Abstract

Purpose:

Male urinary incontinence (UI) is thought to be infrequent. We sought to describe the prevalence of UI in a male treatment-seeking cohort enrolled in the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN).

Materials and Methods:

The inclusion/exclusion criteria, including men with prostate cancer or a neurogenic bladder, have been previously reported. LURN participants prospectively completed questionnaires regarding lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and other clinical variables. Men were grouped based on type of incontinence (1=non-UI; 2=post-void dribbling [PVD] only; 3=UI). Comparisons were made using analysis of variance and multivariable regression.

Results:

Among 477 men, 24% reported non-UI, 44% PVD only, and 32% UI. Black men and those with sleep apnea were more likely to be in the UI group compared with the non-UI group (odds ratio [OR]=3.2, p=0.02 and OR=2.73, p=0.003, respectively). UI was associated with significantly (p<0.001) higher bother compared to those without leakage. Compared to men without UI and men with PVD only, men with UI were significantly (p<0.01) more likely to report higher scores (more severe symptoms) on patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) questionnaires regarding bowel issues, depression, and anxiety, compared to those without UI.

Conclusions:

UI is common among treatment-seeking men. This is concerning because the guideline-recommended questionnaires for assessing male LUTS do not query for UI. Thus, clinicians may be missing an opportunity to intervene and improve patient care. This provides a substantial rationale for a new or updated symptom questionnaire that provides a more comprehensive symptom assessment.

Keywords: male, urinary incontinence, treatment-seeking, lower urinary tract dysfunction, patient questionnaire

INTRODUCTION

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common complaint that is thought to be significantly more prevalent in the female population, with an estimated prevalence up to 55%. UI can be categorized as urgency UI (UUI), stress UI (SUI), and mixed UI (MUI), in which both SUI and UUI are present. The International Continence Society has defined post-void (or post-micturition) dribbling (PVD)/post-void urinary incontinence (PV-UI) as a separate symptom associated with the phenomena of involuntary loss of urine immediately after a person has finished passing urine.1 Urinary leakage is extremely bothersome, usually associated with anxiety and depression, causes a decreased quality of life (QOL), and is a significant economic burden.2–5 However, because UI can be embarrassing and there is a perception that it is a normal and untreatable part of aging, not everyone with UI seeks treatment. This may be particularly relevant to the male population, where UI is historically thought to be infrequent.

In men, the prevalence of UI and PVD is largely unknown. Most previous studies evaluating UI prevalence have been conducted in women. Few studies in men distinguished between different types of UI. Prior studies of community-dwelling men, including the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey, Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC), and Epidemiology of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (EpiLUTS) studies, reported prevalence of UI in men ranging from 5.3%-45.8%.6 Among men with UI in these cohorts,1.2%-48.6% were UUI, 0.8%-12.5% SUI, 1.0%-15.4% MUI, and 2.9%-59% other UI, including PVD.6 Subsequent evaluation of the BACH cohort demonstrated that 8.7% of men reported PVD.7 In EPIC, 16.9% of men reported post-micturition symptoms; in EpiLUTS, PVD constituted 93.0% of the other incontinence group.8

The frequency of UI is unknown among men who actively seek treatment. The prevalence and types of UI in care-seeking men may differ from that of community-based men, and characterization of care-seeking men would be extremely relevant for their care. We sought to assess the prevalence and characteristics of care-seeking men with and without UI and its subtypes, and to examine the relationships with medical comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, sleep apnea, bowel symptoms, sexual functioning, anxiety, depression, stress).

METHODS

Study Design and Population

The goal of the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN) is to phenotype men and women with LUTS in order to develop improved clinical tools and treatments. Men and women in the LURN Observational Cohort Study9 were recruited from tertiary referral centers between January 2015-January 2017; however, only male participants are included in this analysis.10 Briefly, all consenting participants were adults (≥18 years) presenting to a LURN physician as new or existing patients with at least one urinary symptom identified based on the LUTS Tool.11 The exclusion criteria have previously been reported.10 Men with prostate cancer, including those with low-risk disease, were excluded as to remove potential confounding of LUTS by a pelvic malignancy. Data collection at the baseline visit included a standard clinical exam, medical history, and patient-reported urinary symptoms, pelvic floor symptoms, psychological symptoms, and QOL.

