Abstract

Spindle cell melanoma (SCM) is a rare morphological subtype of melanoma, which is relatively uncharacterized. The aim of the present study was to investigate the incidence of SCM, its general demographics, basic clinico-pathologic features, treatment outcomes and disease-specific prognostic factors. SCM cases were sampled from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program (1973–2017). A total of 4761 SCM cases were identified, with a median age of 66 years. The female:male ratio was 0.62:1. Statistically significant overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) rate differences were identified depending on age, sex, ethnicity, tumor location, T stage, N stage, M stage, pathological grade, AJCC stage, SEER stages and surgical treatment (P<0.05). Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that age >66 years, T3+T4 stage disease, positive N stage and SEER historic stage of regional and distant metastasis tumor were associated with poor DSS and OS rates. In summary, SCM was most common in Caucasian people of 60~80 years of age with a predominance in males. Patient's age, ethnicity, T stage, N stage, and SEER historic stage were identified as independent prognostic factors of SCM in terms of DSS and OS.

Keywords: spindle cell melanoma, incidence, prognostic factor, the surveillance, epidemiology and end results

Introduction

Spindle cell melanoma (SCM) is a rare subtype of malignant melanoma composed of spindled neoplastic cells arranged in sheets and fascicles (1). The diagnosis of SCM is challenging, as SCM may occur anywhere on the body and frequently mimics amelanotic lesions, including scarring and inflammation (2–4). Histologically, cytologic features of SCM are indistinct and often confused with those of other epithelial neoplasms, including sarcomas and lymphomas (5–8). Immunohistochemistry is a helpful tool in distinguishing SCM from other sarcomas and carcinomas (9,10). However, diagnosis remains a challenge as a number of sarcomas share some morphological and immunohistochemical features with SCM (5,11). Differentiation of SCM from desmoplastic melanoma is difficult because both melanomas are characterized by atypical, spindled, malignant melanocytes. However, the size of spindle cell collagen areas and the immunohistochemical markers, S100, MelanA and Tyrosinase, allow differential diagnosis (10). Therefore, the integration of clinical and histological assessment is essential for the diagnosis of SCM (2,8). Diagnosis of SCM is often delayed until patients exhibit advanced-stage disease, typically with widespread metastasis and poor treatment outcomes (3,6,12,13).

A limited number of case reports and incomplete retrospective case studies of the differential diagnostic viewpoints of SCM exist (3,4,11–15). To the best of our knowledge, few studies have reported SCM incidence, clinicopathologic features, treatment, treatment outcome and disease-specific independent prognostic factors. Thus, the present study performed a retrospective analysis of a series of clinical cases using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program.

Materials and methods

Data collection

In the present study, data was analyzed from the SEER Program, National Cancer Institute Public Use Dataset, which contains publically available records of 18 population-based cancer registries, which together represent 28% of the USA population. Data were extracted regarding patients with a primary diagnosis of SCM, according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3), using histology codes: 8772/3 (16). Cases were excluded if treatment or outcome data were unavailable for survival analysis. The data extraction was carried out with the official software SEER*Stat, version 8.3.4. (URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/data/).

Statistical analyses

Overall Statistical analysis was accomplished using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; version 23.0, for Windows; IBM Corp., Armonk, IL, USA). χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used to analyze associations among baseline parameters. The primary endpoint in the present study was considered to be the date of SCM-associated mortality. The time point between the date of diagnosis and the date of SCM-associated mortality was defined as disease-specific survival (DSS). Mortalities associated with SCM were considered to be events, while deaths attributed to other causes were considered to be ‘censored observations’. In terms of overall survival (OS) and DSS rates, Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test were utilized and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to identify significant risk factors for survival outcomes. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Study population and characteristics

The following demographic and clinicopathological characteristics were selected for analysis: Age at diagnosis, ethnicity, primary tumor location, Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) stage, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, pathological grade (the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control staging system), SEER historic stage, treatment modalities, vital status and follow-up time (17). Unfortunately, complete data was not available for all cases.

