Key Points

Question

Does the treatment of the buccinator muscle with botulinum toxin in the setting of facial synkinesis improve patient symptoms?

Findings

In this prospective cohort study, buccinator treatment did not change Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire scores relative to no-buccinator treatment cycles. However, subanalysis of questions relevant to buccinator function (facial tightness and lip movement), did show significant improvement with the addition of buccinator treatment.

Meaning

The treatment of the buccinator muscle with botulinum toxin in well-selected patients with facial synkinesis can yield significant symptom benefit.

This cohort study evaluates outcomes for patients treated with botulinum toxin applied to the buccinator muscle in the setting of facial synkinesis.

Abstract

Importance

The buccinator, despite being a prominent midface muscle, has been previously overlooked as a target in the treatment of facial synkinesis with botulinum toxin.

Objective

To evaluate outcomes of patients treated with botulinum toxin to the buccinator muscle in the setting of facial synkinesis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospective cohort study of patients who underwent treatment for facial synkinesis with botulinum toxin over multiple treatment cycles during a 1-year period was carried out in a tertiary referral center.

Interventions

Botulinum toxin treatment of facial musculature, including treatment cycles with and without buccinator injections.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Subjective outcomes were evaluated using the Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ) prior to injection of botulinum toxin and 2 weeks after treatment. Outcomes of SAQ preinjection and postinjection scores were compared in patients who had at least 1 treatment cycle with and without buccinator injections. Subanalysis was performed on SAQ questions specific to buccinator function (facial tightness and lip movement).

Results

Of 84 patients who received botulinum toxin injections for facial synkinesis, 33 received injections into the buccinator muscle. Of the 33, 23 met inclusion criteria (19 [82.6%] women; mean [SD] age, 46 [10] years). These patients presented for 82 treatment visits, of which 44 (53.6%) involved buccinator injections and 38 (46.4%) were without buccinator injections. The most common etiology of facial paralysis included vestibular schwannoma (10 [43.5%] participants) and Bell Palsy (9 [39.1%] participants). All patients had improved posttreatment SAQ scores compared with prebotulinum scores regardless of buccinator treatment. Compared with treatment cycles in which the buccinator was not addressed, buccinator injections resulted in lower total postinjection SAQ scores (45.9; 95% CI, 38.8-46.8; vs 42.8; 95% CI, 41.3-50.4; P = .43) and greater differences in prebotox and postbotox injection outcomes (18; 95% CI, 16.2-21.8; vs 19; 95% CI, 14.2-21.8; P = .73). Subanalysis of buccinator-specific scores revealed significantly improved postbotox injection scores with the addition of buccinator injections (5.7; 95% CI, 5.0-6.4; vs 4.1; 95% CI, 3.7-4.6; P = .004) and this corresponded to greater differences between prebotulinum and postbotulinum injection scores (3.3; 95% CI, 2.7-3.9; vs 2.0; 95% CI, 1.4-2.6; P = .02). The duration of botulinum toxin effect was similar both with and without buccinator treatment (66.8; 95% CI, 61.7-69.6; vs 65.7; 95% CI, 62.5-71.1; P = .72).

Conclusions and Relevance

The buccinator is a symptomatic muscle in the facial synkinesis population. Treatment with botulinum toxin is safe, effective and significantly improves patient symptoms.

Level of Evidence

3.

Introduction

Synkinesis of the facial mimetic musculature is a common sequela following facial weakness. Coinnervation of facial musculature by misdirected axonal sprouting after a proximal nerve injury results in static and dynamic hypertonicity and aberrancy, which can have profound functional and psychological consequences.1,2,3 Patient morbidity is variable, and symptoms range from mild sensation of midfacial tightness to significant pain, limited mimetic expression, reduced visibility, cheek biting, and difficulty eating. The typical treatment of synkinesis consists of a combination of neuromuscular retraining with physical therapy and targeted botulinum toxin (BT) injections.4,5 The latter has become an integral part of outpatient treatment of patients with facial synkinesis and yields objective and subjective improvement in facial function, including decreased facial asymmetry, reduced involuntary muscle contractions, and improved quality of life.6,7,8,9,10

