A rapidly expanding body of research has indicated that perceived racial discrimination is a strong predictor of poor health and that this relation may be attributable, in part, to unhealthy behavior (Richman, Pascoe, & Lattanner, in press). For example, perceived racial discrimination has been associated with smoking (Bennett, Wolin, Robinson, Fowler, & Edwards, 2005; Landrine & Klonoff, 1996), increased alcohol use (Brown & Tooley, 1989; Sanders-Phillips, 1999), unhealthy eating (Pascoe & Richman, 2011), risky sex (Roberts et al., 2012), and sedentary life styles (Womack et al., 2014). In their meta-analysis of the literature on the discrimination - health behavior relation, Pascoe and Richman (2009) concluded that discrimination has a significant negative relation with health behavior, and that this relation is stronger for females than for males (r = −.26 vs. −.14).

Emotional Responses as Mediators

Internalizing reactions.

Recent examinations of mediators of the effects of discrimination on health behaviors and health outcomes has focused on the role of two different kinds of emotional responses to the stress induced by discrimination - internalizing (anxiety and depression) and externalizing (hostility and anger). Regarding the former, a study of Black parents and their children (part of the Family and Community Health Study [FACHS]) found that self-reports of discrimination were related to increases in anxiety and depression for both the parents and their children (Gibbons, Gerrard, Wills, Cleveland & Brody, 2004; see also Brown et al., 2000; Klonoff, Landrine, & Ulman, 1999). This relation has also been found in a recent experimental study showing that young Black adults who were excluded by Whites in an online game of Cyberball attributed that exclusion to racial discrimination and reported increases in depression (Stock et al., 2017). Importantly, internalizing affective responses have consistently been associated with decreases in health status, including chronic illnesses, physical limitations, poor immune functioning (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Robles, Glaser, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005), as well as risk for STIs (Roberts et al., 2012). In a prospective study, Schulz et al. (2006) found that increases in Black women’s reports of discrimination were associated with increases in their reports of depression and decreases in reports of their general health.

Externalizing reactions.

Not surprisingly, a number of prospective studies have shown that discrimination also elicits hostility and anger in Black Americans (Cleveland, 2003; Simons et al., 2006; Terrell, Miller, Foster, & Watkins 2006; see Pascoe & Richman, 2009, for a review). Once again, experimental studies have found similar results. Mendes and her colleagues manipulated social rejection by providing Black and White participants with bogus rejection feedback from other Black or White participants (e.g., “I would not like to be in a small class with the other subject”; “I would not like to get to know the other subject better”), and found that both Black and White participants who experienced out-group rejection reported increases in anger (Mendes, McCoy, Major, & Blascovich, 2008; cf. Jamieson, Koslov, Nock & Mendes, 2012).

Substance use.

Research has also demonstrated that anger and hostility mediate the relation between discrimination and substance use. For example, a study with Black women and their adolescent children in FACHS (Gibbons et al., 2010, Study 1) found that the women’s reports of discrimination were directly related to increases in their substance use (alcohol and drugs) five years later, and indirectly related to that substance use through increases in hostility. The adolescents’ data revealed a similar pattern: discriminatory experiences reported at age 10–11 were associated with increased anger in the adolescents at age 12–13, and this anger mediated increases in their self-reported substance use at age 15–16. Study 2 in that paper provided experimental evidence of the same relations. A sample of FACHS adolescents (mean age 18.5) was instructed (or not instructed) to imagine experiencing discrimination in a work-related situation. Relative to the controls, participants who imagined the discrimination scenario reported more anger and more depression / anxiety; they also reported more willingness to use drugs. However, only the anger and not the depression / anxiety mediated the discrimination → drug willingness relation in that group. Similar results were reported in another experimental study by Stock et al. (2017) with a different sample. Collectively, these studies suggest that different affective responses to the stress produced by discrimination may be associated with different health-relevant outcomes.

Differential Mediation

Social and health psychologists have provided direct evidence of different affective mediating pathways through which perceptions of discrimination turn into health behaviors, ultimately affecting health status (Major, Mendes, & Dovidio, 2013; Mendes et al., 2008). Very few of these studies, however, have adopted the perspective that stressors can elicit both internalizing and externalizing reactions simultaneously (cf., Carver, 2004; Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009), and that these processes affect health in different ways. Nonetheless, there is reason to expect that both internalizing and externalizing reactions to perceived racial discrimination can co-occur, and may be associated with different health outcomes.

Externalizing affective responses are more strongly related to risk-taking behaviors (Lerner & Keltner, 2001; Rydell et al., 2008), including substance use (Aklin, Moolchan, Luckenbaugh, & Ernst, 2009). There is also experimental evidence of this effect: Jamieson et al. (2012) found that the anger produced by other-race rejection was associated with more risk-taking in a card game. In contrast, internalizing responses are more strongly associated with avoidance of risky behaviors1 (Broman-Fulks, 2014; Giorgetta et al., 2012; Mitte, 2007). However they are also associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Moser et al., 2011; Mykletun et al., 2009; Rovner et al., 1991). These findings suggest that the relation between discrimination and both health status and health behavior may be explained by a “differential mediation” model - discrimination is associated with decreases in physical health and increases in health risk behaviors, with the former relation being mediated more by changes in internalizing responses, whereas the latter relation is mediated more by changes in externalizing responses. Analysis of four waves of data (covering eight years) from the Black women in FACHS supported this hypothesized mediational pattern (Gibbons et al., 2014). Discrimination was associated with increases in both internalizing and externalizing emotions, as well as an increase in alcohol use and a decrease in health status, all consistent with the literature. However, the prospective relation between discrimination and increased alcohol use was mediated by changes in externalizing, but not internalizing, whereas the relation between discrimination and decreases in health status was mediated by changes in internalizing, but not externalizing emotions.

Moderators of Responses to Racial Discrimination

Establishing moderators of health risk factors improves our understanding of disease etiology and has the potential of informing the development of efficacious interventions (MacKinnon & Luecken, 2008). Although many studies have examined various factors that may moderate the relation between perceptions of discrimination and health status and health-impairing behaviors, to our knowledge, none have examined potential moderators of the effects of emotional reactions to discrimination-induced stress on health status and health-related behaviors. The current study examined two hypothesized moderators of these effects.

