Abstract

Background

General practice in the UK is experiencing a workforce crisis. However, it is unknown what impact prescribing support teams may have on freeing up GP capacity and time for clinical activities.

Aim

To release GP time by providing additional prescribing resources to support general practices between April 2016 and March 2017.

Design and setting

Prospective observational cohort study in 16 urban general practices that comprise Inverclyde Health and Social Care Partnership in Scotland.

Method

GPs recorded the time they spent dealing with special requests, immediate discharges, outpatient requests, and other prescribing issues for 2 weeks prior to the study and for two equivalent periods during the study. Specialist clinical pharmacists performed these key prescribing activities to release GP time and Read coded their activities. GP and practice staff were surveyed to assess their expectations at baseline and their experiences during the final data-collection period. Prescribing support staff were also surveyed during the study period.

Results

GP time spent on key prescribing activities significantly reduced by 51% (79 hours, P<0.001) per week, equating to 4.9 hours (95% confidence interval = 3.4 to 6.4) per week per practice. The additional clinical pharmacist resource was well received and appreciated by GPs and practices. As well as freeing up GP capacity, practices and practitioners also identified improvements in patient safety, positive effects on staff morale, and reductions in stress. Prescribing support staff also indicated that the initiative had a positive impact on job satisfaction and was considered sustainable, although practice expectations and time constraints created new challenges.

Conclusion

Specialist clinical pharmacists are safe and effective in supporting GPs and practices with key prescribing activities in order to directly free GP capacity. However, further work is required to assess the impact of such service developments on prescribing cost-efficiency and clinical pharmacist medication review work.

Keywords: general practice, pharmacists, prescribing support, primary care, service development

INTRODUCTION

In the UK, there is currently a workforce crisis in general practice. In part, this is being driven by an ageing population with greater multimorbidity,1 along with successive UK government policies to transfer more and more patient care to primary care. These policies are causing large increases in workload2 and pressures that compromise patient-centred care, diminishing GPs’ job satisfaction and health.3 There is also a need to redress these pressures; to enable a better work–life balance to allow GPs to fulfil personal responsibilities and needs.4,5 All of this is driving general practice staff away from the NHS, away from their professions, and away from patients.3,6

Specially trained clinical pharmacists and prescribing support teams have worked with general practices for more than two decades to support GPs and practices, primary care services, and patients. In the UK, this work has involved:

patient-level face-to-face polypharmacy medication reviews;7,8

patient identification and treatment optimisation for those with long-term conditions;8–10

prescriber education;11

tackling difficult areas of prescribing as non-medical prescribers (that is, prescribers who are not doctors);12,13 and

prescribing cost containment and reduction.14

Similar initiatives have evolved in North America and Australia.8,15,16 In the main, UK prescribing teams predominantly consist of specialist clinical pharmacists and pharmacy technicians; however, there are large variations in where, how, and what services are provided. In part, this is due to differences in funding models, local and national agendas, and pressures on current systems and services.

In 2015, the Scottish Government announced the details of the Primary Care Fund, which would involve investment of £50 million over 3 years,17 to support primary care services, including GPs, and improve patient access to primary care services. Over 3 years, £20.5 million was allocated to the Primary Care Transformation Fund, including the New Ways of Working (nWOW) test of change programme, to address existing demand.17W Across Scotland, some of the money was committed to recruiting up to 140 whole-time equivalent additional pharmacists with advanced clinical skills training, or those undertaking the training, to support the care of patients with long-term conditions and free up GP capacity and time.17 England and Wales subsequently announced similar commitments.18 However, it is not known what direct impact prescribing support teams have on freeing up GP capacity and time.

How this fits in

General practice and primary care are experiencing difficulties coping with demand. There are medical and political expectations that specialist clinical pharmacists and non-medical prescribers can be employed to release GP time and capacity, but information is lacking regarding the effect of these health professionals on primary care. This study demonstrates that they can free up direct GP time and GP capacity, and that the effects on staff morale and patient safety can be positive.

The aim of the service development presented here was to release GP time by providing additional prescribing resources to support general practices.

