Abstract

Objectives

To examine the relation between patients’ illness representations, presented in telephone consultation to out-of-hours (OOH) services, and self-reported degree-of-worry (DOW), as a measure of self-evaluated urgency. If a clear relation is found, incorporating DOW during telephone triage could aid the triage process, potentially increasing patient safety.

Design

A convergent parallel mixed methods design with quantitative data; DOW and qualitative data from recorded telephone consultations. Thematic analysis of the qualitative data was used to explore the content of the quantitatively scaled DOW, using the Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM).

Setting

A convenience sampling of calls to the OOH services in Copenhagen, Denmark, during 3 days was included in the study.

Participants

Calls from adults (≥15 years of age) concerning somatic illness during the data collection period were eligible for inclusion. Calls made on behalf of another person, calls concerning perceived life-threatening illness or calls regarding logistical/practical problems were excluded, resulting in analysis of 180 calls.

Results

All five components of the CSM framework, regardless of DOW, were present in the data. All callers referred to identity and timeline and were least likely to refer to consequence (37%). Through qualitative analysis, themes were defined. Callers with a strong identity, illness duration of less than 24 hours, clear cause and solution for cure/control seemed to present a lower DOW. Callers with a medium identity, illness duration of more than 24 hours and a high consequence seemed to present a higher DOW.

Conclusion

This study suggests a relation between a patient’s illness representation and self-evaluation of urgency. Incorporating a patient’s DOW during telephone triage could aid the triage process in determining urgency and type of healthcare needed, potentially increasing patient safety. Research on patient outcome after DOW-assisted triage is needed before implementation of the DOW scale is recommended.

Keywords: illness representation, degree-of-worry, out-of-hours services, triage

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use of mixed methods approach in this study gave an in-depth insight and enabled a thorough analysis and understanding of the illness representation of patients to an out-of-hours (OOH) service.

Patients’ presentation of their illness representation and reported degree-of-worry (DOW) were obtained at the actual time of seeking help and, therefore, not influenced by recall bias.

DOW was not uniformly obtained at a specific time within the consultation and responses were both spontaneous and/or prompted by the call-handler, which is representative of real-life calls to OOH services.

Use of the NVivo V.11 software and researcher triangulation ensures that the coding of the data is available for independent analysis and less subject to personal bias.

Due to the limited size of the study population, there is a lack of statistical power; however, the results show clear trends and relations, which give direction for future research to strengthen evidence in this new area.

Introduction

Telephone triage within out-of-hours (OOH) service is recognised as a mean to reduce pressure and overcrowding of emergency departments (ED) and OOH clinics.1 It aims to assess the urgency of a patient’s medical condition in order to determine the correct type of healthcare needed, thus ensuring patient safety. However, due to the lack of non-verbal cues in telephone consultations, assessing urgency is more challenging than face-to-face consultations.2 Studies show that the quality of telephone triage improves with communication between patient and health professional being patient centred rather than disease centred3 and that non-normative symptom description and poor communication contribute to under triage.4 Triage tools, for example, computerised decision support systems are used to aid the triage process5; however, these tools focus on medical information and less on psychosocial or affective information.6

Patients’ perception of urgency has previously been examined, comparing ED physicians’ and the patients’ assessment of the severity of symptoms.7 8 These studies found that patients’ perception of urgency can be used as a rough guide to predict the need for hospitalisation.9 Furthermore, it has been suggested that patients expressing a potential need for hospitalisation should be thoroughly examined for possible severe illness.10 Previous studies have also shown that patients’ anxiety or worry about a health threat is a major factor in urgent care decision-making11 12 and that worry is the most important motive for patients contacting OOH services.13 Therefore, the measure of a patient’s worry about an acute health threat reflects the patient’s self-evaluation of urgency. A self-reported verbal 10-point numerical rating scale (NRS) measuring anxiety in patients (1=minimal anxiety to 10=maximal anxiety) has previously been used in several studies in acute care settings.14 The anxiety observed in these patients was regarded as acute in relation to the immediate health threat and not due to an underlying psychiatric disease; thus, the feeling of anxiety in this setting was synonymous to worry.15 This scale has not been validated. However, as anxiety is a subjective symptom, a subjective scoring system was deemed acceptable. A previous study showed that callers to OOH services were able to rate their degree-of-worry (DOW), using a verbal 10-point NRS (1=minimal worry to 10=maximal worry) as a measure of their self-evaluation of urgency. It was also shown that the DOW scale is feasible for use in large-scale studies.16

