This historical control study examined the association of a 2-year early intervention service with suicide reduction in patients with first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and the risk factors for early and late suicide.

Key Points

Questions

Is an early intervention service associated with a reduction in the long-term suicide rate in patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders?

Findings

In this historical control study of 1234 patients with first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (617 each in the early intervention and standard care groups), patients receiving a 2-year early intervention service had a significantly lower suicide rate during 12 years, with the main difference observed during the first 3 years.

Meaning

An early intervention service may be associated with reductions in the suicide rate among patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders during their most vulnerable period, and the benefits may persist in the long term.

Abstract

Importance

Patients with schizophrenia have a substantially higher suicide rate than the general public. Early intervention (EI) services improve short-term outcomes. However, little is known about the association of EI with suicide reduction in the long term.

Objective

To examine the association of a 2-year EI service with suicide reduction in patients with first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum (FES) disorders during 12 years and the risk factors for early and late suicide.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This historical control study compared 617 consecutive patients with FES who received the 2-year EI service in Hong Kong between July 1, 2001, and June 30, 2003, with 617 patients with FES who received standard care (SC) between July 1, 1998, and June 30, 2001, matched individually. Clinical information was systematically retrieved for the first 3 years of clinical care for both groups. The details of death were collected up to 12 years from presentation to the services. Data analysis was performed from October 30, 2016, to August 18, 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Suicide rate during 12 years was the primary measure. The association of the EI service with the suicide rates during years 1 through 3 and years 4 through 12 were explored separately.

Results

The main analysis included 1234 patients, with 617 in each group (mean [SD] age at baseline, 21.2 [3.4] years in the EI group and 21.3 [3.4] years in the SC group; 318 male [51.5%] in the EI group and 322 [52.2%] in the SC group). The suicide rates were 7.5% in the SC group and 4.4% in the EI group (McNemar χ2 = 5.55, P = .02). Patients in the EI group had significantly better survival (propensity score–adjusted hazard ratio, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.36-0.91; P = .02), with the maximum association observed in the first 3 years. The number of suicide attempts was an indicator of early suicide (1-3 years). Premorbid occupational impairment, number of relapses, and poor adherence during the initial 3 years were indicators of late suicide (4-12 years).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study suggests that the EI service may be associated with reductions in the long-term suicide rate. Suicide at different stages of schizophrenia was associated with unique risk factors, highlighting the importance of a phase-specific service.

Introduction

Patients with schizophrenia have a substantially higher mortality rate and suicide rate in particular than the general population.1,2 A systematic review1 suggested that the median standardized mortality ratio (SMR) for all-cause mortality among patients with schizophrenia was 2.58 (mean, 2.98) and the median SMR for suicide was 12.86 (mean, 43.47). The lifetime risk of suicide among individuals with schizophrenia was 4% to 6%,3,4 and the population-attributable risk of suicide was estimated to be 8.9% among those with schizophrenia.5 The most accurate method to study the suicide rate would be to follow up patients with first-episode schizophrenia (FES) to avoid the selection bias of the survivors of the high-risk period immediately after the first admission. Such studies6,7,8 are relatively limited.

Many studies6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 have investigated the risk factors for suicide and suicide attempts in patients with schizophrenia. Previous systematic reviews suggested that past suicidal ideation, prior self-harm, previous depressive episode, substance misuse, poor drug adherence, and a high number of hospitalizations were risk factors for suicide attempts9 and suicides10 in patients with schizophrenia. Studies6,8,11,12,13,14 on the risk factors for suicide in first-episode psychosis (FEP) have reported that previous suicide attempts, substance misuse, young age, male sex, hopelessness, and depressive and psychotic symptoms at the first- and second-year follow-ups were significantly associated with subsequent suicide.