Support networks.

Having social support networks, i.e., the presence or availability of friends and family members who can express concern and love, and provide coping assistance (Sarason et al., 1983), is widely accepted as beneficial for both physical and psychological health (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Cutrona, 1996; Thoits, 1995). This kind of social support appears to be especially important for Black women (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Lewis-Coles & Constantine, 2006; McLoyd, 1998). However, although it is commonly hypothesized that support networks are effective buffers of the link between discrimination and health status (e.g., Clark, 2003; Finch & Vega, 2003), the evidence of their efficacy is actually fairly weak (Brondolo et al., 2009; Pascoe & Richman, 2009). In this study, we test a specific version of the stress-buffering hypothesis: that support networks moderate the relation between internalizing reactions to discrimination and health status.

Avoidant coping.

Motivational models of alcohol use suggest that people generally have two related but specific reasons for substance use: to enhance positive affective states, and to reduce negative emotional states (Cooper et al., 2008; Cox & Klinger, 1988). The latter motive - a form of avoidant coping, i.e., removing oneself from experiencing or thinking about a stressful situation (Carver et al., 1989) - is not a significant buffer of the effect of discrimination on physical health (Pascoe & Richman, 2009). But, it is more likely to lead to alcohol consumption and alcohol problems, as well as other types of substance use (Aldridge-Gerry et al., 2011; Cooper, Russell, & George, 1988; Merrill & Thomas, 2013). More relevant to the current study, Gerrard et al. (2012) examined moderation of the relation between discrimination-based stress and alcohol use by avoidant coping. Two lab studies, using different manipulations of discrimination, demonstrated that the relation between discrimination and willingness to use alcohol and drugs was stronger for young Black adults reporting that they used more avoidant substance use-as-coping strategies. A third, survey study, involving analyses of several waves of data from FACHS young adults, showed the same effect over time on willingness to drink and also on self-reported drinking. Finally, recent research has also suggested that a combination of both of these moderators - having a weak support network and employing avoidant coping - interact to increase perceived stress (Chao, 2011).

Frequency of drinking vs. problematic drinking: A racial crossover.

Black adolescents in the U.S. start drinking later than White adolescents, and they are less likely to continue drinking into early adulthood (Malone, Northrup, Masyn, Lamis, & Lamont, 2012). However, this pattern changes in adulthood. Black adults who are heavy drinkers are more likely to continue heavy drinking after their early 20s (Costanzo et al., 2007), and perceived discrimination is a significant predictor of this trajectory (Madkour et al., 2015). More generally, among adult regular drinkers, Blacks are more likely than Whites to experience alcohol-related social and health problems (Godette, Headen & Ford, 2006; Keyes et al., 2012; Mulia, Ye, Greenfield & Zemore, 2009). Because of this distinction between drinking frequency and drinking consequences, in the current study, we chose to explore links from emotional reactions to discrimination to both frequency of drinking and problematic drinking.

The Current Study

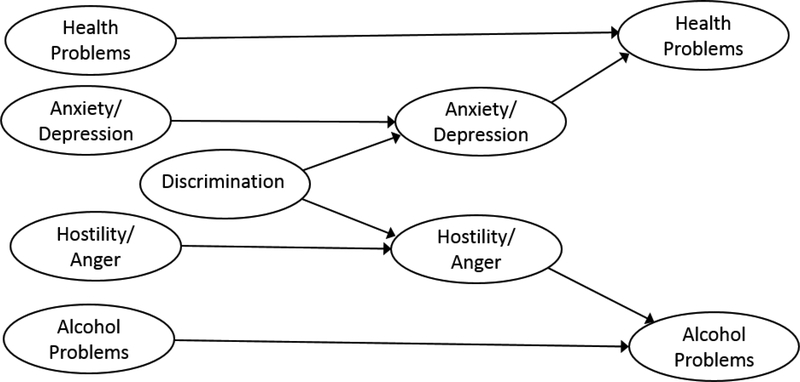

The goal of the current study was to expand existing research on differential mediation of discrimination effects through internalizing and externalizing emotional responses to long-term effects on health behavior (alcohol use) and health status. First, we sought to replicate the differential mediation effect (Gibbons et al., 2014) with new data collected when the FACHS women were three years older and their physical health had declined significantly (Figure 1 presents a heuristic model with the hypothesized pathways showing differential mediation). Second, unlike the previous study, which combined alcohol use and problematic drinking into one construct, we also examined differential mediation of paths to drinking frequency and the more consequential outcome, problematic drinking. Third, the current study tested the hypotheses that the link between internalizing responses to perceived discrimination and health status is moderated by the presence of support networks, whereas the link from externalizing responses to discrimination and frequency of drinking and problematic drinking is moderated by avoidant coping. Finally, we hypothesized that a combination of avoidant coping and poor social networks would be associated with problematic alcohol consumption (cf. Chao, 2011).

Figure 1.

Heuristic Model of the Differential Mediation Hypothesis(from Gibbons et al., 2014).

Methods

Sample

FACHS is an ongoing study of psychosocial factors related to the mental and physical health of Black families (Gerrard, Gibbons, Stock, Vande Lune & Cleveland, 2005; Gibbons, Stock, Vande Lune & Cleveland, 2004a). There were 889 families in the first wave (T1), half from Iowa and half from Georgia. Each family included a child who was in 5th grade at T1 and the child’s primary caregiver (PC). Most PCs were female (94%); 90% of them were the biological mothers of the children (other PCs included grandmothers, stepmothers, and foster parents). The current analyses were conducted on a subset of the PCs: those who self-identified as African American or Black, and provided data in all five waves of data collection; N = 508. The women’s mean age at T1 was 37 years (SD = 7.7); at T5, it was 48 (SD = 7.6). Their modal level of education was high school graduate; approximately 66% of them were single at T1. Retention across the five waves was > 65%.