The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM) by Leventhal17 is a widely recognised theoretical framework, which can be used to describe how a patient cognitively and emotionally addresses a health threat, based on experienced symptoms. The patient’s perception is based on prior experience, personal beliefs, discussions with others and cultural understandings.18 The CSM is a parallel processing model, with one arm representing the cognitive processing aspects and the other arm representing the emotional processing aspects. Together they make up a patient’s illness representation.19 The cognitive arm can be categorised into five components: (1) identity: symptoms or name/label of the health threat, (2) timeline: duration of the health threat, (3) cause: factors that are responsible for the health threat, (4) cure or control: whether the health threat can be cured or controlled and (5) consequence: of the health threat.17 The patients’ understanding of their illness representation influences how they present their health issue to a healthcare provider and this may in turn influence the care they receive.20 In previous studies, it has been shown that the five components of the CSM framework account for a large proportion of the presentations patients make when contacting OOH services21 and serve as an appropriate framework for understanding the worry experiences of primary healthcare patients.22

The aim of this paper is to examine the relation between a patient’s illness representation, as presented in telephone consultation to an OOH service call handler, and the self-reported DOW as a measure of self-evaluated urgency. If there is a relation, incorporating a patient’s DOW as an additional tool in the telephone triage process could aid determination of urgency and type of healthcare needed, potentially increasing patient safety.

Methods

Design

A convergent parallel mixed-methods design with simultaneously collected data was used. This design allows for the transformation of one type of result to another (eg, themes into counts).23 Quantitative data consisted of DOW and qualitative data of recorded telephone consultations. Deductive thematic analysis of the qualitative data was conducted and used to explore the content of the quantitatively scaled DOW, using the framework of the CSM theory.

Setting

The OOH services and the Emergency Medical Services, Copenhagen, the Capital Region of Denmark, are integrated in one organisation and can be reached through two telephone numbers: 112 for life-threatening emergencies and 1813 for acute, non-emergent medical calls. The Medical Helpline 1813 is available from 16:00 to 08:00 on weekdays and around the clock on weekends and holidays. Individuals may also call 1813 for a referral to an emergency department, if they cannot get in touch with their general practitioner (GP) during regular working hours. All access to acute care is pre-assessed by telephone triage. Annually, approximately one million calls are handled by call handlers (nurses/physicians) who triage the caller to self-care, a GP, face-to-face assessment/consultation at a hospital, home visit or direct hospitalisation.24 25

Data collection

A total of 261 callers to the OOH services, The Medical Helpline 1813, during a 3-day time period were approached for inclusion in this study. As a new rating scale was being implemented by the call handlers, it was considered that this was a reasonable length of time. All calls from adults (≥15 years of age) concerning somatic illness were deemed eligible for inclusion. Calls made on behalf of another person, including children (n=16) were excluded, in order to have a study population exclusively describing personal symptoms. Furthermore, calls in which consent was not granted (n=1), calls in which the call handler failed to ask study questions (n=19), calls in which there were technical problems with the call recording (n=33) and repeat callers (n=12) were also excluded. This resulted in a convenience sample of a total of 180 calls. Data were collected for three consecutive days: Wednesday 20 April and Thursday 21 April (16:00 to 22:00) and Friday 22 April (08:00 to 16:00) 2016 (a bank holiday).

