In this cross-sectional study, the authors describe their findings of reliable systematic reviews that support topics likely to be addressed in the 2016 American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines.

Key Points

Question

Which systematic reviews are reliable to inform the update of the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines on cataract in the adult eye?

Findings

In a cross-sectional study, 99 systematic reviews on cataract in the adult eye were identified, and 46 (46%) were classified as reliable using prespecified criteria. All 46 reliable reviews were cited in the 2016 update of the Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines.

Meaning

The partnership between Cochrane Eyes and Vision US Satellite and the American Academy of Ophthalmology facilitated access to reliable systematic review evidence to support the development of clinical practice guidelines for cataract in the adult eye.

Abstract

Importance

Trustworthy clinical practice guidelines require reliable systematic reviews of the evidence to support recommendations. Since 2016, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) has partnered with Cochrane Eyes and Vision US Satellite to update their guidelines, the Preferred Practice Patterns (PPP).

Objective

To describe experiences and findings related to identifying reliable systematic reviews that support topics likely to be addressed in the 2016 update of the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines on cataract in the adult eye.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Cross-sectional study. Systematic reviews on the management of cataract were searched for in an established database. Each relevant systematic review was mapped to 1 or more of the 24 management categories listed under the Management section of the table of contents of the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines. Data were extracted to determine the reliability of each systematic review using prespecified criteria, and the reliable systematic reviews were examined to find whether they were referenced in the 2016 AAO PPP guidelines. For comparison, we assessed whether the reliable systematic reviews published before February 2010 the last search date of the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines were referenced in the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines. Cochrane Eyes and Vision US Satellite did not provide systematic reviews to the AAO during the development of the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Systematic review reliability was defined by reporting eligibility criteria, performing a comprehensive literature search, assessing methodologic quality of included studies, using appropriate methods for meta-analysis, and basing conclusions on review findings.

Results

From 99 systematic reviews on management of cataract, 46 (46%) were classified as reliable. No evidence that a comprehensive search had been conducted was the most common reason a review was classified as unreliable. All 46 reliable systematic reviews were cited in the 2016 AAO PPP guidelines, and 8 of 15 available reliable reviews (53%) were cited in the 2011 PPP guidelines.

Conclusions and Relevance

The partnership between Cochrane Eyes and Vision US Satellite and the AAO provides the AAO access to an evidence base of relevant and reliable systematic reviews, thereby supporting robust and efficient clinical practice guidelines development to improve the quality of eye care.

Introduction

To decide among treatment options, health care professionals benefit from consistent guidance provided in clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).1 The Institute of Medicine standards for developing trustworthy CPGs recommend using evidence from high-quality systematic reviews to inform guideline recommendations.1 Guideline developers can perform systematic reviews themselves, or they can partner with groups specializing in evidence synthesis.1

The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) partners with the Cochrane Eyes and Vision US Satellite (CEV@US) to update the Preferred Practice Pattern (PPP) guidelines.2 The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Editorial Base is located at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in London, England. Activities based in the United States are coordinated by the CEV@US at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland. The National Eye Institute has supported CEV@US since 2002. Cochrane Eyes and Vision aims to prepare and promote access to systematic reviews of interventions for preventing or treating eye conditions and/or visual impairment and helping people adjust to visual impairment or blindness.

Cochrane Eyes and Vision US Satellite was tasked to identify up-to-date, reliable systematic reviews that can be used to inform the updates to the AAO PPP guidelines. In this article, we describe our experiences and findings related to identifying reliable systematic reviews that support topics of interest that were likely to be addressed in the 2016 update of the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines on cataract in the adult eye. The PPP guidelines for cataract in the adult eye were the first collaboration of this type between the AAO and CEV@US.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

We included full-text journal articles and reports that claimed to be systematic reviews or meta-analyses anywhere in the text. We also included reports that met the definition of a systematic review or a meta-analysis when these terms were not used, as defined by the Institute of Medicine.3 For the 2016 AAO PPP guidelines for cataract in the adult eye, a systematic review was selected and evaluated when it addressed interventions for treating cataract and could be mapped to 1 of the 24 management categories covered in the Management section of the table of contents of the previous version of the guidelines, the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines for cataract in the adult eye (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The Management section was broadly divided into Nonsurgical Management and Surgical Management.

Search

Cochrane Eyes and Vision US Satellite maintains a database of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in vision research and eye care in EndNote (Clarivate Analytics). The initial search for systematic reviews was conducted in March 2007; the search was updated in September 2009, April 2012, May 2014, and March 2016 (full search strategy available in eMethods in the Supplement).4,5 For systematic reviews retrieved up to the 2012 search, 2 people independently identified eligible cataract reviews from the search results. For systematic reviews retrieved in 2014 and 2016 searches, 1 person (Y.C. in 2014 and A.G. in 2016) identified eligible cataract reviews; eligibility was verified by a senior member of the team (B.S.H.). Differences of opinion were resolved through discussion or by a third team member when necessary.

Mapping Systematic Reviews to the Management Categories

We mapped each relevant systematic review to 1 or more management categories listed in the Management section of the table of contents of the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines. A systematic review could be mapped to multiple categories. One person (A.G.) initially mapped all reviews; a senior member of the team (B.S.H.) verified the mapping. Differences of opinion were resolved through discussion.

Data Extraction and Assessment of Reliability of Systematic Reviews

We adapted a data extraction form from one used by our team in previous studies.6,7,8 Data items on the forms came from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme,9 the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews,10 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.11 We pilot-tested the form and maintained the form for data entry in the Systematic Review Data Repository.12,13 Data extracted from each review included the characteristics of the systematic review (eg, the objectives, study population, interventions compared, outcomes examined, number of studies included, key findings). We also recorded the methods used for systematic reviews, including the search strategy, the number of people involved in various steps of the systematic review process, whether risk of bias in the studies included in the review had been assessed, and how meta-analysis was conducted. Pairs of individuals (A.G., Y.C., K.L., B.R., B.S.H., T.L., and other nonauthor researchers) independently extracted data from eligible reviews and resolved discrepancies through discussion.

