Key Points

Question

Does a patient-specific preconversation communication-priming intervention (Jumpstart-Tips), which targets both patients with serious illness and clinicians, increase goals-of-care conversations compared with usual care?

Findings

In this multicenter cluster-randomized trial of 132 clinicians and 537 patients, the Jumpstart-Tips intervention resulted in a significant increase in patient-reported goals-of-care conversations during routine outpatient clinic visits, from 31% in the usual care group compared with 74% in the intervention group. The intervention also increased the patient-reported quality of these discussions.

Meaning

An intervention that primes patients with serious illness and outpatient clinicians might be considered in the clinical setting to increase goals-of-care conversations.

Abstract

Importance

Clinician communication about goals of care is associated with improved patient outcomes and reduced intensity of end-of-life care, but it is unclear whether interventions can improve this communication.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of a patient-specific preconversation communication-priming intervention (Jumpstart-Tips) targeting both patients and clinicians and designed to increase goals-of-care conversations compared with usual care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Multicenter cluster-randomized trial in outpatient clinics with physicians or nurse practitioners and patients with serious illness. The study was conducted between 2012 and 2016.

Interventions

Clinicians were randomized to the bilateral, preconversation, communication-priming intervention (n = 65) or usual care (n = 67), with 249 patients assigned to the intervention and 288 to usual care.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was patient-reported occurrence of a goals-of-care conversation during a target outpatient visit. Secondary outcomes included clinician documentation of a goals-of-care conversation in the medical record and patient-reported quality of communication (Quality of Communication questionnaire [QOC]; 4-indicator latent construct) at 2 weeks, as well as patient assessments of goal-concordant care at 3 months and patient-reported symptoms of depression (8-item Patient Health Questionnaire; PHQ-8) and anxiety (7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder survey; GAD-7) at 3 and 6 months. Analyses were clustered by clinician and adjusted for confounders.

Results

We enrolled 132 of 485 potentially eligible clinicians (27% participation; 71 women [53.8%]; mean [SD] age, 47.1 [9.6] years) and 537 of 917 eligible patients (59% participation; 256 women [47.7%]; mean [SD] age, 73.4 [12.7] years). The intervention was associated with a significant increase in a goals-of-care discussion at the target visit (74% vs 31%; P < .001) and increased medical record documentation (62% vs 17%; P < .001), as well as increased patient-rated quality of communication (4.6 vs 2.1; P = .01). Patient-assessed goal-concordant care did not increase significantly overall (70% vs 57%; P = .08) but did increase for patients with stable goals between 3-month follow-up and last prior assessment (73% vs 57%; P = .03). Symptoms of depression or anxiety were not different between groups at 3 or 6 months.

Conclusions and Relevance

This intervention increased the occurrence, documentation, and quality of goals-of-care communication during routine outpatient visits and increased goal-concordant care at 3 months among patients with stable goals, with no change in symptoms of anxiety or depression. Understanding the effect on subsequent health care delivery will require additional study.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01933789

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the effect of a communication-priming intervention designed to increase patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians vs usual care.

Introduction

Physicians caring for patients with serious illness frequently do not talk with patients about their prognosis or goals of care, and yet, when this communication occurs, it is associated with increased quality of life, increased quality of dying, and reduced intensity of care at the end of life.1,2,3,4 In focus groups of patients and families, quality of communication is a key domain of clinician skill in palliative care, mentioned more frequently than any other domain.5 Physicians seem to be unaware of their failure to meet patients’ communication needs, reporting high satisfaction with their own communication that contrasts with patients’ evaluations.6,7 Although the availability of palliative care specialists in hospitals has increased, access to these specialists in the outpatient setting is limited. New approaches are needed that will increase the occurrence and quality of goals-of-care communication between clinicians and outpatients with serious illness.8,9,10

Over the past 3 decades, negative findings in studies designed to increase goals-of-care communication with patients with serious illness raised concerns that such communication could not be improved.11,12,13 However, a randomized clinical trial targeting hospitalized patients older than 80 years showed that advance care planning by a trained specialist was associated with improved quality of life, reduced intensity of care at the end of life, and reduced psychological distress among family.14 Many patients report that they want to discuss their goals of care when they are feeling well enough to participate5,15 and that they want this communication with the physicians caring for them as opposed to with a different advance care planning specialist.16,17 The challenge has been to develop a scalable intervention that increases and improves goals-of-care communication for patients with serious illness in outpatient settings.

In prior work, our research team developed an intervention that used information obtained from patients with serious illness about their preferences for goals-of-care communication and their patient-specific barriers and facilitators to this communication.18 The intervention used this information to prime and support goals-of-care communication between patients and clinicians. It was tested among patients with moderate or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the Veterans Affairs system, demonstrating an increase in the proportion of patients reporting goals-of-care conversations from 11% to 30% and a moderate increase in the patient-reported quality of this communication (Cohen effect size, 0.26).18

In the present report, we describe the results of the next generation of this bilateral, patient-specific communication-priming intervention. We generated patient-specific tips for patients and clinicians, provided a brief video instructing clinicians and patients on use of the form, and expanded the study population to patients with many types of chronic, life-limiting illnesses. We hypothesized that the intervention would increase the proportion of patients reporting a goals-of-care discussion with the clinician, clinicians’ documentation of these discussions in the electronic health record (EHR), and patient-reported quality of communication. In addition, we examined the effect on patient-reported goal-concordant care at 3 months and patient-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression at 3 and 6 months.

Methods

We conducted a cluster-randomized trial assigning clinicians to intervention or enhanced usual care—enhanced in that it included completion of baseline surveys and regular contact with study personnel to increase study retention. Institutional review boards at all sites approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol and other forms are available in Supplement 1.

Participants and Eligibility Criteria

Clinicians

Clinicians were recruited from 2 large health care systems in the Pacific Northwest. One includes 2 academic and 2 community hospitals, a comprehensive cancer center, and an extensive outpatient network; the other includes 3 community hospitals and an extensive outpatient network. Eligible clinicians included physicians and nurse practitioners providing primary or specialty care. Clinicians, who were eligible if they had 5 or more eligible patients in their panels, were approached by mail or email, with telephone or in-person follow-up.