METHOD

Study design

This prospective observational cohort study assessed service development from April 2016 until March 2017.

Setting

The UK’s NHS is taxpayer funded and devolved in the home nations; the NHS in Scotland is distinct from the other home nations, both in management and policy. NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (NHSGGC) provides healthcare services for a diverse population of 1.2 million people across a varied urban region containing 260 general practices. Inverclyde Health and Social Care Partnership (HSCP) is one of six HSCPs within NHSGGC and serves a population of 82 000 people across a highly urbanised and deprived area of Scotland. The HSCP brings together community primary care health services and social work services to support patients in the locality.

Inverclyde HSCP has 16 general practices, 12 of which are Deep End practices serving the most socioeconomically deprived populations in Scotland.19 The 16 practices are served by 69 GPs (54% female); this comprises a median of 4 (range 1–7) GPs with 4239 (1895–9426) registered patients per practice. Of these patients, 19% (15 547) are older adults (aged ≥65 years) with a higher proportion being care home residents than the NHSGGC HSCP average (1% versus 0.8%). In addition, there is a greater prevalence of commonly recorded long-term conditions — as measured by the Quality and Outcomes Framework — than in other areas of Scotland;20 these are associated with higher prescribing costs per patient.

Since 2001, the HSCP prescribing team has worked collaboratively in partnership with GPs and practices. It provides pharmacist-led, face-to-face patient polypharmacy review clinics within practices and care homes, thereby optimising appropriate medicines for a variety of conditions (for example, pain and cardiovascular conditions), as well as reducing or stopping inappropriate medicines, achieving local and national prescribing indicators, and optimising safety, quality, and cost-effective prescribing.21 In early 2016, prior to starting the GP capacity-freeing work, practices were invited to participate in the study and outline how they would use additional pharmacy support. Subsequently, the HSCP lead clinical pharmacist met with practices individually to develop practice agreements, objectives, work plans, and timetables regarding how the additional resource would be used.

Since April 2016, Inverclyde HSCP has piloted nWOW, thereby developing transformational change and multidisciplinary working. It provides additional resources to general practices and informs the new General Medical Services (GMS) Contract in Scotland. The nWOW pharmacy pilot set out to improve patients’ care through greater use of pharmacist and pharmacy technician skills, further developing work outlined above, as well as directly releasing GP capacity. Pharmacists were also involved in the national pilot for electronic prescribing for pharmacist independent prescribers, enabling prescriptions to be processed more efficiently. In order to develop nWOW, new pharmacists and technicians were recruited, completed NHSGGC’s induction, and started NHS Education for Scotland general practice training.22 The new, expanded team continued face-to-face patient-level medicines review clinics, achieving national and local prescribing indicators, and undertaking cost-efficiency work, with 50% (225 hours) of pharmacist time committed to directly freeing up GP capacity.

Patients and intervention

As this work involved service development, all patients registered with a general medical practice within the HSCP had the potential to be included if their case involved one or more of four prescribing activities, which were agreed and targeted in order to release GP time and use the clinical pharmacists most effectively. The four prescribing activities were:

special requests — acute prescriptions created and issued by a GP without an appointment, such as a recently started new medicine, antidepressant course for a first episode of depression, or where potential concordance or safety issues required ongoing monitoring;

immediate discharges — letters or documents containing patient discharge information from an inpatient admission; this activity also involved ensuring medicines were clinically reviewed and accurately reconciled, and systems for practice prescribing and monitoring (for example, checking blood results) were accurately updated;

outpatient requests — requests for a GP to prescribe medicine(s) initiated or recommended by specialist outpatient clinics;

other medicines issues — these were defined as medicines shortages due to manufacturing and/or supply issues, practice medicines information, and community pharmacy queries.

For all of the above activities a medicines clinical review was carried out, where appropriate. Interface issues were addressed and patients and/or carers were contacted to ensure prescribing was safe and appropriate before prescriptions were issued.

