Abstract

Interleukin (IL)-15 is a promising cytokine for cancer immunotherapy as it is a critical factor for the proliferation and activation of natural killer (NK) cells. Previous studies have suggested critical roles of IL-15 in tumor invasion and metastasis. However, the association between IL-15 and liver metastasis of gastric cancer (LMGC) remains unknown. The present study investigated the therapeutic efficacy of recombinant mouse IL-15 (rmIL-15) in murine LMGC models, in which stable green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing MKN45 cells (MKN45-GFP cells) were injected into the spleen parenchyma of mice for liver metastasis. At different treatments (high dose group: 2.5 µg of rmIL-15; low dose group: 0.2 µg of rmIL-15; control group: PBS), it was found that rmIL-15 decreased the formation of liver metastasis sites. Additionally, this treatment lead to improved survival of mice following tumor cell transplantation. Treatment with a high dose of rmIL-15 provided greater therapeutic efficacy by prolonged survival of the mice compared with low dose group and control group. It was found that NK cells isolated from the liver that received the high dose of rmIL-15 showed stronger cytotoxic activity compared with the other two groups on the target cells. These findings hold significant importance for the use of IL-15 as a potential adjuvant/therapeutic for liver metastasis from gastric cancer.

Keywords: interleukin-15, liver metastasis, gastric cancer, cancer immunotherapy, natural killer cell

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide (1). The major causes of mortality are due to local recurrence and distant metastasis (2). Liver metastasis can be found in 5–9% of patients with gastric cancer (3–5). Liver metastasis from gastric cancer (LMGC) has a poor prognosis and there are no effective treatment modalities (6). The present treatment of LMGC includes surgical resection, radiofrequency ablation, hepatic arterial infusion, systemic chemotherapy and targeted therapy (7). However, current treatments are ineffective and the prognosis is poor. Therefore, studies on LMGC remain an important issue.

Interleukin (IL)-15 was co-discovered by two different studies in 1994 and characterized as a T cell growth factor (8,9). Mature human IL-15 is a 14–15 kDa glycoprotein and a member of the four α-helix bundle family of cytokines (10). IL-15 binds to the IL-15-specific high affinity binding protein IL-15Rα and signals through a β chain and a γ chain signaling complex, leading to the recruitment of Janus kinase (JAK) JAK1 by the β chain and activation of JAK3 that is constitutively associated with the γ chain (11). IL-15 performs important roles in immune response, such as stimulating the proliferation of activated T cells (9), B cells (12) and NK cells (13), and shares two receptor subunits with IL-2 (14,15). IL-15 has innate antitumor activity independent of NK and CD8 T cells (16). The direct administration of IL-15 has shown antitumor effects in several preclinical studies of IL-15 immunotherapy in murine tumor models (17,18). Thus far, there have been seven clinical trials initiated to explore anticancer vaccination or immunotherapy with IL-15 (19).

According to recent advances, IL-15 is a promising cytokine for cancer immunotherapy, however the association between IL-15 and LMGC remains unknown. Therefore, the present study used a LMGC mouse model to investigate the role of IL-15 in liver metastasis. Using different doses for treatment, the role of IL-15 in LMGC was investigated.

Materials and methods

Cell line

The gastric cancer MKN45 cell line and YAC-1, a mouse lymphoma cell line sensitive to NK cells, were obtained from Shanghai Institute for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, and maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (all supplied by Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Stable green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing MKN45 cells (MKN45-GFP) were maintained in the same culture as the MKN45 cells.

Mice

Female BALB/c nu/nu mice (n=54) and BALB/c mice (n=18), 4–6-week-old and 15–20 g, were purchased from Chinese Academy of Sciences. All mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Animal Facility of Fudan University (Shanghai, China). Mice were fed a standard laboratory chow, given water as required and subjected to an equal 12-h light/dark cycle in accordance with institutional guidelines. These experiments were approved by the Shanghai Medical Experimental Animal Care Commission.

Liver metastasis model and treatment procedure

A total of 1×106 (0.2 ml) MKN45-GFP cells were re-suspended in sterile PBS and injected into the spleen parenchyma of all mice following anesthesia using 1% pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg). The spleen was removed 5 min following tumor injection to prevent spleen tumor formation, so that metastatic lesions developed only in the liver.

