tumors (29).

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is the 6th most common cancer worldwide (30), with 80-90% of these cancers over-expressing EGFR that contributes to OSCC tumorigenesis and metastasis (31–33). EGFR expression in these tumors correlates to poorer prognosis and radiation resistance (34), and an early approved use of the anti-EGFR antibody Cetuximab was for head and neck cancers (31). While EGF is the paradigmatic growth-promoting cytokine, few cells express its mRNA (35) so the source of EGFR ligand for these tumors is opaque. Oral cancers, however, are marked by an extensive immune cell infiltration (36), and the number of blood-borne platelets associate with oral cancer progression and survival (37), so potentially platelets introduce EGFR ligand into these tumors.

We explored the potential for platelets to contribute EGF to tumorigenesis to find activated platelets populate oral squamous cell carcinomas, that platelet-derived HMW-EGF promotes OSCC cell epithelial mesenchymal transition to a migratory phenotype, and that blockade of EGFR abolishes OSCC cell invasion and migration in response to materials released from activated platelets. We also find platelets express functional EGF tyrosine kinase receptors that aid signaling and activation by diverse agonists, and so conclude tumor-infiltrating platelets can function in an autocrine loop to promote tumor cell migration.

Material and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Endotoxin-free human serum albumin (25%) was from Baxter Healthcare. Anti-EGF, anti-EGFR, anti-Her2, anti-HER3, anti-Her4, anti-β-actin, anti-Akt, anti-Akt Thr308, anti-Akt Ser473, anti-pEGFR, anti-Snail, anti-Claudin-1, and anti-horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers MA). EGF was obtained either from R&D Systems (Minneapolis MN) or Cell Signaling Technology. The CL4 anti-EGFR aptamer was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IW). Ly294002 was from Cell Signaling Technology, protease inhibitor mix was from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis IN), while Fura2-AM and Calcein-AM were from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham MA). Thrombin and collagen were from Chrono-log (Havertown PA), while media and sterile filtered HBSS were prepared by the Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute media preparation core. We obtained microfluidic Vena8 Fluoro+ chips from Cellix Limited (Dublin, Ireland), while AG1478, PGE1, SDS, and all other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis MO). Recombinant ADAMDEC1 was purified from CHO cell supernatants stably transfected with ADAMDEC1 (Origen, Rockville, MD). SAS-H1, SAS-L1, and SCC9 cells were from tongue squamous cell carcinomas of separate patients, HSC-3 from a poorly differentiated human oral squamous cell carcinoma cell with cervical lymph node metastasis, and FaDu (ATCC) was from human pharynx oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. TR146 lymph node-infiltrating buccal squamous cell carcinoma cell line (38) has been previously described (39). BioCoat™ Matrigel™ Invasion Chambers were from Corning (Oneonta NY).

Platelet preparation

Human blood was drawn into acid-citrate-dextrose and centrifuged (200 x g, 20 min) without braking to obtain platelet-rich plasma in a protocol approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. Purified platelets were prepared from this platelet-rich plasma as in the past (40) where platelet-rich plasma was filtered through two layers of 5-μm mesh (BioDesign) to remove nucleated cells and recentrifuged (520 x g, 30 min) in the presence of 100 nM PGE1. The pellet was resuspended in 50 ml PIPES/saline/glucose (5 mM PIPES, 145 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 50 μM Na2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5.5 mM glucose) containing 100 nM PGE1 before these cells were centrifuged (520 x g, 30 min). The recovered platelets were resuspended in 0.5% human serum albumin in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS).

Platelet function

Washed platelets (2.5 x 108/ml) were stimulated with 0.02 to 0.05 U thrombin (the minimally active amount determined daily for each donor), 1 μM PAF, or 10 μg collagen. Platelet aggregation was measured by transmittance (Chronolog) with stirring (1,000 rpm). Adhesion was measured by pre-incubating washed platelets with Calcein-AM (1 μg/ml) for 10 min before incubating cells on a glass cover slip previously coated with bovine serum albumin (100 μg/ml). Some cells were pre-treated with 2 μM AG1478 or 10 μM Ly294002 for 10 min to inhibit EGFR or PI3K, respectively, and then stimulated, or not, with 2 ng/ml EGF. Cells were imaged by fluorescent microscopy with total fluorescence quantitated by ImageJ software. Ca++ transients were measured in stirred Fura2-AM labeled platelets with the ratio of emission at 510 nanometers quantified after excitation at either 340 or 380 nanometers in a custom Photon Technology International (Birmingham NJ) fluorimeter. Flow through Cellix collagen-coated microfluidic chambers was at 63 Dynes and fluorescent platelet deposition in the capillaries was quantified as before (41).

Intravascular thrombosis

C57Bl/6 mice were anesthetized (100 mg/kg ketamine/10 mg/kg xylazine) before the right jugular vein and the left carotid artery were exposed by a middle cervical incision in a protocol approved by the Cleveland Clinic IACUC. Platelets were labeled by injecting 100 μl rhodamine 6G (0.5 mg/ml) in saline, with or without EGF (10 μg/kg), into the right jugular vein (42, 43). Thrombosis was induced 10 min later in the left carotid artery by topical application of a filter paper (1 x 2 mm) saturated with 7.5% FeCl3 for 1 minute before washing, with the resulting fluorescent thrombus formation observed in real-time under a water immersion objective at 10 X magnification. Time to occlusive thrombosis was determined offline using video images captured with a QImaging Retigo Exi 12-bit mono digital camera (Surrey, Canada) and Streampix version 17.2 software (Norpix, Montreal, Canada). Fluorescent intensity was analyzed by ImageJ in 3 to 4 randomly selected images for statistical analysis.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Human oral cancer biopsy blocks were obtained from Department of Pathology, School of Dental Medicine Case Western Reserve University with IRB exemption from the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center. Immunofluorescence staining was performed as described previously (44). Briefly, sections (5 μm) were de-paraffinized in xylene and hydrated with serially diluted ethanol, followed by blocking with 10% donkey serum overnight at 4°C. After washing with phosphate buffered saline, the sections were incubated with the respective primary antibody (1 h, 24°), washed in phosphate buffered saline, and then stained with the stated fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibody. The consecutive staining by different primary and secondary antibodies was performed using the same protocol. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA). Isotype controls were conducted using isotype-matched IgGs, corresponding to each primary antibody. Immunofluorescent images were generated using a Leica DMI6000B automated inverted fluorescence microscope and processed with NIH ImageJ.

Western blotting

Washed platelets (4 x 108) were treated or not with the stated agonists before the cells were lysed in reducing SDS loading buffer. For some experiments, platelets were pre-incubated with 2 μM AG1478 in DMSO, Ly294002 in DMSO, or DMSO as their solvent control for 10 min at 24°C. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE in 4 to 20% cross-linked gels, the proteins transferred to PVDF membranes and probed with the stated primary antibody overnight and then detected with immunoreactive horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody.

Expression of data and statistics

Experiments were performed at least three times with cells from different donors, and all assays were performed in triplicate. The standard errors of the mean from all experiments are presented as error bars. Figures and statistical analyses were generated with Prism4 (GraphPad Software). A value of p≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