Data collection and handling

GPs used a standardised paper audit form (available from the authors on request) to self-record and report the time taken to address special requests, immediate discharges, outpatient requests, and other medicines issues during three distinct 2-week audit periods, namely, at baseline (April–May 2016) prior to work starting, in autumn (September–October 2016), and again in spring (January–February 2017). These audit times were specifically chosen to avoid holiday periods, which are known to influence prescribing volumes and general practice workloads. During the study period, pharmacists Read coded their activities using a standardised template embedded in practice prescribing systems. Six months into the initiative prescribing support team members were also surveyed (September 2016) with staff being contacted by their line manager.

GPs and practice staff were surveyed twice so their opinions could be captured. This was done first at baseline to ascertain their expectations, and then the following spring to find out about their experiences. Specifically designed and tested, self-administered, short (≤5 minutes to complete) standardised electronic questionnaires (via the online tool WebRopol) were used, with multiple-choice questions and free-text boxes (available from the authors on request). The second survey was specifically designed to draw out key benefits and concerns from nWOW. Surveys were emailed to all practice staff, via their practice managers, to complete. Prescribing support staff based in practices gave their practices reminders after the 2-week deadline.

GP audit forms were returned to the prescribing team administrator, who collated practice-level data using Microsoft Excel. Data were further analysed using SPSS (version 23). GP prescribing activity times were analysed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and, due to the small number of practices, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to assess for co-relation between time change achieved and practice characteristics. Read-coded prescribing activity was electronically extracted from practice systems. Survey data were collated electronically and analysed.

