Abstract

Anxiety sensitivity (AS), or the fear of anxious arousal, is a transdiagnostic risk factor predictive of a wide variety of affective disorders. Whereas AS is widely studied via self-report, the neurophysiological correlates of AS are poorly understood. One specific issue this may help resolve are well-established gender differences in mean-levels of AS. The current study evaluated late positive potential (LPP) for images designed to target AS during an emotional picture viewing paradigm. Structural equation modeling was used to examine convergent and discriminant validity for self-report AS and the LPP for AS images, considering gender as a potential moderator. Analyses were conducted in an at-risk sample of 251 community adults (M age = 35.47, SD = 15.95; 56.2% female; 53.6% meeting for a primary Axis I anxiety or related disorder). Findings indicated that the AS image LPP was significantly, uniquely associated with self-report AS, controlling for the LPP for unpleasant images, in females only. Mean levels of AS self-report as well as the AS image LPP were higher in females than in males. These findings provide initial support for the AS image LPP as a useful neurophysiological correlate of AS self-report in females. These findings also provide support for a biological cause for gender differences in AS.

Keywords: anxiety sensitivity, emotional picture viewing paradigm, late positive potential, gender

Anxiety Sensitivity (AS) reflects the tendency to interpret anxiety-related sensations as indicative of impending physical, psychological, or social consequences. Early work investigating AS demonstrated contributions to the etiology and maintenance of panic disorder (PD; Schmidt, Lerew, & Jackson, 1997). Recently, AS has also been implicated in the development of several other affective disorders (Schmidt, Zvolensky, & Maner, 2006), including depression (Allan, Capron, Raines, & Schmidt, 2014), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; Allan, Macatee, Norr, & Schmidt, 2014), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; Raines, Oglesby, Capron, & Schmidt, 2014), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; (Lang, Kennedy, & Stein, 2002). Further, AS can be treated through brief interventions, and reductions in AS through these interventions have resulted in subsequent reductions in psychopathological symptomatology (Schmidt, Capron, Raines, & Allan, 2014; Schmidt et al., 2007; Smits et al., 2008). However, our understanding of the biological processes underlying this risk factor is limited, particularly in at-risk samples.

To gain a more complete understanding of constructs like AS, research is increasingly focused on establishing connections between neurophysiological processes and the phenotypic presentation of these constructs (Cuthbert & Insel, 2013; Insel, Cuthbert, Garvey, Heinssen, Pine, Quinn, Sanislow, & Wang, 2010; Luck et al., 2011). For example, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has been used to identify neural processes associated with self-reported AS (Ball et al., 2012; Killgore et al., 2011; Poletti et al., 2015; Stein, Simmons, Feinstein, & Paulus, 2007). The preponderance of fMRI studies support positive associations between self-reported AS and activity in the insula and ACC during emotional processing tasks (Killgore et al., 2011; Poletti et al., 2015; Stein et al., 2007). These findings are consistent with conceptual models of AS focused on misinterpretation of physiological arousal as the insula is involved in interoception (i.e., detection of the body’s internal state; Craig, 2003, 2009) and the ACC is in turn involved in monitoring interoceptive signals from the insula to generate error signals when differences between predicted and observed bodily states are detected (Paulus & Stein, 2006).

Although fMRI is useful in identifying broad neural processes and in locating the anatomical sites of these processes (Luck et al., 2011), there are several limitations of this approach to identifying neurophysiological correlates of AS. First, fMRI has poor temporal resolution, limiting its capacity to capture the rapid processing of threat believed to be central to the AS construct. Second, fMRI is costly, reducing the feasibility of collecting large samples that can be easily replicated. The cost of fMRI also limits its applicability from a treatment perspective as neurophysiological correlates of AS identified through this approach would likely be too expensive to be used clinically (Luck et al., 2011). An approach utilizing event-related potentials (ERPs) may be better suited to identify neurophysiological correlates of self-reported AS. ERPs have excellent temporal resolution. In addition, data collection using ERPs is relatively inexpensive. Therefore, large samples can be gathered, studies can be easily replicated, and neurophysiological indicators could be used in treatment settings (Luck et al., 2011).