Patients

Using the EHR and clinic schedules, study staff identified consecutive patients cared for by participating clinicians with the following eligibility criteria: age 18 years or older, 2 or more visits with the clinician in the last 18 months, and 1 or more of the qualifying conditions. Qualifying conditions included (1) metastatic cancer or inoperable lung cancer; (2) COPD with forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) values below 35% of that predicted or oxygen dependence, restrictive lung disease with a total lung capacity below 50% of that predicted, or cystic fibrosis with FEV1 below 30% of that predicted; (3) New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure, pulmonary arterial hypertension with a 6-minute walk distance less than 250 m, or left ventricular assist device or implantable cardioverter defibrillator implant; (4) Child’s class C cirrhosis or Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score greater than 17; (5) dialysis-dependent renal failure and diabetes; (6) age 75 years or older and 1 or more life-limiting chronic illnesses; (7) age 90 years or older; (8) hospitalization in the past 18 months with a life-limiting illness; or (9) a Charlson comorbidity score of 6 or higher. The qualifying criteria were selected to identify a median survival of approximately 2 years, suggesting relevance of goals-of-care discussions.19,20,21,22,23 Study staff contacted eligible patients by mail or telephone.

Interventions

Jumpstart-Tips Intervention

Patients in the intervention arm received a survey designed to identify their individual preferences, barriers, and facilitators for communication about end-of-life care (see the survey in Supplement 2).24,25,26 Surveys could be self-administered or completed with assistance. Based on each patient’s responses to survey items, we used an algorithm to (1) create an abstracted version of the patient’s preferences; (2) identify the most important communication barrier or facilitator; and (3) provide communication tips based on VitalTalk curricular material (http://vitaltalk.org/) tailored to patient responses (see the algorithm in Supplement 2). For example, if a patient indicated that they were reluctant to discuss end-of-life care, clinicians received this information along with a tip to enable clinicians to work around reluctance.27,28 The 1-page Jumpstart-Tips was sent to clinicians by email or fax 1 or 2 working days prior to the patient’s target clinic visit (Supplement 2). One week prior to the clinic visit, patients also received patient-specific 1-page Jumpstart-Tips forms, which summarized their survey responses and provided suggestions for having a goals-of-care conversation with the clinician (Supplement 2). The goal of this intervention was to prime clinicians and patients for a brief discussion of goals of care during a routine clinic visit. An estimate of the resources required to field this intervention is provided in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Control Intervention

Patients randomized to the control group completed the same surveys, but no information from the surveys was provided to patients or clinicians.

Outcomes

Primary Outcome—Occurrence of Goals-of-Care Communication

Patient-reported occurrence of communication was evaluated using a previously validated dichotomous survey item.4,18

EHR Documentation of Goals-of-Care Discussion

Study staff blinded to study arm reviewed all patients’ EHRs to identify documentation from the target visit through the following 6 months regarding goals-of-care discussions, advance care planning, and discussions about palliative or hospice care, which were coded as absent or present; there was no specific note template for this content in the EHR. We conducted blinded coreviews for 10% of medical records and found 95% agreement for all abstracted elements.

Quality of Communication

The Quality of Communication questionnaire (QOC) is a 17-item survey developed from qualitative studies with patients, families, and clinicians,4,15,29 in which 13 items were identified as measuring 2 components: general communication (6 items) and communication about end-of-life care (7 items).29 We administered only the end-of-life items and, from these, selected a priori 4 items that were directly targeted by this intervention. Each item measures the clinician’s skill at a specific aspect of communication and is either rated on a scale from 0 (“very worst I can imagine”) to 10 (“very best I can imagine”), or identified as something the clinician did not do. For analysis, the 0 to 10 ratings were recoded to 1 to 11, with 0 imputed for “did not do.” We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the 4 selected items for unidimensionality and scalar measurement invariance between groups (intervention and control) and over 2 assessments (baseline and 2 weeks). The items were defined as censored from below (due to high frequencies of “did not do”) and analyzed with Tobit regression models, constraining each indicator’s loading and intercept to equality over the 2 groups and time periods. The model showed acceptable fit (Supplement 2). In addition to the 4-indicator latent construct, we tested each of the 7 end-of-life-communication items (recoded to the 0-11 scale) as separate outcomes.

Goal-Concordant Care

We assessed patient reports of goal-concordant care at 3 months after the target visit with 2 questions from SUPPORT.11,30 The first question defines patient preferences for either extending life or ensuring comfort: “If you had to make a choice at this time, would you prefer a plan of medical care that focuses on extending life as much as possible, even if it means having more pain and discomfort, or would you want a plan of medical care that focuses on relieving pain and discomfort as much as possible, even if that means not living as long?” The second question assesses patients’ perceptions of their current treatment with the same choices.30 Our outcome was a dichotomous variable measuring whether the preference matched the patient’s report of current care. Although many patients want both comfort and life-extending care, this “forced choice” requirement to pick one or the other is a useful way to identify patients’ top priority.31,32,33 If patients indicated “I do not know” for either preference or current care, this was coded as inconsistent with goal-concordant care.

Depression

Symptoms of depression were evaluated using 2 measures based on the 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8).34,35 The PHQ-8 has good reliability, sensitivity, and specificity,36 demonstrated validity,37 and responsiveness to interventions.38 The PHQ-8 score sums symptoms with higher scores indicating worse symptoms.39,40 However, results of CFA of the 8 items, defined as ordered categorical variables and analyzed with probit regression, showed significant departure from unidimensionality in our sample at all assessment points (baseline: n = 491, χ220 = 82.622, P < .001; 3 months: n = 370, χ220 = 90.973, P < .001; 6 months: n = 327, χ220 = 53.007, P < .001).41 Despite this, we report results for the standard PHQ-8 score for comparability with other studies; the score was computed for all respondents answering at least 7 items, with scores for patients answering only 7 items weighted to compensate for the missing item. In addition, we used CFA to analyze the PHQ-2, a 2-item abbreviated measure of depressive symptoms.42 A latent construct based on these 2 items, with scalar measurement invariance imposed between groups (intervention and control) and over 3 time periods (baseline, 3-month, 6-month), constrained each indicator’s loadings and thresholds to equality between groups and over time. This model showed acceptable fit (Supplement 2). The PHQ-8 composite score and the 2-indicator latent variable were evaluated at both 3 and 6 months after the target visit.