EGF is an unappreciated pro-thrombotic platelet agonist

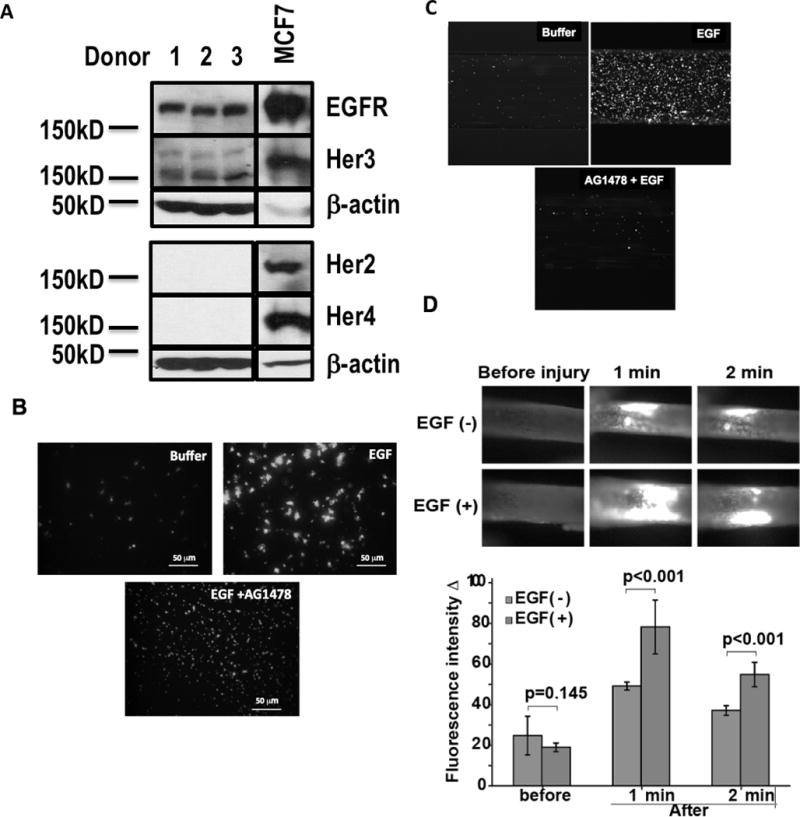

We determined whether platelets express EGF receptors, and so might respond to the HMW-EGF they release (10). We immunoblotted platelet lysates for EGFR (ErbB1, Her1) and its family members ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4. This revealed (Fig. 1A) that the platelet proteome contained EGFR and its inactive ErbB3 family member that lacks a receptor tyrosine kinase domain. Correspondingly, a recent quantitative compilation of the platelet proteome identified EGFR peptides (2), although an earlier quantitative mass spectrometric enumeration of platelet proteins did not include this receptor (45). Platelets did not express the EGFR family members Her2 or Her4, in contrast to the positive control MCF7 cells that expressed all four receptors, which limits the potential response of platelets to EGF related ligands that are recognized by EGFR homodimers. EGFR expression in the absence of other family members was apparent among several individual blood donors.

Figure 1. Platelets express EGFR and respond to EGF.

A. Platelets express EGFR. Proteins in the lysates of equivalent numbers of quiescent platelets were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for the EGFR family (Her2, Her3, Her4, EGFR) or β-actin as described in “Materials and Methods.” MCF7 cells are a positive control that express all EGFR family members. (n=3). B. EGF induces platelet adhesion. Platelets were labeled with the Ca++ sensitive dye Calcein-AM, treated or not with AG1478 to inhibit EGFR tyrosine kinase activity, and then incubated with EGF (200 ng/ml). These cells were then layered over albumin-coated glass slides, which suppress adhesion of quiescent platelets. Non-adherent cells were removed after 10 min by washing before Calcein fluorescence was imaged. (n=3) C. EGF stimulates platelet adhesion to collagen at high shear flow. Calcein-AM-labeled platelets were pulled through collagen-coated Cellix microfluidic channels at 63 Dynes with or without EGF and with or without AG14778 added at the initiation of flow. The assay was terminated after 5 min by pulling buffer through the channels and then imaging fluorescence at the chamber’s exit. (n=3) D. EGF augments intravascular thrombosis. Mice were injected with rhodamine 6G to fluorescently label platelets, with or without accompanying EGF (10 mg/kg), 10 min prior to ectopic application of FeCl3 to surgically exposed carotid arteries to initiate thrombosis (42, 43). Frames from fluorescent videomicroscopy at the stated times after initiation of thrombosis show rapid deposition of fluorescent platelets at the site of injury that was significantly enhanced by prior EGF injection.

We determined whether platelet EGFR was functional to find that EGF stimulated Calcein-labeled platelets to adhere to a normally non-adherent albumin-coated surface (Fig. 1B). This response included the appearance of large aggregates displaying increased Ca++-dependent Calcein fluorescence, suggesting active adhesion and not just agglutination. EGF-induced adhesion was suppressed by the long established (46) EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 (tyrphostin). We next modeled the pro-thrombotic effect of EGF by flowing washed human platelets through collagen-coated Cellix microfluidic chambers at high shear. EGF increased adhesion of fluorescently labeled platelets along the length (not shown) and distal end of the chamber (Fig. 1C). Pre-treating platelets with AG1478 abolished the EGF-stimulated increase in platelet deposition in the collagen-coated microfluidic chambers. EGF was similarly active in an in vivo model of carotid artery thrombosis. We found that injecting EGF into mice 10 min prior to initiating thrombosis by a brief ectopic application of FeCl3 to carotid arteries enhanced deposition of fluorescently labeled platelets onto the vessel wall early in the thrombotic process (Fig. 1D). Injected EGF did not alter the time to occlusive thrombosis (not shown), so EGF only augmented deposition of platelets during the initial phase of unstable thrombus formation.

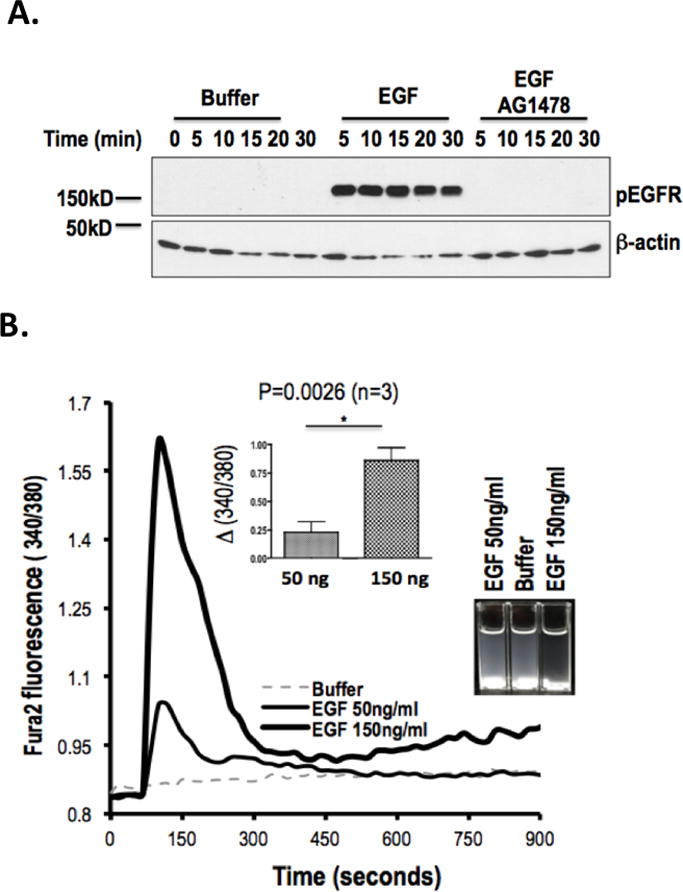

EGF stimulates platelet EGFR

We determined whether EGF stimulated platelets through their EGFR by detecting the phosphorylation of select EGFR tyrosyl residues (47) since autophosphorylation of these residues is an immediate response to EGFR homodimerization and activation (48). We used a mixture of antibodies that recognize five of these phosphorylated tyrosyl residues in activated EGFR to find these residues were not phosphorylated in quiescent platelets (Fig. 2A). Recombinant EGF, however, stimulated phosphorylation of EGFR tyrosyl residues within 5 min, the earliest time we tested, with abundant phosphorylation remaining by 30 min. Pre-treating platelets with AG1478 abolished EGF-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of platelet EGFR, so phosphorylation indeed reflected autophosphorylation as in the positive control HeLa cells reporter cells (10).

Figure 2. EGFR is a platelet agonist.

A. EGF stimulates tyrosine autophosphorylation of platelet EGFR. Platelets were incubated (10 min) with DMSO or AG1478 in DMSO, and then with buffer or EGF (200 ng/ml) for the stated times. Proteins in lysed platelets were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for phosphorylated EGFR with a mixture of 5 anti-phosphotyrosyl-EGFR antibodies or with β-actin. (n=3) B. EGF stimulates platelet Ca++ transients and adhesion. Fura2-AM labeled platelets were stimulated with the stated concentration of EGF and the fluorescent ratio at 510 nmeters after excitation at either 340 or 380 nmeters was assessed over time. INSERT. Fluorescence was significantly higher after stimulation with 150 ng/ml than 50 ng/ml recombinant EGF. (n=3) Cuvettes at the end of the experiment showed clearing of opalescent washed platelets in the cuvettes after EGF exposure.