Knowledge about risk factors can inform the service development to reduce the suicide rate. There has been an active development of the early intervention (EI) service for FEP worldwide, with an aim to improve the outcomes for patients with psychosis.15 Despite the variation in the content of the EI services, most adopt an intensive integrated service model. Many studies have reported the benefits of an EI service in improving short-term clinical and functional outcomes, including randomized clinical trials16,17,18,19,20 and historical control studies,21,22,23 when the services were introduced as a regionwide program. Many studies24,25 found that an EI program reduced suicidal attempts, but few studies6,19,20 reported a positive outcome on reduction of completed suicide. This finding was mainly because mortality and suicide are rare events, and therefore a considerably large sample size and long follow-up are required. With a 5-year follow-up period, the OPUS study, a randomized clinical trial with the largest sample size for a randomized clinical trial comparing outcomes of EI and standard care (SC) (n = 547), did not find any statistically significant difference in the mortality or suicide rate between the EI and SC groups.6 A well-designed historical control study evaluating the long-term outcomes of a regionwide EI service can perhaps obtain a sufficient sample size to study the potential association of an EI service with the suicide rate.

Hong Kong had a population of 6.7 million in 2001. The EI service in Hong Kong, Early Assessment Service for Young People With Psychosis (EASY), was established as a regionwide service in 2001 to provide 2-year phase-specific intervention to patients with FEP in the age range of 15 to 25 years. It is an assertive intervention provided by the key workers based on a specifically developed protocol, the Psychological Intervention Program in Early Psychosis.22,26,27 The service retention rate was 87%.28 The current study aimed to evaluate the association of the EI service with the suicide rate among patients with FES disorders during a 12-year period with a large representative sample in Hong Kong. Both short- and long-term associations were evaluated. Risk factors associated with early suicide (years 1-3) and late suicide (years 4-12) were explored separately. The results of the current study can enrich our understanding of the association of an EI service with the suicide rate and provide a direction for further service development.

Methods

Study Design and Sample Identification

A historical control design was adopted because the EASY program was implemented as a regionwide service in Hong Kong in 2001.26 The samples were selected with close temporal proximity to minimize the potential cohort effect. Furthermore, 617 consecutive patients enrolled in the EASY program for the first time in the entire region between July 1, 2001, and June 30, 2003 (the first 2 years of the program), with a diagnosis of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders were identified from the centralized hospital database (Clinical Management System [CMS]). Then, 617 patients who received the standard general psychiatric service between July 1, 1998, and June 30, 2001, in the entire region matched individually by sex, diagnosis, and age were identified from the same system as the comparison group.7,8,14,22 Details of the matching process are reported in the eMethods in the Supplement. Patients with organic conditions, drug-induced psychosis, or intellectual disability (mental retardation) were excluded from the sample. Patients who had received prior psychiatric treatment for more than 1 month were also excluded. Details on the number of excluded individuals are reported in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Data analysis was performed from October 30, 2016, to August 18, 2017. The requirement of informed consent from individual patients was waived by the institutional review boards and ethics committees of the considered sites that provided institutional review board approval (Hong Kong East Cluster Research Ethics Committee, Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster, Research Ethics Committee [Kowloon Central/Kowloon East], Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee [Kowloon East Cluster], Research Ethics Committee Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical & Research Ethics Committee, and New Territories West Cluster Research Ethics Committee).

Data Collection

Mortality Information

All deaths within the cohort during the 12-year follow-up period were identified via the computerized CMS. The CMS is the centralized clinical database system for the public health care service, which is responsible for more than 90% of the hospital health care in Hong Kong. All clinical information, including mortality status, is recorded in the CMS. However, those who had emigrated and died abroad were not able to be identified. For all identified deaths, details, including the date, reason, and location of death, were obtained from the coroner’s court report. Deaths caused by intentional self-harm and events of undetermined intent were coded as suicides.29

Demographic and Clinical Information

All demographic and clinical information of 1234 patients during the initial 3 years was obtained from the CMS and written clinical records by trained researchers. Data were systematically retrieved each month for the first 3 years using a standardized data entry form based on operationalized definitions. For the patients in the EI group, this covered the 2-year EI service and the transitional year after the EI service facilitated the gradual transfer of patients to the general psychiatric service.

