Key Points

Question

What are the risks and factors raised in litigation related to fillers?

Findings

Of a total of 1748 adverse events included, swelling was the most common complication followed by infections. Use of calcium hydroxyapatite and nasolabial-fold injections were each significantly associated with intra-arterial injection and necrosis; inadequate informed consent was the most common factor cited in litigation.

Meaning

Prior to injecting fillers, it is critical to have a thorough discussion of possible complications, as well as techniques to manage these complications.

Abstract

Importance

Injectable fillers are increasing in popularity as a noninvasive option to address concerns related to facial aging and volume loss. To our knowledge, there have been no large-scale analyses of adverse events and associated litigation related to filler injections.

Objectives

To determine risks of injectable fillers and analyze factors raised in litigation related to injectable fillers.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cross-sectional review, the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) manufacturer and user facility device experience (MAUDE) database was evaluated for complications from the use of the following fillers: Juvederm, Restylane, Belotero, Sculptra, Radiesse, Artefill, Bellafill, and Juvederm Voluma from 2014 to 2016. The Westlaw Next database was used to identify jury verdicts.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Complications were organized by type of filler used, location of injection, and severity. Intra-arterial injections without sequelae and those resulting in blindness or necrosis were considered severe complications. Factors raised during the litigation process were also analyzed.

Results

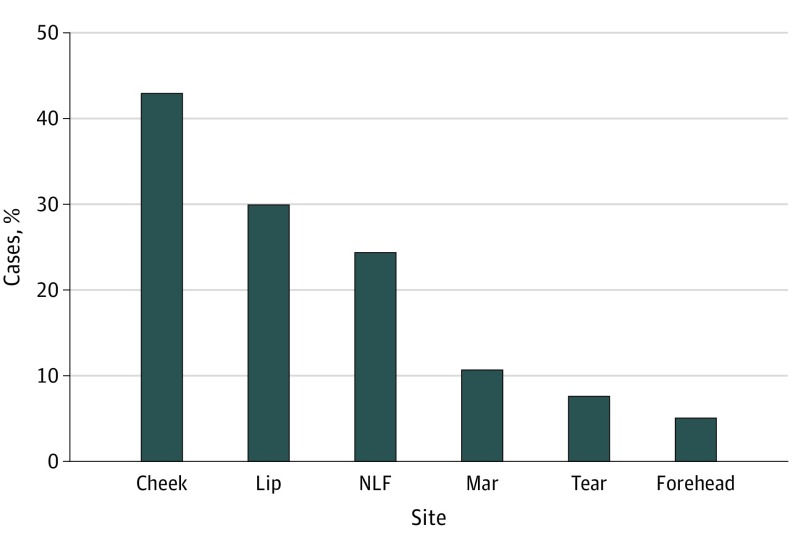

Of 1748 adverse events analyzed, most cases stemmed from cheek (751 [43.0%]) or lip (524 [30.0%]) injection. Commonly reported adverse events reported included swelling (755 [43.2%]) and infection (725 [41.5%]). Among FDA-reported complications, blindness was significantly associated with dorsal nasal injections (P < .001). Vascular compromise with and without sequela of dermal necrosis and blindness were significantly associated with Radiesse injections P < .001. Of the 9 malpractice cases identified, two-thirds involved allegations of inadequate informed consent, and the median award in cases resolved with payment was $262 000.

Conclusions and Relevance

Although specific complication profiles vary by material and injection site, common adverse events associated with injectable fillers include swelling and infection. More serious events include vascular compromise, resulting in necrosis and blindness; these events are also raised in cases involving litigation. This analysis illustrates the importance of outlining these risks in a comprehensive preoperative informed consent process.

Level of Evidence

NA.

This cross-sectional review used the US Food and Drug Administration’s manufacturer and user facility device experience database to evaluate for complications from the use of soft-tissue fillers.