Measures

The LUTS Tool11 (Lower Urinary Tract Symptom [LUTS] Tool, Version 1.0. Copyright 2007 by Pfizer, Inc. Used with permission.) is a 44-item questionnaire assessing the frequency and bother of LUTS. Seven questions regarding incontinence (Questions 16a-g: “How often in the past week have you (a) leaked urine just after you have finished urinating? (b) leaked urine in connection with a sudden need to rush to urinate? (c) leaked urine in connection with laughing, sneezing, or coughing? (d) leaked urine in connection with physical activities, such as exercising or lifting heavy objects? (e) leaked urine while you are sleeping? (f) leaked urine during sexual activity? and (g) leaked urine for no reason?”) and one question regarding terminal dribble (Question 5: “During the past week, how often have you had a trickle or dribble at the end of your urine flow?”) were used to categorize men into UI, PVD only, and non-UI groups. Responses of “rarely” or “never” on all eight questions were classified as “non-UI”; responses of “sometimes” or greater on terminal dribble or leaked-after-voiding questions without indications of other incontinence symptoms were classified as “PVD only”; and responses of “sometimes” or greater on at least one other symptom of incontinence were classified as “UI”.

In addition to the LUTS Tool, participants completed the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI);12 Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measures of constipation, diarrhea, bowel incontinence, depression, and anxiety;13 International Index of Erectile Dysfunction (IIEF);14 Perceived Stress Scale (PSS);15 and Childhood Traumatic Events Scale.16 PROMIS13 measures were administered via short forms scored as T-scores normalized to a reference population (mean=50, standard deviation [SD]=10 by definition), with the exception of bowel incontinence, for which there were not enough items to convert to the T-score metric. The Childhood Traumatic Events Scale was collapsed into a summary measure indicating whether or not the participant had experienced any trauma.

Statistical Methods

Complete responses to the eight questions required for UI grouping were required for study inclusion. Demographic and clinical data were missing <1%. Questionnaire data were missing 3%-8%, except for the AUA-SI, which was missing for 12% of the cohort. Analyses of a given measure were used only in participants for which the measure could be scored according to validated guidelines.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the LURN male cohort are shown using means and SDs for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Tests for group differences were performed using chi-square and non-parametric analysis of variance (ANOVA; Kruskal-Wallis tests). Similar descriptive statistics and statistical tests were calculated for each physical and psychological measure. The PROMIS measures are presented as continuous measures and percentage exhibiting severe symptoms, defined as greater than one SD above the population mean (i.e., T-scores of >60).

Multivariable multinomial models were fitted. Candidate covariates included age, race, body mass index (BMI), education, employment status, smoking status, diabetes, sleep apnea, Functional Comorbidity Index (FCI),17 and LURN site. Multivariable linear regression was used to explore adjusted associations between measures of fecal incontinence, sexual function, and psychological health using the same set of predictors. Model selection was guided by the method of best subsets,18 and final model determination incorporated clinical expertise and judgement. All p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false-discovery rate correction.19 Analyses were completed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Four-hundred-seventy-seven of 519 men enrolled in the LURN Observational Cohort were included. The mean age was 60.9±13.3 years. The cohort was mostly Caucasian (80%), educated (60% had a bachelor’s degree or higher), and either employed full-time (38%) or not employed/not looking for work (49%, Table 1). About half of subjects reported being current or former smokers (46%), 26% had a diagnosis of sleep apnea, and 18% were diabetic. The average FCI17 was 2.1±1.8.