By comparing the extracted data with published criteria,3,14,15 we classified a systematic review method as reliable when the authors of the systematic review had (1) reported eligibility criteria for including studies, (2) conducted a comprehensive literature search for eligible studies, (3) assessed risk of bias of included studies, (4) used appropriate methods for meta-analyses if meta-analysis was reported, and (5) drawn conclusions that were supported by the review findings. Definitions of the reliability assessment criteria are given in Table 1.8,9,14,16 We considered a systematic review unreliable when 1 or more of these criteria were not met. Our classifications were based on the methods reported in the review; we did not contact review authors to obtain additional information regarding our assessment criteria.

Table 1. Criteria for Assessing the Reliability of Systematic Reviews9.

| Criterion | Definition |

|---|---|

| Defined eligibility criteria | Inclusion and/or exclusion criteria for eligible studies were described in the review. |

| Comprehensive literature search | Electronic search of more than 2 bibliographic databases that was not limited to English language. At least 1 other method of searching, such as hand searching of conference abstracts, identifying ongoing trials, contacting authors or experts, and screening reference lists, should complement the search.14 |

| Assessment of risk of bias of included studies | Use of any of the different available methods, including scales, checklists, and domain-based evaluations, for assessing methodologic rigor of studies.14 |

| Appropriate methods for meta-analysis | Statistical methods that would ensure the randomized nature of the trial and the variance estimates were used correctly for weighting the individual effect estimates.14,16 |

| Concordance between review findings and conclusions | Conclusions of the review were consistent with valid findings, provided a balanced consideration of benefits and harms, and did not favor a specific intervention despite lack of evidence.8 |

Analysis

We tabulated the characteristics and our reliability classification of the eligible reviews. We compared review characteristics and the reliability assessment for systematic reviews published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Cochrane reviews) with those of systematic reviews published elsewhere (non-Cochrane reviews).

Inclusion of Reliable Systematic Reviews in the Guidelines

We sent citations for all reliable systematic reviews, mapped to the Management section of the table of contents of the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines, along with characteristics of the reliable reviews to the AAO PPP cataract panel in February 2016 and an updated list in June 2016. After publication of the 2016 AAO PPP guidelines in October 2016,2 we examined whether the reliable systematic reviews we contributed were referenced in the 2016 AAO PPP guidelines. For comparison, we assessed whether the reliable systematic reviews published before February 2010, the last search date of the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines, had been referenced in the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines, which were developed without the same degree of CEV@US participation.

Results

Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews

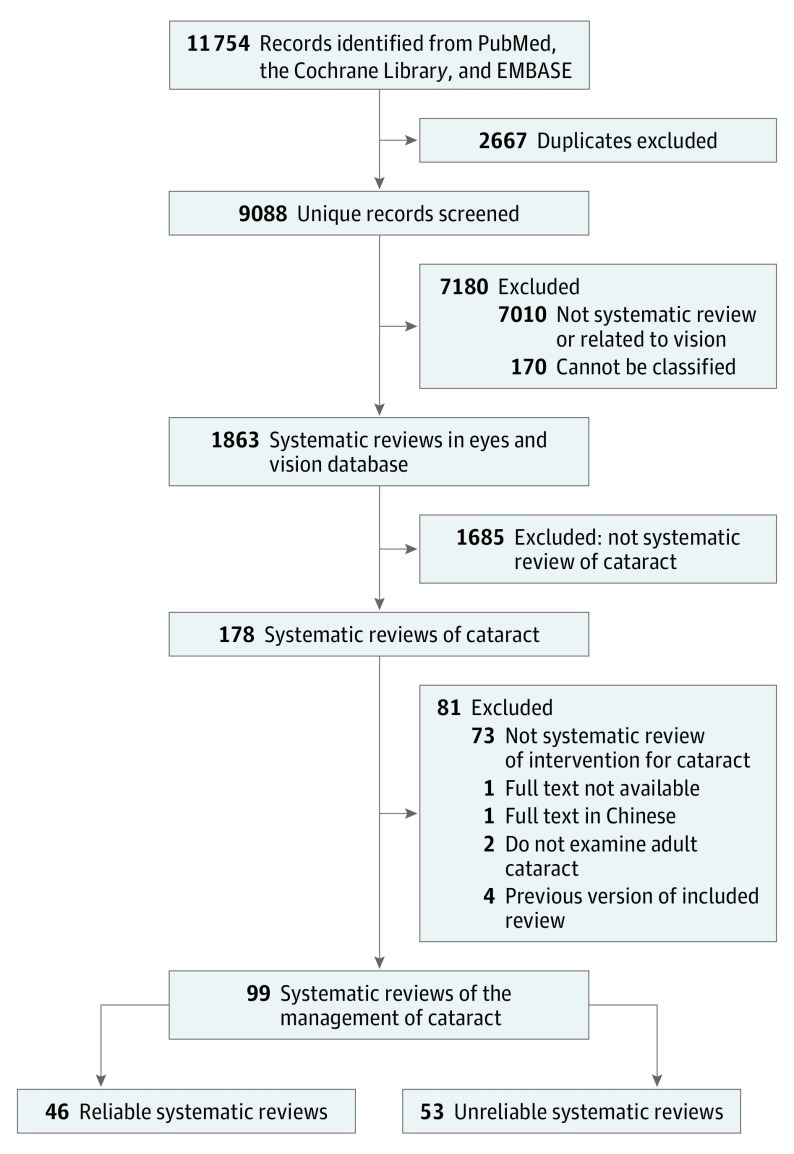

Of 1863 systematic reviews on eyes and vision in our database as of March 2016, we identified 99 that evaluated management strategies for cataract in the adult eye and were eligible for this project (Figure 1).17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115 The earliest review was published in 1994, but more than half were published after 2012 (Table 2). Twenty of 99 reviews (20%) were published by CEV authors in The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.20,22,27,30,39,41,44,45,50,52,60,64,67,75,80,87,88,93,98,111 Of the 79 non-Cochrane reviews,17,18,19,21,23,24,25,26,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,42,43,46,47,48,49,51,54,55,56,57,58,59,61,62,63,65,66,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,76,77,78,79,81,82,83,84,85,86,89,90,91,92,94,95,96,97,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,112,113,114,115 50 (63%) were published in specialty medical journals (eg, Ophthalmology). Intraocular lenses (IOL) implantation was the most commonly examined intervention (25 of 99 [25%]), followed by phacoemulsification (20 of 99 [20%]). In terms of outcomes, 59 of 99 reviews (60%) assessed visual acuity and 53 (54%) examined safety (Table 2).

