Abstract

Human vocal folds possess outstanding abilities to endure large, reversible deformations and to vibrate up to more than thousand cycles per second. This unique performance mainly results from their complex specific 3D and multiscale structure, which is very difficult to investigate experimentally and still presents challenges using either confocal microscopy, MRI or X-ray microtomography in absorption mode. To circumvent these difficulties, we used high-resolution synchrotron X-ray microtomography with phase retrieval and report the first ex vivo 3D images of human vocal-fold tissues at multiple scales. Various relevant descriptors of structure were extracted from the images: geometry of vocal folds at rest or in a stretched phonatory-like position, shape and size of their layered fibrous architectures, orientation, shape and size of the muscle fibres as well as the set of collagen and elastin fibre bundles constituting these layers. The developed methodology opens a promising insight into voice biomechanics, which will allow further assessment of the micromechanics of the vocal folds and their vibratory properties. This will then provide valuable guidelines for the design of new mimetic biomaterials for the next generation of artificial larynges.

Introduction

Human vocal folds exhibit remarkable vibro-mechanical properties, allowing them to generate an outstanding range of sounds. These laryngeal soft tissues are in the order of 1 cm long, anteriorly and posteriorly connected to the thyroid cartilage and the two arytenoid cartilages, respectively (Fig. 1). Their self-sustained vibration is induced by pulmonary airflow and leads to phonation, i.e., the production of audible air pulse trains. This acoustic wave is filtered by the resonances of the vocal tract, the geometry of which is shaped by speech articulators (e.g., jaw, tongue, lips) to generate distinguishable voiced sounds, such as vowels and sonorous consonants. Furthermore, during this process, laryngeal intrinsic muscles drive the vocal-fold adduction and abduction, stretching, and bulging. Vocal folds behave as non-linear and coupled oscillators, able to bifurcate towards complex regimes of vibration, responding to gradual variation of control parameters1–3: geometrical ones (e.g., their distance or mean glottal width), mechanical ones (e.g., their stiffness) and aerodynamical ones (e.g., air pressure), to name a few. Their outstanding vibratory abilities are due to two major properties of the vocal-fold tissue2,4: (i) the ability to endure large reversible 3D deformations during phonation in the presence of numerous collisions and mechanical stresses5 (typically between 10–50 % stretching during a glide or intonational variations, Fig. 1(b)); (ii) the ability to vibrate with a fundamental frequency ranging from less than 50 Hz to more than 1500 Hz, which is much higher than other biological oscillators such as the heart. These properties are mainly inherited from the complex and hierarchical structure of the vocal folds and of surrounding laryngeal muscles. Adult human vocal folds are known to possess a specific lamellar structure made of several layers6–10, from superficial to deep:

A stratified squamous non-keratinised epithelium (EP, thickness ≈50–100 μm), covered by mucus and involved in the underlying tissue protection and renewal.

A loose connective tissue called lamina propria (LP, thickness ≈1–2.5 mm), made of cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) with amorphous ground substances (e.g., hyaluronic acid) and fibrous networks (e.g., collagen Type I-III and elastin, both arranged in fibre bundles of diameter ranging from 0.1 to 20 μm). The LP layer is further divided into three sublayers with distinct fibre types, densities and arrangements: the superficial one (SL), also called Reinke’s space, composed of loose fibrous components comparable to soft gelatin, the intermediate one (IL) primarily composed of elastin fibres, and the deep layer (DL) primarily composed of collagen fibres. As a whole, the LP contributes to the tissue’s “passive” biomechanical properties and to the regulation of its water content.

The inferior thyroarytenoid muscle (M) or vocalis (thickness ≈7–8 mm), innervated by the inferior laryngeal nerve and responsible for the tissue’s “active” contractile properties. The inertia and stiffness of the vocalis vary according to the degree of contraction, to reach a given phonatory position.

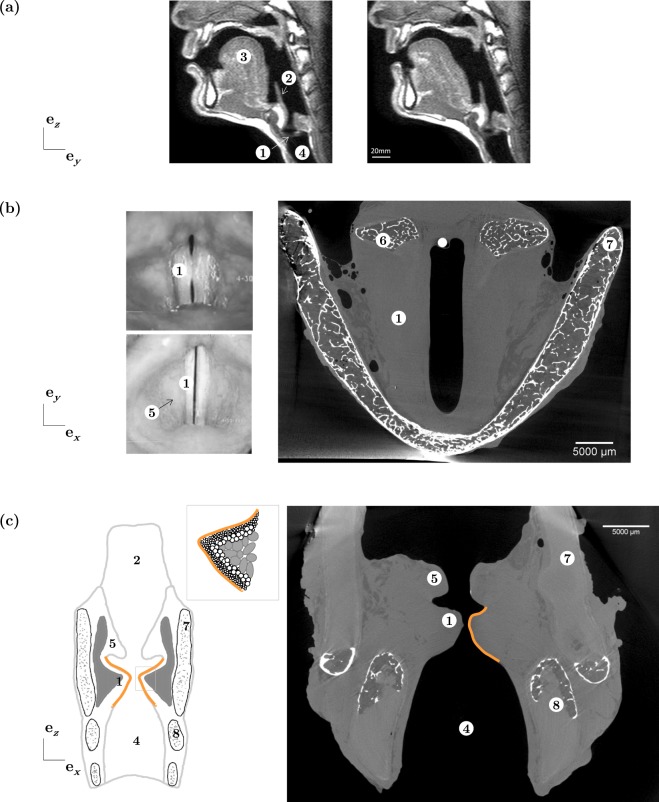

Figure 1.

Human phonatory system. (a) Mid-sagittal view of the upper airways: typical IRM images obtained during production of sounds [u] and [e] respectively (male subject, source: GIPSA-lab). (b) Transverse view of the vocal folds: (left) in vivo videolaryngoscopic images obtained during a sound-pitch variation (male subject); (right) ex vivo X-ray microtomographic image (L2, Vvox = 253 μm3). (c) Mid-coronal view of the larynx: (left) idealised scheme and zoom on the vocal-fold fibrous microstructure; (right) ex vivo X-ray tomographic image (L3, Vvox = 253 μm3). ① Vocal fold, ② Epiglottis, ③ Tongue, ④ Trachea, ⑤ Ventricular fold, ⑥ Arytenoid cartilage, ⑦ Thyroid cartilage, ⑧ Cricoid cartilage.

Current understanding of the multiscale histological features of the vocal folds is still insufficient to make the link to their vibromechanical performance. This motivates the use of full-field 3D imaging to capture these features in human vocal folds at rest or under mechanical load:

-

By contrast with other soft tissues (arteries, skin), vocal folds are not easily reachable in vivo by any medical 3D imaging technique (including ultrasound imaging), due to the surrounding laryngeal cartilages (Fig. 1(b,c)). Gold standard techniques used in clinics for the direct visualisation of their vibrations (high-speed cinematography, videostroboscopy)11 only provide partial 2D views of the vocal fold’s superior plane (Fig. 1(b)).

Recent imaging developments of major interest include optical coherence tomography which probes a tissue sample with infrared light and uses interferometric methods to detect light reflected from up to 3 mm within the tissue10,12,13. Although very promising to capture the lamellar structure of the vocal folds during in vivo vibration, this technique is severely limited for the characterisation of the several fibrous networks in the lamina propria layers and the vocalis, due to the limited spatial resolution of about 10 μm and to the strong attenuation of light beneath the lamina propria layer10,14.

-

The 3D ex vivo observation of excised vocal folds at the (sub-)micron scale remains a challenge. Various imaging techniques have been tested, such as micro Magnetic Resonance Imaging15–17, multiphoton nonlinear laser scanning microscopy (NLSM)18–21 and X-ray microtomography in standard absorption mode (see pretests in Fig. 1).

Micro Magnetic Resonance Imaging is limited by its spatial resolution (even with an ultra-high magnetic field above 7T), limiting useful voxel sizes to 403 μm3 implying that the various sublayers of the lamina propria cannot be observed15.

NLSM offers a smaller voxel size of ≈13–203 μm3, allowing observations of the lamina propria sublayers. In particular, NLSM allows the fibrous networks of elastin and collagen fibres to be distinguished without exogenous staining, by the combination of two-photon autofluorescence (TPAF) and second-harmonic generation (SHG) microscopies, respectively. However, NSLM techniques exhibit three major drawbacks: (i) The TPAF and SHG signals arising from other inherently fluorescent molecules or highly ordered structures present in the vocal folds (e.g., SHG sources in myosin filaments, TPAF sources in epithelial cells, fibroblasts, muscle cells...)21,22; (ii) The long scanning time preventing 3D in situ observation during the deformation of samples; (iii) The depth of field which is typically limited to under 150 μm with sub-cellular resolution in such highly scattering tissues. Recently, using a longer excitation wavelength which reduces scattering probability, third-harmonic generation microscopy of porcine vocal folds has allowed images up to 420 μm deep in the superficial lamina propria to be acquired, albeit with a limited contrast to distinguish collagen and elastin fibres20. Optical clearing of vocal-fold tissue using a glycerol-based reagent is also a promising approach to reduce light scattering and thus to increase imaging depth23,24.

X-ray microtomography with absorption mode and conical laboratory X-ray sources can reach sub-micron spatial resolutions (voxel size ≈3003 nm3), but suffers from two main problems: long scanning times (typically above 1 h) implying high radiation doses in the sample, and low contrast between soft biological materials (e.g., muscles, ECM fibres, epithelial cells which have similar X-ray attenuation coefficients) – see Fig. 1(c). These two problems can be overcome using synchrotron X-ray sources and facilities. Indeed, short scanning times can be reached25 (≈0.5 s per scan) with a sub-micron spatial resolution, enabling 3D in situ observations of samples during deformation. In addition, using phase retrieval imaging (PRI) modes, e.g., with the Paganin method26, highly contrasted 3D images of soft biological tissues can be acquired27–29.

Thus, following the recent studies of Vågberg et al.27 and Dudak et al.28, this work first addresses a purely technical question: (A) Does synchrotron X-ray microtomography with single phase retrieval yield sufficient contrast and spatial resolution to characterise the hierarchical structure of human vocal folds? To answer this question, 10 human larynges were scanned at various voxel sizes (≈133 down to 0.653 μm3) enabling the first ex vivo 3D images of human vocal folds to be obtained with this technique. The relevance and the limitations of this imaging technique (particularly at the smallest scales) are discussed by comparing the obtained 3D images with 2D optical micrographs of vocal folds prepared with standard histological stainings.

Despite the above limitations, the overall success in answering (A) allows quantitative 3D analysis of the layered structure of vocal folds, together with the geometries, orientation and the arrangement of muscular and ECM fibres inside the vocalis and the lamina propria. This, in turn, immediately poses a number of fundamental measurement questions in voice biomechanics:

-

(B)

What are the size and spatial variation of the aforementioned layers?

-

(C)

What is the 3D structural anisotropy of the various fibrous networks the layers are made of, as well as its spatial variation?

-

(D)

What is the morphology of muscle and ECM fibres in their network?