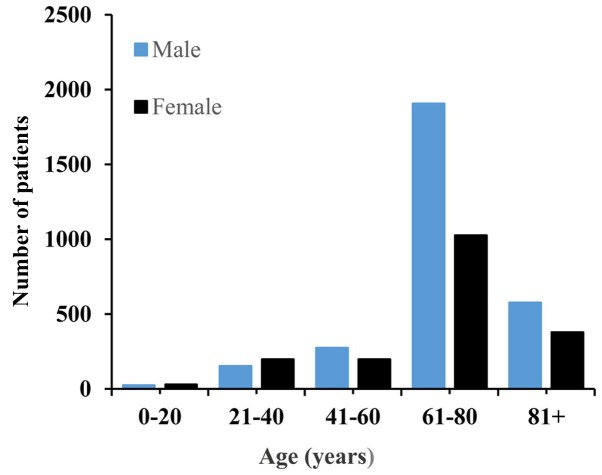

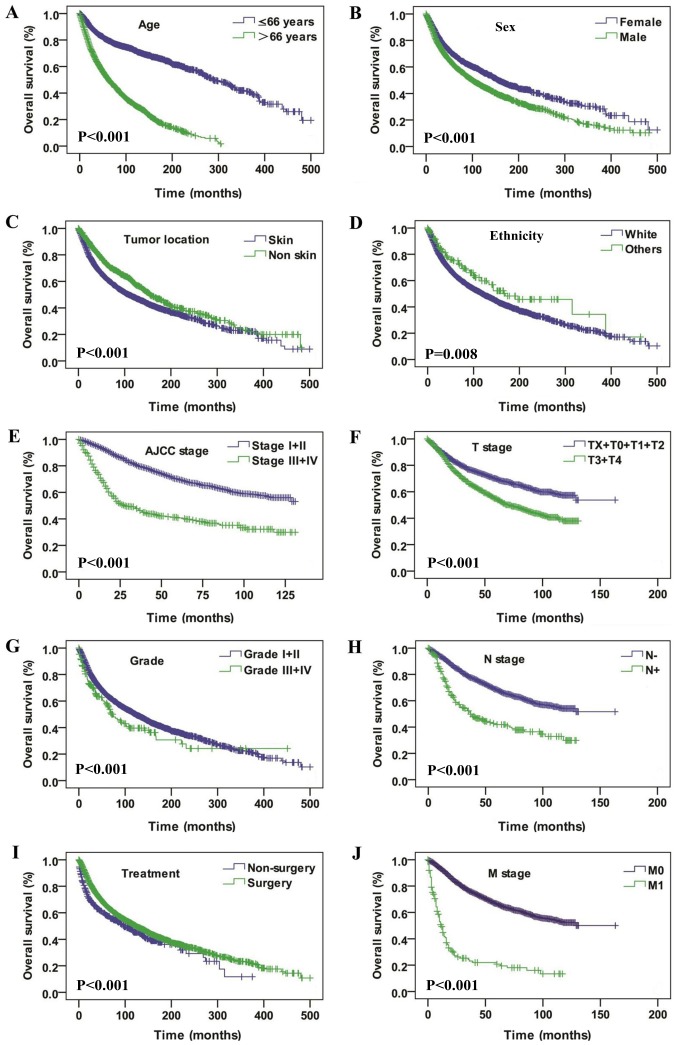

Data from 4,761 patient diagnosed with SCM between 1973 and 2017 was retrieved from the SEER database. The total cohort consisted of 1,829 women and 2,932 men, with a female:male ratio of 0.62:1. The patients' age ranged from 3–101 years and a median age of 66 years. The age and sex distributions are presented in Fig. 1. The median follow-up time was 53 months (range, 0–500 months). Regarding ethnicity, Caucasian people accounted for 96.7% of the study population. The majority of the cases of SCM had originated from the skin, and the eye and bony orbits were the second-most affected tumor site. Surgical resection was performed in 88.7% cases. The basic demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of the whole patients are summarized in Table I. Kaplan-Meier analysis was utilized for time-to-event analysis. Statistically significant differences in OS rate were identified depending on age (P<0.001), sex (P<0.001), tumor location (P<0.001), ethnicity (P=0.008), AJCC stage (P<0.001), T stage (P<0.001), pathological grade (P<0.001), N stage (P<0.001), treatment modalities (P<0.001) and M stage (P<0.001) (Fig. 2). Univariate Cox regression analysis analysis revealed that age, ethnicity, sex, tumor location, pathological grade, AJCC stage, T stage, N stage, M stage, SEER historic stage and treatment modalities were associated with OS (Table II). Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that positive N stage, age >66 years and SEER historic stage of regional and distant metastasis were factors independently associated with worse OS (Table III).

