Abstract

The “vocabulary problem” has long plagued the developers, implementers, and users of computer-based systems. The authors review selected activities of the Health Level 7 (HL7) Vocabulary Technical Committee that are related to vocabulary domain specification for HL7 coded data elements. These activities include: 1) the development of two sets of principles to provide guidance to terminology stakeholders, including organizations seeking to deploy HL7-compliant systems, terminology developers, and terminology integrators; 2) the completion of a survey of terminology developers; 3) the development of a process for HL7 registration of terminologies; and 4) the maintenance of vocabulary domain specification tables. As background, vocabulary domain specification is defined and the relationship between the HL7 Reference Information Model and vocabulary domain specification is described. The activities of the Vocabulary Technical Committee complement the efforts of terminology developers and other stakeholders. These activities are aimed at realizing semantic interoperability in the context of the HL7 Message Development Framework, so that information exchange and use among disparate systems can occur for the delivery and management of direct clinical care as well as for purposes such as clinical research, outcome research, and population health management.

Tremendous efforts by terminology developers and medical informatics researchers during the last decade have focused on the representation of health care data in a manner that facilitates the use and re-use of information. Despite these efforts, “the vocabulary problem” remains unsolved; that is, there are no widely available agreed-on standards for representing health care information.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 Moreover, evaluation studies indicate that there are gaps in the content covered by existing terminologies and that the majority of terminologies are not represented in a manner that facilitates implementation into computer-based systems or terminology management using knowledge-based approaches.9,10,11,12 In this article, we highlight selected activities of one organization, Health Level 7 (HL7), that is addressing the “vocabulary problem.”

Health Level 7 is a standards development organization, accredited by the American National Standards Institute, that is focused on interoperability for the interchange of health care data.13 The Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) defines interoperability as “the ability of two or more systems or components to exchange information and to use the information that has been exchanged.”14 Much of HL7's earlier work dealt with the functional part of the definition, “... to exchange information.” In 1996, HL7 created the Vocabulary Special Interest Group, which was promoted to a Technical Committee (TC) in 1998. The Vocabulary TC is focused on the semantic aspect of the definition, “... to use information.”

The overall objectives of the Vocabulary TC are to identify, organize, and maintain terms used in coded fields for HL7 messages. As a part of the efforts to meet these objectives, the Vocabulary TC assumes the responsibility to define a vocabulary domain for each coded entry message field. Health Level 7 proposes that the values in the vocabulary domains come from pre-existing terminologies in which they are available and adequate. When appropriate standard terminologies are not available, HL7 will develop a satisfactory solution. Thus, the work of the TC builds on and complements that of terminology developers, terminology integration organizations, and medical informatics researchers.1,4,6,7,8,15

In this article, we review selected activities of the Vocabulary TC that relate to vocabulary domain specification for HL7 coded elements, in order to inform terminology stakeholders (e.g., organizations seeking to deploy HL7-compliant systems, terminology developers, and terminology integrators) about the approaches being undertaken. As background, we define vocabulary domain specification and briefly describe the relationship between the HL7 Reference Information Model (RIM) and vocabulary domain specification.16 Our review focuses on the following activities: 1) the development of two sets of principles (principles for HL7-compliant terminologies and principles for HL7-sanctioned terminology integration efforts) to provide guidance to terminology stakeholders, 2) the completion of a survey of terminology developers, 3) the development of a process for HL7 registration of terminologies, and 4) the maintenance of vocabulary domain specification tables.

Background

Vocabulary Domain Specification

The basic idea of vocabulary domains is, intuitively, quite simple. A vocabulary domain is the set of allowed values for a coded field. If a message instance contains a marital status field, then the vocabulary domain for that field would consist of the allowed values for that field, which are, single, married, widowed, divorced, and separated. The reason for defining a vocabulary domain for coded fields is to strengthen the semantic understanding and computability of the coded information that is passed in HL7 messages. The assumption is that if there is a public definition of what values a coded field can take, systems on the receiving end of an interface will have a better understanding of how to use the data in their systems. The intent is that the coded data can be used in applications supporting direct patient care, outcome analysis and research, generation of alerts and reminders, and other kinds of decision support processes.