Several studies have used ERP approaches to study AS, primarily in the context of behavioral inhibition using response inhibition paradigms (Beste et al., 2013; Beste, Domschke, Radenz, Falkenstein, & Konrad, 2011; Sehlmeyer et al., 2010). In these studies, AS was significantly related to the Nogo P3 ERP, reflecting a positive deflection approximately 300 ms after a correctly executed Nogo trial in which participants were required to inhibit a prepotent response. In addition, AS has been associated with error-related negativity (ERN), a negative going ERP approximately 200 ms after an incorrect Nogo trial that reflects an individual’s evaluation of their failure to inhibit a response (Beste et al., 2013) as well as an attenuated P300 in response to threat (an expected or unexpected shock; Nelson, Hodges, Hajack, & Shankman, 2015). These particular ERPs, however, have several shortcomings as neurophysiological correlates of AS. There is limited face validity for a direct association between the Nogo P3 and the ERN and elevated AS, suggesting that these effects are indirect, through some third construct. There are also questions of specificity as several other broad psychological constructs have been associated with these ERPs in similar contexts, including impulsivity, executive control, depression, anxiety, and substance use (e.g., Bokura, Yamaguchi, & Kobayashi, 2001; Olvet & Hajcak, 2008; Ruchsow et al., 2008). In sum, face validity and specificity issues cast doubt on whether these ERPs represent unique neurophysiological correlates of AS.

One promising but underexplored ERP representation of AS is the modulation of the late positive potential (LPP), elicited during an emotional picture viewing paradigm. The LPP is a sustained positive amplitude beginning around 300–500ms and reaching maximal amplitude at approximately 1000ms (Cuthbert, Schupp, Bradley, Birbaumer, & Lang, 2000). The emotional picture viewing paradigm is a relatively straightforward task in which people are asked to view a series of images, typically varying in valence (i.e., positive and negative; Bradley, 2009; Cuthbert et al., 2000; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1997). The LPP during an emotional picture viewing paradigm appears to be driven primarily by appetitive or aversive motivational salience of a stimulus as reflected by greater centro-parietal amplitude for pleasant and unpleasant images compared to neutral images (e.g., Cuthbert et al., 2000; Keil et al., 2002; Schupp et al., 2004).

Whereas the LPP is also associated with other broad psychological constructs including executive control, depression, anxiety, and substance use (Dunning et al., 2011; Hajcak, McNamara, Foti, Ferri, & Keil, 2013; McNamara & Hajcak, 2010; McNamara & Proudfit, 2014; Namkoong et al., 2004), there is emerging evidence that underlying individual differences can modulate LPP responsivity to images when images are selected to elicit these individual differences. For example, Gable and Poole (2014) explored the relations between LPP reactivity to images meant to evoke anger and self-reported BIS/BAS ratings. They found significant positive relations between a self-reported dimension of BAS, drive, and LPP amplitudes in response to anger images. Recent literature regarding specific phobia has found differences in LPP response to phobia-relevant images in those with and without a diagnosed specific phobia (e.g., Leutgeb, Schafer, & Schienle, 2009; Michalowski et al., 2009; Miltner et al., 2005). In addition, people with substance abuse issues have potentiated LPP responses to images associated with these substances (e.g., Dunning et al., 2011; Franklin, Stam, Hendriks, & van den Brink, 2003). These findings demonstrate that individual differences, such as elevated fear of spiders, BAS levels, or substance use patterns are positively associated with LPP amplitudes when images designed to target particular individual differences are used. Therefore, it is likely that the LPP in response to images designed to elicit AS in an emotional picture viewing paradigm would provide a face valid approach to evaluate individual differences in AS.

A potentially important consideration when examining the association between AS self-report and the LPP in response to AS images is the well-documented gender differences in self-reported AS. Higher mean-level AS has consistently been found in females, compared to males, in both community and clinical samples (Allan, Oglesby, Uhl, & Schmidt, 2016; Deacon et al., 2003; Schmidt & Koselka, 2000). It is unclear whether these gender differences correspond to objective differences in anxious arousal or whether females are more sensitive to their arousal (McLean & Anderson, 2009). Regarding physiological arousal, a proximal neighbor to neurophysiological measurement, some studies report enhanced arousal to anxiety-provoking stimuli for females, others for males, and still others report no differences (e.g., Kelly, Forsyth, & Karekla, 2006; Kelly, Tyrka, Anderson, Price, & Carpenter, 2008; Maltzman, 1979; Stoney, Davis, & Matthews, 1987). Although no studies have examined AS differences using ERPs, several studies have examined gender differences in ERP response to unpleasant images. Syrjänen and Wiens (2013) recently found no differences between males and females in LPP amplitude toward negatively-valenced images. They did find that females rated the negative images as more unpleasant than did males. Whereas Gardener, Carr, McGregor, and Felmingham (2013) found gender differences, these differences only emerged when people were asked to increase the emotional salience of the image, and not in the condition when people were asked to view the image only. Together, these findings tentatively suggest that whereas self-reported AS differs in males and females, it is likely that the LPP in response to AS images is not different across males and females.

