Abstract

The present study assessed the expression of solute carrier 6 member 1 (SLC6A1) in ovarian cancer (OC) tissues and evaluated the effect of silencing SLC6A1 or caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2) on the proliferation, migration, and invasion of SK-OV-3 OC cells. The levels of caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2) and SLC6A1 mRNA were also examined in OC SK-OV-3, OVCAR3 and A2780 cell lines. The mRNA levels of CDX2 and SLC6A1 in SK-OV-3 OC cells were assessed following transection with microRNA (miR) 133a mimics; the mRNA and protein levels of SLC6A1 were determined following the silencing of CDX2, and the mRNA expression of CDX2 was gauged following the silencing of SLC6A1. A luciferase reporter assay was performed to assess the effect of miR133a on the CDX2 and SLC6A1 3′-untranslated regions (3′UTRs). The proliferation, migration and invasion rate of SK-OV-3 cells were then examined following the silencing of CDX2 or SLC6A1. The expression of SLC6A1 was increased in OC compared with adjacent tissue. The expression of CDX2 and SLC6A1 in SK-OV-3 and OVCAR3 cells was increased compared with A2780 cells (P<0.05). The level of CDX2 and SLC6A1 mRNA in SK-OV-3 cells decreased when the cells were transected with the miR133a mimics, compared with a negative control (P<0.05). Transfection with the miR133a mimics significantly reduced the luciferase activity of reporter plasmids with the SLC6A1 or CDX2 3′UTRs (P<0.05). The mRNA level of CDX2 was decreased subsequent to the silencing of SLC6A1; the mRNA and protein level of SLC6A1 were decreased when CDX2 was silenced (P<0.05). The proliferation, migration, and invasion of SK-OV-3 cells were significantly reduced following the silencing of CDX2 or SLC6A1 (P<0.05). CDX2 may therefore be inferred to promote the proliferation, migration and invasion in SK-OV-3 OC cells, acting as a competing endogenous RNA.

Keywords: caudal type homeobox 2, solute carrier 6 member 1, microRNA-133a

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) has the highest mortality rate of any gynecological cancer worldwide (1–7). During the early stages of the disease, OC tends to metastasize to the abdominal cavity and pelvis (6,8–10). As a result, approximately three-quarters of OC patients have already developed metastases at the time of first diagnosis. Despite numerous advances in surgery and chemotherapy, the overall survival rate of OC patients remains unsatisfactory, with a 5-year survival rate of ~30% (11). As the poor prognosis of this disease is associated with the occurrence of cancer metastasis and recurrence, the examination of the mechanisms involved in OC metastasis is important.

Solute carrier family 6 member 1 (SLC6A1) is a crucial component of the GABAergic system, the abnormal expression of which may be responsible for GABAergic malfunction in various pathological conditions (12). Levels of SLC6A1 in the mucosa of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia have been observed to be upregulated >10-fold compared with normal gastric mucosa tissues (13). SLC6A1 is thus a potential marker for the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer and precancerous lesions. In clear cell renal cell carcinoma, SLC6A1 has a high expression and miR-200c-3p has a low expression. Lower SLC6A1 expression demonstrated longer survival time and higher survival rate. SLC6A1 is a direct target of miR-200c. The ability of cellular migration and invasion of a number of cancer types, including renal cell carcinoma, are regulated by miR-200c (14). miR-200c is decreased expression in numerous types of cancer. In non-small cell lung cancer, the downregulation of miR-200c promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression (15). In gastric cancer, miR-200c prohibits TGF-β-induced-EMT to restore trastuzumab sensitivity by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2 (16). Therefore, SLC6A1 may promote the migration and invasion of renal cell carcinoma. However, the expression and function of SLC6A1 in OC remain unknown.

The present study identified that CDX2 mRNA may act as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) that regulates the expression of SLC6A1 through competition for microRNA (miRNA/miR) 133a in SK-OV-3 OC cells, potentially providing a novel insight into the pathogenesis of OC.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

