Abstract

Reticulocyte-derived exosomes (Rex), extracellular vesicles of endocytic origin, were initially discovered as a cargo-disposal mechanism of obsolete proteins in the maturation of reticulocytes into erythrocytes. In this work, we present the first mass spectrometry-based proteomics of human Rex (HuRex). HuRex were isolated from cultures of human reticulocyte-enriched cord blood using different culture conditions and exosome isolation methods. The newly described proteome consists of 367 proteins, most of them related to exosomes as revealed by gene ontology over-representation analysis and include multiple transporters as well as proteins involved in exosome biogenesis and erythrocytic disorders. Immunoelectron microscopy validated the presence of the transferrin receptor. Moreover, functional assays demonstrated active capture of HuRex by mature dendritic cells. As only seven proteins have been previously associated with HuRex, this resource will facilitate studies on the role of human reticulocyte-derived exosomes in normal and pathological conditions affecting erythropoiesis.

Introduction

Research on exosomes is gaining momentum as these vesicles of endocytic origin act in intercellular communication and represent novel therapeutic strategies and non-invasive biomarkers of disease1–3. During their maturation to erythrocytes, reticulocytes selectively remove proteins, noticeably the transferrin receptor (TfR or CD71), as well as membrane-associated enzymes, through the formation of multivesicular bodies which after fusion with the plasma membrane release intraluminal vesicles, termed exosomes4–6.

Studies on the protein cargo composition of reticulocyte-derived exosomes (Rex) are mostly limited to animal models and validations through non high-throughput technologies7–9. These studies clearly established that Rex represent a selective cargo disposal mechanism in the terminal maturation of reticulocytes into erythrocytes7. More recently, mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomic analysis of Rex from phenylhydrazine-treated rats10 and from mice infected with rodent malaria parasites with a unique tropism to reticulocytes11, described the proteome of Rex in these species. Results reinforced the view that Rex have selective cargo and demonstrated for the first time that Rex from malaria-infected reticulocytes contain parasite antigens involved in antigen presentation and capable of modulating immune responses11,12. To our knowledge, however, only seven proteins (TfR, Stomatin, Flotillin-1 and 2, CD55, CD58 and CD59) have been previously reported in human Rex7,13,14.

In this work, we present the first MS-based proteomic profile of human reticulocyte-derived exosomes (HuRex). HuRex were isolated from cultures of human cord blood using two different culture conditions, absence/presence of exosome-depleted serum, and two different exosome isolation techniques, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and ultracentrifugation (UC). The proteome consists of 367 proteins most of which have not been previously reported. Immunoelectron microscopy validated the presence of the transferrin receptor, a major Rex component, and comparative analysis with the MS-datasets from reticulocytes15–17 and mature red blood cells17–20, rendered a selected list of HuRex plasma membrane and cytosol proteins. In addition, we identified proteins involved in antigen presentation and observed an active capture of HuRex by mature dendritic cells. These results thus provide a first base-line proteome of HuRex enabling further studies not only on their biogenesis and antigen-presenting capacity, but also on their cargo composition in diseases affecting erythropoiesis.

Results

Enrichment of human reticulocytes and in vitro production and characterization of human reticulocyte-derived exosomes

Enriched reticulocyte samples were obtained from human blood of umbilical cords, a source with higher percentage of reticulocytes than adult humans’ blood and with no major proteomic differences between them17. After removal of leukocytes and concentration on Percoll gradients (Supplementary Fig. S1), yield percentages of reticulocytes ranged between 20 to 60% among different donors. Reticulocytes were subsequently cultured in vitro for 36 h at 1–3% hematocrit. Of note, our cultures contain significant percentages of mature red blood cells, yet these cells lack endocytic machinery and it has been clearly established that they do not secrete exosomes6,21. Furthermore, we discarded reticulocyte-enriched preparations that contained over 2% of contaminating leukocytes to minimize the presence of leukocyte-derived vesicles in the cultures. We refrained from using CD71 affinity bead purification as there is a large heterogeneous population of reticulocytes from CD71negative to CD71high22. HuRex were produced in vitro in the presence or absence of serum, previously depleted of exosomes, as there is evidence suggesting that the protein cargo varies significantly in the absence of serum23. Before and after culture, cell viability was assessed by microscopy using Trypan Blue stain. We demonstrated 95.6 ± 2.1% of cell viability after 36 hours of culture independently of serum supplementation. Thus, excluding a major proteomic confounding due to apoptotic vesicles in culture supernatants. It has also been emphasized that another factor affecting the quality of exosome preparations is the method of purification24; therefore, we purified HuRex by either UC25 or SEC26. The use of sequential centrifugation removing most apoptotic bodies (1,300 g pellet) and microvesicles (15,000 g pellet)25 and the use of SEC also removing these types of vesicles26, further emphasizes that we are mostly isolating exosomes derived from reticulocytes27. Due to intrinsic variability of human samples and the lack of a unique method for isolation of exosomes, however, we cannot exclude the possibility that a small number of these proteins are wrongly assigned to exosomes derived from reticulocytes.

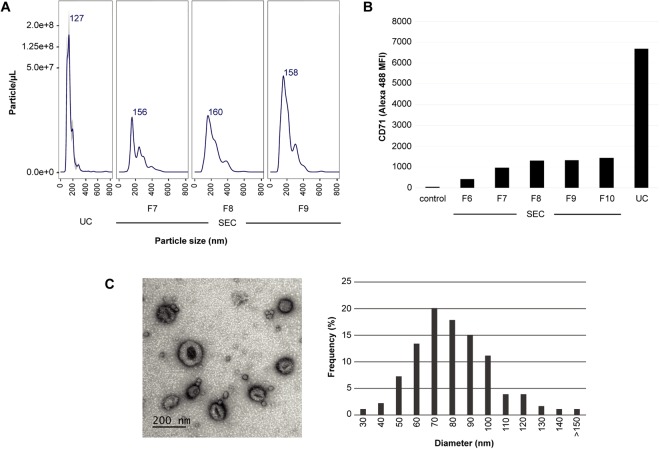

HuRex were first subjected to Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA). Results demonstrated that HuRex were homogeneous with a mean size of 127 nm and that particle concentration was in the range of 108 particles/µL. Particle concentration from SEC fractions was always lower than that from UC (Fig. 1A). We determined the presence of the major component of Rex: the transferrin receptor, CD714,5,8 by beads-based flow cytometry. Higher MFI values for UC compared to those for SEC were always observed (Fig. 1B). To confirm vesicle integrity, HuRex preparations obtained by UC were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) by means of negative staining (Fig. 1C). As expected from fixation and dehydration28, size distribution of TEM images revealed smaller vesicle mean size (70 nm), than that recorded by NTA (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Isolation and characterization of exosomes derived from human cord blood reticulocytes. (A) NTA profiles of HuRex from ultracentrifugation (UC) and size exclusion chromatography (SEC) fractions. Concentration is shown in particle/µL. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of transferrin receptor, CD71, in HuRex. MFI, Median Fluorescence Intensity. (C) Electron microscopy. Representative TEM image on the left. Bar represents 200 nm. Size distribution from TEM images quantified by ImageJ on the right. nm, nanometers.