Data sources

Data consisted of two parallel strands—the quantitatively scaled DOW and illness representation presented by the callers—both derived from the recorded telephone consultations. Two experienced call handlers were first asked to assess and recommend question phrasing for data collection. All call handlers participated in data collection and received instructions on procedure, inclusion criteria, study focus and voluntary caller participation. Based on the recommendations, call handlers were instructed to ask the following questions in each call: ‘What is your reason for calling in today?’, ‘How long have you been experiencing these symptoms?’ and ‘On a scale from 1 to 10, how worried are you?’. Additional questions were asked at the call handlers’ discretion as they deemed relevant and the caller was invited to participate in the study, giving verbal informed consent. Data were collected throughout the course of the consultation. Calls in which the caller failed to provide a number reflecting their DOW (n=10) were assessed by two researchers and using the intensity verbal descriptors (see table 1, Duncan et al)26 assigned a numeric value (1–10). If not concurrent, a consensus was reached through discussion. The intensity verbal descriptors used describe the intensity of pain and not worry. However, as both pain and worry are subjective, it was felt that in these few cases, the intensity descriptors for pain were an adequate tool.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| DOW | Low DOW: 1–4(%) |

Moderate DOW: 5–6 (%) |

High DOW: 7–10(%) |

| Total study callers | 76 | 39 | 65 |

| Women | 43 (57)* | 24 (62) | 47 (72) |

| Men | 33 (43) | 15 (38) | 18 (28) |

| Age 15–20 years | 4 (5) | 5 (13) | 10 (15) |

| Age 21–40 years | 46 (61) | 19 (49) | 26 (40) |

| Age 41–65 years | 19 (25) | 13 (33) | 21 (32) |

| Age >65 years | 7 (9) | 2 (5) | 8 (12) |

*Percentages of total callers in each DOW group.

DOW, degree-of-worry.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research aim, design, recruitment, conduct and outcome measures in this study were not based on patients’ involvement. The results of this study will not automatically be disseminated to study participants. However, participants can request information regarding this study.

Analysis

The recorded telephone consultations were transcribed in NVivo V.11, and DOW were attached to each call as attributes. According to the information given by the callers, symptom duration (timeline) was categorised into three groups: less than 5 hours, 5–24 hours and more than 24 hours. The remaining qualitative data were deductively coded according to the last four components of the CSM framework, by the main author. For the purpose of simplicity, the results were then subgrouped into: low DOW (DOW 1–4), moderate DOW (DOW 5 and 6) and high DOW (DOW 7–10). Furthermore, the results were compared with two previous studies: Farquharson et al 21 and Lau et al.27

Qualitative data analysis

The qualitative data were created by coding the transcripts deductively according to the four components of the CSM framework (identity, cause, cure/control and consequence), while disregarding the DOW value. For each of the four components, data were clustered and patterns identified. Three themes within each component were derived from these patterns and each theme was recoded, as described by Braun and Clarke.28 The patterns and thereby derived theme definitions were discussed and agreed on with a second researcher, using 50% of the study data. The remaining data were rechecked and recoded if necessary, by the main researcher, according to the agreed theme definitions.

Mixed-methods analysis

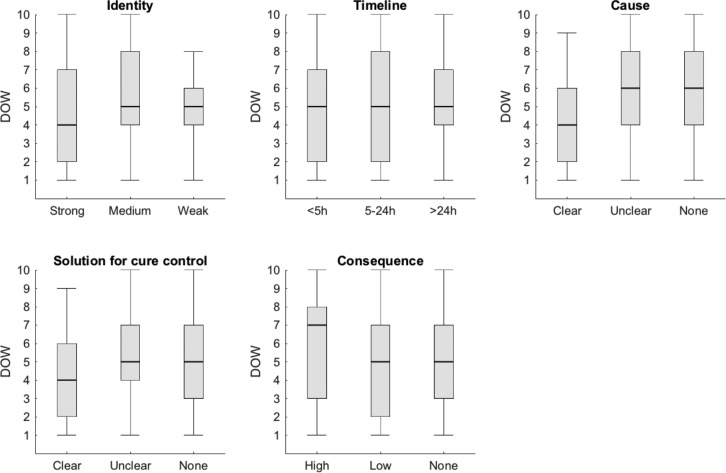

All 180 calls were grouped according to themes in each of the five CSM components and listed according to DOW (1–10). For each theme, the quantiles (Q1–Q3) and median were calculated and a box and whisker plot created.