Figure 1. Identification of Cataract Systematic Reviews of the Management of Cataract in the Adult Eye.

Table 2. Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews.

| Characteristics | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All Systematic Reviews (N = 99) | Reliable (n = 46) | Unreliable (n = 53) | |

| Year(s) published, median (range) | 2012 (1994-2016) | 2013 (1998-2015) | 2012 (1994- 2016) |

| Eligibility Criteria | |||

| Participantsa | |||

| Cataract (age-related cataract) | 94 (95) | 42 (91) | 52 (98) |

| Coexisting cataract and glaucoma | 7 (7) | 6 (13) | 1 (2) |

| Other (presbyopic, pediatric, astigmatic cataract) | 3 (3) | 0 | 3 (6) |

| Types of intervention examineda | |||

| Intracapsular cataract extraction | 3 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Extracapsular cataract extraction | 10 (10) | 7 (15) | 3 (6) |

| Phacoemulsification | 20 (20) | 11 (24) | 9 (17) |

| Manual small incision cataract surgery | 11 (11) | 6 (13) | 5 (9) |

| Intraocular lens implantation | 25 (25) | 12 (26) | 13 (25) |

| Anesthesia | 7 (7) | 5 (11) | 2 (4) |

| Combined cataract and glaucoma surgery | 3 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Nutritional supplement | 6 (6) | 4 (9) | 2 (4) |

| Anti-inflammatory agents | 7 (7) | 2 (4) | 5 (9) |

| Second eye cataract surgery | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Preoperative testing | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Prophylactic intervention to prevent postoperative infection | 6 (6) | 3 (7) | 3 (6) |

| Vitrectomy for retained lens fragments after cataract surgery | 3 (3) | 0 | 3 (6) |

| Systemic or topical antibiotics | 4 (4) | 3 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Others | 27 (27) | 12 (26) | 15 (28) |

| Types of outcomes examineda | |||

| Visual acuity | 59 (60) | 31 (67) | 28 (53) |

| Quality of life | 22 (22) | 19 (41) | 3 (6) |

| Contrast sensitivity | 15 (15) | 10 (22) | 5 (9) |

| Safety | 53 (54) | 31 (67) | 22 (42) |

| Cost | 13 (13) | 10 (22) | 3 (6) |

| Types of study designs includeda | |||

| Randomized clinical trial | 79 (80) | 43 (93) | 36 (68) |

| Quasirandomized clinical trial | 22 (22) | 9 (20) | 13 (25) |

| Observational studies | 37 (37) | 9 (20) | 28 (53) |

| Search | |||

| Databases searcheda | |||

| MEDLINE (PubMed) | 95 (96) | 46 (100) | 49 (92) |

| Cochrane Central Register | 67 (68) | 42 (91) | 25 (47) |

| Embase | 61 (62) | 38 (83) | 23 (43) |

| LILACS | 19 (19 | 18 (39) | 1 (2) |

| Other databases | 42 (42) | 15 (33) | 27 (51) |

| No. of databases searched, median (IQR) | 4 (2-5) | 4 (3-6) | 3 (1-4) |

| Reported searching for non-English language studies | 59 (60) | 35 (76) | 24 (45) |

| Searched all possible years for at least one database | 59 (60) | 39 (85) | 20 (38) |

| Other sources searcheda | |||

| Reference lists, reports that cited the study, or both | 67 (68) | 42 (91) | 25 (47) |

| Contacted experts in the field and/or study authors | 19 (19) | 15 (33) | 4 (8) |

| Searched hard-to-access or unpublished studies | 26 (26) | 15 (33) | 11 (21) |

| Searched for ongoing studies (eg, searched trial registries) | 24 (24) | 20 (43) | 4 (7) |

| Other Characteristics | |||

| Funding sourcesa | |||

| None | 9 (9) | 3 (7) | 6 (11) |

| Government | 39 (38) | 23 (50) | 16 (30) |

| Department/institution | 6 (6) | 6 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Industry | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 5 (9) |

| Foundation | 18 (18) | 8 (17) | 10 (19) |

| Other | 3 (3) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) |

| Not reported | 34 (34) | 13 (28) | 21 (40) |

| Financial relationship | |||

| Any types conflict of interest reported | 17 (17) | 8 (17) | 9 (17) |

| No conflict of interest reported by any author | 56 (57) | 28 (61) | 28 (53) |

Abbreviations: EMBASE, IQR, interquartile range; LILACS, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature.

Systematic reviews may be counted in more than 1 category, so totals may add to more than 100%.

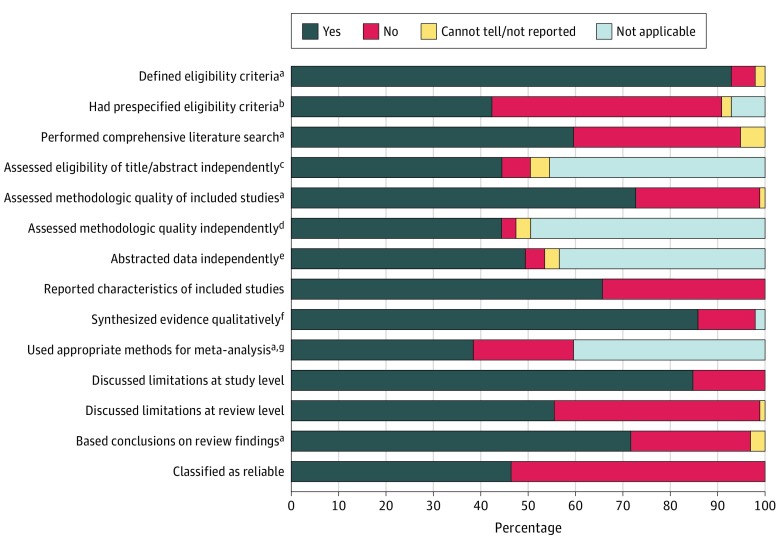

Assessment of Reliability of Included Systematic Reviews

Of the 99 systematic reviews assessed, 46 (46%) were classified as reliable, and the remaining 53 (54%) were classified as unreliable (Figure 2 and eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement). Most of the unreliable systematic reviews (43 of 53 [81%]) fell short of more than 1 reliability assessment criterion (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Lack of reporting a comprehensive search (38 of 53 [71%]) was the most frequent reason for classifying a systematic review as unreliable.