Recruitment and Procedure

Families were recruited from small communities, suburbs, and small metropolitan areas, with mostly lower and middle class families. Of those families contacted, 72% provided data (the vast majority of those who declined cited the amount of time the interviews took - see below). Median family income for the families at T1 was $20,685/year ($31,297 in 2017 dollars); 33% of the families were living below the poverty line. For further description of the FACHS sample and recruitment, see Cutrona et al. (2005) and Gibbons et al. (2004b). All interviewers were Black. Interviews lasted ~ 3 hours and included a computer assisted personal interview (CAPI) as well as a structured psychiatric diagnostic assessment (the U. of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview [UM-CIDI]; Kessler, 1991). Participants received $100 at T1 to T3 and $125 at T4 and T5. Average time between T1 and T2 was 24 months; it was 36 months between each of the other waves. The research was approved by the IRBs at the universities involved; informed consent was obtained from participants at every wave.

Measures (Waves of data collection for each measure are listed in parentheses)

Perceived racial discrimination

(T2/T3) was assessed with a 13-item, modified version of the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). This measure, one of the most commonly used in discrimination research (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009), describes various discriminatory events and asks how often respondents have experienced each type of event due to their race; e.g., “How often has someone said something insulting to you just because you are African American?” (1 = never to 4 = several times; αs = .93 and .91). Lifetime discrimination measures like these are particularly useful for longitudinal studies (Williams & Mohammed, 2009), and appear to be more effective than daily discrimination measures at predicting health problems (Paradies, 2006; Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003). The 13 items were randomly parceled into three indicators of the latent construct.

Negative affect

(T1, T4) was assessed with five questions for depression: “During the past week, how much have you felt: hopeless / depressed / discouraged / like a failure / worthless for depression and tense / uneasy / keyed up for anxiety” (Cutrona et al., 2005). Each item included a 3-point scale: 1 = not at all to 3 = extremely (all four αs for both waves > .78). The negative affect latent construct had these two indicators (depression and anxiety).

Hostility / Anger

(T1, T4) was assessed with two sets of items from the UM-CIDI that reflect two separate components commonly used in the health literature (cf. Kamarck, Manuck, & Jennings, 1990): hostile behavior (aggression against others) and anger. Hostile behavior items included five types of anti-social behaviors (lifetime), which pertained to harming others (e.g., “Have you… been in physical fights? … threatened someone?” plus two items about violence against their partner, which were combined into one measure (total αs = .51 at T1 and .55 at T4). These six measures were then averaged to create one parcel of the latent construct. Anger was assessed with a single item: “You don’t get upset too easily” from 1 = strongly agree, to 4 = strongly disagree. Thus, once again, there were two indicators; in this case, one for hostile aggression and one for anger.

Alcohol use.

For the first model (a conceptual replication of Gibbons et al., 2014; see Figure 1), alcohol use was assessed with questions about drinking frequency and problems associated with alcohol consumption at T1 and T5. The second model separated the frequency and problematic consumption measures into two constructs at T1 and T5. At T1, frequency was assessed with two questions about drinking in the last 12 months (“How much alcohol have you typically consumed at each sitting during the last year,” and “In the past 12 months, did you have at least 1 drink… almost every day, 3 or 4 days a week, 1 or 2 days a week, 1 to 3 times a month, or less than once a month?” (α = .77). Problematic consumption at T1 was assessed with six questions from the UM-CIDI about experiencing problems (lifetime) due to alcohol use (no/yes): fighting, problems at work, trouble with friends or family, problems getting along with others, being arrested (e.g., DUI), and being harmed while under the influence (α = .84). The combined alcohol use scale at T1 had α = .81. At T5, alcohol frequency included five questions about consumption over the last 12 months: frequency of: drinking beer, wine, liquor, having 3 or 4 drinks in a row, and having 5 or more drinks in a row (α = .77). Problematic consumption at T5 included the six items from T1, plus four additional questions about problems, e.g., felt guilty about drinking, felt a need to cut down (α = .94). The T5 combined alcohol scale had α = .94.

Health status

(T1, T5) was assessed with two single items at T1: a) current overall health status: “In general, would you say your health is?” from 0 = excellent to 4 = poor (which has been shown to be a good predictor of both morbidity and mortality; Idler & Benyamini, 1997; Jylha, 2009; cf. Williams, Spencer, & Jackson, 1999); and b) “Have you had a serious illness or injury in the past year?” (no/yes). At T5, the same measure of current overall health status was used, but the serious illness or injury question (which was endorsed by few women) was replaced with a scale comprising five items assessing the extent to which current health status and / or pain interfered with physical functioning, e.g., limited climbing stairs, interfered with work; each scored from 1 = No, not limited at all, to 3 = Yes, limited a lot (Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996; α = .90). In addition, the health status questions included a number of chronic illnesses ever diagnosed by a doctor (e.g. high blood pressure, arthritis, asthma, diabetes; no / yes), and the number of prescription medications the participant takes or is supposed to take (total scale α = .78).

Support network

(T1) was assessed by four questions about close friends and relatives, i.e., “About how many close friends do you have?... How many of your relatives live less than 50 miles from your home?... How many of your partner’s relatives live less than 50 miles from your home?...” (all open answers, capped at a maximum of 11); “How often do you have contact with close friends, either in person, on the phone or by writing letters?” from 1 = “I have no close friends” to 7 = “every day”, responses to the questions were averaged (α = .51).

Avoidant coping

(T1) was assessed with four general questions about dealing with problems: “When you have a problem, you usually…. try to do things that will keep you from thinking about it…, try to forget about it… try to figure out the cause and do something about it…, talk to other people about it…”. Each item included a 4-point scale: 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree. Items were coded so that higher scores indicated a coping style focused more on avoidance and less on problem solving (α = .34).

Covariates

(T1)—Five variables that have been linked with physical health status and/or substance use were included as covariates: age, SES (income and education), negative life events (28-item checklist; e.g., close friend or relative died, relationship break-up), financial stress (6 items; e.g., ability to pay bills, buy clothing), and neighborhood risk (7 items; e.g., drinking in public, gang violence). Covariates and exogenous (T1) constructs were allowed to correlate, and the relations between all of the covariates and the endogenous constructs were estimated.

Results

The results are reported in four sections. The first section presents information on the outcome measures. Section two presents results from the first structural equation model (SEM), which examined whether the differential mediation reported in Gibbons et al. (2014) was replicated in the sample at T5 (when the women’s M age was 48 – three years older than in the outcome wave in the previous study). In section three, the alcohol use constructs were separated into those that assess frequency and those that assess problems related to drinking, and the mediation paths for each were examined separately (in the whole sample). Finally, the fourth section examines moderation of the paths from internalizing and externalizing to health status and alcohol outcomes by support networks and avoidant coping, employing multigroup SEMs to compare responses of women with high and low scores on these moderators.