The tissue array (bc110118) was purchased from US Biomax (Rockville, MD, USA). This array included 45 cases of epithelial ovarian cancer and 9 cases of normal ovarian tissue. Tissue samples were fixed in 4% formalin at 4°C and embedded in paraffin.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tissue samples were sectioned to 4-µm thick, deparaffinized in xylene, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, subjected to antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for 30 min in a pressure cooker, and washed in PBS. PBS was used for all subsequent washes and for antiserum dilution. The endogenous peroxidase activity of the tissue sections was quenched using 3% hydrogen peroxide and blocked with PBS containing 10% goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 1 h at 37°C. Next, slides were incubated with a rabbit monoclonal SLC6A1 antibody (dilution, 1:200; cat. no., ab180516; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4°C. Negative controls included omission of primary antibody and the use of irrelevant primary antibody (dilution using PBS, 1:100; p53; ab131442; Abcam). Following three washes of 3 min to remove excess antibody, the slides were incubated with anti-rabbit biotinylated antibodies (dilution, 1:300; bs-0312R; Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) for 1 h at 37°C. All slides were washed in PBS and were incubated in avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (dilution, 1:300; Origene Technologies, Inc., Beijing, China) for 30 min in humidified chambers at 37°C. Diaminobenzidine (Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used as a chromogen, and 1% hematoxylin (C0105, Beyotime Biotechnology) for 5 min at 4°C was used as a nuclear counter-stain.

Slides were independently evaluated by 3 pathologists for the distribution and intensity of signal, as described previously (17). Intensity was scored between 0 and 3, as follows: 0, negative; 1, low immunopositivity; 2, moderate immunopositivity; 3, intense immunopositivity. A mean of 22 fields of view were observed for each sample.

Cell lines and culture conditions

SK-OV-3, OVCAR3 and A2780 OC cell lines were purchased from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 or DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in humidified air at 37°C with 5% CO2. miRNA mimics were purchased from Shanghai Genepharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Non-specific short interfering RNA was used as a negative control. miR-133a mimics sequence: 5′-AGCUGGUAAAAUGGAACCAAAU-3′; NC: 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ miR-133a inhibitors: 5′-CAGCUGGUUGAAGGGGACCAAA-3′; inhibitors NC: 5′-GAGUACUUUUGUGUAGUACAA-3′. CDX2 siRNA sequence: 5′-GGGUUGUUGGUCUGUGUAACA-3′; SLC6A1 siRNA sequence: GGAUCUGUCCGACAGUCAAGA. The transfection reagent siRNA-mate was provided from Genepharma Co., Ltd. (G04002; Shanghai, China). The transfection protocol was described by the previous studies (18).

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) assay

The proliferation of cells was detected by an EdU assay, as described previously (19).

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using an RNA Pure High-purity Total RNA Rapid Extraction kit (BioTeke Corporation, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was synthesized using the iSCRIPT cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). SLC6A1 or CDX2 mRNA expression levels were examined by qPCR using the iQ5 Real-Time PCR Detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and All-in-One qPCR mix with SYBR-Green (GeneCopoeia, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). β-actin values were used for normalization. Primers used for PCR were purchased from GeneCopoeia, Inc. [cat. nos., HQP017395 (SLC6A1), HQP016381 (β-actin) and HQP000553 (CDX2); Rockville, MD, USA]. Amplification was performed with an initial 10-min denaturation step at 95°C, followed by 40 amplification cycles of 10 sec at 95°C, 20 sec at 60°C and 10 sec at 72°C. For detecting miR133a, reverse transcription was performed following the applied GeneCopoeia protocol and normalization was performed against U6. Primers were purchased from GeneCopoeia (HmiRQP3057 and HmiRQP9001). The 2−ΔΔCq method was employed for quantification (20).

Western blot analysis

Expression of SLC6A1 and CDX2 protein was analyzed by western blotting, as previously described (21). The primary antibodies used included monoclonal rabbit anti-SLC6A1 (dilution, 1:5,000; DCABH-6396; Creative-Diagnostics, Shirley, USA), monoclonal rabbit anti-CDX2 (dilution, 1:5,000; ab76541, Abcam) and polyclonal rabbit anti-β-actin (dilution, 1:5,000; ab8226, Abcam). The bands were detected via enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China) and quantified using ImageQuant 3.3 software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Shanghai, China).

Dual luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter assay was performed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (22–25). For the luciferase reporter assay, wild type or mutant reporter constructs (termed WT or Mut; purchased from Genepharma Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were co-transfected into SKOV3 cells in 24-well plates with 100 nM miR-133a mimics or 100 nM miR-NC and Renilla plasmid using Endofectin™-Plus (GeneCopoeia). Reporter gene assay was performed 48 h post-transfection using the Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega Corporation). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized for transfection efficiency using the corresponding Renilla luciferase activity.

Transwell invasion assay

Invasion assays were performed as follows: The upper side was coated using basement membrane matrix for 2 h at 37°C. The MCF-7 cells were added into the top chamber, and then incubated for 48 h. Paraformaldehyde (6%) was used to fix the invasive cells. Then, stained in 0.5% crystal violet (Beyotime) and counted (26–28).

