Abstract

Background:

Trichomonas vaginalis infection is the most prevalent non-viral sexually transmitted infection worldwide. Interactions between this infection and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may cause adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm labour, premature rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, low birth weight and post-abortal sepsis.

Aims:

This study was aimed to determine the prevalence and risk factors of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among HIV positive pregnant women attending antenatal care at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), Lagos, Nigeria.

Methods:

This was an analytical cross-sectional study in which 320 eligible participants which included 160 HIV positive (case group) and 160 HIV negative (control group) pregnant women were recruited at the antenatal clinic of LUTH. A structured proforma was used to collect data from consenting participants after which high vaginal swabs were collected, processed and examined for Trichomonas vaginalis. The association between categorical variables were tested using the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test where applicable. All significances were reported at P<0.05.

Results:

The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among HIV-positive and HIV negative pregnant women were 10% and 8.1% respectively (P=0.559). Significant risk factors for Trichomonas vaginalis infection in the HIV-positive pregnant women were early Coitarche (P<0.005) and multiple lifetime sexual partners (P=0.021). There was no relationship between the Trichomonas vaginalis infection and the immunological markers of HIV infection.

Conclusion:

While this study does not provide grounds for universal screening of pregnant women for Trichomonas vaginalis infection as a tool of reducing HIV acquisition especially in pregnancy, campaign to create better sexual health awareness should be commenced as a way to contributing to the reduction in Trichomonas vaginalis infection during pregnancy and perinatal transmission of HIV.

Keywords: Coitarche, high vaginal swabs, perinatal transmission, sexually transmitted infection

Introduction

The Sub-Saharan Africa is the worst-affected region by the global HIV/AIDS epidemic, with about 25 million people living with HIV. [1, 2] This is 64% of the worldwide population of people living with HIV. [1, 2] The HIV/AIDS epidemic affects mostly women in the sub-Saharan Africa, with women and girls making up almost 57% of adults living with HIV and this are largely because heterosexual sex is a dominant mode of HIV transmission in the region. [1, 2]

Studies now suggest that Trichomonas vaginalis plays an important but under-reported role in increasing sexual acquisition and transmission of HIV. [3] Trichomonas vaginalis is a major co-factor in the amplification of HIV transmission. [4] Persons with Trichomonas vaginalis infection are more likely to develop HIV infection than the normal population due to the disruption of the epithelial monolayer cells leading to micro-ulcerations of inhabited tissues and increased passage of the HIV virus. [3, 5] Trichomonas vaginalis also induces immune activation, replication, and cytokine production which lead to increased viral replication in HIV-infected cells. [3, 5] Trichomonas vaginalis is a protozoan parasite and it is the most prevalent non-viral sexually transmitted infection worldwide. It causes the curable sexually transmitted disease called trichomoniasis. [6–12] According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the worldwide prevalence was 180 million cases [13] and to put this number into relative terms of other curable sexually transmitted infections, the global incidence of syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhoea as reported by the WHO were 12 million, 92 million and 62 million, respectively. [13] The majority of cases of trichomoniasis are localized in regions of low income or lack of resources for health care. [13] In the developing Africa countries, the prevalence rate ranges from 5 to 37%. [4, 5, 14–16]

Trichomonas vaginalis trophozoite is “an oval, parasite with five flagella and an axostyle project which may be used for attachment to surfaces and may also cause the tissue damage noted in Trichomonas vaginalis infections”. The infection is usually asymptomatic [15] and is mainly reported in women. [6, 17, 18] A shift in the normal acidity milieu of the vagina to a more alkaline one, promotes Trichomonas vaginalis growth. The disease is characterized in female patients by frothy-greenish, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, vulvovaginal irritation, dysuria and lower abdominal pains. [5, 17, 19, 20] The classic ‘strawberry’ appearance of the cervix and vagina (spots of punctuate haemorrhage) is seen in only 10% of women with T. vaginalis. [20]