Detection of the transferrin receptor on human reticulocyte-derived exosomes

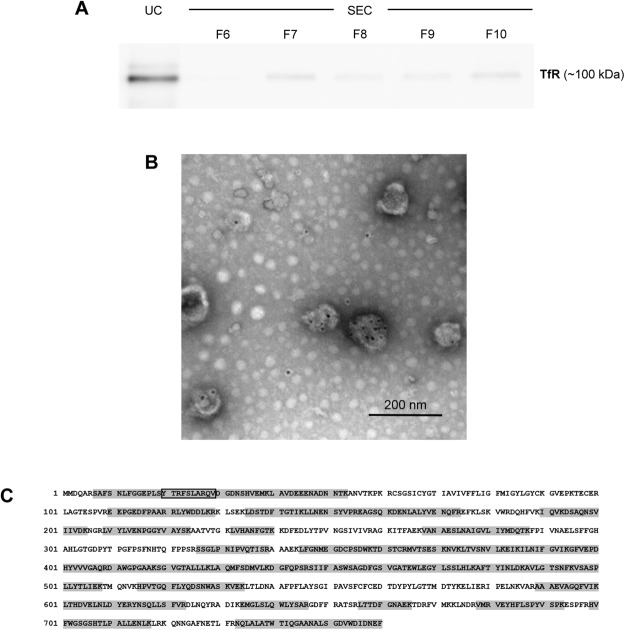

The transferrin receptor is completely and selectively removed in exosomes during the terminal differentiation of reticulocytes into erythrocytes4,5,8. We first analyzed the presence of this protein by immunoblot in HuRex purified by UC and SEC (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S2). As expected from concentration of particles/µL (Fig. 1A), a higher signal was observed in the UC preparation as compared to SEC fractions. Next, immunoelectron microscopy demonstrated that TfR is associated with exosomes corroborating their reticulocyte origin (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Detection of the transferrin receptor (TfR) in human reticulocyte-derived exosomes. (A) Immunoblot in HuRex purified by UC and SEC fractions. (B) Immunogold labelling of UC-HuRex using a secondary antibody conjugated to 10 nm-gold spheres. Scale bar represents 200 nm. (C) Protein coverage by unique peptides (grey boxes) identified by MS. The peptide sequence YTRFSLARQV, corresponding to the binding domain of TfR for hsc7142, is boxed in black. UniProtKB – P02786 TfR sequence is shown.

Proteomic analysis of human reticulocyte-derived exosomes

Characterization by mass spectrometry, LC-MS/MS, was performed over HuRex from six different cord blood donors to determine their molecular composition. As research on the molecular cargo of exosomes is largely confounded by the lack of a “gold-standard” methodology24, we applied several approaches for obtaining HuRex prior to MS. HuRex preparations were obtained in absence of serum (AS) from three donors and isolated by means of SEC (n = 3) and UC (n = 3). HuRex preparations in the presence of serum were obtained from three other donors and purified by SEC (n = 3) and UC (n = 1). In total, 367 different proteins were identified in the 10 MS-dataset according to UniProt accessions, although protein numbers from each cord blood were different from each other due to the intrinsic variability of such samples (Supplementary Table S1). Nevertheless, most of the proteins identified by SEC are a subset of the ones identified by UC (not shown). Thus, after removal of leukocytes, the use of SEC and culturing of human reticulocytes from cord blood in the presence of serum, depleted of exosomes, seems a robust method for furthering studies of HuRex. To further verify the reticulocyte origin of exosomes4,5,8, we first demonstrated the presence of TfR in all MS-datasets (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, 45 unique peptides, including the sequence YTRFSLARQV previously shown to interact with hsc7029, and covering 64.08% of this receptor, were identified (Fig. 2C). Further western blotting analysis on these vesicles confirmed the detection of the raft-associated protein stomatin, previously associated to HuRex14 and verified the identification of newly detected proteins such as HSP70 and GAPDH (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. S2).

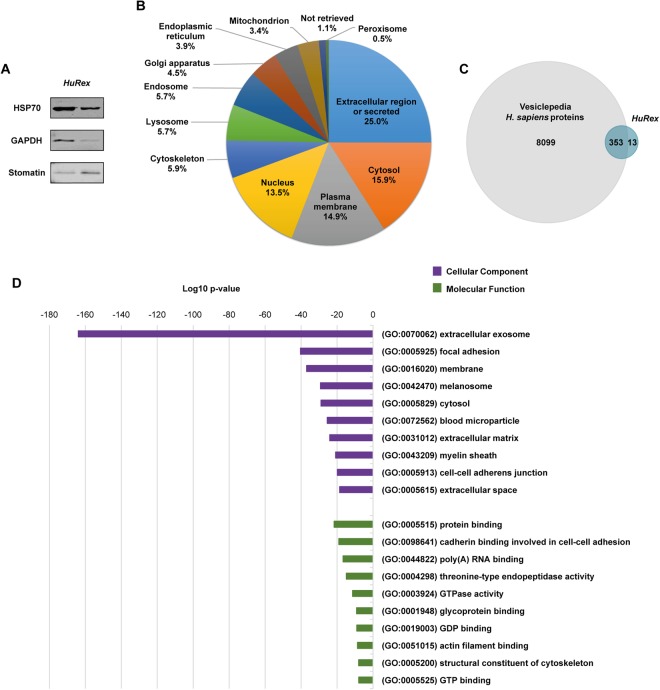

Figure 3.