Wound healing assay

The cell migration assays were performed in accordance with our previous studies. Briefly, ovarian cancer cells were cultured in a 6-well plates at ~80% confluence. The medium was replaced with serum-free medium. After the wounding, the distance between two wounds was measured at 0 and 72 h (29–32).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All values were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-test or analysis of variance followed by a Scheffe test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

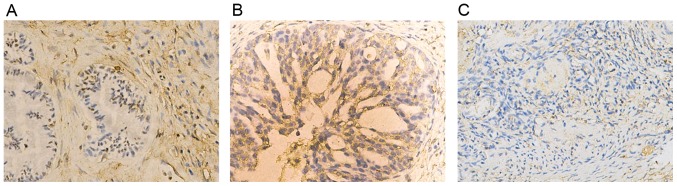

Expression of SLC6A1 in OC tissues

The expression profile of SLC6A1 in OC was not previously fully elucidated. In the present study, the expression pattern of SLC6A1 in normal ovary and OC tissue samples was examined using IHC. The expression of SLC6A1 was markedly higher in OC tissues compared with adjacent tissue (Fig. 1). SLC6A1 expression was localized at the plasma membrane and in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Expression of SLC6A1 in ovarian cancer tissues, as determined with immunohistochemistry. Expression in (A) ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma (B) serious adenocarcinoma and (C) normal ovarian tissues. Magnification, ×200. SLC6A1, solute carrier family 6 member 1.

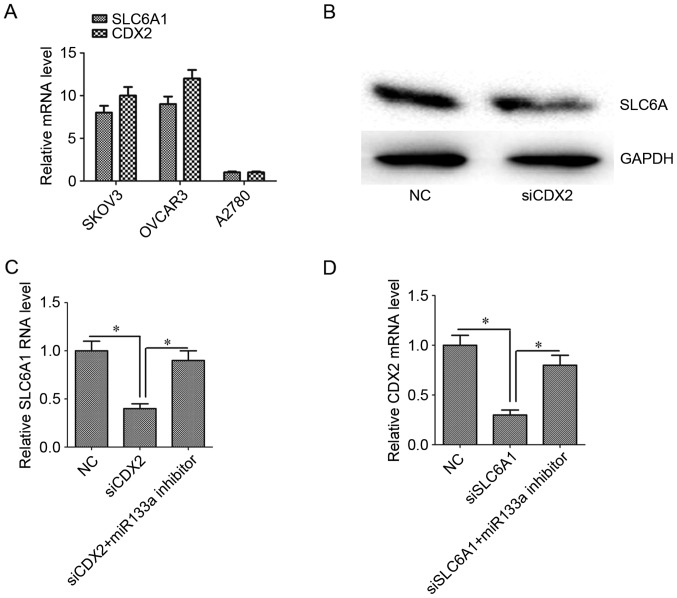

Expression of SLC6A1 and CDX2 in OC cells

The expression of SLC6A1 and CDX2 mRNA was assessed in SK-OV-3, OVCAR3 and A2780 cells. The expression of SLC6A1 and CDX2 mRNA in SK-OV-3 and OVCAR3 cells was higher than that in A2780 cells (Fig. 2A; P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Relative expression of SLC6A1 and CDX2 mRNA and protein. (A) SLC6A1 and CDX2 mRNA was detected in A2780, OVCAR3 and SK-OV-3 ovarian carcinoma cells. SK-OV-3 cells were used for further experiments. Silencing CDX2 downregulated the expression of SLC6A1 (B) protein and (C) mRNA. (D) Silencing SLC6A1 downregulated the expression of SLC6A1 mRNA. Inhibiting miR133a reversed the effect. Results are mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05. SLC6A1, solute carrier family 6 member 1; CDX2, caudal-type homeobox protein 2.

Interaction between SLC6A1 and CDX2 in SK-OV-3 OC cells

In the present study, transfection efficiency of OVCAR3 cells was low. Therefore, SK-OV-3 cells were chosen on account of their high expression of SLC6A1 and CDX2. The level of SLC6A1 protein and mRNA expression decreased when CDX2 expression was silenced (Fig. 2B and C; P<0.05). Similarly, the level of CDX2 mRNA was decreased when SLC6A1 expression was silenced (Fig. 2D; P<0.05). When miR133a expression was silenced, the association between SLC6A1 and CDX2 expression levels was reduced (Fig. 2C and D).