Anxiety

Symptoms of anxiety were evaluated using 2 measures based on the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder survey (GAD-7). The GAD-7 demonstrates good psychometric characteristics including reliability, test-retest stability, sensitivity, specificity, validity, and responsiveness to nonpharmacological interventions.40,43,44,45,46,47 As with the PHQ-8, the standard GAD-7 score did not exhibit unidimensionality in our sample at any of the 3 assessment points, based on CFA (baseline: n = 491, χ214 = 36.855, P < .001; 3 months: n = 371, χ214 = 75.063, P < .001; 6 months: n = 332, χ214 = 95.087, P < .001), but we report this outcome for comparability to other studies. The GAD-7 scale was computed if the respondent had no missing data or missing data on only 1 item, and it was weighted if 1 item was missing. We also investigated whether a construct based on a smaller number of indicators might provide an appropriate latent measure. Using exploratory factor analysis in a CFA framework48 and beginning with all 7 items, we identified a 2-indicator construct (items 1 and 3, defined as ordered categorical variables and analyzed with probit regression), with acceptable fit (Supplement 2). The GAD-7 composite score and the 2-indicator latent variable were evaluated at 3 and 6 months.

Sample Size

When the study was initiated, sample size calculations for the primary outcome were based on the prior trial.18 We estimated power to detect a significant difference in the occurrence of a goals-of-care discussion among patients who did not report that they wanted to avoid such a discussion. Based on the prior study, we estimated that two-thirds of patients would want a goals-of-care discussion with the clinician and that 12.8% of control patients and 30.0% of intervention patients would report that discussions had occurred. Based on these projections, we targeted recruitment of 120 clinicians with 6 patients each (4 of whom would want a discussion) to produce more than 95% power for detecting the anticipated difference. Because of difficulties reaching target enrollment, we performed an interim evaluation of the overall proportion of patients reporting a goals-of-care discussion and found higher proportions than we had estimated, and we reassessed our target sample size to 120 clinicians and 500 patients. This change was approved by the Data Safety Monitoring Board and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Randomization and Blinding

We randomized clinicians at a 1:1 ratio with the primary outcome at the level of the patient. Randomization was stratified by site with randomly assigned block sizes, using computer-generated random number sequences. We were unable to blind clinicians or patients, but staff members assessing outcomes were blinded to treatment allocation.

Statistical Methods

All analyses testing intervention effects were restricted to 494 patients who completed the target visit or to subsamples of that group. Subsamples included patients who did not object at baseline to future goals-of-care discussions with the clinician (for analysis of the occurrence-of-discussion outcome) and patients with stable goals of care (for analysis of the goal-concordant care outcome). All models included clustering of patients by treating clinician, using Mplus-estimated complex models, which correct standard errors for nonindependence of observations within clusters. A 2-sided P < .05 signified statistical significance. Binary and ordered categorical outcomes were tested with probit regression models using a weighted-least-squares estimator with mean and variance adjustment (WLSMV); censored outcomes (QOC ratings and the GAD-7 total score), with Tobit regression estimated with WLSMV; and linear outcomes (PHQ-8 total score), with robust linear regression estimated with restricted maximum likelihood.

All analyses included covariate adjustment for the baseline measure of the outcome and adjustment for other variables found to confound the association between randomization group and outcome. We tested 12 variables as potential confounders: patient age, sex, racial/ethnic minority status, marital status, education, self-perceived health status, and income; clinician type (physician or nurse practitioner), specialty, age, sex, and racial/ethnic minority status. We deemed a variable as a confounder and included it in the final model if adding it to the bivariate model changed the coefficient for treatment group by more than 10%.49,50,51

We had complete data for the primary outcome for 80% of patients randomized, but 83% of the sample had missing data on 1 or more of the 51 outcomes and confounders in our analyses (41% failing to return at least 1 survey and the remainder having 1 or more missing items on surveys). We repeated all analyses using multiple imputation, building 83 data sets for similarity to the percentage of incomplete cases.52,53,54 The complete-case and multiple-imputation analyses gave similar results, so only the complete-case analyses are shown. We used IBM SPSS software, version 19 for descriptive statistics and Mplus, version 8 for all other analyses.

Results

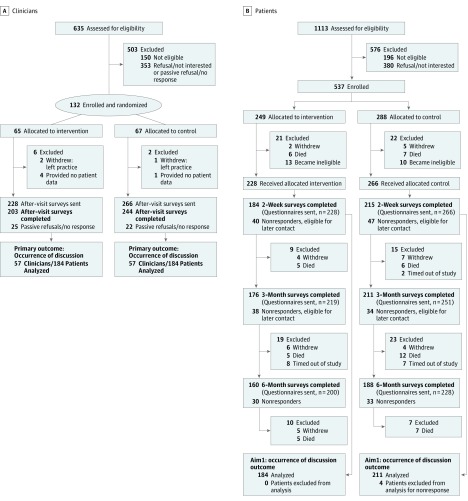

Of 485 potentially eligible clinicians, we enrolled 132 (27% participation) with 65 randomized to intervention and 67 to usual care (Figure 1A). Of these 132 clinicians, 124 had patients participating in the study (3 clinicians changed practices, and 5 had no patients enrolled). We identified 917 eligible patients, of whom 537 enrolled (59% participation) with 249 allocated to intervention and 288 to usual care (Figure 1B). Of these 537 patients, 494 contributed outcome data (23 became ineligible, 13 died, and 7 withdrew). Clinicians were recruited between February 2014 and November 2015; patients, between March 2014 and May 2016.

Figure 1. Study Enrollment and Participation Flowcharts.

A, Clinician randomization and participation. B, Patient enrollment and participation. Patient nonresponders included those who (1) refused or passively refused (sent no response); (2) were unreachable; and (3) were ill or hospitalized.