Table 1:

Descriptive characteristics of male LURN participants

| Overall (n=477) | UIα (n=150) | PVDβ (n=211) | non-UIγ (n=116) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or N (%) | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Mean (SD) or N (%) | ||

| Age | 60.9 (13.3) | 63.5 (11.5) | 57.9 (14.1) | 63.1 (12.8) | 0.001 |

| Race | 0.42 | ||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0% | |

| Asian | 4% | 5% | 3% | 4% | |

| Black | 10% | 16% | 8% | 8% | |

| White | 80% | 73% | 83% | 83% | |

| Other | 5% | 5% | 5% | 4% | |

| Unknown | 0% | 1% | 0% | 1% | |

| Education | 0.17 | ||||

| < HS diploma/GED | 3% | 1% | 4% | 4% | |

| HS diploma/GED | 10% | 11% | 10% | 10% | |

| Some college/tech school - no degree | 19% | 23% | 20% | 13% | |

| Associate’s degree | 7% | 6% | 10% | 4% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 24% | 25% | 25% | 22% | |

| Graduate degree | 36% | 33% | 32% | 47% | |

| Employment status | 0.39 | ||||

| Employed part-time | 10% | 11% | 9% | 9% | |

| Employed full-time | 38% | 32% | 43% | 37% | |

| Unemployed (looking for work) | 3% | 3% | 4% | 2% | |

| Not employed (not looking for work) | 49% | 54% | 44% | 52% | |

| BMI | 29.7 (5.7) | 30.7 (6.3) | 29.1 (4.8) | 29.3 (6.2) | 0.08 |

| <25 | 20% | 19% | 17% | 26% | 0.02 |

| 25-30 | 40% | 33% | 48% | 34% | |

| >30 | 41% | 48% | 35% | 41% | |

| Current or former smoker | 46% | 51% | 46% | 41% | 0.31 |

| Diabetic | 18% | 27% | 13% | 18% | 0.01 |

| Sleep apnea | 26% | 36% | 23% | 19% | 0.01 |

| Functional comorbidity index | 2.1 (1.8) | 2.5 (1.9) | 2.0 (1.7) | 1.9 (1.7) | 0.03 |

| PVR (ml, median, IQR) | 27 (0-82) | 28.5 (0-79) | 30 (14-90) | 21 (0-62) | 0.13 |

| Facility | 0.002 | ||||

| A | 12% | 7% | 14% | 16% | |

| B | 20% | 27% | 11% | 28% | |

| C | 19% | 17% | 20% | 19% | |

| D | 14% | 15% | 14% | 15% | |

| E | 19% | 17% | 24% | 14% | |

| F | 15% | 17% | 17% | 9% | |

p-value from chi-square or non-parametric ANOVA test of at least one pairwise difference between the three groups.

Responded sometimes, often, or almost always on at least 1 of 6 LUTS Tool questions related to incontinence (excludes question related to PV-UI).

Responded sometimes, often, or almost always to PVD and/or PV-UI question and never or rarely to remaining 6 LUTS Tool questions related to incontinence.

Responded never or rarely to all 7 questions related to incontinence and 1 question related to PVD on LUTS Tool.

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; BMI, body mass index; GED, general educational development; HS, high school; IQR, interquartile range; LURN, Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; PVD, post-void dribbling; PVR, post-void residual; SD, standard deviation; UI, urinary incontinence.

