Key Points

Question

Does the frontalis myocutaneous transposition flap (FMTF) represent a good alternative for the reconstruction of forehead defects?

Finding

In this case series of 12 patients with large, deep forehead defects secondary to Mohs surgery reconstructed using the FMTF, all had satisfactory cosmetic and functional results and there were no postoperative complications.

Meaning

The FMTF is a useful alternative because it is richly vascularized by the frontalis muscle or its fascia, thus permitting a random design and a long and narrow shape that allows primary closure of the donor site and a 1-stage reconstruction of large forehead defects.

This case series of 12 patients with large, deep forehead defects secondary to Mohs surgery assesses whether the frontalis myocutaneous transposition flap represents a good alternative for the reconstruction of forehead defects.

Abstract

Importance

Forehead reconstruction after Mohs surgery has become a challenge for dermatology surgeons, and achieving an excellent cosmetic and functional result is imperative in this location.

Objective

To highlight the utility of a frontalis myocutaneous transposition flap (FMTF) for forehead reconstruction after Mohs surgery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Surgical technique case series including 12 patients with large forehead defects recruited between January 2010 and June 2017 at the Dermatology Department of the University Clinic of Navarra, Spain. All patients underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer (5 basal cell carcinomas, 4 melanomas, 2 squamous cell carcinomas, and 1 adnexal tumor) located on the forehead (8 paramedian, 2 midline, and 2 lateral subunits) resulting in defects ranging from 9 to 28 cm2 in size.

Intervention

Mohs micrographic surgery followed by FMTF. Taking into account the defect’s size and location, a lateral lobulated flap is designed with an inferior pedicle and incision lines are made vertically to the hairline containing part of the frontalis muscle or its fascia. The flap swings into the primary defect and direct closure of the donor site is achieved. Additional corrections for removing skin folds or a guitar-string suture can be made.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Absence of acute complications and achievement of high aesthetic and functional goals in postoperative follow-up.

Results

Satisfactory cosmetic and functional results were achieved for all 12 patients (7 men and 5 women; mean age, 62.7 years [range, 47-86 years]) and there were no postoperative complications. All the myocutaneous flaps survived without any acute complications, such as episodes of local bleeding, infection, flap margin necrosis, or congestion. Postoperative follow-up ranged from 6 months to 3 years. No patient needed scar revision. Six patients presented with paresthesia in areas of the forehead and scalp. Sensory recovery tended to improve over time, and paresthesia gradually decreased, disappearing in 5 of 6 cases after 12 months. In 3 patients there was a minimal hair transposition that required laser treatment.

Conclusions and Relevance

The FMTF provides a simple method for 1-stage reconstruction of large forehead defects as an alternative to classic advancement flaps.

Introduction

Large defects on the forehead can often be complicated to reconstruct because of excessive tension or risk of permanent brow elevation. Diverse options for the management of forehead defects exist. Primary closure is not considered amenable for large defects.1 Healing of forehead defects by secondary intention can produce good results, especially in the temple region, but not in the median or lateral forehead.2 Skin grafts3 cannot be used in deep defects exposing the outer table and also have disadvantages such as mismatches of depth, texture, and color.

Various designs of local flaps can provide an ideal option.4 Unilateral U-plasty and bilateral H-plasty are the most frequently used advancement flaps for forehead defects,5,6,7 but they are not a good option in patients with horizontally large wounds. Transposition flaps have classically been avoided because of the immobile nature and convexity of the forehead.

Our objective was to determine whether transposition flaps that incorporate the underlying muscle, myocutaneous flaps, are a useful alternative for forehead reconstruction. Herein we highlight the utility of a frontalis myocutaneous transposition flap (FMTF) for reconstruction of post–Mohs surgery large forehead defects.