Part 1: Health and Alcohol Outcomes

At T2/3,2 more than 90% of the sample reported experiencing some discrimination, and approximately 20% reported large amounts of discrimination. The most common health problems were pain interfering with activities (44%) and limitation of moderate activities (such as climbing stairs) due to health problems (35%). To examine change, repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted on the outcome measures that were available in both T1 and T5. Overall health status deteriorated significantly during this time period (p < .001), and reports of frequency of drinking increased, i.e., 20% reported more than minimal drinking at T1, whereas 33% did at T5 (p < .001). Direct comparisons between T1 and T5 problematic consumption were not possible because of the change in wording of items between these waves. Consistent with previous literature (Mulia et al., 2009), there were relatively few regular drinkers at T5 (< 20% drank every week or more) within that group, however, 60% of them reported at least one alcohol-related problem in the last year.

Part 2: Differential Mediation: A Replication Out to T5 (Whole Sample)

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) conducted to test the fit of the measurement model matched that in Gibbons et al. (2014) and provided good fit to the data: χ2 (145, N = 508) = 326.77, X2: df ratio= 2.25; CFI =.95, TLI = .91; RMSEA = .05.3 T2/3 discrimination was correlated with T4 negative affect and T4 hostility (rs = .18 and .13, ps < .005). In addition, both T4 negative affect and hostility were significantly correlated with T5 health status and alcohol use (rs from .12 to .26, ps < .01). Lagrange multipliers (modification indices) were used to detect any unspecified paths that could improve the fit of the model when moving from the CFA to the SEM. The SEM also fit the data well: χ2 (163, N = 508) = 358.10, X2: df ratio = 2.20; CFI = .94, TLI = .92; RMSEA = .05. Stability paths for internalizing and externalizing (T1 to T4) and for both outcome measures (T1 to T5) were moderate to strong (all rs > .35, ps < .001).

Consistent with the Gibbons et al. (2014) study, discrimination at T2/T3 was associated with increases in internalizing and externalizing at T4 (standardized coefficients: βs =.12 and .19, respectively, ps < .03). More important, T4 hostility was associated with change in alcohol use from T1 to T5 (β = .17, p = .01), and T4 negative affect was associated with change in health problems over the same period (β = .20, p < .01). The indirect path from discrimination to change in health problems through change in negative affect was also significant (β = .02, p = .05), and the indirect path from discrimination to change in alcohol use through change in hostility was marginal (β = .03, p = .08). In addition, a modification index called for a direct path from T2/3 discrimination to T5 health (a 6– to 9-year lag; β = .13, p = .01). With the exception of this direct path, all coefficients in this model are consistent with those in Gibbons et al. (2014); however, the indirect mediation of the discrimination to alcohol use by hostility -- for the entire sample -- was only marginal.

Part 3: Drinking Frequency vs. Drinking Problems: Whole Sample

The second model divided the alcohol questions into those assessing alcohol frequency and those assessing alcohol problems and tested the association of negative affect and hostility with changes in both of these new constructs. The CFA on the variables included in this model indicated that it fit the data well: χ2 (163, N = 508) = 358.30, X2: df ratio = 2.20; CFI = .95, TLI = .90; RMSEA = .05; as did the SEM: χ2 (191, N = 508) = 406.05, X2: df ratio = 2.13; CFI = .94, TLI = .91; RMSEA = .05. Once again, the correlations reveal moderate to strong stability of T1 to T4 or T5 assessments (8- and 11-year lags) of negative affect, hostility, health status, alcohol frequency, and alcohol problems (rs range from .30 to .44, ps < .005; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlations Among Measurement Variables for Moderation Structural Equation Model

| VARIABLE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 NEGATIVE AFFECT T1 | ||||||||||||

| 2 HOSTILITY/ANGER T1 | .23*** | |||||||||||

| 3 HEALTH PROBLEMS T1 | .26*** | .11* | ||||||||||

| 4 ALCOHOL FREQUENT USE T1 | .08 | .14*** | .06 | |||||||||

| 5 ALCOHOL PROBLEMS T1 | .25*** | .18*** | .13*** | .26*** | ||||||||

| 6 PERCEIVED RACIAL DISCRIMINATION T23 | .08 | .11* | .04 | .01 | .14*** | |||||||

| 7 NEGATIVE AFFECT T4 | .44*** | .23*** | .22*** | .07 | .21*** | .18*** | ||||||

| 8 HOSTILITY/ANGER T4 | .12*** | .36*** | .11* | .03 | .12** | .13*** | .28*** | |||||

| 9 HEALTH PROBLEMS T5 | .17*** | .05 | .43*** | -.02 | .15*** | .18*** | .26*** | .16*** | ||||

| 10 ALCOHOL FREQUENT USE T5 | .04 | .08 | -.10* | .33*** | .13*** | -.01 | .05 | .08 | -.06 | |||

| 11 ALCOHOL PROBLEMS T5 | .20*** | .12** | .06 | .27*** | .30*** | .07 | .22*** | .09* | .05 | .44*** | ||

| 12 SUPPORT NETWORK T1 | -.14*** | -.09* | -.03 | -.02 | -.07 | .02 | -.07 | -.05 | .00 | .02 | -.11* | |

| 13 AVOIDANT COPING T1 | .21*** | .09* | .19*** | .07 | .07 | -.16*** | .10* | .04 | .03 | .02 | .09* | -.10* |

Note: Higher scores indicate more of the construct.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .005

