Abstract

Objectives

Prescription opioid diversion is a significant contributor to the opioid misuse epidemic. We examined the quantity of opioids consumed by emergency department (ED) discharged patients after treatment for an acute pain condition (musculoskeletal, fracture, renal colic, abdominal pain and other), and the percentage of unused opioids available for potential misuse.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Tertiary care trauma centre academic hospital.

Participants

A convenience sample of patients ≥18 years who visited the ED for an acute pain condition (≤2 weeks) and were discharged with an opioid prescription. Patients completed a 14-day paper diary of daily pain medication use. To reduce lost to follow-up, participants also responded to standardised phone interview questions about their previous 14-day pain medication use.

Outcomes

Quantity of morphine 5 mg tablets (or equivalent) prescribed, consumed and unused during a 14-day follow-up. Quantity of opioids to adequately supply 80% of patients for 2 weeks and 95% of patients for the first 3 days was also calculated.

Results

Results for 627 patients were analysed (mean age ±SD: 51±16 years, 48% women). Patients consumed a median of seven tablets of morphine 5 mg (32% of the total prescribed opioids). The quantity of opioids to adequately supply 80% of patients for 2 weeks was 20 tablets of morphine 5 mg for musculoskeletal pain, 30 for fracture, 15 for renal colic or abdominal pain and 20 for other pain conditions. The quantity to adequately supply 95% of patients for the first 3 days was 15 tablets of morphine 5 mg.

Conclusions

Patients discharged from the ED with an acute pain condition consumed a median of fewer than 10 tablets of morphine 5 mg (or equivalent). ED physicians should consider prescribing a smaller quantity of opioids and asking the pharmacist to dispense them in portions to minimise unused opioids.

Trial registration number

NCT02799004; Results.

Keywords: pain management, substance misuse, opioids, acute pain, emergency department

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First large study to prospectively document opioids consumption after an acute pain emergency department (ED) visit.

Use of a 14-day daily diary to document opioid consumption.

Opioid consumption data from a diary or phone interview could be biased by self-report.

The convenience sample from one ED centre and the small sample size for less frequent pain conditions limit the generalisation of our results.

Introduction

In the 1990s, physicians, who were perceived as undertreating pain, changed their practice in order to identify and treat pain more effectively.1 Consequently, emergency department (ED) opioid prescriptions increased significantly in the last two decades.2 3 Meanwhile, opioid misuse (ie, intentional use for non-medical purposes), dependence, overdoses and deaths have increased to epidemic proportions in both the USA and Canada.4–12

Over 10 million US citizens have misused opioids at some point in their life13 and 82 000 Canadians (0.3% of the total population) used prescription opioids non-medically in 2015.14 It is becoming increasingly clear that the availability of unused prescription opioids contributes to misuse.15 For example, 71% of opioid abusers received them through the diversion of prescription opioids (ie, transfer of opioids to someone other than the initial prescription holder), and in 55% of cases, these tablets were the unused medications of friends or family members.13 16

Some US cities and states have formulated ED opioid prescribing guidelines17 18 and developed prescription drug monitoring programmes in hopes of preventing opioid abuse and deaths.19 These recommendations can be summarised as follows: limit the prescription to a 3-day supply (30 tablets maximum), avoid prescribing long-acting opioids and avoid refilling lost or stolen prescriptions.20 However, these guidelines were not based on prospectively collected data, and possibly neglected patient-centred outcomes such as quantity of opioids needed for pain relief.

Prospective surgical studies have shown wide variation in the number of opioid tablets prescribed for the same surgical procedure. Moreover, 58%–92% of the prescribed opioids were unused,15 21–23 and the majority (91%) were not properly stored or discarded,21 leaving them accessible for potential misuse.24 A study on ED opioid prescriptions draw their data from large retrospective25 administrative databases, and did not distinguish between acute and chronic pain in their patient populations. In addition, they were unable to determine whether or not (and how many) opioids were actually consumed.