Figure 1.

The age and sex distribution of spindle cell melanoma cases.

Table I.

The baseline characteristics of the SCM cases extracted from the SEER database.

| DSS | OS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Alive | Dead | P-value | Alive | Dead | P-value |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤66 years | 1,333 | 361 | <0.001 | 1,512 | 621 | <0.001 |

| >66 years | 710 | 406 | 1,095 | 1,533 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 878 | 274 | <0.001 | 1,066 | 763 | <0.001 |

| Male | 1,165 | 493 | 1,541 | 1,391 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 1,947 | 745 | 0.009 | 2,506 | 2,098 | 0.008 |

| Black | 16 | 9 | 17 | 17 | ||

| Others | 80 | 13 | 84 | 39 | ||

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Eyes and bony orbits | 383 | 118 | <0.001 | 433 | 294 | <0.001 |

| Internal organs | 7 | 14 | 9 | 21 | ||

| Nose and mouth | 18 | 20 | 19 | 29 | ||

| Skin | 1,624 | 587 | 2,131 | 1,766 | ||

| Other site | 11 | 28 | 15 | 44 | ||

| Grade | ||||||

| I | 26 | 4 | <0.001 | 30 | 8 | <0.001 |

| II | 16 | 1 | 20 | 8 | ||

| III | 16 | 20 | 20 | 40 | ||

| IV | 12 | 16 | 15 | 31 | ||

| Unknown | 1,973 | 726 | 2,522 | 2,067 | ||

| AJCC stage | ||||||

| I | 552 | 42 | <0.001 | 745 | 184 | <0.001 |

| II | 533 | 118 | 729 | 371 | ||

| III | 138 | 57 | 176 | 115 | ||

| IV | 36 | 73 | 50 | 115 | ||

| T stage | ||||||

| T0 | 22 | 26 | <0.001 | 30 | 40 | <0.001 |

| T1 | 394 | 38 | 524 | 148 | ||

| T2 | 345 | 44 | 451 | 154 | ||

| T3 | 244 | 60 | 347 | 178 | ||

| T4 | 278 | 117 | 375 | 284 | ||

| TX | 99 | 42 | 144 | 125 | ||

| N stage | ||||||

| N0 | 1,226 | 210 | <0.001 | 1,656 | 683 | <0.001 |

| N1 | 57 | 46 | 77 | 79 | ||

| N2 | 35 | 16 | 46 | 38 | ||

| NX | 65 | 55 | 93 | 129 | ||

| M stage | ||||||

| M0 | 1,324 | 246 | <0.001 | 1,796 | 779 | <0.001 |

| M1 | 34 | 73 | 48 | 114 | ||

| MX | 25 | 8 | 28 | 36 | ||

| SEER stage | ||||||

| Localized | 1,499 | 305 | <0.001 | 1,893 | 1,133 | <0.001 |

| Regional | 419 | 263 | 547 | 632 | ||

| Distant | 8 | 9 | 14 | 18 | ||

| Unknown | 70 | 53 | 88 | 143 | ||

| Treatment | ||||||

| Non-surgery | 208 | 109 | 0.011 | 266 | 255 | 0.195 |

| Surgery | 1,827 | 655 | 2,332 | 1,891 | ||

| Unknown | 8 | 3 | 9 | 8 | ||

SCM, spindle cell melanoma; OS, overall survival; DSS, disease specific survival; T, tumor; N, node; M, metastasis; SEER, the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results; AJCC stage, American joint committee on cancer stage. TX, T stage unknown; NX, N stage unknown; MX, M stage unknown.

Figure 2.

Overall survival curves of patients with spindle cell melanoma compared according to (A) age, (B) sex, (C) tumor location, (D) ethnicity, (E) AJCC stage, (F) T stage, (G) pathological grade, (H) N stage, (I) treatment, and (J) M stage. The log-rank test was utilized to compare the curves. AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; T, tumor; N, node; M, metastasis.

Table II.