The purpose of the current study was to establish LPP response to images selected and reviewed by a panel of experts to evoke AS-relevant threat responses as a unique neurophysiological correlate of self-reported AS in an at-risk community sample. To that end, the LPP was examined using the passive viewing condition from an emotional picture viewing and regulation paradigm in which people were asked to passively view images. To demonstrate specificity between self-reported AS and the LPP in response to AS images, both the LPP in response to AS images and the LPP in response to unpleasant images were examined as correlates of AS self-report. Further, given that the LPP in response to images is typically greatest in the centro-parietal region as well as the large sample size in this study, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to model the relations between the LPPs and self-reported AS as latent variables. As Clayson and Miller (2017) recently highlighted, SEM explicitly accounts for measurement error. Unlike pooling together multiple sensors (which pools together measurement error as well as true score), SEM allows for the modeling of multiple sensors within the centro-parietal region to create a latent LPP variable, which will, in turn, reduce measurement error. Finally, given gender differences in self-reported AS, multi-group analysis, within an SEM framework, was conducted to explore gender differences across measurement and structural parameters of the LPP in response to AS and unpleasant images and self-reported AS. Consistent with prior studies (e.g., Allan et al., 2016), it was expected that self-report AS would be higher in females than in males. These differences were not expected to extend to LPP response to either image type (e.g., Syrjänen and Wiens, 2013). However, it was tentatively hypothesized that these differences would result in attenuated relations between self-reported AS and the LPP in response to AS images in males compared to females.

Method

Participants

The sample comprised 280 people presenting for participation in a clinical trial targeting risk factors for anxiety and mood disorders. Inclusionary criteria included scoring at or above the community mean on at least one of several risk factors for anxiety and mood disorders (i.e., AS, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness) and English speaking to ensure comprehension. Exclusionary criteria included evidence of uncontrolled bipolar or psychotic spectrum disorders, serious suicidal intent that would warrant immediate hospitalization, unstable medication usage (i.e., not on a stable dose for at least three months prior to study entry), and/or participation in current psychotherapy. Only people ages 18 years and older were eligible for participation.

Of the 280 eligible people enrolled, a total of 29 were removed for technical failures (n = 9), falling asleep during the task (n = 10), or an inability to complete either the task or self-report measures (n = 10). This resulted in 251 people for analysis (M age = 35.47 years, SD = 15.95; 56.2% female). The majority of the sample identified as White (60.2%), with 25.9% identifying as Black, 2.4% Asian, .4% Pacific Islander, .4% American Indian, and 11.6% other (e.g. bi-racial). Of the 251 people used for analysis, 78 (29.1%) identified as a veteran. A breakdown of primary diagnoses for the sample is provided in Table 1. Of note, 53.6% of the sample were diagnosed with a primary anxiety or related disorder (i.e., obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder). All people were screened for neurological conditions and visual impairments.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Frequencies and Percentages of Sample

| Diagnosis | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Adjustment Disorder | 1 | 0.4% |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 2 | 0.8% |

| Anorexia | 1 | 0.80% |

| Anxiety (NOS) | 11 | 4.4% |

| Anxiety Due to a Medical Condition | 1 | 0.80% |

| Axis II Disorder Probable | 3 | 1.2% |

| Binge Eating Disorder | 1 | 0.80% |

| Bipolar I Disorder | 7 | 2.8% |

| Body Dysmorphic Disorder | 1 | 0.80% |

| Cannabis Use Disorder | 1 | 0.4% |

| Cocaine Use Disorder | 4 | 1.6% |

| Depression (NOS) | 3 | 1.2% |

| Eating Disorder NOS | 1 | 0.4% |

| Excoriation Disorder | 4 | 3.30% |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 31 | 12.4% |