Results

Participants

A total of 261 callers to the OOH services during the 3-day time period were approached for inclusion. Of these, 81 callers were excluded, based on the exclusion criteria, leaving a total of 180 callers to be included in this study. Due to this limited size of the study population, there is a lack of statistical power. The nature of the calls was as follows: acute illness (n=120), injury (n=37), exacerbation of chronic disease (n=15), other (n=7) and undetermined (n=1), which is representative for calls to the OOH services29 (see table 1).

Quantitative findings according to the CSM framework

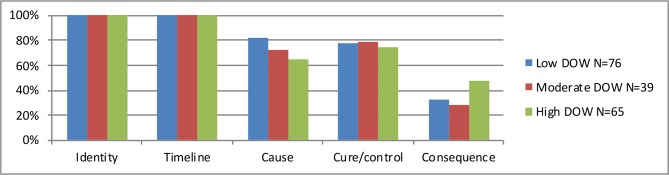

All callers referred to identity as well as duration (timeline) of their symptoms. Callers with a low DOW were more likely to mention a cause for their illness (82%) than other callers, whereas reference to cure/control was similar (78%, 79% and 74%) in all three DOW subgroups. Callers in all three DOW subgroups were least likely to refer to consequence compared with the other four CSM components; however, callers with a high DOW were more likely to refer to a consequence (48%) of their illness than callers with moderate (28%) or low DOW (33%) (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence (%) of components of illness representation in the present study. DOW, degree-of-worry.

Qualitative findings

Identity

Callers’ referrals to the identity of their perceived health threat were divided into three themes. Strong identity: use of a definitive label or diagnosis, reference to a previous identical experience, reference to a known condition and/or expression of certainty (n=56); medium identity: hypothesis of label or diagnosis, reference to a previous similar, but not identical experience and/or expression of near certainty (n=90) and weak identity: no mention of label or diagnosis, no reference to a previous experience, reference to an unknown condition and/or expression of uncertainty (n=34).

Timeline

Fifty-two callers described symptoms which had lasted less than 5 hours, 44 callers described symptoms which had lasted between 5 and 24 hours and 84 callers described symptoms which had lasted more than 24 hours.

Cause

A possible cause of symptoms or illness was reported by 132 callers (73%). The reported causes were divided into the following three themes: clear cause: expression of certainty (n=90); unclear cause: a hypothesis suggested or expression of uncertainty (n=42) and no mention of cause (n=48).

Cure/control

Reference pertaining to a cure or control related to their symptoms or illness was made by 138 callers (77%). These were divided into the following three themes: clear solution for cure/control: specific request for treatment (n=42); unclear solution for cure/control: suggestion for treatment or had attempted self-treatment with little or no effect (n=96) and no mention of cure/control (n=42).

Consequence

Reference to a consequence of their symptoms or illness was made by 67 callers (37%). These were categorised into the following three themes: high consequence: potentially long-term or life-threatening consequences and consequences severely affecting work or social life (n=36); low consequence: short-term consequences, consequences affecting immediate daily life or mildly affecting work or social life (n=31) and no mention of consequence (n=113). (See table 2 for examples of citations of each theme. Citations were chosen to represent the breadth of definition of each theme.)

Table 2.

Thematic analysis of the components of the Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation framework

| Themes | Examples of citations |

| Identity, n=180 (100%) | |

| Strong identity, n=56 (31%) | ‘I have a bladder infection…I have to pee all the time…I also had a UTI last summer…’ ‘I rubbed my eye and now it is red and there is pus… it is an eye infection…I know it goes away, as I have had it before…’ ‘My right big toe is swollen, the area next to the nail is red and infected, I can press pus out…’ |

| Medium identity, n=90 (50%) | ‘I have had genital herpes many times before, but it looks different…maybe it is just a yeast infection…’ ‘…sudden pain after I sneezed…I think I might have punctured a lung or bruised a rib…’ ‘I have a fever and my throat hurts…I think I’m sick…it’s usually a throat infection…’ |