A slight majority of clinicians were women (53%; n = 66) with an average age of 47.2 years (Table 1). A slight majority of patients were men (52%; n = 259) with an average age of 73.5 years (Table 1). The most common chronic illness was advanced cancer (18%; n = 90). Patients were predominantly non-Hispanic white (79%; n = 391), and 45% (n = 222) reported fair to poor health status.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Clinicians and Patientsa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Clinicians (n = 124) | |

| Racial/ethnic minority | 30 (24.2) |

| Female | 66 (53.2) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 47.2 (9.6) |

| Type | |

| Physician | 115 (92.7) |

| Nurse practitioner | 9 (7.3) |

| Specialty | |

| Family medicine | 29 (23.4) |

| Internal medicine | 34 (27.4) |

| Oncology | 24 (19.4) |

| Pulmonology | 8 (6.5) |

| Cardiology | 16 (12.9) |

| Gastroenterology | 3 (2.4) |

| Nephrology | 7 (5.6) |

| Geriatrics | 3 (2.4) |

| Patients (n = 494) | |

| Racial/ethnic minority | 103 (20.9) |

| Female | 235 (47.6) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 73.5 (12.6) |

| Educationb | |

| Eighth grade or less | 12 (2.4) |

| Some high school | 29 (5.9) |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 68 (13.8) |

| Trade school or some college | 202 (41.0) |

| Four-year college degree | 83 (16.8) |

| Some graduate school | 23 (4.7) |

| Graduate degree | 76 (15.4) |

| Marital statusb | |

| Never married | 66 (13.4) |

| Married or living with partner | 222 (45.0) |

| Divorced or separated | 98 (19.9) |

| Widowed | 107 (21.7) |

| Average monthly pretax income in last 3 years, $b | |

| None | 3 (0.7) |

| 1-500 | 4 (0.9) |

| 501-1000 | 58 (12.6) |

| 1001-1500 | 48 (10.4) |

| 1501-2000 | 50 (10.9) |

| 2001-3000 | 72 (15.7) |

| 3001-4000 | 63 (13.7) |

| 4001 or more | 162 (35.2) |

Data are from the records of 494 patients and 124 clinicians for whom a target visit occurred.

Missing data on education and marital status for 1 patient; missing data on income for 34 patients.

Among clinicians, participation rates did not differ significantly by racial/ethnic minority status, sex, age, or type. However, as detailed with the data reported in eTable 2 in Supplement 2, it did differ significantly by physician specialty, with higher participation rates seen for clinicians in pulmonary medicine and oncology and lower rates for clinicians in family practice. Patient participation did not differ significantly by qualifying conditions, racial/ethnic minority status, sex, or age (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

The Jumpstart-Tips intervention was associated with increased occurrence and quality of goals-of-care discussions at the target clinic visit (Table 2). Occurrence of such discussions was more likely in the intervention group among all patients (74%, n = 137 vs 31%, n = 66; P < .001) and also among the subset of patients who did not explicitly report that they wanted to avoid such a discussion (78%, n = 112 vs 28%, n = 44; P < .001). Participating clinicians’ EHR documentation of a goals-of-care discussion was also higher for the intervention group among all patients (62%, n = 140 vs 17%, n = 45; P < .001), with similar findings for patients who did not explicitly report a desire to avoid discussion (63%, n = 114 vs 17%, n = 34; P < .001).

Table 2. Effect of the Intervention on Occurrence and Quality of Patient-Clinician Communication About Advance-Care Planninga.

| Outcome | Patients/Clinicians, No.b | Target Visit, Percentage or Mean (95% CI)c | β (95% CI)d | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | ||||

| Patient Report of Occurrence of a Goals-of-Care Discussion at Clinic Visit, % | |||||

| All patientse,f,g | 395/121 | 31 (25 to 38) | 74 (68 to 81) | 1.25 (0.94 to 1.56) | <.001 |

| Patients who did not object to discussione,f,h | 303/115 | 28 (21 to 35) | 78 (72 to 85) | 1.47 (1.13 to 1.81) | <.001 |

| EHR Documentation of Goals-of-Care Discussion at Clinic Visit, % | |||||

| All patientse,i | 492/123 | 17 (12 to 22) | 62 (55 to 68) | 1.25 (0.92 to 1.58) | <.001 |

| Patients who did not object to discussione,i | 379/121 | 17 (12 to 22) | 63 (56 to 70) | 1.29 (0.92 to 1.66) | <.001 |

| QOC Score at Target Visit, Mean Rating | |||||

| Overall QOC about end-of-life issues | |||||

| 4-Indicator construct—items most supported by the interventionj | 268/108 | 2.13 (1.00 to 3.25) | 4.59 (1.75 to 7.42) | 2.02 (0.48 to 3.57) | .01 |

| Individual QOC itemsk | |||||

| 1. Talking about patient’s feelings about getting sickerl | 338/116 | 6.30 (5.60 to 6.99) | 7.70 (7.06 to 8.37) | 2.209 (0.934 to 3.48) | .001 |

| 2. Talking about details of getting sickerm | 338/117 | 5.95 (5.25 to 6.62) | 6.96 (6.25 to 7.66) | 1.24 (−0.33 to 2.80) | .12 |

| 3. Talking about how long patient might have to liven | 345/118 | 3.43 (2.76 to 4.10) | 4.03 (3.28 to 4.77) | 2.34 (−0.426 to 5.08) | .10 |

| 4. Talking about what dying might be likeo | 353/119 | 2.10 (1.53 to 2.66) | 2.23 (1.60 to 2.86) | 1.57 (−1.74 to 4.89) | .35 |

| 5. Discussing patient’s wishes for end-of-life treatmentl | 340/115 | 4.50 (3.77 to 5.23) | 6.72 (5.97 to 7.48) | 4.63 (2.06 to 7.19) | <.001 |

| 6. Asking about things in life that are important to patientl | 351/120 | 5.64 (4.92 to 6.36) | 7.15 (6.47 to 7.82) | 2.40 (0.90 to 3.91) | .002 |

| 7. Asking about patient’s spiritual or religious beliefsp | 347/118 | 2.43 (1.82 to 3.03) | 3.11 (2.44 to 3.88) | 2.46 (−0.25 to 5.16) | .08 |

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; QOC, quality of communication; WLSMV, weighted least squares with mean and variance adjustment.