| Hallucinogen Use Disorder | 1 | 0.4% |

| Hoarding | 2 | 0.8% |

| Illness Anxiety Disorder | 2 | 0.8% |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 26 | 10.4% |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 3 | 1.2% |

| Opioid Use Disorder | 1 | 0.4% |

| Other Specified Trauma | 2 | 0.8% |

| Panic Disorder without Agoraphobia | 9 | 3.6% |

| Persistent Depressive Disorder | 29 | 11.6% |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 37 | 14.7% |

| Pyschotic Symptoms | 1 | 0.80% |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 43 | 17.1% |

| Social Anxiety Disorder (Performance only) | 1 | 0.4% |

| Somatic Symptom Disorder | 2 | 0.8% |

| Specific Phobia | 3 | 1.2% |

| Trichotillomania | 2 | 0.8% |

| Unable to assess | 1 | 0.4% |

Note. N = 251. NOS = Not Otherwise Specified.

Self-Report Measures

Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3)

The ASI-3 (Taylor et al., 2007) is an 18-item self-report measure designed to assess an individual’s tendency to interpret anxiety-related sensations as potentially harmful or dangerous. The ASI-3 was adapted from the original Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI; Reiss, Peterson, Gursky, & McNally, 1986) to improve the psychometrics of the three proposed subdimensions of AS: cognitive concerns, physical concerns, and social concerns. Respondents use a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (very little) to 4 (very much) to indicate the extent to which each item reflects their typical experience. Previous research has demonstrated the ASI-3 to have strong psychometrics (Taylor et al., 2007). In the current study, the ASI-3 and its subdimensions demonstrated good to excellent internal reliability (αs = .84–.93).

Clinician Administered Measure

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-V, Research Version (SCID-5-RV)

All psychiatric diagnoses were determined using the SCID-5-RV (First, Williams, Karg, & Spitzer, 2015). The SCID-5-RV was administered by highly trained doctoral level therapists with extensive training in SCID-5-RV administration and scoring, including reviewing training tapes, observing live administrations, and conducting practice interviews with other trained therapists. In addition, all SCID-5-RV results were reviewed by a licensed clinical psychologist to ensure accurate diagnoses. Previous studies conducted in our lab using an identical structured clinical interview training and scoring paradigm have demonstrated high interrater agreement (e.g., over 80% with a kappa of .86; Schmidt, Norr, Allan, Raines, & Capron, 2016).

Experimental Procedure

This study was approved by the Florida State University Institutional Review Board. People first completed a baseline session during which they completed the structured clinical interview and a packet of self-report questionnaires. Following this, they were scheduled for their neurophysiological assessment session. Neurophysiological testing was conducted in a dimly lit, sound-attenuated room. Stimuli were presented using a Dell OptiPlex 780 computer running E-Prime version 2.0.8.90. Stimuli were presented full screen on a 21″ CRT color monitor at a viewing distance of 100 cm, subtending a visual angle of 25.5° × 16.1°. The recording session consisted of several different tasks, including an emotional picture paradigm. All tasks were administered in a standard order. The emotional picture viewing paradigm was administered second, following a resting state task. Total recording time lasted between 2.5 and 3 hours. The current study analyzed data collected from the emotional picture viewing paradigm.

Experimental Stimuli

Emotional Picture Viewing Paradigm

In the emotional picture paradigm, people observed 204 images total (60 neutral images and 144 emotional images that were split into 6 content categories: unpleasant, pleasant, suicide, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and AS). Unpleasant, pleasant, and neutral images were selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention, 1999), where pleasant images contained erotica, unpleasant images depicted threatening scenes and images of mutilated bodies, and neutral images included buildings, household objects, and neutrally rated pictures of humans. IAPS images were selected based on normative affective ratings.1 For the pleasant images only, separate picture sets were selected for males and females to maximize levels of arousal and valence for each gender.