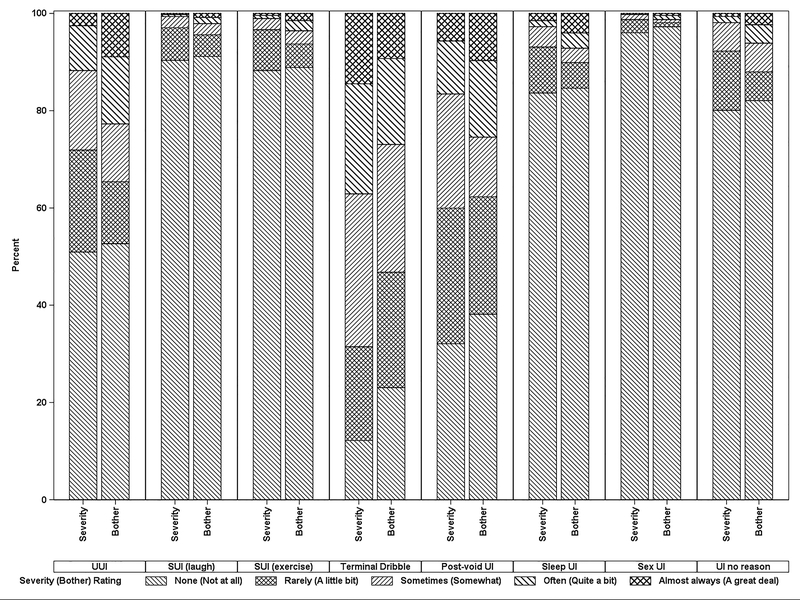

UI was reported in half of the men (51%). PVD and UUI were most common, occurring in 41% and 29% of men, respectively (Figure 1), while SUI was less common (3%-4%). PVD and UUI were most bothersome, with 39% and 35% reporting to be at least somewhat bothered, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Distribution of responses to LUTS Tool questions related to UI and PVD

Categorization into incontinence subgroups revealed 116 males without UI or PVD (24%), 211 PVD only (44%), and 150 UI (32%). Compared with other groups, the PVD only group was younger (mean 57.9±14.1 years, p=0.001), while the UI group was more likely to have comorbidities, such as obesity (48%, p=0.02), diabetes (27%, p=0.01), and obstructive sleep apnea (36%, p=0.01). Fifty percent of black participants were in the UI group, compared with 29% of white participants and 35% of participants of “other” race (p=0.07). The UI group was more likely to report urinary urgency (86%) and leakage due to urgency (87%, Table 2). PROMIS constipation and diarrhea scores were close to population means for all groups, although higher in the UI group compared with the non-UI and PVD only groups (p=0.02 and p=0.03, respectively). Elevated scores on the constipation scale were more common in the UI group (13%) compared with the PVD only (7%) and non-UI (4%) groups (p=0.07).

Table 2:

LUTS, bowel, and psychological symptoms in men in the LURN cohort

| Overall (n=477) | UIα (n=150) | PVDβ (n=211) | non-UIγ (n=116) | p-value* | Adjusted p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUTS | ||||||

| AUA-SI | 13.7 (7.0) | 16.3 (7.3) | 14.3 (6.4) | 9.3 (5.3) | <0.001 | - |

| AUA-SI voiding | 6.7 (4.9) | 7.8 (5.3) | 7.6 (4.7) | 3.8 (3.6) | <0.001 | - |

| AUA-SI storage | 7.0 (3.3) | 8.6 (3.1) | 6.7 (3.1) | 5.5 (3.1) | <0.001 | - |

| AUA-SI QOL | 3.7 (1.4) | 4.3 (1.2) | 3.7 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.5) | <0.001 | - |

| Feelings of urgency | 57% | 87% | 50% | 31% | <0.001 | - |

| Leakage due to feelings of urgency | 28% | 89% | 0% | 0% | <0.001 | - |

| Bowel Symptoms | ||||||

| PROMIS GI bowel incontinence (raw scale) | 4.8 (1.8) | 5.4 (2.3) | 4.5 (1.4) | 4.5 (1.5) | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| PROMIS GI diarrhea (T-score) | 46.5 (7.5) | 47.9 (8.0) | 46.5 (7.3) | 45.0 (6.9) | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| PROMIS GI diarrhea (T-score) > 60 | 4% | 6% | 4% | 3% | 0.52 | - |

| PROMIS GI constipation (T-score) | 48.6 (7.9) | 50.5 (7.9) | 48.2 (7.8) | 47.0 (7.4) | 0.002 | 0.01 |

| PROMIS GI constipation (T-score) > 60 | 8% | 13% | 7% | 4% | 0.07 | - |

| Erectile Functioning | ||||||

| IIEF | 15.5 (11.3) | 12.6 (10.9) | 17.2 (11.0) | 15.9 (11.6) | 0.002 | 0.17 |

| Moderate/severe dysfunction (IIEF < 17) | 53% | 65% | 46% | 50% | 0.004 | - |

| Psychological Symptoms | ||||||

| PROMIS depression (T-score) | 47.6 (8.3) | 50.4 (8.8) | 47.3 (7.9) | 44.4 (7.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PROMIS depression (T-score) > 60 | 8% | 15% | 6% | 4% | 0.002 | - |

| PROMIS anxiety (T-score) | 47.9 (8.9) | 50.4 (9.8) | 47.7 (8.2) | 45.1 (7.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PROMIS anxiety (T-score) > 60 | 9% | 17% | 6% | 3% | <0.001 | - |

| Perceived stress scale | 10.9 (7.0) | 13.0 (7.2) | 10.7 (6.9) | 8.4 (5.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Childhood traumatic events scale | 65% | 66% | 67% | 59% | 0.42 | - |

| Childhood traumatic sexual experience | 7% | 10% | 5% | 7% | 0.39 | - |

p-value from chi-square or non-parametric ANOVA test of at least one pairwise difference between the three groups