The coefficient estimates and P values were based on complex single-group regression models with patients clustered by treating clinician, with the intervention group as the predictor of interest, and with adjustment for any variables that confounded the association between the intervention-group predictor and outcome. A variable was identified as a confounder if its addition to the bivariate model changed the coefficient for the intervention group by 10% or more in either direction. For all outcomes, patients were included only if they provided data for the outcome and any covariates in the model.

Number of patients/number of clinician clusters.

For occurrence of discussion, the unadjusted percentage is the percentage of each group with a qualifying discussion; for the individual QOC items, the unadjusted mean is the mean outcome at the target visit. For the multi-indicator construct, the mean of the construct on the after-visit questionnaire, based on a 2-group CFA model using patients with complete data for all 4 indicators at baseline and after visit, with scalar measurement invariance imposed between groups and over time, and with the baseline mean for the control group fixed at 0.

Point estimate and confidence interval for regression coefficient from single-group model with outcome regressed on the intervention-group predictor, adjusted for any confounders.

Binary outcome modeled with probit regression, estimated with WLSMV.

Adjusted for occurrence of discussion prior to study enrollment.

A supplementary analysis included 369 patients, excluding patients in the intervention group whose clinicians did not report whether they had used the Jumpstart-Tips form. Compared with patients in the control group, and adjusting for occurrence of discussion prior to enrollment, patients whose clinicians did not use the Jumpstart-Tips form (n = 20) were somewhat, although not significantly, more likely to report a discussion (β = 0.57, P = .07), whereas those whose clinicians used the Jumpstart-Tips form (n = 138) were significantly more likely to report a discussion (β = 1.46, P < .001).

A supplementary analysis included 280 patients, excluding patients in the intervention group whose clinicians did not report whether they had used the Jumpstart-Tips form. Compared with patients in the control group, and adjusting for occurrence of discussion prior to enrollment, both patients whose clinicians did not use the Jumpstart-Tips form (n = 12, β = 0.90, P = .02) and those whose clinicians used the Jumpstart-Tips form (n = 108, β = 1.65, P < .001) were significantly more likely to report a discussion at the target visit.

No confounders; bivariate model. (No adjustment was made for documentation of discussions prior to the patient’s study enrollment because chart abstractions did not extend back to the preenrollment period.)

Based on cases with complete data for all 4 indicators at both time points. Ordered categorical indicators modeled with probit regression and estimated with weighted least squares with mean and variance adjustment; adjusted for the baseline level on the construct.

Outcomes (0-11 ratings) defined as censored from below and modeled with Tobit regression, estimated with WLSMV.

Adjusted for baseline value on the outcome variable.

Adjusted for baseline value on the outcome variable and clinician specialty.

Adjusted for baseline value on the outcome variable, clinician type, and clinician specialty.

Adjusted for baseline value on the outcome variable, patient racial/ethnic minority status, education, and income; clinician type and specialty.

Adjusted for baseline value on the outcome variable and clinician type.

Quality ratings of goals-of-care discussions at the target visit were higher in the intervention group than in the control group (mean values, 4.6 vs 2.1, P = .01, on the 4-indicator construct). As detailed by the data reported in Table 2, of the 7 individual quality-of-communication items, the intervention group reported significantly higher ratings on 3 items, with no significant differences for the other 4 items.

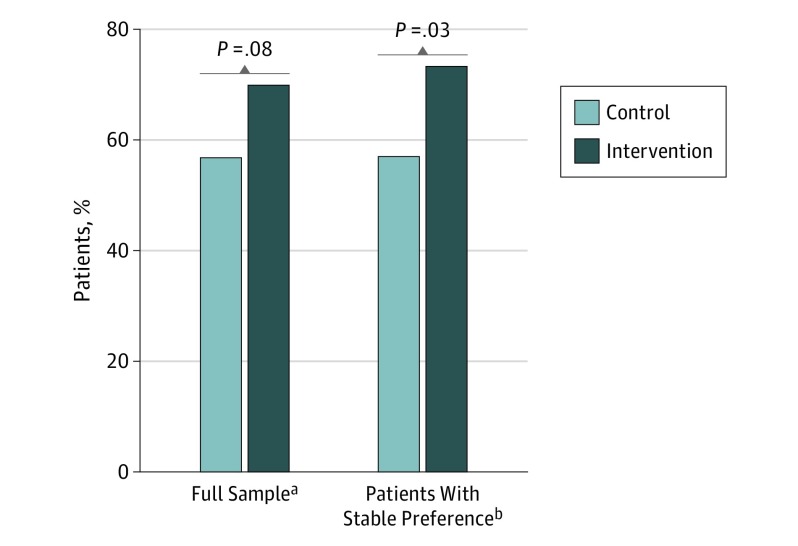

Three months after the target visit, patients’ reports of their primary health care goal (comfort vs life extension) and the primary focus of their current care showed a nonsignificant treatment effect on goal-concordant care (70%, n = 91 intervention vs 57%, n = 83 control; P = .08). However, among patients whose goals were stable between the 3-month follow-up and their last prior assessment, the treatment effect was significant (73%, n = 72 intervention vs 57%, n = 57 control; P = .03; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percentage of Patients Reporting Goal-Concordant Care 3 Months After Target Visit.

aFull sample based on 277 patients with a stated preference at 3 months and adequate information to assess goal-concordant care at baseline. Complex probit regression model with patients clustered by treating clinician (n = 114 clinicians) and adjusted for treatment preference (life extension or comfort care) at 3 months and concordance at baseline produced β = 0.333 (95% CI, −0.036 to 0.702; P = .08).

bPatients with stable preference based on 198 patients with a stated preference at 3 months, a goal of care that was stable from target visit to 3-month follow-up (or from baseline to 3-month follow-up if no after-visit questionnaire was returned), and with adequate information to assess goal-concordant care at baseline. Complex probit regression model with patients clustered by treating clinician (n = 100 clinicians) and adjusted for treatment preference (life extension or comfort care) at 3 months, concordance at baseline, and clinician type (physician or nurse practitioner) produced β = 0.451 (95% CI, 0.047-0.855; P = .03).