Images within the other content categories (suicide, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, AS) were selected by a panel of experts (i.e., graduate students and Ph.Ds) in the field of clinical psychology. Regarding AS, images were selected from internet image searches and evaluated by the panel of experts for their relevance to the AS construct. All images included people experiencing anxiety-related symptoms feared by those with high AS, and were selected to elicit emotional processing specifically associated with each of the three AS subscales: Cognitive concerns, physical concerns, and social concerns. Images selected to elicit AS cognitive concerns portrayed people who appeared to have “racing thoughts” and/or cognitive dyscontrol (e.g., a woman with her hands on her head and eyes closed who appears to be yelling). Images selected to elicit AS physical concerns portrayed people experiencing physiological symptoms of anxiety (e.g., a man clutching his chest as if he were having a heart attack). Images used to elicit AS social concerns included images of individuals with noticeable signs of anxiety (e.g., a woman blushing and appearing anxious while several fingers are pointed at her in close range). In total, 24 pictures were selected to represent AS.2

Images were presented on screen for 6 sec each, preceded by the regulation instruction “Increase,” “Decrease,” or “View” presented on an otherwise blank black screen for 2 seconds, similar to paradigms used to elicit emotional responding in previous literature (Moser, Hajcak, Bukay, & Simons, 2006). All image types, other than neutral images contained trials with increase, decrease, and view instructions. For “Increase” and “Decrease” instructions, people were instructed prior to the experimental recording to increase or decrease the intensity of their initial emotional reaction to the image based on the given regulation instruction; if instructed to view image, people were told to allow their initial emotional response to happen naturally with no manipulation of response. For all images, people were asked to focus on the full image for the entire time it was presented on screen. A fixation point was presented centrally as a blue dot during a 2 second inter-trial interval. People completed a practice task in which two images were presented within each regulation category to familiarize them with the instructions.

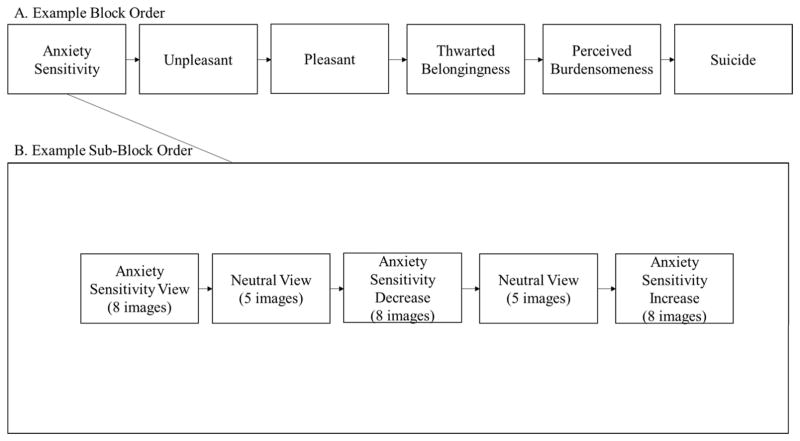

Emotional images were divided into six blocks (AS, unpleasant, pleasant, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicide) which were further subdivided into five sub-blocks (see Figure 1). All 24 trials for a specific emotional content type were presented within a single block, which was split up into 3 blocks of 8 trials for each specific instruction and content type (e.g., all 8 AS View trials were presented in a single block, all 8 Negative View trials were presented in a single block, etc.). Each of these blocks was then separated by a block of Neutral View trials (5 images). Thus, a block of AS trials would be composed of the following sub-blocks: AS View - Neutral View - AS Increase - Neutral View - AS Decrease. The order of the presentation of the instruction blocks (i.e., which instruction type was presented first, second, and third) was counterbalanced across participants. Individual images were also counterbalanced across instruction type, such that images were randomly chosen from a set of 24 images so that each instruction type was composed of 8 distinct images. Blocks and sub-blocks were counterbalanced across people. Regulation instruction and affective ratings were distributed across valence category and proportionately across content category within each stimulus order. An exception to this was that the neutral images were only presented with the regulation instruction “View” to avoid confusion of trying to regulate emotional responses to a non-affective image. In the current study, only the view trials for the AS, neutral, unpleasant, and pleasant images were used.

Figure 1.

Example of presentation of Emotional Picture Viewing Paradigm image presentation.

Stimulus Delivery and Physiological Response Measurement

ERP data were collected using a Dell OptiPlex 780 computer and Neuroscan Acquire software. Two 64-channel Neuroscan SynAmps RT amplifiers and a BrainVision actiCap 96-channel cap were used to measure EEG responses (1000 Hz sampling rate, with an online analog bandpass filter of 0.05 – 100 Hz). The midline electrode AFz was used as the ground and FCz was used as an online reference electrode. Offline, the data were re-referenced to the averaged mastoids (electrodes TP9 and TP10). Horizontal electrooculogram activity was recorded from electrodes placed lateral to the outer canthus of each eye, while vertical electrooculogram activity was recorded from electrodes placed above and below the left eye. Electrodes were filled using high-chloride (10%) Abrasive Electrolyte-Gel (EasyCap). All impedance values were below 10 kohms throughout the recording session.

