Abstract

Background:

Conducting research with dying persons can be controversial and challenging due to concerns for the vulnerability of the dying and the potential burden on those who participate with the possibility of little benefit.

Aim:

To conduct an integrative review to answer the question ‘What are dying persons’ perspectives or experiences of participating in research?

Design:

A structured integrative review of the empirical literature was undertaken.

Data sources:

Cumulative Index Nursing and Allied Health Complete, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Informit and Embase databases were searched for the empirical literature published since inception of the databases until February 2017.

Results:

From 2369 references, 10 papers were included in the review. Six were qualitative studies, and the remaining four were quantitative. Analysis revealed four themes: value of research, desire to help, expression of self and participation preferences. Dying persons value research participation, regarding their contribution as important, particularly if it provides an opportunity to help others. Participants perceived that the potential benefits of research can and should be measured in ways other than life prolongation or cure. Willingness to participate is influenced by study type or feature and degree of inconvenience.

Conclusion:

Understanding dying persons’ perspectives of research participation will enhance future care of dying persons. It is essential that researchers do not exclude dying persons from clinically relevant research due to their prognosis, fear or burden or perceived vulnerability. The dying should be afforded the opportunity to participate in research with the knowledge it may contribute to science and understanding and improve the care and treatment of others.

Keywords: Ethics, hospice care, palliative care, research subjects, research participation, terminally ill

What is already known about the topic?

Conducting research with dying persons can be controversial and challenging due to concerns for the vulnerability of dying persons and the potential burden that research might impose.

Access to dying persons for research purposes is limited due to perceived gatekeeping by treating clinicians, managers and policy-makers.

What this paper adds?

Dying persons value the opportunity to choose to participate in research, even when there is no hope of cure or life prolongation.

Vulnerability should not be assumed in the dying person.

Research participation can be beneficial to the dying person by providing an opportunity to help others, contribute to society, science and future patient care.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Dying persons should not be automatically excluded from research due to fear of harm or their perceived vulnerability.

Dying persons can be invited to participate in research if the research has potential to contribute to science and understanding and inform future patient care.

Introduction

Conducting research with dying persons and/or in hospice or palliative care settings has been described as controversial and challenging,1,2 with the ethics of such research widely debated.3–7 There is concern about the actual or potential vulnerability of dying persons5,6,8 and whether those nearing the end of life should be considered ‘too vulnerable’ to be involved in research.7 Yet there is evidence that research among vulnerable populations may not be harmful per se and that there may also be direct benefit to participants.9 Nonetheless, perceived vulnerability of dying persons results in gatekeeping, where access to dying persons for the purposes of research is limited.6,9–12 Denying a person the opportunity to participate in research on the basis of an assumption of vulnerability, however, is argued to be paternalistic.13

Research participation may provide dying persons opportunities to share their story, reflect upon experiences and contribute to knowledge generation.11 Recent research of cancer patients’ participation in research has demonstrated their willingness to be approached about participation in clinical trials in the hope of improving their own treatment, helping others and contributing to scientific research. This evidence, however, did not specifically relate to the perspectives of persons in the last stages of life.12

Reviews were published in 2010 and 2012, where the goal was to synthesise evidence related to patients’ experiences of participation in research.1,13 One focused on patients’ willingness and participation in clinical trials,1 and the other explored the views of patients (and others) on research participation when receiving end-of-life care.13 In both reviews, patient participants were in various stages of their disease trajectory. This trajectory ranged from immediately after diagnosis, while receiving curative treatment, as well as approaching the end of life.1,13 The end-of-life phase, also known as the terminal phase, can last days, weeks or months.14 This sensitive period, when people are approaching death, is when the question of conducting research to understand the experience is most controversial.

Aim

The aim of this integrative review was to answer the question: What are dying persons’ perspectives on, or experiences of, participating in research?

Design

A structured integrative review, following Whittemore and Knafl’s15 methodology, was undertaken. This approach was chosen because an integrative review is the broadest type of research review, allowing for the combination of diverse methodologies to enable a comprehensive understanding of problems or phenomena relevant to healthcare and policy.15 In contrast to a systematic review in which the randomised clinical trial and hierarchies of evidence are emphasised,16 an integrative review also allows for the combining of data from the theoretical as well as empirical literature.15

Search methods

A search of Cumulative Index Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL) Complete, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Informit and Embase databases was undertaken, using relevant search terms and common Boolean operators (Table 1), since inception of the databases till February 2017. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed and agreed upon by members of the team (Table 2).