The main objective of this study was to determine the quantity of opioids consumed by ED patients discharged with an acute pain condition. Based on our pilot study,26 we hypothesised that the quantity of opioids that was consumed during the 2 weeks following an ED visit for acute pain would be fewer than 10 tablets of morphine 5 mg (or equivalent).

Methods

Patient and public involvement

This research originated from the rising death toll from opioids overdose. However, patients or public were not involved in the design or conduct of the study.

Study design and setting

This prospective cohort study was conducted in the ED of a tertiary care level 1 trauma centre academic hospital with an affiliated emergency medicine residency programme and an annual census of approximately 65 000 ED visits (mostly adults). Patients were informed that results of the study could be published and accessible on request.

Selection of participants

Patients aged 18 years and older and treated in the ED from June 2016 to July 2017 were identified by ED physicians 24/7 and then recruited by research nurses. We included patients with an acute pain condition present for less than 2 weeks and discharged from ED with an opioid prescription. A convenience sample was used because we were not able to reliably determine the number of patients missed by ED physicians. We excluded patients who did not speak French or English, were using opioid medication prior to the ED visit, stayed in the ED >48 hours or were suffering from cancer or chronic pain.

Measurements

ED physicians obtained patients’ consent to be contacted by the research nurses to explain the study. Patient demographic information, pain intensity at triage, arrival mode, triage priority and length of ED stay were extracted from our computerised medical system. ED physicians entered the final diagnosis, pain intensity at discharge and which pain medications were prescribed. Patients also received a 14-day diary in which the patient recorded for each day the quantity, the time and the name of all the pain medication consumed. Using preaddressed and prestamped envelopes, these diaries were mailed back after completion. Partly because of the low percentage of the diary returned in our pilot study, 2 weeks post-ED visit, all patients were also interviewed over the phone by a research assistant and responded to five brief questions concerning their pain medication use and current pain intensity. Patients were asked if they had filled their opioid prescription; the quantity of opioids, acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) they had consumed; and whether they had received and filled any new opioid prescriptions in the last 2 weeks. Patients were asked to report their pain on a verbal 11-point Numerical Rating Scale ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 represents ‘no pain at all’ and 10 represents ‘the worst imaginable pain.’ The 2-week follow-up period was chosen because acute pain usually lasts for a short time (days or a few weeks), during which most patients stop taking opioids (88% in our pilot study).26 Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture, a secure, web-based application tool hosted in the hospital.27

Stratification

Because different pain diagnoses have different pain resolution patterns,28 we expected the quantity of opioids required to treat acute pain to vary across pain conditions. The most frequently reported ED pain conditions in the literature and in our pilot study were musculoskeletal, fracture, renal colic and abdominal pain.25 Our pilot data also showed that 85% of patients receiving opioids had one of these four pain conditions.26 For a more pragmatic approach, we included a group of patients with all other uncategorised pain conditions (eg, abscess, burn, tooth pain). These five pain condition categories served as stratification variables for our main outcomes.

Outcomes

The main outcome of this study was the quantity of opioid tablets consumed during the 2-week follow-up period extracted from the paper diary or phone interview (if the diary was not returned). The quantity of opioid tablets cannot be summed as it stands, due to the different potency of different opioids. In addition, dosages vary across opioid types. In order to compare the different opioid forms, each opioid prescription and consumption was transformed into tablets of morphine 5 mg equivalent,29 30 using Berdine and Nesbit’s31 method. A dosage of 3.33 mg of oxycodone and 1.25 mg of hydromorphone were considered equipotent to one morphine 5 mg tablet. The second outcome was the percentage of prescribed opioid tablets that were unused after the 2-week follow-up. The third outcome was determined as the number of morphine 5 mg tablets (or equivalent) that would adequately supply for 2 weeks 80% of patients. Although not supported by any consensus, the 80% threshold was used in a recent surgical study by Hill et al 15 and could provide a reasonable balance between sufficient pain treatments for a large majority of patients while limiting the quantity of unused opioids. Since some US cities and states have formulated ED opioid prescribing recommendations to limit the prescription to a 3-day supply (30 tablets maximum), we extracted from the 14-day diary the quantity of morphine 5 mg tablets (or equivalent) to adequately supply 95% of patients during the first 3 days after ED discharge. To facilitate application of the optimal prescription quantities in a clinical setting, each patient’s morphine 5 mg tablets (or equivalent) consumption was grouped into five tablet bins (0=0; 1 to 5=5, 6 to 10=10; up to a maximum number of five tablets) before threshold calculations.