Proteome of human reticulocyte-derived exosomes identified by LC-MS/MS. (A) Western blot validation for HSP70, GAPDH and stomatin on UC-HuRex. Samples were purified from two cord blood donors, each one loaded in a different lane. (B) Distribution of the proteome of HuRex in subcellular location categories retrieved from UniProt database according to Gene Ontology (GO) annotation. (C) Venn diagram showing the overlap of proteins detected in HuRex and those reported in Vesiclepedia, a database of extracellular vesicle cargo30. (D) GO term-enrichment analysis of HuRex proteome at cellular component and molecular function level performed with Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (David 6.8)60. The most over-represented GO terms are shown.

Proteins were assigned different subcellular locations and percentages according to Gene Ontology (GO) annotation obtained from UniProt: Extracellular region (25.0%), Cytosol (15.9%), Plasma membrane (14.9%), Nucleus (13.5%), Cytoskeleton (5.9%), Lysosome (5.7%), Endosome (5.7%), Golgi apparatus(4.5%), Endoplasmic reticulum (3.9%), Mitochondrion (3.4%), “Not retrieved” (1.1%) and Peroxisome (0.5%) (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S1). Of note, most of the proteins identified in this work were already listed in Vesiclepedia, a public data repository for extracellular vesicle cargo30 (Fig. 3C). Moreover, in agreement with these data, over-represention GO analysis of cellular component revealed that the bulk of proteins identified in HuRex correspond to extracellular exosome (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Table S2). According to the idea that HuRex remove adhesins7,8, GO analysis of molecular function revealed protein binding as a major function of HuRex (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Table S2).

Biochemical analysis of exosomes obtained from sheep reticulocytes originally demonstrated that in addition to TfR several membrane enzymes and transporters were also selectively removed by exosomes6. Accordingly, we identified several of such and other membrane proteins, namely, Na+/K+ transporting ATPase (ATP1A1, ATP1B3), calcium-transporting ATPase (ATP2B4), neutral amino acid transporters (SLC1A5, SLC43A1, SLC7A5), and glucose transporters 1, 2, 3 and 4 (SLC2A1, SLC2A2, SLC2A3, SLC2A4). A notable exception was acetylcholinesterase which was reported to have high activity in the original description of exosomes6. Other MS studies of human reticulocytes and reticulocyte-derived exosomes from other species10,15 have also failed to detect this enzyme, but without other alternative method confirming its absence, we cannot rule out this is due to technical issues. Several other plasma membrane proteins previously not reported in HuRex were identified in our analysis. These include several integrins alpha and beta (ITGA2B, ITGA4, ITGAM, ITGB1, ITGB2, ITGB3) and transporters (SLC6A9, SLC7A1) among others (Supplementary Table S1).

Previous functional enzymatic analyses of reticulocyte-derived exosomes revealed little or no activity of the cytosolic enzymes lactate dehydrogenase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase6. All these enzymes were identified in our MS analysis, albeit with different coverage and numbers of unique peptides (Supplementary Table S1). Of note, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate is inactive when binding to band 331 but this explanation for the lack of activity was discarded as band 3 was not acknowledged to be present in reticulocyte-derived exosomes6. Yet, our studies identified band 3 suggesting this alternative explanation. Other cytosolic enzymes and proteins associated with HuRex are worth mentioning. Several Rab GTPases were identified, in particular Rab7a, Rab11b, and Rab14. In contrast, we failed to identify Rab27, known to play a main role in exosome biogenesis in other cells32. Similarly to acetylcholinesterase, further experimentation would be required to demonstrate its absence or by the contrary, prove its association to HuRex. We also detected five S100 proteins, calcium-modulated proteins pertaining to a vertebrate multigene family which in humans contain 24 members33. Notoriously, we identified S100-A9 with a coverage of 89.47%, a protein that has been recently found in plasma-derived exosomes associated to chronic lymphocytic leukemia34. We have identified several histones, including histone H4 previously shown to be largely exported to the cytoplasm15. Last, we and others15 failed to identified Tsg101, a major player in the biogenesis of exosomes in other cells35.

We crossed HuRex proteome with reported red cell MS proteomes from human reticulocytes15–17 and mature RBCs17–20. For that we first compared the cell proteomes (Supplementary Fig. S3) and we defined a reticulocyte core proteome of 587 proteins and a mature RBC core proteome consisting of 1055 proteins. The intersection of HuRex proteins with the core proteomes of reticulocytes and matured RBCs (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Supplementary Table S3) showed that many of the proteins identified in HuRex are also detected in these works, most of them associated to plasma membrane and cytosol (Supplementary Table S3). Moreover, when we performed a direct comparison of the proteins identified in HuRex with the mentioned human reticulocyte proteomes15–17, around 70% of the proteins described in HuRex have been detected in their cell of origin (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Even though in this first MS proteomic description of HuRex we focused on protein identification, we calculated the normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF)36 (one of the most common protein quantification indexes used in label-free quantificacion proteomics based on the spectral counting)37 to estimate relative protein abundance. We observed that previously detected proteins in HuRex such as TfR and stomatin, as well as newly identified like S100A9 and HSPA8 were found among the 50 most abundant proteins (Supplementary Fig. S4 and Supplementary Table S5).