Introduction

The total number of volumizing soft-tissue injectable fillers for facial rejuvenation has increased dramatically in recent years, from 650 000 in 2000 to greater than 2.4 million in 2015.1 Fillers represent an appealing modality for patients seeking to enhance their appearance, as they counteract the volume loss that occurs with age. Injections can be performed during an office visit, harbor modest costs, and are less invasive than surgical alternatives. In most cases, fillers are used without clinically significant complications to the patient, although with an increase in use and a large variability in clinician training and experience, the overall number of complications has risen.2,3,4 The true incidence of complications is difficult to ascertain because there is no universal mechanism of reporting complications, and many minor complications may not be brought to the attention of the physician.5

The cumulative effect of a complication encompasses tremendous emotional, medical, and financial impact on the patient and health care professional. Improving our understanding of filler complications is critical to minimize the medical and financial burden of these events. The paucity of large-scale analyses evaluating specific adverse events related to injectable fillers represents a critical void in the literature. In an attempt to better understand potential risks, our objectives were to examine a national resource for reported adverse events, as well as related clinical issues facilitating relevant malpractice litigation. Prior analysis of malpractice litigation related to facial plastic surgery has illustrated that perceived deficits in informed consent are commonly cited by plaintiffs pursuing litigation.6,7,8 Our hope is that this information may be used to improve both physician and patient understanding of these potential risks, as comprehensive discussion of these considerations has been shown to improve the patient-physician relationship and potentially minimize the incidence of malpractice litigation.9

Methods

This study used information from publicly available databases, and approval from the Wayne State institutional review board was not necessary.

Reportable Adverse Events

The US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA), manufacturer and user device experience (MAUDE) database was searched for adverse events stemming from the use of injectable fillers. MAUDE is a database maintained by the FDA comprising data from reports of adverse events of medical devices. The database encompasses mandatory reports from manufacturers and device user facilities, and voluntary reports from health care professionals and consumers. Its records contain information relating to the outcome of the event and any associated interventions taken. Information on the projected number of injections performed was obtained from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) survey for the years 2014, 2015, and 2016.

The MAUDE database was queried for complications related to the injection of Restylane (hyaluronic acid filler gel; Galderma), Juvederm and Juvederm Voluma (hyaluronic acid filler; Allergan), Belotero (hyaluronic acid; Merz Pharmaceuticals), Sculptra (poly-L-lactic acid; Sanofi), Radiesse (calcium hydroxylapatite; Merz Pharmaceuticals), and Artefill/Bellafill (polymethylmethacrylate; Suneva) from January 1, 2014, until December 31, 2016.10,11,12,13,14

Medical Malpractice Litigation

The Westlaw Next Database (Thomson Reuters) was used to search for malpractice litigation stemming from the use of soft-tissue fillers in the face. This resource encompasses publicly available court records and has been invaluable in myriad analyses examining malpractice litigation in topics relevant to numerous specialties.15,16,17,18,19,20 Specifically, the advanced search function was used to search for jury verdicts and settlements related to “medical malpractice” in combination with the following search terms: Juvederm or Voluma or Belotero or Restylane or Kybella or Hyaluronic or hydroxyapatite or fillers or injectables or injectable or Radiesse or Sculptra or collagen or Zyderm or Zyplast or rejuvenation or rejuvenate or silicone. Of the 48 initial search results, 39 were excluded because they were not relevant to this topic (ie, these terms were mentioned incidentally or were not the focus of litigation). Each verdict and settlement report was thoroughly examined for defendant specialty, outcome, award, and other factors raised in proceedings.

Statistical Analysis

The data were collected and analyzed using Microsoft Excel. χ2 Testing was used to analyze complications by filler and location. The threshold for significance was set at P < .05. Minitab software (Minitab Inc) and Microsoft Excel (2009) were used for data analysis.

Results

Adverse Events and Management

There were 1748 reported adverse events involving patient injury from January 1, 2014, until December 31, 2016. Based on ASPS statistics, there were 754 772 injections of Radiesse, 5.75 million injections involving hyaluronic acid (HA), 389 604 injections of Sculptra, and 52 740 injections of Artefill and Bellafill during this time frame.21,22,23 Forty-eight percent of complications (839) were related to the use of Juvederm Voluma, and 36.2% (633) were from Juvederm. Restylane encompassed 7.3% (128) reported adverse events, and Radiesse, a calcium hydroxyapatite–based filler, was used in 96 reported complications (5.5%). Sculptra was used in 47 (2.7%) and Belotero in 5 (0.3%). No deaths were reported.