Data Processing

Data were first downsampled to 250 Hz, then the Fully Automated Statistical Thresholding for EEG artifact Rejection algorithm (FASTER; Nolan, Whelan, & Reilly, 2010), an EEGLAB plugin, was used to apply high-pass (0.1 Hz; transition band = 0.05 Hz) and low-pass (40 Hz; transition band = 2.50 Hz) FIR filters for artifact detection and rejection. The FASTER algorithm provides researchers with enhanced data processing efficiency and standardization of artifact rejection parameters compared to traditional visual inspection methods (Hatz et al., 2015; Nolan, Whelan, & Reilly, 2010). Moreover, the FASTER algorithm has demonstrated equal or superior reliability when compared to traditional visual inspection methods of artifact rejection (Hatz et al., 2015; Nolan et al., 2010). FASTER uses a z-score threshold of ± 3 to detect artifacts (i.e. muscular artifacts, eye blinks and saccades, electrode “pop-offs”, etc.) within single channels, individual epochs, independent components, and within-epoch channels (for more information regarding specifics of the FASTER procedure see Nolan et al., 2010). For data processing, epochs were computed using the full trial length and a 200 ms pre-stimulus baseline (i.e., −200 ms to 6000 ms epochs). Following artifact detection and rejection, deviant channels were interpolated using the EEGLAB spherical spline interpolation function in line with standard guidelines (Keil et al., 2013; Picton et al., 2000). Deviant channels were identified as those with z-scores outside of the ± 3 threshold for the following, pre-defined, parameters: 1) variance, 2) median gradient value, 3) amplitude range, and 4) deviation of amplitude mean. Participants had an average of 3.45 channels interpolated (SD = 1.46). Relevant to the channels used in the current study, five participants total had their data interpolated for these channels (one for CPz, three for Pz, and one for CP1).

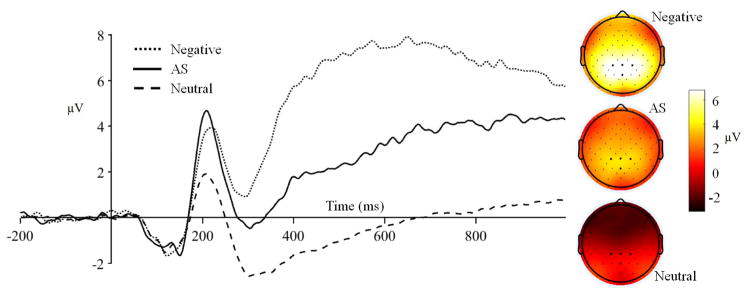

Electrophysiological Data Extraction

Consistent with the time course of the LPP in our grand-averaged data (see Figure 2) and with prior studies (Gable & Harmon-Jones, 2013; Schönfelder, Kanske, Heissler, & Wessa, 2013), the LPP was measured as the mean voltage from 500–1000 ms after stimulus onset. Based on the scalp topography of the LPP in our data and the selection of centro-parietal electrodes in previous studies, the LPP was measured at CPz, CP1, CP2, and Pz (Brown, van Steenbergen, Band, de Rover, & Nieuwenhuis, 2012; Gable, Adams, & Proudfit, 2015; Thiruchselvam, Blechert, Sheppes, Rydstrom, & Gross, 2011; see Figure 2). Whereas a prior psychometric study found that the LPP had adequate internal consistency (split-half reliability) with eight trials (Moran, Jendrusina, & Moser, 2013), split-half reliability, calculated from the average mean amplitude across CPz, Pz, CP1, and CP2 for participants with at least 8 trials was low for the AS Images LPP (α = .40) and for the Unpleasant Images LPP (α = .55).

Figure 2.

Late Positive Potential Waveforms. Grand-averaged waves pooled from CPz, Pz, CP1, and CP2 (bold electrodes). Topographical maps depict mean amplitude 500–1000 ms after image onset relative to baseline.