As detailed by the data reported in Table 3, symptoms of depression or anxiety at 3 or 6 months did not vary significantly by intervention vs control group as assessed by the standard composite scores or the 2-indicator latent variables. In addition, we found no evidence of significant differences for each individual item on these 2 measures (data not shown).

Table 3. Effect of the Intervention on Patients’ Symptoms of Depression and Anxietya.

| Outcome | Patients/Clinicians, No.b | Mean Value for Psychological Symptoms (95% CI) at Follow-upc | β (95% CI)d | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | ||||

| Depression Symptoms | |||||

| 3 Months after target visit | |||||

| 2-Indicator latent variablee,f | 262/113 | 0.20 (−0.02 to 0.42) | 0.26 (−0.04 to 0.55) | −0.10 (−0.33 to 0.12) | .37 |

| Standard PHQ-8 composite scoreg,h | 359/119 | 4.88 (4.23 to 5.54) | 5.92 (5.19 to 6.66) | 0.26 (−0.57 to 1.10) | .54 |

| 6 Months after target visit | |||||

| 2-Indicator latent variablee,i | 262/113 | 0.24 (0.07 to 0.42) | 0.40 (0.11 to 0.69) | 0.21 (−0.04 to 0.46) | .11 |

| Standard PHQ-8 Composite Scoreg,j | 314/118 | 4.84 (4.17 to 5.51) | 5.927 (5.05 to 6.81) | 0.45 (−0.48 to 1.37) | .34 |

| Anxiety Symptoms | |||||

| 3 Months after target visit | |||||

| 2-Indicator latent variablee,h | 277/119 | 0.22 (0.01 to 0.43) | 0.28 (−0.04 to 0.60) | −0.03 (−0.23 to 0.16) | .73 |

| Standard GAD-7 composite scoreh,k | 366/122 | 3.00 (2.44 to 3.57) | 3.26 (2.64 to 3.89) | 0.04 (−0.95 to 1.03) | .94 |

| 6 Months after target visit | |||||

| 2-Indicator latent variablee,h | 277/119 | 0.21 (−0.05 to 0.47) | 0.30 (0.00 to 0.59) | −0.04 (−0.25 to 0.16) | .69 |

| Standard GAD-7 composite scoreh,k | 327/119 | 3.08 (2.44 to 3.72) | 3.375 (2.67 to 4.08) | −0.11 (−1.20 to 1.00) | .85 |

Abbreviations: CFA, confirmatory factor analysis; GAD-7, 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder survey; PHQ-8, 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire; WLSMV, weighted least squares with mean and variance adjustment.

The coefficient estimates and P values were based on complex single-group regression models with patients clustered by treating clinician, with intervention group as the predictor of interest, and with adjustment for any variables that confounded the association between the intervention-group predictor and outcome. A variable was identified as a confounder if its addition to the bivariate model changed the coefficient for the intervention group by 10% or more in either direction. For the latent variable outcomes, the sample included only those patients who provided data for both indicators at all 3 time points (baseline, 3-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up). For all outcomes, patients were included only if they provided data for the outcome and any covariates in the model.

Number of patients/number of clinician clusters.

For the standard composite scores, the unadjusted mean for the standard composite score, computed with data from the follow-up questionnaire. For the 2-indicator constructs, the mean value of the construct on the follow-up questionnaire, based on a 2-group CFA model using patients with complete data for the 3 time periods, with scalar measurement invariance imposed between groups and over time, and with the baseline mean for the control group fixed at 0.

Point estimate and confidence interval for the regression coefficient from a single-group model with the outcome regressed on the intervention-group predictor, after adjustment for any confounders.

Probit regression model, estimated with WLSMV.

Adjusted for baseline level on the outcome and the patient’s racial/ethnic minority status.

Robust linear regression model, estimated with restricted maximum likelihood.

Adjusted for baseline level on the outcome.

Adjusted for patient’s baseline level on the outcome, age, racial/ethnic minority status, education, and self-identified health status; and for clinician type and specialty.

Adjusted for patient’s baseline level on the outcome and clinician specialty.

The outcome was defined as censored from below; Tobit regression model estimated with WLSMV.

Of 203 after-visit surveys returned by clinicians in the intervention group, 194 indicated whether they used the Jumpstart-Tips form, with 158 (81%) indicating use of the form and 36 (19%) indicating nonuse. The intervention effect was stronger among patients whose clinicians reported using the form (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

There was not consistent evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effects for the outcomes by patient diagnosis (cancer vs no cancer; heart disease vs no heart disease; and lung disease vs no lung disease; eTables 4-6 in Supplement 2). Of these tests for interaction, only 1 statistically significant interaction yielded a significant within-stratum treatment effect: among patients with cancer, the intervention was associated with increased symptoms of anxiety at 3 months but not 6 months (data detailed in eTable 4 in Supplement 2). There were no significant interactions between the intervention and patient self-reported health status or patients’ baseline ratings of clinician communication (eTables 7 and 8 in Supplement 2).

Qualitative data collected from 10 patients, 5 family members, and 10 clinicians suggest that the intervention was viewed as helpful, increased all involved persons’ awareness of the importance of goals-of-care discussions, and assisted in opening this discussion (Supplement 2).