-

(E)

How do these 3D and multiscale descriptors evolve during a mechanical loading?

Optimisation of X-ray Imaging Conditions

Standard absorption imaging mode

A first series of scans was performed on 3 larynges (L1 to L3) using a laboratory X-ray microtomograph in standard absorption imaging mode. The spatial resolution was first set to a voxel size of 453 and 253 μm3, which is at least twice to ten times larger than the one used in standard hospital CT-scans. A priori, this resolution should allow the identification of the various layers of the vocal folds as well as a fibrous texture corresponding to muscle fibres or collagen/elastin fibre bundles. The other X-ray scanning parameters are listed in Table 1, but are similar to those already used on medical scanners for the radiology of in vivo and ex vivo larynges30,31. Typical orthogonal slices obtained with these imaging conditions are reported in Fig. 1(b,c). The external surface of the larynges is clearly identified. In addition, calcified portions of the thyroid, cricoid and arytenoid cartilages, coming from a partial ossification that starts typically at the age of 2032,33, are visible as lighter zones corresponding to higher attenuation – calcium exhibiting a much higher X-ray absorption coefficient than the other soft tissues of the larynges. Unfortunately, given that the chemical components of soft tissues exhibit similar absorption coefficients, within the vocal fold, there is insufficient contrast to separate fat tissues, non-ossified cartilages, muscles, epithelium and the inner structure of the lamina propria. This was not significantly improved while imaging the larynges with a synchrotron tomograph in absorption mode (Supplementary Fig. S1(a)), despite the use of a monochromatic beam that should improve contrast between chemically close materials. The 3D hierarchical vocal-fold structure could not be detected even with a voxel size of 133 μm3, nor even when imaging cryo-preserved samples or excised vocal folds without any surrounding cartilage (Supplementary Fig. S2(a)).

Table 1.

Scanned larynges.

| Larynx name | Donated body | Alcohol immersion | Microtomographic imaging parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age [y] | [C2H60] [%] | Vvox [μm3] | xc [mm] | U [kV] | I [μA] | n p | |

| L 1 | F | 86 | 0 | 45 3 | — | 101 | 297 | 1 440 |

| L 2 | M | 94 | 0 | 25 3 | — | 100 | 300 | 3 000 |

| L 3 | F | 82 | 0 | 25 3 | — | 100 | 300 | 3 000 |

| Larynx name | Gender | Age [y] | [C 2 H 6 0] [%] | V vox [ μ m 3 ] | x c [mm] | δ : β | E [keV] | n p |

| L4 | F | 90 | 0 | 133 | 1 200 | 1 800 | 65 | 4 902 |

| L5 | F | 85 | 0 | 133 | 1 200 | 1 800 | 65 | 4 902 |

| L6 | F | 89 | 0 | 133 | 1 200 | 1 800 | 65 | 4 902 |

| L7 | M | 81 | 0 | 133 | 1 200 | 1 100 | 65 | 4 902 |

| L8 | M | 89 | 0 | 133 | 1 200 | 1 100 | 65 | 4 902 |

| L9 | F | 75 | [0; 30; 100] | 133 | 11 000 | 1 200 | 60 | 4 900 |

| F | 92 | direct vocal-fold dissection - see Table 2 | ||||||

Italic lines refer to samples imaged with a laboratory conical X-ray source with absorption imaging mode, the others being imaged with a synchrotron source. F: female, M: male, Vvox: voxel size, xc: distance between sample and camera, U: generator voltage, I: scanning current intensity, δ:β: ratio of the dispersive and absorptive aspects of the wave-matter interaction, E: beam energy, np: number of X-ray 2D projections. †Sample only dedicated to the “high” resolution imaging of the vocal-fold structure i.e., at a voxel size of 0.653 μm3.

Phase retrieval imaging mode without contrast agent

To increase the contrast between the different constituents of the vocal folds, the samples were imaged on a synchrotron X-ray source with the objective of using phase retrieval (Paganin method), at “medium” (larynx samples) or “high” (excised vocal folds) spatial resolutions. Corresponding scanning and reconstruction parameters are reported in Tables 1 and 2. The effect of the sample-to-detector propagation distance xc on the phase contrast enhancement, with mid-field and far-field optical configurations was investigated. Some representative 3D images of the larynx and excised vocal folds obtained with this technique are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1(b–d).

Table 2.

Scanned vocal-fold samples Si extracted from larynx Lj.

| Vocal-fold sample | Microtomographic imaging parameters | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Type | Conservation | Vvox [μm3] | xc [mm] | U [kV] | I [μA] | n p | N | ||

| L 2 -S 1 | M + LP + EP | cryopreserved at −80 °C | 15 3 | — | 100 | 100 | 1 440 | 2 | ||

| L 3 -S 1 | M + LP + EP | defrosted from −20 °C | 12 3 | — | 100 | 100 | 2 496 | 2 | ||

| L 3 -S 2 | M + LP + EP | cryopreserved at −80 °C | 12 3 | — | 100 | 100 | 2 496 | 1 | ||

| Name | Type | [C 2 H 6 0] [%] | [CH 2 0] [%] | δt [min] | V vox [ μ m 3 ] | x c [mm] | δ : β | E [keV] | n p | N |

| L4-S1 | M | 30† | 0 | 5 | 0.653 | 40 | 500 | 19 | 1 995 | 1 |

| L4-S2 | M | 30 | 0 | 5 | 0.653 | 40 | 500 | 19 | 1 995 | 5 |

| L4-S3 | LP + EP | 30 | 0 | 5 | 0.653 | 40 | 500 | 19 | 1 995 | 4 |

| L6-S1 | M + LP + EP | 30 | 0 | 4 140 | 0.653 | 40 | 300 | 19 | 1 499 | 16 |

| L7-S1 | M | 0 | 10† | 650 | 0.653 | 40 | 500 | 19 | 1 995 | 1 |

| L7-S2 | LP + EP | 0 | 10‡ | 600 | 0.653 | 22 | 500 | 19 | 1 995 | 2 |

| L 10 -S 1 | M + LP + EP | 0 | 0 | — | 0.65 3 | 40–400 | 300 | 19 | 1 499 | 7 |

| L 10 -S 2 | M + LP + EP | 50 | 0 | 7 620 | 0.65 3 | 40 | 300 | 19 | 1 499 | 37 |

| L 10 -S 3 | M + LP + EP | 70 | 0 | 5 940 | 0.65 3 | 40 | 300 | 19 | 1 499 | 34 |

| L 10 -S 4 | M + LP + EP | 100 | 0 | [1; 7; 13] | 0.65 3 | 40 | 300 | 19 | 1 499 | 3 |

Italic lines refer to samples imaged with a laboratory conical X-ray source. Bold lines refer to the imaged samples used for comparison with histological measurements. Vvox: voxel size, xc: distance between sample and camera, δ:β: ratio of the dispersive and absorptive aspects of the wave-matter interaction, E: beam energy, np: number of X-ray 2D projections, N: number of scans realised on the sample. †/‡Sample kept immersed in alcohol/glue during the scan.

On the larynx at “medium” spatial resolution (hereforth defined at voxel size of 133 μm3), phase retrieval allows adipose elements to be distinguished from other soft tissues (Supplementary Fig. S1(b,c)), which is in line with results obtained with phase retrieval imaging of human breasts34. However, neither the mid-field (xc = 1.16 m) nor the far-field (xc = 11 m) configurations were sufficient to allow clear visualisation of any multi-layered arrangement or fibrous network within the vocal folds. In the mid-field configuration, some hints of texture are discernible within the vocal tissue (see arrows in zoomed view). The far-field configuration further improves contrast (revealing several vocal-fold structural features), at the cost of detrimental reconstruction artefacts at the air-tissue interface, that spread into the sample and severely alter the image (Supplementary Fig. S1(c)).

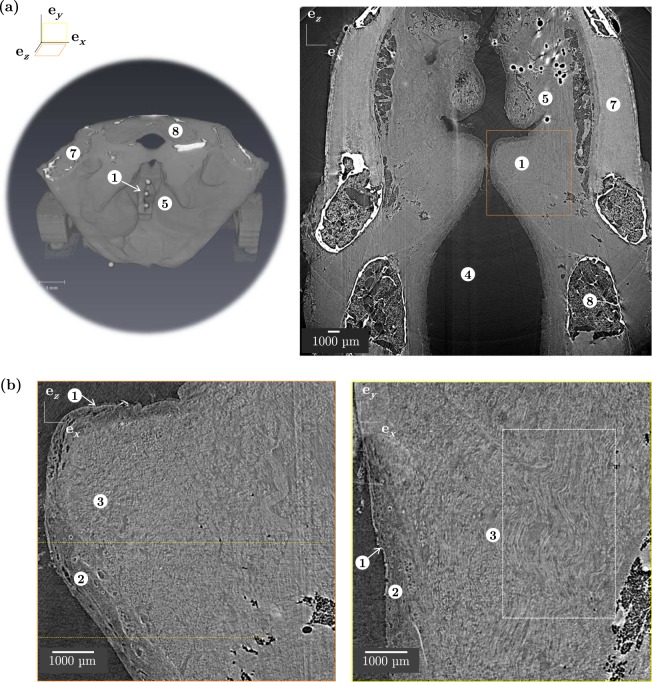

On the excised vocal fold at “high” spatial resolution (hereforth defined at voxel size of 0.653 μm3), a slight network-like texture is revealed within the muscular layer with the mid-field configuration (xc = 40 mm), as displayed in Supplementary Fig. S1(d). However, the lamina propria still appears as uniform, i.e., without any textures related to collagen and elastin fibres. Doubling the propagation distance xc to 80 mm enhances the phase contrast for the muscular layer, but also interferences at air-tissue interface. In the far-field configuration (xc = 400 mm), contrast within the vocal fold is not drastically improved and details of the texture are lost due to blur.

Phase retrieval imaging mode with contrast agents

To further increase the contrast between the constituents of soft tissues, a series of excised vocal folds were first immersed into aqueous solutions of formaldehyde or ethanol and then imaged according to similar scanning parameters as above (see Table 2). As evident from the corresponding images shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, formaldehyde reduces contrast and was therefore discarded: the muscular fibrous networks of the vocalis now appear as a fully homogeneous material. On the contrary, the use of ethanol solutions improve contrast, in agreement with the 3D images obtained in previous studies28,35,36. After a 3-day immersion in an aqueous solution with 30% of ethanol (Supplementary Fig. S2(b)), the different vocal-fold sublayers can now be identified, i.e., the vocalis with well-defined cross sections of muscle fibres, the lamina propria with a similar but finer texture, and the epithelium with some saturated brightness due to sharp phase contrast at air-tissue interface. These qualitative observations are confirmed and even reinforced for an increased concentration of ethanol, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S2(c) in case of a 4-day immersion in an aqueous solution with 70% of ethanol. As displayed in Supplementary Fig. S2(e), immersion and scanning in pure ethanol was also attempted with the objective of measuring diffusion times. A diffusion time δt of 13 min was found as a minimum to identify the vocal-fold sublayers and the fibrous texture within the lamina propria. Given the success of pure ethanol immersion combined with phase retrieval, images of the entire larynx confined in a box filled with pure ethanol were also acquired at the “medium” spatial resolution (voxel size of 133 μm3) and far-field configuration: Fig. 2 shows representative slices obtained in coronal and transverse planes. The wavy arrangement of muscular-fibre bundles and their orientation along the anteroposterior direction are clearly visible. In addition, although the fibrous texture within the lamina propria is still hardly detectable at this spatial resolution, the delineation of this layer with the vocalis can be well-differentiated (see Fig. 5(a)).