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| dying OR ‘end of life’ OR palliative OR terminal OR hospice OR person OR patient | Searched with AND |

| participant OR subject OR inpatient OR resident OR client | |

| involve* OR experience* OR perspective* OR perce* OR attitude* OR feel* OR reflect* OR satisfact* | |

| participa* OR subject OR involv* | |

| ‘research participation’ OR ‘research subject*’ OR research |

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Published in English Reports primary research Subjects/participants were adult (18 years or older) Subjects/participants were identified or acknowledged as dying, terminal, terminally ill, acknowledged as having a short prognosis, receiving palliative care Where multiple subject/participant groups were included, the findings for each group were reported separately |

Secondary research including systematic reviews, literature reviews and integrative reviews Letters, commentary, editorials and opinion pieces Subjects/participants where the age of participants was not determinable and/or where subjects/participants were not acknowledged as dying, terminal, terminally ill, acknowledged as having a short prognosis, receiving palliative care |

Search outcome

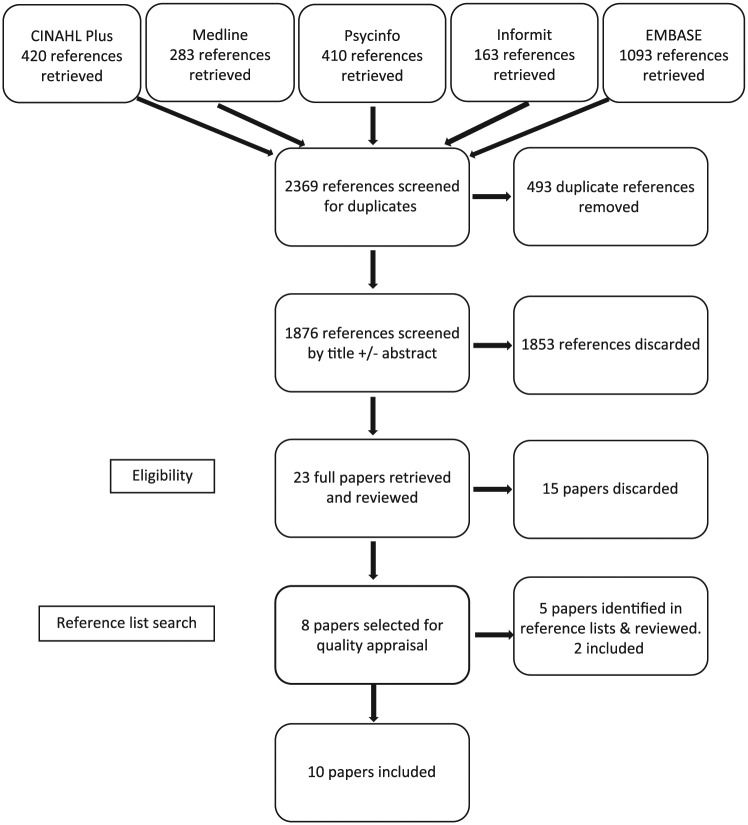

A staged screening process was undertaken involving the removal of duplicate references, screening of titles and abstracts, and subsequent full paper review. From the original 2369 references resulting from the search, 23 papers were retrieved for full review, and from these, 15 papers were discarded. The reference lists for the remaining eight papers were scanned for further relevant publications, and an additional two papers were identified that met the inclusion criteria. As a result, 10 papers were included in this integrative review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA.

Quality appraisal

There is no gold standard by which to appraise quality,15 but given that both qualitative and quantitative papers were included in this integrative review, a research critique framework produced by Caldwell et al.,17 which consists of 11 criteria suitable for assessing quality in both qualitative and quantitative papers, was chosen to evaluate the included papers. Caldwell et al.’s17 framework allows researchers to consider quality measures and the methodological strengths and weaknesses of qualitative and quantitative papers simultaneously. Using Caldwell et al.’s17 framework, the methodological quality of each included paper was independently assessed by two members of the research team (M.B. and L.B.). In total, 9 of the 10 papers scored 9/11 or higher against the quality criteria, and the remaining paper scored 8/11 (Table 3). While quality scores can be used as a criteria for exclusion, in this case, an a priori decision was made not to exclude papers on this basis, but instead to use the quality assessments to describe the quality of the literature in this area.