Capture of HuRex by dendritic cells

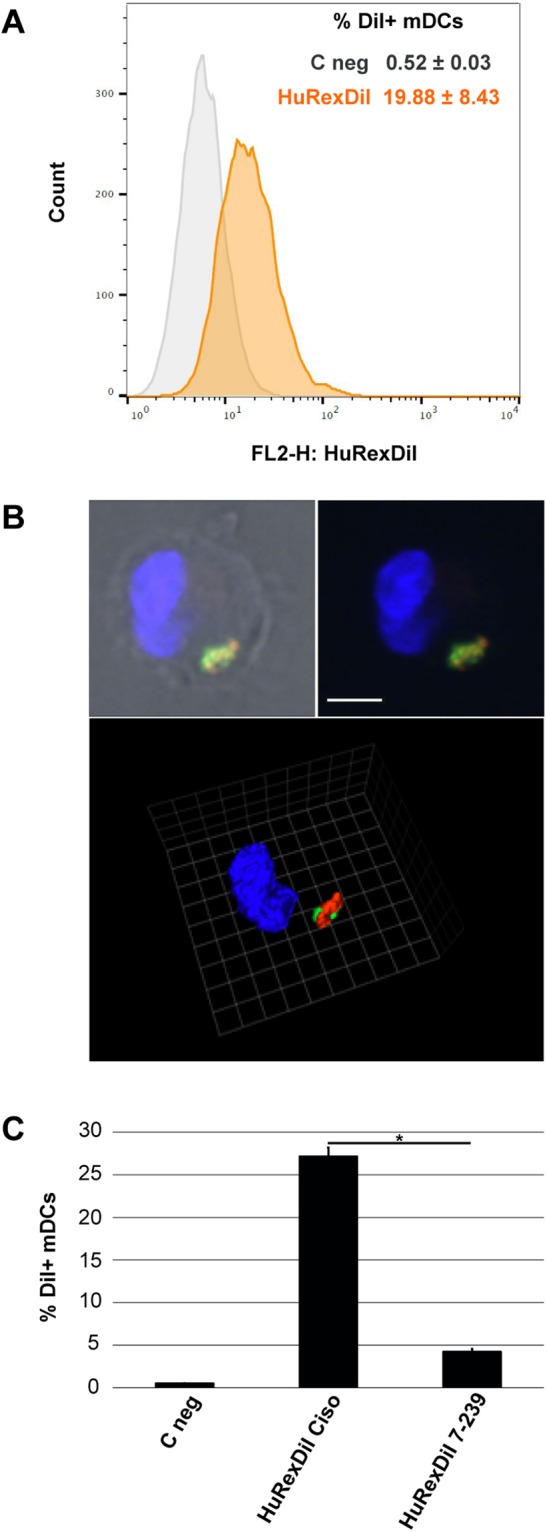

MHC class-I molecules are involved in antigen presentation where professional antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells are usually required to process and present antigens to T cells2. As we detected HLA class-I antigens in HuRex and our own previous results demonstrated the presence of MHC class-I molecules in exosomes from rodent malaria infections11,12, we decided to run a functional assay to determine if HuRex could be uptaken by dendritic cells (DCs). This assay had previously demonstrated that the sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectin 1, Siglec-1, is responsible for exosome capture on mature DCs and follows the same trafficking route as HIV-1 particles38,39. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that 19 ± 8% of activated monocyte-derived dendritic cells (mDCs) actively uptake HuRex labeled with Dil (HuRexDiI) (Fig. 4A). We next assessed if HuRexDiI were retained within the same sub-cellular compartment as fluorescent HIV-1 VLP. As shown in Fig. 4B and Video 1, mDCs exposed to HuRexDiI and subsequently exposed to HIV-1 VLP retained both types of vesicles within the same sack-like compartment, as analyzed by confocal microscopy. Last, pretreatment of mDCs with a monoclonal antibody against Siglec-1 significantly inhibited HuRexDiI capture, T-test P < 0.05 (Fig. 4C). Thus, HuRex are efficiently captured by mDCs via Siglec-1.

Figure 4.

Siglec-1 dependent capture of human reticulocyte-derived exosomes by mature dendritic cells. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of HuRexDiI capture by mDCs. (B) Confocal microscopy co-localization of HuRexDiI (in red) and VLPHIV-Gag-eGFP (in green) in mDCs (nuclei stained with DAPI). Top: z-plane showing fluorescence and bright field (scale bar 5 μm); Bottom: 3D reconstruction of z-planes (reference scale unit 2,48 μm). (C) Inhibition of HuRexDiI capture by mDCs by blocking of Siglec-1 with α-Siglec-1 mAb. mDCs not treated with antibodies nor with HuRexDiI were incubated in parallel (C neg). Data show mean values and SD from 2 donors. T-test P < 0.05.

Discussion

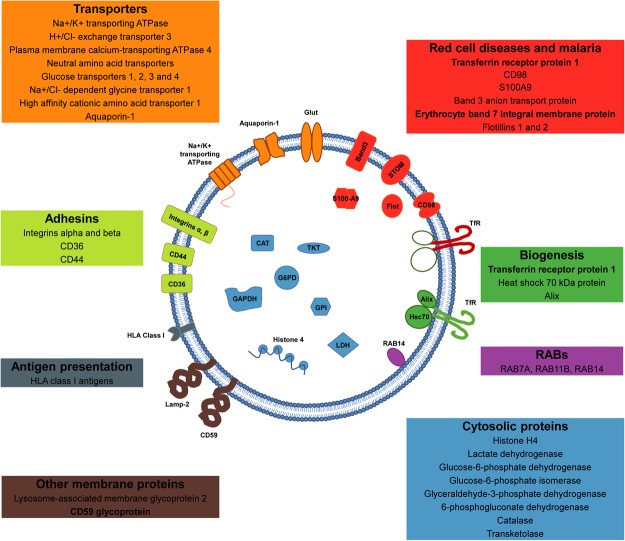

Here, we present the first mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis of human reticulocyte-derived exosomes (HuRex) consisting of 367 proteins. Previously, MS proteomes from human reticulocytes15–17, and mature RBCs17–20, had been reported. When comparing this novel HuRex proteome with those proteomes, we found many common proteins, especially from plasma membrane and cytosol (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Supplementary Table S3). These data are largely in agreement with the idea that exosomes reflect a “cell biopsy”, but at the same time are enriched in specific cargo1,40. In addition, the complete MS proteome of reticulocyte-derived exosomes from rats is available10 and its comparison with the HuRex proteome revealed more than 200 conserved proteins (Supplementary Table S4). This dataset thus represents the first comprehensive list of proteins from human reticulocyte-derived exosomes and a valuable resource to pursue different studies (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

The human reticulocyte-derived exosome proteome. Schematic illustration of a human reticulocyte-derived exosome highlighting selected plasma membrane and cytosolic proteins. Transporters (in orange): Na+/K+ transporting ATPase (ATP1A1, ATP1B3), H+/Cl− exchange transporter 3 (CLCN3), Plasma membrane calcium-transporting ATPase 4 (ATP2B4), Neutral amino acid transporters (SLC1A5, SLC43A1, SLC7A5), Glucose transporters 1, 2, 3 and 4 (SLC2A1, SLC2A2, SLC2A3, SLC2A4), Na+/Cl− dependent glycine transporter 1 (SLC6A9), High affinity cationic amino acid transporter 1 (SLC7A1) and Aquaporin-1 (AQP1). Adhesins (in lime): Integrin alpha and beta (ITGA2B, ITGA4, ITGAM, ITGB1, ITGB2, ITGB3), CD36 and CD44. Other membrane proteins (in brown): Lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 2 (LAMP2) and CD59 glycoprotein (CD59). Antigen presentation (in grey): HLA class I antigens (HLA-A, HLA-C). RABs (in pink): RAB7A, RAB11B and RAB14. Biogenesis (in green): Transferrin receptor protein 1 (TFRC), Heat shock 70 kDa protein (HSPA8, HSPA1A) and Alix (PDCD6IP). Cytosolic proteins (in blue): Histone H4 (HIST1H4A), Lactate dehydrogenase (LDHA, LDHB), Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI), Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (PGD), Catalase (CAT) and Transketolase (TKT). Red cell diseases and malaria (in red): Transferrin receptor protein 1 (TFRC), CD98 (SLC3A2, SLC7A5), S100A9, Band 3 anion transport protein (SLC4A1), Erythrocyte band 7 integral membrane protein (STOM) and Flotillins 1 and 2 (FLOT1, FLOT2). Proteins in bold have been previously described in human reticulocyte-derived exosomes (TfR, STOM, CD59)7,13,14.