RESULTS

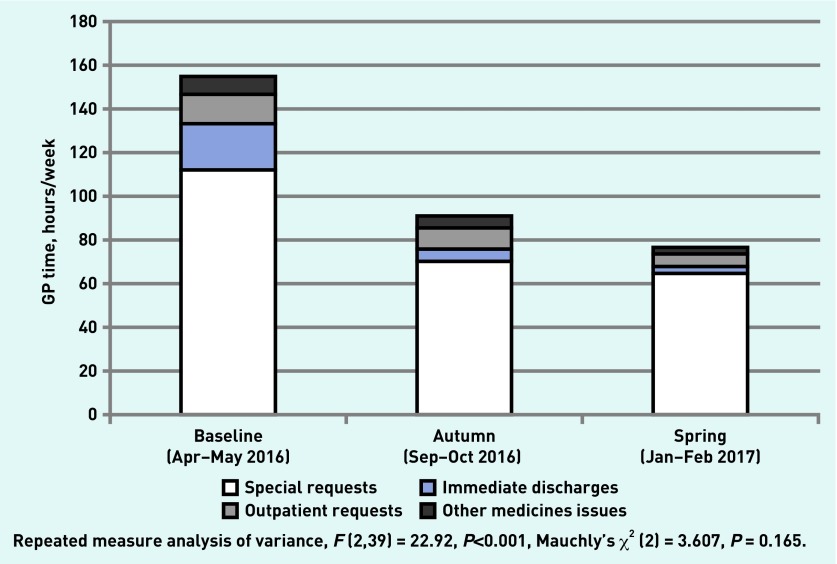

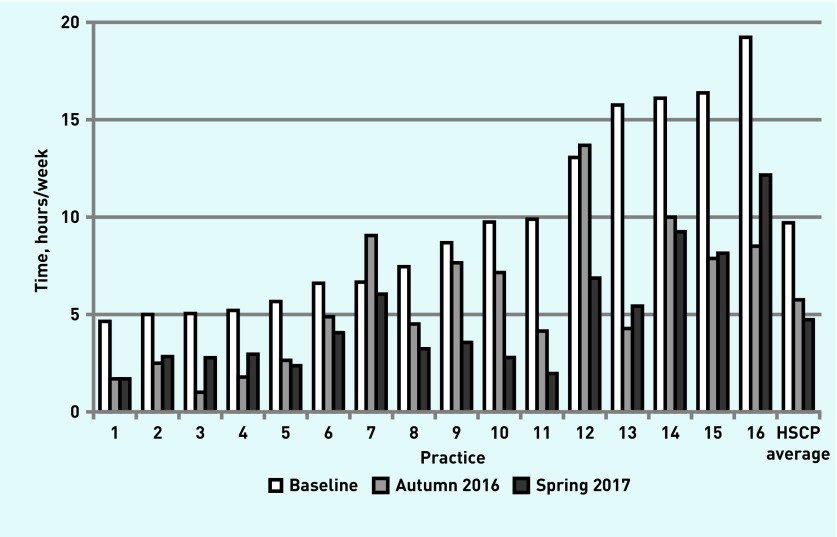

The characteristics of the prescribing team are outlined in Table 1. Additional prescribing support resources achieved a statistically significant 51% (79 hours per week, F (2,39) = 22.92, P<0.001) reduction in practice-level time that GPs spent on prescribing activities across the HSCP (Figure 1); this equates to a mean of 4.9 hours (95% confidence interval [CI] = 3.4 to 6.4) per practice per week (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the prescribing support team (pharmacists and pharmacy technicians)

| Pre-2016, n= 12a | New staff from 2016, n= 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median (range) | 40 (29–61) | 33 (28–50) |

|

| ||

| Sex: female (%) | 11 (92) | 8 (80) |

|

| ||

| Years since qualified, median (range) | 17 (7–39) | 9 (6–26) |

|

| ||

| Years working in general practice, median (range) | 9 (3–17) | 0 |

|

| ||

| Previous experience working in: | ||

| Community pharmacy only | 6 | 8 |

| Hospital pharmacy only | 3 | 1 |

| Community and hospital | 3 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Staff with extra postgraduate qualifications, n (%)b | 9 (75) | 3 (30) |

|

| ||

| Non-medical prescribers, n (%)c | 10 (100) | 3 (43) |

Pre-2016 staffing hours equated to four whole-time equivalent (WTE) pharmacists, two WTE pharmacy technicians, one WTE administration assistant, and one WTE lead clinical pharmacist. It was expanded to include an additional eight WTE pharmacists and two WTE pharmacy technicians for 2016–2017.

Advanced clinical training skills: clinical pharmacy or prescribing sciences postgraduate studies from certificate to Masters level, and beyond.

Ten pre-2016 and seven new pharmacists respectively.

Figure 1.

Total GP time spent addressing key prescribing activities, by audit period.

Figure 2.

GP hours per week spent addressing prescribing activities, by practice. HSCP = Health and Social Care Partnership.

There was a strong statistically significant correlation between practice size and practice-level GP time released (Pearson’s r = 0.671, 95% CI = 0.262 to 0.875, P = 0.004).

Of the 79 hours per week released, most were spent undertaking special requests (59% [47/79 hours]) and discharge prescriptions (23% [18/79 hours]).

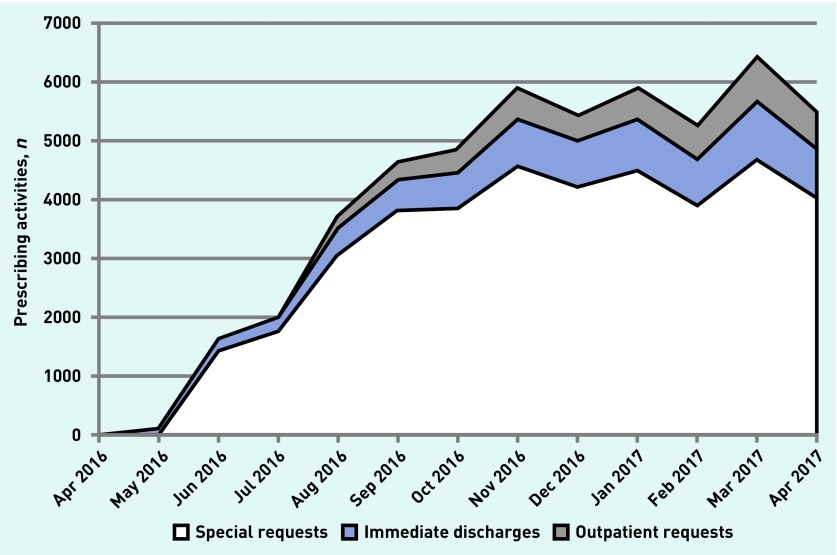

The time GPs spent addressing all four key prescribing activities was reduced (Figure 2), whereas completed Read-coded pharmacist prescribing activities, from the general practice electronic systems, increased (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Number of Read-coded pharmacist prescribing activities per calendar month.