Table 3.

Quality appraisal.

| Author (year) | Quality appraisala |

Critical appraisal comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appraisal 1 | Appraisal 2 | ||

| Bellamy et al. (2011) | 11/11 | 11/11 | |

| Gysels et al. (2008) | 11/11 | 11/11 | |

| Head and Faul (2007) | 10/11 | 11/11 | Ethical issues not specifically detailed or addressed |

| Perkins et al. (2008) | 9/11 | 9/11 | Literature review not comprehensive; methodology identified, just justification of chosen method not comprehensive. |

| Pessin et al. (2008) | 10/11 | 10/11 | Ethical issues identified but could warranted from further detail |

| Ross and Cornbleet (2003) | 9/11 | 9/11 | Rationale for questionnaire and evidence of testing of the questionnaire not provided. No conclusion provided |

| Siu et al. (2013) | 8/11 | 10/11 | The literature review has a medical focus, hence not comprehensive. The process for analysis is not detailed. Discussion not comprehensive and lacked sufficient link with the other literature. Some grammatical errors in the paper. |

| Terry (2006) | 9/11 | 11/11 | Aim is reported differently between abstract and the body of the paper. The literature review is brief |

| White et al. (2008) | 11/11 | 11/11 | |

| Williams et al. (2006) | 11/11 | 11/11 | |

The 11-step quality appraisal framework from the study of Caldwell et al.17 is used.

Data abstraction and synthesis

The purpose of this stage of the review was to reduce the data from each of the included papers and identify common threads. Data from each paper were extracted to create individual evidence tables, detailing key features including author/s, year of publication, country, study design, purpose/aim, setting and sample, data collection methods/measures and findings.15 This approach enabled succinct organisation of data and ease of comparison between papers. The evidence tables were then used to facilitate constant comparative analysis to identify patterns, commonalities and differences.15 The process enables the evidence from diverse methodologies to be synthesised to produce a comprehensive portrayal of the topic of concern, and an integrated summation of the phenomenon presented in narrative form.15

Results

The papers included in this integrative review spanned studies conducted in five countries, and in each of the included papers, participants were identified as having a limited life expectancy, end-stage disease or receiving palliative or hospice care. Participants included were those receiving inpatient care, outpatient care or those previously involved in a palliative medicine clinical trial (Table 4).

Table 4.

Papers included in this review.

| Author (year) | Setting | Objective/research questions | Study design and method/measures | Sampling, recruitment and sample | Refusal rate and reasons (where detailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bellamy et al. (2011) | Three hospices in Auckland region ,New Zealand |

To explore the views of hospice users regarding their motivations for taking part in a study | Qualitative In-depth, semi-structured interviews were undertaken |

Sampling: purposive, to ensure heterogeneity; Recruited by: a third party (e.g. manager) responsible for each area and with knowledge of the patients’ medical condition; Sample: 21 hospice inpatients and outpatients; with cancer (n = 16), COPD (n = 1), MND (n = 3) and AIDS (n = 1). |

Not detailed |

| Gysels et al. (2008) | Large London teaching hospital ,United Kingdom |

To explore patients’ and carers’ preferences and expectations regarding their contributions to research | Qualitative Semi-structured open-ended interviews |

Sampling: purposive – patients were already enrolled in one of two other related studies; Recruited by: a clinician in the treating team/clinic; Sample: 64 palliative care outpatients with cancer (n = 30), COPD (n = 14), cardiac failure (n = 10) or MND (n = 10). |

21 (25%) patients declined to participate for the following reasons: no reason given (n = 6), too ill (n = 4), denies breathlessness (n = 4), did not want to be interviewed (n = 2), wanted to put episode behind them (n = 1), does not feel ‘up to it’ (n = 1), went into hospice (n = 1), thinks interview might hurt her (n = 1), and did not want to take part (n = 1) Others did not decline, but were not able to be included due to: death (n = 1), gatekeeping by wife (n = 2), not answering the phone (n = 1), not home for the appointment (n = 2), did not reply to the written information (n = 4) |

| Head and Faul (2007) | Hospice unit ,United States |

1. What type of research activities would they willingly commit to complete? 2. What factors would discourage their participation? 3. What are their general attitudes towards research and the professionals who conduct it? |