The most common complications recorded were swelling, infection, the presence of a nodule, and pain in 755 (43.2%), 725 (41.5%), 509 (29.1%), and 420 (24.0%) of complications reported, respectively; 296 patients (39.2%) with swelling were treated with antibiotics, and 76 (10.4%) were treated with hyaluronidase. Of the 420 patients (24.1%) who complained of excessive pain, 40 (9.5%) were treated with hyaluronidase and 179 (42.7%) were treated with antibiotics. Of the 45 patients (2.6%) who had excessive blanching of the skin, 9 (20.0%) were treated with hyaluronidase.

Complications by Location

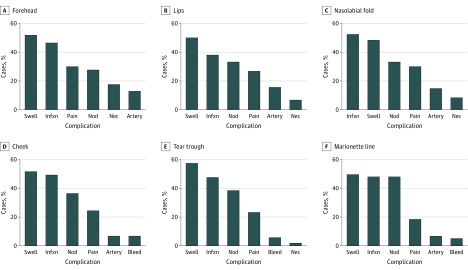

The reported complication rates of injections to the forehead, nasolabial fold, lips, cheek, marionette lines, and tear troughs were analyzed. The cheeks represented the most common site of complications in 751 patients (43.0%) (Figure 1). For all locations except the nasolabial folds, swelling was the most common complication reported, with a range of 95 reported cases in the marionette lines (50.3%) to 79 in the tear troughs (57.7%). Infection was the most commonly reported complication in the nasolabial folds (227 [53.0%] of reported complications). Infection was the second most common complication for the 5 other locations analyzed (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Location of Reported Adverse Events.

Mar indicates marionette line; NLF, nasolabial fold; tear, tear trough.

Figure 2. Complications Reported by Injection Site.

Artery indicates arterial embolization; bleed, excessive bleeding requiring intervention; blind, blindness resulting from the injection; infxn, infection; nec, necrosis; nod, nodule; swell, swelling.

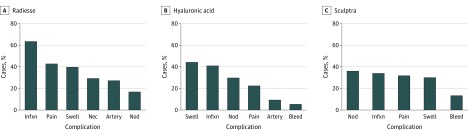

Complications by Filler

For the purpose of this analysis, the complications of the HA-based fillers, Restylane, Belotero, Juvederm, and Juvederm Voluma were combined. For the HA fillers, swelling, followed by infection, was the most commonly reported complication in 703 (43.8%) and 649 (40.4%), respectively. These complications comprised 0.01% of all injections for HA fillers. For Radiesse, the most common complication reported was infection in 61 (63.5%), followed by pain in 41 (42.7%). These complications were reported in 0.008% and 0.007% of Radiesse injections, respectively. For Sculptra, nodule formation was the most common complication reported in 17 (36.1%) (Figure 3). This comprised 0.004% of all Sculptra injections. For Artefill/Bellafill nodule formation was the most commonly reported complication in 5 (40.0%), and this comprised 0.01% of all Artefill/Bellafill injections performed. Nodule formation was significantly associated with Sculptra injections at P = .01. Swelling was significantly more likely to be associated with HA injections at P = .001.

Figure 3. Complications by Filler.

Artery indicates arterial embolization; bleed, excessive bleeding requiring intervention; infxn, infection; nec, necrosis; nod, nodule; swell, swelling. (Radiesse [calcium hydroxylapatite], Merz Pharmaceuticals; Sculptra [poly-L-lactic acid], Sanofi.)