The demographic variables included were sex, age, and years of education. The other baseline data obtained included diagnosis, premorbid occupational functioning, age at onset, duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), number of suicide attempts during DUP, and positive, negative, and affective symptoms at onset measured with the Clinical Global Impressions–Schizophrenia (CGI-SCH) scale.30 Duration of untreated psychosis was defined as the period (in days) between the first appearance of psychotic symptoms and the use of successful psychiatric treatment as assessed by clinicians. Clinical information during the first 3 years included the number of hospitalizations, substance misuse, number of suicide attempts, number of relapses, medication adherence, clinical symptoms measured with the CGI-SCH scale, and mean defined daily dose31 of antipsychotic medication. The baseline diagnosis was determined by the clinician on the basis of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision criteria using all available clinical information. Adherence to medication for each patient was given a score of 1 to 3 for each month, and a mean of 3 years was generated, with 1 indicating good adherence and 3 indicating poor adherence. Relapse was operationally defined as a change in the CGI-SCH scores from 1 to 3 or from 4 through 6 to 5 through 7, followed by hospitalization or adjustment of antipsychotic medication.32

Validity and Reliability

Consensus meetings were conducted among the clinicians and researchers every 2 weeks during the data collection period for quality assurance. Validity and interrater reliability for major variables, including DUP and the CGI-SCH positive and negative scales, were evaluated using records of 12 patients with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) comparing the clinicians and research staff. The test results (DUP: ICC = 0.78, CGI-SCH positive: ICC = 0.89, and CGI-SCH negative: ICC = 0.77) revealed a satisfactory level of concordance.

Statistical Analysis

The SMRs and 95% CIs for all-cause mortality and suicide were calculated. Details of the calculation of the SMR are reported in the eMethods in the Supplement. The McNemar χ2 test was used to detect significant difference in suicides between groups. P < .05 (2-sided) was considered to be statistically significant.

Overall suicide survival was defined as the time between the entry point and the date of suicide death. The date of first presentation to the service was used as the entry point. Participants were censored if they did not die at the date of 12 years after the first presentation or if they died of causes other than suicide. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression accounting for correlated groups of observations33 was used to model the overall suicide survival in the 2 treatment groups with a change point at year 3 to allow for different hazards before and after this point while adjusting for sex, age, age at onset, and years of education. To compare the survival differences between the 2 treatment groups, the propensity score approach with inverse probability weighting was used to reduce the bias of nonconcurrent samples. The details of the unweighted and propensity score–reweighted patient characteristics reported according to the brief guidelines34 are given in eTable 2 in the Supplement. The propensity score–adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for year 3 or earlier and later than year 3 for suicide were reported. The number needed to treat was calculated using a parallel group approach.35 SPSS statistical software, version 23.0 (SPSS Inc) and R, version 3.3.2 (The R Foundation) were used for the statistical analysis.

Cox proportional hazards regression accounting for correlated group analysis was used to explore the association between the demographic and clinical information and the time to suicide for years 1 through 3, years 4 through 12, and the entire 12-year period. Cox proportional hazards regression considers not only time to event information but also event censoring. Patients who died during the first 3 years were excluded from the analysis of the indicators of time to suicide during years 4 through 12. Last digit carry forward was used to manage any missing variables. All statistically significant variables were used for the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression with backward selection accounting for correlated group analysis to determine the model significance with adjustment for treatment group.