The endocytic pathway in reticulocytes differs from other cells as lysosomes are almost completely absent. Moreover, as a Golgi apparatus and an endoplasmic reticulum are also vestigial, it is reasonable to think that complex and diverse sorting pathways are absent from reticulocytes. Thus, the final step in this differentiation should be considered the MVB-exosomal release41. Elegant studies on the fate of the TfR during reticulocytes maturation using rodent and sheep models demonstrated that this receptor specifically interacts with the heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein29. Moreover, it was later shown that the hydrophobic peptide sequence YTRFSLARQV containing basic amino acids within the cytosoloic domain of TfR represented the binding domain of hsc7042. However, when inhibitors of hsc70 were added to the binding assays, secretion of TfR was not affected indicating that TfR/hsc70 interactions were not the signal for sorting of TfR into exosomes. Rather, in these same studies, Alix a well-known protein involved in the biogenesis of exosomes from other cells, was also shown to interact with the YTRF motif suggesting a contribution to TfR exosomal sorting. In addition, it was shown that sorting of TfR was concomitant with proteosomal degradation of abundant cytosolic proteins via AP2 complexes.

Our MS analysis revealed the presence of TfR, including the sequence YTRFSLARQV, hsc71 protein (another name for hsc70) and Alix whereas abundant cytosolic proteins were absent. It therefore seems that similar mechanisms operate in the biogenesis and sorting of human reticulocyte-derived exosomes excepting for Tsg101 which is not present in human reticulocytes15 neither in our analysis. Last, Galectin 5 is a rat-specific protein involved in an ESCRT-independent sorting pathway of some glycosylated proteins43. We identified Galectin 3 binding protein in our dataset. Whether it has a similar function as Galectin 5 remains to be determined.

Reticulocyte-derived exosomes from experimental infections of mice with a reticulocyte-prone rodent malaria parasite contain parasite antigens and MHC class-I molecules12. Moreover, when used in immunizations, they were able to confer full and long-lasting protection upon lethal challenges as well as eliciting effector memory T cells11. Noticeably, we identified HLA class-I antigens in HuRex and our own unpublished results have also identified HLA class-I antigens and parasites antigens in plasma-derived exosomes from malaria patients. Elegant studies on the mechanism of antigen-specific T cell stimulation by peptide-bearing exosomes demonstrated activation of T cell proliferation mainly in the presence of mature dendritic cells44. We thus used a functional assay38 to demonstrate the potential capacity of HuRex to interact with dendritic cells as they play a pivotal role in antigen presentation in natural malarial human infections45. This assay previously demonstrated that ganglioside-containing vesicles such as viral-like particles or exosomes could be captured by mature dendritic cells expressing Siglec-139. Noticeably, our results demonstrated Siglec-1-dependent specific capture of HuRex by mDCs as well as co-localization of HuRex with VLPs (Fig. 4). These data suggest that in addition of a “garbage-disposal” mechanism for the terminal differentiation of reticulocyte to erythrocytes, HuRex can facilitate antigen presentation via dendritic cells in the context of a human infection with a unique tropism for reticulocytes.

Studies on the role of extracellular vesicles, including exosomes, in red cell diseases are just beginning but already promise to shed light into mechanistic insights of pathology and in identifying non-invasive biomarkers46. For instance, in sickle cell disease (SCD), a group of inherited cell disorders, as well as in thalassemias, characterized by abnormal haemoglobin production, studies on the levels of platelets and red blood cells microparticles revealed an elevated level as opposed to normal individuals47,48. Moreover, a casuistic association on the abnormal presence of α4β1 integrin in circulating red blood cells leading to vascular obstruction in patients with SCD has been observed49. Human malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax, a parasite with a unique tropism for reticulocytes, is a red cell disease inducing inducing hemolytic anemia upon infections50. Knowledge on this parasite and disease have been hampered due to the lack of a continuous in vitro culture system. Our data shows that several receptors and proteins involved in entrance of the parasite into the host cell, such as CD9851, CD7152, band 353 and erythrocyte band 754, are selectively removed in HuRex. Remarkably, a recent report provides the first direct evidence of the role of exosomes in erythroid diseases. It was shown that the S100-A9 protein associated to exosomes represent a new pathway for NF-κβ activation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells34. In addition, extracellular vesicles in hematological malignancies have been stood out not only as promoters of tumor aggressiveness, but also as a valuable source of biomarkers for diagnosis55. Further studies on extracellular vesicles, including HuRex, in the context of red cell diseases are warranted.

In conclusion, this work opens new avenues for furthering studies of human reticulocyte-derived exosomes: firstly, on their biogenesis as most of the data presently available on this subject are from other species; secondly, on the possibility that HuRex can present pathogen-peptide antiges via dendritic cells inducing T cell responses; thirdly, on guiding new approaches to develop a continuous in vitro culture system for P. vivax; fourthly, on comparative analysis of the molecular composition of reticulocyte-derived exosomes from plasma or other body fluids in patients with difficulty to diagnose red cell diseases thus providing an alternative for identifying novel biomarkers. Last but not least, as quoted elsewhere8, perhaps Rose Johnstone was right: after having been a curiosity for many years, we might be at the doorstep of recognizing the potential of reticulocyte-derived exosomes.