EGFR stimulation rapidly increases intracellular Ca++ in nucleated cells (49, 50) and a Ca++ flux is central to platelet activation (51). We thus determined whether EGFR signaling altered Ca++ metabolism in platelets by pre-labeling these cells with the ratiometric Ca++ sensitive dye Fura2-AM, washing the cells, and then stimulating them with EGF. We found EGF induced a rapid, concentration-dependent, and significant increase in the 340/380 nmeter ratio of Ca++-FURA2 fluorescence (Fig. 2B), showing EGF induced a rapid spike in intracellular Ca++ levels in platelets. Visualization of the cuvettes at the end of the experiment showed clearing of opalescent suspended cells with formation of adherent aggregates on the walls of the fluorimeter cuvettes and stir bar (Fig. 2C inset) supporting the conclusion that platelets functionally respond to EGFR stimulation.

EGFR transactivation aids thrombin-induced signal transduction

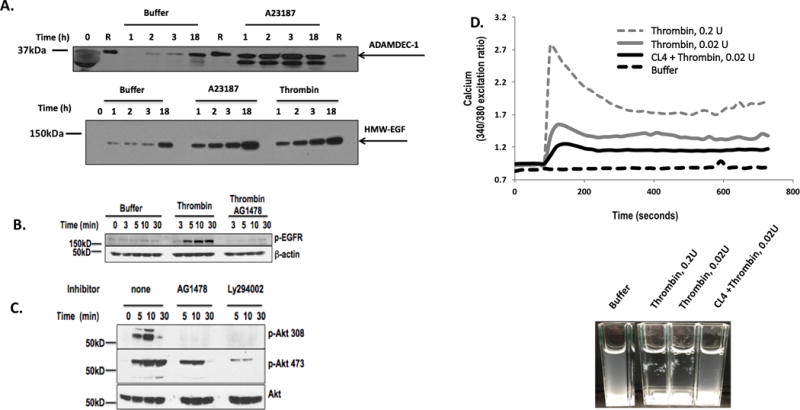

Platelet activation and their subsequent release of stored proteins, small molecules, and polymers by degranulation is immediate and is complete within several minutes of stimulation (6). HMW-EGF release, however, was different with continued release of soluble HMW-EGF for up to 18 h after either pharmacologic stimulation by the Ca++ ionophore A23187 or the strong agonist thrombin (Fig. 3A). The protease ADAMDEC1, which hydrolyzes membrane-bound pro-EGF to release soluble HMW-EGF (10), also continued for hours after stimulation. Unstimulated platelets eventually released both ADAMDEC1 and HMW-EGF, potentially reflecting IL-1β synthesis and autocrine stimulation of the platelet IL-1 receptor (52).

Figure 3. Platelet EGFR aids thrombin-induced signaling.

A. Platelets release HMW-EGF for extended times after activation. Platelets were incubated with buffer, the Ca++ ionophore A23187 (1 μM), or active human thrombin (0.05U) for the stated times before the media was cleared of platelets by centrifugation. Platelet-derived supernatants were denatured by SDS solubilization with RIPA buffer and the proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE in 4 to 20% crosslinked SDS gels, and immunoblotted for HMW-EGF (top) or ADAMDEC1(bottom) (n=3). Lanes designated with “R” contained recombinant ADAMDEC1. B. Thrombin stimulates EGFR tyrosine autophosphorylation. Platelets were incubated (10 min) with DMSO or 2 μM AG1478 in DMSO and then with buffer or thrombin (0.05 U/ml) for the stated times. Proteins in lysed platelets were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for phosphorylated EGFR with a mixture of 5 anti-phosphotyrosyl-EGFR antibodies. (n=3) C. Platelet EGFR autophosphorylation is necessary for thrombin-stimulated AKT T308 phosphorylation. Washed human platelets were pre-incubated (10 min) with buffer, 2 μM AG1478, or 10 μM Ly294002 to inhibit PI3K and then stimulated with thrombin (0.05 U/ml) for the stated time. Platelets were lysed, their proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted for phosphorylation of AKT threonine 308 (top), AKT serine 473 (middle), or total AKT (bottom). (n=3) D. EFGR signaling contributes to thrombin-stimulated Ca++ flux. Washed platelets were loaded with Fura2 and then washed. These cells were then pre-treated or not with the anti-EGFR aptamer CL4 (200 nM) before stimulation with stirring in cuvettes with buffer or the stated thrombin (IIa) concentration as the ratio of fluorescence was assessed over time after excitation at 340 or 380 nmeters. Inset Thrombin-stimulated aggregation in the fluorimeter cuvettes was suppressed by the anti-EGFR RNA aptamer CL4. n=3

EGFR is trans-activated in a range of cells by G protein-coupled receptor (GPCRs) stimulation (53) that then aids (54–57), or circumvents (55), signaling in response to these GPCRs. Thrombin activates human platelets primarily through the GPCR protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR1) (58), and we found thrombin rapidly induced tyrosine phosphorylation of platelet EGFR (Fig 3B). Thrombin-induced EGFR phosphorylation was abolished by pretreating platelets with AG1478, so thrombin transactivated EGFR autophosphorylation in platelets. Thrombin stimulation induced phosphorylation of the serine/threonine kinase AKT at threonine 308 and this required EGFR tyrosine kinase activity since inclusion of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 abolished phosphorylation of this residue (Fig. 3C). In contrast, phosphorylation of AKT serine 473 in response to thrombin stimulation was reduced, but not abolished, in the absence of functional EGFR. Phosphorylation at both AKT sites was downstream of PI3 kinase activity since Ly294002 effectively inhibited thrombin-induced AKT phosphorylation of either residue. We determined that the anti-EGFR ribonucleotide aptamer CL4, which inhibits EGF ligation and activation (59), also suppressed the thrombin stimulated flux in intracellular Ca++ (Fig. 3D). We also observed that the CL4 aptamer strongly interfered with the formation of platelet aggregates in the fluorimeter cuvettes by the end of the experiment (Fig. 3D). Thus, EGFR ligation, autophosphorylation, and activation aid thrombin-induced signaling cascades.

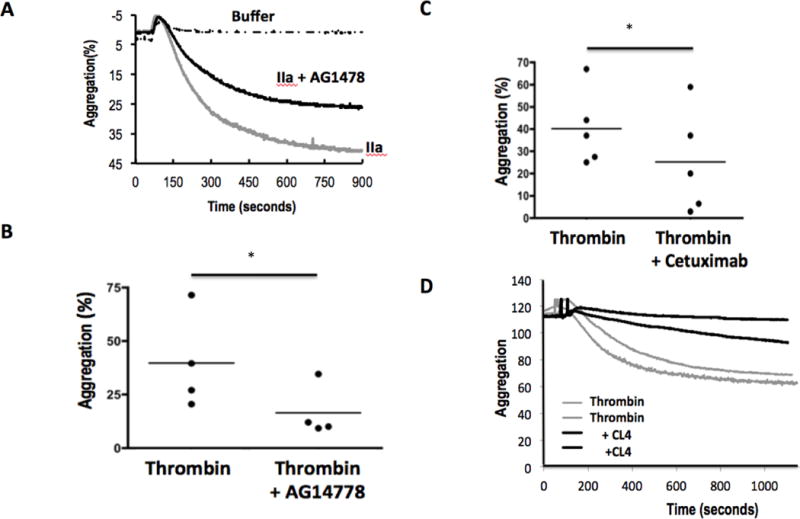

EGFR contributes to thrombin-induced platelet aggregation

We determined whether EGFR signaling was sufficiently rapid to contribute to immediate thrombin-induced aggregation. We pre-treated washed platelets with AG1478 and then stimulated aggregation of these cells with a low dose of thrombin to find that AG1478-treated platelets were significantly less able to undergo homotypic aggregation (Fig. 4A). The relative contribution of EGFR kinase activity to thrombin-stimulated aggregation was variable among blood donors, but overall its contribution was significant (Fig. 4B). The humanized chimeric monoclonal antibody Cetuximab physically ligates EGRF to interfere with EGF binding, thereby suppressing EGFR signaling. Cetuximab significantly reduced aggregation of platelets from varied donors in response to thrombin stimulation (Fig. 4C). Correspondingly, we found the anti-EGFR CL4 RNA aptamer, which also suppresses EGF ligation to EGFR, suppressed thrombin-induced platelet aggregation (Fig. 4D), so EGFR materially contributes to thrombin-induced platelet responsiveness.