Quantitative Researcher-administered descriptive survey with pre-experimental, one-groups, posttest-only design |

Sampling: convenience – patients already admitted to a hospice programme; Recruited by: surveys were distributed by social workers working in the hospice, not involved in the study; Sample: 21 hospice unit inpatients (n = 12) and home patients (n = 9) described as terminally ill. |

Not detailed |

| Perkins et al. (2008) | Specialist palliative care unit in Cambridge, United Kingdom |

To investigate the views of palliative care patients on what should be the key priorities for future research | Qualitative Six focus groups of two to four patients each |

Sampling: convenience – patients already receiving care from the Hospice service; Recruited by: a study investigator; Sample: 19 patients including 8 inpatients and 11-day therapy patients with cancer and a prognosis of 6 months or less. |

Two (8%) patients declined to participate due to being too fatigued (n = 1) and did not feel well enough (n = 1) |

| Pessin et al. (2008) | 200-bed palliative care hospital in New York City ,United States |

To assess the burden and benefit of participation in research that investigated attitudes towards hastening death and other symptoms associated with end-of-life suffering among patients receiving palliative care | Quantitative Researcher-administered survey containing the Burden and Benefit Scale questionnaire |

Sampling: purposive – via 1383 consecutive admissions to the hospital as part of a larger study; Recruited by: not detailed; Sample: from the initial cohort of inpatients with end-stage cancer and a life expectancy of less than 2 months, three dropped out due to being upset by the questions, leaving 68 participants. |

179 (65%) patients declined to participate for the following reasons: did not want to be involved in research, did not want to discuss death and dying, and believing they were too ill. There was no difference between those who participated and those who refused according to age, race or religion. |

| Ross and Cornbleet (2003) | Specialist palliative care units ,United Kingdom |

To determine the willingness of patients receiving specialist palliative care to take part in clinical trials | Qualitative Structured interview of five questions, with answers recorded by the interviewer |

Sampling: convenience – patients admitted to the palliative care unit at least 48 h prior; Recruited by: a study investigator; Sample: 40 palliative care inpatients with advanced malignancy; Evidence of refusal to participate: one (2.5%) patient declined to participate. |

|

| Siu et al. (2013) | Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region & Clinical Oncology Department ,China |

To understand patients’ views on failing to gain expected beneficial outcomes from palliative medicine clinical trials by asking their reasons of being willing to participate in clinical trials, experiences during the process of clinical trials and whether they feel they have gained anything out of the experience | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews using a discussion approach rather than a question and answer format |

Sampling: purposive – patients with metastatic and progressive disease, who had previously participated in a palliative medicine clinical trial but unable to gain expected beneficial outcomes from interventions; Recruited by: not detailed; Sample: seven patients with metastatic cancer already participating in palliative chemotherapy trial or trialling drug for symptom control. |

No patients declined to participate. |

| Terry et al. (2006) | 20-bed hospice, part of the public hospital system but administered by the Sisters of Mercy, Singleton ,Australia |

To see whether terminally ill patients were indeed desperate for cure, whether cure was the only outcome of research they values and whether they did have difficulty distinguishing research from treatment | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews were conducted using open-ended predetermined questions, structured beforehand to cover broad areas |

Sampling: convenience – current hospice inpatients; Recruited by: a member of the palliative care team, other than the researchers or treating physician; Sample: 22 hospice inpatients described as dying. A total of 18 had advanced malignant disease. The diagnoses of the remaining four patients has been withheld to protect their identity. |

No patients declined to participate. |

| White et al. (2008) | Palliative Care service integrated within the oncology service at the Mater Misericordiae Hospital, Brisbane ,Australia |

To determine if patients with advanced cancer are interested in participation in research that does not involve anti-cancer therapy, particularly in the context of a RCT, and if so, what factors are important in their decisions | Quantitative Self-report questionnaire |

Sampling: convenience – patients known to the Palliative Care service; Recruited by: not detailed; Sample: 101 patients ‘with an active, progressive, far-advanced disease for whom prognosis is limited, and the focus of care is quality of life’. |

No patients declined to participate. |

| Williams et al. (2006) | Hospice services located across four south-eastern states (Alabama, Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi), United States |

To examine hypothetical interest in research studies of hospice patients and caregivers as compared to ambulatory senior citizens | Quantitative Self-report questionnaire |

Sampling: convenience – recruited from existing hospice patient group; Recruited by: a project coordinator at each site; Sample: 142 hospice patients enrolled in the hospice service for at least 1 week; Response rate: 396 surveys were initially distributed, indicating a response rate of 36%. |

N/A |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MND: motor neurone disease; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

From the analysis, four themes emerged: (1) the value of research, (2) desire to help, (3) expression of self and (4) participation preferences.