Severe Complications

Severe complications included intra-arterial injections without sequelae, intra-arterial injection with vascular compromise resulting in necrosis, and intra-arterial injection with distant sequelae resulting in blindness. Intra-arterial injection without sequelae was significantly more likely to be a reported complication of injections at the lip and nasolabial fold (P < .001) (Table 1). In addition, lip and nasolabial-fold injections were most likely to result in necrosis in 35 (6.7%) and 36 (8.4%), respectively (P < .001), and use of Radiesse was significantly more likely to result in intra-arterial injection and intra-arterial injection with necrosis (P < .001). Eight injections resulted in blindness. Blindness was significantly more likely to be a reported complication of Radiesse (P < .001) and of dorsal nasal injections, comprising 1 (16.7%) of nasal injection complications (P < .001). In total, 0.003% of Radiesse injections (22) resulted in necrosis and 0.0001% (1) resulted in blindness. There was 1 report of anaphylaxis following Bellafill injection to the dorsal aspect of the nose. The patient was treated with steroids and antihistamines and transferred to a hospital and stabilized. This was the patient’s second Bellafill injection, and the patient had a bovine collagen skin test performed prior to the first injection.

Table 1. In-depth Analysis of Serious Complications of Filler Injections.

| Location and Type of Filler | No. (%)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial Only | Blindness | Necrosis | Total No. of Injections | |

| Location | ||||

| Lip | 81 (15.4) | 0 | 35 (6.7) | 525 |

| Nasolabial fold | 63 (14.7) | 0 | 36 (8.4) | 428 |

| Cheek | 51 (6.8) | 0 | 3.2 (24) | 751 |

| Marionette line | 13 (6.9) | 0 | 7 (3.7) | 189 |

| Periorbital | 0 | 4 (2.9) | 3 (2.2) | 137 |

| Forehead | 12 (13.3) | 3 (3.3) | 16 (17.7) | 90 |

| Dorsal aspect of nose | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 6 |

| Fillerb | ||||

| Hyaluronic acid | 151 (9.4) | 7 (0.4) | 136 (8.5) | 1605 |

| Sculptra | 4 (8.5) | 0 | 2 (4.3) | 47 |

| Radiesse | 27 (28.1) | 1.0 (1.0) | 29 (30.2) | 96 |

Percentages indicate the fraction in that specific location or for that specific filler only. P < .001 for all comparisons.

Sculptra (poly-L-lactic acid), Sanofi; Radiesse (calcium hydroxylapatite), Merz Pharmaceuticals).

Litigation

A search of the West Law Next database yielded 9 cases. Five were resolved in the defendant’s favor. Of the cases resulting in a monetary payment, the mean amount awarded was $242 000. Six cases involved allegedly inadequate informed consent, and 5 of 9 cases involved patients sustaining allegedly permanent injury. In 5 cases, plaintiffs alleged that the filler choice or decision to proceed with injection was not appropriate/contraindicated. Two cases involved an arterial injection, while 1 patient experienced blindness following an injection to the temporalis region (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of the Cases Litigated Related to Facial Fillers.

| Age, y/Sex | Outcome | Awarda | Defendant | Filler | Location | IP | IC | Perm | Alleged Complication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42/F | Defendant | NA | FPRS | Fibrin (autologous) | Lips, NLF | Y | AL | Y | Plaintiff claimed pain and scarring in region |

| 48/F | Settlement | 425 | Plastic | Juvedermb | Temporalis | Y | Y | Y | Juvederm embolized retinal artery resulting in blindness |

| U/F | Plaintiff | 349 | Esthetician | Foreign pro | Periorbital | N | N | AL | Pain, scarring, and disfiguration in injection distribution |

| U/F | Settlement | 175 | Physician, nurse | Collagen | Glabella | Y | N | Y | Supratrochlear injection resulting in pain and necrosis |

| U/F | Defendant | NA | Dermatologist | Evolence | Face unspecified | N | N | AL | Temporary facial nerve paralysis |

| U/F | Defendant | NA | Plastic | CaHa | Cheek | Y | N | Y | Pain and paresthesia |

| U/F | Plaintiff | 21 | Otolaryngologist | Silicone | Periorbital | N | N | AL | Postinjection swelling |

| 46/F | Defendant | NA | Dermatologist | Collagen | Cheek | Y | Y | Y | HSV outbreak |

| 60/F | Defendant | NA | Plastic | Collagen | Face unspecified | N | Y | Y | Postinjection bleeding and scarring |

Abbreviations: AL, alleged lack of informed consent; CaHa: calcium hydroxyapatite; FPRS: facial plastic and reconstructive surgery; foreign pro, unapproved foreign product that was not specified; HSV, herpes simplex virus; IC, presence of informed consent; IP, intraprocedural; NA, not applicable; NLF, nasolabial fold; perm, permanent damage; plastic, plastic surgery; U, unknown; Y, yes; N, no.