Figure 4. EGFR aids thrombin-induced aggregation.

A. Time relationship of platelet aggregation in the presence or absence of EGFR tyrosine kinase activity. Washed human platelets were pre-treated with DMSO or AG1478 in DMSO for 10 min with stirring before addition of buffer or thrombin (0.05U). Optical transmittance was assessed over time in stirred Chrono-log cuvettes. B. Loss of EGFR function reduces aggregation of platelets from multiple donors. Platelets were pre-treated with AG1478, or not, before the change in optical density between buffer and fully aggregated platelets 900 seconds after activation was assessed. * p<0.05 n=4 C. Cetuximab inhibits thrombin-induced aggregation. Platelets from multiple donors were pre-treated (10 min) or not with the anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody Cetuximab (20μg) before the cells were stimulated with buffer or thrombin as above. * p<0.05 n=5 D. CL4 aptamer inhibition of EGFR reduces aggregation in response to thrombin. Duplicate platelet aliquots were treated with 200 nM of the RNA anti-EGFR aptamer CL4 for 1 h before aggregation was initiated by the addition of thrombin as above. n=3

EGFR transactivation aids platelet activated by GPCR and non-GPCR ligands

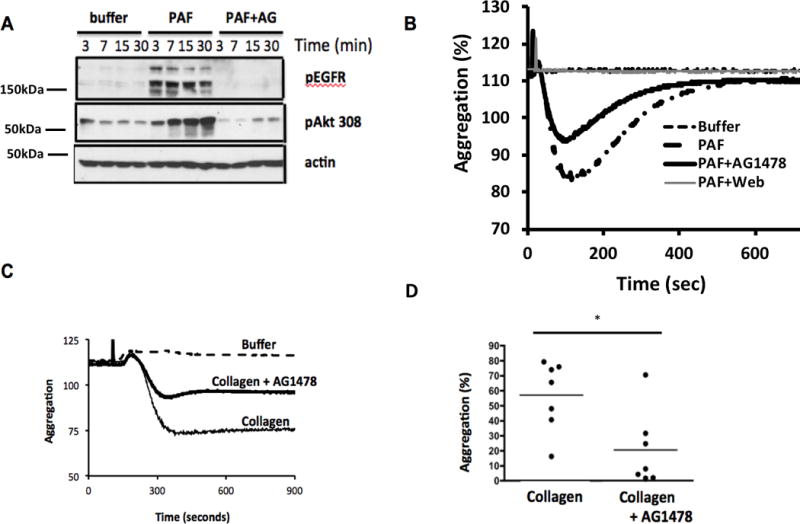

The phospholipid mediator Platelet-activating Factor (PAF) ligates and stimulates PtAFR, a distinct and poorly conserved member of the GPCR family of receptors (60), expressed by platelets and other cells of the innate immune system (61). We found PAF induced phosphorylation of EGFR tyrosyl residues, and again this represented autophosphorylation because phosphorylation was abolished by AG1478 pre-treatment (Fig. 5A). PAF stimulated AKT threonine 308 phosphorylation, although this was more prolonged than in response to thrombin stimulation, and we found AG1478 also strongly, but not completely, suppressed phosphorylation of this downstream kinase. EGFR signaling contributed to PAF-stimulated platelet function since AG1478 pre-treatment reduced aggregation, although this suppression was far less than complete blockade of the PAF binding site of PtAFR by the small molecule WEB2086 (Fig. 5B). Platelets are activated by collagen through non-GPCR GPVI and the integrin dimer α2β1 that recruit soluble Src tyrosine kinase activity, activation of PI3 kinase, and a rapid increase in intracellular Ca++ (62, 63). Pre-treating platelets with AG1478 significantly reduced subsequent aggregation in response to collagen stimulation (Fig. 5C). This effect was common among platelets of varied blood donors (Fig. 5D), so EGF transactivation extends to non-GPCRs, at least in human platelets.

Figure 5. EGFR tyrosine kinase activity contributes to PAF- and collagen-induced aggregation.

A. Platelet-activating Factor (PAF) induces EGFR autophosphorylation. Washed human platelets were pre-incubated with buffer or 2 μM AG1478 and stimulated with the lipid agonist PAF for the stated times. Lysates were resolved and immunoblotted for phospho-EGFR or phospho-AKT Thr308 as in Figure 3. (n=3) B. EFGR contributes to PAF receptor induced aggregation. Washed platelets, pre-treated or not with AG1478 (2 μM, 10 min) or the specific PtAFR inhibitor WEB2086 before aggregation was assessed by turbidimetry. n=3 C. EFGR contributes to collagen induced aggregation. Washed platelets, pre-treated or not with AG1478 (2 μM, 10 min), were stimulated with buffer or collagen (10 μg/ml) before turbidity was assessed over time. The full deflection induced by PAF was abolished by WEB2086 and reduced by AG1478. D. EGFR contributes to platelet aggregation from multiple donors. Aggregation was assessed as in the previous panel and expresses as a fraction of full aggregation. * p<0.05 n=4

Platelets localize within OSCC microenvironments

Activated platelets are repositories of a myriad of growth factors and mediators, and are a source of HMW-EGF. We determined whether platelets are present in tumor tissue to first find that normal oral mucosa contains few extravascular platelets, identified by their abundant and specific surface marker CD42b (GP1bα) (Fig. 6A). In contrast, anucleate CD42+ (red) platelets accumulated within the tumor microenvironment in the early stages (T0/T1) of oral squamous cellular carcinoma (OSCC) (Fig. 6B). Macrophage-rich infiltrates line the margins of OSCC tumors (64), and staining for the macrophage/monocytic marker CD68 identified a macrophage-rich margin, but also anucleate CD68 and CD42b positive (yellow/orange) platelets, which additionally express CD68 (2, 45), within the tumor (Fig. 6C). Infiltration of CD68 tumor associated macrophages, as well as CD42b positive anuclear platelets, was common among OSCC tumors of several patients (Fig. 6C-E). Typically, platelet activation in vivo is not readily discernable, but we do know quiescent platelets contain neither IL-1 β mRNA (65) nor protein (45), while activation promotes splicing of stored IL-1β heteronuclear RNA to functional mRNA and translation of this newly formed mRNA to functional IL-1β protein (40, 65, 66). Immunohistochemistry showed a portion of the anucleate CD42+ cells distributed throughout the OSCC tumor contained IL-1β protein (Fig. 6D). Bcl-3 expression additionally marks activated platelets since Bcl-3 is only is translated from stored mRNA in activated platelets (67–69) and is not present in the proteome of unactivated platelets (2, 45). Immunohistochemistry shows regions of the OSCC tumor contained individual platelets that co-expressed CD42 and Bcl-3 (Fig. 6E), so activated platelets populate OSCC tumors.

Figure 6. Oral squamous cell carcinomas contain activated platelets.

A. Normal human tongue does not contain immunoreactive platelets. Sections of normal human tongue immunostained for endothelial/hematopoietic cell CD34 (mucrosialin, green) or platelet CD42b (gp1bα, red), and counterstained nuclear DAPI (purple) dye. B. Platelets infiltrate OSCC tumors. Platelet and hematopoietic cell in an early stage (T0/T1) patient OSCC stained with anti-CD34, anti-CD42b, and DAPI as in the preceding panel. C. Platelets infiltrate OSCC tumor, not macrophage-rich margins. Poorly differentiated OSCC section stained with anti-CD68 (monocytes, platelets; green) or anti-CD42b (platelet; red) and counterstained with DAPI. D. OSCC from a second patient contain CD42b positive platelets distinct from nucleated CD68 expressing macrophages. E. OSCC from a third patient contain CD42b positive platelets distinct from CD68 expressing macrophages. F. OSCC tumors from patient 1 tumor contain activated platelets marked by IL-1β. OSCC sections were stained with anti-IL-1β (green) or anti-CD42b (red), and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. G. OSCC tumors from patient 1 contain activated platelets expressing Bcl-3. OSCC sections were stained with anti-Bcl-3 (green) or anti-CD42b (red), and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI.