All BALB/c nu/nu mice (n=36) were randomly assigned to receive the following treatments: Low dose group (n=12), 0.2 µg rmIL-15 in 0.1 ml saline; high dose group (n=12), 2.5 µg rmIL-15 in 0.1 ml saline; control group (same volume of PBS, 0.1 ml, n=12). All the mice were treated 5 times a week for 3 weeks. On day 28, 6 mice from each group were sacrificed, their livers were harvested, the number of liver metastases nodules was counted and liver weight was measured. The rest of the mice (3 groups, n=6/group) were monitored for survival according to the different therapies (0.2 µg rmIL-15, 2.5 µg rmIL-15 or PBS).

Assessment of liver tissue

The livers were excised and fixed with 10% buffered formalin for 24 h at 4°C and were paraffin-embedded. Stable GFP-expressing MKN45-GFP cells were injected into the spleen parenchyma Tissues were cut into 5 µm thick serial sections for fluorescent imaging. The number of liver metastatic nodules in each tissue section were evaluated by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

ELISA of cytokines

Blood samples (1 ml, n=6/group) were obtained from the tail vein of mice on day 12. Blood was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the serum was extracted and the extracted serum was stored at −80°C. The serum IL-15 and interferon (IFN)-γ concentrations were measured by ELISA with the use of Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), and the ELISA was performed as indicated in the manufacturer's protocol. Quantifications were conducted in triplicate.

Flow cytometric analysis

Selective NK depletion was confirmed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) on day 21. Blocking was performed using FcR Blocking Reagent mouse (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) at 4°C for 30 min. The mouse splenocytes were incubated with saturating amounts (1 µg/106 cells) of phycoerythrin conjugated anti-mouse cluster of differentiation (CD) 49b monoclonal antibody (mAb; 1:100; cat. no., 553858; BD Biosciences) and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse CD3 mAb (1:100; cat. no. 555274; BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C. Following incubation, cells were washed once in PBS (400 × g for 15 min at 4°C) and analyzed for fluorescence intensity using the FACS Calibur cytometer Data were processed using FlowJo software version 7.6 (BD Biosciences).

Cytotoxicity assay

Effector cells from each of the treatment groups were cultured with 1×104 MKN45 target cells/well in triplicate at varying effector to target cell ratios, and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Cytotoxic activity was measured by lactate dehydrogenase release. The percentage cytotoxicity was calculated as 100× [(experimental release)-(effector spontaneous release)-(target spontaneous release)]/[(target maximum release)-(target spontaneous release)].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 19.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The statistical significance of differences in survival of the mice in different groups was determined by the log-rank test. Statistical differences in the data were evaluated by a Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance as appropriate, the post-hoc test used was the least significant difference test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