Figure 2.

Characterisation of human laryngeal tissue’s architecture using X-ray synchrotron microtomographic PRI imaging mode and medium spatial resolution (Vvox = 133 μm3). (a) left: 3D reconstruction of sample L5; right: tomographic image of a larynx vertical 2D slice, coronal plane (L9, [C2H60] = 100%). ① Vocal fold, ④ Trachea, ⑤ Ventricular fold, ⑦ Thyroid cartilage, ⑧ Cricoid cartilage. (b) Zoom on one vocal fold and its inner fibrous architecture in coronal (orange) and perpendicular transverse (yellow) planes (L9, [C2H60] = 100%). ① EP, ② LP, ③ M.

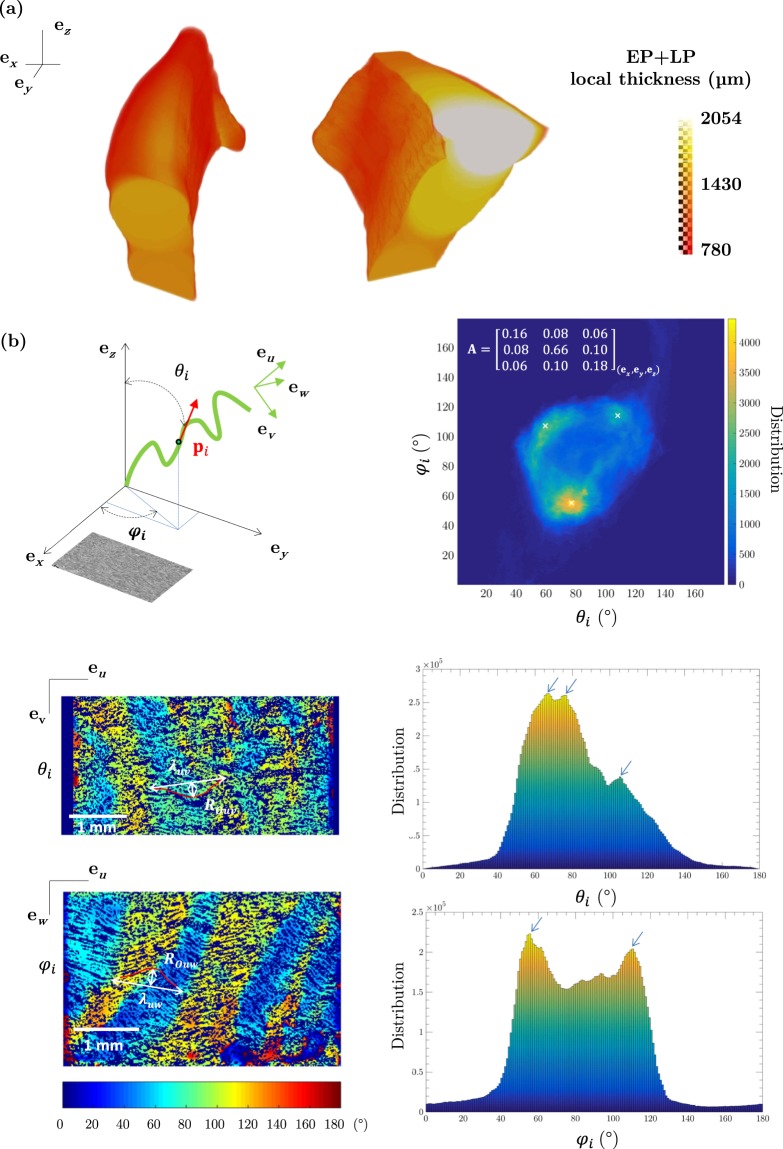

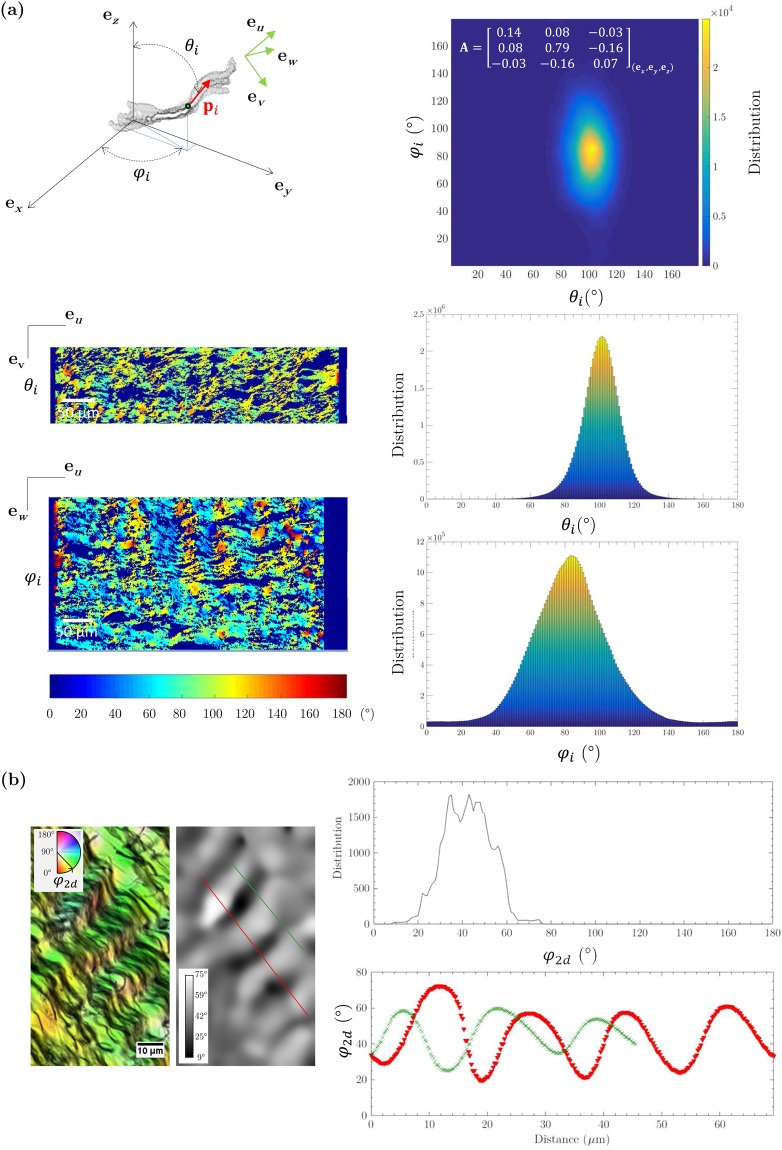

Figure 5.

Quantification of several structural descriptors of the vocal-fold EP-, LP- and M-sublayers derived from images acquired at medium spatial resolution (voxel size of 133 μm3) (L9). (a) 3D local thickness map of a EP+LP-layer subvolume. (b) 3D orientation map of the muscle fibres network in a M-layer 41.52 mm3 subvolume; corresponding 2D distribution of θi and φi values; illustration of their distribution on two orthogonal 2D slices of the subvolume.