The Relationships Between Vocabulary Domain Specification and the HL7 RIM

The HL7 RIM is a coherent, shared information model that is the source of the data content of all HL7 mesasges. The evolving version 3 of the HL7 RIM has been developed through a consensus process that includes harmonization activities in order to incorporate efforts of HL7 message development groups. Message development groups focused on a particular subject domain (e.g., patient care, blood bank) develop messages for that domain and work with a subset of relevant concepts. A comprehensive description of the message development process is beyond the scope of this paper. We refer the reader to the Message Development Framework (MDF) document for details.16

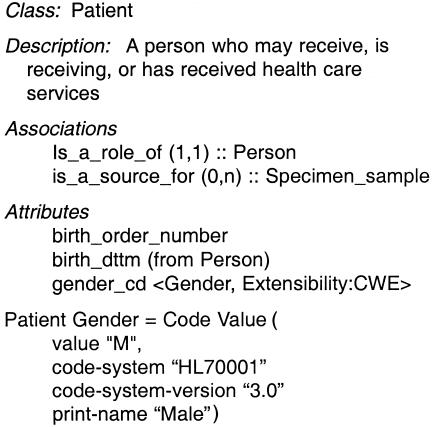

Each coded attribute in the RIM requires a vocabulary domain specification. As shown in ▶, gender_cd is an attribute of Patient. The gender_cd attribute has been assigned the vocabulary domain Gender. Its extensibility is “coded with exceptions,” meaning that the gender attribute should be valued from items in the gender domain, but free text exceptions are allowed. The vocabulary domain specification for the attribute, in this instance, comes from an HL7 table that lists all the allowed values for Gender. However, vocabulary domain specifications for coded attributes associated with the majority of concepts required for HL7 messages (e.g., diagnoses, signs, symptoms, body parts) will come from standard terminologies.

Figure 1.

A domain specification for gender.

HL7 Terminology Principles

Given HL7's commitment to using pre-existing terminologies when possible, two sets of principles were developed by the Vocabulary Technical Committee. The principles seek to assist stakeholders in determining which terminologies should be used in HL7 messages and facilitate terminology integration efforts in a manner consistent with the needs for HL7 messaging.

Principles for HL7-compliant Terminologies

The Vocabulary Technical Committee developed a set of principles regarding the manner in which end users should determine what terminologies should be included in HL7 messages for a specific organization.13 The development of these principles was viewed from different perspectives, which were challenging to resolve, but the current principles reflect a consensus among the participating committee members.

Implicit in these principles is the recognition that various organizations place different values on particular characteristics of terminology systems (e.g., cost, quality, timeliness of maintenance, interoperability, scientific validity). In addition, at least for the near future, “one size does not fit all” with regard to terminology system selection, and the specific decisions regarding the terminology systems need to be made by the organizations that deploy HL7-compliant systems. As organizations gain more experience in deploying terminology systems, the principles may expand and specific terminology systems may create de facto marketplace standards.

The specific agreed-on principles are:

The terminology must be compliant with the semantics of the HL7 message structure.

The terminology provider must be willing to participate in HL7-sanctioned interoperability efforts.

There must be an organization committed to the timely maintenance and update of the terminology.

Terminology license fees should be proportional to the value they provide to the enterprise and the end user but should not be out of proportion to the development and support costs of the terminology itself.

The terminology should be comprehensive for the intended domain of use.

Regulatory circumstances may require the adoption of specific terminologies. The use of such terminologies, provided that they are consistent with Principle 1 above, shall not be considered a deviation from the HL7 standard.

Because multiple terminology systems will be in use for the near future, the Vocabulary Technical Committee recognized the importance of supporting terminology interoperability efforts (such as the Unified Medical Language System [UMLS]17 and Open-GALEN,18 and created a set of guiding principles for facilitating these efforts for HL7 purposes.

Principles for HL7-sanctioned Terminology Integration Efforts

The following principles describe general ground rules for how terminology providers and terminology integrators should work together but intentionally describe nothing about the specifics of how terminologies should be integrated.13 There are many different options for how terminologies may be integrated into a functional integrated system, and these details are in the purview of the implementers, not that of the Vocabulary Technical Committee.

The specific principles are, first, that a source terminology provider must be willing to publish a limited conceptual model sufficient for HL7 implementation and allow HL7 to implement those or derivative information models in their applications without royalty. The HL7 organization is free to incorporate those or derivative information models in the HL7 standard.