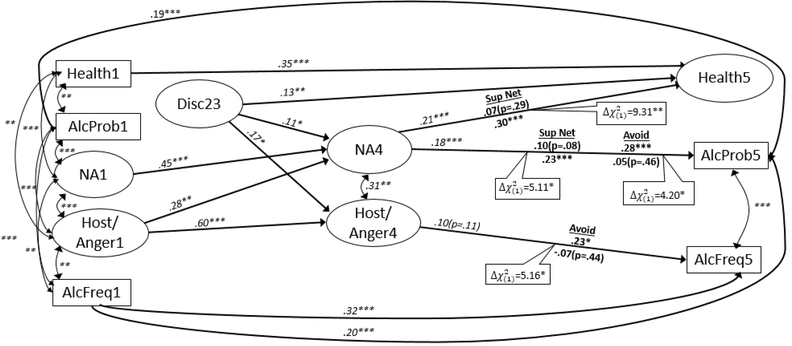

This model replicated the paths from discrimination to changes in internalizing and externalizing, and the path from internalizing to health status (coefficients for this model are presented in italics in Figure 2). Consistent with the correlations, internalizing was associated with problematic drinking (β = .18, p < .001), and the indirect path from discrimination to problematic drinking through negative affect was significant (β = .02, p = .05). In contrast, externalizing was only marginally associated with increases in frequency of drinking (β =.10, p =.11), and the indirect path from discrimination to alcohol frequency through hostility was not significant (β = .02, p = .19). Finally, as expected, the paths from externalizing to alcohol problems and from internalizing to alcohol frequency were not statistically significant (both ps > .65).

Figure 2.

Structural Equation Model of the Discrimination on Health Problems, Alcohol Frequency, and Alcohol Problems.

Note. Estimated path coefficients are completely standardized. Numbers in construct names indicate wave of measurement;

Disc = perceived racial discrimination; NA = anxiety and depression; Host/Anger = hostility/Anger

Heath = health problems; AlcFreq = alcohol frequency; AlcProb = alcohol problems

Bold coefficients are stacked on moderators (Sup Net = support networks, Avoid = Avoidant Coping), Above the line = High values/Below the line = Low Values

*p≤.05; **p.<.01; ***p<.0001.

Part 4: Moderation of the internalizing and externalizing responses to discrimination

Dichotomous variables were created using a median split for support network (0 = weaker, 1 = stronger), and avoidant coping (0 = less, 1 = more), and two “stacked” (multigroup) SEMs were performed, one for each moderator (see Figure 2). All paths were allowed to vary, except the stability paths. In this model both support network and avoidant coping significantly moderated two paths from T4 affective responses to T5 outcomes, i.e., there were statistically significant reductions in model fit when the two paths for each of the groups were constrained to be equal.

Support networks.

The path from T4 negative affect to T5 health status had coefficients that were significantly different for women with strong vs. weak support networks (Δχ2(1) = 9.31, p < .003). As expected, the association between T4 negative affect and T5 health problems was significant for women with weak support networks (β = .30, p < .01), but not for those with strong networks (β = .07, p = .29). Similarly, the association between T4 negative affect and T5 alcohol problems also varied as a function of support network (Δχ2(1) = 5.11, p = .02). The path was significant for women with weak networks (β = .23, p < .01), but was marginally significant for those who had stronger networks (β = .10, p = .08). Finally, the indirect paths from T2/3 Discrimination to both T5 health problems and T5 alcohol problems through negative affect were significant for the low support group (both ps < .05), but not for the high support group (both ps > .15)

Avoidant coping.

As indicated, the alpha for the avoidant coping scale was very low; so, even though the pattern on these moderation analyses was as hypothesized, caution is warranted in interpreting the results. The association between T4 hostility and T5 alcohol frequency did differ as a function of coping (Δχ2(1) = 5.16, p = .02), as it was significant for women who reported more avoidant coping (β = .23, p =.02), but not for those who reported less avoidant coping (β = −.07, p = .44). Similarly, the association between T4 negative affect and T5 alcohol problems also differed for the two groups (Δχ2(1) = 4.20, p = .04), and again, it was significant for women who reported more avoidant coping (β = .28, p < .01), but not for those who reported less avoidant coping (β = .05, p = .46). The indirect effect from T2/3 discrimination through negative affect to T5 alcohol problems was significant for the high avoidance group (p < .04), and the indirect path from T2/3 discrimination to alcohol frequency was marginal (p < .10). Neither of these indirect paths was significant for the low avoidance group (both ps > .45).

Avoidant coping and support networks.

Finally, to assess the combined effect of both moderators on the path from internalizing to problematic alcohol consumption, we conducted a regression analysis that included the interaction between support network and avoidant coping. The significant interaction indicated, as expected, that for those women who have a weak support network and a tendency to employ avoidant coping, discrimination was strongly predictive of more problematic drinking (β = .89, p = .002; cf. Chao, 2011).

Discussion

Emotional Responses to Discrimination

One goal of the current study was to further examine the differential mediation model (Gibbons et al., 2014), initially by extending it out to a later wave. In this new model, the effect of discrimination on anxiety and depression was again strong, as was the effect of these internalizing responses on health status. Similarly, the effect of discrimination on externalizing was also significant, as was the path from hostility and anger to the combined alcohol use measure. In short, with one exception, the results paralleled those from the earlier study, this time with outcomes three years later. The difference was that in this new model, the indirect path from discrimination through hostility to alcohol frequency was not significant (for the whole sample). Instead, these analyses revealed new evidence that the relations between both types of affective reactions to discrimination and health outcomes are moderated by different factors.

Coping

Results of the stacked model revealed moderation of the path from hostility to frequency of drinking by avoidant coping: Women who indicated they tend to deal with problems by avoiding thinking and/or doing something about it drank more often and reported more problematic drinking after experiencing discrimination than did women who did not report this coping style. This kind of coping style is not surprising, given that many of these women probably assumed there was little they could actually do about the stressor. Moreover, there is evidence that some Blacks engage in another form of avoidance, “discrimination denial” (Crosby, 1984; Ruggiero & Taylor, 1997) as a means of coping with the stress. In any case, the coping results are consistent with a large body of research suggesting that avoidant coping can be effective in the short run, but has negative effects on health behavior and health status in the long run (Ben-Zur, 2009; Suls & Fletcher, 1985; Wolf & Mori, 2009). The current data also suggest, however, that Black women who respond to discrimination with externalizing emotions, but do not engage in avoidant coping, may turn to alcohol to mute their discrimination-related stress without escalating to high levels of consumption or without experiencing alcohol-related problems.