The value of research

Acknowledging that research and the pursuit of new knowledge was an essential part of the workings of a health institution,18 participants responded positively (85%) when asked about researchers and their ability to be honest about research participation.19 Understanding that their own care was likely informed by research evidence,18 participants affirmed that it was indeed ethical for dying patients to participate in research, and in fact, it was unethical not to include dying patients.20 Research participation was considered preferable to relying on doctors guessing how to treat terminally ill patients.18 Participants suggested there was a ‘freedom’ in being near death, with nothing to lose by voicing their opinion or saying precisely what they wished,18 underpinning their decision to participate. For others, participation in research was contingent on there being no possibility of it delaying their death since for them life prolongation was seen as a hazard, not a benefit.18

Desire to help

Desire to help was a dominant theme found in every study included in this integrative review. Participants spoke of the desire to help others, themselves and to aid research or researchers.

Desire to help others

Participants understood it was the knowledge gained from research that guided their treatment, and they wanted others to have the same benefit.18 In three studies, the desire to help others who may be in a similar position in the future was an important factor in patients’ decisions to take part in research.21–23 In relation to patients with motor neurone disease (MND), Bellamy et al.21 reported that patients made a conscious decision to take part in any research related to MND because they wanted to contribute in ways that raised awareness and knowledge about the disease, in the hope of saving others from going through the same experience.

The desire to help others was also reflected in Head and Faul’s19 survey findings, where 76% of patients suggested that they would likely participate if the research would benefit others with the same illness in the future. Likewise, White et al.24 reported that 82% of patients in their study were interested in participating in a trial that was unlikely to help them, but might help others in the future. Some patients said that when they had little time left to live, it was important they used that time to do something of enduring value,18 and one of the perceived benefits of research participation was to feel good about helping others.25

Desire to help self

Despite their terminal diagnosis, participants maintained a desire to help themselves in ways other than cure. Research participation offered an opportunity to benefit personally19 and was listed as one of the top three reasons for research participation.22 For some patients, research participation had the potential to make them feel better25 and was considered a valuable experience for self.23 Others suggested participation offered the opportunity to think about issues they had not necessarily considered or discussed.26

The desire to achieve symptom control rather than cure was identified in two studies.22,24 Other potential personal benefits identified by participants included the opportunity to obtain a referral for emotional distress26 and the belief they would be followed more closely by the clinician team, or perhaps receive better care as a result of participating.19,25 Others suggested that participation might be enjoyable,22 and in a study seeking feedback on various possible research studies, 84% of respondents were interested in a trial of pain medication, 81% expressed interest in a trial of a special mattress and 79% were interested in a trial of aromatherapy,24 all therapies that participants perceived to have potential to be beneficial.

Desire to contribute to research or help researchers

The desire to contribute to, or advance research, was identified as important in several of the included studies. Participants suggested that the importance of research,22 a desire to help the researcher27 and contribute to scientific knowledge19,27 and medical literature23 influenced research participation. The opportunity to enrich the lives of future patients23 through research was an important motivation for participation.

Expression of self

Participation in research was considered a positive experience because it offered an opportunity to feel engaged and validated and to express gratitude.

Feeling validated and engaged

The opportunity to participate in research was valued by participants as a way of feeling engaged with the world as a person beyond their illness.21 Others reported that research participation had made them feel special, offered a way to restore the balance of power and to be seen as an equal human being and was linked to living.21 Research participation was also seen as a way to think about and reflect on their own lives,23 offering the opportunity to participate in meaningful activity other than being the person living with a life-limiting illness21 or the dying person.18 Similar sentiments were expressed by survey participants, with ‘sense of purpose’ and ‘meaning to life’ identified as benefits of research participation.25 Others reported feeling a sense of contribution and appreciated the opportunity for social interaction that came with research participation.26 In another study, patients welcomed the opportunity to talk with an interested outsider and make sense of their experiences.27 This was particularly important for those who reported being unable to talk with others such as their treating team, family or clergy.26