Figure 2. Assessment of Reliability of 99 Systematic Reviews on the Management of Cataract in the Adult Eye.

aFive criteria used for classifying reliability of systematic reviews.

bThe denominator was 92 for systematic reviews with defined eligibility criteria.

cThe denominator was 54 for systematic reviews reporting 2 or more title/abstract screeners.

dThe denominator was 50 for systematic reviews reporting 2 or more methodologic quality assessors.

eThe denominator was 56 for systematic reviews reporting 2 or more data abstractors.

fThe denominator was 97 for systematic reviews including at least 1 primary study.

gThe denominator was 59 for systematic reviews reporting at least 1 meta-analysis.

Characteristics of Reliable and Unreliable Systematic Reviews

Among all 99 cataract systematic reviews, the median (interquartile range) number of bibliographic databases searched per review was 4 (2-5). Almost all the authors of the systematic reviews searched PubMed (95 of 96 [96%]), and 68% (67 of 99) searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Table 2). Thirty-nine reviews (38%) reported government funding, and 18 reviews (18%) reported foundation funding. Only 5 reviews (5%) reported receiving funding from industry. The median number of studies included in these systematic reviews was 12 (interquartile range, 7-25). Fifty-eight reviews (59%) reported on the number of participants included, and 17 reviews (17%) reported on the number of eyes included. Among reviews reporting on the number of participants and eyes, the median numbers included were 1313 (interquartile range, 655-4292) and 1573 (interquartile range, 722-3800), respectively.

Compared with reliable systematic reviews, unreliable reviews less often had been developed with government funding (16 [30%] vs 23 [50%]) and more often with funding from industry (5 [9%] vs 0%) (Table 2). All 20 Cochrane reviews were classified as reliable; they accounted for 43% (n = 20) of all reliable reviews. Compared with non-Cochrane reviews, Cochrane reviews more often had 2 or more review authors who independently selected studies, assessed risk of bias, and extracted data. Neither Cochrane nor non-Cochrane reviews scored well with respect to discussing limitations of the review at the review level (eg, incomplete retrieval of relevant studies, the potential effect of reporting bias on the review findings) (eFigure in the Supplement).

Observations Regarding the Reliable Systematic Reviews

Twenty-seven of 46 reliable reviews (54%) reported that the intervention evaluated in the review was effective. Other reviews reported inconclusive findings (12 [26%]) or reported insufficient evidence of an intervention effect (7 [15%]) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). In about one-third of these 46 reviews (15 of 46 [33%]), different groups of reviewers had examined the same intervention. Among reviews investigating the same intervention, not all reported consistent findings. For example, 4 reviews compared sharp-edged IOL with round-edged IOL, and all favored sharp-edged IOLs over round-edged IOLs.24,45,68,76 As another example, in comparisons of manual small incision cataract surgery vs extracapsular cataract extraction, Ang et al22 reported inconclusive findings, but Riaz et al88 found manual small incision cataract surgery was more effective than extracapsular cataract extraction. This discordance may be due to the different visual acuity outcomes used to reach their conclusions: Ang et al22 used best-corrected visual acuity, and Riaz et al88 used uncorrected visual acuity. We provided the AAO with both reviews so that the panelists could decide whether and how the discordant findings affected their recommendations.

Inclusion of Reliable Systematic Reviews in the 2016 AAO PPP Guidelines

We sent references for the reliable systematic reviews to the AAO cataract guideline panel for use in updating the 2016 AAO PPP guidelines for cataract in the adult eye. These reviews were mapped to 18 of the 24 management categories (75%) of the table of contents of the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines. We did not identify any reliable systematic review for 6 of the 24 management categories (25%): indications for surgery, contraindications to surgery, biometry and IOL power calculation, toxic anterior segment syndrome, cataract surgery checklist, and discharge from surgical facility. There may be a need for randomized clinical trials and systematic reviews in these areas (eTable 4 in the Supplement). We identified reliable systematic reviews for 2 topics that were not covered in the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines: prophylaxis for cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery90,94,104,109 and timing for cataract surgery.38,54 All 46 reliable systematic reviews were cited in the 2016 AAO PPP guidelines. In contrast, before the close partnership between CEV@US and AAO was established, only 8 of 15 reliable systematic reviews (53%) available at that time were cited in the 2011 AAO PPP guidelines. Although CEV@US has never sent unreliable systematic reviews to the AAO PPP panel, we noticed that the 2016 AAO PPP guidelines cited 16 unreliable systematic reviews in various contexts. Two unreliable systematic reviews were used to inform treatment recommendations.51,113

Discussion

We contributed 46 reliable systematic reviews, nearly half of all 99 eligible reviews we had identified, to the guideline panel charged with preparing the 2016 update of the AAO PPP guidelines on the management of cataract in the adult eye. Most of the unreliable reviews fell short on more than 1 methodologic criterion. No evidence of a comprehensive literature search was the most common reason for classifying a review as unreliable. Cochrane reviews constituted a fifth of all identified reviews and were all classified as reliable.