Responded sometimes, often, or almost always on at least 1 of 6 LUTS Tool questions related to incontinence (excludes question related to PV-UI).

Responded sometimes, often, or almost always to PVD and/or PV-UI question and never or rarely to remaining 6 LUTS Tool questions related to incontinence.

Responded never or rarely to all 7 questions related to incontinence and 1 question related to PVD on LUTS Tool.

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; AUA-SI, American Urological Association Symptom Index; GI, gastrointestinal; IIEF, International Index of Erectile Dysfunction; LURN, Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; PROMIS, patient-reported outcomes measurement information system; PVD, post-void dribbling; QOL, quality of life; UI, urinary incontinence

Sexual functioning was impaired in the cohort on average, with mean scores in the moderate dysfunction range (mean±SD =15.5±11.3). Erectile function was worse in the UI group (mean=12.6), with 65% reporting moderate or severe dysfunction (IIEF <17, p <0.01).

PROMIS depression and anxiety scores, on average, were close to the normative population mean of 50, with less than 10% overall reporting elevated depression or anxiety scores, defined as T-scores >60 (one SD above population mean scores). Elevated depression and anxiety were more common in the UI group, with 15% and 17% reporting scores above 60, respectively, compared with 3%-6% in the PVD only and non-UI groups (p ≤0.001). PSS scores were also higher in the UI group (means, 13.0 [UI], 10.7 [PVD only], 8.4 [non-UI], p <0.001).

Significant predictors of the UI group included age, race, sleep apnea, and clinical site (Table 3). The odds of being in the PVD only group compared with the non-UI group were 3% lower per year increase in age (odds ratio [OR]=0.97, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.95-0.99), whereas black participants had three times higher odds of being in the UI group compared with the non-UI group (OR=3.20, 95% CI=1.35-7.62). Diagnosis of sleep apnea also increased the odds of being in the UI group compared with the non-UI group (OR=2.73, 95% CI=1.51-4.95).

Table 3:

Associations between demographic and clinical participant characteristics and urinary symptom group – results from multivariable multinomial logistic regression*

| Incontinence Group (ref=non-UI) | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | FDR p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| PVD | 0.97 | (0.95-0.99) | 0.004 | 0.008 | |

| UI | 1.01 | (0.98-1.03) | 0.576 | 0.632 | |

| Race (ref=white) | 0.055 | 0.085 | |||

| Black | PVD | 1.54 | (0.62-3.80) | 0.350 | 0.410 |

| UI | 3.20 | (1.35-7.62) | 0.008 | 0.017 | |

| Other race | PVD | 0.79 | (0.33-1.90) | 0.600 | 0.651 |

| UI | 1.35 | (0.55-3.27) | 0.511 | 0.572 | |

| Sleep apnea | 0.002 | 0.005 | |||

| PVD | 1.44 | (0.80-2.61) | 0.224 | 0.278 | |

| UI | 2.73 | (1.51-4.95) | <.001 | 0.003 |

Also adjusted for LURN site.

Abbreviations: FDR, false discovery rate; LURN, Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network; PVD, post-void dribbling; UI, urinary incontinence

After adjustment for the factors listed above, all significant differences between the urinary symptom groups remained statistically significant, except for differences in IIEF (Table 2; see Supplemental Table S1 for full model results). For all other measures, differences between UI and non-UI groups were significant; however, PVD only and non-UI groups showed no significant differences. Average estimated scores for UI compared with non-UI groups were 0.75 units higher for bowel incontinence, 2.41 units higher for diarrhea scale, and 3.00 units higher for constipation scale. Depression scores were 4.80 units higher in the UI group; anxiety scores were higher by a similar magnitude.