Expressing gratitude

Participation also offered an opportunity for participants to have their say, give back to the services that they perceived had been supportive of them during the course of their illness,21 express their gratitude27 and say thank you for the care they received.21 Some saw it as their duty to give something back; and that an interview, for example, was the least they could do.27 ‘Because the staff have been good to me’ was one of the most frequently stated reasons for participation in research.22

Participation preferences

Participants in the included studies also provided insights into their preferences for participation. In relation to research recruitment, participants expressed a preference to be approached about research participation by staff familiar to them, with whom relationships had already been established,18,25 rather than an independent investigator.25 This approach was preferable as they could avoid the need to explain their situation or problems to a new person and addressed the concern that an independent researcher may not be able to cope with the issues of dying.18

Participants also expressed their preferences for types of studies they would participate in. In relation to clinical trials, even when the clinical trial was unlikely to help them, participants in the study by White et al.24 remained consistently positive about participation, if the trial was likely to help others in the future (82%), might help symptoms but not help the cancer (88%), when the clinical trial is quick and easy (94%) or when the doctors were very keen for the patient to participate (84%). In relation to placebo-controlled randomised trials, however, Terry et al.18 found that participants reported concerns based on the assumption that those in the placebo arm of a trial would suffer worse outcomes or receive no active treatment. Hence, active comparator trials were more acceptable to patients.18

Willingness to participate according to the level of burden associated with studies was explored in two studies. Willingness to participate reduced with increasing burden, where burden was related to invasiveness of treatment and level of commitment. Ross and Cornbleet22 measured willingness of participants to participate in three hypothetical studies. Factors that would reduce willingness to participate included a dislike of blood tests, uncertainty about the drug, lack of appeal for the proposed therapy, the burden of record keeping, that the study would upset them and that they didn’t have the associated condition or a need to talk.22 Willingness to participate was also explored by White et al.24 in relation to the level of study invasiveness. The majority of participants were interested in less-invasive studies such as pain education research, trialling a special mattress or aromatherapy. As the degree of uncertainty or invasiveness increased, willingness to participate decreased. For example, more than half of respondents stated they were not interested in trialling a new oral ‘pain killer’ of unknown benefit, and even less were interested in trialling an injection, epidural or spinal stimulator designed to reduce pain.24

Participants’ willingness to tolerate inconvenience daily, weekly and monthly was also measured by White et al.24 Approximately one-third of participants were willing to tolerate extra hospital visits, answer questions or complete a questionnaire, have extra blood tests or scans or take extra tablets, once a week. Participants were less willing to tolerate daily interventions, and more than one-third reported that they would not be willing over any time frame to have extra injections as part of a trial.24

Discussion

In the past, researchers have avoided research with vulnerable populations, such as dying persons, because of the prevailing perception that it would be too burdensome or perhaps even unethical.9,28 The dominant ethical principle associated with the question of research involving dying persons is respect.29 Respect in this context is about protecting the life, health, privacy and dignity of the human subject of research30 and recognising that each human being has value, autonomy and the capacity to make decisions for him or herself.29 With this in mind, researchers and clinicians should work to ensure dying persons are afforded the same level of respect and autonomy as others, including the opportunity to participate in research. To deny dying persons this opportunity on the basis of their life-limiting illness denies their right to autonomy. Evidence from this review demonstrates that dying persons not only value the opportunity to participate in research but also regard their contribution as important to themselves and others.

The evidence in this review also challenges assumptions related to recruitment. A common requirement of institutional review boards is that recruitment is undertaken via an independent third party to avoid potential coercion.8 However, consistent with previous research,25,31 this review suggests that dying persons may prefer to be approached about research by a member of their treating team with whom a relationship is already established. A way forward is for institutional review boards to allow recruitment by members of the patient’s treating team, where other measures, such as a silent opt-out process, in which potential participants can decline through inaction is in place.32

Of note is the inherent sampling bias of studies included in this review. By the very nature of research regarding participation preferences, the perspectives of dying persons who chose not to participate, are not included in this review. Where information about reasons for declining to participate are provided, the reasons vary, suggesting at the very least, that dying persons do maintain autonomy in decision-making when it comes to research participation, and can and do refuse to participate in research for reasons other than just their terminal illness.