Second, within the limitations stated by an appropriate written agreement, a terminology will be provided by the terminology provider to any HL7-sanctioned terminology integration organization (TIO) effort that wishes to integrate the terminology content with that of others. One possible candidate TIO is the National Library of Medicine's UMLS. For the purposes of an integration effort, the terminology integration organization is required to implement the terminology provider's system in a way that is approved by the terminology provider, and the terminology integration organization must distribute and license its integrated products in accordance with its agreement with the terminology provider. Participation in HL7-sanctioned terminology integration efforts does not imply that the terminology provider must relinquish any rights to its intellectual property.

Third, the terminology integration organization should enter into a written agreement with the terminology provider that details the assumption of liability pertaining to the accuracy of any resulting interoperability products.

Survey of Terminology Developers

The principles generated by the Vocabulary Technical Committee delineate a starting point in the development of mechanisms for using standard terminologies to specify vocabulary domains for coded data elements in HL7 messages. As another step in the path toward vocabulary domain specification for HL7 messages and semantic interoperability, we conducted a survey of terminology developers, to gain an understanding of current patterns of terminology maintenance and update, the vocabulary domains included in existing terminologies, and licensing and fee structures for use in HL7 vocabulary domain specification and messages.

Methods

The two-part survey was accompanied by a cover letter from the Vocabulary Technical Committee cochairs describing the purpose of the survey. The first set of questions focused on a description of the terminology and its potential vocabulary domain coverage for HL7 messages. Each respondent was asked to indicate, on a checklist of vocabulary domains corresponding to HL7 data elements, the domains for which the terminology could provide coded terms. They were also asked to list any additional domains for which the terminology might serve the needs of HL7 coded data elements.

The second set of questions related to licensing and fee structures for the use of the terminology for HL7 messaging purposes. They included four different scenarios: 1) use of the terminology by HL7 for vocabulary domain specification for HL7 messages, 2) use of the terminology within an organization and to send messages, 3) mapping to the terminology from another terminology to send a message, and 4) mapping to the terminology from another terminology to receive a message. The survey was distributed by mail to the developers of the source vocabularies of the UMLS, to developers of terminologies recognized by the American Nurses Association, and to pharmacy system knowledge-base vendors. The survey was also available on the HL7 Web site. Surveys were returned by mail or electronically. Survey responses were tabulated and descriptive statistics calculated.

Results

Of the 75 surveys distributed, 25 responses regarding 34 terminologies were recieved. The survey respondents (▶) included the providers of the major clinical and administrative terminologies as well as providers of specialized terminologies for alternative therapies, demographics, dentistry, medical devices, nursing, and pharmacy knowledge bases.8,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 In addition, the respondents represented those terminologies that evaluations have found to possess the best domain coverage.9,42,43 Nonrespondents included the providers of terminologies that were developed for specialized applications (e.g., symptom terms for diagnostic decision support systems) and for translations of the MeSH codes. Thus, the respondents reflected a representative sample of terminologies that would be used for vocabulary domain specification for HL7 purposes.

Table 1.

Terminologies Represented by Survey Respondents (N = 25)

| Alternative Billing Concepts (ABC)22 |

| American Dental Association, Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature (Dental Procedure)19 |

| American Dental Association, Systemized Nomenclature of Dentistry (SNODENT)20 |

| Centers for Disease Control, Common Data Element Implementation Guide (CDC)23 |

| First DataBank (FDB), nine terminologies—National Drug Data File, Master Drug Data Base, International Drug Data File, PIF, DDID (drug descriptor identification code), Multilex Drug Knowledge Base, FDBDX (disease code), Medical Conditions24 |

| Health Care Financing Administration, Procedure Coding System (HCPCS)25 |

| Home Health Care Classification (HHCC)26 |

| International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)27 |

| International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems Procedure Coding Systems (ICD-10-PCS)28 |

| International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC)29 / International Classification of Primary Care Drug Codes (ICPC Drugs)30 |

| Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes (LOINC)6 |

| Medicomp Systems (MEDCIN)31 |

| Multum MediSource Lexicon (Multum)32 |

| National Health Service [U.K.], Clinical Terms [formerly Read Codes] (NHS)33 |

| North American Nursing Diagnosis Association Taxonomy 1 (NANDA)34 |

| Nursing Intervention Lexicon and Taxonomy (NILT)35 |

| Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC)36 |

| Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC)37 |

| Omaha System (Omaha)38 |

| Patient Care Data Se (PCDS)39 |

| Perioperative Nursing Data Set (AORN)40 |

| Physicians' Current Procedural Terminology (CPT)21 |

| Russian translation of MeSH (R MeSH)41 |

| Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED)8 |

|

Universal Medical Device Nomenclature System

(UMDNS)25 |

| NOTE: Abbreviations used in the text are shown in parentheses. |

The frequency of updates ranged from daily to irregularly and was related to the rate at which new knowledge is generated in the domain and to the demand for the new knowledge. For example, the terminologies of the drug knowledge-base vendors are updated daily, whereas the nursing terminologies are updated less often than yearly (▶). Almost all the terminologies were already included in or had been submitted or planned for submission to the UMLS as source vocabularies (▶).

Table 2.

Frequency of Updates and UMLS Status for Each Terminology

| Frequency of Terminology Updates* | UMLS Status† | |

|---|---|---|

| AORN | L | P |

| ABC | Q | I |

| CDC | M | P |

| CPT | A | I |

| Dental Procedures | A | P |

| FDB | W | I |

| HCPCS | A | I |

| HHCC | L | I |

| ICD-9-CM | A | I |

| ICD-10-PCS | A | I |

| ICPC/ICPC Drugs | L | I |

| LOINC | Q | I |

| MEDCIN | L | S |

| Multum | W | I |

| NHS | B, M (drugs) | I |

| NANDA | L | I |

| NIC | L | I |

| NILT | L | N |

| NOC | L | I |

| Omaha | L | I |

| PCDS | L | I |

| R MeSH | A | I |

| SNODENT | A | I |

| SNOMED | B | I |

|

UMDNS

|

A

|

I

|

| Note: The full title of each terminology appears in ▶. | ||

L indicates less than annually; A, annually; B, biannually; Q, quarterly; M, monthly; W, daily / weekly.

I indicates included; S, submitted; P, plan to submit; N, no plan to submit.

As shown in ▶, all vocabulary domains had at least two terminologies for which respondents reported contents for the domain, although seven terminologies had only one domain each. The broadest coverage across vocabulary domains was reported for MEDCIN, NHS, and SNOMED.* With the exception of SNOMED and NHS, only nursing terminologies (i.e., AORN, HHCC, and NOC) reported that outcome indicators were included. Additional domains reported by the respondents beyond those listed in the survey included dental diagnoses, dental procedures, external causes of injury, social history, medical history, family history, physical therapy, social work, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, disability, functional performance, occupations, and health knowledge and behaviors.

Table 3.

Vocabulary Domains Included in the Terminology, as Reported by Respondents

| Vocabulary Domain | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse drug reactions | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Allergies (e.g., drug, food) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Analytes | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anatomy | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Billing codes | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Chemicals | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief complaint | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Demographics | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Diseases | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Drug names | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Home health care | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Imaging orders | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Imaging findings | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Laboratory orders | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Laboratory results | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Medical diagnoses | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Medical devices | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Medical procedures | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Microorganisms | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nursing diagnoses | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Nursing interventions | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Nursing outcomes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Outcome indicators | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Reasons for health care visit | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Respiratory care | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Signs | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Symptoms | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Topography | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Trauma | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Vaccines

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Notes: R MeSH did not complete this portion of the survey; ICPC and ICPC Drugs were combined in a single response; and the nine FDB terminologies were combined in a single response. The terminologies are identified as follows: A indicates AORN; B, ABC; C, CDC; D, CPT; E, Dental Procedures; F, FDB, G, HCPC; I, ICD-9-CM; J, ICD-10-PCS; K, ICPC/ICPC Drugs; L, LOINC; M, MEDCIN; N, Multum; O, NHS; P, NANDA; Q, NIC; R, NILT; S, NOC; T, Omaha; U, PCDS; V, SNODENT; W, SNOMED; X, UMDNS. The domains are described as follows: 1 indicates a primary vocabulary domain for the terminology; 2, a secondary vocabulary domain for the terminology. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Seven respondents did not provide answers to the survey questions related to license and fee structures. However, several of these indicated that the survey had stimulated discussion of the license and fee structures for HL7 domain specification and messaging and that these issues were subsequently under review in their respective organizations. The majority of responses did not differentiate license and fees related to the four different scenarios of terminology use described in the questionnaire. The responses fell into three main categories. The first category comprised the public domain (terminologies (e.g., HHCC, ICD-10-PCS) that reported no license or fee for any use of the terminology. The second category included those terminologies (e.g., Multum, UMDNS) that require a license but no fee for the uses described in the survey. The terminologies in the third category reported that a license and fee would be required. Medcin and NANDA indicated that a nominal fee would be charged. Others (e.g., FDB, SNOMED, CPT) reported that the fee was negotiable dependent upon use.