Support

As noted in reviews of the relevant research (e.g., Brondolo et al., 2009; Pascoe & Richman, 2009), it has been assumed that support networks are effective buffers against the negative effect of perceived racial discrimination on physical health; however, evidence of the efficacy of this coping mechanism has been limited. This study does provide evidence of these network buffering effects: the women in this study who reported having strong support networks did not suffer the harmful effects of depression and anxiety on their health to the same extent that women with weak networks did; they were also largely protected from the effects of internalizing on alcohol problems. One important question that deserves further empirical attention is what types of social support (emotional, distraction, informational; cf. Cutrona, 1996) these women are receiving from their friends and family that is having this buffering effect, specifically with regard to their physical health and their health behavior.

Intervention Implications

The current study provides evidence of the utility of two potentially modifiable moderators of the effects of stress on health status and health behaviors—avoidant coping style and support networks. Given that coping mechanisms have been demonstrated to be responsive to intervention (Litt, Kadden, & Kabela, 2009; Merrill & Thomas, 2013; Vieten, Astin, Buscemi, & Galloway, 2010), and thus can influence decisions about stress reduction, future research should explore effective ways to produce these changes in coping style. One possibility suggested by recent research is that some Blacks respond to discrimination-based stress by increasing their levels of physical exercise (Corral & Landrine, 2012; Borrell et al., 2012). This type of “positive avoidance” might be particularly effective at tempering the negative emotional responses associated with a stressor that, realistically, cannot be addressed directly with most active coping strategies. FACHS research is examining this issue currently.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations of the research should be considered. First, as with many long-term prospective studies, some of the measures changed over time. The primary purpose of the T1 measures of health status and alcohol consumption in this study was to control for previous health behavior / conditions in the analyses; and the stability coefficients suggest they did this effectively. However, the fact that some of the items were not identical at T1 and T5 does limit comparisons of absolute amounts of change across time. Second, in spite of their face validity, the internal consistency of the moderator measures -- especially avoidant coping -- was low. This is a problem, and it suggests caution is warranted when interpreting the results. However, it is also a problem, in part, because low reliability tends to attenuate moderation effects, thereby potentially underestimating the relations that were found (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2002; Whisman & McClellan, 2005). Future research should employ more extensive coping and buffering measures than were available in this dataset.

Another issue to be considered is that the participants in this study were middle-aged Black women who lived in nonurban areas of two states; this raises issues of generalizability. In fact, there is reason to believe that Black men are more likely to respond to discrimination by externalizing and substance use (Cloninger, Sigvardsson, & Bohman, 1996). We did not have enough male PCs in FACHS to make these comparisons, however. Moreover, experiences of discrimination and reactions to it (including alcohol use) may vary as a function of minority status (Hatzenbuehler, in press) as well as geographical location (Gibbons et al., 2007). Future research should examine both men’s and women’s emotional reactions to discrimination and its impact on their health behavior and health status. Studies should also include other minority or stigmatized groups, and, to the extent possible, samples from other geographic areas.

Finally, the direct path from T2/3 discrimination to T5 health (p = .01) raises another issue to be considered in future research with new methods. The current study employed self-reports of health status and alcohol consumption. Self-reports of morbidity have been shown to be good predictors of mortality (perhaps better than physician diagnosis), especially among Black Americans (Ferraro & Farmer, 1996); self-reports of substance use have been widely accepted as accurate, including among Black Americans (Wills & Cleary, 1997). However, recent advances in assessment of biological markers of substance use and morbidity are beginning to establish a new standard for studies like this. For example, the use of DNA and methylation-based indices to assess substance use (Beach et al., 2015; Philibert et al., 2016), and measures of allostatic load to examine the toll of chronic perceived discrimination on the body (Brody et al., 2014) will open the door to new research that can supplement data from self-reports (see Mendes & Muscatell, in press, for a review). Such methods may address this potentially very important question of why discrimination appears to have a direct effect on physiological health that may not be mediated by changes in affect or cognitions (Brondolo, in press; Simons, Lei, Beach, Cutrona, Gibbons, & Philibert, in press).

Conclusion

Perceived racial discrimination is associated with increases in both internalizing and externalizing emotional responses, and these reactions, in turn, are associated with deterioration in health status and increases in unhealthy behavior (drinking frequency and problematic drinking). These relations between emotional response and health are buffered by the presence of support networks, and amplified by avoidant coping tendencies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants DA021898, DA018871, and MH062668.

Contributor Information

Meg Gerrard, Department of Psychological Sciences and Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InChip), University of Connecticut.

Frederick X. Gibbons, Department of Psychological Sciences and Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InChip), University of Connecticut

Mary Fleischli, InChip, University of Connecticut.

Carolyn Cutrona, Department of Psychology, Iowa State University.

Michelle Stock, Department of Psychology, The George Washington University.