IL-15 treatment leads to decreased liver metastasis

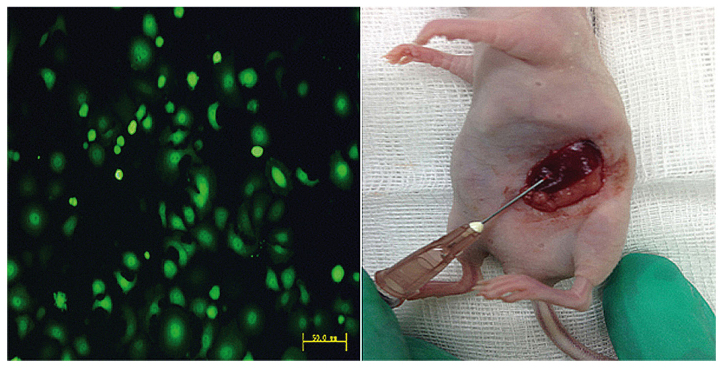

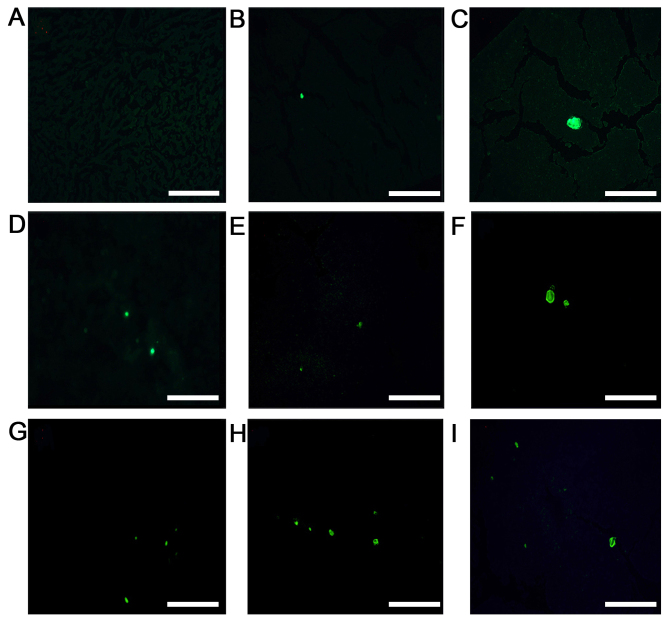

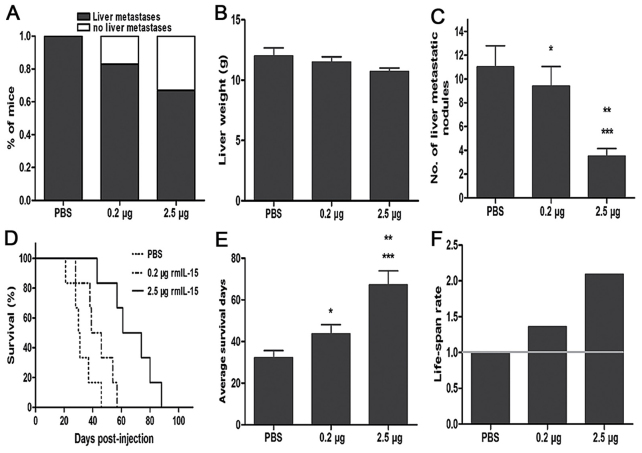

Nude mice were treated with gastric carcinoma MKN45-GFP cells into the spleen parenchyma (Fig. 1). rmIL-15 was intraperitoneally administered 5 times a week for 3 weeks at 2.5 µg (high dose) or 0.2 µg (low dose) per injection. PBS was used as the control group. The development of liver metastases was assessed in detection of liver metastasis by fluorescent microscopy (Fig. 2). The tumor appearance, liver weight and number of liver metastasis nodules were monitored. rmIL-15 was found to inhibit metastatic dissemination of MKN45-GFP cells: 66.7% (4/6) and 83.3% (5/6) of mice administered high or low dose rmIL-15 developed liver metastases, respectively, in contrast to 100% (6/6) among PBS-treated mice (P>0.05; Fig. 3A). Liver weight was not significantly increased in mice treated with rmIL-15 compared with PBS-treated mice (P>0.05; Fig. 3B). In addition, high dose rmIL-15 also led to a significant reduction in the number of liver metastasis nodules compared with low dose treatment (P<0.05) and high dose rmIL-15 led to a decrease in the number of liver metastasis nodules compared with that observed in the PBS-treated group (P<0.05) (Fig. 3C).

Figure 1.

Establishing a mouse model of liver metastasis from gastric cancer. Representative fluorescence image of MKN45-GFP and representative image of spleen during injection of 1×106/0.2 ml of MKN45-GFP cells into the spleen parenchyma of nude mice. MKN45-GFP cells, stable green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing MKN45 cells (scale bar, 50 µm).

Figure 2.

Representative fluorescence images of low-dose, high-dose and control groups (scale bar, 20 µm). MKN45-green fluorescent protein cells were injected into the spleen parenchyma and the livers were cut into 5-µm thick serial sections for fluorescence imaging. Female BALB/c nu/nu mice aged 4–6 weeks old were assigned randomly into a low-dose group (0.2 µg rmIL-15), high-dose group (2.5 µg rmIL-15) and control group (PBS), with 6 mice/group. All mice were treated five times/week for 3 weeks. On day 28, 6 mice/group were sacrificed. (A-C) Representative fluorescence images of the high-dose group, (D-F) Representative fluorescence images of the low dose group. (G-I) Representative fluorescence images of the control group. rmIL-15, recombinant mouse interleukin-15.

Figure 3.