Materials and Methods

Purification of human reticulocytes

Human cord blood samples were obtained from the Blood and Tissue Bank of Barcelona (https://www.bancsang.net/) in accordance with the Good Clinical and Laboratory Practice Guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and local rules and national regulations. The protocol, including the informed consent forms, has been approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Vall d’Hebron University Hospital (PR(CS)236/2017). Briefly, similarly to a previous work56, 70 mL of cord blood were centrifuged at 1000 g for 15 min. After removal of plasma, the pelleted cells were washed and re-suspended at 50% hematocrit with RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma). Leukocytes and platelets were removed by filtration through columns of cellulose powder (Whatman), previously packed with 10 mL of cellulose, irradiated with ultraviolet light for sterilization and washed with a double volume of RPMI medium immediately before their use. Filtrated blood was washed twice with RPMI medium and adjusted to 50% hematocrit. 5 mL aliquots of blood were carefully layered on 6 mL 70% Percoll (Healthcare). After centrifugation at 1200 g for 15 min at 20 °C, concentrated reticulocytes in the Percoll interface were carefully collected and washed twice with RPMI medium. Reticulocyte quantification was performed by examination of brilliant cresyl blue (BCB)/Giemsa stained thin blood films57. Only samples with >20% reticulocyte-enrichments and <2% leukocytes were used for HuRex production. We routinely obtained in the order of 108 reticulocytes per 70 mL of cord blood.

In vitro production and isolation of human reticulocyte-derived exosomes

Reticulocytes were cultured for 36 h at 37 °C and 1–3% hematocrit in RPMI medium, not supplemented or supplemented with 0.5% of human AB serum, previously depleted of exogenous exosomes. Viability of reticulocytes was assessed using Trypan Blue stain 0.4% (Sigma, 93595). Cell-free post-culture supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 1,300 g for 20 min at 20 °C. To isolate Rex, 2 mL of culture supernatants were loaded on 10 mL-sepharose CL-2B (Sigma) size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) columns26, where fractions of 500 µL were collected. Alternatively, 6–10 mL of culture supernatants were subjected to sequential centrifugation at 4 °C for 15,000 g/45 min and UC at 100,000 g/90 min25, where exosome pellets were resuspended in 200 µL of PBS. Protein content of SEC fractions and UC samples was determined by Nanodrop® ND-1000 and BCA assay (Thermo Scientific).

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA)

Size distribution and concentration of exosomes were determined by NTA using a NanoSight LM10 instrument (Malvern Instruments Ltd) as described26. Data were analyzed with NTA software (version 3.1).

Bead-based flow cytometry

SEC fractions enriched in exosomes were identified by bead-based flow cytometry25,26 assessing the presence of the transferrin receptor, CD71, a major component of Rex4,5,8. UC samples were similarly analyzed to warrant the presence of this marker. Briefly, SEC fractions and UC samples were coupled to 4 µm-aldehyde/sulfate-latex beads (Invitrogen) for 15 min at RT. Beads were then resuspended in 1 mL of bead-coupling buffer (BCB: PBS with 0.1% BSA and 0.01% NaN3) and incubated overnight at RT on rotation. Exosome-coated beads were then centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 min at RT, and washed once with BCB prior to incubation with anti-CD71 (ab84036) at 1:1,000 dilution for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing with BCB, exosome-coated beads were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen, A-11008) at 1:100 dilution. Coated beads incubated with secondary antibodies were used as a control. Labelled exosome-beads were washed twice with BCB before being finally resuspended in PBS and subjected to flow cytometry (FacsVerse; BD). Flow Jo software was used to compare mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of exosome-coated beads.

Immunoblot analysis

Ten µL aliquots of either a UC preparation or individual SEC fractions were analyzed by Western blot against human CD71. Membranes were probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-CD71 (ab84036) at 1:250 dilution for 1 hour at RT. A goat anti-rabbit IgG coupled to HRP (Sigma, A6154) was used at a dilution of 1:2,500 for 1 hour at RT. Revealing was performed using ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Pierce™) in ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Additionally, 20 µL aliquots of UC preparations were analyzed to confirm the presence of HSP70, GAPDH and stomatin in HuRex. Membranes were incubated for 1 hour at RT with primary antibodies anti-HSP70 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, W27 sc-24) at 1:250 dilution, anti-GAPDH (Sigma, G9545) at 1:500 dilution or anti-stomatin (Invitrogen, PA5-30019) at 1:250 dilution. Subsequently, membranes were washed and incubated for 1 h at RT with the Li-Cor IRDye-labeled secondary antibodies IRDye® 800CW goat-anti-mouse (925-32210, Li-Cor Biosciences) at 1:15,000 dilution or IRDye® 680RD goat anti-rabbit (925-68021, Li-Cor Biosciences) at 1:20,000 dilution. Blots were analyzed with the Odyssey near-infrared system (Li-Cor Biosciences) having the intensity of 700 channel set up at 5 and the one of 800 channel at 7. Images were edited using the software Image J (NIH).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

TEM was performed over HuRex UC preparations negatively stained as previously detailed12. Preparations were analyzed with a Jeol JEM-1100 TEM (Jeol Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Gatan Ultrascan ES1000 CCD Camera. Immunogold labeling was performed as detailed elsewhere26 with anti-CD71 (ab84036).

HuRexDiI generation

Reticulocyte-enriched RBCs were labeled with DiI (Molecular Probes, V-22885) following manufacturer’s instructions. Culture of stained cells and exosome isolation was performed as for the unstained HuRex. Fluorescence of HuRexDiI was determined by a Fluoroskan Ascent FL fluorimeter (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Exosome and VLP capture by mature monocyte-derived DCs via Siglec-1

2 × 105 LPS-matured monocyte-derived DCs (mDCs) were obtained as previously described38 and incubated with 50 μg HuRexDiI at 37 °C for 4 hours. Cells were washed and acquired with a BD FACSCalibur™ cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software. For microscopy analysis, mDCs were pulsed for 24 h with HuRexDiI and then with 150 μg of fluorescent viral-like particles containing Gag-enhanced green fluorescent (VLPHIV-Gag-eGFP) for 3 additional hours at 37 °C. Cells were washed, fixed, cytospun into coverslips, mounted with DAPI mounting media (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed with an Ultraview ERS Spinning Disk System (Perkin-Elmer) mounted on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M inverted microscope. Volocity software (Perkin-Elmer) was used to analyze microscopy images.

To determine whether Siglec-1 could represent a receptor for entrance of HuRex, mDCs were pre-incubated with 10 µg/mL of an anti-Siglec-1 monoclonal antibody (clone 7–239; Abcam) or a mouse anti-human IgG1 isotype control (BD) at RT for 15 min39 before addition of 50 μg HuRexDiI at 37 °C for 4 hours. Capture was analyzed by flow cytometry as described above.