References

- Aklin WM, Moolchan ET, Luckenbaugh DA, & Ernst M (2009). Early tobacco smoking in adolescents with externalizing disorders: Inferences for reward function. Nicotine Research, 11(6), 750–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge-Gerry AA, Roesch SC, Villodas F, McCabe C Leung QK, & Da Costa M (2011). Daily stress and alcohol consumption: Modeling between-person and within-person ethnic variation in coping behavior. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(1), 125–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Meeshanthini VD, Lei MK, Cutrona CE, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Philibert RA (2015). Methylomic aging as a window on lifestyle impact: Tobacco and alcohol alter the rate of biological aging. Journal of the American Genetics Society. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63, 2519–2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett G, Wolin K, Robinson E, Fowler S, & Edwards C (2005). Perceived racial/ethnic harassment and tobacco use among African American young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 95(2), 238–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zur H (2009). Coping styles and affect. International Journal of Stress Management, 16(2), 87. [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Kiefe CI, Siez-Roux AV, Williams DR, & Gordon-Larsen P (2013). Racial discrimination, racial/ethnic segregation, and health behaviors in the CARDIA study. Ethnicity & Health, 18(3), 227–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Lei M-K, Chae DH, Yu T, Kogan SM, & Beach SRH (2014). Perceived discrimination among African American adolescents and allostatic load: A longitudinal analysis with buffering effects. Child Development, 85, 989–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman-Fulks JJ, Urbaniak A, Bondy CL, & Toomey KJ (2014). Anxiety sensitivity and risk-taking behavior. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 27(6), 619–632. [Pubmed: 24559488] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E (in press). Racism and physical health: Biopsychosocial mechanisms In Major B, Dovidio JF, & Link BG (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Brady Ver Halen N, Pencille M, Beatty D, & Contrada RJ (2009). Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 64–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown F & Tooley J (1989). Alcoholism in the black community In Lawson GW & Rockville AW, MD: Aspen: Lawson; (Eds.), Alcoholism and Substance Abuse in Special Populations (pp. 115–130). [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, Williams DR, Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, Sellers SL, & Brown K (2000). Being black and feeling blue: The mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race & Society, 2, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Carver SC & Harmon-Jones E (2009). Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications. Psychological Bulliten, 135(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, & Weintraub JK (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RCL (2011). Managing stress and maintaining well-being: Social support, problem-focused coping, and avoidant coping. Journal of Counseling and Development, 89, 338–348. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R (2003). Self-reported racism and social support predict blood pressure reactivity in Blacks. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 25(2), 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland D (2003). Beating the odds: Raising academically successful African American males. Journal of Men’s Studies, 12, 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR Sigvardsson S, & Bohman M (1996). Type I and type II alcoholism: An update. Alcohol Health & Research World. 20(1), 18–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, & Aiken LS (2002). Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd Edition. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Krull JL, Agocha VB, Flanagan ME, Orcutt HK, Grabe S, & Jackson M (2008). Motivational pathways to alcohol use and abuse among Black and White adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 485–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, & George WH (1988). Coping, expectancies, and alcohol abuse: A test of social learning formulations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 218–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral I & Landrine H (2012). Racial discrimination and health-promoting vs damaging behaviors among African-American adults. Journal of Health Psychology, 17(8), 1176–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo PR, Malone PS, Belsky D, Kertesz S, Pletcher M, & Sloan FA (2007). Longitudinal differences in alcohol use in early adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(5), 727–737. [PubMed: 17690807]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MW & Klinger E (1988). A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(2), 168–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby F (1984). The denial of personal discrimination. American Behavioral Scientist, 27, 371–386. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE (1996). Social Support in Couples. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Brown PA, Clark LA, Hessling RM, & Gardner KA (2005). Neighborhood context, personality, and stressful life events as predictors of depression among African American women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS & Kemeny ME (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 355–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro K & Farmer M (1996). Double jeaoprady, aging as leveler, or persistent health inequality? A longitudinal analysis of White and Black Americans. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 51B(6), S319–S328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, & Vega WA (2003). Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of immigrant health, 5(3), 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll CT, Lamberty G, McAdoo HP, Crnis K, Wasik BH, & Vazquez Garcia H (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Stock ML, Roberts ME, Gibbons FX, O’Hara RE, Weng C-Y, & Wills TA (2012). Coping with racial discrimination: The role of substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 550–560. [PubMed: 22545585]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Stock (Gano) ML, Vande Lune L, & Cleveland MJ (2005). Images of Smokers and Willingness to Smoke among African American Pre-adolescents: An Application of the Prototype/Willingness Model of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior to Smoking Initiation. Pediatric Psychology, 30, 305–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Etcheverry PE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng C-Y, Kiviniemi M, & O’Hara RE (2012). Exploring the link between racial discrimination and substance use: What mediates? What buffers? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(5), 785–801. [PubMed: 20677890]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G (2004a). Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 517–529. [PubMed: 15053703]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Vande Lune LS, Wills TA, Brody G, & Conger RD (2004b). Context and cognition: Environmental risk, social influence, and adolescent substance use. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1048–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Kingsbury JH, Weng C-Y, Gerrard M, Cutrona CE, Wills TA, Stock ML, (2014). Effects of perceived racial discrimination on health status and health behavior: A differential mediation hypothesis. Health Psychology, 33, 11–19. [Pubmed: 24417690]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Reimer RA, Gerrard M, Yeh H-C, Houlihan A, Cutrona CE, Simons RL, & Brody GH (2007) Rural – Urban differences in substance use among African American adolescents. Journal of Rural Health, 23, 22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgetta C, Grecucci A, Zuanon S, Perini L, Balestrieri M, Bonini N, … & Brambilla P (2012). Reduced risk-taking behavior as a trait feature of anxiety. Emotion, 12(6), 1373–1383. [Pubmed: 22775123]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godette DC, Headen S, Ford CL (2006). Windows of opportunity: Fundamental concepts for understanding alcohol-related disparities experienced by young Blacks in the United States. Prevention Science, 7(4), 377–387. DOI: 10.1007/s11121-006-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (in press). Structural stigma and health In Major B, Dovidio JF, & Link BG (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL & Benyamini Y (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 21–37. [PubMed: 9097506]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson JP, Koslov K, Nock MK, & Mendes WB (2012). Experiencing discrimination increases risk taking. Psychological science, 24(2), 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylha M (2009). What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Social Science and Medicine, 69, 307–316. [PubMed: 19520474] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarck TW, Manuck SB, & Jennings JR (1990). Social support reduces cardiovascular reactivity to psychological challenge: a laboratory model. Psychosomatic Medicine, 52(1), 42–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC (1991). UM-CIDI Training Guide for the National Survey of Health and Stress, 1991–1992 [Software Manual]. Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Liu XC, & Cerda M (2012). The role of race/ethnicity in alcohol-attributable injury in the United States. Epidemiologic Reviews, 34, 89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonnoff EA, Landrine H, & Ulman JB (1999). Racial discrimination and psychiatric symptoms among blacks. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 5, 329–339. [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H & Klonoff EA (1996). The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology, 22(2), 144–168. DOI: 10.1177/00957984960222002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JS & Keltner D (2001). Fear, anger, and risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1), 146 [Pubmed: 11474720]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Coles MAEL & Constantine MG (2006). Racism-related stress, Africultural coping, and religious problem-solving among African Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12(3), 433–443. [PubMed: 16881748]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, & Kabela-Cormier E, (2009). Individualized assessment and treatment program for alcohol dependence: Results of an initial study to train coping skills. Addiction, 104, 1837–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP & Luecken LJ (2008). How and for whom? Mediation and moderation in health psychology. Health Psychology, 27 (2Suppl), 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madkour AS, Jackson K, Wang H, Miles TT, Mather F, Shankar A (2015). Perceived discrimination and heavy episodic drinking among African-American youth: Differences by age and reason for discrimination. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(5), 530–536. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Mendes WB, & Dovidio JF (2013). Intergroup relations and health disparities: A social psychological perspective. Health Psychology, 32(5), 514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone PS, Northrup TF, Masyn KE, Lamis DA, & Lamont AE (2012). Initiation and persistence of alcohol use in the United States Black, Hispanic, and White male and female youth. Addictive Behaviors, 37(3), 299–305. DOI: 10.1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist, 53, 185–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes WB, Major B, McCoy S, & Blascovich J (2008). How attributional ambiguity shapes physiological and emotional responses to social rejection and acceptance. Journal of personality and social psychology, 94(2), 278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes WB & Muscatelli K (in press). Emotions and emotion regulation as mediators of the relationship between stigma and health In Major B, Dovidio JF, & Link BG (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE & Thomas SE (2013). Interactions between adaptive coping and drinking to cope in predicting naturalistic drinking and drinking following a lab-based psychosocial stressor. Addictive Behaviors, 38(3), 1672–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitte K (2007). Anxiety and risk decision-making: The role of subjective probability and subjective cost of negative events. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 243–253. [Google Scholar]