Support for Terminology Users

HL7 Registration of Terminology Systems

The Vocabulary Technical Committee recognizes that organizations need information to help them determine which terminology systems they should deploy. While the resources of the Vocabulary Technical Committee do not enable it to collect, organize, and provide access to many pieces of information (e.g., evaluative studies of all terminologies), the Technical Committee determined that providing standardized documentation about how terminology systems adhere to the principles for HL7-compliant terminologies would be significant value to end users. Subsequently, the Technical Committee developed a nondiscriminatory process by which any terminology system may be registered by a sponsor.

The development of the HL7 registration system is intended to facilitate access to information regarding terminology systems for organizations implementing HL7 and to foster a spirit of cooperation between terminology providers and the HL7 organization by providing each stakeholder with a specific role in the development of semantically rich health care messages. The registration process includes the development of documentation for implementing organizations. The specific registration steps are listed in ▶. Once the terminology is registered, the terminology system sponsor has several obligations. First, advertisements that a system is registered with HL7 must include a prominent disclaimer stating that “HL7 registration does not imply that a system is necessarily appropriate for use in HL7 messages.” The obvious reason for this disclaimer is that HL7 does not have the resources or the inclination to do an exhaustive evaluation of these standard terminologies. Second, the registration documentation must be updated quarterly and demonstrate a move toward a more comprehensive specification of vocabulary domain values.

Table 4.

Steps for Health Level 7 (HL7) Registration of a Terminology System13

| 1. A terminology system sponsor (acceptable to the terminology development organization being sponsored) will identify themselves to the HL7 Vocabulary Technical Committee and will commit to the creation and timely update of the HL7 terminology registration documentation. |

| 2. The terminology system sponsor will complete the registration documentation and make the documentation available to HL7 for posting on the HL7 Web site. This registration documentation will describe how a terminology system is to be used in HL7 and will include an itemized description of how the terminology system meets the principles for HL7-compliant terminologies and an initial list of domain constraints for HL7 versions 2.x and 3.x in tabular form suitable for upload into a commericial database, as described in Chapter 7 of the Message Development Framework. |

| 3. The terminology system sponsor will respond to questions. Any HL7 member may ask clarifying questions regarding the principles and the domain constraints. These questions alone or the questions and their subsequent answers will become a permanent part of the registration documents. Questions deemed irrelevant by a majority of the Vocabulary Technical Committee co-chairs may be excluded from, or edited before inclusion into, the registration documentation. |

| 4. Completed registration documents will be submitted during a regular HL7 meeting. At the time of the next HL7 meeting, allowing for clarifying questions and incorporation of the answers for these questions into the registration documentation, the terminology system shall be considered registered. |

Domain Specification Database

The maintenance of a domain specification database is essential because vocabulary domain specifications are only useful if they can be resolved to a list of allowed values for the coded attribute to which they are attached. All vocabulary domain names are resolved against a set of HL7 tables that contain the definitions of the various vocabulary domains or, alternatively, point to external terminologies where the vocabulary domain specifications are defined. The assumption is that any process that needs to resolve a vocabulary domain name to the list of concepts that the vocabulary domain contains can do so by reference to the domain specification database or by reference to external terminology tables or services.

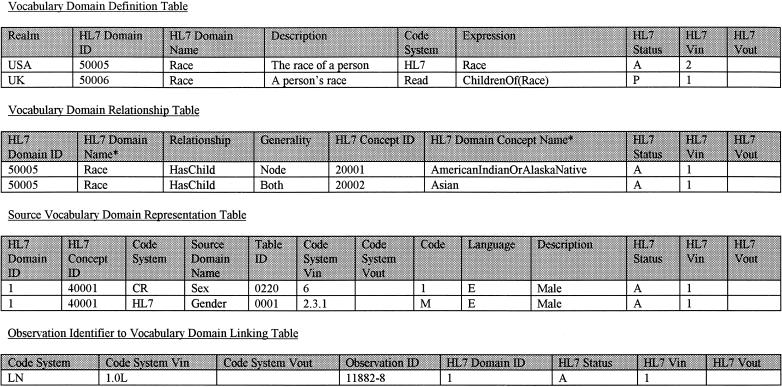

There are four primary data tables in the vocabulary domain specification database.16 Definitions related to table columns and examples of row entries are shown in ▶.