Awards are given in thousands of US dollars.

Juvederm (hyaluronic acid filler); Allergan.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the most expansive analysis of filler complications in the literature. The value of the present study lies in our analysis of a large number of complications contrasting various modalities of soft-tissue injectable fillers. With these considerations in mind, discussion of reported adverse events may improve the patient education process and should certainly be included in any preprocedural discussion. In addition to representation in a significant proportion of reported adverse events, complaints such as swelling, infection, and blindness have also been raised in litigation (Table 2). Interestingly, inadequate informed consent was noted to be present in greater than half of cases progressing far enough to inclusion in publicly available court records.

Choice of Filler

An ever-expanding array of volumizing injectable fillers with a diversity of mechanism of action and composition are available to the aesthetic practitioner. The 4 main categories of fillers include the calcium hydroxyapatite-based Radiesse, the poly-L-lactic acid agent Sculptra, the collagen-based filler with polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) crystals Bellafill and HA-based fillers. Radiesse is an injectable implant composed primarily of calcium hydroxyapatite. It is FDA approved for subdermal implantation and enhancement of moderate to deep facial wrinkles, such as the nasolabial folds.24 Its duration of action is 12 to 18 months, and it has a high G′ (elastic modulus) and viscosity prohibiting flashback during injection.

Sculptra is an injectable poly-L-lactic acid implant in the form of a lyophilized cake that is indicated for restoration of lipoatrophy in patients receiving treatment for human immunodeficiency virus and in correction of shallow to deep nasolabial folds.25 Sculptra causes gradual volume restoration by stimulating neocollagen formation and can take up to 6 months to show full effect.26 Bellafill (formerly branded as Artefill) is a filler composed of 80% purified bovine collagen and 20% PMMA microspheres.27 The microspheres remain in place following the injection and stimulate the body to produce its own collagen; 30 days prior to the first injection, patients are required have a skin allergy test for sensitivity to bovine collagen.

The largest category of fillers encompasses those that are derived from various formulations of HA, a naturally occurring glycosaminoglycan that is a main component of extracellular matrix.28 The lower viscosity of this filler makes it an ideal choice for enhancing fine lines and molding. In addition, this property allows withdrawal of material during injection, facilitating identification of intravascular injection. The effects of hyaluronic acid fillers are also able to be reversed with a subsequent injection of hyaluronidase.29

Complications by Filler Type

Our results revealed a significant difference in complications based on type of filler used. Nodule formation was significantly associated with Sculptra (P = .01) (Figure 3). Other studies on poly-L-lactic acid fillers have noted nodules to be the most common long-term complication, with an onset of 7 months following injection and resolution usually within 24 months.3,5,30,31,32 Nodule formation can be prevented by instructing the patient to massage the area, 5 times a day for 5 minutes for 5 days.25 Reconstitution guidelines are also evolving, and the current recommendation is to reconstitute the drug at least 2 hours prior to injection.33 Persistent nodules are treated either with steroid injections or attempts to break up the nodule using a needle.

Hyaluronic acid–based fillers are the most common injectable fillers used. Of the 4 HA-based fillers analyzed, infection and swelling were the most commonly reported complications (Figure 3). The HA-based fillers had the highest rate of infections out of all the fillers studied, but this did not reach statistical significance. It is important to note that infections were reported in the event description, and there are no clear guidelines as to what defines an infection. Other studies that sampled a smaller population found that swelling and erythema were the common sequela of filler injections.34 Therefore, this raises the possibility that patients presenting with erythema or tenderness were prematurely diagnosed as having an infection and aggressively treated with antibiotics, despite them not having significant clinical features associated with an infection. Prior studies also suggest that the type of filler used is not associated with infection risk, and that complications may be more related to technical faults and breaks in sterile technique.2,24,35,36,37 Infections generally result from natural skin flora, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, being introduced through the injection site.38 These infections often respond to oral antibiotics.39 In addition, there are reports of filler materials supporting bacterial biofilm growth, resulting in chronic inflammation and a foreign-body reaction. Multiple needle passes through a biofilm-contaminated surface, resulted in a 10 000 factor increase in risk of contamination of filler material.40