Discussion

Prompting goals-of-care communication is a high priority in the care of patients with serious illness because it offers opportunities for patients to identify their goals and for clinicians and patients to jointly facilitate goal attainment.10,55,56 This preconversation, patient-specific communication-priming intervention was associated with increased goals-of-care communication during routine clinic visits between patients with serious illness and clinicians, as measured by patient report and clinician documentation. The improvements associated with the intervention occurred despite a control group showing rates of goals-of-care discussion higher than seen in prior studies.4,18 In addition, the intervention was associated with higher ratings of the quality of this communication as assessed by patients. This intervention could be used in conjunction with other recent approaches to improve goals-of-care and advance care planning, such as clinician training,57,58,59,60,61 informational videos,62,63,64 and web-based advance care planning.65,66

Prior to their clinic visit, 23% of patients (n = 191) reported that they did not want to have a goals-of-care discussion. We examined differences in goals-of-care discussions for all patients as well as for those who did not explicitly report that they wanted to avoid such a discussion. Although avoiding discussions that are undesired by patients may be more patient centered, there may be value in raising these issues even with reluctant patients.27,28,67 The Jumpstart-Tips intervention alerted clinicians when patients were reluctant to discuss goals of care and provided tailored recommendations (for example, an indirect approach to discussing prognosis).27

In prior studies, goals-of-care communication has been associated with improved patient and family outcomes, including increased satisfaction with care and reduced intensity of care at the end of life.1,2,3,14 Our study was not powered to investigate changes in end-of-life care: only 40 patients died during the study. Further studies are needed to determine whether this intervention results in changes in end-of-life care. However, the intervention was associated with increased patient-reported goal-concordant care at 3-month follow-up among patients with stable goals. We believe the analysis limited to patients with stable goals represents a realistic expectation for the intervention’s effect: concordance is difficult to assess for patients whose goals vacillate over time because the focus of recent care may reflect out-of-date goals from the near past. By contrast, the analysis limited to these patients focuses on patients likely to state consistent goals, facilitating clinicians’ design of care to achieve those goals. Finally, a previous intervention to promote goals-of-care communication was associated with a small increase in depressive symptoms among patients.13 In the current study, we did not see evidence that facilitating these discussions among practicing clinicians was associated with an increase in symptoms of depression. There was some evidence of increased symptoms of anxiety among patients with cancer, but given the multiple comparisons in the analyses for heterogeneity of treatment effects, these findings should be viewed as hypothesis generating. Future studies should continue to evaluate the effect of interventions to promote goals-of-care discussions on patients’ psychological symptoms.

Implementation of this intervention into clinical practice would require creating or repurposing resources used to identify and survey eligible patients. The creation of the Jumpstart-Tips forms could be automated from the algorithm we used (Supplement 2) and health care systems may want to adapt or update this algorithm using local palliative care expertise and norms.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations. First, although this is a multicenter study with diverse health care institutions, it took place in 1 region of the United States and may not generalize elsewhere. Second, there may be selection bias among clinicians and patients willing to participate. We identified few variables associated with participation, but there may be differences in unmeasured variables. Willingness to participate, especially among busy clinicians, may have been limited because this was a randomized trial where the control arm received nothing beyond surveys; a phase 4 evaluation of this intervention is needed to determine the barriers to implementation and dissemination. In addition, it is important to acknowledge that a clinician reluctant to participate may not receive the same benefit from the intervention. Third, measurement of goal-concordant care is a novel and challenging area of palliative-care research and requires further study.68,69 Our approach may be limited by patients’ awareness of their goals and their ability to discern the focus of their current care. However, patient perceptions of both their goals and the focus of their care are important aspects of goal-concordant care.69 Finally, we did not assess prior communication training for clinicians, which could influence intervention effectiveness. However, we did not observe any evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effects by patients’ baseline ratings of clinicians’ communication about palliative care.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the patient-specific Jumpstart-Tips intervention was associated with an increase in patient reports and clinician documentation of goals-of-care communication between patients with serious illness and primary and specialty care clinicians. This intervention was also associated with increased patient-reported goal-concordant care among patients with stable goals, suggesting enhanced patient-centered care. The intervention was not associated with a change in symptoms of depression or anxiety. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether this communication is associated with changes in health care delivery.

Trial Protocol

A. Patient Surveys

B. Jumpstart-Tips

C. Resources for Intervention Implementation [eTable 1]

D. Supplementary Analyses

1. Confirmatory factor analysis results for the quality of communication 4-item scale, PHQ-2, and GAD-2

2. Clinician and patient characteristics for participants and non-participants [eTable 2]

3. Associations between use of Jumpstart-Tips forms at target visit and occurrence of goals-of-care discussion [eTable 3]

4. Results of HTE analyses for five predictors

a. Patient diagnosis (cancer vs. no cancer) [eTable 4]

b. Patient diagnosis (heart disease vs. no heart disease) [eTable 5]

c. Patient diagnosis (lung disease vs. no lung disease) [eTable 6]

d. Patient’s baseline self-assessed health status [eTable 7]

e. Patient’s baseline rating of clinician’s quality of communication [eTable 8]