Achieving evidence-based health care involves an intense effort. First, evidence must be generated, and then the available evidence must be synthesized in a reliable way. Synthesized evidence must be further translated into policy, often manifested as evidence-based CPGs. Finally, the policy must be applied for the evidence to have an effect on care. It takes a coordinated effort among stakeholders to achieve the collective needs of patients, caregivers, and policy makers. Collaboration between systematic reviewers and guideline developers is necessary to target important topics to be addressed in systematic reviews and to improve the trustworthiness and validity of CPGs,1 as evidenced by the increased reference to reliable evidence in the 2016 AAO PPP guidelines. This close collaboration facilitates active dissemination of systematic review findings. We believe our approach of working directly with guideline developers aligns well with the 5 core areas for change outlined in the 2016 National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine report Making Eye Health a Population Health Imperative: Vision for Tomorrow, specifically, generating evidence to guide policy decisions and evidence-based actions.116

As a result of this project, we identified 6 topics without a reliable published systematic review. Treatment recommendations in these management categories were made on the basis of the findings from individual studies or expert consensus. While some of the studies that supported treatment recommendations were well-designed and widely known randomized clinical trials, reliable systematic reviews of data available from all studies that have addressed the same research question offer a more comprehensive and compelling evidence base than individual studies. Furthermore, systematic reviews are particularly useful for evaluating consistency of findings across all studies of the same research question and for studying outcomes that are rare (eg, adverse events).117 Future collaborations between clinical researchers, CEV@US, and AAO could focus on important clinical questions in which there are a need for evidence generation and/or synthesis.

Our use of the word reliable refers to the reliability of the methods used by the systematic reviewers. The criteria we used to categorize reliable reviews were based on the standards set by the Institute of Medicine and the Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews.3,15 However, our criteria were more modest than these standards as we used only a few important items from the full set of recommendations for assessing the reliability of reviews.

Consistent with our previous work on glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration7,8 and work in other areas,118,119,120,121 we found that a large proportion of published systematic reviews were redundant and unreliable. This constitutes a form of research waste.122 To ensure the production of reliable systematic reviews, methodologic and reporting standards must be followed. Other considerations include ensuring that systematic reviews are conducted by individuals with adequate training, and that reports of systematic reviews are reviewed by peer reviewers and editors knowledgeable in methods and reporting standards for systematic reviews.123 Cochrane Eyes and Vision is partnering with 10 major vision science journals, whereby a CEV methodologist serves as an editor for systematic review manuscripts submitted for publication.124

We believe that reliable reviews are more likely than unreliable reviews to be reproducible and provide high-quality summarized findings from research. The Institute of Medicine recommends that CPGs be based on high-quality systematic reviews.1 These reviews may be de novo reviews conducted or contracted by the guideline developers or already existing reviews. Although developers may want to conduct a new systematic review to ensure inclusion of the most up-to-date primary research or to address the questions deemed most important for the CPG, it may not be efficient or necessary to conduct a new review given the amount of primary literature to be examined for each review. Because most CPGs address a variety of clinically distinct scenarios, it would be an enormous undertaking to conduct a new systematic review for each clinical question, an undertaking likely impossible to complete within realistic time frames. For example, the AAO cataract PPP guidelines address a diverse number of questions, including nonsurgical management, surgical management, and anesthesia for surgery.3 In such cases, it may be preferable to use reliable existing reviews to inform recommendations, as the PPP panel did, and only conduct new systematic reviews of the primary literature when there are no existing reviews or the existing review is dangerously out-of-date.

Strengths and Limitations

Our investigation had strengths. The database of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in vision research and eye care was not compiled specifically for the purpose of informing the AAO panel charged with updating the PPP guidelines for management of cataract in adult eyes or any other team of CPG developers. It was assembled, updated, and coded to cover a broad range of eye and vision conditions and to serve researchers and users with diverse interests. Coding of reviews by condition and by area of relevance to cataract management was performed independently by 2 or more members of CEV. Our investigation also has limitations. First, we limited our investigation to systematic reviews published in English and Chinese, which 1 or more of us could read. We did not translate articles written in other languages. In addition, application of our reliability criteria was subjective and may have reflected our connections to Cochrane.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the collaboration between CEV@US and AAO is a positive step toward identifying reliable systematic reviews and using them to inform guideline recommendations. The increased proportion of available and reliable systematic reviews cited by the AAO panel between the 2011 and 2016 versions of the cataract PPP guidelines demonstrated the success of this close interaction between guideline developers and systematic review groups, as emphasized by the Institute of Medicine. We look forward to continuing and expanding this partnership, to partnering with others responsible for developing CPGs and formulating policy, and to identifying areas in need of evidence generation and synthesis.

eMethods. Search strategies for identifying systematic reviews in eyes and vision research

eTable 1. 2011 Academy for Ophthalmology (AAO) Preferred Practice Patterns (PPP) Table of Content for Cataract in the Adult Eye

eTable 2. Characteristics of 46 reliable systematic reviews on the management of cataract in the adult eye

eTable 3. Characteristics of 53 unreliable systematic reviews on the management of cataract in the adult eye

eTable 4. Management categories in the 2011 PPP with evidence gaps

eFigure. Assessment of reliability of 99 systematic reviews on the management of cataract in the adult eye by Cochrane affiliation