Univariate Cox regression analysis in terms of DSS and OS rates of SCM

| DSS | OS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age | ||||

| ≤66 years | 1.0 (reference) | <0.001 | 1.0 (reference) | <0.001 |

| >66 years | 2.372 (2.054–2.739) | 3.594 (3.257–3.965) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Black | 1.430 (0.741–2.760) | 0.286 | 1.345 (0.835–2.169) | 0.223 |

| Others | 0.497 (0.287–0.861) | 0.013 | 0.602 (0.439–0.827) | 0.002 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1.0 (reference) | <0.001 | 1.0 (reference) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.403 (1.210–1.627) | 1.355 (1.240–1.481) | ||

| Tumor location | ||||

| Eye and bony orbits | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Internal organs | 5.461 (3.132–9.522) | <0.001 | 3.817 (2.449–5.948) | <0.001 |

| Nose and mouth | 3.824 (2.377–6.151) | <0.001 | 3.231 (2.204–4.738) | <0.001 |

| Skin | 1.413 (1.159–1.722) | 0.001 | 1.642 (1.450–1.860) | <0.001 |

| Other site | 5.735 (3.790–8.679) | <0.001 | 3.877 (2.821–5.329) | <0.001 |

| Grade | ||||

| I | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| II | 0.247 (0.028–2.209) | 0.211 | 0.864 (0.324–2.304) | 0.771 |

| III | 4.496 (1.536–13.154) | 0.006 | 3.405 (1.593–7.278) | 0.002 |

| IV | 5.303 (1.773–15.867) | 0.003 | 3.923 (1.802–8.537) | 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.508 (0.564–4.209) | 0.413 | 1.781 (0.889–3.566) | 0.104 |

| AJCC stage | ||||

| I | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| II | 2.892 (2.033–4.113) | <0.001 | 2.072 (1.736–2.474) | <0.001 |

| III | 5.966 (4.002–8.895) | <0.001 | 2.896 (2.293–3.658) | <0.001 |

| IV | 25.917 (17.641–38.075) | <0.001 | 10.091 (7.968–12.781) | <0.001 |

| T stage | ||||

| T0 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| T1 | 0.087 (0.053–0.143) | <0.001 | 0.214 (0.151–0.304) | <0.001 |

| T2 | 0.113 (0.069–0.183) | <0.001 | 0.267 (0.189–0.378) | <0.001 |

| T3 | 0.217 (0.137–0.344) | <0.001 | 0.392 (0.278–0.552) | <0.001 |

| T4 | 0.391 (0.256–0.599) | <0.001 | 0.609 (0.437–0.848) | 0.003 |

| TX | 0.378 (0.232–0.617) | <0.001 | 0.627 (0.439–0.895) | 0.010 |

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| N1 | 4.273 (3.103–5.883) | <0.001 | 2.320 (1.837–2.929) | <0.001 |

| N2 | 3.448 (2.072–5.737) | <0.001 | 2.296 (1.656–3.185) | <0.001 |

| NX | 4.812 (3.572–6.483) | <0.001 | 3.306 (2.737–3.994) | <0.001 |

| M stage | ||||

| M0 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| M1 | 10.339 (7.923–13.491) | <0.001 | 5.559 (4.556–6.783) | <0.001 |

| MX | 1.337 (0.661–2.705) | 0.419 | 1.783 (1.276–2.491) | 0.001 |

| SEER stage | ||||

| Localized | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Regional | 2.914 (2.469–3.439) | <0.001 | 1.921 (1.742–2.119) | <0.001 |

| Distant | 20.058(10.243–39.278) | <0.001 | 8.328 (5.204–13.328) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 2.828 (2.112–3.786) | <0.001 | 1.791 (1.505–2.132) | <0.001 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Non-surgery | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Surgery | 0.671 (0.548–0.822) | <0.001 | 0.761 (0.667–0.867) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 0.649 (0.206–2.044) | 0.460 | 0.679 (0.336–1.374) | 0.282 |

SCM, spindle cell melanoma; OS, overall survival; DSS, disease specific survival; SEER, the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results; AJCC, American joint committee on cancer; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; TX, T stage unknown; NX, N stage unknown; MX, M stage unknown. Reference was used as the parameter against which HR was calculated.