E. Qualitative Data: methods, analyses and findings

References

- 1.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. . Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315(3):284-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. . Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. . Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):480-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, Au DH, Patrick DL. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(2):200-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Understanding physicians’ skills at providing end-of-life care perspectives of patients, families, and health care workers. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(1):41-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tulsky JA, Chesney MA, Lo B. See one, do one, teach one? house staff experience discussing do-not-resuscitate orders. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(12):1285-1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickson RP, Engelberg RA, Back AL, Ford DW, Curtis JR. Internal medicine trainee self-assessments of end-of-life communication skills do not predict assessments of patients, families, or clinician-evaluators. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(4):418-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, Lettang K, Meier DE, Morrison RS. The growth of palliative care in U.S. hospitals: a status report. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(1):8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumanovsky T, Rogers M, Spragens LH, Morrison RS, Meier DE. Impact of staffing on access to palliative care in U.S. hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(12):998-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meier DE, Back AL, Berman A, Block SD, Corrigan JM, Morrison RS. A national strategy for palliative care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(7):1265-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The SUPPORT Principal Investigators A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: the study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591-1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneiderman LJ, Kronick R, Kaplan RM, Anderson JP, Langer RD. Effects of offering advance directives on medical treatments and costs. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(7):599-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, et al. . Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2271-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Shannon SE, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Communicating with dying patients within the spectrum of medical care from terminal diagnosis to death. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):868-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Ambrozy DA, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ramsey PG. Dying patients’ need for emotional support and personalized care from physicians: perspectives of patients with terminal illness, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(3):236-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dow LA, Matsuyama RK, Ramakrishnan V, et al. . Paradoxes in advance care planning: the complex relationship of oncology patients, their physicians, and advance medical directives. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):299-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Au DH, Udris EM, Engelberg RA, et al. . A randomized trial to improve communication about end-of-life care among patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;141(3):726-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA. Heart failure. Lancet. 2005;365(9474):1877-1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connors AF Jr, Dawson NV, Thomas C, et al. . Outcomes following acute exacerbation of severe chronic obstructive lung disease. The SUPPORT investigators (Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(4, pt 1):959-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Hays JC, et al. . Identifying, recruiting, and retaining seriously-ill patients and their caregivers in longitudinal research. Palliat Med. 2006;20(8):745-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV, Vangeli M, Terreni N, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Systematic review: the model for end-stage liver disease—should it replace Child-Pugh’s classification for assessing prognosis in cirrhosis? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(11-12):1079-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knauft E, Nielsen EL, Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Barriers and facilitators to end-of-life care communication for patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;127(6):2188-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell E, Collier AC. Why don’t patients and physicians talk about end-of-life care? barriers to communication for patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and their primary care clinicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1690-1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Patients’ perspectives on physician skill in end-of-life care: differences between patients with COPD, cancer, and AIDS. Chest. 2002;122(1):356-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtis JR, Engelberg R, Young JP, et al. . An approach to understanding the interaction of hope and desire for explicit prognostic information among individuals with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(4):610-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Back AL, Arnold RM. Discussing prognosis: “how much do you want to know?” talking to patients who do not want information or who are ambivalent. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(25):4214-4217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(5):1086-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teno JM, Fisher ES, Hamel MB, Coppola K, Dawson NV. Medical care inconsistent with patients’ treatment goals: association with 1-year Medicare resource use and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):496-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coast J, Huynh E, Kinghorn P, Flynn T. Complex valuation: applying ideas from the Complex Intervention Framework to valuation of a new measure for end-of-life care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(5):499-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finkelstein EA, Bilger M, Flynn TN, Malhotra C. Preferences for end-of-life care among community-dwelling older adults and patients with advanced cancer: a discrete choice experiment. Health Policy. 2015;119(11):1482-1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flynn TN, Bilger M, Malhotra C, Finkelstein EA. Are efficient designs used in discrete choice experiments too difficult for some respondents? a case study eliciting preferences for end-of-life care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(3):273-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Löwe B, Gräfe K, Kroenke K, et al. . Predictors of psychiatric comorbidity in medical outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(5):764-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Gräfe K, et al. . Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. J Affect Disord. 2004;78(2):131-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4488-4496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Downey L, Hayduk LA, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. Measuring depression-severity in critically ill patients’ families with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): tests for unidimensionality and longitudinal measurement invariance, with implications for CONSORT. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(5):938-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. . Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richards DA, Borglin G. Implementation of psychological therapies for anxiety and depression in routine practice: two year prospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2011;133(1-2):51-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dear BF, Titov N, Sunderland M, et al. . Psychometric comparison of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for measuring response during treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2011;40(3):216-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. 2nd ed New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(3):340-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(1):125-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Muller K. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods. 2nd ed Boston, MA: PWS-Kent Publishing Co; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bodner TE. What improves with increased missing data imputations? Struct Equ Modeling. 2008;15:651-675. [Google Scholar]

- 53.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allison P. Why you probably need more imputations than you think. 2012. https://statisticalhorizons.com/more-imputations. Accessed January 25, 2018.

- 55.Institute of Medicine Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tulsky JA, Beach MC, Butow PN, et al. . A research agenda for communication between health care professionals and patients living with serious illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1361-1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. . Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):453-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bays A, Engelberg RA, Back AL, et al. . Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: evaluation of small group, simulated patient interventions. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(2):159-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bernacki RE, Block SD; American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force . Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1994-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lakin JR, Koritsanszky LA, Cunningham R, et al. . A systematic intervention to improve serious illness communication in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(7):1258-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. . Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(9):593-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Volandes AE, Brandeis GH, Davis AD, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of a goals-of-care video for elderly patients admitted to skilled nursing facilities. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(7):805-811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Davis AD, Eubanks R, El-Jawahri A, Seitz R. Use of video decision aids to promote advance care planning in Hilo, Hawai’i. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1035-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Mitchell SL, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of a video decision support tool for cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making in advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(3):380-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sudore RL, Barnes DE, Le GM, et al. . Improving advance care planning for English-speaking and Spanish-speaking older adults: study protocol for the PREPARE randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sudore RL, Boscardin J, Feuz MA, McMahan RD, Katen MT, Barnes DE. Effect of the PREPARE website vs an easy-to-read advance directive on advance care planning documentation and engagement among veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1102-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jacobsen J, Brenner K, Greer JA, et al. . When a patient is reluctant to talk about it: a dual framework to focus on living well and tolerate the possibility of dying. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(3):322-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Turnbull AE, Hartog CS. Goal-concordant care in the ICU: a conceptual framework for future research. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1847-1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA. Achieving goal-concordant care: a conceptual model and approach to measuring serious illness communication and its impact. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S17-S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

A. Patient Surveys

B. Jumpstart-Tips

C. Resources for Intervention Implementation [eTable 1]

D. Supplementary Analyses

1. Confirmatory factor analysis results for the quality of communication 4-item scale, PHQ-2, and GAD-2

2. Clinician and patient characteristics for participants and non-participants [eTable 2]

3. Associations between use of Jumpstart-Tips forms at target visit and occurrence of goals-of-care discussion [eTable 3]

4. Results of HTE analyses for five predictors

a. Patient diagnosis (cancer vs. no cancer) [eTable 4]

b. Patient diagnosis (heart disease vs. no heart disease) [eTable 5]

c. Patient diagnosis (lung disease vs. no lung disease) [eTable 6]

d. Patient’s baseline self-assessed health status [eTable 7]

e. Patient’s baseline rating of clinician’s quality of communication [eTable 8]

E. Qualitative Data: methods, analyses and findings