Results

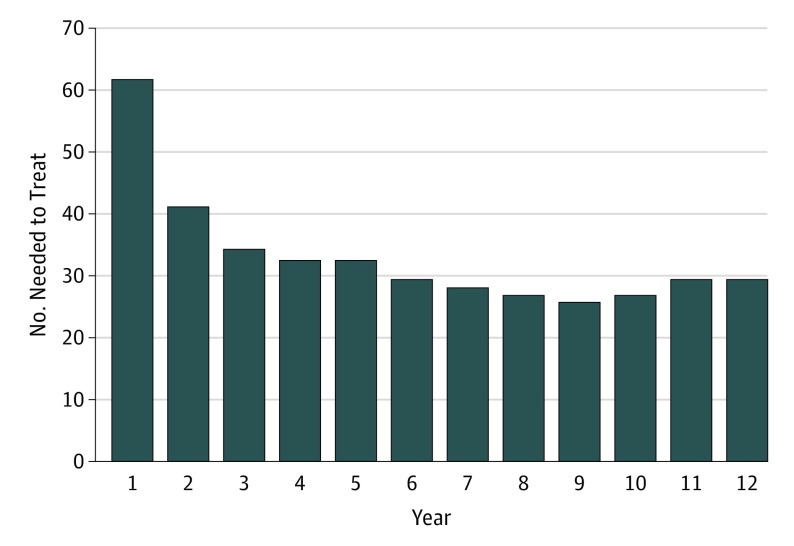

The main analysis included 1234 patients, with 617 in each group (mean [SD] age at baseline, 21.2 [3.4] years in the EI group and 21.3 [3.4] years in the SC group; 318 male [51.5%] in the EI group and 322 [52.2%] in the SC group). Baseline demographic and clinical comparisons between the groups are reported in Table 1. In all, 77 patients (6.2%) died during the 12-year period, and 73 patients (5.9%) were considered to have completed suicide, including 27 (4.4%) in the EI group and 46 (7.5%) in the SC group (McNemar’s χ2 = 5.55, P = .02). Details of cause of death and suicide are given in eTable 3 in the Supplement. The SMRs for all-cause mortality were 5.67 (95% CI, 3.84-8.09) in the EI group and 8.38 (95% CI, 6.27-10.99) in the SC group. The SMRs for suicide were 28.01 (95% CI, 18.84-40.19) in the EI group and 44.66 (95% CI, 33.08-59.06) in the SC group. The number needed to treat was 61.7 at year 1 and 29.4 at year 12, with a sharp decrease between years 1 and 3 (Figure).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the EI and SC Groupsa.

| Characteristic | EI (n = 617) | SC (n = 617) | χ2 or zb | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 21.2 (3.4) | 21.3 (3.4) | NA | NA |

| Male sex | 318 (51.5) | 322 (52.2) | NA | NA |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder | 484 (78.4) | 486 (78.8) | NA | NA |

| Acute and transient psychotic disorder | 87 (14.1) | 87 (14.1) | NA | NA |

| Psychosis not otherwise specified | 46 (7.5) | 44 (7.1) | NA | NA |

| Educational level, mean (SD), y | 10.9 (2.37) | 10.5 (2.44) | −3.186 | .001 |

| Age at onset, mean (SD), y | 20.46 (3.38) | 20.64 (3.59) | −2.746 | .006 |

| DUP, median, d | 92 | 61 | −2.588 | .01 |

| Baseline positive symptoms | 4.18 (0.72) | 4.59 (0.96) | −7.439 | <.001 |

| Baseline negative symptoms | 2.68 (1.29) | 2.68 (1.31) | −0.025 | .98 |

| Baseline affective symptoms | 2.13 (1.18) | 2.02 (1.21) | −1.936 | .05 |

| Suicide attempts during DUP | 0.13 (0.54) | 0.26 (0.74) | −3.163 | .002 |

| Premorbid occupational functioningc | ||||

| Impaired | 47 (7.6) | 48 (7.8) | 0.00 | >.99 |

| Not impaired | 570 (92.4) | 569 (92.2) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: DUP, duration of untreated psychosis; EI, early intervention; NA, not applicable; SC, standard care.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of study participants unless otherwise indicated. The EI and SC patients were individually matched based on age (±2 years), sex, and diagnosis; 548 pairs were successfully matched. For unmatched EI patients, diagnosis was matched first and then sex. Two EI patients with psychosis not otherwise specified were matched with SC patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

The z values are derived from the Wilcoxon test for paired samples; the χ2 values are derived from the McNemar test.

Impaired premorbid occupational functioning indicates unemployment or prolonged educational stagnation before the onset of illness.

Figure. Number Needed to Treat for Each Year During the 12 Study Years.

Survival Analysis

A significant association of EI with suicide survival was observed during the 12 years (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.36-0.91; P = .02) (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier plots for suicide survival are shown in the eFigure in the Supplement. The propensity score–adjusted HRs for comparing overall suicide survival between the EI and SC groups were 0.32 (95% CI, 0.14-0.73; P = .007) for year 3 or earlier and 0.87 (95% CI, 0.48-1.58; P = .65) for later than year 3 (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Propensity Score–Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Full Model for Survival.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | ||

| Standard care (control) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Early intervention | 0.57 (0.36-0.91) | .02 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.56 (0.95-2.56) | .08 |

| Female | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Age (1-y increase) | 0.99 (0.83-1.17) | .87 |

| Age at onset (1-y increase) | 1.03 (0.87-1.21) | .76 |

| Educational level (1-y increase) | 0.93 (0.85-1.01) | .10 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable.