Platelet-derived HMW-EGF stimulates OSCC cell invasion and migration

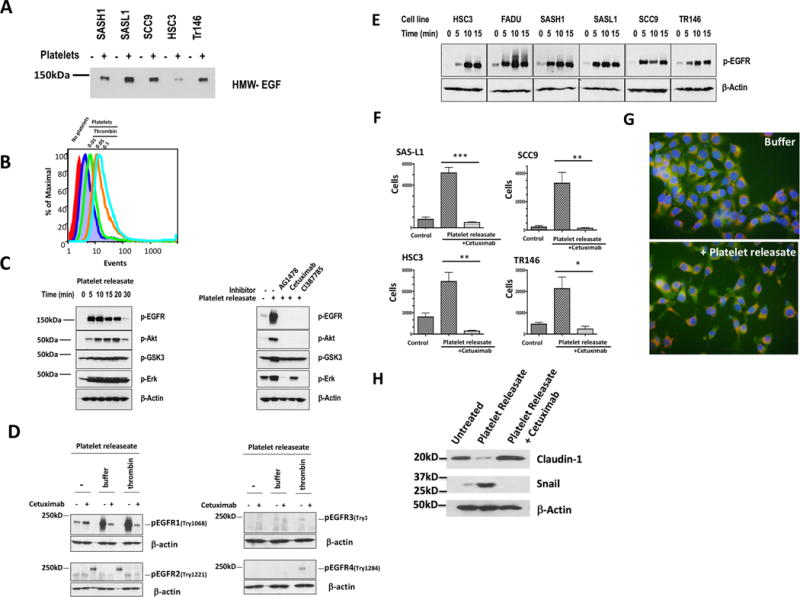

Expression of EGF mRNA is uncommon (70), and OSCC lines from tumors of different patients themselves failed to released immunoreactive EGF (Fig. 7A). In contrast, soluble HMW-EGF was available to each of these cell lines after co-incubation with thrombin-stimulated platelets. These two cell types can come into proximity since flow cytometry showed stimulated platelets adhered to the SASH-1 OSCC line (Fig. 7B). Material from these activated platelets rapidly stimulated phosphorylation of OSCC tumor cell EGFR, but also downstream AKT, GSK3, and ERK kinases (Fig. 7C). Stimulation of tumor cell EGFR by platelet-derived material was primarily responsible for phosphorylation of these kinases since blockade of EGFR tyrosine kinase activity by AG1478, the irreversible EGFR inhibitor Cl387785, or the clinically used anti-EGFR antibody Cetuximab all at least returned phosphorylation of these kinases to their basal level (Fig. 7C). Activated platelets selectively stimulated OSCC cell EGFR, and not other EGFR family members in HeLa reporter cells that express all EGFR family members (Fig. 7D), so HMW-EGF is the only functional EGFR family ligand released from activated platelets. Platelet releaseate activated EGFR phosphorylation of cell lines derived from diverse head and neck tumors (Fig. 7E), although this response was delayed for the HSC3 and Tr146 cell lines, which contained less immunoreactive HMW-EGF when cultured with platelet releaseates (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7. Platelet-derived HMW-EGF induces epithelial mesenchymal transition of oral squamous cell carcinoma lines.

A. Platelets, but not OSCC cells, release HMW-EGF. OSCC cell lines were incubated (16 h) with or without addition of cell-free thrombin-activated releaseates before supernatant proteins were resolved by SDS/gradient gel electrophoresis. EGF immunoreactivity was visualized with anti-EGF antibody and detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. n=3 B. Thrombin-activated platelets bind SAS-H1 OSCC cells. Washed human platelets labeled with Calcein-AM were incubated with Cellstripper-suspended SAS-H1 cells before thrombin (0.05U), or a buffer control, was added for 10 min before the cells were washed and lightly fixed with paraformaldehyde. A gate for SAS-H1 cells was defined by forward and side scatter before Calcein fluorescence in channel 1 in this gate was quantified by flow cytometry. n=2 C. Platelet HMW-EGF stimulates OSCC EGFR activation and downstream signaling. SCC9 cells were stimulated for the stated times with releaseates from thrombin-stimulated platelets before the cells lysed and their proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. The transferred proteins were immunoblotted with anti-phospho-EGFR, phospho-AKT, phospho-GSK3, phospho-ERK, or anti-β-actin antibodies. In some cases, OSCC cells were pre-treated with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478, humanized anti-EGFR antibody Cetuximab, or the irreversible EGFR inhibitor CL1387785 as stated. n=3 D. Activated platelet releaseate contains EGFR agonist, but not agonists for other EGFR family members. HeLa cells expressing all ErbB receptors were treated (15 min) with Cetuximab (20 μg), or not, and stimulated (10 min) in buffer or concentrated (>50k Da) media from nominally unstimulated or thrombin stimulated platelets. The reaction was terminated with RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors before cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted for the stated phosphorylated proteins or β-actin. n=3 E. Platelet releaseates stimulate EGFR phosphorylation in diverse OSCC cell lines. The stated OSCC cell lines were stimulated for increasing times with releaseates from thrombin-stimulated platelets before western blotting total cellular proteins with anti-EGFR phospho-tyrosyl1068 or anti-β-actin antibodies. n=3 F. Activated platelet releaseates stimulate OSCC cell invasion and migration through EGFR signaling. OSCC cells (2.5 x 104), containing 20 μg Cetuximab or not, were inoculated into the upper well of a Corning Biocoat™ Matrigel® invasion chamber above a lower chamber containing releaseates from thrombin-stimulated platelets. Cells adherent to the bottom of the lower chamber after 48 h incubation were released by trypsin digestion and manually counted with the aid of a hemocytometer. The mean ± SD of two combined biologic replicates containing 3 samples are presented. *** p=0.0001, ** p < 0.001, *, p< 0.01. G. Platelet releaseates stimulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition migratory phenotype in SAS-H1 OSCC cells. SAS-H1 cells were labeled with Calcein-AM and Mitotracker™ Red and then with buffer or thrombin-stimulate platelet releaseate for 16 h before the cells were imaged by fluorescent microscopy. H. Platelet-derived EGF bioactivity promotes markers of epithelial to mesenchymal transition. FaDu OSCC cells were grown with releaseate from activated platelets, or not, in the absence or presence of anti-EGF antibody Cetuximab (20 μg) for 48 h prior to lysis. Abundance of Claudin-1 and Snail were visualized by western blotting relative to β-actin content.

The physiology of differentiated tumor cells can be reverted to a migratory, pro-invasive phenotype through epithelial to mesechymal transition that is primarily mediated by EGFR signaling (71). We found diverse OSCC cell lines were attracted by releaseates from activated platelets through a Matrigel® barrier and then through a Millipore filter as measures of both invasion and migration (Fig. 7F). Inclusion of the humanized anti-EGF monoclonal antibody Cetuximab abolished stimulated invasion, while allowing basal numbers of cells to invade the lower chamber, so HMW-EGF is the only agonist released from stimulated platelets to stimulate metastatic behavior of cells from diverse OSCC tumors.

We tested whether platelet HMW-EGF altered OSCC cellular architecture, reflecting the epithelial to mesenchymal transition, by labeling SAS-H1 OSCC cells with Calcein to identify cytoplasm and Mitotracker™ Red to visualize organelle distribution. We found supernatants from stimulated platelets induced the elongated migratory phenotype of SAS-H1 cells compared to the cluster of compact cells not exposed to platelet-derived material (Fig. 7G). This spindle shape cell after exposure to platelet releaseate correlated to an increased level of green fluorescence, suggesting intracellular Ca++ levels were enhanced in these cells. Molecular markers reflecting loss of intercellular adhesion molecule Claudin-1 of mature epithelium tight junctions or accumulation of the transcriptional repressor Snail that enables expression of mesenchymal mediators confirmed induction of OSCC epithelial to mesenchymal transition by material released from thrombin-activated platelets (Fig. 7H). Inclusion of the anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody Cetuximab abolished Snail accumulation and fully restored Claudin-1expression, so, again, the only factor relevant to induction of an invasive OSCC tumor cell phenotype released by stimulated platelets was HMW-EGF.