Methods

Patients

Twelve patients (7 men and 5 women; mean age, 62.7 years [range, 47 to 86 years]) presented with different forms of skin cancer (5 basal cell carcinomas, 4 melanomas, 2 squamous cell carcinomas, and 1 adnexal tumor) that necessitated treatment with Mohs surgery on the forehead (Table). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Clinic of Navarra, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Table. Patient, Skin Cancer, and Defect Characteristics.

| ID No./Age, y/Sex | Neoplasm | Forehead Location | Defect Size, cm | Periosteal Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/80s/F | Melanoma | Paramedian medium | 3.0 × 3.5 | No |

| 2/50s/M | Melanoma | Midline inferior | 3.0 × 4.0 | No |

| 3/60s/M | BCC | Paramedian medium | 3.0 × 5.0 | Yes |

| 4/50s/M | SCC | Lateral inferior | 4.0 × 6.0 | Yes |

| 5/70s/M | Melanoma | Paramedian medium | 4.0 × 4.5 | No |

| 6/70s/F | BCC | Lateral inferior | 6.0 × 4.0 | Yes |

| 7/70s/M | BCC | Paramedian inferior | 3.5 × 6.0 | Yes |

| 8/50s/F | Adnexal tumor | Paramedian inferior | 3.0 × 4.0 | Yes |

| 9/70s/M | BCC | Paramedian medium | 3.0 × 3.0 | No |

| 10/60s/F | Melanoma | Midline inferior | 4.5 × 5.0 | No |

| 11/40s/F | BCC | Paramedian superior | 3.0 × 6.5 | Yes |

| 12/70s/M | SCC | Paramedian medium | 7.0 × 4.0 | Yes |

Abbreviations: BCC, basal cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

We divided the forehead into the midline (between the medial brows) and the paramedian (from midline to the midbrow) and lateral (from midbrow to the upper temple) subunits. The area from the glabella inferiorly to the scalp superiorly was then also divided into 3 subunits, inferior, medium, and superior. Most lesions (n = 8) were located in the paramedian (Table).

Surgical Technique

Mohs micrographic surgery was performed under local anesthesia of the area with bupivacaine hydrochloride, 0.5%, and tumor-free margins were achieved, resulting in full-thickness defects ranging from 9 to 28 cm2 in size. In 7 patients the periosteum was included. The authors elected to perform an FMTF for reconstruction of such defects. First, the individual forehead was carefully explored in each patient by laterally pinching with fingers possible donor sites and checking that their primary closure would be possible. The donor flap was oriented perpendicularly to the horizontal axis of the defect. A superiorly based donor site was used in all cases. Preoperative precise measurements of the flap length required were made in an attempt to avoid hair transposition. The flap was incised and broadly undermined at the level of the frontalis muscle to ensure adequate perfusion through subcutaneous vessels. Following hemostasis, closure of the donor site defect was achieved directly with clamps. The flap was transposed to the defect approximately 90° and secured with Novosyn sutures and the skin closed with silk 6-0 sutures.

To reduce the surgical defect prior to flap movement, a guitar-string suture was performed in all cases. These vertical dermal-subcutaneous sutures originate in the depth of the wound and roll toward the surface, reenter the opposite side of the wound in the dermis, and roll deep, thus creating uniform tension across the wound and significantly decreasing the size of the defect.8 An aesthetic correction could be made as well when the flap swings into the primary defect and a skin fold appears in the inner corner of the pedicle. The epidermis and superficial dermis should be removed to avoid this fold, but the rest of the layers maintained to ensure vascular supply of the FMTF. The surgical technique is illustrated in Figure 1 and the Video.