Of the 210 HSCP general practice staff who could potentially complete the surveys, 17% (36/210) and 30% (63/210) completed a survey at baseline (‘expectation’) and the following spring (‘experience’) respectively (Table 2). The baseline survey indicated that 89% of staff were very positive and 11% were mostly positive about additional input. A minority (8%) were concerned that the initiative might increase their workload or create potential challenge:

‘Increased workload initially, with new team members being added to systems.’

(Practice manager, A2)

‘Less flexibility with prescribing and strict adherence to formulary, as sometimes knowledge of patient will influence decision.’

(GP, 27)

‘Patients may dislike pharmacist doing a role traditionally done by [a] GP — change of culture.’

(GP, 22)

Table 2.

Survey responses from GPs (n = 69), practice managers (n = 14), and other staff (n = 127)a

| Staff | Baseline survey, n (%) | Spring 2017 survey, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| GP | 18 (26) | 35 (51) |

|

| ||

| Practice manager | 10 (71) | 10 (71) |

| Otherb | 8 (6) | 18 (14) |

| Total | 36 | 63 |

Comprises 210 responders in total.

Other staff comprised 27 practice nurses, 13 healthcare assistants, and 87 practice staff (for example, reception or administrative staff). Data have been aggregated due to small cell sizes.

However, most responders were positive and supportive:

‘I see this as a very positive step forward in primary care for practices, patients, and pharmacists, whom I believe, as a profession, are underutilised in NHS Scotland.’

(GP, 9)

‘May slow down acute requests initially but I expect this to be a transient problem if it does arise.’

(GP, 70)

The survey conducted in spring 2017, when the initiative was under way, indicated an increase in GP capacity, reduced stress, and an improvement in morale, practice prescribing processes, and safety (for example, dose adjustments due to reduced renal function, and up-to-date blood monitoring for disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and others):

‘… pharmacists do not only help the GPs in the biggest way possible, they also help the practice nurse, offering prescribing advice. All of this just makes for a nicer, less-stressful day for everyone involved in the prescribing process for patients.’

(Practice manager, 22)

‘On medicines reconciliation, a more thorough, efficient process is now established, with detection and follow-up of inaccurate, and at times inappropriate, prescribing (from secondary care and primary care), which GPs would not necessarily detect. Overall, this has added to increasingly safe prescribing and saved GPs considerable time.’

(GP, 46)

‘Prior to the pilot I was considering leaving general practice as I had been feeling so burnt out and felt like I could not do my job safely. The pharmacist support has improved things greatly — while I still work extremely hard, I feel safer. Please continue this support.’

(GP, 4)

Some practices reported increasing some consultations to 15 minutes and one GP indicated having had time to take a tea break.

Overall, concerns regarding increased workload were not borne out as most (>90%) GP responders indicated that their workload did not increase. However, one GP highlighted an increase in workload when their pharmacist was sick or on annual leave:

‘Unintended consequences, workload increase for GP when pharmacist[s] are away, [on] annual leave/sick.’

(GP, 45)

In total, 80% (16/20) of the practice-based prescribing support team responded, of which 56% (9) were pre-2016 staff. The majority (87%) of pre-2016 and all new staff indicated that the nWOW changes were positive, enabling them to use more of their skills and expertise, and that they were comfortable and confident carrying out the activities; however, two colleagues were concerned about the levels of GP and practice expectations, and others raised issues regarding pressures of training new staff and time constraints. However, overall, 81% of responders considered the current workload to be sustainable:

‘In the practice in which my role has expanded most I have gained more increased job satisfaction as I have taken on more clinical roles and responsibilities, and have received positive feedback from the GPs within the practice.’