DISCUSSION

Platelets are reported to be unable to bind EGF (72), but we find by western blotting that platelets did express EGFR, although perhaps at levels that escaped detection by EGF ligation. We find EGFR significantly contributed to signal transduction in platelets stimulated by diverse soluble agonists, augmented homotypic aggregation, and enhanced rapid thrombosis in damaged carotid arteries in intact animals. Notably, the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib reduces platelet function in cancer patients (73) and the only receptor tyrosine kinase among its targets expressed by platelets is EGFR. Tyrosine phosphorylation is a central component of signal transduction in stimulated platelets, which generally reflects the activity of soluble Src family kinases (74, 75). However, platelets additionally express membrane-associated receptor tyrosine kinases, including Eph receptors (76, 77), insulin growth factor receptor (78), VEGF receptors (79), and the Met receptor for hepatocyte growth factor (80). This list is now expanded to include EGFR that responds to EGF, TNFα, ampiregulin, and epiregulin (81) that activate EGFR homodimers in the absence of Her2 or Her4 family member heterodimers (82, 83). The extent and nature of signal transduction activated in response to EGFR ligation differ depending on the concentration of the inciting ligand as well as its identity (84–86), so EGF signaling in platelets will not recapitulate signaling in cells with a larger complement EGFR family members. In contrast to previously known platelet receptor tyrosine kinases that respond only to their cognate ligand, endogenous EGFR transactivation significantly contributed to both signaling and platelet activation in response to either GPCR and non-GPRC agonists. In support, the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor afitinib has now been determined to reduce murine platelet activation by thrombin and particularly C reactive protein (87).

Numerous members of the GPCR family transactivate EGFR (53, 54, 88–90), that is stimulation of EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation by non-tyrosine kinase receptors, to participate in the serine/threonine signaling cascades initiated by these GPCRs (53, 55). We found the tyrosine kinase activity of stimulated EGFR aided phosphorylation of platelet AKT Ser473, potentially an action of mTORC2, but that EGFR activity also was necessary for Thr308 phosphorylation that is a PDK1 target (91). The complete loss of thrombin- or PAF-induced Thr308 phosphorylation after inhibition of EGFR tyrosine kinase activity shows that AKT phosphorylation is not a direct outcome of signaling by the PAR-1 thrombin receptor nor the PtAFR receptor for PAF, so EGFR circumvention of direct downstream signaling by GPCRs occurs in platelets as well as in smooth muscle cells (55).

EGFR transactivation by GPCRs in nucleated cells requires stimulated activation of an unidentified matrix metalloproteinase to solubilize the distinct gene product pro-heparin-binding EGF (HB-EBF) (92). Quantitative analysis of the platelet proteome shows platelets do not express pro-HB-EGF (45), nor is HB-EGF present in the proteins released from stimulated platelets (1, 2). Instead, we propose the stimulated release of HMW-EGF is the functional counterpart of HB-EGF solubilization in nucleated cells that then allows autocrine EGFR tyrosine kinase activity to contribute to GPCR and collagen receptor signaling in platelets. Rapid activation of platelet aggregation by thrombin, ADP, Platelet-activating Factor, and collagen was augmented by EGFR kinase activity, so sufficient EGFR ligand was rapidly generated in response to these agonists to contribute to rapid platelet activation.

EGFR signaling in isolation did not produce either a “strong” response like thrombin, or a typical “weak” response to other GPCR ligands like PAF since EGF did not stimulate homotypic aggregation of stirred, washed human platelets (not shown). The exception to this was the clearing of platelets in quartz cuvettes by adhesion to the cuvette walls and stir bar or to coated glass slides, suggesting contributions to activation by interaction with glass or quartz surfaces to EGF stimulation since aggregation tubes are coated to reduce cellular interaction. Augmentation of a primary stimulus also was apparent in vivo where early formation of unstable platelet aggregates at the site of FeCl3 damage to the coronary vessel in mice pre-injected with EGF could not be sustained as the clot matured to a stable, occlusive thrombus.

Nearly all (80-90%) oral squamous cell carcinomas over-express EGFR, which correlates to poorer prognosis and radiation resistance (34). EGF endows OSCC cells with cancer stem-like properties (93) and a migratory phenotype (94) through an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (71). Oral cancer cells themselves did not themselves release EGF, and western blotting for phospho-EGFR showed these cells did not contain constitutively activated EGFR, so the tumor microenvironment must provide ligand(s) to stimulate tumor cell EGFR. Oral cancers are marked by an extensive immune cell infiltration (36) and the number of blood-borne platelets associate with oral cancer progression and survival (37). We identified activated platelets distributed throughout OSCC tumors and found that activated platelets physically bound OSCC cells. We found that activated platelets released soluble HMW-EGF, and continued to do so for hours after stimulation, suggesting platelets as a source of EGF bioactivity in tumors as in plasma (4, 7–9). The form of EGF released from activated platelets is far larger than fully processed 5.6 kDa EGF, but the single EGF domain in pro-EGF forms the carboxyl terminal of high molecular weight-EGF and platelet-derived HMW-EGF is an active EGFR ligand (10). Potentially, HMW-EGF at ~130 kDa would be cleared less quickly than fully processed EGF. Accordingly, we found platelet-derived HMW-EGF induced an invasive and migratory phenotype associated with markers of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition of OSCC cell lines. A notable aspect of OSCC cell migration and invasion stimulated by material released from activated platelets was that EGFR inhibition abolished all migratory, invasive, and epithelial mesenchymal transition related gene expression responses. Thus, among the hundreds of proteins, growth factors, mediators, and small molecules (1, 2) released by stimulated platelets, only HMW-EGF initiated epithelial to mesenchymal transition, migration and chemotaxis, and invasion. Indeed, only OSCC EGFR and not its receptor family members, was stimulated by platelet derived materials. Platelet-derived HMW-EGF, then, is an autocrine platelet agonist positioned by tumor infiltrating platelets (29) to contribute to OSCC tumor stem cell proliferation, tumorigenesis, and metastasis (32, 33, 93) through a novel intercellular HMW-EGF/EGFR axis aided by HMW-EGF autocrine platelet stimulation.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the aid of Dr. J. Drazba and the digital imaging core for aid in performing Cellix flow chamber experiments as well as the Flow Cytometry and Media Preparation core facilities. We also thank our many blood donors.