| Weak identity, n=34 (19%) | ‘I suddenly got a severe pain in the left, lower side of my abdomen…I have never tried anything like it before…I cannot figure out why I am in so much pain…’ ‘I have had two attacks of chest pain and cold sweats…I do not usually feel like this…does not feel like pain that I have tried before…I just want to know why…’ ‘I feel really bad; have had a fever for 3–4 days and I’m coughing a lot. Yesterday, I had the shakes and I threw up’ |

| Timeline, n=180 (100%) | |

| <5 hours, n=52 (29%) | ‘…I just fell and cut my forehead and it is bleeding…’ |

| 5–24 hours, n=44 (24%) | …I started feeling sick this morning, but I still decided to go to work |

| >24 hours, n=84 (47%) | …it’s been going on for a few days now… |

| Cause, n=132 (73%) | |

| Clear cause, n=90 (50%) | ‘I fell about eight steps down a staircase and hit my shoulder…’ ‘When I feel like this, it is usually tonsillitis…’ ‘After skating…pain in my leg… muscle strain seems very logical…’ |

| Unclear cause, n=42 (23%) | ‘I think it could be a mixture of stress and bacteria…’ ‘It is not an allergy…my immune system might be a bit affected because I have been travelling a lot…’ ‘It looks like hives, but I do not have any allergies…’ |

| No cause, n=48 (27%) | |

| Cure/control, n=138 (77%) | |

| Clear solution for cure/control, n=42 (23%) | ‘I want to go to the hospital and get stitches…’ ‘I have tried it before; when I got penicillin…I am going to try to convince you to give it me again…’ ‘I have spoken to my husband, who is a doctor, and he believes I need to be seen by an eye specialist…’ |

| Unclear solution for cure/control, n=96 (53%) | ‘I have gotten painkillers from the dentist, but they are not helping; can I take Panodil as well?’ ‘I tried getting in contact with my GP, but no one is picking up the phone…’ ‘Do I have to do anything about it tonight or can it wait until I call my GP tomorrow?’ |

| No solution for cure/control, n=42 (23%) | |

| Consequence, n=67 (37%) | |

| High consequence, n=36 (20%) | ‘I am afraid it could be a blood clot, my mother had that and she lost her entire leg…’ ‘I am pregnant, can it affect the baby?’ ‘I read on Google, that it could be cancer…’ |

| Low consequence, n=31 (17%) | ‘I cannot sleep or eat anything, because of the pain…’ ‘Maybe I cannot go out riding tomorrow…’ ‘I have to travel for work tomorrow…’ |

| No consequence, n=113 (63%) | |

GP, general practitioner; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Mixed methods findings

A clear trend was observed. Study callers with a medium identity seemed to have a higher DOW, whereas callers with a strong identity seemed to have a lower DOW and callers with a weak identity generally seemed to have a moderate DOW. There were more callers with a low DOW who had an illness lasting less than 24 hours than callers who had an illness lasting more than 24 hours. Callers with a clear cause for their illness and a clear solution for cure/control seemed to have a low DOW and, finally, callers who mentioned a high consequence to their illness seemed to have a high DOW (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relation between degree-of-worry (DOW) and the components of the Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation framework.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

Using the five components of the CSM framework, as described by Leventhal,18 our analysis demonstrated that callers presenting their illness to OOH services to a large extent referred to all five components, regardless of their self-evaluated DOW. All callers referred to identity and timeline and callers were least likely to refer to consequence.