DISCUSSION

Half of men with LUTS who sought care at tertiary referral urology clinics reported some form of urinary leakage. Most commonly reported were UUI and PVD. In comparison to prior community-dwelling male studies,6,20, 21 there is a significantly higher prevalence of UI among men who seek clinical care for LUTS (Supplemental Figure S1). A likely explanation for the increased frequency of UI in our study relates to patient care-seeking behaviors. EpiLUTS data suggest that only a relatively small proportion of patients actively seek care for LUTS (ranging from 5.6%-29.1%, based upon LUTS symptom).8 However, LURN only included patients who presumably were bothered enough to seek care, supported by the high level of bother reported in the current study (Figure 1). In addition, previous studies conducted within the LURN demonstrate a relationship between symptom bother/severity and treatment-seeking behaviors.22

The association between race and UI is supported by several studies,20, 23 including the overactive bladder (OAB)-POLL, which24 demonstrated that black men had a significantly higher prevalence of UUI than other racial groups (10% vs. 6%, respectively). The current results also highlight other self-reported comorbidities that have been previously associated with UI, including sleep apnea. Historically thought to contribute only to nocturia, several recent studies have suggested that sleep disturbance is also associated with many daytime LUTS.25, 26 Secondary analyses of the EpiLUTS data demonstrated that patients with sleep apnea are 1.6 times more likely to experience UI compared to men without sleep apnea.11 Although the mechanisms that link UI and sleep apnea are unknown, it potentially opens an opportunity for a non-pharmacologic therapy for UI (e.g., pressure airway systems).

The physiology of urologic and gastrointestinal function is known to be interrelated. Crosstalk between neural pathways in the pelvic organs is necessary for the routine mediation of bladder, bowel, and sexual function.27, 28 This crosstalk also provides a pathway for abnormal function of these organs, with the potential for dysfunction of one pelvic organ leading to functional changes in another organ system. The results of this study support this theory of increasing frequency of bowel dysfunction (specifically constipation) in men with UI.

The associations between UI groups and measures of psychosocial health likely reflect the large psychologic impact of urinary leakage; however, no causal relationships can be determined from this observational study. EpiLUTS also demonstrated a high frequency of anxiety and depression among men with UI.3 These findings were consistent with other studies demonstrating higher anxiety and depression rates among patients with UI.29, 30 The direction of the relationship(s) between UI and mental health are as yet unknown and may be bidirectional. Additional research is warranted to further define these relationships and potentially exploit novel opportunities for intervention.

We identified a relationship between increased LUTS and PVD compared to men without UI. This supports previous findings demonstrating that PVD is more prevalent in men with voiding and storage symptoms.7 Other comorbidities, including bowel dysfunction, anxiety, and perceived stress, were also increased in this group compared with the non-UI group (Table 2). While the exact etiology of PVD remains unknown, these factors may provide insight into its pathophysiology. Further studies aimed at pinpointing the mechanisms underlying PVD are required.

The results of this study should be evaluated in the context of its limitations. The prevalence of UI in this study may have been underestimated since many patients with SUI were excluded from the study due to history of prostate cancer. We presented self-reported symptoms from the LUTS Tool. However, patients reporting these symptoms did not present with a chief complaint of all these symptoms; it is possible incontinence was not the primary reason for seeking care. Therefore, presence of UI may ultimately not be the most clinically-significant symptom that motivated their visit. Many patients in this study had previously undergone medical or surgical intervention for their LUTS before presenting to tertiary referral centers. As such, the impact of these previous interventions on UI remains to be determined. Comparison between LURN and other previous study cohorts may be limited by administered questionnaires. The treatment-seeking cohort in LURN is distinct from community populations, in that urinary symptoms that drive men to seek care may be unique and especially bothersome.