Figure 2.

Definitions and examples from the four primary data tables in the vocabulary domain specification database. In the Vocabulary Domain Relationship Table, the columns headed HL7 Domain Name* and HL7 Domain Concept Name* are shown for illustrative purposes only; the actual columns exist in the Vocabulary Domain Definition Table. Column Headings: Code indicates text string used in the code system to identify the concept; Code System, identifier of the code system from which the observation identifier was obtained; Code System Vin, version number of the code system at the time that the observation identifier was created; Code System Vout, version number of the code system at the time that the observation identifier was retired or deleted (blank value means that the row exists in the current version of the data); Description, textual representation of the meaning of the entry as it is represented in the code system from which it originated; Expression, an expression that defines how the vocabulary domain is derived from other preexisting vocabulary domains (e.g., union, difference, intersection); Generality, whether the concept in the HL7 Concept ID column should be interpreted as itself or whether it should be expanded to include its child concepts; HL7 Concept ID, the concept identifier of the item that is being included in the domain; HL7 Domain ID, unique numeric vocabulary domain identifier; HL7 Domain Concept Name, unique textual name assigned by HL7 for the vocabulary domain concept; HL7 Domain Name, unique textual name assigned by HL7 for the vocabulary domain; HL7 Status, status of the entry in the the domain specification database (e.g., Proposed, Rejected, Active, Obsolete, Inactive); HL7 Vin, version number of the domain specification database at the time this entry was added or updated; HL7 Vout, version number of the domain specification database at the time this entry was modified or deleted; Language, the language used in the description; Observation ID, observation identifier to which a vocabulary domain is being linked; Source Domain ID, the name of the domain in the original source that contains this concept; Realm, realm of use of the vocabulary domain (e.g., country or organization); Relationship, name of the relationship that exists between the domain and the concept listed in the HL7 Concept ID column.

The Vocabulary Domain Definition Table describes the high-level definition of a given vocabulary domain. It holds the name of the vocabulary domain and shows the relationship of the vocabulary domain to different realms of use (usually countries, but any organizational or political boundary is permissible), and to the various terminologies that are used to define the vocabulary domain. There is a new row for each realm of use and terminology providing values for the vocabulary domain. The structure of this table allows a vocabulary domain to be defined by recursive reference to other vocabulary domains.

The Vocabulary Domain Relationship Table records the relationship between HL7-maintained vocabulary domains and the concepts that are values in the domain. An HL7-maintained domain may be composed of individual concepts, other domains, or both.

The Source Vocabulary Domain Representation Table shows the relationship between HL7 concepts and codes and descriptions from specific terminologies. It allows a user of HL7 to see how the concepts in a given domain can be represented in a specific terminology. The structure of this table corresponds roughly to the logical structure of the version 2.× HL7 vocabulary tables. However, the content of the Source Vocabulary Domain Representation Table can be provided by HL7 or by any terminology provider that wants to use the HL7 domain specification database as a mechanism for making their terminology available for use in HL7 messages.

The Observation Identifier to Vocabulary Domain Linking Table is used to link an observation identifier, e.g., a LOINC code,6 with a vocabulary domain. This table is used when it is desirable to specify the exact vocabulary domain that should be associated with a coded observation identifier as used in a service event, assessment, or observation instance.

The general process of maintaining domain specifications is summarized in ▶.

Table 5.