Table III.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of SCM for DSS and OS rates.

| DSS | OS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age | ||||

| ≤66 years | 1.0 (reference) | <0.001 | 1.0 (reference) | <0.001 |

| >66 years | 2.502 (1.900–3.296) | 3.799 (3.160–4.568) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Black | 2.286 (0.727–7.196) | 0.157 | 2.664 (1.187–5.980) | 0.018 |

| Others | 1.564 (0.690–3.544) | 0.284 | 1.297 (0.731–2.303) | 0.374 |

| T stage | ||||

| TX+T0+T1+T2 | 1.0 (reference) | <0.001 | 1.0 (reference) | <0.001 |

| T3+T4 | 2.113 (1.567–2.847) | 1.485 (1.261–1.749) | ||

| N stage | ||||

| Negative | 1.0 (reference) | <0.001 | 1.0 (reference) | 0.001 |

| Positive | 2.437 (1.617–3.673) | 1.564 (1.204–2.031) | ||

| SEER stage | ||||

| Localized | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | ||

| Regional | 1.682 (1.199–2.361) | 0.003 | 1.458 (1.208–1.760) | <0.001 |

| Distant | 57.206 (22.241–147.138) | <0.001 | 18.856 (10.145–35.047) | <0.001 |

SCM, spindle cell melanoma; OS overall survival; DSS, disease specific survival; SEER, the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results; AJCC, American joint Committee on Cancer; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; TX, T stage unknown. Reference was used as the parameter against which HR was calculated.

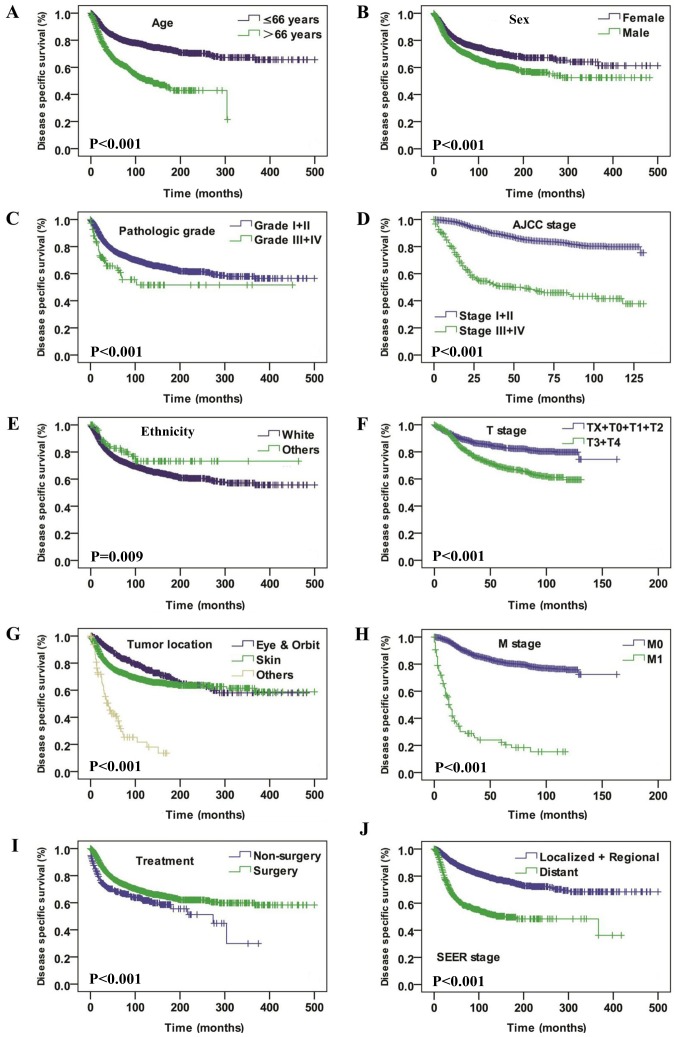

Significant differences in the DSS analysis were also identified depending on age (P<0.001), sex (P<0.001), pathological grade (P<0.001), AJCC stage (P<0.001), ethnicity (P=0.009), T stage (P<0.001), tumor location (P<0.001), M stage (P<0.001), treatment modalities (P<0.001), and SEER historic stage (P<0.001) (Fig. 3). Univariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that age, ethnicity, sex, tumor location, pathological grade, AJCC stage, T stage, N stage, M stage, SEER historic stage and treatment modalities were associated with DSS (Table II). The multivariate Cox regression model revealed that age >66 years T3+T4 stage, positive N-stage and SEER historic stage of regional and distant metastasis were independently associated with a poor OS rate (Table III).