Abbreviations

- EGF

Epidermal Growth factor

- EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HMW-EGF

High molecular weight EGF

- IL-1β

Interleukin 1 beta

- OSCC

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- PAF

Platelet-activating Factor

- PAR1

protease-activated receptor-1

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.van Holten TC, Bleijerveld OB, Wijten P, de Groot PG, Heck AJ, Barendrecht AD, Merkx TH, Scholten A, Roest M. Quantitative proteomics analysis reveals similar release profiles following specific PAR-1 or PAR-4 stimulation of platelets. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:140–146. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wijten P, van Holten T, Woo LL, Bleijerveld OB, Roest M, Heck AJ, Scholten A. High precision platelet releasate definition by quantitative reversed protein profiling–brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:1635–1638. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semple JW, Italiano JE, Jr, Freedman J. Platelets and the immune continuum. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:264–274. doi: 10.1038/nri2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oka Y, Orth DN. Human plasma epidermal growth factor/beta-urogastrone is associated with blood platelets. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:249–259. doi: 10.1172/JCI110964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su CY, Kuo YP, Nieh HL, Tseng YH, Burnouf T. Quantitative assessment of the kinetics of growth factors release from platelet gel. Transfusion (Paris) 2008;48:2414–2420. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durante C, Agostini F, Abbruzzese L, R TT, Zanolin S, Suine C, Mazzucato M. Growth factor release from platelet concentrates: analytic quantification and characterization for clinical applications. Vox Sang. 2013;105:129–136. doi: 10.1111/vox.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pesonen K, Viinikka L, Myllyla G, Kiuru J, Perheentupa J. Characterization of material with epidermal growth factor immunoreactivity in human serum and platelets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;68:486–491. doi: 10.1210/jcem-68-2-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aybay C, Karakus R, Yucel A. Characterization of human epidermal growth factor in human serum and urine under native conditions. Cytokine. 2006;35:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joh T, Itoh M, Katsumi K, Yokoyama Y, Takeuchi T, Kato T, Wada Y, Tanaka R. Physiological concentrations of human epidermal growth factor in biological fluids: use of a sensitive enzyme immunoassay. Clin Chim Acta. 1986;158:81–90. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(86)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen R, Jin G, McIntyre TM. The soluble protease ADAMDEC1 released from activated platelets hydrolyzes platelet membrane pro-EGF to active high molecular weight EGF. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:10112–10122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.771642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor JM, Cohen S, Mitchell WM. Epidermal growth factor: high and low molecular weight forms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970;67:164–171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.1.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang DL, Lev-Ran A, Yen CF, Sniecinski I. Release of different fractions of epidermal growth factor from human platelets in vitro: preferential release of 140 kDa fraction. Regul Pept. 1992;37:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(92)90658-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dammacco F, Vacca A, Procaccio P, Ria R, Marech I, Racanelli V. Cancer-related coagulopathy (Trousseau’s syndrome): review of the literature and experience of a single center of internal medicine. Clin Exp Med. 2013;13:85–97. doi: 10.1007/s10238-013-0230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bambace NM, Holmes CE. The platelet contribution to cancer progression. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:237–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buergy D, Wenz F, Groden C, Brockmann MA. Tumor-platelet interaction in solid tumors. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2747–2760. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gay LJ, Felding-Habermann B. Contribution of platelets to tumour metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:123–134. doi: 10.1038/nrc3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasic GJ, Gasic TB, Stewart CC. Antimetastatic effects associated with platelet reduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1968;61:46–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.61.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasic GJ, Gasic TB, Galanti N, Johnson T, Murphy S. Platelet-tumor-cell interactions in mice. The role of platelets in the spread of malignant disease. Int J Cancer. 1973;11:704–718. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910110322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erpenbeck L, Schon MP. Deadly allies: the fatal interplay between platelets and metastasizing cancer cells. Blood. 2010;115:3427–3436. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-247296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stegner D, Dutting S, Nieswandt B. Mechanistic explanation for platelet contribution to cancer metastasis. Thromb Res. 2014;133(Suppl 2):S149–157. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(14)50025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabrkhany S, Griffioen AW, Oude Egbrink MG. The role of blood platelets in tumor angiogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1815:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valone FH, Austen KF, Goetzl EJ. Modulation of the random migration of human platelets. J Clin Invest. 1974;54:1100–1106. doi: 10.1172/JCI107854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt EM, Kraemer BF, Borst O, Munzer P, Schonberger T, Schmidt C, Leibrock C, Towhid ST, Seizer P, Kuhl D, Stournaras C, Lindemann S, Gawaz M, Lang F. SGK1 sensitivity of platelet migration. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30:259–268. doi: 10.1159/000339062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czapiga M, Gao JL, Kirk A, Lekstrom-Himes J. Human platelets exhibit chemotaxis using functional N-formyl peptide receptors. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng D, Nagy JA, Hipp J, Dvorak HF, Dvorak AM. Vesiculo-vacuolar organelles and the regulation of venule permeability to macromolecules by vascular permeability factor, histamine, and serotonin. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1981–1986. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraemer BF, Borst O, Gehring EM, Schoenberger T, Urban B, Ninci E, Seizer P, Schmidt C, Bigalke B, Koch M, Martinovic I, Daub K, Merz T, Schwanitz L, Stellos K, Fiesel F, Schaller M, Lang F, Gawaz M, Lindemann S. PI3 kinase-dependent stimulation of platelet migration by stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:1277–1288. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng D, Nagy JA, Dvorak HF, Dvorak AM. Ultrastructural studies define soluble macromolecular, particulate, and cellular transendothelial cell pathways in venules, lymphatic vessels, and tumor-associated microvessels in man and animals. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;57:289–326. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng D, Nagy JA, Pyne K, Dvorak HF, Dvorak AM. Platelets exit venules by a transcellular pathway at sites of F-met peptide-induced acute inflammation in guinea pigs. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1998;116:188–195. doi: 10.1159/000023944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haemmerle M, Taylor ML, Gutschner T, Pradeep S, Cho MS, Sheng J, Lyons YM, Nagaraja AS, Dood RL, Wen Y, Mangala LS, Hansen JM, Rupaimoole R, Gharpure KM, Rodriguez-Aguayo C, Yim SY, Lee JS, Ivan C, Hu W, Lopez-Berestein G, Wong ST, Karlan BY, Levine DA, Liu J, Afshar-Kharghan V, Sood AK. Platelets reduce anoikis and promote metastasis by activating YAP1 signaling. Nat Commun. 2017;8:310. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00411-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jou A, Hess J. Epidemiology and Molecular Biology of Head and Neck Cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 2017;40:328–332. doi: 10.1159/000477127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alorabi M, Shonka NA, Ganti AK. EGFR monoclonal antibodies in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: What is their current role? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;99:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leong HS, Chong FT, Sew PH, Lau DP, Wong BH, Teh BT, Tan DS, Iyer NG. Targeting cancer stem cell plasticity through modulation of epidermal growth factor and insulin-like growth factor receptor signaling in head and neck squamous cell cancer. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3:1055–1065. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharafinski ME, Ferris RL, Ferrone S, Grandis JR. Epidermal growth factor receptor targeted therapy of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2010;32:1412–1421. doi: 10.1002/hed.21365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliveira LR, Ribeiro-Silva A. Prognostic significance of immunohistochemical biomarkers in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell GI, Fong NM, Stempien MM, Wormsted MA, Caput D, Ku LL, Urdea MS, Rall LB, Sanchez-Pescador R. Human epidermal growth factor precursor: cDNA sequence, expression in vitro and gene organization. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:8427–8446. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.21.8427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawant S, Gokulan R, Dongre H, Vaidya M, Chaukar D, Prabhash K, Ingle A, Joshi S, Dange P, Joshi S, Singh AK, Makani V, Sharma S, Jeyaram A, Kane S, D’Cruz A. Prognostic role of Oct4, CD44 and c-Myc in radio-chemo-resistant oral cancer patients and their tumourigenic potential in immunodeficient mice. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20:43–56. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu CC, Chang KW, Chou FC, Cheng CY, Liu CJ. Association of pretreatment thrombocytosis with disease progression and survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rupniak HT, Rowlatt C, Lane EB, Steele JG, Trejdosiewicz LK, Laskiewicz B, Povey S, Hill BT. Characteristics of four new human cell lines derived from squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:621–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DasGupta T, Nweze EI, Yue H, Wang L, Jin J, Ghosh SK, Kawsar HI, Zender C, Androphy EJ, Weinberg A, McCormick TS, Jin G. Human papillomavirus oncogenic E6 protein regulates human beta-defensin 3 (hBD3) expression via the tumor suppressor protein p53. Oncotarget. 2016;7:27430–27444. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown GT, McIntyre TM. Lipopolysaccharide signaling without a nucleus: kinase cascades stimulate platelet shedding of proinflammatory IL-1beta-rich microparticles. J Immunol. 2011;186:5489–5496. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta N, Li W, McIntyre TM. Deubiquitinases Modulate Platelet Proteome Ubiquitination, Aggregation, and Thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2657–2666. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li W, Febbraio M, Reddy SP, Yu DY, Yamamoto M, Silverstein RL. CD36 participates in a signaling pathway that regulates ROS formation in murine VSMCs. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3996–4006. doi: 10.1172/JCI42823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W, McIntyre TM, Silverstein RL. Ferric chloride-induced murine carotid arterial injury: A model of redoxpathology. Redox Biology. 2013;1:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawsar HI, Weinberg A, Hirsch SA, Venizelos A, Howell S, Jiang B, Jin G. Overexpression of human beta-defensin-3 in oral dysplasia: potential role in macrophage trafficking. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:696–702. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burkhart JM, Vaudel M, Gambaryan S, Radau S, Walter U, Martens L, Geiger J, Sickmann A, Zahedi RP. The first comprehensive and quantitative analysis of human platelet protein composition allows the comparative analysis of structural and functional pathways. Blood. 2012;120:e73–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-416594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levitzki A. Tyrphostins: tyrosine kinase blockers as novel antiproliferative agents and dissectors of signal transduction. FASEB J. 1992;6:3275–3282. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.14.1426765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo L, Kozlosky CJ, Ericsson LH, Daniel TO, Cerretti DP, Johnson RS. Studies of ligand-induced site-specific phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:1022–1031. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00206-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J, Ferguson KM. The EGFR family: not so prototypical receptor tyrosine kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6:a020768. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bryant JA, Finn RS, Slamon DJ, Cloughesy TF, Charles AC. EGF activates intracellular and intercellular calcium signaling by distinct pathways in tumor cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:1243–1249. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.12.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Magni M, Meldolesi J, Pandiella A. Ionic events induced by epidermal growth factor. Evidence that hyperpolarization and stimulated cation influx play a role in the stimulation of cell growth. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6329–6335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varga-Szabo D, Braun A, Nieswandt B. Calcium signaling in platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1057–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown GT, Narayanan P, Li W, Silverstein RL, McIntyre TM. Lipopolysaccharide Stimulates Platelets through an IL-1β Autocrine Loop. J Immunol. 2013;191:5196–5203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z. Transactivation of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor by G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Recent Progress, Challenges and Future Research. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:95. doi: 10.3390/ijms17010095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Daub H, Weiss FU, Wallasch C, Ullrich A. Role of transactivation of the EGF receptor in signalling by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 1996;379:557–560. doi: 10.1038/379557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Little PJ. GPCR responses in vascular smooth muscle can occur predominantly through dual transactivation of kinase receptors and not classical Galphaq protein signalling pathways. Life Sci. 2013;92:951–956. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Little PJ, Hollenberg MD, Kamato D, Thomas W, Chen J, Wang T, Zheng W, Osman N. Integrating the GPCR transactivation-dependent and biased signalling paradigms in the context of PAR-1 signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:2992–3000. doi: 10.1111/bph.13398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kanda Y, Mizuno K, Kuroki Y, Watanabe Y. Thrombin-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation is mediated by epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:1657–1664. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arachiche A, Mumaw MM, de la Fuente M, Nieman MT. Protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1) and PAR4 heterodimers are required for PAR1-enhanced cleavage of PAR4 by alpha-thrombin. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:32553–32562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.472373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Esposito CL, Passaro D, Longobardo I, Condorelli G, Marotta P, Affuso A, de Franciscis V, Cerchia L. A neutralizing RNA aptamer against EGFR causes selective apoptotic cell death. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fredriksson R, Lagerstrom MC, Lundin LG, Schioth HB. The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups, and fingerprints. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1256–1272. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, Stafforini DM, McIntyre TM. Platelet-activating factor and related lipid mediators. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:419–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Manganaro D, Consonni A, Guidetti GF, Canobbio I, Visconte C, Kim S, Okigaki M, Falasca M, Hirsch E, Kunapuli SP, Torti M. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase beta by the platelet collagen receptors integrin alpha2beta1 and GPVI: The role of Pyk2 and c-Cbl. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853:1879–1888. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stalker TJ, Newman DK, Ma P, Wannemacher KM, Brass LF. Platelet signaling. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012:59–85. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-29423-5_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kanojia D, Vaidya MM. 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide induced experimental oral carcinogenesis. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Denis MM, Tolley ND, Bunting M, Schwertz H, Jiang H, Lindemann S, Yost CC, Rubner FJ, Albertine KH, Swoboda KJ, Fratto CM, Tolley E, Kraiss LW, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Weyrich AS. Escaping the nuclear confines: signal-dependent pre-mRNA splicing in anucleate platelets. Cell. 2005;122:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lindemann S, Tolley ND, Dixon DA, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, Weyrich AS. Activated platelets mediate inflammatory signaling by regulated interleukin 1beta synthesis. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:485–490. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weyrich AS, Dixon DA, Pabla R, Elstad MR, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Signal-dependent translation of a regulatory protein, Bcl-3, in activated human platelets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5556–5561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weyrich AS, Denis MM, Schwertz H, Tolley ND, Foulks J, Spencer E, Kraiss LW, Albertine KH, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA. mTOR-dependent synthesis of Bcl-3 controls the retraction of fibrin clots by activated human platelets. Blood. 2007;109:1975–1983. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-042192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pabla R, Weyrich AS, Dixon DA, Bray PF, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Integrin-dependent control of translation: engagement of integrin alphaIIbbeta3 regulates synthesis of proteins in activated human platelets. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:175–184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rall LB, Scott J, Bell GI, Crawford RJ, Penschow JD, Niall HD, Coghlan JP. Mouse prepro-epidermal growth factor synthesis by the kidney and other tissues. Nature. 1985;313:228–231. doi: 10.1038/313228a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu Q, Zhang Q, Ishida Y, Hajjar S, Tang X, Shi H, Dang CV, Le AD. EGF induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem-like cell properties in human oral cancer cells via promoting Warburg effect. Oncotarget. 2017;8:9557–9571. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ben-Ezra J, Sheibani K, Hwang DL, Lev-Ran A. Megakaryocyte synthesis is the source of epidermal growth factor in human platelets. Am J Pathol. 1990;137:755–759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sabrkhany S, Griffioen AW, Pineda S, Sanders L, Mattheij N, van Geffen JP, Aarts MJ, Heemskerk JW, Oude Egbrink MG, Kuijpers MJ. Sunitinib uptake inhibits platelet function in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2016;66:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Senis YA, Mazharian A, Mori J. Src family kinases: at the forefront of platelet activation. Blood. 2014;124:2013–2024. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-453134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Z, Delaney MK, O’Brien KA, Du X. Signaling during platelet adhesion and activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2341–2349. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prevost N, Woulfe D, Tanaka T, Brass LF. Interactions between Eph kinases and ephrins provide a mechanism to support platelet aggregation once cell-to-cell contact has occurred. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9219–9224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142053899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vaiyapuri S, Sage T, Rana RH, Schenk MP, Ali MS, Unsworth AJ, Jones CI, Stainer AR, Kriek N, Moraes LA, Gibbins JM. EphB2 regulates contact-dependent and contact-independent signaling to control platelet function. Blood. 2015;125:720–730. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-585083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blair TA, Moore SF, Williams CM, Poole AW, Vanhaesebroeck B, Hers I. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases p110alpha and p110beta have differential roles in insulin-like growth factor-1-mediated Akt phosphorylation and platelet priming. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1681–1688. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Selheim F, Holmsen H, Vassbotn FS. Identification of functional VEGF receptors on human platelets. FEBS Lett. 2002;512:107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pietrapiana D, Sala M, Prat M, Sinigaglia F. Met identification on human platelets: role of hepatocyte growth factor in the modulation of platelet activation. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4550–4554. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harris RC, Chung E, Coffey RJ. EGF receptor ligands. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:2–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dreux AC, Lamb DJ, Modjtahedi H, Ferns GA. The epidermal growth factor receptors and their family of ligands: their putative role in atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:38–53. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bazley LA, Gullick WJ. The epidermal growth factor receptor family. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(Suppl 1):S17–27. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roepstorff K, Grandal MV, Henriksen L, Knudsen SL, Lerdrup M, Grovdal L, Willumsen BM, van Deurs B. Differential effects of EGFR ligands on endocytic sorting of the receptor. Traffic. 2009;10:1115–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ronan T, Macdonald-Obermann JL, Huelsmann L, Bessman NJ, Naegle KM, Pike LJ. Different Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Agonists Produce Unique Signatures for the Recruitment of Downstream Signaling Proteins. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:5528–5540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.710087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Francavilla C, Papetti M, Rigbolt KT, Pedersen AK, Sigurdsson JO, Cazzamali G, Karemore G, Blagoev B, Olsen JV. Multilayered proteomics reveals molecular switches dictating ligand-dependent EGFR trafficking. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:608–618. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cao H, Bhuyan AAM, Umbach AT, Bissinger R, Gawaz M, Lang F. Inhibitory Effect of Afatinib on Platelet Activation and Apoptosis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43:2264–2276. doi: 10.1159/000484377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Delcourt N, Bockaert J, Marin P. GPCR-jacking: from a new route in RTK signalling to a new concept in GPCR activation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:602–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zwick E, Hackel PO, Prenzel N, Ullrich A. The EGF receptor as central transducer of heterologous signalling systems. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:408–412. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01373-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liebmann C. EGF receptor activation by GPCRs: an universal pathway reveals different versions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;331:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Prenzel N, Zwick E, Daub H, Leserer M, Abraham R, Wallasch C, Ullrich A. EGF receptor transactivation by G-protein-coupled receptors requires metalloproteinase cleavage of proHB-EGF. Nature. 1999;402:884–888. doi: 10.1038/47260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang Z, Dong Z, Lauxen IS, Filho MS, Nor JE. Endothelial cell-secreted EGF induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition and endows head and neck cancer cells with stem-like phenotype. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2869–2881. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ohnishi Y, Lieger O, Attygalla M, Iizuka T, Kakudo K. Effects of epidermal growth factor on the invasion activity of the oral cancer cell lines HSC3 and SAS. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:1155–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]