Analysis

The study sample size was estimated based on our pilot study, where we observed a consumption of 8.8 opioid tablets (SD=10) during a 2-week follow-up.26 To detect a significant difference from the null hypothesis (H0=10) using a Wilcoxon test assuming non-parametric distribution, we had to recruit at least 499 patients to achieve a power of at least 0.80 with an alpha of 0.05 using a one-tailed test (PASS V.11.0; NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA).

The concordance between the 14-day diary and phone interview on the quantity of morphine 5 mg tablets (or equivalent) consumed was assessed with intraclass correlation coefficient. The quantity of consumed pain medication is presented as a median with IQR, since it was not normally distributed. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to assess the effect of sex and age (<65 vs ≥65) on the quantity of morphine 5 mg tablets (or equivalent) consumed. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to compare the quantity of consumed morphine 5 mg tablets (or equivalent) to the null hypothesis (<10 tablets). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the quantity of consumed morphine 5 mg tablets (or equivalent) across pain conditions. Two-by-two comparisons of the quantity of consumed morphine 5 mg tablets (or equivalent) across pain conditions were made using Mann-Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Finally, one-way analysis of variance with Tukey-b post hoc comparison tests were used to compare the percentage of unused opioids across pain conditions. Alpha level was set at 0.05, and all statistics were performed using SPSS V.23 (IBM).