(Pre-2016 pharmacist, 3)

‘I feel GPs’ expectations of the team members I work with are very high. They expect them to take on too much for the limited time they have in practice.’

(New pharmacist, 10)

‘At present workload is difficult to balance due to expectations from GP and Prescribing Support Team. Unable to give much time to [prescribing] indicators, due to other work pressures, especially around training of new members of team and staff shortages within practices. Hopefully once new members of staff are fully trained work can be delegated appropriately and workload will be sustainable.’

(Pre-2016 pharmacist, 4)

DISCUSSION

Summary

The inclusion of additional specialist clinical pharmacists to perform key prescribing activities released an average of 5 hours’ direct GP time per practice per week; this is equivalent to one GP practice session per week. The additional pharmacy resource was well received and appreciated by general practice staff. However, as well as freeing up GP capacity, practices and practitioners identified positive effects on patient safety and staff morale, along with reductions in stress during the study period.

Strengths and limitations

Study strengths include addressing a real-world challenge in routine practice, freeing up system capacity and GP time, as well as demonstrating that this can be achieved. However, to the authors’ knowledge, a major strength of this study is that this is the first prospective study to demonstrate the impact of specialist clinical pharmacists and prescribing support teams directly freeing up system capacity and GP clinical time in routine practice. In part, this success has been achieved by building on previous clinical experience and relationships, and focusing on specific prescribing activities in which pharmacists can be effective, overcoming barriers previously identified in Canadian practice,23 such as lack of: a defined role, professional experience, training, and adequate resources. These barriers were overcome here by building on previous relationships, ensuring clarity of role, structured local and national training, as well as better resourcing of staff with tools to support their role such as electronic prescribing.

The study presented here also used a combination of data — subjective self-reporting by GPs, Read code activity, and survey data — to triangulate, assess, and demonstrate the impact and potential sustainability of specialist pharmacy services on routine practice. The relative simplicity of GPs’ self-recording and reporting of time taken on prescribing tasks was low impact and non-resource intensive; this enabled data capture without the need for conspicuous observational monitoring, which may have hampered or been impractical within clinical practice. Another strength is that the service development was carried out in a distinct HSCP in one region and — with additional local and national funding — had the flexibility to adapt general practice systems without imposing a preconceived standardised model of service delivery. In this way a ‘bottom-up’, flexible approach was encouraged.

The fact that this study was carried out in one region may be considered a limitation. However, there were large variations in the amount of practice-level GP time freed up from prescribing activities, with a positive correlation for more capacity being released in larger practices. Although findings may not be readily generalisable to other areas with different prescribing support resources and relationships, they may be of interest to others working in similar urban practices with similar staff and registered patient demographics.

As staff who were new to prescribing-support general practice work were employed, trained, and placed with practices during the study period, this may have limited — and possibly reduced — their overall impact on releasing capacity due to inexperience; however, significant changes were observed and, as they become more experienced, further gains may be achieved. Moreover, as pharmacists Read coded all activities for data extraction, this may have marginally reduced the freeing up of capacity. It should be noted that, as GPs are experiencing a variety of pressures and challenges,2,3,6 any help or additional resource may be welcomed and, therefore, influence their subjective self-reporting of the time taken to complete prescribing activities. However, the continuous increase in pharmacists’ Read-coded activity during the study period objectively demonstrated changes in practice.

Comparison with existing literature

Although there are comments and expectations regarding pharmacists freeing up GP time,17,24–25 and a variety of studies demonstrating the benefits of pharmacists working with practices and GPs,7–14 studies clearly demonstrating the freeing of GP time by pharmacists are lacking. Cochrane reviewers have also highlighted similar challenges in demonstrating the impact of primary care nursing services on GP workload.26 However, in contrast to previous studies, the current study has focused on specific routine practice prescribing activities rather than management of specific conditions or problematic areas of prescribing.7–14

Implications for research and practice

Enabling the direct release of GP capacity through additional specialist clinical pharmacist resources is a positive step towards integrated multidisciplinary working and patient care in general practice and primary care. However, there are a number of practice implications and challenges in developing and expanding nWOW models across the UK.