CONCLUSION

UI is a common symptom among men presenting at urology clinics. This is particularly concerning because the recommended and most commonly-used questionnaire for assessing male LUTS in the United States is the International Prostate Symptom Score/AUA-SI.12 This questionnaire does not assess for UI or PVD and, therefore, may be associated with a false negative impression that urinary leakage is not present or problematic for patients. UI and PVD are bothersome for all patients and associated with significantly decreased health-related QOL.3, 4, 7 This report provides a substantial rationale for a new or updated symptom questionnaire that provides a more comprehensive assessment. Capturing UI and PVD information and assessing for the presence of other related comorbidities (e.g., sleep apnea, diabetes, BMI, anxiety) will have the potential to significantly improve current clinical practices and treatments for men presenting with LUTS. Based upon these associations, clinicians should consider screening for incontinence and LUTS among men with these comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This is publication number 5 of the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN).

This study is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases through cooperative agreements (grants DK097780, DK097772, DK097779, DK099932, DK100011, DK100017, DK097776, DK099879).

Research reported in this publication was supported at Northwestern University, in part, by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant Number UL1TR001422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The following individuals were instrumental in the planning and conduct of this study at each of the participating institutions:

Duke University, Durham, North Carolina (DK097780): PI: Cindy Amundsen, MD, Kevin Weinfurt, PhD; Co-Is: Kathryn Flynn, PhD, Matthew O. Fraser, PhD, Todd Harshbarger, PhD, Eric Jelovsek, MD, Aaron Lentz, MD, Drew Peterson, MD, Nazema Siddiqui, MD, Alison Weidner, MD; Study Coordinators: Carrie Dombeck, MA, Robin Gilliam, MSW, Akira Hayes, Shantae McLean, MPH

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA (DK097772): PI: Karl Kreder, MD, MBA, Catherine S Bradley, MD, MSCE, Co-Is: Bradley A. Erickson, MD, MS, Susan K. Lutgendorf, PhD, Vince Magnotta, PhD, Michael A. O’Donnell, MD, Vivian Sung, MD; Study Coordinator: Ahmad Alzubaidi

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL (DK097779): PIs: David Cella, Brian Helfand, MD, PhD; Co-Is: James W Griffith, PhD, Kimberly Kenton, MD, MS, Christina Lewicky-Gaupp, MD, Todd Parrish, PhD, Jennie Yufen Chen, PhD, Margaret Mueller, MD; Study Coordinators: Sarah Buono, Maria Corona, Beatriz Menendez, Alexis Siurek, Meera Tavathia, Veronica Venezuela, Azra Muftic, Pooja Talaty, Jasmine Nero. Dr. Helfand, Ms. Talaty, and Ms. Nero are at NorthShore University HealthSystem.

University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI (DK099932): PI: J Quentin Clemens, MD, FACS, MSCI; Co-Is: Mitch Berger, MD, PhD, John DeLancey, MD, Dee Fenner, MD, Rick Harris, MD, Steve Harte, PhD, Anne P. Cameron, MD, John Wei, MD; Study Coordinators: Morgen Barroso, Linda Drnek, Greg Mowatt, Julie Tumbarello

University of Washington, Seattle Washington (DK100011): PI: Claire Yang, MD; Co-I: John L. Gore, MD, MS; Study Coordinators: Alice Liu, MPH, Brenda Vicars, RN

Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis Missouri (DK100017): PI: Gerald L. Andriole, MD, H. Henry Lai; Co-I: Joshua Shimony, MD, PhD; Study Coordinators: Susan Mueller, RN, BSN, Heather Wilson, LPN, Deborah Ksiazek, BS, Aleksandra Klim, RN, MHS, CCRC

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Kidney, Urology, and Hematology, Bethesda, MD: Project Scientist: Ziya Kirkali MD; Project Officer: John Kusek, PhD; National Institutes of Health Personnel: Tamara Bavendam, MD, Robert Star, MD, Jenna Norton

Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, Data Coordinating Center (DK097776 and DK099879): PI: Robert Merion, MD, FACS; Co-Is: Victor Andreev, PhD, DSc, Brenda Gillespie, PhD, Gang Liu, PhD, Abigail Smith, PhD; Project Manager: Melissa Fava, MPA, PMP; Clinical Study Process Manager: Peg Hill-Callahan, BS, LSW; Clinical Monitor: Timothy Buck, BS, CCRP; Research Analysts: Margaret Helmuth, MA, Jon Wiseman, MS; Project Associate: Julieanne Lock, MLitt