Figure 3.

Disease specific survival curves of patients with spindle cell melanoma compared according to (A) age, (B) sex, (C) pathological grade, (D) AJCC stage, (E) ethnicity and (F) T stage, (G) tumor location, (H) M stage, (I) treatment and (J) SEER stage. The log-rank test was utilized to compare curves. AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; T, tumor; N, node; M, metastasis; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results.

Discussion

As a morphological variant of melanoma, SCM is rare and its incidence has been variably reported between 3 and 14% of all melanoma cases (including desmoplastic melanoma) (15,18,19). Diagnosis of SCM is challenging and awareness of its clinical and cytological features as well as immunohistochemical markers are essential to reach the correct diagnosis (9,10,15). Due to the rarity of SCM, its clinical and prognostic characteristics remain to be fully elucidated. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate SCM incidence as well as survival analysis on a large scale.

The present study demonstrates that the incidence of SCM was highest in the 6–8th decade of life in males. Caucasian people accounted for the majority of the study population. SCM lesions originated most commonly from the skin and eyes, and the bony orbits were the second-most affected tumor site. SCM shares various features with conventional melanoma. Previous studies have demonstrated that melanomas arise from the melanocytes of the skin and eyes in response to intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli, including pro-inflammatory signals, oncogenes and UV radiation (12,20,21). Human pigmentation is a polygenic quantitative trait with high heritability and it is modulated by estrogen and androgens via regulation of melanin synthesis (22). This may explain why SCM mainly originates from skin and eyes and has a predilection of male and Caucasian people.

According to previous studies, it appears that age, sex, ethnicity and tumor location are important prognostic factors for patients with melanoma (22–24). The present study indicates that patients with SCM who were male, aged >66 years, Caucasian, or with tumors located in the skin were associated with poor OS and DSS rates. In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, age >66 years was independently associated with poor OS and DSS rates, which was in consistence with previous studies on melanoma (24–27). Seeing as it was demonstrated that SCM was more likely to occur in patients >66 years of age, potential poor tolerance of complications and common comorbidities of elderly patients should be also taken into consideration when making treatment protocol.

Pathological grade has been demonstrated to be an important prognostic factor for estimation of survival outcome in melanoma (17). The results of the present study indicate that well-differentiated SCM was associated with a relatively good outcome both in terms of OS and DSS rate, compared with poorly differentiated SCM. Advanced stage SCM was associated with a relatively poor OS and DSS rates compared with early-stage tumors. Cox multivariate regression also suggested that pathology was an important consideration, with advanced T stage, positive N stage and SEER historic stage of metastasis being independently associated with poor OS and DSS rates. This emphasizes that a full awareness of the morphological and clinical presentations of SCM are required for the accurate diagnosis of SCM. However, due to the unspecific clinical presentation of SCM, early detection is often delayed (4,12–14). Metastatic SCM from an unknown primary site should be taken into consideration when diagnosing SCM lesions (15,18,28). Fine-needle aspiration may be a rapid and effective tool for surveillance of recurrent and metastatic cases of SCM, however, accurate diagnosis is challenging owing to the varied cytologic morphologic appearances (6,29–31).

In the present study, surgery was the only identified treatment modality for SCM. The results indicate that surgery was favorable for OS and DSS rates. A previous study demonstrated that wide local excision with clear margins, sentinel node biopsy and regular follow-up examinations were crucial in the management of SCM (4). However, SCM cases should be monitored carefully as metastasis is possible fir multiple years after surgery (32). For tumors in complex anatomic regions, including the head and neck, the treatment of elderly patients or those at an advanced stage by radical surgery with clear margins is difficult (3). Under these circumstances, therapeutic planning is challenging (33). Therefore, multi-cancer randomized clinical trials are urgently required to improve the available treatment for this melanoma subtype.

While the SEER Program is a comprehensive and geographically representative registry, a few limitations of the present study should be noted. Due to alterations of the criteria for the histological diagnosis of SCM the diagnosis of SCM patients in the past may be inconsistent with more recent diagnoses. Another limitation is that complete data was not available for all cases. A number of important prognostic data, including surgical types, margin status and adjuvant therapies were either absent or incomplete in the available SEER data, and therefore there influence on prognosis could not be assessed. In addition, the results suggest that SCM patients may represent an older population, and data on comorbidities that may affect treatment protocols and outcomes is lacking. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large population study of SCM with a robust long-term follow-up survival assessment provided by SEER, which will improve the existing knowledge of the demographic of SCM, its clinicopathological features and disease-specific prognostic factors.