Risk Factors for Suicide

Patients with a high number of suicide attempts during DUP and the first 3 years of the intervention were more likely to complete suicide during years 1 through 3 (Table 3). The multivariable analysis revealed that the model with these 2 variables was significant (likelihood ratio test χ2 = 20.06, P < .001) (Table 4).

Table 3. Univariate Association of Demographic and Clinical Variables With Suicide Deatha.

| Demographic | Suicide Death, HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Years 1-3 (n = 34) | Years 4-12 (n = 39) | 12 Years (n = 73) | |

| Age at onset | 0.99 (0.90-1.09) | 1.02 (0.92-1.13) | 1.01 (0.94-1.08) |

| Educational level | 0.94 (0.83-1.06) | 0.89 (0.78-1.00)b | 0.91 (0.84-0.99)b |

| Sex (reference group: female) | 1.34 (0.69-2.63) | 1.70 (0.88-3.31) | 1.52 (0.94-2.47) |

| Baseline variables | |||

| DUP, d | 1.09 (0.86-1.38) | 1.00 (0.83-1.20) | 1.04 (0.89-1.21) |

| Baseline positive symptoms | 1.03 (0.65-1.64) | 0.97 (0.70-1.35) | 1.00 (0.76-1.31) |

| Baseline negative symptoms | 0.96 (0.74-1.24) | 1.10 (0.85-1.41) | 1.03 (0.86-1.23) |

| Baseline affective symptoms | 1.11 (0.83-1.47) | 0.94 (0.70-1.28) | 1.02 (0.83-1.26) |

| Premorbid occupational impairment (reference group: not impaired) | 0.76 (0.18-3.17) | 2.69 (1.17-6.13)b | 1.72 (0.85-3.45) |

| No. of suicide attempts during DUP | 1.64 (1.24-2.17)c | 1.32 (0.89-1.96) | 1.48 (1.18-1.86)c |

| Variables of the first 3 y | |||

| No. of suicide attempts | 1.95 (1.39-2.73)c | 1.50 (0.96-2.34) | 1.72 (1.30-2.78) |

| No. of hospitalization | 1.00 (0.96-1.05) | 1.03 (0.98-1.08) | 1.02 (0.98-1.05) |

| No. of relapse | 0.95 (0.70-1.28) | 1.34 (1.03-1.75)a | 1.17 (0.95-1.43) |

| Adherence | 1.63 (0.79-3.34) | 2.55 (1.32-4.94)d | 2.11 (1.31-3.40)d |

| Presence of substance abuse (reference group: no substance abuse) | 0.56 (0.19-1.59) | 0.89 (0.28-2.80) | 0.70 (0.32-1.53) |

| Mean DDD | 0.85 (0.44-1.67) | 1.10 (0.70-1.72) | 0.98 (0.67-1.45) |

Abbreviations: DDD, defined daily dose; DUP, duration of untreated psychosis; HR, hazard ratio.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used accounting for correlated groups of observations.

P < .05.

P < .001.

P < .01.

Table 4. Multivariable Analysis of Suicidea.

| Variable | Suicide Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years 1-3 | Years 4-12 | 12 Years | ||||

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Baseline variables | ||||||

| Premorbid occupational impairmentb | NA | NA | 2.76 (1.20-6.33) | .02 | NA | NA |

| No. of suicide attempts during DUP | 1.47 (1.10-1.96) | .009 | NA | NA | 1.39 (1.08-1.74) | .009 |

| Variables during first 3 y | ||||||

| No. of suicide attempts | 1.77 (1.22-2.55) | .002 | NA | NA | 1.58 (1.17-2.14) | .003 |

| No. of relapses | NA | NA | 1.32 (1.01-1.72) | .04 | NA | NA |

| Adherence | NA | NA | 2.77 (1.32-5.80) | .007 | 2.40 (1.44-4.01) | .001 |

Abbreviations: DUP, duration of untreated psychosis; EI, early intervention; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; SC, standard care.