For >20 years, specialist clinical pharmacists have worked with general practices, GPs, and practice nurses to achieve improvements in patient care via clinical medication review and prescribing cost-efficiencies across the UK, North America, and Australasia.7–10,12,13,15,16 Maintaining these gains, and delivering nWOW and expanded pharmacist services, will be a challenge against a background of medicines shortages, large and sharp increases in drug prices, and funding constraints.27–29

As with other professions, challenges exist in recruiting pharmacists to general practices in rural areas. As community and hospital pharmacists move to general practice, this may have a negative impact on service delivery and patient safety in these areas. Due to a lack of practice pharmacist backfill, covering sickness, maternity, and annual leave may also limit continuity and delivery throughout the year.

Local and national training in Scotland will build national standards for the future but, at present, similar structures are less clear for other areas of the UK.

Some may consider pharmacists to be a cheaper option than GP prescribing. However, pharmacists take longer with prescribing as their core professional activities focus on safe, appropriate, and cost-effective medicine use. Therefore pharmacists may cost more in staffing terms to address similar prescribing issues, but reduce overall costs through better formulary compliance, improving prescribing systems, and patient safety.

Long-term secure funding is required to allow current gains to continue. These challenges are not insurmountable. In addition to directly releasing GP capacity, it is important to enable specialist clinical pharmacists to use their unique pharmaceutical care skillset to focus on individual patient-level prescribing issues — such as polypharmacy, complex medication reviews, realistic prescribing, and drug use7,8,10 — as well as advising and enabling other health professionals to tackle difficult prescribing issues12,13,15,16 in line with local and national objectives. This could help to minimise avoidable drug-related harms associated with avoidable hospital admissions.30–32 As such, it is important to understand how pharmacists contribute to complex patient care. The latest GMS contract in Scotland partially acknowledges this contribution as providing ‘additional’ advanced and specialist pharmacotherapy services,24 although these are core skills and activities that the authors consider essential to providing optimal patient care.

nWOW creates an opportunity to research, evidence, and publish the impact of additional prescribing support services in general practice. The direct impact on freeing up GP time must not be the only thing that is considered; the impact that different professions and multidisciplinary teams and models are having on hospital admission, long-term care, and, most importantly, the patients’ outcomes must also be taken into account.

Acknowledgments

With thanks to all patients, general practices, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Central Prescribing Support Team, Inverclyde Health and Social Care Partnership Prescribing Support Team, and staff for their work and support. Thanks to Maryann Dunnett and Colette Montgomery-Sardar for commenting on the manuscript.

Funding

The new Ways of Working intervention was funded by NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde and the Scottish Government, with £200 000 of Prescription for Excellence and £200 000 Primary Care Transformation Fund monies.