Overall, a large scale report of SCM demographic trends, clinicopathological features, treatment outcomes and disease-specific independent prognostic factors was presented. The results demonstrate that SCM mostly occurred in Caucasians and males, and the highest incidence occurred in the 6–8th decades of life. Age, ethnicity, T stage, N stage and SEER historic stage were independent prognostic factors of DSS and OS rates.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- SCM

spindle cell melanoma

- OS

overall survival

- DSS

disease specific survival

- SEER

the surveillance, epidemiology and end results

- AJCC stage

American Joint Committee on Cancer stage

- HR

hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

Funding

The present study was supported by The Scientific Research Foundation of Shanghai Stomatological Hospital, Fudan University (grant no. SSDCZ-2016-01).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the present study are available in the official software SEER*Stat, v.8.3.4 repository, [https://seer.cancer.gov/data/], and analyzed in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; v.23.0, for Windows; IBM Corp., Armonk, IL, USA).

Authors' contributions

ZX and PS were major contributors in the writing of the manuscript. FY and LF collected and collated the patient data. HZ analyzed and the interpreted patient data. AW was responsible for planning and organizing the study and checking the data and manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Due to the retrospective nature of this study, it was granted an exemption in writing by the University of Fudan institutional review board (IRB).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Winnepenninckx V, De Vos R, Stas M, van den Oord JJ. New phenotypical and ultrastructural findings in spindle cell (desmoplastic/neurotropic) melanoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2003;11:319–325. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200312000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz A, Valera A, Carrera C, Hakim S, Aguilera P, García A, Palou J, Puig S, Malvehy J, Alos L. Pigmented spindle cell nevus: Clues for differentiating it from spindle cell malignant melanoma. A comprehensive survey including clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and FISH studies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1733–1742. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318229cf66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dainichi T, Kobayashi C, Fujita S, Shiramizu K, Ishiko T, Kiryu H, Urabe K, Tsuneyoshi M, Furue M. Interdigital amelanotic spindle-cell melanoma mimicking an inflammatory process due to dermatophytosis. J Dermatol. 2007;34:716–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheff JS, Pane TA. Spindle cell melanoma arising from decades-old burn scar. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:274e–275e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b98e1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson CR, Minca EC, Kapil JP, Smith SC, Billings SD. Superficial malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor with overlying intradermal melanocytic nevus mimicking spindle cell melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1220–1225. doi: 10.1111/cup.12834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walia R, Jain D, Mathur SR, Iyer VK. Spindle cell melanoma: A comparison of the cytomorphological features with the epithelioid variant. Acta Cytol. 2013;57:557–561. doi: 10.1159/000354405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falconieri G, Bacchi CE, Luzar B. Cutaneous clear cell sarcoma: Report of three cases of a potentially underestimated mimicker of spindle cell melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:619–625. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182473190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeh I, Vemula SS, Mirza SA, McCalmont TH. Neurofibroma-like spindle cell melanoma: CD34 fingerprint and CGH for diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:668–670. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318244819a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tacha D, Qi W, Ra S, Bremer R, Yu C, Chu J, Hoang L, Robbins B. A newly developed mouse monoclonal SOX10 antibody is a highly sensitive and specific marker for malignant melanoma, including spindle cell and desmoplastic melanomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:530–536. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0077-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, Klaus BM, Möller P, Horst BA, Lennerz JK. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524–534. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stowman AM, Mills SE, Wick MR. Spindle cell melanoma and interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma: Do they represent the same process? Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:1270–1279. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rawandale NA, Suryawanshi KH. Primary spindle cell malignant melanoma of esophagus: An unusual finding. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:OD03–OD04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16121.7188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundersingh S, Majhi U, Narayanaswamy K, Balasubramanian S. Primary spindle cell melanoma of the urinary bladder. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:422–424. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.81612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agostini P, Rivero A, Parra Martin JA, Soares-de-Almeida L. Pedunculated polypoid melanoma. A case report of a rare spindle-cell variant of melanoma. Dermatol Online J J. 2015;21:pii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piao Y, Guo M, Gong Y. Diagnostic challenges of metastatic spindle cell melanoma on fine-needle aspiration specimens. Cancer. 2008;114:94–101. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A. International classification of diseases for oncology: ICD-O-3. World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elder DE. Pathological staging of melanoma. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1102:325–351. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-727-3_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murali R, Doubrovsky A, Watson GF, McKenzie PR, Lee CS, McLeod DJ, Uren RF, Stretch JR, Saw RP, Thompson JF, Scolyer RA. Diagnosis of metastatic melanoma by fine-needle biopsy: Analysis of 2,204 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127:385–397. doi: 10.1309/3QR4FC5PPWXA7N29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta SK, Rajwanshi AK, Das DK. Fine needle aspiration cytology smear patterns of malignant melanoma. Acta Cytol. 1985;29:983–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soengas MS, Patton EE. Location, Location, Location: Spatio-temporal cues that define the cell of origin in melanoma. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:559–561. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Lazar AJ, Davies MA, Homsi J, Papadopoulos NE, Hwu WJ, Bedikian AY, Woodman SE, Patel SP, Hwu P, Kim KB. BRAF, NRAS and KIT sequencing analysis of spindle cell melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:821–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2012.01950.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernando B, Ibarrola-Villava M, Fernandez LP, Peña-Chilet M, Llorca-Cardeñosa M, Oltra SS, Alonso S, Boyano MD, Martinez-Cadenas C, Ribas G. Sex-specific genetic effects associated with pigmentation, sensitivity to sunlight, and melanoma in a population of Spanish origin. Biol Sex Differ. 2016;7:17. doi: 10.1186/s13293-016-0070-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voinea S, Blidaru A, Panaitescu E, Sandru A. Impact of gender and primary tumor location on outcome of patients with cutaneous melanoma. J Med Life. 2016;9:444–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadakia S, Chan D, Mourad M, Ducic Y. The prognostic value of age, sex, and subsite in cutaneous head and neck melanoma: A clinical review of recent literature. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2016;9:e5079. doi: 10.17795/ijcp-5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, Thompson JF, Coit DG, Atkins MB, Ding S, Cochran AJ, Eggermont AM, Flaherty KT, et al. Age as a prognostic factor in patients with localized melanoma and regional metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3961–3968. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3100-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stokes WA, Lentsch EJ. Age is an independent poor prognostic factor in cutaneous head and neck melanoma. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:462–465. doi: 10.1002/lary.24315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arce PM, Camilon PR, Stokes WA, Nguyen SA, Lentsch EJ. Is sex an independent prognostic factor in cutaneous head and neck melanoma? Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1363–1367. doi: 10.1002/lary.24439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi G, Cobb C. A case of amelanotic spindle-cell melanoma presenting as metastases to breast and axillary lymph node: Diagnosis by FNA cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;22:246–249. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(200004)22:4<246::AID-DC10>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindsey KG, Ingram C, Bergeron J, Yang J. Cytological diagnosis of metastatic malignant melanoma by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2016;33:198–203. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayayo Artal E, Gomez-Aracil V, Mayayo Alvira R, Azua-Romeo J, Arraiza A. Spindle cell malignant melanoma metastatic to the breast from a pigmented lesion on the back. A case report. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:387–390. doi: 10.1159/000326390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arora SK, Gupta N, Kang M, Rajwanshi A. Fine-needle aspiration cytology in a case of metastatic spindle cell melanoma in liver. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:425–426. doi: 10.1002/dc.21197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santeusanio G, Ventura L, Mauriello A, Carosi M, Spagnoli LG, Maturo P, Terranova L, Romanini C. Isolated ovarian metastasis from a spindle cell malignant melanoma of the choroid 14 years after enucleation: Prognostic implication of the keratin immunophenotype. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2000;8:329–333. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200012000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gladfelter P, Darwish NHE, Mousa SA. Current status and future direction in the management of malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2017;27:403–410. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the present study are available in the official software SEER*Stat, v.8.3.4 repository, [https://seer.cancer.gov/data/], and analyzed in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; v.23.0, for Windows; IBM Corp., Armonk, IL, USA).