Trichomonas vaginalis infection in pregnancy has been shown to be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. [21] These pregnancy outcomes include preterm labour, premature rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, low birth weight and post-abortal sepsis. [1, 21–23] It may also increase the vertical transmission of HIV due to a disruption of the vaginal mucosa. [24] Apart from the use of antiretrovirals, it has been postulated that routine detection and treatment of Trichomonas vaginalis infection in the HIV positive pregnant women may help reduce mother to child transmission of the virus, HIV shedding and subsequently improve birth outcome. There is currently paucity of studies on Trichomonas vaginalis infection in the HIV-positive pregnant woman in the black African continent. This study was therefore aimed to determine the prevalence and determinants of Trichomonas vaginalis infection in HIV positive pregnant women at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital and to also explore the relationship between markers of HIV disease and Trichomonas vaginalis infection among these HIV positive pregnant women.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This was an analytical cross-sectional study carried out among women attending the antenatal clinic of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH) from January to August 2016. LUTH acts mainly as a referral center for other government-owned and private hospitals in the state. It is on the mainland of Lagos State which has a population of over 9 million inhabitants. The hospital has an established Obstetrics and Gynaecology department that also offers services relating to the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV/AIDS (PMTCT). The annual antenatal clinic attendance and delivery rates in the hospital are 3000–3500 and about 2200 respectively.

Study population and recruitment criteria

The study population included known HIV-positive pregnant women aged 15 to 49 years who presented to the antenatal clinics for booking and antenatal care, as well as newly diagnosed HIV positive pregnant women above, detected through the screening programme of the institution. HIV negative women (matched for age [±3years] and parity [±1]) who presented to the antenatal clinics during the same period served as controls. Excluded from the study were pregnant women who have had treatment for Trichomonas vaginalis infection or vaginitis in the index pregnancy and women who were administered metronidazole tablets in the last 4 weeks prior to recruitment.

Sample size determination and sampling techniques

The minimum sample size (N) for each of the comparative group was obtained from the analytical formula for two independent groups. [25]

Where, P1 is the prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among pregnant HIV-positive women (9.4%) and P2 is the prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among pregnant HIV-negative women (1.9%) from a previous Nigerian study;[26] Zα is the unit normal deviate corresponding to the desired type I error rate (1.96); and Zβ is the desired statistical power (0.80). Therefore, N was calculated as 136 and with 20% provision for attrition and uncompleted follow-ups, the sample size calculated for each study group was 160. A total of 320 eligible women were recruited into the study using the consecutive sampling method after obtaining informed written consent from each participant. A total of 160 HIV-infected pregnant women were recruited with an equal number of HIV-negative controls (matched for age and parity) around the same the study period (January to August 2016).

Data collection

Data was collected from each participant using a structured proforma and from their medical and laboratory records at the medical records department and AIDS Prevention Initiative in Nigeria (APIN) clinic of the hospital respectively. As a standard of care, pregnant women who presented to the antenatal clinics for booking had provider-initiated counseling and testing (PICT) using the opt-out technique. Laboratory diagnosis of HIV infection among pregnant women was done using the serial rapid HIV testing algorithm as recommended by the current National Guidelines for Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV and the National Guidelines for HIV Counselling and Testing. [27, 28] A screening test kit (Determine) was used initially and if negative the ultimate test result was reported as negative and no further testing done. However if positive, a second rapid test kit (Unigold) was used. A third or tie-breaker test (Statpak) was done only when there was discordance between the first two rapid tests. The result of the third, tie-breaker test was reported as the ultimate result. The most recent CD4+ cells counts and viral load levels of the HIV-positive pregnant participants were copied from their antenatal clinic and/or APIN laboratory records.

Methods of sample collection and laboratory identification of Trichomonas vaginalis

High vaginal swab samples were then collected from each participant with the aid of a sterile disposable Cusco speculum and the sample carefully transported in a Stuart transport medium (STM) to the Microbiology laboratory of the hospital for analysis within 1 hour of collection. As described in details previously published by in Cheesbrough, [29] wet mounts of all swab samples were made in sterile normal saline on clean slides, covered with a cover slide and examined under the low power (10X) and high power (40X) magnifications for presence of motile trichomonads. Giemsa staining was also carried out as described by Mason et al [30] by making smear of the secretion on a slide, fixing it in absolute methanol for 1 minute and then allowed to dry. Diluted Giemsa stain was poured on the smear and allowed to stain for 10 minutes after which it was washed, air dried and examined under microscope with oil immersion (X100) magnification for presence of trichomonads.