How benefit is defined is also an important consideration in research involving dying persons. Institutional review boards are mandated to ensure that there is a reasonable likelihood that the populations in which the research is carried out stand to benefit from the results of the research.30 Hence, when dying persons are considered, any research that does not seek to improve their condition or benefit the person in some way may be considered unethical. This review has shown that benefit can and should be measured in ways other than life prolongation or cure. Altruism and the desire to be of help were dominant themes to emerge from this review, and are similarly reflected in other research involving patient cohorts with significant illness.9,10,13 Making a contribution to society, helping others and advancing research should also be considered benefits from research for the individual participant.4,9,12,33

The need for a concerted approach to expand evidence to underpin palliative and end-of-life care is well-documented.34 The benefits of enhancing healthcare through research are obvious, yet in palliative and end-of-life care, the reluctance and perceived difficulty of conducting research has meant that care provided to dying persons may be less likely to be based on research evidence.9 Although research with dying persons may be seen as more challenging, researchers can work to overcome these challenges in order to ensure that care provided to dying persons is underpinned by research evidence.9

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this review was the focus on research conducted with dying persons, specifically identified in the included manuscripts as either dying, terminal, terminally ill, having a short prognosis or receiving end-stage palliative care. This is an important distinction from other systematic reviews, where patients with cancer and other life-limiting diagnoses were included, but where death was not imminent and the focus of care was cure.

The integrative review design enabled research evidence derived from diverse methodologies to be synthesised, providing a comprehensive understanding of dying persons’ perspectives on, or experiences of, participating in research. This is critically important because assumptions made by clinicians and treating teams have historically limited access to dying persons for the purposes of research but this review provides evidence that gatekeeping may not necessarily be in the best interests of the dying person.

There are several limitations to this review. The database search retrieved numerous research publications about studies reporting on patients’ perceptions and/or experience of research participation, except the participant populations were not specifically described as dying. Rather, many included patients receiving curative and palliative care, where the findings are not separated. Hence, even though these papers may have had findings relevant to this review, they were excluded. As stated earlier, the findings of this review represent the views of those who participated in the 10 included studies, and the perspectives of those who declined participation is not as well-understood.

Conclusion

Previous reviews have explored clinical trial participation by dying persons, others have included participants with a life-limiting diagnosis, at various stages of their disease trajectory including immediately after diagnosis. This integrative review is the first to synthesise evidence related to dying persons’ perspectives on or experiences of participating in research. Given the expectation that care is evidence-based, understanding dying persons’ perspectives of research participation will enhance the future care of dying persons, if it is conducted with sensitivity and respect. Therefore, it is essential that researchers do not exclude dying persons from clinically relevant research, as a result of their prognosis, fear of burden or perceived vulnerability.

Rather, dying persons should be afforded the same opportunities as those seeking active treatment to participate in and contribute to research, where appropriate, with the knowledge that even if the research cannot result in an improvement to their condition, benefit may be measured in other ways, including contributing to the body of research evidence that informs the care of others. Researchers should be encouraged to undertake research involving those nearing the end of life if the intended research has the potential to contribute to science and understanding and inform future patient care.

Acknowledgments

M.J.B., M.B. and A.M.H were responsible for the study design; data collection and synthesis was done by M.J.B. and L.B; and M.J.B., M.B., A.M.H., and L.B. prepared the manuscript. All authors approve the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The authors disclose receipt of financial support from an Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellowship, from Deakin University, Australia.