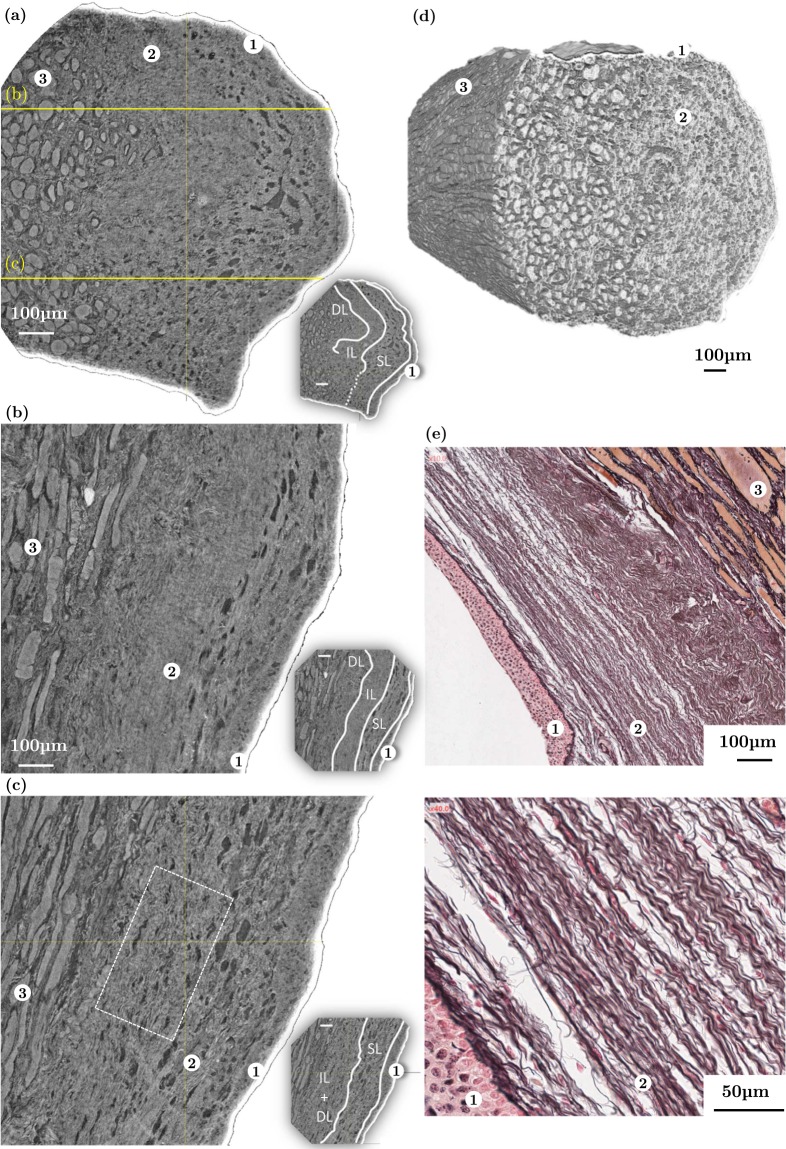

Comparison with standard histological optical micrographs

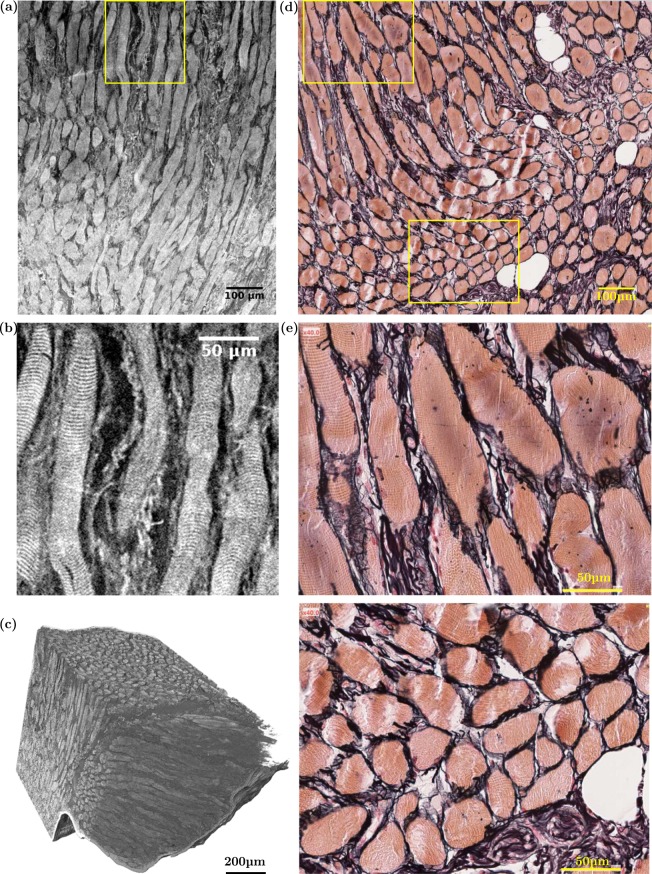

Standard histological stained samples were extracted from a vocal fold. The resulting optical micrographs were compared with slices obtained on the same larynx using high resolution synchrotron X-ray tomography with phase retrieval and ethanol immersion. This comparison is shown in Figs 3 and 4 and qualitatively validates the imaging procedure. In particular, the skeletal “muscle fibres” (also called “muscle striated cells” or “rhabdomyocytes”) are usually recognised by their distinctive transverse banding patterns due to the arrangement of myofibrils. This transverse banding is detectable with both imaging techniques (Fig. 3). As shown on both images, the muscle fibres are grouped together into bundles (or fasciculi) and surrounded by loose connective tissue. Furthermore, multiple epithelial cell layers, closely packed, stratified, and nucleated2,37, are also apparent on both X-ray images and histological micrographs, thereby allowing the epithelium delineation (Fig. 4(a–c,e)). Moreover, the tortuous arrangement of smaller fibres which are noticeable in tomographic images between the muscle fibres of the vocalis and the epithelium, is similar to the organisation of ECM fibres in the lamina propria layer, as highlighted in histological views in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S3. However, such histological micrographs show that, in the investigated regions, collagen Type I, collagen Type III, and elastin fibres in the ECM are closely entangled, which makes their distinction into separate networks difficult, as is the case in nonlinear microscopy18. Synchrotron X-ray microtomography does not solve the issue either: we were not able to distinguish elastin fibres from collagen ones, since their X-ray absorption and phase coefficients are very close. Finally, the microstructural differences between arytenoid hyaline and elastic cartilages can also be identified with both imaging techniques (Supplementary Fig. S4). In particular, the high content of elastic fibres surrounding the chondrocytes (nuclei) in lacunae is detectable in X-ray scans of elastic cartilage.

Figure 3.

Comparison between (left) synchrotron high-resolution X-ray microtomographic images (PRI mode, Vvox = 0.653 μm3) of the left vocalis fibrous network and (right) 2D histological photomicrographs of the right vocalis excised from the same larynx L10. (a) 2D coronal view of L10-S3, [C2H60] = 70%. (b) Zoom on the banding patterns of the muscle fibres located within the yellow frame in (a). (c) 3D reconstruction of L4-S2, [C2H60] = 30%. (d) 2D coronal view of L10-S5, prepared with Reticulin stain: Type III collagen fibres (black); muscular striated-cells or “fibres” (orange); adipocytes (white). (e) Zooms on the banding patterns of the muscle fibres located within the yellow frames in (d).

Figure 4.

Comparison between (a–d) synchrotron high-resolution X-ray microtomographic images (PRI mode, Vvox = 0.653 μm3) of the left lamina propria fibrous network and (e) 2D histological micrographs of the right lamina propria excised from the same larynx L10. (a) 2D coronal view of L10-S3, [C2H60] = 70%. (b,c) Companion and orthogonal 2D transversal views. (d) Corresponding 3D reconstruction; (e) (top) Histological photomicrograph of L10-S5 prepared with Reticulin stain: Type III collagen fibres (black); muscle fibres (orange); stratified squamous epithelium (pink); (bottom) Zoom on the wavy arrangement of elastin and collagen bundles of fibres. ① EP, ② LP, ③ M.

3D Hierarchical Structure of the Vocal Folds

Larynx and vocal fold geometries

Using large voxel sizes of 453 and 253 μm3, the obtained 3D images allow the definition of the outer surface of the larynx and the vocal folds (Figs 1 and 2). Using phase retrieval imaging combined with ethanol immersion, important measurements of the inner and layered structure of vocal folds can be made (see next subsections). In addition, the database of samples scanned in this work comprises four laryngeal samples (L5 to L8) scanned at rest and while being subjected to a 3D deformation resulting from cricothyroid tilt (Supplementary Figs S7 and S8). Thanks to the glass beads stuck inside the samples onto the vocal folds (see Fig. 2(a)), the longitudinal elongation λ of vocal folds after the larynx deformations can be estimated: depending on the tested samples, λ ranges from 1.05 to 1.27 with a mean value 1.13.

Structure of the vocalis

In the vicinity of the lamina propria, the vocalis is constituted of well-delimited fibres, mainly oriented along the vocal-fold longitudinal direction (Figs 2 and 3). Further from the lamina propria (typically beyond 1 mm), other fibrous networks with perpendicular orientation are also highlighted in several muscle regions (see Fig. 3(c)). They appear at the transition between the vocalis and the external part of the thyroarytenoid muscle, or between the vocalis and the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle. In addition, some interesting results were obtained on the ethanol-preserved samples at both “medium” (voxel size of 133 μm3, Fig. 5) and “high” (voxel size of 0.653 μm3, Fig. 6) spatial resolutions:

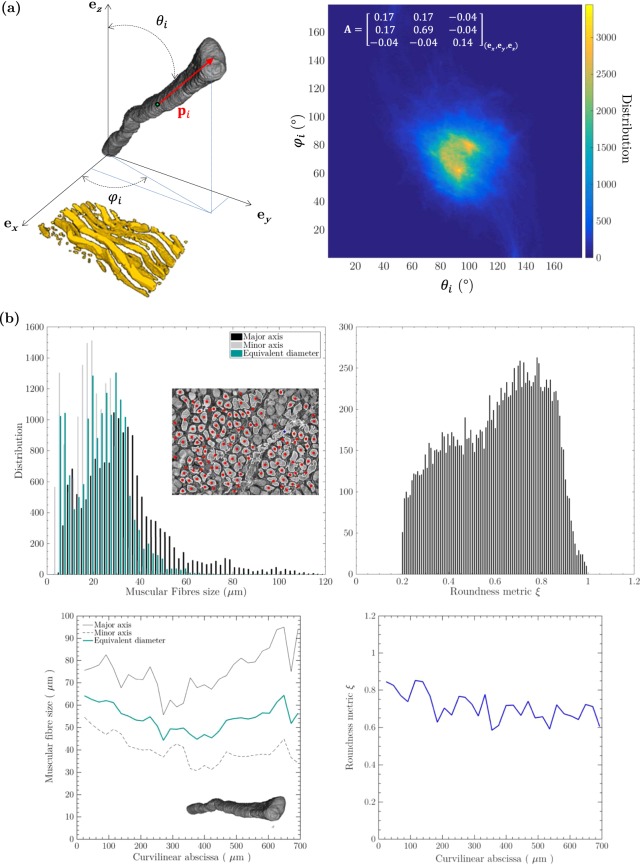

Figure 6.

Quantification of several structural descriptors of the vocal-fold muscular layer (L10-S3) derived from images acquired at high spatial resolution (voxel size of 0.653 μm3). (a) 3D orientation map of the muscle fibres network in a M-layer 0.007 mm3 subvolume. (b) Statistical dimensions and shapes of the muscular fibrous network (top panel) and that of an individual muscle fibre extracted from the 3D image (middle panel).

Medium spatial resolution

Figure 5(b) shows a 3D fibre orientation map of the muscular fibrous network in the reference frame (ex, ey, ez), where ex coincides with the mediolateral direction, ey, with the anteroposterior direction and ez, with the inferosuperior direction. The map was obtained from a subvolume of about 3.25 × 5.01 × 2.55 mm3 that was extracted near the lamina propria of larynx L9. The selected 3D region was characterised by a single network of muscle fibres mainly oriented along the longitudinal direction ey of the fold – Fig. 2(b) shows a representative slice plotted in white within the cropped subvolume. Indeed, the mean values of the angles θi and φi are both close to 82°, the non-diagonal components of the fibre orientation tensor A are very small, and its component ayy is much larger than axx and azz. However, muscle fibres are not perfectly aligned: the standard deviations for θi and φi reach non zero values, of the order of 25° and 28°, and so the components axx and azz. It is worth noting that these two components are practically equal, which means that the network of muscle fibres exhibits transverse isotropy at first order. In other words, the muscle fibres can be seen as a network with rotational symmetry with respect to the anteroposterior direction, ey. More precisely, three peaks emerge from the 3D orientation map (noted with white crosses on Fig. 5(b)): (θi, φi) = (77°, 55°); (59°, 107°); (108°, 114°). Such peaks are also highlighted once reported in cumulative histograms of θi and φi angles (noted with blue arrows). They are probably related to the 3D wavy arrangement of muscle fibres, as illustrated on representative orthogonal slices in Fig. 5(b). Please note that the variations of local φi-orientations in the (eu, ew) plane as defined in Fig. 5(b) are delimited by peaks and valleys of a quasi-sinusoidal waveform, which is a characteristic of the fibrous network waviness: the corresponding spatial period and magnitude were estimated to be around λuw = 1.50 mm ± 0.15 mm and R0uw = 220 μm ± 60 μm, respectively. In the orthogonal plane (eu, ev), a quasi-sinusoidal waveform is also observed, with a spatial period λuv = 1.51 mm ± 0.2 mm and an amplitude R0uv = 198 μm ± 60 μm.