Outcome variables of interest and data management

The study end-points were the prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among both the HIV-positive and HIV-negative pregnant women and the risk factors for Trichomonas vaginalis infection among these women. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS Statistical Package 22.0 for Windows (IBM corps. Armonk, NY, United States) and descriptive statistics were computed for all relevant data. All the quantitative data were tested for normality of distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. The location and spread of continuous variables were described by the mean and standard deviation (SD) respectively (if normal in distribution) or by the median and interquartile range (IQR) respectively (for skewed distribution). They were presented as mean ± SD or median (IQR) as appropriate. The association of Trichomonas vaginalis infection and HIV seropositivity in the pregnant women were tested using Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test where applicable to know the difference. All significance was accepted at P<0.05.

Ethical Approval

The study was carried out after obtaining approval from the Health Research and Ethics Committee of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria (Approval number – ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/517). Ethical principles according to the Helsinki declaration were considered during the course of the research. Most of the human subjects were adults and those below the age of 18 years were regarded as “emancipated minors” who were legally able to give informed consents by themselves. “Emancipated minor” is a person that is not of legal age to give consent (below 18 years of age in Nigeria) for a research study but who by virtue of marriage, pregnancy, being the mother of a child whether married or not, or has left home and is self-sufficient can be allowed to do so. All the participants read and signed an informed consent form prior to enrolment in the study; the investigators ensured strict confidentiality of all participants’ information. The biological samples were collected and sent for analyses at no cost to the participants and efforts were made to minimize discomfort to the participants during the sample collections and; all participants were given equal attention and optimal care throughout the study and they stand to benefit from the policy that may eventually emanate from the findings of this study. Pregnant women who were diagnosed with Trichomonas vaginalis infection during the course of the study were treated free-of-charge together with their partners using oral metronidazole 500mg twice daily for seven days. They were advised to abstain from sexual intercourse for the seven days treatment period.

Results

Table 1 showed that mean age (±SD) of the HIV-positive and negative pregnant women in the study were 29.3±6.1 and 30.0±5.3 years respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean age between the two groups (P= 0.110). The median (IQR) was 2.0 (1.0 – 4.0) each in the case and control groups respectively (P= 0.244). There were also no significant differences in the marital status (P=0.252), religion (P=0.219), educational level (P=0.097) and ethnic group (P=0.347) of the HIV-infected pregnant women when compared to their HIV-negative controls.

Table 1:

Socio-demographic characteristics of HIV positive and HIV negative pregnant women (n=320).

| Characteristics | Study participants | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV positive (%) | HIV negative (%) | ||

| Age (in years) | 0.110 | ||

| 15–19 | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) | |

| 20–24 | 34 (21.2) | 34 (21.2 | |

| 25–29 | 47 (29.4) | 47 (29.4) | |

| 30–34 | 33 (20.6) | 33 (20.6) | |

| 35–39 | 33 (20.6) | 33 (20.6) | |

| 40–44 | 10 (6.3) | 10 (6.3) | |

| Mean age (±SD) | 29.3 ± 6.1 | 31.8 ± 5.3 | |

| Parity | 0.244 | ||

| 0 | 29 (18.1) | 29 (18.1) | |

| 1–4 | 102 (63.8) | 102 (63.8) | |

| ≥ 5 | 29 (18.1) | 29 (18.1) | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0 – 4.0) | 2.0 (1.0 – 4.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.252a | ||

| Single | 5 (3.1) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Married | 155 (96.9) | 158 (98.7) | |

| Religion | 0.219 | ||

| Christianity | 88 (55.0) | 83 (51.9) | |

| Islam | 72 (45.0) | 77 (48.1) | |

| Education | 0.097a | ||

| Primary | 5 (3.1) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Secondary | 55 (34.4) | 41 (25.6) | |

| Tertiary | 100 (62.5) | 117 (73.1) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.347a | ||

| Yoruba | 94 (58.8) | 104 (65.0) | |

| Igbo | 53 (33.1) | 39 (24.4) | |

| Hausa | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Others | 12 (7.5) | 15 (9.3) | |