References

- 1. White C, Hardy J. What do palliative care patients and their relatives think about research in palliative care? – a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2010; 18: 905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abernethy AP, Capell WH, Aziz NM, et al. Ethical conduct of palliative care research: enhancing communication between investigators and institutional review boards. J Pain Symptom Manag 2014; 48: 1211–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Casarett D. Ethical considerations in end-of-life care and research. J Palliat Med 2005; 8: s148–s160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duke S, Bennett H. Review: a narrative review of the published ethical debates in palliative care research and an assessment of their adequacy to inform research governance. Palliative Med 2010; 24: 111–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee S, Kristjanson L. Human research ethics committees: issues in palliative care research. Int J Palliat Nurs 2003; 9: 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walker S, Read S. Accessing vulnerable research populations: an experience with gatekeepers of ethical approval. Int J Palliat Nurs 2011; 17: 14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gysels M, Evans CJ, Lewis P, et al. MORECare research methods guidance development: recommendations for ethical issues in palliative and end-of-life care research. Palliative Med 2013; 27: 908–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whitehead PB, Clark RC. Addressing the challenges of conducting research with end-of-life populations in the acute care setting. Appl Nurs Res 2016; 30: 12–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alexander SJ. ‘As long as it helps somebody’: why vulnerable people participate in research. Int J Palliat Nurs 2010; 16: 173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kars MC, van Thiel GJ, van der Graaf R, et al. A systematic review of reasons for gatekeeping in palliative care research. Palliative Med 2016; 30: 533–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fischer DJ, Burgener SC, Kavanaugh K, et al. Conducting research with end-of-life populations: overcoming recruitment challenges when working with clinical agencies. Appl Nurs Res 2012; 25: 258–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moorcraft SY, Marriott C, Peckitt C, et al. Patients’ willingness to participate in clinical trials and their views on aspects of cancer research: results of a prospective patient survey. Trials 2016; 17: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gysels M, Evans C, Higginson I. Patient, caregiver, health professional and researcher views and experiences of participating in research at the end of life: a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12: 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. General Medical Council. Treatment and care towards the end of life: good practice in decision making. Manchester: General Medical Council, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005; 52: 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Evans D, Pearson A. Systematic reviews: gatekeepers of nursing knowledge. J Clin Nurs 2001; 10: 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Caldwell K, Henshaw L, Taylor G. Developing a framework for critiquing health research: an early evaluation. Nurs Educ Today 2011; 31: e1–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Terry W, Olson LG, Ravenscroft P, et al. Hospice patients’ views on research in palliative care. Intern Med J 2006; 36: 406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Head B, Faul A. Research risks and benefits as perceived by persons with a terminal prognosis. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2007; 9: 256–263. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perkins P, Barclay S, Booth S. What are patients’ priorities for palliative care research? Focus group study. Palliative Med 2007; 21: 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bellamy G, Gott M, Frey R. ‘It’s my pleasure?’: the views of palliative care patients about being asked to participate in research. Progr Palliat Care 2011; 19: 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ross C, Cornbleet M. Attitudes of patients and staff to research in a specialist palliative care unit. Palliative Med 2003; 17: 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Siu SWK, Leung PPY, Liu RKY, et al. Patients’ views on failure to gain expected clinical beneficial outcomes from participation in palliative medicine clinical trials. Am J Hosp Palliat Me 2013; 30: 239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. White CD, Hardy JR, Gilshenan KS, et al. Randomised controlled trials of palliative care – a survey of the views of advanced cancer patients and their relatives. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44: 1820–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams CJ, Shuster JL, Jr, Clay OJ, et al. Interest in research participation among hospice patients, caregivers, and ambulatory senior citizens: practical barriers or ethical constraints? J Palliat Med 2006; 9: 968–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pessin H, Galietta M, Nelson CJ, et al. Burden and benefit of psychosocial research at the end of life. J Palliat Med 2008; 11: 627–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gysels M, Shipman C, Higginson IJ. ‘I will do it if it will help others’: motivations among patients taking part in qualitative studies in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manag 2008; 35: 347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coombs MA, Parker R, Devries K. Can qualitative interviews have benefits for participants in end-of-life care research? Eur J Palliat Care 2016; 23: 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Health Medical Research Council. National statement on ethical conduct in human research 2007. Canberra, ACT, Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization. Declaration of Helsinki. B World Health Organ 2001; 79: 373–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Williams A, Selwyn PA, McCorkle R, et al. Application of community-based participatory research methods to a study of complementary medicine interventions at end of life. Compl Health Pract Rev 2005; 10: 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wohleber AM, McKitrick DS, Davis SE. Designing research with hospice and palliative care populations. Am J Hosp Palliat Me 2012; 29: 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fairhall M, Reid K, Vella-Brincat JW, et al. Exploring hospice patients’ views about participating in research. J Pain Symptom Manag 2012; 43: e9–e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abernethy AP, Aziz NM, Basch E, et al. A strategy to advance the evidence base in palliative medicine: formation of a palliative care research cooperative group. J Palliat Med 2010; 13: 1407–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]