Backward stepwise Cox proportional hazards regression model was used accounting for correlated group of observations with adjustment for treatment group.

Reference group: not impaired.

Patients with impaired premorbid occupational functioning and a relatively high incidence of relapse and poor adherence during the first 3 years were more likely to complete suicide during years 4 through 12 (Table 3). The model was statistically significant (likelihood ratio test χ2 = 14.60, P = .006) (Table 4).

For suicide during the entire 12 years, patients with a relatively high number of suicide attempts during DUP and the first 3 years and with poor adherence during the first 3 years were significantly more likely to complete suicide during 12 years (Table 3). The model was statistically significant (likelihood ratio test χ2 = 25.56, P < .001) (Table 4).

Discussion

The results of the current study suggest that patients who underwent a 2-year EI service had significantly fewer suicides and longer survival rates during 12 years than those who did not. The main association was observed during the initial 3 years. The suicide rates of the 2 groups were similar during years 4 through 12. Jumping from height was found to be the main suicide method, similar to that of the general population in Hong Kong.36 The number of suicide attempts during the DUP and the initial 3 years were indicators of early suicide (years 1-3). Premorbid occupational impairment, number of relapses, and poor adherence during the initial 3 years of treatment were indicators of late suicide (years 4-12). Overall, patients who had more suicide attempts during DUP and the initial 3 years and had poor adherence were more likely to complete suicide during the entire 12 years.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to report the association of an EI service with the long-term suicide rate among patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders in a representative sample. Many studies15,37,38 have reported that the risk of suicide was the highest during the early stage of psychosis. The suicide rate among patients with FEP was reported to be 2.7 times higher than that among patients with chronic conditions.39 The 2-year SMR of suicide among the patients with FEP in a recent study40 was reported to be as high as 81.91. The results of our study provide evidence that patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders who received EI service had a significantly lower suicide rate than those who did not during the most vulnerable period, with the effect maintained for 12 years. Suicide is a serious global public health concern. The overall suicide rate can be reduced by almost 50% if the suicide rate among individuals with mental illness were to be reduced to the level of that in the general population.41 Because schizophrenia was found to have the second highest population-attributable risk for suicide among patients with major psychiatric conditions, the implementation of an EI service can potentially make a significant contribution to the global effort of suicide reduction. Although the SMR of the suicide rate in the EI group was almost half of that in the SC group in the current study, it was still higher than the median reported in another study.1 This finding reflects the need for further improvement of the local EI service.

In the current study, we found that a different set of risk factors contribute to suicides at different stages of illness. This finding highlights the importance of the different stages of schizophrenia as suggested in a previous study.42 A history of suicide attempts during the pretreatment and the early treatment periods was found to be a significant risk factor for early suicide (years 1-3) and suicide during 12 years but not late suicide (years 4-12). A history of suicide attempts has been consistently reported as an indicator of suicide in patients with FEP37 and chronic illness.8,9,10,11 The significance of suicide attempts during the DUP period highlights the importance of shortening the DUP.

The number of relapses and adherence during the first 3 years of treatment and premorbid occupational functioning were found to be significant indicators of suicide in the late but not the early stage. This finding agrees with the existing literature.37,43,44 The results further emphasize that these factors during the early stage of the illness could specifically affect suicide at a later stage. Although the EI services have been implemented worldwide and improve the short-term outcomes of patients with psychosis, most studies16,18,19,45 did not find a positive effect on the reduction of relapses. This finding highlights the importance of strengthening the EI service with a specific focus on relapse reduction.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study is a relatively large representative sample studied for a long period, which allowed the study of both the short- and long-term association of the EI service with suicide. Because the EI service was a regionwide service, no concurrent comparison group was possible. However, measures to ensure the compatibility of the 2 groups were implemented in participant matching and statistical analysis. The reliability of the clinical information was limited by the quality of the clinical records and was likely to be different between the SC and EI groups, which may limit the interpretation of the findings. The retrospective nature of the study precluded the determination of causality of the EI on suicide reduction. Patients who had emigrated and died abroad could not be identified in the current study. Although 1070 patients (86.7%) had clinical activities in the recent year or future clinical appointments at the time of obtaining mortality information, suggesting that patients were likely to be residing locally, the number of suicides in the current study could be underestimated. The generalizability of the results of the study may be limited by the age range of the patients in the EI service and the restriction of the diagnosis and duration of treatment of patients before entering the study.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence to support the potential association of of an EI service with reduction in suicide during a 12-year period, with the maximum association during the first 3 years. Relapse and adherence during the early stage of the illness indicated late suicide. This finding highlights the importance of the further improvement of the EI model to effectively reduce the relapse rate. Different sets of risk factors were associated with suicide at different stages of illness, suggesting the importance of phase-specific intervention.