Fisher’s exact test; IQR – interquartile range

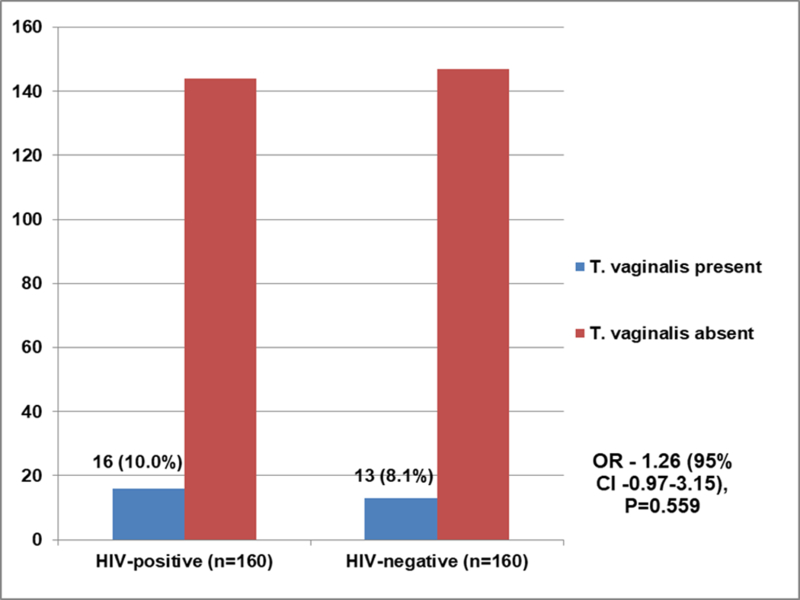

The overall prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection in the study was 9.1% (29/320). As shown in Figure 1, there was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among the HIV positive pregnant women and their HIV-negative counterparts (10.0% vs. 8.1%, P=0.559). However, on further analyses of the possible risk factors for Trichomonas vaginalis infection among the HIV-infected pregnant participants [Table 2], we did not find any statistically significant associations between Trichomonas vaginalis infection and vaginal douching (P=0.342) and inconsistent use of condom (P=0.174). We, however, found about 20-fold risk of Trichomonas vaginalis infection in women who had early coitarche (P<0.005) and about 9-fold risk in those who had more than one-lifetime sexual partners (P=0.021). In Table 3, we analysed the relationship between the markers of HIV infection and Trichomonas vaginalis infection in our pregnant participants and we found no statistically significant associations between the Trichomonas vaginalis infection and these markers i.e. viral load (P=0.648) and CD4+ cells counts (P=0.560).

Figure 1:

Distribution of participants with Trichomonas vaginalis infection (n = 320)

Table 2:

Risk factors for Trichomonas vaginalis infection among the HIV-infected pregnant participants (n=160)

| Risk factors | Trichomonas vaginalis infection | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present (%) | Absent (%) | |||

| Douching | ||||

| Yes | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | 1.91 (1.07–7.32) | 0.342a |

| No | 14 (9.5) | 147(91.9) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Condom use | ||||

| No | 13 (12.6) | 90 (87.4) | 2.21 (1.43–11.01) | 0.174a |

| Yes | 3 (5.3) | 54 (94.7) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Age at coitarche (in years) | ||||

| ≤18 | 12 (28.6) | 30 (71.4) | 21.82 (9.27–32.06) | 0.000a |

| >18 | 4 (3.4) | 114 (96.6) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Number of lifetime sexual partners | ||||

| ≥2 | 15 (13.9) | 93 (86.1) | 9.122 (4.03–14.85) | 0.021a |

| <2 | 1 (1.9) | 51 (98.1) | 1.00 (reference) | |

Fisher’s exact test

Table 3:

Relationship between markers of HIV infection and Trichomonas vaginalis infection among HIV-positive pregnant participants (n=160)

| HIV Infection markers | Trichomonas vaginalis infection | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present (%) | Absent (%) | |||

| Viral load (in copies/mL) | ||||

| ≥1000 | 2 (13.3) | 13 (86.7) | 1.35 (0.76–9.24) | 0.648a |

| <1000 | 14 (9.7) | 131 (90.3) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| CD4+ cells count (in cells/mm3) | ||||

| <500 | 13 (11.0) | 105 (89.0) | 1.61 (0.83–7.11) | 0.560a |

| ≥500 | 3 (7.1) | 39 (92.9) | 1.00 (reference) | |

Fisher’s exact test

Discussion

The distribution of the prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection in our study is almost similar to the reported prevalent distribution in similar study carried out at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital. [26] In the Ilorin study, the prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection was 9.7% among the HIV positive pregnant women and this is similar to the 10.0% prevalence obtained in our study. However, we reported a wide variation in the prevalence among the HIV-negative participants (8.1%) compared to the 1.9% prevalence reported from Ilorin. This could be because of better detection of the infection in our study due to the use of further staining with Giemsa unlike in the Ilorin study where the only method of detection of the infection was by the wet mount. Our study did not find any significant association between HIV-infection in pregnancy and Trichomonas vaginalis infection in contrast to most previous studies carried out within and outside Africa where such relationship were detected. [31–33]

These observed differences in the rates of infection in various studies could be due to variation in geographical location, community settings, population and diagnostic techniques. [17] Therefore direct comparisons are difficult and cannot be generalized. [17] The finding from this study could imply that Trichomonas vaginalis infection does not play a big role in the acquisition of the HIV virus among women in this environment and vice versa. A plausible explanation for this could be the abuse of metronidazole tablets for other ailments noted among most people in our environment. However, there is a need for a more robust study with larger sample size to substantiate this finding in the future.

Even though the practice of douching seems to be quite common in our environment, [34] our study was not able to prove that vaginal douching was a significant risk factor for Trichomonas vaginalis infection. In a survey done in the United States between 2001 and 2004 by Sutton et al, they found douching to be a risk factor for Trichomonas vaginalis. [35] Other studies suggested that certain feminine hygiene practices, such as douching and application of powder to the genitals, were significantly associated with Trichomonas vaginalis infection. [35] These hygiene practices have significant negative effects on the vaginal micro-flora and may increase the risk of acquiring Trichomonas vaginalis infection. [35] Condom use has been shown to reduce the prevalence of sexually transmitted disease generally and this was corroborated in a previous study that the use of condoms and depot Medroxyprogesterone were associated with a reduced incidence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection. [32] We, however, failed to demonstrate such relationship in this study but we cannot make any definitive inference from this as the number of participants who used condom consistently was rather small (35.6%). This was not surprising as majority of the participants were married (97.8%) and thus may not be expected to be using condom on a regular basis irrespective of their HIV-status.

We found an association between Trichomonas vaginalis infection and early age at coitarche among the HIV positive participants. This finding was similar to that of a study conducted in Giona, Brazil [32] and corroborated in a somewhat similar study by Sutton and colleagues in the United States. [35] An earlier age of coitarche is likely to lead to an increased in the number of lifetime sexual partners and thus an increased probability of acquisition of sexually transmitted infections. [36] In keeping with this hypothesis, our study demonstrated a significant positive relationship between Trichomonas vaginalis infection and increased number of lifetime sexual partners.

Whether immune status of HIV positive women, as reflected by the disease markers, influence the acquisition of Trichomonas vaginalis infection is still debatable. We found no significant association between Trichomonas vaginalis infection and the immunological status of the HIV infected pregnant women in this study. This is in keeping with the findings of other studies done in sub-Saharan Africa [37] and South America. [32] However a study done in North Carolina, USA showed that HIV positive women with viral load less than 400 copies/mL were less likely to have Trichomonas vaginalis infection. [3] It was also implied that the association between high viral loads and Trichomonas vaginalis infection suggest that it occurred more often in women who are receiving less than adequate treatment for HIV infection or are new to care. [3] It must be taken into account that almost all the HIV positive women in this study were on antiretroviral treatment which was provided for free. This would have had significant impact on the improvement of their immunological status.