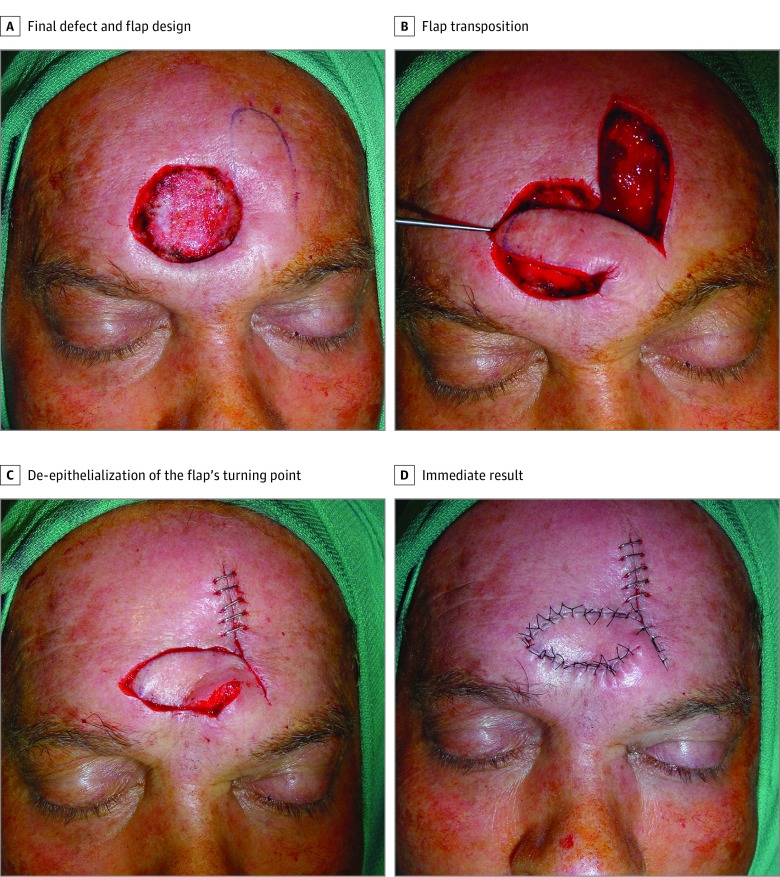

Figure 1. Frontalis Myocutaneous Transposition Flap (FMTF) Surgical Technique .

A, Patient 2, showing final defect after reexcision of positive margins. B, A lobulated FMTF is designed perpendicularly to the horizontal axis of the defect. C, Flap swings into the primary defect and donor site closure is achieved with metallic staples. The epidermis and superficial dermis were removed in the flap’s turning point. D, Result immediately after suturing the flap.

Video. Frontalis Myocutaneous Transposition Flap Surgical Technique.

Results

All the myocutaneous flaps survived without any acute complications, such as episodes of local bleeding, infection, flap margin necrosis, or congestion. Postoperative follow-up ranged from 6 months to 3 years. High aesthetic and functional goals—such as raising the eyebrows symmetrically, as well as the aesthetic placement of the brows—were achieved in all patients. No patient needed scar revision. Six patients presented with paresthesia in areas of the forehead and scalp. Sensory recovery tended to improve over time, and paresthesia gradually decreased, disappearing in 5 of 6 cases after 12 months. In 3 patients there was a minimal hair transposition that required laser treatment. Six months’ follow-up result of 1 patient is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Clinical Photographs Before and After Surgery.

A, A man in his 50s (patient 2) with midline inferior forehead melanoma (0.35 mm Breslow). B, Appearance 6 months after surgery.

Discussion

Following Mohs surgery, large defects on the forehead can often be complicated to surgically reconstruct, and a satisfactory result is imperative in this aesthetic unit. Simple or double advancement flaps are described in the literature as those most frequently performed for the forehead.5,6,7

We present a series of 12 patients with full-thickness defects including part of the frontalis muscle or its fascia and reaching the periosteum. An FMTF was performed, achieving excellent cosmetic and functional outcomes. In the FMTF design, some caveats are worthy of mention. First, primary closure of the donor site determines the flap’s maximum width, so each patient should be carefully examined to ensure that there is a sufficient quantity of remaining tissue by pinching the skin. Second, the increased vascular supply by the muscle allows a narrower base. Third, a guitar-string suture could be performed to reduce superior-to-inferior surgical defect distance and to improve flap matching. Finally, the skin fold caused by the 90° transposition movement can be superficially removed at the same surgical stage.