- Moser DK, McKinley S, Riegel B… Baker H, & Dracup K (2011). Relationship of persistent symptoms of anxiety to morbidity and mortality outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(9), 803–809. DOI: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182364992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, & Zemore SE (2009). Disparities in alcohol-related problems among White, Black and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(4), 654–662. DOI: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mykletun A, Bjerkeset O, Overland S, Prince M, Dewey M, & Stewart R (2009). Levels of anxiety and depression as predictors of mortality: The HUNT study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(2), 118–125. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y (2006). A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(4), 888–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Richman LS (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531 [Pubmed: 19586161]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Richman LS (2011). Effect of discrimination on food decisions. Self and Identity, 10(3), 396–406. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman L (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 135(4), 531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philibert R, Hollenbeck N, Andersen E, McElroy S, Wilson J, Vercande K, Beach SRH, Osborn R, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Wang K (2016). Reversion of AHRR Demethylation is a Quantitative Biomarker of Smoking Cessation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman LS, Pascoe EA, & Lattanner M (in press). Interpersonal Discrimination and Physical Health In Major B, Dovido JF, & Link BG (Ed.), Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health. New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ME, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Weng C-Y, Murry VM, Simons LG, Simons RL, & Lorenz FO (2012). From racial discrimination to risky sex: Prospective relations involving peers and parents. Developmental Psychology, 48, 89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Glaser R, & Kiecolt-Glaser JK (2005). Out of balance: A new look at chronic stress, depression, and immunity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rovner BW, German PS, Brant LJ, Clark R, Burton L, & Folstein MF (1991). Depression and mortality. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 265(8), 993–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KM, & Taylor DM (1997). Why minority group members perceive or do not perceive the discrimination that confronts them: The role of self-esteem and perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 373–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydell RJ, McConnell AR, & Mackie DM (2008). Consequences of discrepant explicit and implicit attitudes: Cognitive dissonance and increased information processing. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1526–1532. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Phillips K (1999). Ethnic minority women, health behaviors, and drug abuse: A continuum of psychosocial risks. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12, 174–195. DOI: 10.1007/s10567-009-0053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Levine HM, Basham RB, et al. (1983). Assessing social support: The Social Support Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Gravlee CC, Williams DR, Israel B, Mentz G, Rowe Z (2006). Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: Results from a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1265–1270. [PubMed: 16735638]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Drummund H, Stewart E, Brody GH, Gibbons FX, & Cutrona CE (2006). Supportive parenting moderates the effect of discrimination upon anger, hostile view of relationships, and violence among African American boys. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 373–389. [PubMed: 17240926]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons R.l., Lei M-K, Beach SRH, Cutrona CE, Gibbons FX, & Philibert RA (in press). Ratio of inflammatory to antiviral Social Science and Medicine [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock ML, Gibbons FX, Beekman JB, Williams KD, Richman LS, & Gerrard M (2017). Racial (versus self) affirmation as protective mechanisms against the effects of racial exclusion on substance use vulnerability among African American young adults. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stock ML, Gibbons FX, Walsh LA, Gerrard M (2011). Racial Identification, Racial discrimination, and Substance Use Vulnerability among African American Young Adults. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 1349–1361. [PMID: 21628598]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, & Fletcher B (1985). The relative efficacy of avoidant and nonavoidant coping strategies: a meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 4, 249–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suitt KG, Castro Y, Caetano R, & Field CA (2015). Predictive utility of alcohol use disorder symptoms across Race/Ethnicity. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 56, 61–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell F, Miller AR, Foster K, & Watkins CE (2006). Racial discrimination-induced anger and alcohol ruse among black adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 41(163), 485–492. [PubMed: 17225663]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What Next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, (Extra Issue: Forty Years of Medical Sociology: The State of the Art and Directions for the Future), 53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieten C, Astin JA, Buscemi R, & Galloway GP (2010). Development of an acceptance-based coping intervention for alcohol dependence relapse prevention. Substance Abuse, 3, 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, & Keller SD (1996). A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34(3), 220–233. [Pubmed: 8628042]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA & McClelland GH (2005). Designing, testing and interpreting moderator effects in family research. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR & Mohammed SA (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of behavioral medicine, 32(1), 20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2003). Racial / ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 93(2), 200–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Spencer M, & Jackson JS (1999). Race Stress and Physical Health: The Role of Group Identity In Contrada RJ & Ashmore RD (Ed.), Self, Social Identity and Physical Health: Interdisciplinary Explorations (pp. 71–100). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, & Cleary SD (1997). The validity of self-reports of smoking: analyses by race / ethnicity in a school sample of urban adolescents. American journal of public health, 87(1), 56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ & Mori DL, (2009). Avoidant coping as a predictor of mortality in veterans with end-stage renal disease. Health Psychology, 28, 330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womack VY, Ning H, Lewis CE, Loucks EB, Puterman E, Reis J, Siddique J, Sternfeld B, Van Horn L, & Carnethon MR (2014). Relationship between perceived discrimination and sedentary behavior in adults. American Journal of Health Behavior, 38(5), 641–6419. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.5.1. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]