Swelling can be secondary to a local inflammatory response to foreign material or superficial placement of the filler. Studies have shown that using a blunt-tip cannula instead of a hypodermic syringe produces less edema.41 For persistent swelling, suggested treatments include hyaluronidase and intralesional steroid injections.5 These are largely “early” complications of filler injections, presenting in a matter of days.35

Serious Complications

We further evaluated the characteristics of patients who had serious complications, including intra-arterial injection without sequela, intra-arterial injection with subsequent skin necrosis, and blindness following intra-arterial injection. Of the cases analyzed, lip, forehead, and nasolabial-fold injections were significantly more likely to result in intra-arterial injection. Intra-arterial injection was diagnosed based on findings from the reporting clinician. Findings, which suggested intra-arterial injection without sequela, included blanching at time of injection and skin duskiness without necrosis. Reported injections into the cheek, nasolabial fold, and forehead were significantly associated with skin necrosis. In addition, Radiesse was significantly more likely to result in intra-arterial complications, skin necrosis, and blindness based on the reported filler complications. Necrosis can be either secondary to intra-arterial injection, leading to vascular occlusion, or necrosis secondary to pressure from the filler compressing venous tributaries and resulting in stasis of blood flow.42

Blindness is another serious complication of intravascular injection of fillers. Dorsal nasal injections were significantly associated with blindness. The dorsal nasal artery is a terminal branch of the ophthalmic artery, and inadvertent injection of this vessel can result in blindness. The filler travels in a retrograde manner until it reaches the branching point of the ophthalmic artery, where it is then carried forward and lodges at the branching point of the artery.43

Injection of filler in the vicinity of named vessels, such as the angular artery or supratrochlear artery, results in the increased risk of vascular compromise. In many instances, needle aspiration may not demonstrate any flashback blood; hence, a thorough knowledge of arterial anatomy is necessary prior to injection.44 Moreover, the increased propensity of Radiesse to cause vascular compromise could be related to particle size, with larger particles resulting in more proximal vessel obstruction. In addition, certain particles may have an increased ability to stimulate the clotting cascade, ultimately resulting in skin necrosis.45,46 Intraprocedural diagnosis of an intravascular injection is very challenging with Radiesse, secondary to the high viscosity and opaque color preventing flashback during the injection process.38 The rich vascular cascade of the face also means that sites distant to the injection site can be damaged.47 Occlusion of the ophthalmic artery is a devastating consequence with no good therapy, often resulting in irreversible blindness.48

Litigation and Facial Fillers

In our contemporary health care environment, characterized by an increasing propensity for patients to consider litigation, it is critical to understand factors raised in malpractice cases. Other studies analyzing litigation in plastic surgery have listed allegations regarding a practitioner’s lack of expertise, lack of informed consent, and poor cosmetic outcome as factors cited in litigation.7,49 Alleged inadequate informed consent was cited as a factor of litigation in two-thirds of cases analyzed. Half of the cases involving a lack of informed consent were resolved with a financial reward for the plaintiff. Currently, a large fraction of filler injections occur in a medical spa setting, by non–health care professionals, and sometimes are performed without written informed consent. Improved online patient education material and thorough preprocedural discussions with patients with specific attention to complications, is critical so that patients understand the risks of the procedure they are undertaking.50