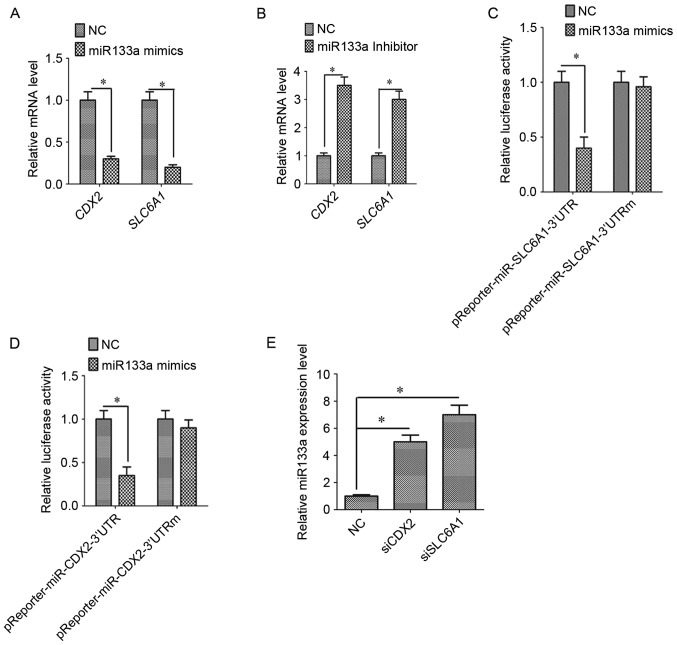

SLC6A1 and CDX2 are targets of miR133a

To determine whether SLC6A1 and CDX2 are targets of miR133a, miR133a mimics and inhibitors were transfected into SK-OV-3 OC cells. The expression of SLC6A1 and CDX2 was decreased when cells were transfected with miR133a mimics (Fig. 3A; P<0.05). By contrast, the expression of SLC6A1 and CDX2 was increased when transfected with miR133a inhibitors (Fig. 3B; P<0.05). Luciferase assays confirmed the existence of specific crosstalk between the SLC6A1 and CDX2 mRNAs through competition for miR133a binding (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Association between SLC6A1 and CDX2 in SK-OV-3 cells. (A) miR-133a mimics inhibited the mRNA expression of SLC6A1 and CDX2. (B) miR-133a inhibitors upregulated the mRNA expression of SLC6A1 and CDX2. miR-133a mimics reduced the relative luciferase activity of the (C) SLC6A1 and (D) CDX2 3′UTRs compared with mutant 3′UTRs. (E) Silencing CDX2 or SLC6A1 with specific siRNAs upregulated miR-133a expression. Results are mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05. SLC6A1, solute carrier family 6 member 1; CDX2, caudal-type homeobox protein 2; miR-133a, microRNA-133a; 3′UTR, 3′-untranslated region; NC, negative control oligo; siCDX2, short interfering RNA targeted at CDX2; siSLC6A1, short interfering RNA targeted at SLC6A1.

Silencing SLC6A1 and CDX2 increased the expression of miR133a

We hypothesize that SLC6A1 and CDX2 regulate miR133a. The expression of miR133a increased following the silencing of SLC6A1 or CDX2 expression (Fig. 3E; P<0.05). To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first evidence for a positive association between SLC6A1 and CDX2 expression and for crosstalk between miR133a, SLC6A1 and CDX2.