Mass spectrometry

Liquid chromatography (nanoLCULTRA-EKSIGENT) followed by mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) on a LTQ Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was performed following our own procedures26. To increase exosomal protein coverage, some samples (CB30_PS_SEC; CB30_PS_UC; CB31_AS_SEC; CB31_AS_UC) were extracted with RIPA buffer and digested with Lys-C in addition to Trypsin digestions.

Protein identification and in silico analysis

Mass spectrometry data were processed by Mascot v2.5.1 (Matrix Science) using the human sequences from the UniProt-Swiss-prot database (release April 2017) with a false-discovery rate below 1%. Proteins identified by a unique peptide were only accepted if present in two or more samples. Keratins and keratin-associated proteins as well as potential serum contaminants were removed from the final list of proteins (Supplementary Table S1). We considered as serum contaminants the classical plasma proteins described by Anderson and Anderson proteomics58 as well as other protein components compiled in this work that were exclusively detected in HuRex preparations from serum-supplemented cultures. The MS proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD00854559.

We estimated relative protein abundance calculating the normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF) as described elsewhere36. This protein quantification index was established considering all proteins identified prior to filtering with their corresponding number of peptide spectrum matches.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eva Borrás and Eduard Sabidó from the CRG/UPF Proteomics Unit, Josep Maria Estanyol and María José Fidalgo from the Proteomics Unit of the Scientific and Technological Centers, Universitat de Barcelona (CCiTUB), Pablo Castro and Alejandro Sánchez from the Microscopy Facility at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and Marco A. Fernández from the Flow Cytometry Unit, IGTP. We are also grateful to Martyna Filipska and Dr. Rafael Rosell (IGTP) for the kind donation of the anti-HSP70 antibody. MDV is a predoctoral fellow supported by Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Creixement, Generalitat de Catalunya (2017 FI_B2_00029). AMN was recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from CNPq, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Brasil. ISGlobal and IGTP are members of the CERCA Programme, Generalitat de Catalunya. Work in the group of JMP and NIU is supported by the Spanish Secretariat for Research through grant SAF2016-80033-R, which also supports the pre-doctoral fellowship of DPZ (BES-2014-069931). Work in the laboratory of HDP and CFB is funded by the Ministerio Español de Economía y Competitividad (SAF2016-80655-R) and by the Network of Excellency in Research and Innovation on Exosomes (REDiEX) (SAF2015-71231-REDT). This work received specific support from the Fundación Ramón Areces, 2014. “Investigación en Ciencias de la Vida y de la Materia”, Project “Exosomas: Nuevos comunicadores intercelulares y su aplicabilidad como agentes terapéuticos en enfermedades parasitarias desatendidas”.

Author Contributions

M.D.V., D.P.Z., A.G.V. and J.S.B. performed experiments. M.D.V., A.M.N., D.P.Z., A.G.V., N.I.U., J.M.P., C.F.B. and H.P. suggested experiments and analyzed the data. M.D.V., N.I.U., C.F.B. and H.P. drafted the manuscript. All the authors revised the manuscript and consented to its publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Carmen Fernández-Becerra, Email: carmen.fernandez@isglobal.org.

Hernando A. del Portillo, Email: hernandoa.delportillo@isglobal.org

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-32386-2.