Results

Description of study cohort

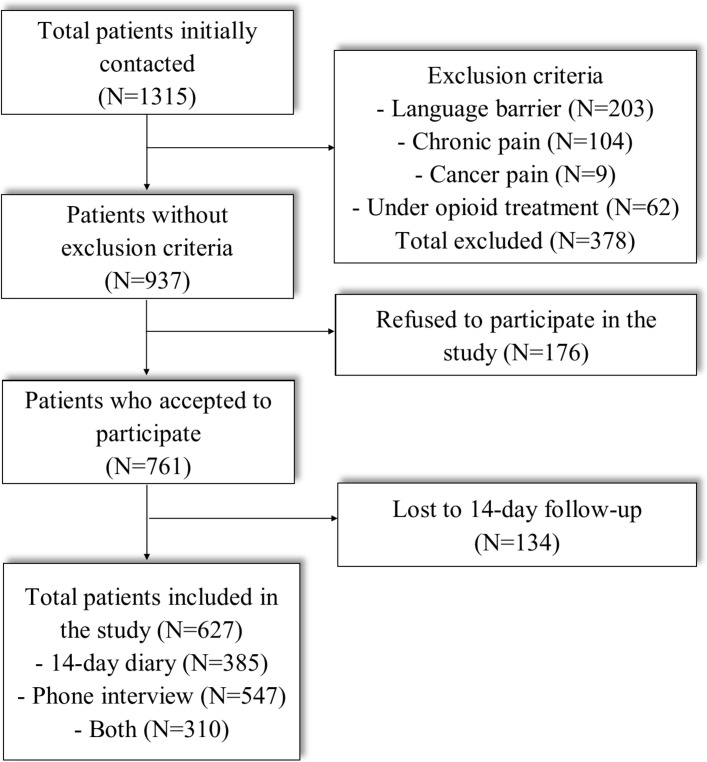

During our 1-year recruitment period, a total of 1315 patients meeting the inclusion criteria were initially contacted. Of these, 29% had exclusion criteria (64% for language barrier, 33% for having chronic pain and 3% for cancer pain), 13% declined to participate and 10% could not be reached for the 14-day follow-up, leaving 627 participants (figure 1). Non-participating and included patients were similar on all baseline characteristics (table 1). Patients’ mean age was 51 (±16) years, 48% were female and mean pain intensity at triage was 7.8, decreasing to 4.8 at ED discharge. Among the 627 participants, 385 (61%) of them returned the 14-day diary, 547 (87%) patients responded to the phone interview and 310 (49%) had completed both assessments. Intraclass correlation coefficient performed on opioids consumed was 0.72 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.77) between the 14-day diary and phone interview which is considered good concordance between both measures.32 Furthermore, the median number of morphine 5 mg tablets consumed was the same (6.7) for both phone interview and the 14-day diary. Therefore, data from the phone interview were used for patients with missing the 14-day diary.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients’ enrolment in the study.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between included and excluded (refused to participate or were lost to the 14-day follow-up) patients

| Baseline characteristics | Included (n=627) | Excluded (n=310) |

| Mean age (±SD) | 51.0 (15.9) | 50.0 (17.8) |

| Female (%) | 47.8 | 49 |

| ED arrival mode (%) | ||

| By himself | 78.6 | 79.9 |

| By ambulance | 21.3 | 20.1 |

| High (level 1 or 2) triage priority (%) | 42.6 | 45.3 |

| Mean pain intensity (0–10 scale) at triage (±SD) | 7.8 (2.0) | 8.0 (1.7) |

| ED treatment section (%) | ||

| Ambulatory | 64.6 | 64.1 |

| On stretcher | 35.4 | 35.9 |

| Type of pain conditions (%) | ||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 44 | 40.3 |

| Fracture | 19.1 | 19.7 |

| Renal colic | 17 | 17.7 |

| Abdominal pain | 6 | 5.2 |

| Other | 13.9 | 17.1 |

| Received a Tylenol prescription at ED discharged (%) | 71.6 | 70.3 |

| Received an NSAIDs prescription at ED discharged (%) | 45.8 | 47.4 |

| Opioid prescription type (%) | ||

| Morphine | 43.6 | 42.7 |

| Oxycodone | 40.5 | 36.9 |

| Hydromorphone | 15.9 | 20.4 |

| Median (IQR) morphine 5 mg equivalent tablets prescription | 30 (28) | 30 (25) |

| Median (IQR) ED stay (hours) | 5.3 (3.6–7.7) | 5.2 (3.7–7.9) |

| Mean (±SD) pain intensity (0–10 scale) at ED discharge | 4.8 (2.9) | 4.7 (2.9) |

ED, emergency department; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Opioid consumption

Almost all patients filled their opioid prescription during the 2-week follow-up period (95%). The median quantity of prescribed morphine 5 mg tablets was 30 (IQR: 28), and similar across all pain condition categories, varying from 24 to 34 tablets of morphine 5 mg (table 2). Variability in the consumed pain medication for the ‘other’ pain condition category was similar to that of the four more common pain condition categories, suggesting that this patient group is comparable. The median quantity of consumed morphine 5 mg tablets was low (7, IQR: 15) compared with the prescribed quantity, and differed significantly from the null hypothesis (H0: <10; p<0.001). The consumed quantity varied significantly across pain condition categories: from 3 tablets of morphine 5 mg for renal colic to 11 tablets morphine 5 mg for fracture (p<0.001). Multiple comparisons showed that patients suffering from renal colic and abdominal pain consumed fewer opioids than those suffering from musculoskeletal pain or fracture (all p<0.05). There was no significant effect of age (<65 vs ≥65) or sex on the quantity of consumed opioids during the 2-week follow-up (p>0.40 for both). Of the whole sample, 79% consumed opioids, 68% used acetaminophen and 45% used NSAIDs.