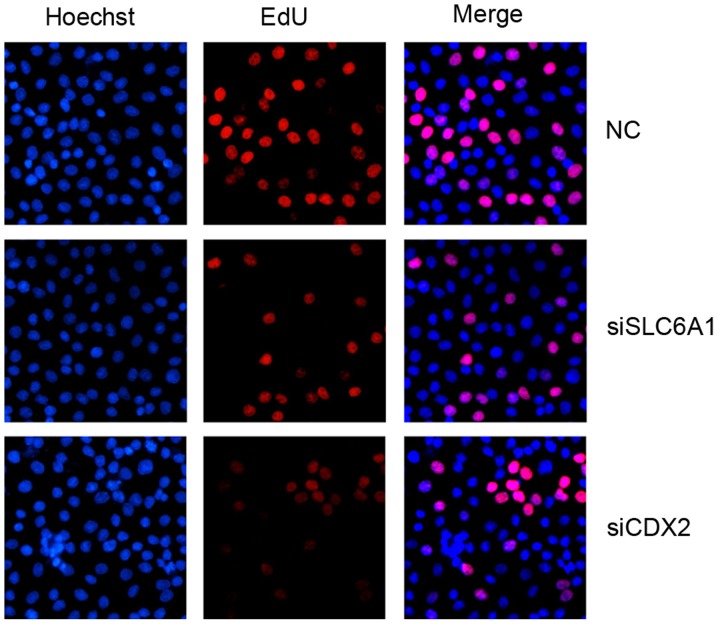

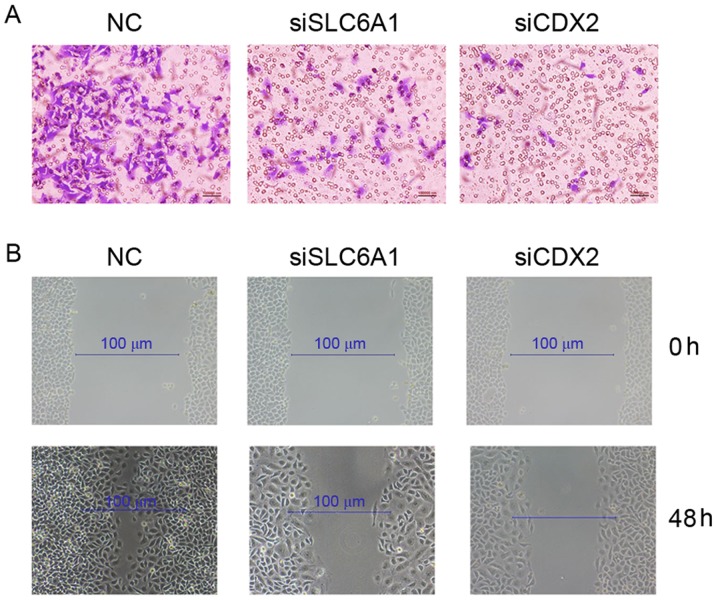

Silencing SLC6A1 and CDX2 inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion of SK-OV-3 cells

The proliferation (Fig. 4), migration and invasion (Fig. 5) of SK-OV-3 cells were markedly reduced following the silencing of SLC6A1 and CDX2 expression.

Figure 4.

Detection of cell proliferation in SK-OV-3 cells by an EdU assay. Magnification, ×200. EdU, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine; NC, negative control; siSLC6A1, short interfering RNA targeted at solute carrier family 6 member 1; siCDX2, short interfering RNA targeted at caudal-type homeobox protein 2.

Figure 5.

Detection of the rate of (A) invasion and (B) migration in SK-OV-3 cells. NC, negative control; siSLC6A1, short interfering RNA targeted at solute carrier family 6 member 1; siCDX2, short interfering RNA targeted at caudal-type homeobox protein 2.

Discussion

In the present study, SLC6A1 expression was increased in OC compared with adjacent tissue and SLC6A1 expression was revealed to be associated with CDX2 via miR133a. The proliferation, migration, and invasion of OC SK-OV-3 cells were regulated by SLC6A1, CDX2 and miR133a.

SLC6A1 is a crucial component of the GABAergic system. The abnormal expression of SLC6A1 may be responsible for GABAergic malfunction in various pathological conditions (12). SLC6A1 expression was >10-fold higher in the mucosa of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia tissues when compared with normal gastric mucosa tissue, and so SLC6A1 is a potential marker for the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer and precancerous lesions (13). However, the role served by SLC6A1 in OC is unknown. The current study demonstrated that the expression of SLC6A1 was increased in OC tissue compared to normal tissue, and SLC6A1-knockdown inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion of OC cells. These data indicate SLC6A1 may serve an important role in OC progression.

CDX2 is a nuclear homeobox transcription factor in the caudal-associated family of CDX homeobox genes (33). CDX2 functions in the control of normal embryonic development, cell proliferation, differentiation, adhesion and apoptosis (34–38). CDX2 is upregulated in numerous types of human gastrointestinal cancer and mutations in CDX2 in gastric epithelial cells are associated with tumorigenesis (39–42). Expression of CDX2 is upregulated by IL-6 through the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription pathway (43). In the present study, silencing CDX2 expression inhibited the proliferation, migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells, indicating that CDX2 may regulate ovarian cancer growth and metastasis.