General Process of Maintaining Domain Specifications13

| 1. The specification of vocabulary domains and vocabulary domain harmonization will be patterned after the RIM harmonization process and will happen in conjunction with RIM harmonization meetings. |

| 2. At least two Vocabulary Technical Committee members will be appointed as vocabulary facilitators to the message development Technical Committees by the co-chairs of the vocabulary Technical Committee and approved by the co-chairs of the relevant message development Technical Committee. People with a special interest may also be appointed to be the stewards of specific tables. |

| 3. For vocabulary domains that are shared by more than one message development Technical Committee, a single Technical Committee will be chosen as steward, with all interested parties having an opportunity to provide input, following the harmonization rules adopted for shared RIM projects. |

| 4. The message development Technical Committees have the ultimate responsibility to define the vocabulary domains referenced by the RIM objects for which they are the stewards. |

| 5. The vocabulary facilitators have the responsibility to see that good vocabulary practices are followed and to physically maintain the vocabulary domain specification database according to the definitions provided by the Technical Committees. |

| 6. Any new concepts created by Health Level 7 (HL7) Technical Committees will be submitted to HL7-registered terminology developers for potential inclusion in the standard terminologies. |

| 7. All HL7-registered terminology providers are welcome to provide mappings to HL7 domains using their terms and codes. The terminology providers are responsible for mapping their concepts to the concepts in the domain. Any proprietary terminologies used in HL7 specifications or interfaces must be properly licensed according to the licensing policies of the terminology provider. |

Discussion

The “vocabulary problem” has long plagued the developers, implementers, and users of computer-based systems.5,44 Tremendous strides have been made in recent years in the development and maintenance of standard terminologies that are atomic in nature and represented in a manner that renders them more suitable for implementation into and manipulation by computers.2,4,8,15,45 The activities of the Vocabulary Technical Committee complement the efforts of terminology developers and other stakeholders. The two sets of principles that were developed are aimed at providing guidance and support to various stakeholders in relationship to terminology requirements for HL7 messages. Our survey results indicate that standard terminologies are available and appropriate for providing vocabulary domain specifications (i.e., value sets) for many categories of coded elements for HL7 messages. Issues related to licenses and fees for use in vocabulary domain specifications require further discussion among stakeholders. The HL7 Vocabulary Technical Committee provides a forum for such discussions. The activities described in this article are aimed at realizing semantic interoperability in the context of the HL7 Message Development Framework so that information exchange and use among disparate systems can occur for the delivery and management of direct clinical care as well as for purposes such as clinical research, outcome research, and population health management.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this manuscript were adapted from Chapter 7 of the HL7 Message Development Framework.16 The authors thank the other members of the Vocabulary Technical Committee for their contributions to the thoughts and principles reflected in this article. They also thank Robert McClure, MD, for his assistance in the development of the terminology survey.

The preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by grant NIH-NR04423 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Terminology abbreviations are shown in ▶.

References

- 1.Campbell KE, Cohn SP, Chute CG, Shortliffe EH, Rennels G. Scalable methodologies for distributed development of logic-based convergent medical terminology. Methods Inf Med. 1998;37(4-5): 426-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chute CG, Cohn SP, Campbell JR. A framework for comprehensive terminology systems in the United States: development guidelines, criteria for selection, and public policy implications. ANSI Health Care Informatics Standards Board Vocabulary Working Group and the Computer-based Patient Records Institute Working Group on Codes and Structures. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5(6): 503-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cimino JJ. The concepts of language and the language of concepts. Methods Inf Med. 1998;37(4-5): 311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cimino JJ. Desiderata for controlled medical vocabularies in the twenty-first century. Methods Inf Med. 1998;37(4-5): 394-403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammond WE. Call for a standard clinical vocabulary. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(3): 254-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huff SM, Rocha RA, McDonald CJ, et al. Development of the LOINC (Logical Observations Identifiers, Names, and Codes) Vocabulary. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5(3): 276-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rector AL, Bechhofer S, Goble CA, Horrocks I, Nowlan WA, Solomon WD. The GRAIL concept modelling language for medical terminology. Artif Intell Med. 1997;9: 139-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spackman KA, Campbell KE, Cote RA. Snomed rt: a reference terminology for health care. In: Masys D (ed). AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997: 640-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Campbell J, Carpenter P, Sneiderman C, Cohn S, Chute C, Warren J. Phase II evaluation of clinical coding schemes: completeness, taxonomy, mapping, definitions, and clarity. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(3): 238-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chute CG, Cohn SP, Campbell KE, Oliver DE, Campbell JR. The content coverage of clinical classifications. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3(3): 224-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry SB, Warren J, Lange L, Button P. A review of the major nursing vocabularies and the extent to which they meet the characteristics required for implementation in computer-based systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5(4): 321-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry SB, Mead CN. Nursing classification systems: necessary but not sufficient for representing “what nurses do” for inclusion in computer-based patient record systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(3): 222-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.About HL7. Health Level 7 Web site. Available at: http://www.hl7.org. Accessed May 17, 2000.