Appropriately targeting synkinetic muscles responsible for a patient’s primary symptoms is imperative, and a variety of muscles in the face have been previously injected with good results for patient outcomes.1,3,4,9,10,11,12 The most common pattern of facial synkinesis is ocularoral synkinesis, and therefore therapy has been targeted at the associated superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS)-invested mimetic musculature.13,14 The buccinator, despite having a considerable role in lateral excursion of the commissure of the mouth and flattening the buccal mucosa against the teeth during mastication, is commonly overlooked in the treatment of facial synkinesis.4 A recent report demonstrated the possible role of BT injections to the buccinator in treating synkinesis and found that there was improvement in validated Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ) scores in patients receiving buccinator injections.14 The buccinator was not evaluated outside of the population's standard injection regimen, a limitation of the study cited by the authors. The goal of this study was therefore to compare the outcomes of patients with facial synkinesis at our institution treated with and without buccinator injections to elucidate the potential benefit of this intervention.

Methods

Study Design

Vanderbilt University institutional review board approval to perform a prospective cohort study on patients with facial synkinesis was obtained. All patients treated for facial synkinesis at the Vanderbilt Bill Wilkerson Pi Beta Phi Rehabilitation Institute and Department of Otolaryngology (Nashville, TN) over the course of a 1-year period were considered for inclusion (February 2016-February 2017). Participants were not compensated. After written informed consent was obtained, patients were injected with onabotulinumtoxin A injections (BT, Allergan) using an EMG-guided needle and completed the SAQ on the day of their treatment.15 The same questionnaire was sent via email to patients through the Vanderbilt RedCap secure web application 2 weeks after their BT injection to determine posttreatment severity of synkinesis symptoms. At 2 weeks, patients would be expected to have their maximal treatment benefit given the pharmacodynamic properties of BT. Because data were collected over the course of a 12-month period with interval injections occurring every 3 months, each patient may have completed up to 4 pretreatment and 4 posttreatment SAQ questionnaires. In the event that multiple surveys were completed by the same patient for a given condition (with or without buccinator treatment), the average of the patient’s survey scores were used.

For comparative purposes, patients were included only if they (1) completed pretreatment and posttreatment surveys for the same treatment cycle without a buccinator injection and (2) completed pretreatment and posttreatment surveys for the same treatment cycle after a buccinator injection. As such, in this crossover study a patient’s outcomes with buccinator injections were compared with his or her own outcomes without a buccinator injection. Demographic information, etiology of facial paralysis, and treatment history were collected retrospectively. Pretreatment SAQ scores, posttreatment SAQ scores, and differences between these scores were compared with and without buccinator injection. The SAQ is a 9-item, patient-graded instrument of questions evaluating several muscle groups including the periocular, midface, perioral, and neck muscles. Therefore, to better isolate the effect of the buccinator injections, scores from survey question 5 (“when I close my eyes, my face gets tight”) and question 6 (“when I close my eyes, the corner of my mouth moves”) were isolated and a subgroup analysis was performed on these combined questions (referred to as buccinator-specific questions). To account for variability in pre-BT and post-BT scores among patients, the absolute difference in mean pre-BT and post-BT scores were also calculated. The duration of BT effect is a subjectively reported measure collected from patients at each visit in reference to their prior injection.

Indications for Buccinator Treatment

Patients were offered injections to the buccinator if they reported a persistent sensation of tightness at the oral commissure despite adequate treatment of other muscles, distortion or retraction of the oral commissure, difficulty controlling a food bolus with chewing, or frequent biting of the cheek during chewing. Patients were also offered treatment of the buccinator if they plateaued on their current injection target regimen and were interested in possible improvement with a new target muscle. Patient selection was guided with the help of a physical therapist specializing in facial rehabilitation.

Procedure: Botox Injection

A topical anesthetic containing 20% benzocaine, 6% lidocaine, and 4% tetracaine was applied to facial injection sites and a 20% benzocaine oral anesthetic (Hurricaine, Beutlich Pharmaceuticals) was applied to the buccal mucosa. Injections were performed with a 1.5-inch×27-gauge disposable hypodermic needle electrode with a luer lock hub and a 4 U/0.1 mL BT dilution. Buccinator injections were performed beneath the dentate line in the buccal mucosa below and anterior to the level of Stenson’s duct (Figure). The needle was passed perpendicularly through the mucosa at this landmark. The Nicolet VikingQuest Portable electromyography (EMG) system (Natus Neurology, Inc) was used to monitor the presence of muscle hyperactivity on insertion and with voluntary movement of the targeted muscle and synkinetic muscles in the oralocular pattern. In regards to the buccinator, we found it helpful to ask the patients to relax their mouth once the needle was in place to avoid any active muscle tension during EMG monitoring. The patient was then asked to close his or her eyes. True synkinesis results in an increase in the EMG signal. A single bolus of BT is then placed into the muscle belly. Dosing was typically started at or less than 2.5 U because this is a similar starting dose for other midface muscles (ie, rizorius) at our center.