ceRNAs are transcripts that regulate the expression of each other through competition for their shared miRNA recognition elements (44,45). High-mobility group AT-hook 2 is a protein that can promote lung cancer progression in mouse and human cells by functioning as a ceRNA for the let-7 miRNA family (46). Phosphatase and tensin homolog mRNA acts as a ceRNA, regulating zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 2 and BRAF expression to promote melanoma genesis (47). The BRAF pseudogene functions as a ceRNA to regulate lymphoma (48). ceRNA regulatory networks serve an important role in cancer progression (49,50). In the present study, the association between SLC6A1 and CDX2 expression was dependent on miR133a, indicating that SLC6A1 mRNA may function as a ceRNA that regulates CDX2 expression by competitively binding with miR133a. miR133a is abnormally expressed in numerous cancer types. Decreased expression of miR133a is closely associated with the progression of tumors (51,52). miR133a is involved in the initiation and malignant progression of human epithelial OC (53). The present study identified that SLC6A1 and CDX2 were direct targets of miR133a and also indicated that the aberrant expression of SLC6A1 may serve a role in OC.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that the association between SLC6A1 and CDX2 regulated OC SK-OV-3 cell proliferation, migration and invasion, through miR133a. The study provides a novel insight into ovarian cancer pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets. Further studies will be performed to consider the interaction between SLC6A1 and CDX2 in vivo.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Chengdu Danfeng Technology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China) for providing ideas and assistance.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