Limitations

There are several limitations of the MAUDE database. It is a passive surveillance database and hence can suffer from underreporting, especially in FDA off-label areas. In addition, some of the data can be biased or incomplete. Moreover, the data for total number of injections were obtained from the ASPS yearly reports, which are based on information from surveys that are then extrapolated to produce total injection numbers. Furthermore, there are no strict criteria used to define clinical entities, such as infection, and accurate diagnosis of the complication is dependent on reporting by health care professionals. Even consumers can file reports. Despite these limitations, the MAUDE database is useful for analyzing the relative proportion of complications and comparing the reported complication profile of different fillers. Westlaw Next encompasses publicly available jury verdicts and settlement reports. Numerous cases that are settled never make it to the database. While it cannot estimate the incidence of litigation, it is important in revealing factors raised in litigation and their association with litigation outcomes.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study is the most wide-scale analysis of reported complications of filler injections. Although swelling and infection were the most commonly reported events, of the serious complications reported to the FDA, Radiesse was significantly more likely to result in vascular compromise, and injections to the nasal dorsum were significantly associated with blindness. Injectors need to have thorough knowledge of filler complications and their appropriate management. An analysis of litigation surrounding fillers demonstrated that alleged deficiencies of informed consent were a commonly cited factor. Improved communication with patients may enhance their understanding of the procedure and potentially reduce litigation.

References

- 1.American Society of Plastic Surgeons , 2014. Plastic surgery statistics report. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics?sub=2014+Plastic+Surgery+Statistics. Accessed June 1, 2017.

- 2.Haneke E. Managing complications of fillers: rare and not-so-rare. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8(4):198-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duracinsky M, Leclercq P, Herrmann S, et al. . Safety of poly-L-lactic acid (New-Fill®) in the treatment of facial lipoatrophy: a large observational study among HIV-positive patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodward J, Khan T, Martin J. Facial filler complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2015;23(4):447-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemperle G, Rullan PP, Gauthier-Hazan N. Avoiding and treating dermal filler complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3)(suppl):92S-107S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svider PF, Carron MA, Zuliani GF, Eloy JA, Setzen M, Folbe AJ. Lasers and losers in the eyes of the law: liability for head and neck procedures. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014;16(4):277-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kandinov A, Mutchnick S, Nangia V, et al. . Analysis of factors associated with rhytidectomy malpractice litigation cases. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19(4):255-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sykes JM. is studying rhytidectomy malpractice cases enough to understand why patients are dissatisfied? more patient communication, less malpractice litigation. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19(4):259-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. . Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024-2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alemzadeh H, Raman J, Leveson N, Kalbarczyk Z, Iyer RK. Adverse events in robotic surgery: a retrospective study of 14 years of FDA data. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0151470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connor MJ, Marshall DC, Moiseenko V, et al. . Adverse events involving radiation oncology medical devices: comprehensive analysis of US Food and Drug Administration data, 1991 to 2015. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97(1):18-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez J, Soni A, Calva D, Susarla SM, Jallo GI, Redett R. Iatrogenic surgical microscope skin burns: a systematic review of the literature and case report. Burns. 2016;42(4):e74-e80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omar A, Pendyala LK, Ormiston JA, Waksman R. Review: stent fracture in the drug-eluting stent era. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17(6):404-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tambyraja RR, Gutman MA, Megerian CA. Cochlear implant complications: utility of federal database in systematic analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131(3):245-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rayess HM, Gupta A, Svider PF, et al. . A critical analysis of melanoma malpractice litigation: should we biopsy everything? Laryngoscope. 2017;127(1):134-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singer MC, Iverson KC, Terris DJ. Thyroidectomy-related malpractice claims. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(3):358-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svider PF, Blake DM, Sahni KP, et al. . Meningitis and legal liability: an otolaryngology perspective. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35(2):198-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Svider PF, Blake DM, Husain Q, et al. . In the eyes of the law: malpractice litigation in oculoplastic surgery. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(2):119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svider PF, Eloy JA, Folbe AJ, Carron MA, Zuliani GF, Shkoukani MA. Craniofacial surgery and adverse outcomes: an inquiry into medical negligence. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124(7):515-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovalerchik O, Mady LJ, Svider PF, et al. . Physician accountability in iatrogenic cerebrospinal fluid leak litigation. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(9):722-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ASPS National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery Procedural Statistics 2016. Plastic Surgery Statistics. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2016/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2016. Accessed June 1, 2017.

- 22.Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. 2014 Plastic Surgery Statistics. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics?sub=2014+Plastic+Surgery+Statistics. Accessed June 1, 2017.