Table 2.

Pain intensity and pain medication for each pain condition during the 2-week follow-up

| Variables | Musculoskeletal | Fracture | Renal colic | Abdominal | Other | Total |

| No of patients | 280 | 119 | 106 | 37 | 85 | 627 |

| Mean (±SD) pain intensity at ED discharged | 5.6 (2.4) | 5.2 (2.6) | 1.9 (2.7) | 3.7 (3.2) | 5.5 (3.0) | 4.8 (2.9) |

| Mean (±SD) pain intensity at 2 weeks | 2.6 (2.7) | 2.6 (2.9) | 0.5 (1.2) | 1.6 (2.8) | 1.8 (2.6) | 2.0 (2.6) |

| Filled opioid prescription (%) | 95.1 | 90.4 | 99.0 | 97.1 | 91.4 | 94.5 |

| Patients who filled another opioid prescription (n, %) | 22 (7.9) | 10 (8.4) | 3 (2.8) | 2 (5.4) | 5 (5.9) | 42 (6.7) |

| Median (IQR) no of morphine 5 mg prescribed | 30 (28) | 34 (30) | 31 (25) | 30 (19) | 24 (26) | 30 (28) |

| Median (IQR) no of morphine 5 mg consumed | 8 (17) | 11 (20) | 3 (10) | 3 (8) | 6 (14) | 7 (15) |

| Received acetaminophen prescription at discharged (%) | 78.2 | 79.0 | 57.5 | 56.8 | 63.5 | 71.6 |

| Consumed acetaminophen (%) | 73.9 | 87.4 | 49.1 | 48.6 | 52.9 | 67.9 |

| Received NSAIDs prescription at discharged (%) | 49.3 | 28.6 | 64.2 | 40.5 | 37.6 | 45.8 |

| Consumed NSAIDs (%) | 51.8 | 35.3 | 50.9 | 35.1 | 34.1 | 45.1 |

ED, emergency department; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

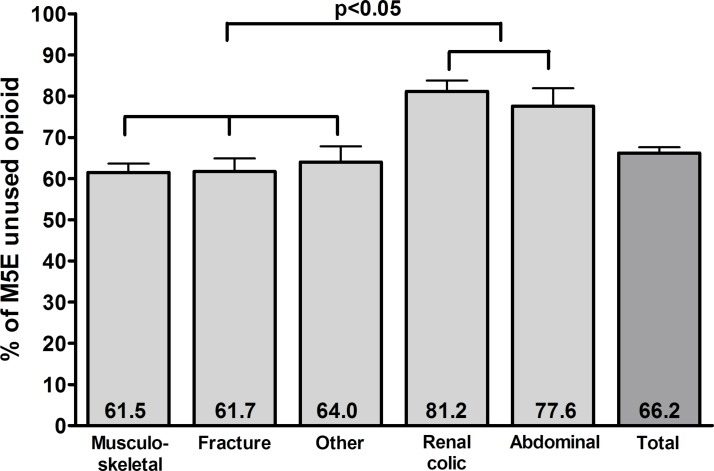

Percentage of unused opioids

Over the course of this study, patients discharged from the ED were prescribed 23 402 tablets of morphine 5 mg, of which 7353 were consumed during the 2-week follow-up period, leaving a total of 16 049 (68%) unused morphine 5 mg tablets. The percentage of unused opioids showed significant differences across pain conditions (p<0.01): patients suffering from renal colic and abdominal pain conditions did not use 81% and 78% of their opioids, respectively, and these were significantly higher than patients suffering from musculoskeletal, fracture or ‘other’ pain condition (62% when averaging three categories; figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of morphine 5 mg equivalent tablets that remained unused after the 2-week follow-up for each pain condition category. Mean±SEM are reported. Brackets indicate the results of the Tukey-b multiple comparisons tests. Renal colic and abdominal pain have higher percentage of unused opioids than each of the three other pain conditions.