Heather Van Doren, MFA, senior medical editor with Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, provided editorial assistance on this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M et al. : The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn, 21: 167, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sexton CC, Coyne KS, Thompson C et al. : Prevalence and effect on health-related quality of life of overactive bladder in older americans: results from the epidemiology of lower urinary tract symptoms study. J Am Geriatr Soc, 59: 1465, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyne KS, Kvasz M, Ireland AM et al. : Urinary incontinence and its relationship to mental health and health-related quality of life in men and women in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Eur Urol, 61: 88, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang DH, Colayco D, Piercy J et al. : Impact of urinary incontinence on health-related quality of life, daily activities, and healthcare resource utilization in patients with neurogenic detrusor overactivity. BMC Neurol, 14: 74, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yehoshua A, Chancellor M, Vasavada S et al. : Health Resource Utilization and Cost for Patients with Incontinent Overactive Bladder Treated with Anticholinergics. J Manag Care Spec Pharm, 22: 406, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markland AD, Goode PS, Redden DT et al. : Prevalence of urinary incontinence in men: results from the national health and nutrition examination survey. J Urol, 184: 1022, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maserejian NN, Kupelian V, McVary KT et al. : Prevalence of post-micturition symptoms in association with lower urinary tract symptoms and health-related quality of life in men and women. BJU Int, 108: 1452, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sexton CC, Coyne KS, Kopp ZS et al. : The overlap of storage, voiding and postmicturition symptoms and implications for treatment seeking in the USA, UK and Sweden: EpiLUTS. BJU Int, 103 Suppl 3: 12, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang CC, Weinfurt KP, Merion RM et al. : Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network. J Urol, 196: 146, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron AP, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Smith AR et al. : Baseline lower urinary tract symptoms in patients enrolled in the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN): a prospective, observational cohort study. J Urol, In press, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khullar V, Sexton CC, Thompson CL et al. : The relationship between BMI and urinary incontinence subgroups: results from EpiLUTS. Neurourol Urodyn, 33: 392, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr., O’Leary MP et al. : The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol, 148: 1549, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A et al. : The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol, 63: 1179, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G et al. : The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology, 49: 822, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R: A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav, 24: 385, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pennebaker JW, Susman JR: Disclosure of traumas and psychosomatic processes. Soc Sci Med, 26: 327, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C et al. : The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol, 58: 595, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrell FE: Regression modeling strategies: With applications to linear modesl, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York, NY: Springer, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Society. Series B (Methodological), 57: 289, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tennstedt SL, Link CL, Steers WD et al. : Prevalence of and risk factors for urine leakage in a racially and ethnically diverse population of adults: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Am J Epidemiol, 167: 390, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S et al. : Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol, 50: 1306, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffith JW, Messersmith EE, Gillespie BW et al. : Reasons for Seeking Clinical Care for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: A Mixed-Methods Study. J Urol, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Kopp ZS et al. : Racial differences in the prevalence of overactive bladder in the United States from the epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. Urology, 79: 95, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Bell JA et al. : The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and overactive bladder (OAB) by racial/ethnic group and age: results from OAB-POLL. Neurourol Urodyn, 32: 230, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helfand BT, Lee JY, Sharp V et al. : Associations between improvements in lower urinary tract symptoms and sleep disturbance over time in the CAMUS trial. J Urol, 188: 2288, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helfand BT, McVary KT, Meleth S et al. : The relationship between lower urinary tract symptom severity and sleep disturbance in the CAMUS trial. J Urol, 185: 2223, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ustinova EE, Fraser MO, Pezzone MA: Cross-talk and sensitization of bladder afferent nerves. Neurourol Urodyn, 29: 77, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan SA, Dmochowski R, Cash BD et al. : Systematic review of the relationship between bladder and bowel function: implications for patient management. Int J Clin Pract, 67: 205, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim JR, Bak CW, Lee JB: Comparison of anxiety between patients with mixed incontinence and those with stress urinary incontinence. Scand J Urol Nephrol, 41: 403, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melville JL, Delaney K, Newton K et al. : Incontinence severity and major depression in incontinent women. Obstet Gynecol, 106: 585, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.