The principle of the FMTF consists of its thickness containing part of the frontalis muscle or its fascia, which ensures vascular supply and allows a long and narrow design that makes the primary closure of the donor site possible. The forehead has a rich vascularization with an extensive anastomotic network that allows the use of axial pattern flaps, without named arteries. Various designs can be implemented to achieve eyebrow and hairline symmetry and to carefully place suture lines within relaxed tension lines when possible.

The forehead flap is a workhorse for reconstruction of large full-thickness nasal defects. It is characterized by its dependability, consistent anatomy, and excellent texture match. For years, 180° transposition paramedian forehead flaps based on supratrochlear or supraorbital supply have been performed in a 2-stage surgical procedure. In the patients in the present study, the axial pattern flap guarantees excellent viability despite the fact that the length of the flap exceeds its width several times,9 and permits a single-stage reconstruction based on a 90° transposition movement.

Curiously, the dermatologic and plastic surgery literature does not describe the frontal transposition flap as a common alternative in forehead defects. Recently a modified Banner transposition flap for central forehead reconstruction has been described,10 which supports the robustness of our surgical technique. Other surgical options previously reported for repairing bone-exposed scalp or forehead defects include various random or pedicled local flaps, bilateral symmetric transposition flaps, subgaleal-subperiosteal flaps with split-thickness skin grafts, tissue expansion, or microvascular free tissue transfers.11,12,13,14

Limitations

Several limitations are present. This study is limited by a small sample size. The study was not powered to detect comparisons among various surgical techniques. This was a single-center case series.

Conclusions

The FMTF can be performed as an alternative to advancement flaps and provides a simple 1-stage surgical technique with excellent cosmetic results. This repair represents a useful and simple option for the reconstruction of large and deep horizontally oriented forehead defects.

References

- 1.Tajirian A, Tsui M. Central forehead reconstruction with a simple primary vertical linear closure. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9(8):47-49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker GD, Adams LA, Levin BC. Secondary intention healing of exposed scalp and forehead bone after Mohs surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121(6):751-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han S-K, Yoon W-Y, Jeong S-H, Kim W-K. Facial dermis grafts after removal of basal cell carcinomas. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23(6):1895-1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redondo P. Geometric reconstructive surgery of the temple and lateral forehead: the best election for avoiding a graft. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(11):1553-1560.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=18798749&dopt=Abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angelos PC, Downs BW. Options for the management of forehead and scalp defects. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2009;17(3):379-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hicks DL, Watson D. Soft tissue reconstruction of the forehead and temple. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2005;13(2):243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson MD, Hamilton GS III. Scalp and forehead defects in the post-Mohs surgery patient. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017;25(3):365-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redondo P. Guitar-string sutures to reduce a large surgical defect prior to skin grafting or flap movement. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(1):69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skaria AM. The median forehead flap reviewed: a histologic study on vascular anatomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(5):1231-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hankinson A, Holmes T. Repair of defects of the central forehead with a modified banner transposition flap. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(3):459-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verdolini R, Clayton N, Lowry CL. Case report and video demonstration of bilateral symmetric transposition flap to treat a challenging basal cell carcinoma on the forehead. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(suppl 1):105. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussain W, Hafiji J, Salmon P. Frontalis-based island pedicle flaps for the single-stage repair of large defects of the forehead and frontal scalp. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(4):771-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osorio M, Moubayed SP, Weiss E, Urken ML. Management of a nonhealing forehead wound with a novel frontalis-pericranial flap and a full-thickness skin graft. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(11):2456-2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim MC, Ko YI, Shim HS. Reconstruction of scalp and forehead defect with local transposition split skin flap and remnant full-thickness skin graft. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(10):1436-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]