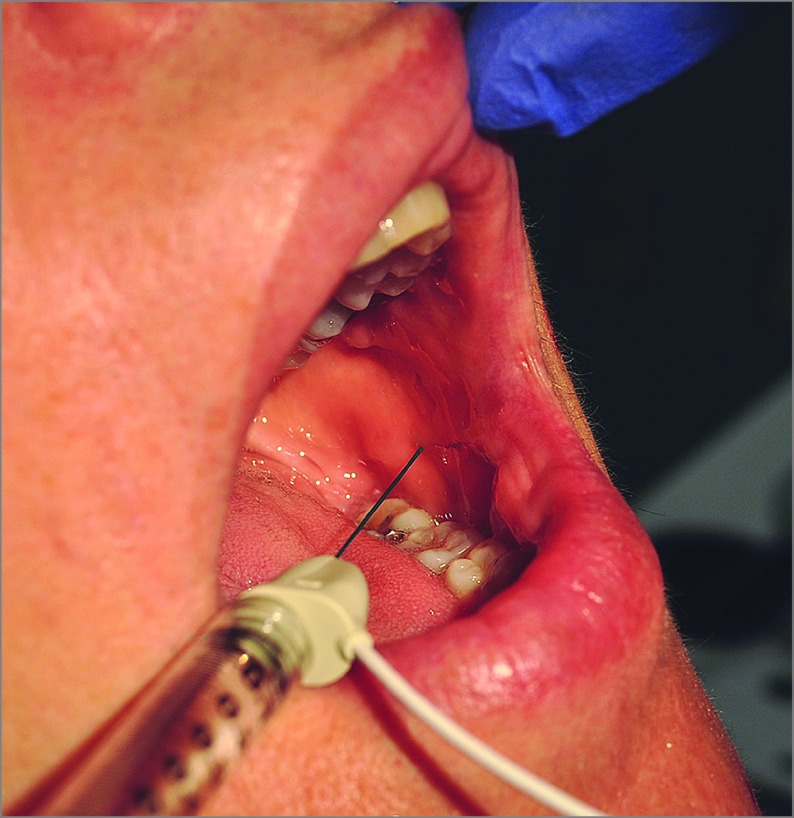

Figure. Demonstration of Botulinum Toxin Injection Into the Buccinator Muscle.

Buccinator injections are performed beneath the dentate line in the buccal mucosa below and anterior to the level of Stenson’s duct. An EMG is used to monitor presence of muscle hyperactivity on insertion and with voluntary movement of the targeted muscle prior to administration of botulinum toxin.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS statistical analysis software (version 22.0, IMB Corp). Descriptive statistics for quantitative variables were computed as mean with standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables are expressed as counts and percents. Significance of the differences between treatment outcomes (SAQ scores) with and without buccinator injections were determined using 2-tailed t tests (paired or unpaired where appropriate) or ANOVA. Differences with P ≤ .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 84 patients received BT injections for facial synkinesis during the 12-month treatment period, of which 33 received injections into the buccinator. Of the 33, 23 met inclusion criteria (completed preinjection and post-BT injection surveys, with and without buccinator injections). Demographic data, etiology of facial paralysis, and dosing details are outlined in Table 1. The 23 patients meeting inclusion criteria presented for 82 treatment visits, with a median of 4 visits per patient. Of these visits, 44 (53.6%) involved buccinator injections and 38 (46.4%) were without buccinator injections. Only 6 visits were new patient encounters, with most patients having a medical history of BT treatment prior to the start of the data collection period (mean treatment duration, 36 months). Mean (SD) age of patients was 46.0 (10.4) years, with 9 women making up 82.6% of the participants. Etiology of facial paralysis included 10 patients with vestibular schwannoma (43.5%) and 9 patients with Bell Palsy (39.1%).