Liver metastasis and survival of nude mice. Mice were inoculated with 1×106 MKN45 cells into the spleen parenchyma. After 24 h, they were divided into three groups: Control (PBS treatment), 0.2 µg rmIL-15 and 2.5 µg rmIL-15. At day 28, metastasis nodules on the livers were counted. The rest of the mice were monitored daily until mortality. (A) 66.7% (4/6) and 83.3% (5/6) of mice given high or low dose rmIL-15 developed liver metastases, respectively, in contrast to 100% (6/6) among PBS-treated mice. (B) Mean liver weight of the three experimental groups; no significant difference among three groups (P>0.05). (C) rmIL-15 treatment caused a decrease in the number of liver metastasis nodules compared with PBS treatment, (P<0.05), and the number of liver metastasis nodules of the high dose rmIL-15 group was significantly less than the low dose group (P<0.05). (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves, (E) average survival and (F) increased life-span rate in the liver metastasis model confirmed an association between 2.5 µg rmIL-15 therapy and longer survival time. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. All statistics were calculated by the long-rank test (*P>0.05 vs. control, **P<0.05 vs. 0.2 µg, ***P<0.01 vs. control). rmIL-15, recombinant mouse interleukin-15.

IL-15 treatment increases the survival rate of nude mice

In the survival assay, mice were monitored daily until mortality occurred. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed that the probability of survival was significantly higher for mice treated with the high dose rmIL-15 therapy (P<0.01 vs. low dose; P<0.005 vs. control; Fig. 3D). Mice treated with PBS survived a median of 32 days (range, 21–46 days). Animals treated with low dose rmIL-15 did not show a survival advantage over animals treated with PBS (median survival, 44 days; range, 28–57 days; P>0.05). Mice receiving high dose rmIL-15 (median survival, 59 days; range, 43–88 days) demonstrated a significant prolongation of survival when compared with the PBS-treated group (Fig. 3E). Lifespan rate was calculated as the ratio of treated/control group. High dose rmIL-15 therapy led to an increased life-span rate of (109%), whereas low dose rmIL-15 improved by only (36%) (Fig. 3F).

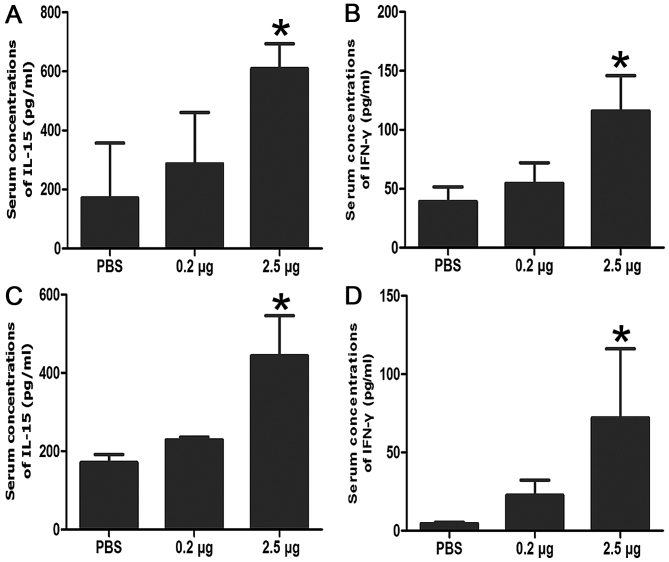

IL-15 treatment increases the concentration of IFN-γ in the bloodstream

Blood samples were obtained from the tail vein of mice on day 12. IL-15 and IFN-γ secretion was measured. Mice treated with rmIL-15 demonstrated an increased IFN-γ secretion compared with the PBS control group in nude mice as well as the Balb/c mouse model (P<0.05; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The serum concentrations of IL-15 and IFN-γ with different treatments indicated that IL-15 induced IFN-γ secretion both in nude mice and Balb/c mice. (A) Serum concentrations of IL-15 in nude mice, *P<0.05 vs. control. (B) Serum concentrations of IL-15 in nude mice, *P<0.05 vs. control. (C) Serum concentrations of IL-15 in Balb/c mice, *P<0.05 vs. control. (D) Serum concentrations of IFN-γ in Balb/c mice, *P<0.05 vs. control. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. IL-15, interleukin-15; IFN-γ, interferon-γ.