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olson RJ, Braga-Mele R, Chen SH, et al. . Cataract in the adult eye preferred practice pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(2):P1-P119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine Finding what works in health care: standards for systematic reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li T, Ervin AM, Scherer R, Jampel H, Dickersin K. Setting priorities for comparative effectiveness research: a case study using primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(10):1937-1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Straus S, Moher D. Registering systematic reviews. CMAJ. 2010;182(1):13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu T, Li T, Lee KJ, Friedman DS, Dickersin K, Puhan MA. Setting priorities for comparative effectiveness research on management of primary angle closure: a survey of Asia-Pacific clinicians. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(5):348-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsley K, Li T, Ssemanda E, Virgili G, Dickersin K. Interventions for age-related macular degeneration: Are practice guidelines based on systematic reviews? Ophthalmology. 2016;123(4):884-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li T, Vedula SS, Scherer R, Dickersin K. What comparative effectiveness research is needed? a framework for using guidelines and systematic reviews to identify evidence gaps and research priorities. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(5):367-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative research: appraisal tool. 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Oxford, England: Public Health Resource Unit; 2006:1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. . Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264-269, W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ip S, Hadar N, Keefe S, et al. . A web-based archive of systematic review data. Syst Rev. 2012;1:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li T, Vedula SS, Hadar N, Parkin C, Lau J, Dickersin K. Innovations in data collection, management, and archiving for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):287-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration website. http://training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed March 5, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Lasserson T, Chandler J, Tovey D, Churchill R. Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews. London: Cochrane; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glenny AM, Altman DG, Song F, et al. ; International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group . Indirect comparisons of competing interventions. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(26):1-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agresta B, Knorz MC, Donatti C, Jackson D. Visual acuity improvements after implantation of toric intraocular lenses in cataract patients with astigmatism: a systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012;12:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agresta B, Knorz MC, Kohnen T, Donatti C, Jackson D. Distance and near visual acuity improvement after implantation of multifocal intraocular lenses in cataract patients with presbyopia: a systematic review. J Refract Surg. 2012;28(6):426-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akram A, Juret K, Minavar A, Wu TX. Preoperative routine testings vs selective routine testings in the safty [safety] of cataract surgery: a systematic review. Chin J Evidence-Based Med. 2009;9(4):476-480. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhassan MB, Kyari F, Ejere HO. Peribulbar versus retrobulbar anaesthesia for cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(7):CD004083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen D. Cataract. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011;2011:0708. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ang M, Evans JR, Mehta JS. Manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS) with posterior chamber intraocular lens versus extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) with posterior chamber intraocular lens for age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD008811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartlett H, Eperjesi F. Nutrition and age-related ocular disease. Curr Top Nutraceutical Res. 2005;3(4):231-242. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buehl W, Findl O. Effect of intraocular lens design on posterior capsule opacification. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(11):1976-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cataract surgery performed under local anaesthesia: guidelines. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health https://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/htis/nov-2014/RB0714%20Cataract%20Surgery%20Final.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2018.

- 26.TECNIS® or Acrysof® soft intraocular lenses for patients undergoing cataract surgery: benefits and harms, clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and guidelines Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health https://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/htis/feb-2014/RB0639%20Lenses%20for%20Cataract%20Surgery%20Final.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2018.