Table 1. Patient and Treatment Visit Characteristics.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Total patients | 23 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46 (10.4) |

| Female, No. (%) | 19 (82.6) |

| Etiology of facial paralysis, No. (%) | |

| Bell palsy | 9 (39.1) |

| Vestibular schwannoma | 10 (43.5) |

| Trauma | 1 (4.3) |

| Ramsay-Hunt | 3 (13.0) |

| Total injection visits | 82 |

| Buccinator injections, No. (%) | 44 (53.6) |

| History of prior injections, No. (%) | 76 (92.7) |

| Total dose, mean (SD), units | 31.9 (13.1) |

| Buccinator dose, median (SD), units | 2.5 (3.75) |

Patient treatment outcomes are summarized in Table 2. When considering both nonbuccinator and buccinator treatment cycles together, the mean (SD) pretreatment and posttreatment SAQ scores were 63.9 (15.0) (95% CI, 60.5-67.2) and 44.5 (13.6) (95% CI, 41.5-47.5), respectively, (P < .001). Subgroup analysis revealed similar significant differences in mean pretreatment and posttreatment scores during treatment cycles without buccinator injections (64.2; 95% CI, 58.0-68.9 vs 42.8; 95% CI, 41.3-50.4; P < .001) and with buccinator injections (63.5; 95% CI, 60.1-68.3 vs 45.9; 95% CI, 38.8-46.8; P < .001). Overall, the mean (SD) difference between pretreatment and posttreatment SAQ questionairre scores was 18.4 (10.7) and duration of BT effect was 66.2 (13.4) days.

Table 2. Overall Treatment Outcomes.

| Treatment | Mean (SD) [95% CI] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean SAQ Score | P Value | Mean Absolute Difference | Duration of Effect, d | ||

| Pretreatment | Posttreatment | ||||

| Combined treatmentsa | 63.9 (15.0) [60.5-67.2] | 44.5 (13.6) [41.5-47.5] | <.001 | 18.4 (10.7) [16.1-20.8] | 66.2 (13.4) [63.3-69.2] |

| Buccinator treatment cycle | 64.2 (13.9) [58.0-68.9] | 42.8 (13.6) [41.3-50.4] | <.001 | 19.0 (9.5) [14.2-21.8] | 66.8 (14.5) [61.7-69.6] |

| Non-buccinator treatment cycle | 63.5 (16.5) [60.1-68.3] | 45.9 (13.7) [38.8-46.8] | <.001 | 18.0 (11.7) [16.2-21.8] | 65.7 (12.0) [62.5-71.1] |

Abbreviation: SAQ, Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire.

Including treatment cycles with and without buccinator injections.

Table 3 summarizes the comparative outcomes between patient treatment cycles with and without buccinator injections. Mean baseline pre-BT injection scores with and without buccinator injections were similar (64.3; 95% CI, 58.0-68.9 vs 63.5; 95% CI,60.1-68.3; P = .81). Subanalysis of buccinator-specific scores similarly showed no difference in mean pre-BT injection values (7.2; 95% CI, 6.7-7.7 vs 7.6; 95% CI, 6.9-8.3; P = .31). Compared with treatment cycles in which the buccinator was not addressed, buccinator injections resulted in lower total postinjection SAQ scores (45.9; 95% CI, 38.8-46.8 vs 42.8; 95% CI, 41.3-50.4; P = .43) and greater differences in pre- and post-BT outcomes (18; 95% CI, 16.2-21.8 vs 19; 95% CI, 14.2-21.8; P = .73), although these differences were not significant. Subanalysis of buccinator-specific scores, however, did reveal significantly improved post-BT injection scores with the addition of buccinator injections (5.7; 95% CI, 5.0-6.4 vs 4.1; 95% CI, 3.7-4.6; P = .004). This corresponded to greater differences in pre- and post-BT scores after patients were treated with buccinator injections (3.3; 95% CI, 2.7-3.9 vs 2.0; 95% CI, 1.4-2.6; P = .02). The duration of BT effect was similar both with and without buccinator treatment (66.8; 95% CI, 61.7-69.6 vs 65.7; 95% CI, 62.5-71.1; P = .72).