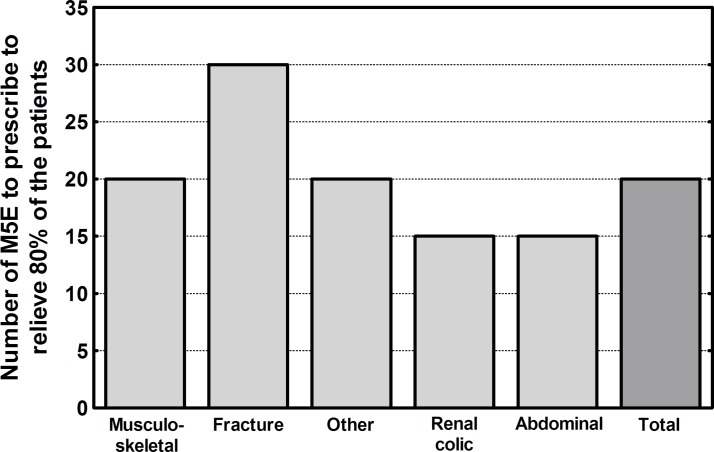

Quantity of opioids to prescribe

Patients’ pain intensity at 2 weeks was low (2.0 average) across all pain conditions. Only a minority of patients (<7%) filled a supplemental opioid prescription, indicating that the initial prescriptions were sufficient to treat pain for 93% of patients during the 2-week period. The quantity of morphine 5 mg tablets to prescribe in order to adequately supply 80% of the patients for 2 weeks was 20 for musculoskeletal pain, 30 for fracture, 15 for renal colic or abdominal pain and 20 for other pain conditions. Patients suffering from renal colic or abdominal pain required only half the quantity compared with patients suffering from fractures (figure 3). The quantity of morphine 5 mg tablets to adequately supply 95% of patients during the first 3 days after ED discharge was 15.

Figure 3.

Number of morphine 5 mg tablets (or equivalent) to prescribe to supply 80% of patients for each pain condition category.

Discussion

This prospective study showed that patients discharged from the ED with an acute pain condition consumed a median of only 7 tablets of morphine 5 mg (or equivalent) but received a median of 30 tablets of morphine 5 mg (or equivalent) prescription, leaving two-thirds of the opioids unused and available for misuse. Furthermore, patients with renal colic or abdominal pain tended to consume fewer opioids during the 2-week follow-up compared with patients with musculoskeletal pain or fractures. We also determined that 20 tablets of morphine 5 mg (or equivalent) could adequately supply 80% of patients while limiting the quantity of unused opioids.

The number of opioids prescribed to patients discharged from the ED with a pain condition in this study was similar to that reported for patients who had upper extremity surgery,22 common general surgical procedures15 and urological surgery.21 This one-size-fits-all approach, which does not take into account the patient’s individual condition, can probably be attributed to the lack of clinical data on opioid consumption.17 18 During the 2-week follow-up, our 68% of opioids left unused is also within the range of percentages observed in surgical studies (58%–92%).15 21–23 The purpose of this overprescribing may be to offset the inconvenience, for both patient and physician, of return visits to the ED or another medical service to obtain another prescription.15 However, these large quantities of unused opioids can be diverted to family and friends, resulting in misuse, dependence and possibly death by overdose.21