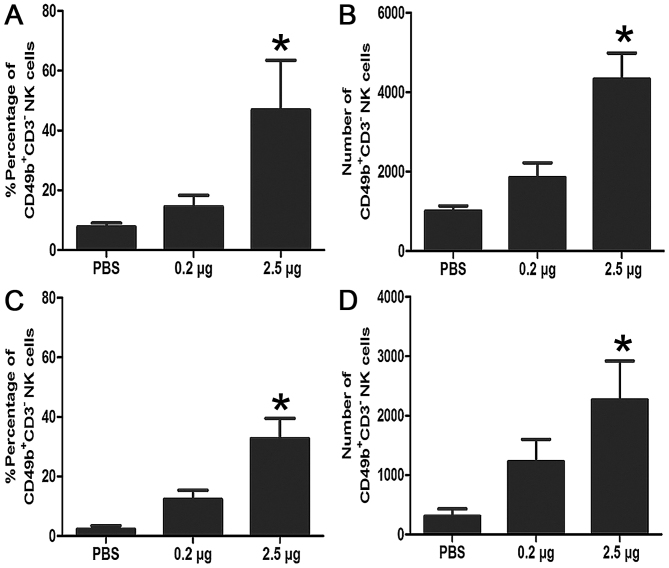

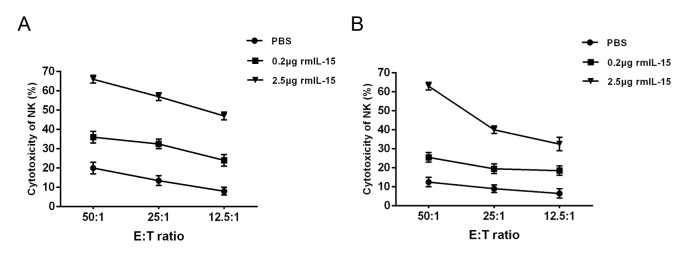

IL-15 induces NK cell proliferation and lytic activity

The target cells used were YAC-1 and MKN45 in NK cell assays The studies showed that treatment with either high dose mIL-15 or low dose mIL-15 had greater therapeutic efficacy. NK cells are involved in the antitumor action mediated by mIL-15 in nude mice or Balb/c mice model. It was revealed that mIL-15 treatment induced NK cell proliferation (Fig. 5) and increased the cytotoxic activity of NK cells (Fig. 6) in nude mice and Balb/c mice.

Figure 5.

NK-mediated cytotoxicity of liver isolated from the tumor-bearing mice. Livers were isolated and incubated with MKN45 cells, or NK cell-sensitive YAC-1 in nude mice or Balb/c mice. (A) Percentage of CD49b+CD3−NK cells in nude mice, *P<0.05 vs. control. (B) Number of CD49b+CD3−NK cells in nude mice, *P<0.05 vs. control. (C) Percentage of CD49b+CD3−NK cells in Balb/c mice, *P<0.05 vs. control. (D) Number of CD49b+CD3−NK cells in Balb/c mice, *P<0.05 vs. control. NK, natural killer; CD3, cluster of differentiation 3; CD49b, cluster of differentiation 49b; rmIL-15, recombinant mouse interleukin-15.

Figure 6.

NK-mediated cytotoxicity of liver isolated from the tumor-bearing mice. Livers were isolated and incubated with NK cell-sensitive YAC-1 in (A) nude mice or (B) Balb/c mice, respectively. Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Difference between the control and low dose rmIL-15 group was significant, also between the control and high dose rmIL-15 group for NK activities (*P<0.05). NK, natural killer; rmIL-15, recombinant mouse interleukin-15.

Discussion

In 1889, Paget (20) found that the organ distribution of metastases is not a matter of chance and first noted that metastasis from specific tumor types grew in select secondary organ sites. Paget suggested that metastases develop only when the seed (certain tumor cells with metastatic ability) and the soil (organs providing growth advantage to the seeds) are compatible (20). Paget's seed and soil hypothesis stated that cancer metastasis requires permissive interactions between tumor cells and secondary organ microenvironments. IL-15 is a pleiotropic cytokine sharing structural homology and receptor components with IL-2 (21,22). IL-2 has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and malignant melanoma (23,24). However, its toxicity at high doses as well as its ability to promote activation-induced cell death and expansion of T regulatory cells had limited its contemplated use in cancer treatment (25). In the past, the antitumor effect of IL-15 has been widely reported (26–28), and it has been recognized as a more promising cytokine than IL-2, with the potential for application in tumor therapy, since IL-15 is more potent than IL-2 in tumor therapy with greater therapeutic index (29).