Table 3. Comparative Treatment Outcomes With and Without Buccinator Treatment.

| Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire Scores | Mean (SD) [95% CI] | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without Buccinator Treatment | With Buccinator Treatment | ||

| Pretreatment SAQ Score | |||

| Total | 63.5 (16.5) [60.1-68.3] | 64.2 (13.9) [58.0-68.9] | .81 |

| Buccinator-specific | 7.6 (2.1) [6.9-8.3] | 7.2 (1.7) [6.7-7.7] | .31 |

| Posttreatment SAQ Score | |||

| Total | 45.9 (13.7) [38.8-46.8] | 42.8 (13.6) [41.3-50.4] | .43 |

| Buccinator-specific | 5.7 (2.1) [5.0-6.4] | 4.1 (1.5) [3.7-4.6] | .004 |

| Absolute Difference | |||

| Total | 18.0 (11.7) [16.2-21.8] | 19.0 (9.5) [14.2-21.8] | .73 |

| Buccinator-specific | 2.0 (1.9) [1.4-2.6] | 3.3 (1.9) [2.7-3.9] | .02 |

| Duration of effect | 65.7 (12.0) [62.5-71.1] | 66.8 (14.5) [61.7-69.6] | .72 |

Abbreviations: SAQ, Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire.

Discussion

Botulinum toxin is the gold standard for treating synkinetic muscles in the setting of facial paralysis of various etiologies.4,5 A variety of muscles in the perioral and midface region have been targeted to address patient complaints of facial tightness and involuntary lip movements with success.1,3,4,8,9,11,12 Until recently, the buccinator muscle has been neglected as a target for BT therapy. Intuitively, the considerable muscle bulk of the buccinator in the midface, its role in posterior movement of the oral commissure, and the relative proximity to multiple branches of the facial nerve with theoretical increased risk of aberrant innervation, makes this a prime target for symptom improvement.4,14 This was aptly identified in a recent study by Wei et al,14 who demonstrated the feasibility and treatment approach for injecting the buccinator, as well as the positive outcomes of BT treatment on the validated SAQ synkinesis questionnaire.15

One limitation of the study by Wei et al14 was the simultaneous treatment of other facial muscles during buccinator treatment. Thus, it was unclear if the improvement between the pre-BT and post-BT injection SAQ scores reflected a benefit secondary to treatment of the buccinator muscle. Nonetheless, the authors did note an overall positive consensus among patients receiving buccinator injections.

Our study was therefore performed to isolate the benefit of buccinator injections in the treatment of facial synkinesis. In particular, SAQ outcomes were compared between treatment cycles in which patients did not receive a buccinator injection to their subsequent treatment cycles in which this muscle was treated. As such, a patient’s outcomes with buccinator treatment could be compared to his or her own baseline SAQ score. Although 33 patients of the 84 being treated at our institution during the study period were injected with buccinator injections, only 23 of them completed pre- and post-BT SAQ surveys in both with-buccinator and without-buccinator conditions. In our overall treatment population of 84 participants, Bell palsy was the most common etiology of facial paralysis, with 34 (40.5%) patients, similar to other studies.9,14,15,16 However, in this study cohort 9 (39.1%) patients with synkinesis had initial presentation of Bell palsy compared with 10 (43.5%) who underwent resection of a vestibular schwannoma. In addition, similar to other studies, most patients were women (82.6%) with a mean age falling in the fourth decade of life.9,14,15,17 Notably, the relatively younger patient population experiencing facial synkinesis compared with many other chronic diseases and resulting impact on quality of life makes it important to maximize patient benefits with BT injections. This includes determining optimal musculature injection sites during treatment.

Similar to Wei et al14 and other authors, we show that patients treated with BT have improved SAQ post-BT injection scores when compared with pre-BT scores.3,15 All 23 patients in this cohort had improvement in their SAQ scores, with mean pre- and post-BT scores of 63.9 and 44.5, respectively. This is consistent with the established data that BT is an effective treatment of muscle hypertonicity in synkinesis.