YZ and XZ made substantial contributions to the conception of the present study. YZ, undertook data interpretation of data for the work. YH and CL contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bast RC, Jr, Hennessy B, Mills GB. The biology of ovarian cancer: New opportunities for translation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masoumi-Moghaddam S, Amini A, Wei AQ, Robertson G, Morris DL. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression correlates with serum CA125 and represents a useful tool in prediction of refractoriness to platinum-based chemotherapy and ascites formation in epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:28491–28501. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagaraj AB, Joseph P, Kovalenko O, Singh S, Armstrong A, Redline R, Resnick K, Zanotti K, Waggoner S, DiFeo A. Critical role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in driving epithelial ovarian cancer platinum resistance. Oncotarget. 2015;6:23720–23734. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prislei S, Martinelli E, Zannoni GF, Petrillo M, Filippetti F, Mariani M, Mozzetti S, Raspaglio G, Scambia G, Ferlini C. Role and prognostic significance of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition factor ZEB2 in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:18966–18979. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu YH, Chang TH, Huang YF, Chen CC, Chou CY. COL11A1 confers chemoresistance on ovarian cancer cells through the activation of Akt/c/EBPβ pathway and PDK1 stabilization. Oncotarget. 2015;6:23748–23763. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng R, Zhang R, Song X, Ni L, Lai Z, Liu C, Ye W. The long non-coding RNA MALAT1 activates Nrf2 signaling to protect human umbilical vein endothelial cells from hydrogen peroxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;495:2532–2538. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.12.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho HY, Kim K, Jeon YT, Kim YB, No JH. CA19-9 elevation in ovarian mature cystic teratoma: Discrimination from ovarian cancer-CA19-9 level in teratoma. Med Sci Monit. 2013;19:230–235. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barger CJ, Zhang W, Hillman J, Stablewski AB, Higgins MJ, Vanderhyden BC, Odunsi K, Karpf AR. Genetic determinants of FOXM1 overexpression in epithelial ovarian cancer and functional contribution to cell cycle progression. Oncotarget. 2015;6:27613–27627. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu S, Fu GB, Tao Z, OuYang J, Kong F, Jiang BH, Wan X, Chen K. MiR-497 decreases cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells by targeting mTOR/P70S6K1. Oncotarget. 2015;6:26457–26471. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rustin G, van der Burg M, Griffin C, Qian W, Swart AM. Early versus delayed treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2011;377:380–381. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao M, Niu G, Sheng Z, Wang Z, Fei J. Identification of a Smad4/YY1-recognized and BMP2-responsive transcriptional regulatory module in the promoter of mouse GABA transporter subtype I (Gat1) gene. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4062–4071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2964-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KR, Oh SY, Park UC, Wang JH, Lee JD, Kweon HJ, Kim SY, Park SH, Choi DK, Kim CG, et al. Gene expression profiling using oligonucleotide microarray in atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2007;49:209–224. (In Korean) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maolakuerban N, Azhati B, Tusong H, Abula A, Yasheng A, Xireyazidan A. MiR-200c-3p inhibits cell migration and invasion of clear cell renal cell carcinoma via regulating SLC6A1. Cancer Biol Ther. 2018;19:282–291. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2017.1394551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lei W, Kang W, Nan Y, Lei Z, Zhongdong L, Demin L, Lei S, Hairong H. The downregulation of miR-200c promotes lactate dehydrogenase A expression and non-small cell lung cancer progression. Oncol Res. 2018 Jan 10; doi: 10.3727/096504018X15151486241153. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou X, Men X, Zhao R, Han J, Fan Z, Wang Y, Lv Y, Zuo J, Zhao L, Sang M, et al. miR-200c inhibits TGF-β-induced-EMT to restore trastuzumab sensitivity by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2 in gastric cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2018;25:68–76. doi: 10.1038/s41417-017-0005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Falco M, Fedele V, Cobellis L, Mastrogiacomo A, Giraldi D, Leone S, De Luca L, Laforgia V, De Luca A. Pattern of expression of cyclin D1/CDK4 complex in human placenta during gestation. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;317:187–194. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0880-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu X, Zhao W, Yang X, Wang Z, Hao M. miR-375 affects the proliferation, invasion, and apoptosis of HPV16-positive human cervical cancer cells by targeting IGF-1R. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:851–858. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Y, Arora A, Min W, Roifman CM, Grunebaum E. EdU incorporation is an alternative non-radioactive assay to [3H]thymidine uptake for in vitro measurement of mice T-cell proliferations. J Immunol Methods. 2009;350:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He HJ, Zhu TN, Xie Y, Fan J, Kole S, Saxena S, Bernier M. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate inhibits interleukin-6 signaling through impaired STAT3 activation and association with transcriptional coactivators in hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31369–31379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu LJ, Yu MH, Huang CY, Niu LX, Wang YF, Wu CZ, Yang PM, Hu X. Isoprenylated flavonoids from Morus nigra and their PPAR γ agonistic activities. Fitoterapia. 2018;127:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iglesias-Ara A, Osinalde N, Zubiaga AM. Detection of E2F-induced transcriptional activity using a dual luciferase reporter assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1726:153–166. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7565-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarnow P, Bross S, Wollenberg L, Nakajima Y, Ohmiya Y, Tralau T, Luch A. A novel dual-color luciferase reporter assay for simultaneous detection of estrogen and aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2017;30:1436–1447. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.7b00076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao J, Tao J, Zhang N, Liu Y, Jiang M, Hou Y, Wang Q, Bai G. Formula optimization of the Jiashitang scar removal ointment and antiinflammatory compounds screening by NF-κB bioactivity-guided dual-luciferase reporter assay system. Phytother Res. 2015;29:241–250. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Wu X. Utilizing Matrigel Transwell invasion assay to detect and enumerate circulating tumor cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1634:277–282. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7144-2_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai H, Zhao X, Qin Y, Ding Y, Chen R, Li G, Labrie M, Ding Z, Zhou J, Hu J, et al. FAK-ERK activation in cell/matrix adhesion induced by the loss of apolipoprotein E stimulates the malignant progression of ovarian cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:32. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0696-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi W, Wang X, Ruan L, Fu J, Liu F, Qu J. MiR-200a promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition of endometrial cancer cells by negatively regulating FOXA2 expression. Pharmazie. 2017;72:694–699. doi: 10.1691/ph.2017.7649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao H, Qin X, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Lin J, Ting K, Chen F. Nell-1-ΔE, a novel transcript of Nell-1, inhibits cell migration by interacting with enolase-1. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:5725–5733. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong J, Wang Z. Analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor-induced cell motility by wound healing assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1652:159–163. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7219-7_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bedoya C, Cardona A, Galeano J, Cortés-Mancera F, Sandoz P, Zarzycki A. Accurate region-of-interest recovery improves the measurement of the cell migration rate in the in vitro wound healing assay. SLAS Technol. 2017;22:626–635. doi: 10.1177/2472630317717436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riis S, Newman R, Ipek H, Andersen JI, Kuninger D, Boucher S, Vemuri MC, Pennisi CP, Zachar V, Fink T. Hypoxia enhances the wound-healing potential of adipose-derived stem cells in a novel human primary keratinocyte-based scratch assay. Int J Mol Med. 2017;39:587–594. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck F. The role of Cdx genes in the mammalian gut. Gut. 2004;53:1394–1396. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.038240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizoshita T, Inada K, Tsukamoto T, Kodera Y, Yamamura Y, Hirai T, Kato T, Joh T, Itoh M, Tatematsu M. Expression of Cdx1 and Cdx2 mRNAs and relevance of this expression to differentiation in human gastrointestinal mucosa - with special emphasis on participation in intestinal metaplasia of the human stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:185–191. doi: 10.1007/PL00011741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suh E, Chen L, Taylor J, Traber PG. A homeodomain protein related to caudal regulates intestine-specific gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7340–7351. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.11.7340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bai YQ, Miyake S, Iwai T, Yuasa Y. CDX2, a homeobox transcription factor, upregulates transcription of the p21/WAF1/CIP1 gene. Oncogene. 2003;22:7942–7949. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raymond A, Liu B, Liang H, Wei C, Guindani M, Lu Y, Liang S, St John LS, Molldrem J, Nagarajan L. A role for BMP-induced homeobox gene MIXL1 in acute myelogenous leukemia and identification of type I BMP receptor as a potential target for therapy. Oncotarget. 2014;5:12675–12693. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rouhi A, Fröhling S. Deregulation of the CDX2-KLF4 axis in acute myeloid leukemia and colon cancer. Oncotarget. 2013;4:174–175. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan LH, Wei WY, Xie YB, Xiao Q. New insights into the functions and localization of the homeotic gene CDX2 in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3960–3966. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camilo V, Barros R, Celestino R, Castro P, Vieira J, Teixeira MR, Carneiro F, Pinto-de-Sousa J, David L, Almeida R. Immunohistochemical molecular phenotypes of gastric cancer based on SOX2 and CDX2 predict patient outcome. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:753. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Camilo V, Garrido M, Valente P, Ricardo S, Amaral AL, Barros R, Chaves P, Carneiro F, David L, Almeida R. Differentiation reprogramming in gastric intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia: Role of SOX2 and CDX2. Histopathology. 2015;66:343–350. doi: 10.1111/his.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schildberg CW, Abba M, Merkel S, Agaimy A, Dimmler A, Schlabrakowski A, Croner R, Leupold JH, Hohenberger W, Allgayer H. Gastric cancer patients less than 50 years of age exhibit significant downregulation of E-cadherin and CDX2 compared to older reference populations. Adv Med Sci. 2014;59:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cobler L, Pera M, Garrido M, Iglesias M, de Bolós C. CDX2 can be regulated through the signalling pathways activated by IL-6 in gastric cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:785–792. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang J, Li T, Gao C, Lv X, Liu K, Song H, Xing Y, Xi T. FOXO1 3′UTR functions as a ceRNA in repressing the metastases of breast cancer cells via regulating miRNA activity. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3218–3224. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liang WC, Fu WM, Wong CW, Wang Y, Wang WM, Hu GX, Zhang L, Xiao LJ, Wan DC, Zhang JF, et al. The lncRNA H19 promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition by functioning as miRNA sponges in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:22513–22525. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar MS, Armenteros-Monterroso E, East P, Chakravorty P, Matthews N, Winslow MM, Downward J. HMGA2 functions as a competing endogenous RNA to promote lung cancer progression. Nature. 2014;505:212–217. doi: 10.1038/nature12785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 47.Karreth FA, Tay Y, Perna D, Ala U, Tan SM, Rust AG, DeNicola G, Webster KA, Weiss D, Perez-Mancera PA, et al. In vivo identification of tumor-suppressive PTEN ceRNAs in an oncogenic BRAF-induced mouse model of melanoma. Cell. 2011;147:382–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karreth FA, Reschke M, Ruocco A, Ng C, Chapuy B, Léopold V, Sjoberg M, Keane TM, Verma A, Ala U, et al. The BRAF pseudogene functions as a competitive endogenous RNA and induces lymphoma in vivo. Cell. 2015;161:319–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Esposito F, De Martino M, D'Angelo D, Mussnich P, Raverot G, Jaffrain-Rea ML, Fraggetta F, Trouillas J, Fusco A. HMGA1-pseudogene expression is induced in human pituitary tumors. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:1471–1475. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1021520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poliseno L, Pandolfi PP. PTEN ceRNA networks in human cancer. Methods. 2015;77-78:1–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen J, Hu Q, Schrauder M, Yan L, Wang D, Medico L, Guo Y, Yao S, Zhu Q, Liu B, et al. Circulating miR-148b and miR-133a as biomarkers for breast cancer detection. Oncotarget. 2014;5:5284–5294. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nohata N, Hanazawa T, Enokida H, Seki N. microRNA-1/133a and microRNA-206/133b clusters: Dysregulation and functional roles in human cancers. Oncotarget. 2012;3:9–21. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo J, Zhou J, Cheng Q, Zhou C, Ding Z. Role of microRNA-133a in epithelial ovarian cancer pathogenesis and progression. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1043–1048. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.