eMethods. Sample Matching Process

eTable 1. Details of the Number of Patients Screened and Excluded With Individual Reasons of Exclusion

eTable 2. Comparison of Unweighted and Propensity Score Reweighted Patients Characteristics by Early Intervention Group (EI) and Standard Care Group (SC)

eTable 3. Details of Mortality and Suicide of Patients in Both Groups Over 12 Years

eTable 4. Propensity Score Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Early Intervention Group to Standard Care Group Before and After 3-Year (Outcome: Suicide; Other Causes of Death Are Censored)

eFigure. Kaplan-Meier Plot of the Subjects’ Survival With Outcome as Suicide

References

- 1.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(3):247-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inskip HM, Harris EC, Barraclough B. Lifetime risk of suicide for affective disorder, alcoholism and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:35-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heilä H, Haukka J, Suvisaari J, Lönnqvist J. Mortality among patients with schizophrenia and reduced psychiatric hospital care. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):725-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, et al. . Suicidal behaviour and mortality in first-episode psychosis: the OPUS trial. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s140-s146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutta R, Murray RM, Allardyce J, Jones PB, Boydell JE. Mortality in first-contact psychosis patients in the U.K. Psychol Med. 2012;42(8):1649-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuen K, Harrigan SM, Mackinnon AJ, et al. . Long-term follow-up of all-cause and unnatural death in young people with first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2014;159(1):70-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haw C, Hawton K, Sutton L, Sinclair J, Deeks J. Schizophrenia and deliberate self-harm. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35(1):50-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Deeks JJ. Schizophrenia and suicide: systematic review of risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Björkenstam C, Björkenstam E, Hjern A, Bodén R, Reutfors J. Suicide in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2014;157(1-3):1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson J, Harris MG, Harrigan SM, et al. . Suicide attempt in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2010;116(1):1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang WC, Chen ESM, Hui CLM, Chan SKW, Lee EHM, Chen EYH. Prevalence and risk factors for suicidal behavior in young people presenting with first-episode psychosis in Hong Kong. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(2):219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutta R, Murray RM, Allardyce J, Jones PB, Boydell J. Early risk factors for suicide in an epidemiological first episode psychosis cohort. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1-3):11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordentoft M, Madsen T, Fedyszyn I. Suicidal behavior and mortality in first-episode psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(5):387-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. . Comprehensive versus usual community care for first episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuipers E, Holloway F, Rabe-Hesketh S, Tennakoon L; Croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team (COAST) . An RCT of early intervention in psychosis: Croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team (COAST). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(5):358-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, et al. . A randomised multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. BMJ. 2005;331(7517):602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craig TKJ, Garety P, Power P, et al. . The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. BMJ. 2004;329(7474):1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grawe RW, Falloon IRH, Widen JH, Skogvoll E. Two years of continued early treatment for recent-onset schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(5):328-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cullberg J, Levander S, Holmqvist R, Mattsson M, Wieselgren IM. One-year outcome in first episode psychosis patients in the Swedish Parachute project. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(4):276-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen EYH, Tang JYM, Hui CLM, et al. . Three-year outcome of phase-specific early intervention for first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5(4):315-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malla A, Norman R, McLean T, Scholten D, Townsend L. A Canadian programme for early intervention in non-affective psychotic disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37(4):407-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park AL, McCrone P, Knapp M. Early intervention for first-episode psychosis: broadening the scope of economic estimates. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10(2):144-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melle I, Johannesen JO, Friis S, et al. . Early detection of the first episode of schizophrenia and suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):800-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang JYM, Wong GHY, Hui CLM, et al. . Early intervention for psychosis in Hong Kong—the EASY programme. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4(3):214-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan SKW, So HC, Hui CLM, et al. . 10-Year outcome study of an early intervention program for psychosis compared with standard care service. Psychol Med. 2015;45(6):1181-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan TC, Chang WC, Hui CL, Chan SK, Lee EH, Chen EY. Rate and predictors of disengagement from a 2-year early intervention program for psychosis in Hong Kong. Schizophr Res. 2014;153(1-3):204-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reininghaus U, Dutta R, Dazzan P, et al. . Mortality in schizophrenia and other psychoses: a 10-year follow-up of the ÆSOP first-episode cohort. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):664-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haro JM, Kamath SA, Ochoa S, et al. ; SOHO Study Group . The Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia scale: a simple instrument to measure the diversity of symptoms present in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2003;107(416):16-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nosè M, Tansella M, Thornicroft G, et al. . Is the Defined Daily Dose system a reliable tool for standardizing antipsychotic dosages? Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(5):287-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haro JM, Novick D, Bertsch J, Karagianis J, Dossenbach M, Jones PB. Cross-national clinical and functional remission rates: Worldwide Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes (W-SOHO) study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(3):194-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee EW, Wei LJ, Amato DA. Cox-type regression analysis for large number of small groups correlated failure time observations In: Klein JP, Goel P, eds. Survival Analysis: State of the Art. Amsterdam, the Netherland: Springer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao XI, Wang X, Speicher PJ, et al. . Reporting and guidelines in propensity score analysis: a systematic review of cancer and cancer surgical studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bath P, Hogg C, Tracy M, Pocock S; Optimising the Analysis of Stroke Trials Collaboration with the Writing Committee . Calculation of numbers-needed-to-treat in parallel group trials assessing ordinal outcomes. Int J Stroke. 2011;6(6):472-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yip PS, Caine E, Yousuf S, Chang SS, Wu KC, Chen YY. Means restriction for suicide prevention. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2393-2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pompili M, Serafini G, Innamorati M, et al. . Suicide risk in first episode psychosis: a selective review of the current literature. Schizophr Res. 2011;129(1):1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nordentoft M, Laursen TM, Agerbo E, Qin P, Høyer EH, Mortensen PB. Change in suicide rates for patients with schizophrenia in Denmark, 1981-97. BMJ. 2004;329(7460):261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:502-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melle I, Olav Johannesen J, Haahr UH, et al. . Causes and predictors of premature death in first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):217-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mortensen PB, Agerbo E, Erikson T, Qin P, Westergaard-Nielsen N. Psychiatric illness and risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Lancet. 2000;355(9197):9-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott J, Leboyer M, Hickie I, et al. . Clinical staging in psychiatry: a cross-cutting model of diagnosis with heuristic and practical value. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(4):243-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Hert M, McKenzie K, Peuskens J. Risk factors for suicide in young people suffering from schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;47(2-3):127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berger G, Fraser R, Carbone S, McGorry P. Emerging psychosis in young people, part 1: key issues for detection and assessment. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35(5):315-321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nordentoft M, Rasmussen JO, Melau M, Hjorthøj CR, Thorup AAE. How successful are first episode programs? a review of the evidence for specialized assertive early intervention. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(3):167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Sample Matching Process

eTable 1. Details of the Number of Patients Screened and Excluded With Individual Reasons of Exclusion

eTable 2. Comparison of Unweighted and Propensity Score Reweighted Patients Characteristics by Early Intervention Group (EI) and Standard Care Group (SC)

eTable 3. Details of Mortality and Suicide of Patients in Both Groups Over 12 Years

eTable 4. Propensity Score Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Early Intervention Group to Standard Care Group Before and After 3-Year (Outcome: Suicide; Other Causes of Death Are Censored)

eFigure. Kaplan-Meier Plot of the Subjects’ Survival With Outcome as Suicide