In recent years, several studies have provided evidence that IL-15 administration serves an important role in tumor therapy (28,30). Zhang et al (31) found IL-15 combined with an anti-CD40 antibody provides enhanced therapeutic efficacy for murine models of colon cancer, combination of mIL-15 with the anti-CD40 antibody enhanced the cytotoxic activity of NK cells and increased the total NK cell numbers. Yu et al (32) showed that IL-15 treatment resulted in a significant prolongation of survival in a metastatic murine colon carcinoma CT26 model. The data reported in their study showed enhancement of immune responses leading to increased antitumor activity.

Liver metastasis contributed to the major cause of mortality in patients with gastric cancer at advanced stages (3,6,33). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the role of IL-15 in LMGC. The present study has revealed that the presence of IL-15 could prolong the survival time of nude mice and prevent liver metastasis from gastric cancer. Furthermore, it was found that IL-15 enhances the cell activity of NK cells in nude mice or immunogenicity mice. Evidence exists that IL-15 serves a key role in murine NK cell homeostasis: NK cells are absent in IL-15 knockout (34) and IL-15Rα knockout mice (35). NK cells develop from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors, first in the fetal liver, then in bone marrow and lymph nodes under the effect of the cytokine IL-15 (36). The liver may have unique precursors for memory NK cells, which are developmentally distinct from NK cells derived from bone marrow (37).

The present study showed that changes in the immune microenvironment of the liver can affect tumor metastasis and antitumor properties. The antitumor effects of IL-15 observed in the present study are likely underestimated, since the experimental systems used here excluded the effect of T cells. IL-15 is also important for NK cell activation as IFN-γ and Granzyme B expression in NK cells is induced by IL-15, and deficient in the absence of IL-15 (38,39). IL-15 activated NK cells through the IL-15/IL-15Rα complex trans-presentation (40). For the soil, the mechanism of liver metastasis from gastric cancer was investigated from the perspective of the target organ immune microenvironment. Target organ microenvironment, particularly the immune microenvironment, performs an important role in tumor metastasis (41,42). The immunotherapy of cancer has made significant strides in the past few years due to improved understanding of the underlying principles of tumor biology and immunology (43,44). NK cells are critical innate effectors with direct killing and regulatory roles, shown to be important antitumor effectors, exhibiting direct cytotoxicity and more regulatory, cytokine-mediated effects (45). Presumably, at least some of the aforementioned mechanisms could be responsible for the development of cytotoxic effectors against tumor cells in mice treated with IL-15.

In conclusion, IL-15 was found to exhibit a significant therapeutic effect on liver metastasis from gastric cancer by enhancing NK cell activity in a murine model. The findings of the present study provide the scientific basis, and it is expected that administration of IL-15 for clinical treatment of patients with gastric cancer liver metastasis will be seen in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81272726), the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (grant no. 20110071120097) and the Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau Research Project (grant no. 20114174).

Availability of data and materials

All data that were generated or analyzed in this study are included in this manuscript.

Authors' contributions

WW, HH and JJ conceived and designed the study. FD, ZC and ZL conducted the experiments. XL and HC performed the statistical analysis. YZ interpreted the statistical analysis, and reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