Lower DOW seemed to be more present in the group of callers who had a strong illness identity, illness duration of less than 24 hours, a clear cause and a clear solution. Callers who presented a medium or weak illness identity, illness duration of more than 24 hours, an unclear or no cause, unclear or no solution and a perception of high consequence seemed to present a higher DOW.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strength of this study was the use of mixed-methods approach, which gave an in-depth insight and enabled a thorough analysis and understanding of the illness representation of patients to an OOH service. In addition, patients’ illness representation and reported self-evaluation of DOW were obtained in real time, as the callers were seeking help. Findings were, therefore, not influenced by recall bias. DOW was not uniformly obtained at a specific time within the consultation. Therefore, the consultation itself could influence the patient’s DOW and the patient’s DOW could influence the consultation. This, however, is representative of real-life calls to OOH services and how DOW can be used as a potential triage tool. Use of the NVivo V.11 software and researcher triangulation ensures that the coding of the data is available for independent analysis and less subject to personal bias. Due to the short duration of data collection, the size of the study population was limited, resulting in a lack of statistical power. However, irrespective of this limitation, the analyses of the results, using the mixed-methods approach, show a distinct trend and relation between DOW as a measure of patient-evaluated urgency and their illness representation.

Comparison with existing literature

The results of the quantitative data can be compared with the work done by Farquharson et al 21 and Lau et al 27 (see table 3). Participants in both studies and in all three DOW subgroups in the present study mentioned factors pertaining to all five components of the CSM framework. Farquharson et al, however, solely based their data on information that callers volunteered, without call handler prompting, but suggested that it may be necessary for call handlers to prompt remaining components to obtain a comprehensive understanding of patients’ representations of illness. In this study, all information from the caller was coded, including information prompted by the call handler, thus the prevalence in each of the five CSM components was greater compared with those found by Farquharson et al. The method used in this study provides a more complete portrayal of the caller’s illness representation and is more representative of real-life calls to OOH services.

Table 3.

Prevalence (%) of components of illness representation

| Present study | Previous studies | ||||

| Low DOW (n=76) |

Moderate DOW (n=39) |

High DOW (n=65) |

Farquharson et al 21 (n=59) |

Lau et al 27 (n=887) |

|

| Identity | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 96 |

| Timeline | 100 | 100 | 100 | 44 | 49 |

| Cause | 82 | 72 | 65 | 15 | 28 |

| Cure/control | 78 | 79 | 74 | 37 | 32 |

| Consequence | 33 | 28 | 48 | 14 | 33 |

DOW, degree-of-worry.

Relevance of this study: possible implications for healthcare providers and policymakers

This study suggests a relation between patients’ illness representation, as presented telephonically to an OOH services call handler, and their self-evaluation of urgency, defined as DOW. The relation observed, is that DOW is not random, but follows a pattern, depending on patients’ illness representation. This pattern can aid call handlers in understanding patients’ perception of urgency, potentially aiding the triage process.