References

- 1.Yáñez-Mó M, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaput N, Théry C. Exosomes: immune properties and potential clinical implementations. Semin. Immunopathol. 2011;33:419–40. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin J, et al. Exosomes: novel biomarkers for clinical diagnosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2015;2015:657086. doi: 10.1155/2015/657086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan BT, Johnstone RM. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: selective externalization of the receptor. Cell. 1983;33:967–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harding C, Heuser J, Stahl P. Receptor-mediated Endocytosis of Transferrin and Recycling of the Transferrin Receptor in Rat Reticulocytes Biochemical Approaches to Transferrin. J Cell Biol. 1983;97(2):329–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnstone RM, Adam M, Hammonds JR, Turbide C. Vesicle Formation during Reticulocyte Maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:9412–9420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanc L, Vidal M. Reticulocyte membrane remodeling: contribution of the exosome pathway. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2010;17:177–83. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328337b4e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vidal M. Exosomes in erythropoiesis. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2010;17:131–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rieu S, Geminard C, Rabesandratana H, Sainte-Marie J, Vidal M. Exosomes released during reticulocyte maturation bind to fibronectin via integrin α4β1. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:583–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carayon K, et al. Proteolipidic composition of exosomes changes during reticulocyte maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:34426–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.257444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martín-Jaular L, et al. Spleen-Dependent Immune Protection Elicited by CpG Adjuvanted Reticulocyte-Derived Exosomes from Malaria Infection Is Associated with Changes in T cell Subsets’ Distribution. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016;4:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin-Jaular L, Nakayasu ES, Ferrer M, Almeida IC, Del Portillo HA. Exosomes from Plasmodium yoelii-infected reticulocytes protect mice from lethal infections. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabesandratana H, Toutant JP, Reggio H, Vidal M. Decay-accelerating factor (CD55) and membrane inhibitor of reactive lysis (CD59) are released within exosomes during In vitro maturation of reticulocytes. Blood. 1998;91:2573–2580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Gassart A, Geminard C, Fevrier B, Raposo G, Vidal M. Lipid raft – associated protein sorting in exosomes. Blood. 2003;102:4336–4344. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gautier EF, et al. Comprehensive Proteomic Analysis of Human Erythropoiesis. Cell Rep. 2016;16:1470–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu, T. T. T. et al. Quantitative mass spectrometry of human reticulocytes reveal proteome-wide modifications during maturation. Br. J. Haematol, 10.1111/bjh.14976 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Wilson MC, et al. Comparison of the Proteome of Adult and Cord Erythroid Cells, and Changes in the Proteome Following Reticulocyte Maturation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2016;15:1938–46. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.057315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasini EME, et al. In-depth analysis of the membrane and cytosolic proteome of red blood cells. Blood. 2006;108:791–801. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-007799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Alessandro A, Dzieciatkowska M, Nemkov T, Hansen KC. Red blood cell proteomics update: Is there more to discover? Blood Transfus. 2017;15:182–187. doi: 10.2450/2017.0293-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryk AH, Wiśniewski JR. Quantitative Analysis of Human Red Blood Cell Proteome. J. Proteome Res. 2017;16:2752–2761. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanc L, et al. The water channel aquaporin-1 partitions into exosomes during reticulocyte maturation: Implication for the regulation of cell volume. Blood. 2009;114:3928–3934. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-230086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malleret, B. et al. Significant Biochemical, Biophysical and Metabolic Diversity in Circulating Human Cord Blood Reticulocytes. PLoS One8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Li J, et al. Serum-free culture alters the quantity and protein composition of neuroblastoma-derived extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2015;4:26883. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.26883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abramowicz, A., Widlak, P. & Pietrowska, M. Molecular BioSystems Proteomic analysis of exosomal cargo: the challenge of high purity vesicle isolation. Mol. Biosyst. 17–19, 10.1039/C6MB00082G (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Théry, C., Amigorena, S., Raposo, G. & Clayton, A. Isolation and Characterization of Exosomes from Cell Culture Supernatants and Biological Fluids. In Current Protocols in Cell Biology30, 3.22.1–3.22.29 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.de Menezes-Neto A, et al. Size-exclusion chromatography as a stand-alone methodology identifies novel markers in mass spectrometry analyses of plasma-derived vesicles from. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2015;1:1–14. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lötvall J, et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: A position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2014;3:1–6. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Pol, E. et al. Particle size distribution of exosomes and microvesicles by transmission electron microscopy, flow cytometry, nanoparticle tracking analysis, and resistive pulse sensing. J. Thromb. Haemost, 10.1111/jth.12602 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Géminard C, Nault F, Johnstone RM, Vidal M. Characteristics of the Interaction between Hsc70 and the Transferrin Receptor in Exosomes Released during Reticulocyte Maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:9910–9916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalra H, et al. Vesiclepedia: A Compendium for Extracellular Vesicles with Continuous Community Annotation. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai IH, Murthy SN, Steck TL. Effect of red cell membrane binding on the catalytic activity of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:1438–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanc L, Vidal M. New insights into the function of Rab GTPases in the context of exosomal secretion. Small GTPases. 2017;0:1–12. doi: 10.1080/21541248.2016.1264352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donato R, et al. Functions of S100 proteins. Curr. Mol. Med. 2013;13:24–57. doi: 10.2174/156652413804486214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prieto D, et al. S100-A9 protein in exosomes from chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells promotes NF-κB activity during disease progression. Blood. 2017;130:777–788. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-02-769851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C. Biogenesis, Secretion, and Intercellular Interactions of Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014;30:255–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paoletti AC, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of distinct mammalian Mediator complexes using normalized spectral abundance factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:18928–18933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606379103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nahnsen S, Bielow C, Reinert K, Kohlbacher O. Tools for Label-free Peptide Quantification <sup/>. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2013;12:549–556. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R112.025163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Izquierdo-Useros N, et al. Capture and transfer of HIV-1 particles by mature dendritic cells converges with the exosome-dissemination pathway. Blood. 2009;113:2732–2741. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Izquierdo-Useros, N. et al. Siglec-1 Is a Novel Dendritic Cell Receptor That Mediates HIV-1 Trans-Infection Through Recognition of Viral Membrane Gangliosides. PLoS Biol. 10 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vidal M, Mangeat P, Hoekstra D. Aggregation reroutes molecules from a recycling to a vesicle-mediated secretion pathway during reticulocyte maturation. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 16):1867–77. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.16.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Géminard C, de Gassart A, Blanc L, Vidal M. Degradation of AP2 during reticulocyte maturation enhances binding of hsc70 and Alix to a common site on TfR for sorting in exosomes. Traffic. 2004;5:181–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.0167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barrès C, et al. Galectin-5 is bound onto the surface of rat reticulocyte exosomes and modulates vesicle uptake by macrophages. Blood. 2010;115:696–705. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Théry C, et al. Indirect activation of naïve CD4+ T cells by dendritic cell–derived exosomes. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:1156–1162. doi: 10.1038/ni854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amorim KN, Chagas DC, Sulczewski FB, Boscardin SB. Dendritic Cells and Their Multiple Roles during Malaria Infection. J. Immunol. Res. 2016;2016:2926436. doi: 10.1155/2016/2926436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hebbel RP, Key NS. Microparticles in sickle cell anaemia: promise and pitfalls. Br. J. Haematol. 2016;174:16–29. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aharon A, Rebibo-Sabbah A, Tzoran I, Levin C. Extracellular vesicles in hematological disorders. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2014;5:e0032. doi: 10.5041/RMMJ.10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Habib A, et al. Elevated levels of circulating procoagulant microparticles in patients with -thalassemia intermedia. Haematologica. 2008;93:941–942. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brittain JE, Parise LV. The α4β1 integrin in sickle cell disease. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2008;15:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mueller I, et al. Key gaps in the knowledge of Plasmodium vivax, a neglected human malaria parasite. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2009;9:555–66. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70177-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malleret, B. et al. CD98 is a Plasmodium vivax receptor for human reticulocytes. In Proceedings of International Conference on Plasmodium vivax 2017 ISSN: 2527–0737 1, #63834 (2017).

- 52.Gruszczyk J, et al. Transferrin receptor 1 is a reticulocyte-specific receptor for Plasmodium vivax. Science. 2018;359:48–55. doi: 10.1126/science.aan1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alam, M. S., Zeeshan, M., Rathore, S. & Sharma, Y. D. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications Multiple Plasmodium vivax proteins of Pv-fam-a family interact with human erythrocyte receptor Band 3 and have a role in red cell invasion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 6–11, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.096 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Hiller NL, Akompong T, Morrow JS, Holder AA, Haldar K. Identification of a Stomatin Orthologue in Vacuoles Induced in Human Erythrocytes by Malaria Parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:48413–48421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caivano, A. et al. Extracellular vesicles in hematological malignancies: From biology to therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Russell B, et al. A reliable ex vivo invasion assay of human reticulocytes by Plasmodium vivax. Blood. 2011;118:e74–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor-Robinson AW, Phillips RS. Predominance of infected reticulocytes in the peripheral blood of CD4+ T-cell-depleted mice chronically infected with Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi. Parasitol. Res. 1994;80:614–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00933011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson NL, Anderson NG. The Human Plasma Proteome. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2002;1:845–867. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R200007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deutsch EW, et al. The ProteomeXchange consortium in 2017: supporting the cultural change in proteomics public data deposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D1100–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.