Our study had several limitations and these include the possibility that some participants might have unknowingly taken metronidazole tablets and so did not volunteer such information. This is a hospital-based study and findings might not be representative of the general population. There is the possibility that some participants might have Trichomonas vaginalis infection not detectable using the wet-mount and Giemsa staining technique. Other more accurate screening/diagnostic methods such as culture and nuclear amplification techniques are expensive and not readily available. This being a cross-sectional study may have limitation such as temporal ambiguity, i.e., a lack of certainty on whether Trichomonas infection preceded HIV-infection or not as the relationship between Trichomonas vaginalis and HIV infection can be bi-directional. The study was greatly strengthened by the combined use of wet mount and Giemsa staining methods for the detection of Trichomonas vaginalis trophozoites that would have ordinarily been missed by the use of direct wet mount technique alone.

Conclusions

Even though we found out that more HIV-infected pregnant women had Trichomonas vaginalis infection compared to the HIV negative controls, our analysis did not to find any statistically significant difference. Important risk factors for Trichomonas vaginalis infection in the HIV positive pregnant women were early coitarche and multiple lifetime sexual partners. The immunological markers of HIV Infection were not shown to have a positive influence on the rate of acquisition of Trichomonas vaginalis infection. While this study does not provide grounds for universal screening of pregnant women for Trichomonas vaginalis infection as a tool of reducing HIV acquisition especially in pregnancy, campaign to create better sexual health awareness should be commenced as a way to contributing to the reduction in perinatal transmission of HIV.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating mothers and the members of the research team, including resident doctors, house officers, staff of the APIN clinic, Medical microbiology laboratory and the medical record department of our teaching hospital. KSO received partially supported from the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW010134. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Uneke CJ, Alo MN, Ogbu O, Ugwuoru DC. Trichomonas vaginalis infection in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive Nigerian women: The public health significance. Online J Health Allied Scs. 2007; 6(2): 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). AIDS epidemic update. UNAIDS/WHO; Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quinlivan EB, Patel SN, Grodensky CA, Golin CE, Tien H, Hobbs MM. Modeling the impact of Trichomonas vaginalis infection on HIV transmission in HIV-infected individuals in medical care. Sex Transm Dis. 2012; 39(9): 671–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sam-wobo SO, Ajao OK, Adeleke MO Ekpo UF. Trichomoniasis among Antenatal Attendees in a Tertiary Health Facility, Abeokuta, Nigeria. Mun. Ent. Zool. 2012; 7(1): 380–384. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Usanga V,L Abia-Bassey L, Inyang-etoh P, Udoh SF Ani E Archibong E . Trichomonas Vaginalis Infection Among Pregnant Women In Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria. The Internet Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009; 14(2): 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adegbaju A, Morenikeji OA. Cytoadherence and pathogenesis of Trichomonas vaginalis. Sci. Res. Essay. 2008; 3(4): 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lustig G, Ryan CM, Secor WE, Johnson PJ. Trichomonas vaginalis: Contact-Dependent Cytolysis of Epithelial Cells. Infect Immun. 2013; 81(5): 1411–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Der Pol B, Kwok C, Pierre-Louis B, Rinaldi A, Salata RA, Chen P, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis infection and human immunodeficiency virus acquisition in African women. J Infect Dis. 2008; 197(4): 548–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olorode OA, Mark OO, Ezenobi NO. Urogenital Trichomoniasis in Women in Relation to Candidiasis & Gonorrhea in University of Port- Harcourt Teaching Hospital. Afr. J. Microbiol Res. 2014. 8(26): 2482–85. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adeoye GO, Akande AH. Epidemiology of T.vaginalis among women in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria. Pak.J.Biol.Sci. 2007. 10(13): 2198–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mavedzenge SN, Pol BV, Cheng H, Montgomery ET, Blanchard K; de Bruyn G Epidemiological synergy of Trichomonas vaginalis and HIV in Zimbabwean and South African women. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37(7): 460–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Secor WE, Meites E, Starr MC, Workowski KA. Neglected Parasitic Infections in the United States: Trichomoniasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014; 90(5):800–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization: Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections – 2008: World Health Organization, Geneva, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okoko FJ. Prevalence of Trichomoniasis among Women at Effurun Metropolis, Delta State, Nigeria. CJ. Biol Sci. 2011; 4 (2):45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swygard H, Sena AC, Hobbs MM, Cohen MS. Trichomoniasis: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Sex Transm Infect. 