High spatial resolution

The same (but local) analysis was carried out with a subvolume of 209 × 403 × 81 μm3 (Fig. 6(a)) extracted from sample L10-S3 at 1.3 mm from the lamina propria. The corresponding fibre orientation tensor is practically identical to that found at “medium” spatial resolution (note that the axy component reaches a non negligible value due to a slight misalignment of the microstructure with respect to the reference frame). The local fibre orientation distribution is also dispersed (see the 3D orientation map in Fig. 6(a)), with standard deviations for θi and φi equal to 24° and 28°, respectively. The whole angular distribution looks rather homogeneous and centred around a single point (θi, φi) = (93°, 76°). Yet, two peaks emerge in the 3D orientation distribution, for (θi, φi) = (93°, 61°); (100°, 80°). At this spatial resolution, the analysis is sensitive to the variation of local orientation along fibres, so that both peaks can be related to their waviness, as illustrated by the segmented fibres shown in Fig. 6(a). In addition, other descriptors of muscle fibres were extracted within a subvolume of size 615 × 450 × 98 μm3, close to the previous one. For instance, the average surface number of muscle fibres was found to be around 380 mm−2, by analysing slices perpendicular to the main fibre orientation. The equivalent diameter of muscle fibres de, the size of their minor and major inertia axes were computed: the corresponding distributions are plotted in Fig. 6(b). The peak value of de is 29.3 μm (median value 23.8 μm). The shape of fibres was quantified by a peak roundness metric ξ of 0.70 (median value 0.63), which shows that muscle fibres exhibit quasi-circular cross-sections. These results are in agreement with those obtained from a single muscle fibre of length 700 μm (Fig. 6(b)), which was isolated from the fibrous network. The mean diameter de of this fibre is 54 μm (values ranging from 44.3 to 64.3 μm) and its mean roundness metric is close to 0.71 (values ranging from 0.58 to 0.85).

Structure of the lamina propria and the epithelium

For the lamina propria and the epithelium, the following results were obtained on ethanol-preserved samples:

Medium spatial resolution

The thickness of the lamina propria together with the epithelium was measured with both 2D and 3D views. In Fig. 4, regions of tissues characterised by X-ray microtomography and histological staining were positioned in the vocal-fold membranous part, at about 2–3 mm from the vocal process (arytenoid’s anterior end). Within this vocal fold (female, 92 years), the thickness in the coronal plane was measured between 530 and 930 μm from the 3D images (mean value 750 μm ± 95 μm over 50 measurements in a 3D neighboured region), and between 430 and 650 μm from the 2D histological micrographs. The 3D local thickness maps of both vocal folds were also derived on sample L9 (Fig. 5(a)), revealing an asymmetry between each fold, where thickness values globally varied from 780 to 2054 μm depending on the anatomical location.

High spatial resolution

The set of 2D and 3D micrographs related to sample L10-S3 in the mid-membranous region38 and displayed in Fig. 4 allows an interesting inspection of the inner and multilayered structure of vocal folds in the strongest collision zone. The slice (a), which is perpendicular to the anteroposterior direction, and its two companion and orthogonal slices (b) and (c) emphasize the epithelium ①, the lamina propria ② and the vocalis ③. From them, the spatial variation of the epithelium thickness along the vocal-fold outer surface (free edge) was estimated. For this sample, the 3D measurements yielded a thickness ranging from 30 to 80 μm, which is in line with standard 2D histological assessments (see Fig. 4(e) and Supplementary Fig. S3), and previous values reported in the literature2,39,40. More interestingly, X-ray microtomographic slices (a-c) also reveal sublayers of complex shapes and characteristic textures within the lamina propria. When these sublayers can be distinctly separated, they are delineated in Fig. 4(a–c), and interpreted according to those detectable on the 2D photomicrograph (e):

Underneath the epithelium, a first sublayer is recognised (a-c, e), where the ECM fibre content is lower than in the rest of the lamina propria: it is characterised by large darker zones of ≈20 μm in size, aligned with the fibrous networks. This region corresponds to the superficial layer of the lamina propria (SL), or Reinke’s space. In the observed volumes, large variations of the SL thickness were observed, ranging between 100 and 200 μm.

Underlying the superficial sublayer, the intermediate sublayer (IL) is also detected (a-b, e), where the ECM fibre content is higher, and the fibre waviness is far less pronounced than in the third deep sublayer (DL), located between the IL and the vocalis.

The three aforementioned sublayers are clearly visible in micrographs (b, e). However, it is worth noting that this is not the case everywhere in the volume: in slices (a) and (c) for example, both IL and DL layers can hardly be separated by the naked eye.

We further analysed the fibrous structure within the so-called “vocal ligament”, which contains both intermediate and deep sublayers of the lamina propria2,41, and is considered as the primary load-bearing portion of the vocal fold, especially at high longitudinal stretches19. The 3D orientation map of the network of collagen-elastin fibres together with its corresponding fibre orientation tensor A are given in Fig. 7(a). These data were obtained from a subvolume of 267 × 515 × 131 μm3 extracted from sample L10-S3 – Fig. 4(c) shows a representative slice plotted in white within the cropped subvolume. Despite the slight misalignment of the microstructure with respect to the reference frame (ex, ey, ez), it is fair to conclude that fibre bundles are mainly oriented along the ey direction, as for muscle fibres near the lamina propria: the fibre bundle orientation distribution is centred around (θi, φi) = (102°, 85°), so that the component ayy of A is much higher than axx and azz. It is also interesting to mention that axx is twice as large as azz (the dispersion of the angular distribution is characterised by standard deviations for θi and φi equal to 12° and 25°, respectively), proving that the fibrous network of the lamina propria does not exhibit transverse isotropy but orthotropy: whereas muscle fibres exhibit transverse isotropy with respect to the anteroposterior direction, the fibre alignment along this direction and inside the lamina propria is more pronounced through the thickness of the lamina propria (within the plane (ex, ey)) than perpendicularly (within the plane (ex, ez)). In addition, as for muscle fibres, a quasi-periodic variation of the local orientation of fibres along the anteroposterior axis ey is clearly observed on 2D slices. The spatial periods and amplitudes of the fibre waviness were thus measured in orthogonal planes (eu, ew) and (eu, ev) leading to λuw = 56.3 μm ± 16 μm, R0uw = 4.6 μm ± 1.5 μm, λuv = 44.3 μm ± 15 μm and R0uv = 11.3 μm ± 3 μm. Despite being slightly higher, the 3D spatial periods are consistent with the value deduced from the 2D histological micrograph shown in Fig. 7(b), i.e., λ2D = 16 μm ± 1.6 μm. Finally, the 3D contourlines of several fibrous bundles of collagen and/or elastin were also detected, as illustrated in Fig. 7(a). Such bundles have a mean diameter and length around 50 μm and 400 μm, respectively. However, due to the limited contrast obtained in this zone (see Fig. 4), no threshold-based segmentation was successfully achieved to provide a statistical quantification of their dimensions and shape.

Figure 7.

Quantification of several structural descriptors of the vocal-fold LP-layer (L10-S3). (a) 3D orientation map of the collagen and elastin fibrous networks in a LP-layer 0.018 mm3 subvolume derived from microtomographic measurements acquired at high spatial resolution (voxel size of 0.653 μm3); corresponding 2D distribution of θi and φi values; illustration of their distribution on two orthogonal 2D slices of the subvolume. (b) In-plane waviness of Type III collagen fibres network, derived from histological measurements.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Since the reference histological findings and 3D sketches on the vocal-fold multilayered arrangement provided by Hirano et al. in the 1970-80s6,41,42, very few experimental quantitative data have been collected to characterise the complex architecture of human vocal-folds, in particular at the micrometer scale. Little information is available in the literature for the structure of vocalis at this scale. Regarding the multi-layered structure of the lamina propria and the epithelium, the existing information is mainly derived from standard 2D histological stainings8,37,40,41, micro-Magnetic Resonance Imaging techniques17 with a restrained spatial resolution, or, in a growing number of studies, from non-linear laser scanning microscopy where some relevant quantitative structural descriptors were assessed for the ECM fibres and their networks18–21. In the present work, for the first time, the 3D hierarchical architecture of human vocal folds is revealed ex vivo by means of fast synchrotron X-ray microtomography with phase retrieval imaging mode, together with the use of a suitable contrast agent. This 3D characterisation was performed at two spatial resolutions: (i) “medium” (voxel size of 133 μm3), with the visualisation of the vocal fold geometries, their general placement within the larynx and the identification of their layers, e.g., vocalis, lamina propria (and its sublayers) and epithelium; (ii) “high” (voxel size of 0.653 μm3), with a fine examination of muscular and ECM fibres as well as fibrous networks. Comparing results of the aforementioned studies with those obtained here, some answers to the technical and fundamental questions (A-E) listed in the Introduction can now be discussed:

Relevance of synchrotron X-ray microtomography

To answer question (A), a methodology was elaborated to prepare vocal-fold samples with suitable conditions of tissue conservation, and to optimise the optical settings for scanning. The 3D imaging protocol was validated by comparing 3D images with standard 2D histological micrographs. A high degree of accordance was found between both techniques from a qualitative standpoint. Quantitatively, however, some differences were found, e.g., for the thickness of the lamina propria or for the waviness of its fibres. Although small, these discrepancies may be mainly ascribed to the manipulations to which the tissue is subjected during the protocol for histological staining, e.g., pre-deformation of samples, dehydration and possible induced shrinkages, warming, paraffin-embedding, microtomy artefacts... This point undoubtedly constitutes a strength of 3D X-ray imaging. Furthermore, compared with histological staining or other advanced 3D imaging techniques such as multiphoton microscopy18–22,43, the other interesting advantage of X-ray 3D imaging is the possibility (i) to get high resolution and in depth 3D images of soft tissues (ii) with very fast scanning times (here the scans were 1–2 min long). However, the technique exhibits three main limitations that should be overcome for future observations. First, the use of ethanol was necessary in order to enhance phase contrast: its impacts on the mechanical behaviour of vocal fold tissues must be assessed before performing mechanical tests with 3D in situ observations. Note that the relatively short duration of fixation of 13 min – the minimum for the fibrous texture of the lamina propria to be observed – should limit the impact on the mechanical behaviour of the tissue. Second, we experienced difficulties in discriminating collagen fibres from elastin fibres, since both their absorption and phase coefficients are very close. A first possible solution to overcome this problem consists in selectively digesting a target protein from the vocal-fold tissue, as previously done in the case of arterial walls44. Another solution could be to use chemical markers able to track one specific fibrous protein29,45. Last, we were not able to properly analyse the morphology of individual ECM fibres: this challenging task could be achieved by further increasing the spatial resolution of the images46.

Size and spatial variation of the vocal fold (sub)layers

Regarding question (B), the thickness of the lamina propria and the epithelium is known to vary with gender and age37,41,47,48. The local 3D thickness map displayed in Fig. 5(a) demonstrates that it also varies with the anatomical location within the vocal-fold tissue, being the thickest at the midportion and becoming thinner towards the anterior and posterior ends, in agreement with previous 2D studies41. Besides, the qualitative division of the lamina propria into a superficial sublayer (SL) and a “vocal ligament” (IL + DL), as illustrated in Fig. 4(a–c), is in line with the typical distribution reported by Gray et al.37, i.e., with a SL-layer ranging between 25% to 35% of the initial depth of the lamina propria. However, even in the mid-membranous region of the vocal folds, the 3D images show that this trilamellar structure is not always observable. More precisely, we found that the intermediate sublayer (IL), which is marked by a dense network of straighter ECM fibres, may be confined to a region likely to endure the highest collision stresses during phonation38,49. This heterogeneous distribution in the vocal ligament is consistent with the structural measurements previously achieved by Klepacek et al.17 using micro-MRI and plastination methods. It also supports the hypothesis that regions exposed to higher stresses in the vocal tissues are characterised by a higher density of fibrous proteins produced to strengthen the ECM37,50.