This is a new area of research and this study gives direction for future research to further strengthen the evidence. Research on coherence between patient DOW and call handlers’, ED and GP physicians’ assessment of urgency, both prospectively and retrospectively will strengthen the basis for potential use of DOW as a triage tool. Incorporating DOW as an additional tool in the telephone triage process could potentially aid in the determination of urgency and the type of healthcare needed, thus increasing patient safety.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SLT and HG-J planned the study and discussed and agreed upon theme definitions in the qualitative analysis. HG-J planned and performed the data collection. SLT extracted and analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. IE and FKL supervised and contributed substantially to the critical revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Data Protection Agency (PVH-2015-004, I-Suite nr: 04330). All participants gave informed consent. The Ethical Committee was consulted but no permission was needed (H-15016323).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data that are not available online can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Würgler MW, Navne LE. Når sygeplejersker visiterer i lægevagten. Copenhagen: Dansk Sundhedsinstitut, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leprohon J, Patel VL. Decision-making strategies for telephone triage in emergency medical services. Med Decis Making 1995;15:240–53. 10.1177/0272989X9501500307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Derkx HP. For your ears only. Quality of telephone triage at out-of-hours centres in the Netherlands. Maastricht: Department of General Practice, University of Maastricht, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gamst-Jensen H, Lippert FK, Egerod I. Under-triage in telephone consultation is related to non-normative symptom description and interpersonal communication: a mixed methods study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2017;25:52 10.1186/s13049-017-0390-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gravsersen DS. Out-of.hours telephone triage by nurses and doctors in Danish acute care settings: a study of quality focusing on communication, safety and efficiency. Aarhus: Research Unit for General Practice, University of Aarhus, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holmström I. Decision aid software programs in telenursing: not used as intended? Experiences of Swedish telenurses. Nurs Health Sci 2007;9:23–8. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gifford MJ, Franaszek JB, Gibson G. Emergency physicians’ and patients’ assessments: urgency of need for medical care. Ann Emerg Med 1980;9:502–7. 10.1016/S0196-0644(80)80187-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hunt RC, DeHart KL, Allison EJ, et al. Patient and physician perception of need for emergency medical care: a prospective and retrospective analysis. Am J Emerg Med 1996;14:635–9. 10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90077-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caterino JM, Holliman CJ, Kunselman AR. Underestimation of case severity by emergency department patients: implications for managed care. Am J Emerg Med 2000;18:254–6. 10.1016/S0735-6757(00)90115-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miyamichi R, Mayumi T, Asaoka M, et al. Evaluating patient self-assessment of health as a predictor of hospital admission in emergency practice: a diagnostic validity study. Emerg Med J 2012;29:570–5. 10.1136/emj.2010.105247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Booker MJ, Simmonds RL, Purdy S. Patients who call emergency ambulances for primary care problems: a qualitative study of the decision-making process. Emerg Med J 2014;31:448–52. 10.1136/emermed-2012-202124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agarwal S, Banerjee J, Baker R, et al. Potentially avoidable emergency department attendance: interview study of patients’ reasons for attendance. Emerg Med J 2012;29 10.1136/emermed-2011-200585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Keizer E, Smits M, Peters Y, et al. Contacts with out-of-hours primary care for nonurgent problems: patients’ beliefs or deficiencies in healthcare? BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:157 10.1186/s12875-015-0376-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fosnocht DE, Swanson ER. Pain and anxiety in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2004;44:S87 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.07.284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Craven P, Cinar O, Madsen T. Patient anxiety may influence the efficacy of ED pain management. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:313–8. 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gamst-Jensen H, Huibers L, Pedersen K, et al. Self-rated worry in acute care telephone triage: a mixed-methods study. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e197–203. 10.3399/bjgp18X695021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger : Rachman S, Contributions to medical psychology. 2 1st edn Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1980:7–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The common-sense model of self-regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med 2016;39:935–46. 10.1007/s10865-016-9782-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hagger MS, Orbell S. A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychol Health 2003;18:141–84. 10.1080/088704403100081321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bugge C, Entwistle VA, Watt IS. The significance for decision-making of information that is not exchanged by patients and health professionals during consultations. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:2065–78. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Farquharson B, Johnston M, Bugge C. How people present symptoms to health services: a theory-based content analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:267–73. 10.3399/bjgp11X567090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laakso V, Niemi PM. Primary health-care patients’ reasons for complaint-related worry and relief. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2013;14:151–63. 10.1017/S1463423612000448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE Publications, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Årsrapportdata. 2016. Copenhagen: Emergency Medical Services Copenhagen, University of Copenhagen; 2015 and 2016. https://www.regionh.dk/om-region-hovedstaden/Den-Praehospitale-Virksomhed/Documents/%C3%85rsrapportdata20152016.pdf (cited 15 Apr 2017).

- 25. Forde I, Nader C, Socha-Dietrich K, et al. Primary care review of Denmark: OECD, 2016. (cited 11 Apr 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duncan GH, Bushnell MC, Lavigne GJ. Comparison of verbal and visual analogue scales for measuring the intensity and unpleasantness of experimental pain. Pain 1989;37:295–303. 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90194-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lau RR, Bernard TM, Hartman KA. Further explorations of common-sense representations of common illnesses. Health Psychol 1989;8:195–219. 10.1037/0278-6133.8.2.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dam PS. 2017. Derfor ringer danskerne 1813. Berlingske. https://www.b.dk/nationalt/derfor-ringer-danskerne-1813 (cited 10 Feb 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.