2004; 80(2): 91–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chinedum OK, Ifeanyi OE, Ugwu UG, Ngozi GE. Prevalence Of Trichomonas Vaginalis Among Pregnant Women Attending Hospital In Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital In Edo State, Nigeria. J Dent Med Sci. 2014; 13(9): 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston VJ, Mabey DC. Global epidemiology and control of Trichomonas vaginalis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008; 21(1): 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akpan IU. The Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis in Uyo Local Government Area of Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Int. J. Modern Biol. Med 2013, 4(3): 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gülmezoglu AM, Azhar M. Interventions for trichomoniasis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 5 Art. No.: CD000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amadi AN, Nwagbo AK. Trichomonas Vaginalis infection among women in Ikwuano Abia State Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 2013; 17(3): 389–393. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preethi V, Mandal J, Halder A, Parija SC. Trichomoniasis: An update. Trop Parasitol. 2011; 1(2): 73–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donbraye E, Donbraye-emmanuel OO, Okonko IO. Detection of T.vaginalis among Pregnant women in Ibadan, South western Nigeria. World Appl.sci.J 2010; 11(12): 1512–1517. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolner-Hanssen P, Krieger J, Stevens CE. Clinical manifestations of vaginal trichomoniasis. JAMA. 1989; 261:571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cudmore S, Jeffrey Smith J, Garber G, Chang LT (ed.). Inducing Immune Protection against Trichomonas vaginalis: A Novel Vaccine Approach to Prevent HIV Transmission. In: HIV-Host Interactions 1st edition In: Tech; 2011; 299–322. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calculations of required sample size. In: Kirkwood BR, Sterne JAC (Ed.). Essential Medical Statistics. 2nd edition Hoboken, New Jersey (NJ): Blackwell Science Ltd; 2003; 413–28. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isiaka-Lawal SA, Nwabuisi C, Fakeye O, Saidu R, Adesina KT, Ijaiya MA, et al. Pattern of sexually transmitted infections in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women attending antenatal clinics in north-central Nigeria. Sahel Med J. 2014; 17(4): 145–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria. National Guidelines for the Prevention of Mother–to–Child transmission of HIV (PMTCT), 2010: 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria. National Guidelines for HIV counseling and Testing 2011: 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheesbrough M District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries, Part 2. Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason PR, Super H, Fripp PJ. Comparison of four techniques for the routine diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection. J Clin Path. 1976; 29: 154–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shafir SC, Sorvillo FJ, Smith L. Current issues, and considerations regarding trichomoniasis and human immunodeficiency virus in African-Americans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009; 22(1): 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinhero de lemos PA, Garcia-Zapata MTA. The Prevalence of Trichomonas Vaginalis in HIV- Positive & Negative patients in Referral Hospitals in Goiania, Goias, Brazil. Int. J. Med 2010; 5(2): 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutton MY, Sternberg M, Nsuami M, Behets F, Nelson AM, St Louis ME. Trichomoniasis in pregnant human immunodeficiency virus-infected and human immunodeficiency virus-uninfected Congolese women: prevalence, risk factors, and association with low birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999; 181(3): 656–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ekpenyong CE, Daniel NE, Akpan EE. Vaginal douching behavior among young adult women and the perceived adverse health effects. J. Public Health Epidemiol. 2014; 6(5): 182–191 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutton M, Stenberg M, Koumans EH, Mcqillan G, Berman S, Markactiz L. The Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis Infection among Reproductive-Age Women in the United States, 2001–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45:1319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olakolu SS, Abioye-Kuteyi EA, Oyegbade OO. Sexually Transmitted Infection among Patients attending the General Practice Clinic Wesley Guild Hospital, Ilesha, Nigeria. S Afr Fam Pract. 2011; 53(1): 63–70 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leroy V, Clerq A, Ladner J, Bogaerts J, Van de Perre P, Dabis F. Should screening of genital infections be part of antenatal care in areas of high HIV prevalence? A prospective cohort study from Kigali, Rwanda, 1992–1993. Genitourin Med. 1995; 71: 207–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]