When stratified by buccinator and non-buccinator treatments, the beneficial effect of BT was maintained. When comparing patient SAQ scores between buccinator and non-buccinator treatments, there was no notable difference in baseline pre-BT scores. However, patients treated with buccinator injections did have nonsignficant improvements in post-BT treatment scores and, when isolating questions from the survey relevant to buccinator motion (ie, facial tightness and mouth movement), this improvement with buccinator injections became significant. To account for variability in pre-BT and post-BT scores among patients, the absolute difference of these scores was calculated. When receiving buccinator injections, patients had greater absolute benefit in total SAQ and buccinator-specific SAQ scores, the latter of which was significant. As expected, the benefit of buccinator injections was not as evident on total SAQ scores as it was on buccinator-specific questions. The SAQ questionnaire measures global synkinesis, with most questions evaluating facial muscles not related to the midface or oral cavity (ie, ocular muscles or neck). Thus, the SAQ in clinical practice may not be sensitive enough to evaluate outcomes of specific muscle group treatments.

An additional divergence from Wei et al,14 described herein is the use of EMG-guided needles in targeting the buccinator muscle. It has been demonstrated that EMG guidance can detect slight synkinesis that may be missed on visual inspection alone.18 Identifying buccinator muscle hyperactivity visually is challenging, and passes that appear to be in the muscle belly visually frequently need to be adjusted to elicit a strong signal on EMG. Confirmation of synkinetic ocularoral reinervation of the buccinators is possible by identifying increased EMG signal associated with eye closure. This is thought to allow for more precise delivery of BT into the affected muscle belly. As a consequence, a larger bore needle must be used at the expense of patient comfort. Applying topical anesthetic to the buccal mucosa before injection may offset this. In addition, multiple injections along the belly of the buccinator muscle were not performed, again diverging from the technique used by Wei et al.14 The efficacy of EMG in patient outcomes may be a topic of further study.

A recently raised concern about injection of the buccinator is its proximity to the parotid duct and the associated theoretical risk of either sialorrhea (owing to decrease in periduct muscle contraction) or sialolithiasis.19 Consistent with the literature, we did not encounter any patient-reported salivary dysfunction as a result of buccinator injection. While a theoretical concern is well founded, most buccinator muscle bulk lies more anterior to the region of the parotid duct, and combined knowledge of the anatomy and use of EMG guidance allows for targeted injection without collateral consequence. Importantly, because buccinator treatment is a new practice at our center, dosing choice reflected known efficacious doses for other midface muscles (median, 2.5 U). It remains unclear what the upper threshold for dosing is in regards to optimizing patient symptoms while minimizing adverse effects, such as cheek flaccidity.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Our sample size was limited by strict inclusion criteria (pre- and post-BT treatment in both with and without buccinator conditions), which inherently decreases the power. This also prevented further subgroup analyses of age, etiology of disease, or dose on treatment outcomes. Synkinesis is an evolving disorder, one that can result in different symptomology and need for altering treatment over time. This variability can impact the validity of comparisons between buccinator and no-buccinator treatment cycles. However, only 6 patients were newly treated during this study. Most were in a relatively stable state with regard to their synkinesis with a mean 45-month treatment duration.

The 6 BT-targeted muscles at our center that impact midface tightness or lip corner movement are the levator labii superioris, zygomaticus, orbicularis oris superioris, risorius, orbicularis oris inferioris, and depressor anguli oris. Thirteen patients had no change in either dosing or treatment of these mimetic muscles between buccinator and no-buccinator treatment cycles. Of the 10 patients that did have some change, 1 had the same muscles (zygomaticus and depressor anguli oris) injected at a higher dose, 3 had a new muscle injected, and 6 had a muscle that was no longer treated. With more patients losing rather than gaining treatment to other mimetic muscles with the addition of buccinator injections, we would expect that the positive outcomes reported are not confounded by the benefits of treating other facial muscles. To further confirm this, a subanalysis exluding the 4 patients who received additional treatment to facial muscles with buccinator treatment was performed, and we continued to find improved buccinator-specific SAQ scores (pretreatment, 7.7; 95% CI, 7.1-8.4 vs 7.3; 95% CI, 6.8-7.7, P = 0.21; postreatment, 5.8; 95% CI, 5.1-6.5 vs 4.2; 95% CI: 3.7-4.7, P = .004; difference, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.4-2.6 vs 3.2; 95% CI, 2.7-3.8; P = .04). Similar outcomes were noted when all 10 patients with a change in treatment were excluded (pretreatment, 7.4; 95% CI, 6.6-8.3 vs 7.3; 95% CI, 6.8-7.9; P = .85; postreatment, 5.7; 95% CI, 4.9-6.8 vs 4.3; 95% CI, 3.6-4.9; P = .04; difference, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.0-2.6 vs 3.3; 95% CI, 2.5-4.0; P = .06).