- 27.Calladine D, Evans JR, Shah S, Leyland M. Multifocal versus monofocal intraocular lenses after cataract extraction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9(9):CD003169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao H, Zhang L, Li L, Lo S. Risk factors for acute endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carter MJ, Limburg H, Lansingh VC, Silva JC, Resnikoff S. Do gender inequities exist in cataract surgical coverage? meta-analysis in Latin America. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;40(5):458-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casparis H, Lindsley K, Kuo IC, Sikder S, Bressler NB. Surgery for cataracts in people with age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(6):CD006757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chatziralli IP, Sergentanis TN. Risk factors for intraoperative floppy iris syndrome: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(4):730-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen C, Zhu M, Sun Y, Qu X, Xu X. Bimanual microincision versus standard coaxial small-incision cataract surgery: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2015;25(2):119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng J-W, Wei R-L, Cai J-P, et al. . Efficacy of different intraocular lens materials and optic edge designs in preventing posterior capsular opacification: a meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(3):428-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chou R, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Grusing S, Blazina I. Screening for impaired visual acuity in older adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(9):915-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciulla TA, Starr MB, Masket S. Bacterial endophthalmitis prophylaxis for cataract surgery: an evidence-based update. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(1):13-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cochener B, Lafuma A, Khoshnood B, Courouve L, Berdeaux G. Comparison of outcomes with multifocal intraocular lenses: a meta-analysis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:45-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conner-Spady B, Sanmartin C, Sanmugasunderam S, et al. . A systematic literature review of the evidence on benchmarks for cataract surgery waiting time. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42(4):543-551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cui YH, Jing CX, Pan HW. Association of blood antioxidants and vitamins with risk of age-related cataract: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(3):778-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Silva SR, Riaz Y, Evans JR. Phacoemulsification with posterior chamber intraocular lens versus extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) with posterior chamber intraocular lens for age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD008812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Desapriya E, Subzwari S, Scime-Beltrano G, Samayawardhena LA, Pike I. Vision improvement and reduction in falls after expedited cataract surgery Systematic review and metaanalysis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36(1):13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Do DV, Gichuhi S, Vedula SS, Hawkins BS. Surgery for post-vitrectomy cataract. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):CD006366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dowler JG, Hykin PG, Lightman SL, Hamilton AM. Visual acuity following extracapsular cataract extraction in diabetes: a meta-analysis. Eye (Lond). 1995;9(Pt 3):313-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunfield L, Boudreau R, Nkansah E. Sharp and Round Optic Edges of Intraocular Lenses: a Review of the Clinical and Cost-Effectiveness. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ezra DG, Allan BD. Topical anaesthesia alone versus topical anaesthesia with intracameral lidocaine for phacoemulsification. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD005276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Findl O, Buehl W, Bauer P, Sycha T. Interventions for preventing posterior capsule opacification. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(2):CD003738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frampton G, Harris P, Cooper K, Lotery A, Shepherd J. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of second-eye cataract surgery: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(68):1-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedman DS, Bass EB, Lubomski LH, et al. . Synthesis of the literature on the effectiveness of regional anesthesia for cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(3):519-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman DS, Jampel HD, Lubomski LH, et al. . Surgical strategies for coexisting glaucoma and cataract: an evidence-based update. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(10):1902-1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gogate P, Optom JJ, Deshpande S, Naidoo K. Meta-analysis to compare the safety and efficacy of manual small incision cataract surgery and phacoemulsification. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22(3):362-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gower EW, Lindsley K, Nanji AA, Leyngold I, McDonnell PJ. Perioperative antibiotics for prevention of acute endophthalmitis after cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(7):CD006364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grzybowski A, Ascaso FJ, Kupidura-Majewski K, Packer M. Continuation of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy during phacoemulsification cataract surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(1):28-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guay J, Sales K. Sub-Tenon’s anaesthesia versus topical anaesthesia for cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(8):CD006291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hodge W, Horsley T, Albiani D, et al. . The consequences of waiting for cataract surgery: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2007;176(9):1285-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hodge W, Barnes D, Schachter HM, et al. . Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on eye health. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2005;(117):1-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ishikawa T, Desapriya E, Puri M, Kerr JM, Hewapathirane DS, Pike I. Evaluating the benefits of second-eye cataract surgery among the elderly. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39(10):1593-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jaggernath J, Gogate P, Moodley V, Naidoo KS. Comparison of cataract surgery techniques: safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2014;24(4):520-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jampel HD, Friedman DS, Lubomski LH, et al. . Effect of technique on intraocular pressure after combined cataract and glaucoma surgery: an evidence-based review. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(12):2215-2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jamula E, Anderson J, Douketis JD. Safety of continuing warfarin therapy during cataract surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2009;124(3):292-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jinwei C, Xiaoping Y, Ruili W, Jiping C, You L. Effect of heparin-surface-modified intraocular lenses on posterior capsular opacification: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trial. Chin Ophthalmic Res. 2008;26(6):462-465. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keay L, Lindsley K, Tielsch J, Katz J, Schein O. Routine preoperative medical testing for cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3(3):CD007293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kessel L, Flesner P, Andresen J, Erngaard D, Tendal B, Hjortdal J. Antibiotic prevention of postcataract endophthalmitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(4):303-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kessel L, Tendal B, Jørgensen KJ, et al. . Post-cataract prevention of inflammation and macular edema by steroid and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory eye drops: a systematic review. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(10):1915-1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kostis JB, Dobrzynski JM. Prevention of cataracts by statins: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19(2):191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lawrence D, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ. Day care versus in-patient surgery for age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(11):CD004242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leibovici D, Bar-Kana Y, Zadok D, Lindner A. Association between tamsulosin and intraoperative “floppy-iris” syndrome. Isr Med Assoc J. 2009;11(1):45-49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lesin M, Domazet Bugarin J, Puljak L. Factors associated with postoperative pain and analgesic consumption in ophthalmic surgery: a systematic review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2015;60(3):196-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leung TG, Lindsley K, Kuo IC. Types of intraocular lenses for cataract surgery in eyes with uveitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD007284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li N, Chen X, Zhang J, et al. . Effect of AcrySof versus silicone or polymethyl methacrylate intraocular lens on posterior capsule opacification. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(5):830-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Linertová R, Abreu-González R, García-Pérez L, et al. . Intracameral cefuroxime and moxifloxacin used as endophthalmitis prophylaxis after cataract surgery: systematic review of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1515-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu HN, Chen XL, Li X, Nie QZ, Zhu Y. Efficacy and tolerability of one-site versus two-site phaco-trabeculectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123(15):2111-2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu J, Jones RE, Zhao J, Zhang J, Zhang F. Influence of uncomplicated phacoemulsification on central macular thickness in diabetic patients: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu J, Zhao J, Ma L, Liu G, Wu D, Zhang J. Contrast sensitivity and spherical aberration in eyes implanted with AcrySof IQ and AcrySof Natural intraocular lens: the results of a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu JP, Zhang F, Zhao JY, Ma LW, Zhang JS. Visual function and higher order aberration after implantation of aspheric and spherical multifocal intraocular lenses: a meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013;6(5):690-695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu YB, Tan SJ, Chen YY. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing aspheric intraocular lenses with spherical intraocular lenses in the treatment of cataract surgery. Chin J Evidence-Based Med. 2009;9(9):1001-1009. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mathew MC, Ervin A-M, Tao J, Davis RM. Antioxidant vitamin supplementation for preventing and slowing the progression of age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(6):CD004567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Health Quality Ontario Intraocular lenses for the treatment of age-related cataracts: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2009;9(15):1-62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mehta S, Linton MM, Kempen JH. Outcomes of cataract surgery in patients with uveitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(4):676-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Migliore A, Corio M, Paone S, Cerbo M, Jefferson T. Accommodating Intraocular Lenses for Patients With Cataract. Rome, Italy: National Agency for Regional Healthcare; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mousavi S, Moradi M, Khorshidahmad T, Motamedi M. Anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and its derivatives: a systematic review. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2015;2015:507151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ong HS, Evans JR, Allan BD. Accommodative intraocular lens versus standard monofocal intraocular lens implantation in cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(5):CD009667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pathengay A, Flynn HW Jr, Isom RF, Miller D. Endophthalmitis outbreaks following cataract surgery: causative organisms, etiologies, and visual acuity outcomes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(7):1278-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pirouzian A, Craven ER. Critical appraisal of loteprednol ointment, gel, and suspension in the treatment of postoperative inflammation and pain following ocular and corneal transplant surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:379-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pleyer U, Ursell PG, Rama P. Intraocular pressure effects of common topical steroids for post-cataract inflammation: are they all the same? Ophthalmol Ther. 2013;2(2):55-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Porela-Tiihonen S, Kaarniranta K, Kokki H. Postoperative pain after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39(5):789-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Powe NR, Schein OD, Gieser SC, et al. ; Cataract Patient Outcome Research Team . Synthesis of the literature on visual acuity and complications following cataract extraction with intraocular lens implantation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112(2):239-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Quinones A, Gleitsmann K, Freeman M, et al. . Benefits and Harms of Femtosecond Laser Assisted Cataract Surgery: a Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Riaz Y, de Silva SR, Evans JR. Manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS) with posterior chamber intraocular lens versus phacoemulsification with posterior chamber intraocular lens for age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD008813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Riaz Y, Mehta JS, Wormald R, et al. . Surgical interventions for age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD001323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rossetti L, Chaudhuri J, Dickersin K. Medical prophylaxis and treatment of cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery: the results of a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(3):397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schaumberg DA, Dana MR, Christen WG, Glynn RJ. A systematic overview of the incidence of posterior capsule opacification. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(7):1213-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schuster AK, Tesarz J, Vossmerbaeumer U. The impact on vision of aspheric to spherical monofocal intraocular lenses in cataract surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(11):2166-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sheng Y, Sun W, Gu Y, Lou J, Liu W. Endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in China, 1995-2009. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(9):1715-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sivaprasad S, Bunce C, Crosby-Nwaobi R. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents for treating cystoid macular oedema following cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2(2):CD004239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Song E, Sun H, Xu Y, Ma Y, Zhu H, Pan CW. Age-related cataract, cataract surgery and subsequent mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Subzwari S, Desapriya E, Scime G, Babul S, Jivani K, Pike I. Effectiveness of cataract surgery in reducing driving-related difficulties: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inj Prev. 2008;14(5):324-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Taban M, Behrens A, Newcomb RL, et al. . Acute endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(5):613-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Takakura A, Iyer P, Adams JR, Pepin SM. Functional assessment of accommodating intraocular lenses versus monofocal intraocular lenses in cataract surgery: meta-analysis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36(3):380-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thomas RE, Crichton A, Thomas BC. Antimetabolites in cataract surgery to prevent failure of a previous trabeculectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD010627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Van den Bruel A, Gailly J, Devriese S, Welton NJ, Shortt AJ, Vrijens F. The protective effect of ophthalmic viscoelastic devices on endothelial cell loss during cataract surgery: a meta-analysis using mixed treatment comparisons. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(1):5-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vanner EA, Stewart MW. Vitrectomy timing for retained lens fragments after surgery for age-related cataracts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(3):345-357.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vanner EA, Stewart MW. Meta-analysis comparing same-day versus delayed vitrectomy clinical outcomes for intravitreal retained lens fragments after age-related cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:2261-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wagoner MD, Cox TA, Ariyasu RG, Jacobs DS, Karp CL; American Academy of Ophthalmology . Intraocular lens implantation in the absence of capsular support: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(4):840-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wielders LH, Lambermont VA, Schouten JS, et al. . Prevention of cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery in nondiabetic and diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(5):968-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wilson DJ, Schutte SM, Abel SR. Comparing the efficacy of ophthalmic NSAIDs in common indications: a literature review to support cost-effective prescribing. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(6):727-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xu J. System evaluation of curative effects of intraocular lens implantation for treating diabetic cataract. J Clin Rehab Tissue Eng Res. 2009;13(25):4969-4972. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Xu X, Zhu MM, Zou HD. Refractive versus diffractive multifocal intraocular lenses in cataract surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Refract Surg. 2014;30(9):634-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yang CJ, Zeng LT, Jiang M. Curative effects of small incision cataract surgery vs phacoemulsification: a meta-analysis. Int Eye Sci. 2013;(4):1550-1554. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yilmaz T, Cordero-Coma M, Gallagher MJ. Ketorolac therapy for the prevention of acute pseudophakic cystoid macular edema: a systematic review. Eye (Lond). 2012;26(2):252-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yu JG, Zhao YE, Shi JL, et al. . Biaxial microincision cataract surgery versus conventional coaxial cataract surgery: metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(5):894-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang JY, Feng YF, Cai JQ. Phacoemulsification versus manual small-incision cataract surgery for age-related cataract: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41(4):379-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang ML, Hirunyachote P, Jampel H. Combined surgery versus cataract surgery alone for eyes with cataract and glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(7):CD008671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhao LQ, Li LM, Zhu H; The Epidemiological Evidence-Based Eye Disease Study Research Group EY The effect of multivitamin/mineral supplements on age-related cataracts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2014;6(3):931-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhao LQ, Zhu H, Zhao PQ, Wu QR, Hu YQ. Topical anesthesia versus regional anesthesia for cataract surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(4):659-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhu MM, Yu YF, Zou HD. Meta-analysis on changes of tear film and tear secretion after phacoemulsification for cataract. Int J Ophthalmol. 2010;10(8):1513-1515. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhu XF, Zou HD, Yu YF, Sun Q, Zhao NQ. Comparison of blue light-filtering IOLs and UV light-filtering IOLs for cataract surgery: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Making Eye Health a Population Health Imperative: Vision for Tomorrow. Washington, DC: The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine;2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Etminan M, Carleton B, Rochon PA. Quantifying adverse drug events : are systematic reviews the answer? Drug Saf. 2004;27(11):757-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.MacDonald SL, Canfield SE, Fesperman SF, Dahm P. Assessment of the methodological quality of systematic reviews published in the urological literature from 1998 to 2008. J Urol. 2010;184(2):648-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Melchiors AC, Correr CJ, Venson R, Pontarolo R. An analysis of quality of systematic reviews on pharmacist health interventions. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(1):32-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Seo HJ, Kim KU. Quality assessment of systematic reviews or meta-analyses of nursing interventions conducted by Korean reviewers. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Aziz T, Compton S, Nassar U, Matthews D, Ansari K, Flores-Mir C. Methodological quality and descriptive characteristics of prosthodontic-related systematic reviews. J Oral Rehabil. 2013;40(4):263-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ioannidis JP, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, et al. . Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):166-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Li T, Bartley GB. Publishing systematic reviews in ophthalmology: new guidance for authors. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(2):438-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Associate editors at eyes and visions journals. Cochrane Eyes and Vision website. http://eyes.cochrane.org/associate-editors-eyes-and-vision-journals. Accessed March 7, 2018.

- 125.Finding What Works IOM. Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Search strategies for identifying systematic reviews in eyes and vision research

eTable 1. 2011 Academy for Ophthalmology (AAO) Preferred Practice Patterns (PPP) Table of Content for Cataract in the Adult Eye

eTable 2. Characteristics of 46 reliable systematic reviews on the management of cataract in the adult eye

eTable 3. Characteristics of 53 unreliable systematic reviews on the management of cataract in the adult eye

eTable 4. Management categories in the 2011 PPP with evidence gaps

eFigure. Assessment of reliability of 99 systematic reviews on the management of cataract in the adult eye by Cochrane affiliation