Data Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics and preliminary analyses were first calculated. Because reliability estimates for the AS and Unpleasant Images LPPs were low, exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) were conducted in Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1996–2017), within each set of images to determine whether all images clustered together. To assess whether the AS and Unpleasant Image LPP trials were unidimensional, parallel analysis was conducted and the scree plot was examined. Parallel analysis involves generating random data sets based on the same number of items and people in the real data matrix. The plot of the eigenvalues from the real data can then be compared to the 95th percentile of the eigenvalues from the simulated data. The number of eigenvalues from the real data above the value at the 95th percentile from the simulated data is considered to be the likely number of factors present (Reise, Waller, & Comrey, 2000). Examination of the scree plot involves searching for the “elbow” of the plot, or the point at which eigenvalues form a descending linear trend (Cattell, 1966). The scree plot supports the number of factors at this elbow.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was then conducted to examine the relations between the AS and Unpleasant Images LPPs and AS Self-Report as well as to examine potential gender differences in these relations. Full information maximum likelihood with the Yuan-Bentler scaled chi-square (Y-B χ2) was used to analyze the data. The Y-B χ2 was used to assess model fit, with a nonsignificant value indicating that exact model fit cannot be dismissed. In addition, the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with 90% confidence intervals (CIs), and the squared root mean residual (SRMR) were used as indices of approximate fit. CFI values greater than .90 suggest adequate fit, values greater than .95 suggest good fit. RMSEA and SRMR values less than .05 suggest good fit. Finally, lower bound CIs less than .05 suggest that good fit cannot be ruled out and upper bound CIs greater than .10 suggest that poor fit cannot be ruled out (Bentler, 1990; Browne & Cudeck, 1992; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was first used to examine measurement invariance within each factor separately. Measurement invariance was examined sequentially following the procedures recommended by Meredith (1993). Metric invariance was first examined to determine whether the factor loadings were identical across males and females. Next, scalar invariance was examined to determine whether the indicator intercepts were equivalent. Finally, full invariance was examined to determine whether the indicator residuals were equivalent. Models were compared using the Y-B adjusted χ2 test, with a nonsignificant value indicating that invariance held. If invariance was not achieved, the model was examined for partial invariance (Steenkamp & Baumgartner, 1998). If at least partial invariance was achieved across metric and scalar invariance, the factors were considered generally equivalent and the factor variances and factor means were then compared. Once all CFA models were examined and, if measurement invariance was established, an SEM was examined, including the AS and Unpleasant Images LPP factors predicting the AS Self-Report factor. Structural pathways were compared across males and females for equivalence using the Y-B adjusted χ2 test.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables are provided in Table 2. Skew and kurtosis were within acceptable limits. Therefore, no corrections to the data were conducted. Trial counts for males and females were compared for AS and Unpleasant images. There was no significant difference between males (M = 7.65, SD = .63) and females (M = 7.68, SD = .65) in the number of available AS image trials, F(1, 249) = .11, p = .75. There was also no significant difference between males (M = 7.72, SD = .54) and females (M = 7.63, SD = .68) in the number of available Unpleasant image trials, F(1, 249) = 1.20, p = .28. A total of 80 males (72.73%) and 107 females (75.89%) had data available for all 8 AS images. A total of 84 males (76.36%) and 99 females (70.21%) had data available for all 8 Unpleasant images.

Table 2.

Correlations for Anxiety Sensitivity and Unpleasant Images Late Positive Potentials and Anxiety Sensitivity Self-Report by Gender

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AS CPz | -- | .88* | .93* | .94* | .38* | .38* | .38* | .37* | −.01 | −.06 | .02 |

| 2. AS Pz | .92* | -- | .85* | .86* | .36* | .42* | .36* | .35* | −.02 | −.06 | .04 |

| 3. AS CP1 | .96* | .88* | -- | .90* | .36* | .37* | .36* | .34* | −.01 | −.03 | .01 |

| 4. AS CP2 | .97* | .90* | .94* | -- | .38* | .40* | .39* | .38* | −.07 | −.10 | −.01 |

| 5. Unpleasant CPz | .38* | .38* | .37* | .38 | -- | .91* | .97* | .97* | .06 | .05 | .25* |

| 6. Unpleasant Pz | .31* | .40* | .31* | .31* | .91* | -- | .90* | .92* | .01 | −.01 | .21* |