- 23.Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. 2015 Plastic Surgery Statistics. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics?sub=2015+Plastic+Surgery+Statistics. Accessed June 1, 2017.

- 24.Bass LS, Smith S, Busso M, McClaren M. Calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse) for treatment of nasolabial folds: long-term safety and efficacy results. Aesthet Surg J. 2010;30(2):235-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgess CM, Quiroga RM. Assessment of the safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid for the treatment of HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(2):233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgess CM, Lowe NJ. NewFill for skin augmentation: a new filler or failure? Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(12):1530-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellafill® for acne scars and nasolabial folds. Instructional Videos. Bellafill Instructions for Use. https://www.bellafill.com/for-physicians/resources/instructional-videos/. Accessed June 3, 2017.

- 28.Klein AW, Elson ML. The history of substances for soft tissue augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26(12):1096-1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert E, Hui A, Waldorf HA. The basic science of dermal fillers: past and present, part I: background and mechanisms of action. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(9):1059-1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledon JA, Savas JA, Yang S, Franca K, Camacho I, Nouri K. Inflammatory nodules following soft tissue filler use: a review of causative agents, pathology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14(5):401-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keni SP, Sidle DM. Sculptra (injectable poly-L-lactic acid). Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2007;15(1):91-97, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldman MP. Cosmetic use of poly-L-lactic acid: my technique for success and minimizing complications. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(5):688-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sculpta Aesthetic (injectable poly-L-lactic acid). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf3/P030050S002c.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2017.

- 34.Sadick NS, Katz BE, Roy D. A multicenter, 47-month study of safety and efficacy of calcium hydroxylapatite for soft tissue augmentation of nasolabial folds and other areas of the face. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(suppl 2):S122-S126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colbert SD, Southorn BJ, Brennan PA, Ilankovan V. Perils of dermal fillers. Br Dent J. 2013;214(7):339-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grippaudo FR, Pacilio M, Di Girolamo M, Dierckx RA, Signore A. Radiolabelled white blood cell scintigraphy in the work-up of dermal filler complications. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40(3):418-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emer J, Sundaram H. Aesthetic applications of calcium hydroxylapatite volumizing filler: an evidence-based review and discussion of current concepts (part 1 of 2). J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(12):1345-1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilbert E, Hui A, Meehan S, Waldorf HA. The basic science of dermal fillers: past and present, part II: adverse effects. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(9):1069-1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saththianathan M, Johani K, Taylor A, et al. . The role of bacterial biofilm in adverse soft-tissue filler reactions: a combined laboratory and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(3):613-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fulton J, Caperton C, Weinkle S, Dewandre L. Filler injections with the blunt-tip microcannula. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(9):1098-1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cox SE, Adigun CG. Complications of injectable fillers and neurotoxins. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24(6):524-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCleve DE, Goldstein JC. Blindness secondary to injections in the nose, mouth, and face: cause and prevention. Ear Nose Throat J. 1995;74(3):182-188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeLorenzi C. Complications of injectable fillers, part 2: vascular complications. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34(4):584-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barbucci R, Lamponi S, Magnani A, et al. . Influence of sulfation on platelet aggregation and activation with differentially sulfated hyaluronic acids. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1998;6(2):109-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Braverman IM, Keh-Yen A. Ultrastructure of the human dermal microcirculation, IV: valve-containing collecting veins at the dermal-subcutaneous junction. J Invest Dermatol. 1983;81(5):438-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue K, Sato K, Matsumoto D, Gonda K, Yoshimura K. Arterial embolization and skin necrosis of the nasal ala following injection of dermal fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(3):127e-128e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silva MTT, Curi AL. Blindness and total ophthalmoplegia after aesthetic polymethylmethacrylate injection: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62(3B):873-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mehta S, Farhadi J, Atrey A. A review of litigation in plastic surgery in England: lessons learned. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(10):1747-1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rayess H, Zuliani GF, Gupta A, et al. . Critical analysis of the quality, readability, and technical aspects of online information provided for neck-lifts. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19(2):115-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]