3D structural anisotropy of fibrous networks in the lamina propria and the vocalis

Within the vocal ligament, Kelleher et al.19 estimated the 2D orientation distribution function of collagen fibres which was centred along the anteroposterior axis. We computed the corresponding 2D second-order fibre orientation tensor:

| 1 |

the components of which are very close to those we obtained in (ex, ey) for the 3D fibre orientation tensor reported in Fig. 7(a). Thanks to the 3D images, it is now possible to extract 3D properties of the fibre orientation in the vocal, and thereby to answer question (C): at the first order, it neither exhibits a 2D layered symmetry, nor transverse isotropy, but orthotropy with a pronounced major orientation along the anteroposterior direction, and minor and intermediate orientations along the inferosuperior and mediolateral directions, respectively. It is worth noting that this result does not fit with the 3D schematic fibrous arrangement proposed by Madruga de Melo et al.8 for the lamina propria: the fibrous architecture these authors suggested exhibits orthotropy without any privileged direction, while it is clearly highlighted here along the anteroposterior direction. This information is also important to build relevant micromechanical models for the lamina propria19,47,50,51, that are able to accurately reproduce the biomechanical properties of vocal tissues in multiple directions close to those encountered in vivo. For example, Kelleher et al.19,50 showed that both the degree and the magnitude of the vocal ligament anisotropy strongly impact the predictions of its fundamental frequency of vibration. Also, new information was obtained regarding the structural anisotropy of muscle fibres in the vocalis. The resulting 3D fibre orientation distributions demonstrate that muscle fibres are mainly aligned along the anteroposterior axis, with a transverse isotropy texture. Here again, this information is important to fully characterise and model the mechanics of the vocalis under realistic physiological loadings52,53. In particular, Böl et al.53 showed that such an anisotropic property implies different stress responses of the tissue under the applied compression modes, which is critical for the better understanding of vocal-fold collision.

Morphology of ECM and muscle fibres

Regarding question (D), Miri et al.18 quantified the wavy shape of collagen fibres from three lamina propria (65 year-old female larynx, 55- and 68-year-old male larynges). The average period λ0 was found to be around 35 μm (values ranging from 18 to 48 μm), while the average amplitude R0 was found to be equal to 6 μm (values ranging from 2.6 to 8.4 μm). The waviness parameters we estimated from X-ray microtomographic images are consistent with the aforementioned values, although lying in the highest range. Furthermore, regarding muscle fibres in the vocalis, prior works in the 1980s reported a typical equivalent diameter of 32 μm for (white) fast-twitch fibres and 28 μm for (red) slow-twitch fibres, based on 2D microscopic differentiation54. This is in line with the equivalent circular diameter found in the present study at the scale of the 3D network. These structural data are very helpful to understand and model the mechanics of vocal folds.

Towards mechanical tests with 3Din situobservations

At “medium” spatial resolution, a preliminary collection of 3D images was acquired for larynges subjected to anatomical placements close to those occurring during a typical phonatory cycle. This constitutes an important database which can be used either to study the larynx and vocal fold anatomy31,55 or to simulate the mechanics of vocal folds56,57. For example, the vocal fold elongation λ which was measured after the laryngeal tilt is consistent with the recent measurements obtained by Lagier et al.55. Using 10 excised human larynges prepared and deformed in close conditions (body ages from 71 to 92, freezing in 0.9% saline, double adduction), these authors reported λ-values ranging from 1.05 to 1.28 (mean value 1.12). Finally, with a scan duration of 1–2 min, it is worth mentioning that the adopted methodology is very promising to further track, at “high” spatial resolution, the deformation and the rearrangement of muscle and ECM fibres during mechanical load, thereby answering question (E). Such information is crucial to gain an in-depth understanding of the link between the micromechanics of vocal-fold tissues and their unique vibratory performances. Although left static in the present study, a part of the scanned samples were clamped inside a micropress mounted in the imaging set-up, proving the feasibility of future in situ tension-compression tests.

Methods

Samples preparation

The experiments were carried out with 10 ex vivo and healthy human larynges, referred to as Li, i ∈ [1, …, 10]. Samples details are given in Table 1. Anatomical pieces were excised from donated bodies within 48 h post-mortem at the Laboratory of Anatomy of the French Alps (LADAF - UGA, Grenoble Hospital Univ.). All but one larynx (fresh larynx L10) were preserved by freezing (−20 °C) up to X-ray scanning protocol and after. Experimental protocols were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the General Directorate for Research and Innovation (DGRI - French Research Ministry) and the LADAF. All experiments were conducted as regulated by the French ethical and safety laws in the frame of Body Donation (voluntary donation, made by the donor during his lifetime, after written and informed consent), in accordance with the ESRF Safety Office for Biology and Biochemistry and 3SR Lab policy. Samples were prepared following several protocols developed for testing and improving the microstructure exploration of the vocal-fold tissue, first with entire larynges, then on dissected vocal-fold samples:

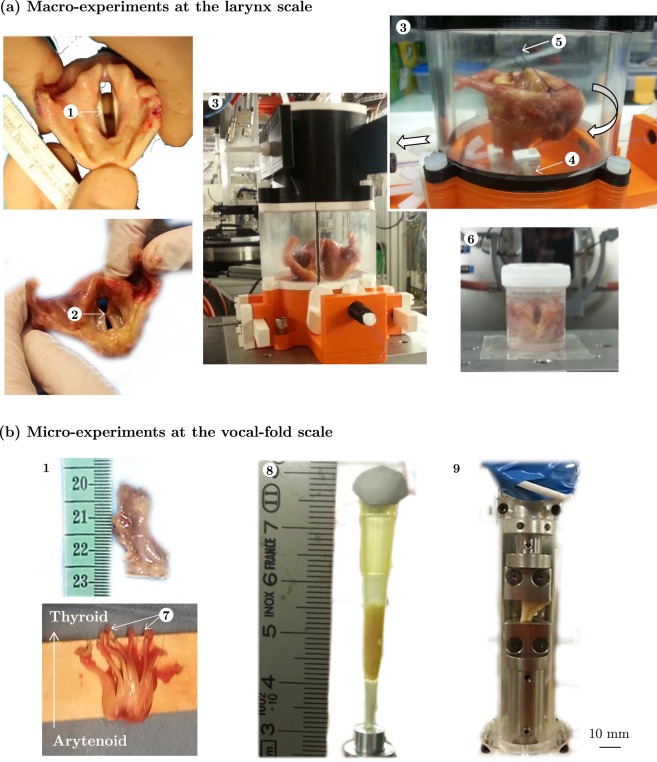

Experiments on larynges

Larynx samples L1 to L9 were used with experimental details given in Table 1. Before any manipulation, each sample was defrosted 20 min in water (T ≈ 20 °C), then placed in a confined and fully-hydrated set-up, to reproduce realistic laryngeal phonatory placement and to control vocalis muscle stretching55 (Fig. 8a). The set-up is made of 3D-printed PLA pieces and two PMMA half-cylinders forming a sealed transparent chamber (inner diameter of 8 cm, wall thickness of 5 mm). It was designed to mimic the rocking movement of the thyroid cartilage forward and backward on the cricoid cartilage, which elongates the vocal folds in vivo. Mounting a larynx in it comprised several steps: (i) a stitch was made between the vocal processes of the arytenoid cartilages using a 5/0 surgical wire (Polysorb®), so as to adduct the arytenoid cartilages and held the vocal folds close together in a phonatory-like position55 (Fig. 8(a.2)); (ii) a stiffer 3/0 surgical wire was also fixed around the cricoid cartilage anterior part, passing through the thyrocricoid membrane, and linked to a manual activator of the cartilages’ rocking motion; (iii) a wooden pike was introduced trough the thyroid cartilage and fixed into the containment device to ensure a reference static position (Fig. 8(a.4)); (iv) Glass beads (1 mm in diameter) were stuck on larynx cartilages using tissue glue (PeriAcryl®90, Surgibond®) so as to add 3D positions of reference and help to identify the laryngeal structures during X-ray data collection. Such markers also allowed to measure the vocal fold elongation during the rocking movement of the larynx; (v) the larynx was then placed into the containment device, blocking the thyroid cartilage thanks to the wooden pike and to additional wires stitched through its both ended branches (Fig. 8(a.5)); (vi) the whole device was kept opened in an airtight chamber which was regulated at proper hygrometric conditions (100% RH, achieved with a humidifier Fisher & Paykel HC150). Samples L1 to L8 were subjected to steps (i-v). For sample L9, the larynx was directly confined in a sealed box filled with a dilute aqueous solution of ethanol (Fig. 8(a.6)) the concentration of which, [C2H60], was set to 0, 30 and 100%.

Figure 8.

Experimental set-ups developed for X-ray microtomography characterisation of the vocal-fold tissues (a) within the preserved laryngeal structure and (b) once dissected. ① Vocal fold, ② Stitch between vocal processes, ③ Macro-mechanical set-up, ④ Wooden pike, ⑤ Wires blocking thyroid’s branches, ⑥ Set-up for sample L9, ⑦ Dissection procedures for samples Li-Sj, ⑧ Pilot set-up, ⑨ Micro-mechanical tension device.

Experiments on dissected vocal folds

To enable 3D imaging at micrometer-scale resolution, vocal-fold samples were dissected from six laryngeal specimens Li (i = 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 10 – see Table 2). All but one larynx (fresh larynx L10) were already exposed to X-ray radiation prior to dissection. They were cut along the anteroposterior direction with portion of thyroid and arytenoid cartilages, respectively (Fig. 8(b.1)). The dissection procedure yielded to a number ni of vocal-fold samples derived from each larynx Li, labelled as Li-Sj (j ∈ [1, …, ni], Fig. 8(b.7)). As indicated in Table 2, samples were constituted either with only the muscular layer (M), or with several layers (LP+EP, M+LP+EP). It is worth noting that for the specific case of fresh larynx L10, sample L10-S3 was cut into the region of highest collision, i.e., close to the narrowest glottis38. Several conditions of tissue conservation were used: (i) defrosting after preservation at −20 °C; (ii) cryopreservation at −80 °C using dry ice; (iii) pre-immersion in a dilute aqueous solution of ethanol with concentrations [C2H60] ranging from 30% to 100% and diffusion time δt ranging from 1 min to more than 5 days (for diffusion times larger than 24 h, the immersion was achieved in successive baths of increasing alcoholic concentrations36, i.e., 30%, 50% and 70%); (iv) pre-immersion in a 10%-formaldehyde (CH20) solution. Two different containment procedures were tested. Vocal folds dissected from L4 and L7 were released from their cartilaginous ends and confined into a conic container (maximal inner diameter 5 mm and wall thickness 1 mm) sealed at its boundaries and optionally filled with glue or alcohol (Fig. 8(b.8)). Vocal folds dissected from L6 and L10 were mounted in a dedicated tension-compression micro-press58 (Fig. 8(b.9)), with a chamber regulated at proper hygrometric conditions (100% RH), to explore the feasibility of future in situ tensile tests. Typical dimensions of the scanned samples were within 10 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm (Fig. 8(b.9)).