Patients suffering from renal colic and abdominal pain needed fewer opioids than those suffering from a fracture or musculoskeletal pain. Rodgers et al also reported differences in opioid consumption between different types of surgery, finding that bone surgery required more opioids than soft-tissue procedures.22 Furthermore, renal colic shows a unique pain resolution pattern: episodic intense pain until the stone is expelled. These results underscore the need for practitioners to adjust their opioid prescriptions to the type of pain condition. If patients in our study were prescribed opioids in order to adequately supply 80% of the patients (20 tablets of morphine 5 mg or equivalent), a total of 10 492 (45%) tablets would not have been available for potential misuse. Since seven tablets of morphine 5 mg (median consumed) would adequately supply 50% of patients, another way of limiting the quantity of unused opioids would require the pharmacist to divide the opioid prescription into portions. Even if repeatable opioid prescriptions are not allowed in most settings, physicians can prescribe a fixed quantity of opioids while instructing the pharmacist to only supply a fraction at a time. For example, a physician could prescribe 15 tablets of morphine 5 mg for a renal colic (and be sure to supply adequately 80% of patients for 2 weeks) and ask the pharmacist to supply only 5 tablets at a time with an expiration date of the prescription in 2 weeks. For physicians with an ED opioid prescribing recommendations to limit the prescription to a 3-day supply (30 tablets maximum), 15 tablets of morphine 5 mg (or equivalent) would adequately supply 95% of patients for that period and limit unused opioids. Opioids consumption could also be reduced if physicians instructed patients to use acetaminophen and/or NSAIDs first to reduce their pain before using opioids.

This trial has certain limitations. The convenience sample from one ED centre and the small sample size for less frequent pain conditions (especially abdominal pain) limit the generalisation of our results. However, patients were recruited 24/7, and consecutive recruitment was limited only by the fact that the investigators could not reliably determine the number of patients missed by ED physicians. It is also possible that other hospitals with different populations or different approach to pain management (eg, adequate dose of non-opioid analgesic first) could change opioid consumption. Moreover, the reasons for the participants to stop consuming opioids were not recorded. Some patients may have restricted their opioid use due to adverse effects, fear of addiction or fear of running out of tablets, among others. There is a need for a multicentre prospective study with larger sample sizes for each pain condition, to determine the impacts on the quantity of unused opioids and incidences of misuse, dependence and opioid overdose.

In summary, patients who are discharged from the ED with an acute pain condition consumed a median of fewer than 10 tablets of morphine 5 mg (or equivalent) during the following 2 weeks, accounting for only one-third of the prescribed opioids, leaving two-thirds of the opioids unused and available for potential misuse. The quantity of opioids to adequately supply 80% of patients for 2 weeks was 20 tablets of morphine 5 mg (or equivalent) for musculoskeletal pain, 30 for fracture, 15 for renal colic or abdominal pain and 20 for other pain conditions. Also, 15 tablets of morphine 5 mg (or equivalent) would adequately supply 95% of patients for the first 3 days. ED physicians should consider prescribing a smaller quantity of opioids and asking the pharmacist to dispense them in portions to minimise unused opioids. These results should be confirmed in a multicentre prospective study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Martin Marquis and Margaret McKyes for their contributions to manuscript revision.

Footnotes

Contributors: RD and J-MC conceived the study and obtained research funding. All authors contributed to the final protocol and data interpretation. JP was responsible for data management and statistical analysis. RD drafted the manuscript, and AC, ÉP, JM, SG, MÉ, GL and JL contributed substantially to its revision. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was supported by the Sacré-Coeur Hospital’s emergency medicine research fund.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: The research nurses obtained informed consent for study participation.

Ethics approval: Approval was obtained from the local institutional ethics review board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Original data set found in the manuscript is available on request to the corresponding author.

Presented at: Part of this study results have been presented at SAEM annual meeting, Orlando, Florida 2017.