Ethical approval

Not required for this study.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobbs FDR, Bankhead C, Mukhtar T, et al. Clinical workload in UK primary care: a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England, 2007–14. Lancet. 2016;387(10035):2323–2330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doran N, Fox F, Rodham K, et al. Lost to the NHS: a mixed methods study of why GPs leave practice early in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2016 doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X683425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norman R, Hall JP. The desire and capability of Australian general practitioners to change their working hours. Med J Aust. 2014;200(7):399–402. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lachish S, Svirko E, Goldacre MJ, Lambert T. Factors associated with less-than-full-time working in medical practice: results of surveys of five cohorts of UK doctors, 10 years after graduation. Hum Resour Health. 2016;14(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12960-016-0162-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dale J, Potter R, Owen K, et al. Retaining the general practitioner workforce in England: what matters to GPs? A cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:140. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0363-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackie CA, Lawson DH, Campbell A, et al. A randomised controlled trial of medication review in patients receiving polypharmacy in a general practice setting. Pharm J. 1999;263:R7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan EC, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. Pharmacist services provided in general practice clinics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Admin Pharm. 2014;10(4):608–622. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spence D, Johnson C, Berry C, et al. Establishment of a disease register for patients with LVSD in primary care and comparison of current practice with evidence-based guidelines. Pharm J. 2002;268(7204):911–913. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowrie R, Mair FS, Greenlaw N, et al. Pharmacist intervention in primary care to improve outcomes in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(3):314–324. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowrie R, Lloyd SM, McConnachie A, Morrison J. A cluster randomised controlled trial of a pharmacist-led collaborative intervention to improve statin prescribing and attainment of cholesterol targets in primary care. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e113370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson C, Thomson A. Prescribing support pharmacists support appropriate benzodiazepine and Z-drug reduction 2008/09 — experiences from North Glasgow. Clin Pharm. 2010;3(Supp 1):S5–S6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson CF, Macdonald HJ, Atkinson P, et al. Reviewing long-term antidepressants can reduce drug burden: a prospective observational cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X658304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel B, Afghan S. Effects of an educational outreach campaign (IMPACT) on depression management delivered to general practitioners in one primary care trust. Ment Health Fam Med. 2010;6(3):155–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorensen L, Stokes JA, Purdie DM, et al. Medication reviews in the community: results of a randomized, controlled effectiveness trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58(6):648–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeve JF, Peterson GM, Rumble RH, Jaffrey R. Programme to improve the use of drugs in older people and involve general practitioners in community education. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1999;24(4):289–297. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.1999.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scottish Government Primary care investment. 2015. https://news.gov.scot/news/primary-care-investment (accessed 4 Aug 2018)

- 18.NHS England More than 400 pharmacists to be recruited to GP surgeries by next year. 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2015/11/pharmacists-recruited/ (accessed 4 Aug 2018) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.University of Glasgow GPs at the Deep End. 2016. https://www.gla.ac.uk/researchinstitutes/healthwellbeing/research/generalpractice/deepend/about/ (accessed 4 Aug 2018)

- 20.Information Services Division Scotland . Quality & Outcomes Framework (QOF) for April 2015–March 2016 prevalence reported from QOF registers (practices with any contract type) Health and Social Care Partnership level data; 2016. http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/General-Practice/Quality-And-Outcomes-Framework/2015-16/Register-and-prevalence-data.asp (accessed 4 Aug 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 21.NHS Scotland Therapeutics Branch National therapeutic indicators 2014/15. http://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/publications/DC20141201nti.pdf (accessed 4 Aug 2018)

- 22.NHS Education for Scotland Pharmacists working in GP practices. 2016. http://www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/education-and-training/by-discipline/pharmacy/pharmacists/prescribing-and-clinical-skills/pharmacists-working-in-gp-practices.aspx (accessed 4 Aug 2018)

- 23.Jorgenson D, Laubscher T, Lyons B, Palmer R. Integrating pharmacists into primary care teams: barriers and facilitators. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22(4):292–299. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scottish Government . The 2018 General Medical Services contract in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart F, Caldwell G, Cassells K, et al. Building capacity in primary care: the implementation of a novel ‘Pharmacy First’ scheme for the management of UTI, impetigo and COPD exacerbation. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018 Jan 24;:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1463423617000925.. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurant M, van der Biezen M, Wijers N, et al. Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7:CD001271. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anonymous Why drug shortages occur. Drug Ther Bull. 2015;53(3):33–36. doi: 10.1136/dtb.2015.3.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gloor C, Dantés M, Graefenhain E, et al. An evaluation of medicines shortages in Europe with a more in-depth review of these in France, Greece, Poland, Spain, and the United Kingdom. 2013 http://static.correofarmaceutico.com/docs/2013/10/21/evaluation.pdf (accessed 5 Sep 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hitchings AW, Baker EH, Khong TK. Making medicines evergreen. BMJ. 2012;345:e7941. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scottish Government Model of Care Polypharmacy Working Group . Polypharmacy guidance. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Scottish Government; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calderwood C. The Chief Medical Officer for Scotland’s annual report 2015/16: realising realistic medicine. Edinburgh: Scottish Government; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329(7456):15–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]