X-rays microtomography

Laboratory X-ray microtomography

Pre-tests were performed with a standard laboratory X-ray source (RX Solutions, 3SR Lab, Grenoble, France) equipped with a conical polychromatic and divergent beam (Hamamatsu L12161-07 source), allowing absorption imaging mode. Corresponding imaging parameters are reported in Tables 1 and 2 (italic lines)30,31. The scans were obtained with a number np of X-ray 2D radiographs onto a 1914 × 1580 pixel2 Varian flat panel detector, leading to a voxel size Vvox (varying from 123 to 453 μm3). Samples were exposed to a 360° rotation with respect to the X-ray source (step angle 360°/np varying from 0.07° to 0.25°), with an exposure time of 125 ms (respectively 400 ms) per radiograph for experiments on the whole laryngeal structures (respectively on dissected vocal tissues). To restrain the noise, an average of 6 radiographs per 2D image was used.

Synchrotron X-ray microtomography

Most of samples were imaged on the ID19 beamline of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facilities (ESRF, Grenoble, France), allowing advanced imaging possibilities thanks to: (i) a high photon flux in a homogeneous, parallel, monochromatic and highly coherent beam; (ii) the recording of phase images obtained by adjusting the sample-to-detector propagation distance, xc, using single phase retrieval imaging mode (Paganin)26. The interaction of X-ray with matter is generally described by the complex refractive index of the sample, n = 1 − δ + iβ, where δ is related to the phase-shift effects of the X-ray waves induced by the sample, and β determines their attenuation59,60. The term β is retrieved by recording the absorption images, i.e. for xc = 0, while δ can be retrieved using a single propagation according to Paganin’s work, provided that the ratio of the dispersive and absorptive aspects of the wave-matter interaction, δ:β, is known. The chosen imaging parameters are reported in Tables 1 and 2 for experiments achieved at “medium” and “high” spatial resolutions, respectively (i.e., at voxel size of 133 and 0.653 μm3, respectively)36,61–63. Corresponding optical set-ups are detailed thereafter:

Experiments on larynges

For these experiments, two optical set-ups were tested:

For laryngeal samples L4 to L8, a first series of scans was achieved using the mechanical set-up shown in Fig. 8. Two extreme phonatory positions were acquired sequentially for each sample: at rest in a first time, and at maximal macroscopic stretch of the vocal folds achieved by cricothyroid approximation in a second time. The X-ray beam was adjusted using filters (2.8 mm Al, 0.14 mm Cu), an average energy E of 65 keV (I = 200 mA) and a wiggler gap of 95 mm. The transmitted beam was converted into visible light by a LuAg scintillator (thickness 500 μm), and recorded using a CCD camera (FReLoN-2K, 2048 × 2048 pixel2 chip, 14-bit dynamic range, FTM mode)64,65. The combination of the optics, using a sample-to-detector distance xc = 1.2 m in average, with the pixel size of the CCD (142 μm2) allowed to work at “medium” spatial resolution, i.e. with an effective voxel size of 133 μm3. 2D projections were collected according to the half-acquisition mode to obtain a 3D field-of-view of maximal size 3587 × 3587 × 600 voxels for each rotational acquisition. 4900 projections were acquired over the 360° rotation of samples. The beam exposure time was 100 ms per projection. Three rotational acquisitions were necessary to fully cover the whole vocal-fold tissue along its longitudinal axis (anteroposterior direction). These acquisitions were taken sequentially with an overlap of 127 slices (1.60 mm) from the angle of the thyroid cartilage. In the end, the scan duration was of 10 min and the total acquisition time about 1 h to scan both phonatory positions per larynx.

For sample L9, the optical set-up was modified so as to raise the sample-to-detector distance up to xc = 11 m and thereby maximise the phase-contrast effect61,62, by placing the sample in the ID19′s monochromator hutch (allowing a propagation distance up to 14 m). Filters were updated (2.8 mm Al, 0.7 mm Cu, 0.28 mm Au), the average energy was kept at around 60 keV, and the wiggler gap fixed at 61 mm. Placed in a single static geometry at rest, sample L9 was scanned in this optical “far-field” configuration yielding to a volume of 3706 × 3706 × 600 voxels (other collection parameters being as above).

Experiments on dissected vocal folds

For these experiments, the optical set-up was changed to work at “high” spatial resolution, i.e. at a voxel size of 0.653 μm3. In addition, a GGG10 scintillator and a PCO Edge 4.2 camera (SN 62000031, 2048 × 2048 pixel2 chip, no binning, FFM mode) were used, allowing fast and highly contrasted imaging. The acquisition parameters were characterised by a 19 keV beam energy, an undulator gap of 21 mm, a sample-to-detector distance xc = 40 mm in average, and a beam exposure time of 20 ms per radiograph. Several acquisitions were taken sequentially to cover the full height and width of the vocal-fold sample, with a field of view displaced by 1 mm-step in longitudinal and transversal directions, yielding to an overlap of 300 μm. In the end, the scan duration was within 1–2 min and the total acquisition time about 1 h 35 min per sample.

Image processing

After reconstruction of the scans using Paganin’s method for phase retrieval coupled with filtered back-projection26 and removal of tomographic artefacts such as rings, the resulting 3D and greyscale images were analysed using Fiji®, Avizo® and Matlab® routines. Some of them were automatically segmented using standard smoothing and thresholding algorithms implemented in these software, to get meaningful 3D views (Figs 2(a), 3(c) and 4(d)) and to analyse the vocal-fold structure in detail (Figs 5(b), 6 and 7). In some cases, this was not possible. Thus, to pursue the quantitative analysis, manual image thresholding was carried out using Fiji® and a graphical tab (Wacom Cintiq 22HD touch). For example, the geometries of two vocal folds and the sublayers of their lamina propria were tracked on images acquired at “medium” spatial resolution (voxel size of 133 μm3), as shown in Fig. 5(a). Similarly, some individual muscle fibres and ECM fibre bundles were extracted from the “high” resolution images (voxel size of 0.653 μm3), to analyse their geometry (Figs 6(a) and 7(a)). Then, various operations were realised, to extract from these 3D images some relevant qualitative information and quantitative descriptors:

Vocal-fold elongation

From the segmented images of the larynges acquired before and after the rocking movement of the thyroid cartilage into the dedicated set-up (Fig. 8(a)), the local elongation of the vocal folds λ was measured thanks to the glass beads stuck on them. For that, beads were easily isolated from the rest of the larynx using thresholding algorithms (Fiji®), as illustrated in Supplementary Figs S7 and S8. The positions of the bead centres of mass were then detected with the 3D Particle Analyser plug-in of Fiji®. Their relative distance l0 and l was calculated in the non-deformed and deformed configurations respectively, to estimate the vocal-fold elongation λ = l/l0.

Thickness of the lamina propria

A crop of the 3D image of larynx L9 was achieved in order to focus on the lamina propria structure at the millimetre scale. After manual segmentation (see above), the spatial thickness of the extracted lamina propria was computed using the Local Thickness plug-in of Fiji®66,67.

Multiscale orientation of fibres

The global 3D structural anisotropy of the muscle fibres was estimated from the greyscale image of larynx L9 acquired at “medium” spatial resolution (voxel size of 133 μm3), thanks to the fibrous textures detected in the vocalis. Notice that this operation was not possible in the lamina propria, where no well-defined fibrous texture was observed at this scale. Thanks to the 3D images recorded at “high” spatial resolution (voxel size of 0.653 μm3), the local 3D structural anisotropy of muscle fibres in the vocalis was also estimated, as well as the global 3D structural anisotropy of ECM fibres in the lamina propria. Whatever the tissue and spatial resolution, the following processing route was used for each considered Region Of Interest (ROI) – see Supplementary Figs S5 and S6: First, to enhance the grey-level gradients of the fibrous phases, 3D images were subjected to a coarse thresholding process, and a series of 3D smoothing and morphological operations (median filter, hole filling, opening/closure sequences). Second, the 3D Euclidean distance map was calculated in the considered ROI. Therewith, a home-made Matlab® code was used (i) to compute the gradients of grey levels in the as-treated ROI with a centred finite difference scheme, and (ii) to build from these gradients 3D structure tensors68 for the N voxels i of the ROI. For that purpose, the lateral size of the Gaussian-shaped windows used to compute structure tensors was adapted to the size of the objects to be characterised: 21 voxels (2733 μm3) for the muscle fibres of Fig. 5(b), 17 voxels (113 μm3) for those shown in Fig. 6(a), 21 voxels (133 μm3) for the ECM fibres of Figs 7(a) and 7 pixels (2 μm) for those shown in Fig. 7(b). Then, the discrete 3D Orientation Distribution Function (ODF) of the minor eigen- and unit vectors pi of the structure tensors was built. Such vectors, locally parallel to the fibres, can be expressed in the reference frame of the ROI (ex, ey, ez), as follows:

| 2 |

where 0 ≤ θi ≤ 180° is the angle between pi and ez, and where 0 ≤ φi ≤ 180° is the angle between the projection of pi in the (ex, ey) plane and ex. The first non-zero moment of this ODF, i.e. the 3D second-order fibre orientation tensor A69, was derived as a compact and meaningful descriptor of the fibre orientation in the ROI:

| 3 |

Waviness of fibres

As shown in the 3D images (Figs 3(c), 4(d) and 6(a)), muscle and collagen/elastin fibres exhibit a quasi-periodic wavy shape. Thus, in a given ROI, we scrutinised two sets of orthogonal slices comprising the main fibre direction eu, i.e. slices within the planes (eu, ev) and (eu, ew) as sketched in Fig. 5(b): eu is defined as the main eigenvector associated to the major eigenvalue of the fibre orientation tensor A, ev and ew being eigenvectors related to the second and third eigenvalues respectively. Thereby, the spatial periods λuv (respectively λuw) as well as the magnitudes R0uv (respectively R0uw) of the quasi-periodic shape of fibres were estimated. This was done by manually clicking at least 50 data per descriptor.

Sections of muscle fibres

Two methods were used to analyse the size and shape of the sections of muscle fibres. Both of them used “high” resolution 3D images of the vocalis (voxel size of 0.653 μm3). The first method consisted in analysing slices perpendicular to the mean orientation of muscle fibres. As depicted in the inset of Fig. 6(b), the edges of muscle fibres were detected using an edge detection subroutine (Matlab®). Then, the length P of each fibre’s edges was estimated, together with the surface A of the closed area they defined, the equivalent fibre diameter , the roundness of fibre and the position of their centre of mass xG. During this process, muscle fibres that were misaligned, i.e., with the tangent trajectory of their centre of mass xG too far from the main orientation of muscle fibres, were discarded. The same quantities were measured with the second method, which was applied along the whole cross sections perpendicular to the centreline of the muscle fibre that was manually extracted from its network (see bottom panels of Fig. 6(b)).