Because the treatment of buccinator injections was overall perceived as being beneficial, a balanced crossover design in which a similar number of patients temporally experienced buccinator treatments prior to treatment cycles without no-buccinator injections was not possible (ie, the withdrawal of a perceived beneficial treatment would be unethical). Finally, while the SAQ questionnaire provides a patient-centered assessment of severity of facial synkinesis, it does not allow for measures of objective facial disfigurement. Physician-driven assessments, including the Sunnybrook and House-Brackmann facial grading scale, have been used to measure BT outcomes in multiple studies of synkinesis; however, it remains unclear how the validated SAQ questionnaire correlates with these scales.1,3,9,17,20 Our findings indicate that the addition of the buccinator muscle as a target has significantly improved patient outcomes. Future directions of inquiry may include determining the efficacy of EMG-guided buccinator injections, optimal dosing, and additional metrics measuring objective outcomes in this patient population.

Conclusions

In patients with facial synkinesis, BT injections of the buccinator effectively add benefit to subjective severity of disease. This intervention can be safely used in well-selected patients who are simultaneously undergoing injections of other synkinetic facial musculature with facial rehabilitation.

References

- 1.Choi KH, Rho SH, Lee JM, Jeon JH, Park SY, Kim J. Botulinum toxin injection of both sides of the face to treat post-paralytic facial synkinesis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(8):1058-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu L, Bundy C, Sadiq SA. Psychological distress in people with disfigurement from facial palsy. Eye (Lond). 2011;25(10):1322-1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filipo R, Spahiu I, Covelli E, Nicastri M, Bertoli GA. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of facial synkinesis and hyperkinesis. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(2):266-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehdizadeh OB, Diels J, White WM. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of facial paralysis. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2016;24(1):11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Husseman J, Mehta RP. Management of synkinesis. Facial Plast Surg. 2008;24(2):242-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couch SM, Chundury RV, Holds JB. Subjective and objective outcome measures in the treatment of facial nerve synkinesis with onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox). Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(3):246-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chua CN, Quhill F, Jones E, Voon LW, Ahad M, Rowson N. Treatment of aberrant facial nerve regeneration with botulinum toxin A. Orbit. 2004;23(4):213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borodic GE, Pearce LB, Cheney M, et al. Botulinum A toxin for treatment of aberrant facial nerve regeneration. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91(6):1042-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toffola ED, Furini F, Redaelli C, Prestifilippo E, Bejor M. Evaluation and treatment of synkinesis with botulinum toxin following facial nerve palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(17):1414-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borodic G, Bartley M, Slattery W, et al. Botulinum toxin for aberrant facial nerve regeneration: double-blind, placebo-controlled trial using subjective endpoints. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(1):36-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laskawi R, Damenz W, Roggenkämper P, Baetz A. Botulinum toxin treatment in patients with facial synkinesis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1994;S195-S199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers CR, Schmidt KL, VanSwearingen JM, et al. Automated facial image analysis: detecting improvement in abnormal facial movement after treatment with botulinum toxin A. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58(1):39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran CJ, Neely JG. Patterns of facial nerve synkinesis. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(12 Pt 1):1491-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei LA, Diels J, Lucarelli MJ. Treating buccinator with botulinum toxin in patients with facial synkinesis: a previously overlooked target. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;32(2):138-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta RP, WernickRobinson M, Hadlock TA. Validation of the Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(5):923-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong MW, Mountain RE, Murray JA. Treatment of facial synkinesis and facial asymmetry with botulinum toxin type A following facial nerve palsy. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1996;21(1):15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dall’Angelo A, Mandrini S, Sala V, et al. Platysma synkinesis in facial palsy and botulinum toxin type A. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(11):2513-2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.On AY, Yaltirik HP, Kirazli Y. Agreement between clinical and electromyographic assessments during the course of peripheric facial paralysis. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(4):344-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chundury RV, Perry JD. Re: “Treating buccinator with botulinum toxin in patients with facial synkinesis: a previously overlooked target.” Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;32(1):70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fattah AY, Gurusinghe AD, Gavilan J, et al. ; Sir Charles Bell Society . Facial nerve grading instruments: systematic review of the literature and suggestion for uniformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(2):569-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]