References

- 1. Perrone J, Nelson LS, Yealy DM. Choosing analgesics wisely: what we know (and still need to know) about long-term consequences of opioids. Ann Emerg Med 2015;65:500–2. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, et al. Trends in high-dose opioid prescribing in Canada. Can Fam Physician 2014;60:826–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mazer-Amirshahi M, Mullins PM, Rasooly I, et al. Rising opioid prescribing in adult U.S. emergency department visits: 2001-2010. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:236–43. 10.1111/acem.12328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cantrill SV, Brown MD, Carlisle RJ, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the prescribing of opioids for adult patients in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:499–525. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hasegawa K, Espinola JA, Brown DF, et al. Trends in U.S. emergency department visits for opioid overdose, 1993-2010. Pain Med 2014;15:1765–70. 10.1111/pme.12461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Service, U.S. Department Health. Opioid overdoses in the United States. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2012;26:44–7. 10.3109/15360288.2011.653875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers---United States, 1999--2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1487–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dhalla IA, Mamdani MM, Sivilotti ML, et al. Prescribing of opioid analgesics and related mortality before and after the introduction of long-acting oxycodone. CMAJ 2009;181:891–6. 10.1503/cmaj.090784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beaudoin FL, Straube S, Lopez J, et al. Prescription opioid misuse among ED patients discharged with opioids. Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:580–5. 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilsey BL, Fishman SM, Ogden C. Prescription opioid abuse in the emergency department. J Law Med Ethics 2005;33:770–82. 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2005.tb00543.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fischer B, Argento E. Prescription opioid related misuse, harms, diversion and interventions in Canada: a review. Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):Es191–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA 2013;309:657–9. 10.1001/jama.2013.272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manchikanti L, Helm S, Fellows B, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):Es9–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. CCSA, 2017. Canadian centre on substance use and addiction. Prescription opioids. http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/CCSA-Canadian-Drug-Summary-Prescription-Opioids-2017-en.pdf.

- 15. Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, et al. Wide variation and excessive dosage of opioid prescriptions for common general surgical procedures. Ann Surg 2017;265:709–14. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maxwell JC. The prescription drug epidemic in the United States: a perfect storm. Drug Alcohol Rev 2011;30:264–70. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00291.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neven DE, Sabel JC, Howell DN, et al. The development of the Washington State emergency department opioid prescribing guidelines. J Med Toxicol 2012;8:353–9. 10.1007/s13181-012-0267-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Juurlink DN, Dhalla IA, Nelson LS. Improving opioid prescribing: the New York City recommendations. JAMA 2013;309:879–80. 10.1001/jama.2013.1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Poon SJ, Greenwood-Ericksen MB. The opioid prescription epidemic and the role of emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2014;64:490–5. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weiner SG, Perrone J, Nelson LS. Centering the pendulum: the evolution of emergency medicine opioid prescribing guidelines. Ann Emerg Med 2013;62:241–3. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bates C, Laciak R, Southwick A, et al. Overprescription of postoperative narcotics: a look at postoperative pain medication delivery, consumption and disposal in urological practice. J Urol 2011;185:551–5. 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodgers J, Cunningham K, Fitzgerald K, et al. Opioid consumption following outpatient upper extremity surgery. J Hand Surg Am 2012;37:645–50. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, et al. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg 2017;152:1066–71. 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bartels K, Mayes LM, Dingmann C, et al. Opioid use and storage patterns by patients after hospital discharge following surgery. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147972 10.1371/journal.pone.0147972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoppe JA, Nelson LS, Perrone J, et al. Opioid prescribing in a cross section of us emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66:253–9. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quantity of opioid to prescribe for acute pain to limit misuse after emergency department discharge. Orlando, USA: Society for Academic Emergency Medecine, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chapman CR, Fosnocht D, Donaldson GW. Resolution of acute pain following discharge from the emergency department: the acute pain trajectory. J Pain 2012;13:235–41. 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Daoust R, Paquet J, Lavigne G, et al. Impact of age, sex and route of administration on adverse events after opioid treatment in the emergency department: a retrospective study. Pain Res Manag 2015;20:23–8. 10.1155/2015/316275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. O’Neil JT, Wang ML, Kim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of opioid consumption after distal radius fracture repair surgery. Am J Orthop 2017;46:E35–e40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berdine HJ, Nesbit SA. Equianalgesic dosing of opioids. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2006;20:79–84. 10.1080/J354v20n04_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment 1994;6:284–90. 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.