Histological analyses

A standard histological campaign with staining and 2D optical microscopy was also conducted to compare and validate the 3D images obtained with high-resolution X-ray synchrotron tomography. To this end, the vocal-fold tissue of fresh larynx L10 was characterised with both imaging techniques, using two excised samples from the right and left vocal folds, respectively for tomography (L10-S3 in Table 2) and for standard 2D histology. The latter sample, noted L10-S5, was first fixed directly after body excision by two successive baths containing a standard solution of 4% neutral buffered formalin for 1 h each (no freezing phase). Water was then removed using a series of ethanol baths (progressive concentrations of 70%, 80%, 95%, 100%, 100%, 100%; bath duration 1 h) and the sample was cleared with xylene, miscible with paraffin (two baths of 1 h). The tissue was infiltrated with liquid paraffin at 50 °C (two baths of 1 h) and then kept in a cold atmosphere (4 °C). It was then cut into 3 μm sections using a microtome, floated on a warm water bath to remove wrinkles, picked up on a glass microscopic slide and then sequentially plunged into xylene, alcohol and water baths, thereby reversing the embedding process so as to get the paraffin wax out of the tissue, and allow water-soluble dyes to penetrate the sections. Finally, different stains were chosen to enhance contrast under optical microscopy (resolution 0.2 μm): Hematoxylin-Eosin-Saffron (HES), Reticulin (modified Gordon and Sweets stain, Reticulum II staining kit, Roche) and Masson Trichrome were used to reveal both Type I and Type III collagen fibres (the latter being also called “reticular” fibres), whereas an Elastic stain allowed elastin fibres to be emphasised (see Supplementary Fig. S3).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the ESRF proposal MD-957 and shift IN-996 (ID19 beamline), the LabEx Tec 21 (Investissements d’Avenir - grant agreement n° ANR-11-LABX-0030), the AGIR-PEPS 2015 FIBROSCILLE (UGA-CNRS) and the INSIS PEPS 2016 MICROPLI (CNRS). We would like to thank Philippe Masson, Clare Peine, Stéphane Priem, Véronique Curri, Guillaume Bravais, Maxime Terrien, Carole Neuville, Emilie Mathieu, Florian Martoïa, Vincent Fernandez and Edward Andò for their helpful assistance.

Author Contributions

L.B., L.O., N.H.B. and P.C. designed the project. L.B., T.C., L.O., N.H.B., S.R.D.R., X.L., B.F., Y.R., A.M.L. and P.C. were involved in the preparation, conception and realisation of the microtomographic experiments. Y.R. and P.C. ensured the biological tissues’ excision and conservation. X.L. designed and processed the 3D-printed containment set-up for laryngeal pieces. S.R.D.R., E.B. and B.F. performed the optimisation of the ESRF optical set-ups and the X-ray scan acquisition. A.M.L. conducted the histological experiments. L.B., T.C., L.O. and N.H.B. processed the collected data and analysed the results. T.L. and T.C. were involved in the 3D orientation map calculations. L.B., T.C., L.O., N.H.B., S.R.D.R. and A.M.L. wrote and reviewed the main manuscript text.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study (≈1.5 To) are available from the corresponding author on request. An open access upon the ESRF data portal is also possible, according to the ESRF data policy (https://www.esrf.eu/datapolicy).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-31849-w.

References

- 1.Herzel, H., Berry, D., Titze, I. & Steinecke, I. Nonlinear Dynamics of the Voice: Signal Analysis and Biomechanical Modeling. Chaos (American Institute of Physics)5(1), 30–34 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Titze, I. R. Principles of voice production (National Center for Voice and Speech, Iowa, USA, 2000), 2nd edn.

- 3.Lucero J. Oscillation hysteresis in a two-mass model of the vocal folds. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 2005;282:1247–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jsv.2004.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunter EJ, Titze IR, Alipour F. A three-dimensional model of vocal fold abduction/adduction. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2004;115(4):1747–1759. doi: 10.1121/1.1652033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remacle A, Morsomme D, Finck C. Comparison of vocal loading parameters in kindergarten and elementary school teachers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2014;57:406–415. doi: 10.1044/2013_JSLHR-S-12-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirano M. Morphological structure of the vocal cord as a vibrator and its variations. Folia Phoniatrica. 1974;26:89–94. doi: 10.1159/000263771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrett CG, Coleman JR, Reinisch L. Comparative Histology and Vibration of the Vocal Folds: Implications for Experimental Studies in Microlaryngeal Surgery. The Laryngoscope. 2000;110:814–824. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200005000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madruga de Melo EC, et al. Distribution of collagen in the lamina propria of the human vocal fold. The Laryngoscope. 2003;113:2187–2191. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200312000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miri AK, Heris HK, Mongeau L, Javid F. Nanoscale viscoelasticity of extracellular matrix proteins in soft tissues: A multiscale approach. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2014;30:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coughlan C, et al. In vivo cross-sectional imaging of the phonating larynx using long-range Doppler optical coherence tomography. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep22792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deliyski D, Hillman RE. State of the Art Laryngeal Imaging: Research and Clinical Implications. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 2010;18:147–152. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283395dd4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobler JB, Zeitels SM, Chang EW, Yun SH. Dynamic imaging of vocal fold oscillation with four-dimensional optical coherence tomography. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1354–1362. doi: 10.1002/lary.20938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang EW, Kobler JB, Yun SH. Triggered optical coherence tomography for capturing rapid periodic motion. Scientific Reports. 2011;1:1–7. doi: 10.1038/srep00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maturo S, Benboujja F, Boudoux C, Hartnick C. Quantitative distinction of unique vocal fold subepithelial architectures using optical coherence tomography. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 2012;121:754–760. doi: 10.1177/000348941212101109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrera VLM, et al. 11.7 Tesla magnetic resonance microimaging of laryngeal tissue architecture. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:2187–2194. doi: 10.1002/lary.20643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen T, et al. A New Method of Reconstructing the Human Laryngeal Architecture Using Micro-MRI. Journal of Voice. 2012;27:555–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klepacek I, Jirak D, Duskova Smrckova M, Janouskova O, Vampola T. The Human Vocal Fold Layers. Their Delineation Inside Vocal Fold as a Background to Create 3D Digital and Synthetic Glottal Model. Journal of Voice. 2016;30:529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miri AK, Tripathy U, Mongeau L, Wiseman PW. Nonlinear laser scanning microscopy of human vocal folds. The Laryngoscope. 2012;122:356–63. doi: 10.1002/lary.22460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelleher JE, Siegmund T, Du M, Naseri E, Chan RW. The anisotropic hyperelastic biomechanical response of the vocal ligament and implications for frequency regulation: A case study. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2013;133:1625–36. doi: 10.1121/1.4776204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yildirim M, Durr N, Ben-Yakar A. Tripling the maximum imaging depth with third-harmonic generation microscopy. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2015;20:096013–1–10. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.20.9.096013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strupler, M. et al. Biomedical Optics in Otorhinolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery, chap. Nonlinear Microscopy of the Vocal Folds, 511–528 (Springer Scienc +Business Media New York, Boston, Massachusetts, 2016).

- 22.Kazarine, A. et al. Multimodal imaging of vocal fold scarring in a rabbit model by multiphoton microscopy. In Proc. SPIE 10069, MultiphotonMicroscopy in the Biomedical Sciences XVII, 100692E (2017).

- 23.Gabay, I. et al. Increasing the penetration depth for ultrafast laser tissue ablation using glycerol based optical clearing. In Proc. SPIE 9707, Dynamics and Fluctuations in Biomedical Photonics XIII, 97070X (2016).

- 24.Richardson DS, Licthman JW. Clarifying Tissue Clearing. Cell. 2015;162:246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laurencin, T. et al. 3D real-time and in situ characterisation of fibre kinematics in dilute non-Newtonian fibre suspensions during confined and lubricated compression flow. Composites Science and Technology 258–66 (2016).

- 26.Paganin D, Mayo SC, Gureyev TE, Miller PR, Wilkins SW. Simultaneous phase and amplitude extraction from a single defocused image of a homogeneous object. Journal of Microscopy. 2002;206:33–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2002.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vågberg W, Larsson DH, Li M, Arner A, Hertz HM. X-ray phase-contrast tomography for high-spatial-resolution zebrafish muscle imaging. Scientific reports. 2015;5:16625. doi: 10.1038/srep16625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dudak, J. et al. High-contrast X-ray micro- radiography and micro-CT of ex-vivo soft tissue murine organs utilizing ethanol fixation and large area photon-counting detector. Nature Publishing Group 1–9 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Shearer T, Bradley RS, Araida Hidalgo-Bastida L, Sherratt MJ, Cartmell SH. Three-dimensional visualisation of soft biological structures by X-ray computed micro-tomography. Journal of Cell Science. 2016;129:2483–2492. doi: 10.1242/jcs.179077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robert Y, et al. Helical CT of the Larynx: A Comparative Study With Conventional CT Scan. Clinical Radiology. 1996;51:882–885. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(96)80088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storck C, et al. Three-dimensional imaging of the larynx for pre-operative planning of laryngeal framework surgery. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2010;267:557–563. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-1129-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pufe T, et al. VEGF expression in adult permanent thyroid cartilage: implications for lack of cartilage ossification. Bone. 2004;35:543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joshi VM, Wadhwa V, Mukherji SK. Imaging in laryngeal cancers. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2012;22:209–226. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.107183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keyrilainen J, et al. Acta radiologica (Stockholm, Sweden: 1987) 2010. Phase-contrast X-ray imaging of breast; pp. 866–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeda T, et al. Ethanol fixed brain imaging by phase-contrast X-ray technique. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2013;425:22004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirea I, et al. Very High-Resolution Imaging of Post-Mortem Human Cardiac Tissue Using X-Ray Phase Contrast Tomography. Functional Imaging and Modeling of the Heart (FIMH) 2015;9126:65–73. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20309-6_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gray SD, Titze IR, Alipour F, Hammond TH. Biomechanical and histologic observations of vocal fold fibrous proteins. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 2000;109:77–85. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tao C, Jiang J, Zhang Y. Simulation of vocal fold impact pressures with a self-oscillating finite-element model. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2006;119:3987–3994. doi: 10.1121/1.2197798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirano, M. Structure and vibratory behavior of the vocal folds, In: Dynamic aspects of speech production (Tokyo University Press, 1977).

- 40.Roberts T, Morton R, Al-Ali S. Microstructure of the vocal fold in elderly humans. Clinical Anatomy. 2011;24:544–551. doi: 10.1002/ca.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirano, M., Kukita, Y., Ohmaru, K. & Kurita, S. Speech and language: advances in basic research and practice, vol. 7, chap. Structure and Mechanical Properties of the Vocal Fold, 271–97 (Academic Press, 1982).