These experiments were approved by the Shanghai Medical Experimental Animal Care Commission.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2012: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:129–142. doi: 10.3322/caac.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasako M, Sakuramoto S, Katai H, Kinoshita T, Furukawa H, Yamaguchi T, Nashimoto A, Fujii M, Nakajima T, Ohashi Y. Five-year outcomes of a randomized phase III trial comparing adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 versus surgery alone in stage II or III gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4387–4393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakamoto Y, Ohyama S, Yamamoto J, Yamada K, Seki M, Ohta K, Kokudo N, Yamaguchi T, Muto T, Makuuchi M. Surgical resection of liver metastases of gastric cancer: An analysis of a 17-year experience with 22 patients. Surgery. 2003;133:507–511. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okuyama K, Isono K, Juan IK, Onoda S, Ochiai T, Yamamoto Y, Koide Y, Satoh H. Evaluation of treatment for gastric cancer with liver metastasis. Cancer. 1985;55:2498–2505. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850515)55:10<2498::AID-CNCR2820551032>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Angelica M, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Turnbull AD, Bains M, Karpeh MS. Patterns of initial recurrence in completely resected gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240:808–816. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143245.28656.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakamoto Y, Sano T, Shimada K, Esaki M, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Katai H, Kosuge T, Sasako M. Favorable indications for hepatectomy in patients with liver metastasis from gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:534–539. doi: 10.1002/jso.20739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kakeji Y, Morita M, Maehara Y. Strategies for treating liver metastasis from gastric cancer. Surg Today. 2010;40:287–294. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burton JD, Bamford RN, Peters C, Grant AJ, Kurys G, Goldman CK, Brennan J, Roessler E, Waldmann TA. A lymphokine, provisionally designated interleukin T and produced by a human adult T-cell leukemia line, stimulates T-cell proliferation and the induction of lymphokine activated killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4935–4939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grabstein KH, Eisenman J, Shanebeck K, Rauch C, Srinivasan S, Fung V, Beers C, Richardson J, Schoenborn MA, Ahdieh M, et al. Cloning of a T cell growth factor that interacts with the beta chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Science. 1994;264:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.8178155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perera LP. Interleukin 15: Its role in inflammation and immunity. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2000;48:457–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Sabatino A, Calarota SA, Vidali F, Macdonald TT, Corazza GR. Role of IL-15 in immune-mediated andinfectious diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armitage RJ, Macduff BM, Eisenman J, Paxton R, Grabstein KH. IL-15 has stimulatory activityfor the induction of B cell proliferation and differentiation. J Immunol. 1995;154:483–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carson WE, Fehniger TA, Haldar S, Eckhert K, Lindemann MJ, Lai CF, Croce CM, Baumann H, Caligiuri MA. Apotential role for interleukin-15 in the regulation of human natural killer cell survival. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:937–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI119258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Santo JP, Kuhn R, Muller W. Common cytokine receptor chain (c)-dependent cytokines: Understanding in vivo functions by gene targeting. Immunol Rev. 1995;148:19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1995.tb00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asao H, Okuyama C, Kumaki S, Ishii N, Tsuchiya S, Foster D, Sugamura K. Cutting edge: The common -chain is an indispensable subunit of the IL-21 receptor complex. J Immunol. 2001;167:1–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies E, Reid S, Medina MF, Lichty B, Ashkar AA. IL-15 has innate anti-tumor activity independent of NK and CD8 T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:529–536. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0909648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh S, Berzofsky JA, Burke DS, Waldmann TA, Perera LP. Coadministration of HIV vaccine vectors with vaccinia viruses expressing IL-15 but not IL-2 induces long-lasting cellular immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3392–3397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630592100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munger W, DeJoy SQ, Jeyaseelan R, Sr, Torley LW, Grabstein KH, Eisenmann J, Paxton R, Cox T, Wick MM, Kerwar SS. Studies evaluating the antitumor activity and toxicity of interleukin-15, a new T cell growth factor: Comparison with interleukin-2. Cell Immunol. 1995;165:289–293. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steel JC, Waldmann TA, Morris JC. Interleukin-15 biology and its therapeutic implications in cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1889;8:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giri JG, Ahdieh M, Eisenman J, Shanebeck K, Grabstein K, Kumaki S, Namen A, Park LS, Cosman D, Anderson D. Utilization of the beta and gamma chains of the IL-2 receptor by the novel cytokine IL-15. EMBO J. 1994;13:2822–2830. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D¨obbeling U, Dummer R, Laine E, Potoczna N, Qin JZ, Burg G. Interleukin-15 is an autocrine/paracrine viability factor for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells. Blood. 1998;92:252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heemskerk B, Liu K, Dudley ME, Johnson LA, Kaiser A, Downey S, Zheng Z, Shelton TE, Matsuda K, Robbins PF, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with melanoma, using tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes genetically engineered to secrete interleukin-2. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:496–510. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klapper JA, Downey SG, Smith FO, Yang JC, Hughes MS, Kammula US, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Steinberg SM, Rosenberg S. High-dose interleukin-2 for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A retrospective analysis of response and survival in patients treated in the surgery branch at the National Cancer Institute between 1986 and 2006. Cancer. 2008;113:293–301. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz RN, Stover L, Dutcher J. Managing toxicities of high-dose interleukin-2. Oncology (Williston Park) 2002;16(11 Suppl 13):S11–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheng YQ, Cui LX, He W, Xue L, Ba DN. Antitumor effects of human IL-15 gene modified lung cancer cell line. Chin J Cancer Res. 1997;9:240–244. doi: 10.1007/BF02974966. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia H, Luo LM, Wen JX, Tong WC. Inhibitory effects of recombinant human endostatin on growth and metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma LA795 in mice. Ai Zheng. 2002;21:1197–1202. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lasek W, Basak G, Switaj T, Jakubowska AB, Wysocki PJ, Mackiewicz A, Drela N, Jalili A, Kamiński R, Kozar K, Jakóbisiak M. Complete tumor regressions induced by vaccination with IL-12 gene-transduced tumor cells in combination with IL-15 in a melanoma model in mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0449-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabbagh L, Snell LM, Watts TH. TNF family ligands define niches for T cell memory. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapoval AI, Fuller JA, Kremlev SG, Kamdar SJ, Evans R. Combination chemotherapy and IL-15 administration induce permanent tumor regression in a mouse lung tumor model: NK and T cell-mediated effects antagonized by B cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:6977–6984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang M, Yao Z, Dubois S, Ju W, Müller JR, Waldmann TA. Waldmann: Interleukin-15 combined with an anti-CD40 antibody provides enhanced therapeutic efficacy for murine models of colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7513–7518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902637106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu P, Steel JC, Zhang M, Morris JC, Waldmann TA. Simultaneous blockade of multiple immune system inhibitory checkpoints enhances antitumor activity mediated by interleukin-15 in a murine metastatic colon carcinoma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6019–6028. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okano K, Maeba T, Ishimura K, Karasawa Y, Goda F, Wakabayashi H, Usuki H, Maeta H. Hepatic resection for metastatic tumors from gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2002;235:86–91. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200201000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, Butz EA, Viney JL, Embers M, Matsuki N, Charrier K, Sedger L, Willis CR, et al. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:771–780. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lodolce JP, Boone DL, Chai S, Swain RE, Dassopoulos T, Trettin S, Ma A. IL-15 receptor maintains lymphoid homeostasis by supporting lymphocyte homing and proliferation. Immunity. 1998;9:669–676. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becknell B, Caligiuri MA. Interleukin-2, interleukin-15, and their roles in human natural killer cells. Adv Immunol. 2005;86:209–239. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)86006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang X, Chen Y, Peng H, Tian Z. Memory NK cells: Why do they reside in the liver? Cell Mol Immunol. 2013;10:196–201. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2013.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minagawa M, Watanabe H, Miyaji C, Tomiyama K, Shimura H, Ito A, Ito M, Domen J, Weissman IL, Kawai K. Enforced expression of Bcl-2 restores the number of NK cells, but does not rescue the impaired development of NKTcells or intraepithelial lymphocytes, in IL-2/IL-15 receptor beta-chain-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:4153–4160. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koka R, Burkett P, Chien M, Chai S, Boone DL, Ma A. Cutting edge: Murine dendritic cells require IL-15Ralpha to prime NK cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:3594–3598. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castillo EF, Schluns KS. Regulating the Immune system via IL-15 Transpresentation. Cytokine. 2012;59:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye QH, Jia HL, He P, Zanetti KA, Kammula US, Chen Y, Qin LX, Tang ZY, Wang XW. Prediction of venous metastases, recurrence, and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma based on a unique immune response signature of the liver microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muller AJ, Scherle PA. Targeting the mechanisms of tumoral immune tolerance with small-molecule inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:613–625. doi: 10.1038/nrc1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammerstrom AE, Cauley DH, Atkinson BJ, Sharma P. Cancer immunotherapy: Sipuleucel-T and beyond. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:813–828. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.8.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheson BD, Leonard JP. Monoclonal antibody therapy for B-cell non-Hodgkin 7S lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:613–626. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ljunggren HG, Malmberg KJ. Prospects for the use of NK cells in immunotherapy of human cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:329–339. doi: 10.1038/nri2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data that were generated or analyzed in this study are included in this manuscript.