- 14.Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. IEEE Standard Computer Dictionary: A Compilation of IEEE Standard Computer Glossaries. New York: IEEE, 1990.

- 15.Rossi-Mori A, Consorti F, Galeazzi E. Standards to support development of terminological systems for health care telematics. Methods Inf Med. 1998;37(4-5): 551-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health Level 7. Message Development Framework. Ann Arbor, Mich: Health Level 7, 1999.

- 17.Lindberg DAB, Humphreys BL, McCray AT. The Unified Medical Language System. Methods Inf Med. 1993;32: 282-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rector AL, Glowinski AJ, Nowlan WA, Rossi-Mori A. Medical concept models and medical records: an approach based on GALEN and PEN & PAD. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1995;2(1): 19-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Dental Association. Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature. Chicago, III: ADA, 1998.

- 20.American Dental Association. Systemized Nomenclature of Dentistry (SNODENT). Chicago, III: ADA, 1998.

- 21.American Medical Association. Physician's Current Procedural Terminology. Chicago, III: AMA, 1993.

- 22.Alternate Billing Concepts. Version 983. Las Cruces, NM: Alternate Link LLC, 1998.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control. Centers for Disease Control Common Data Element Implementation Guide. Atlanta, Ga: CDC, 1998.

- 24.First DataBank National Drug Data File, Master Drug Data Base, International Drug Data File, PIF, DDID, Multilex, Drug Knowledge Base, FDBDX, Medical Conditions. San Bruno, Calif: First DataBank, 1998.

- 25.Health Care Financing Administration. Health Care Financing Administration Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS): Level II Alpha-Numeric Codes. Baltimore, Md: HCFA, 1998.

- 26.Saba VK. The Classification of Home Health Nursing Diagnoses and Interventions. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, 1990.

- 27.United States National Center for Health Statistics. International Classification of Diseases: 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Washington, DC: NCHS, 1980.

- 28.Health Care Financing Administration. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) Procedure Coding Systems (PCS). Baltimore, Md: HCFA, 1998.

- 29.World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA). International Classification of Primary Care. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: WONCA, 1998.

- 30.World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA). International Classification of Primary Care Drug Codes. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: WONCA, 1998.

- 31.Medicomp Systems I: MEDCIN. Chantilly, Va: Medicomp Systems, 1998.

- 32.Multum MediSource Lexicon. Denver, Colo: Multum Information Services, 1998.

- 33.O'Neil MJ, Payne C, Read JD. Read Codes, Version 3: a user led terminology. Methods Inf Med. 1995;34: 187-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.North American Nursing Diagnosis Association. Nursing diagnoses: definitions and classification 1999-2000. Philadelphia, Pa: NANDA, 1999.

- 35.Grobe SJ. The Nursing Intervention Lexicon and Taxonomy: Implications for representing nursing care data in automated records. Holistic Nurs Pract. 1996;11(1): 48-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCloskey JC, Bulechek GM. Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC). 2nd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, 1996. [PubMed]

- 37.Johnson M, Maas M (eds). Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC). St. Louis, Mo: Mosby, 1997.

- 38.Martin KS, Scheet NJ. The Omaha System: Applications for Community Health Nursing. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders, 1992.

- 39.Ozbolt J, Fruchtnicht JN, Hayden JR. Toward data standards for clinical nursing information. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;1: 175-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleinbeck SVM. In search of perioperative nursing data elements. AORN J. 1996;63(5): 926-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russian Translation of MeSH. Moscow, Russia: State Central Scientific Medical Library, 1998.

- 42.Henry SB, Holzemer WL, Reilly CA, Campbell KE. Terms used by nurses to describe patient problems: can SNOMED III represent nursing concepts in the patient record? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;1: 61-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humphreys BL, McCray AT, Cheh ML. Evaluating the coverage of controlled health data terminologies: report on the results of the NLM/AHCPR Large Scale Vocabulary Test. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(6): 484-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Board of Directors of the American Medical Informatics Association. Standards for medical identifiers, codes, and messages needed to create an efficient computer-stored medical record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;1: 1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rector AL. Thesauri and formal classifications: terminologies for people and machines. Methods Inf Med. 1998;37(4-5): 501-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]