| 7. Unpleasant CP1 | .38* | .39* | .38* | .38* | .98* | .92* | -- | .95* | .06 | .04 | .22* |

| 8. Unpleasant CP2 | .34* | .36* | .34* | .36* | .98* | .91* | .96* | -- | −.001 | .02 | .19* |

| 9. AS Physical | .08 | .13 | .10 | .08 | .03 | .08 | .05 | .04 | -- | .62* | .60* |

| 10. AS Cognitive | .15 | .19* | .19* | .14 | .07 | .13 | .09 | .10 | .59* | -- | .68* |

| 11. AS Social | .22* | .23* | .23* | .17* | .11 | .21* | .13 | .10 | .48 | .56* | -- |

|

| |||||||||||

| Male Mean | 3.16 | 2.87 | 3.17 | 3.24 | 6.10 | 5.92 | 6.05 | 5.82 | 9.40 | 8.58 | 11.45 |

| SD | 3.76 | 3.45 | 3.83 | 3.56 | 4.32 | 3.90 | 4.25 | 3.91 | 6.54 | 6.75 | 6.07 |

| Female Mean | 4.33 | 4.37 | 4.34 | 4.25 | 8.12 | 7.76 | 7.76 | 8.05 | 9.30 | 10.55 | 13.57 |

| SD | 4.93 | 4.53 | 4.70 | 4.49 | 5.22 | 5.07 | 4.94 | 4.95 | 5.89 | 7.44 | 5.91 |

Note. Correlations for females are on the lower diagonal and correlations for males are on the upper diagonal. AS = Anxiety Sensitivity. LPP = Late Positive Potential. SD = Standard Deviation.

p < .05.

Preliminary basic experimental effects were examined to explore differences in mean amplitude (for pooled CPz, Pz, CP1, and CP2 sensors) between Neutral, AS, and Unpleasant images using repeated measures ANOVA. There was a significant effect of condition, F(2, 498) = 319.46, p < .001, ηP2 = .56. Probing this condition using t tests revealed significant differences in mean amplitude between Neutral (M amplitude = .11, SD = 2.54) and AS images (M amplitude = 3.79, SD = 4.15; t(249) = 15.09, p < .001), between Neutral and Unpleasant images (M amplitude = 7.07, SD = 4.64; t(249) = 25.41, p < .001), and between AS and Unpleasant images (t(249) = 10.75, p < .001).

Exploratory Factor Analyses of AS and Unpleasant Images Late Positive Potentials

EFAs within each set of items were conducted to determine whether all items clustered together within the AS Images LPP trials and within the Unpleasant Images LPP trials. Exploratory bifactor models were utilized to allow for nuisance variance when fitting CFA solutions. Parallel analysis and examination of the scree plot both supported a one-factor solution for the AS Images LPP. Model fit statistics were excellent as well (χ2 = 8.42, df = 13, p > .05, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, 90% CI [.00, .04]). Parallel analysis and examination of the scree plot also supported a one-factor solution for the Unpleasant Images LPP. Again, model fit statistics supported this model (χ2 = 17.49, df = 13, p > .05, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .04, 90% CI [.00, .08]).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Invariance Testing of Anxiety Sensitivity and Unpleasant Images Late Positive Potentials

All CFA models and fit statistics and indices are provided in Table 3. The AS and Unpleasant Images LPP factors were each fit in separate models. For the AS Images LPP, the model testing metric invariance did not significantly degrade model fit compared to the model with just configural invariance (χ2 = 1.39, df = 3, p > .05). The model testing scalar invariance did not degrade model fit compared to the model with metric invariance only (χ2 = 5.88, df = 3, p > .05). Fixing the residual variances across LPP waves indicated that full invariance was met (χ2 = 1.46, df = 4, p > .05). Factor variance equality was not achieved (χ2 = 9.23, df = 1, p < .01), indicating that the AS Images LPP factor demonstrated increased variance in females compared to factor variance in males. Finally, there was a significant AS Images LPP factor mean difference (χ2 = 4.90, df = 1, p < .05). The factor mean for males was set to 0 to anchor the factor score whereas the female factor mean was significantly greater at 1.14.

Table 3.

Model Fit Statistics and Indices for Confirmatory Factor Analyses of Anxiety Sensitivity and Unpleasant Images Late Positive Potentials and Anxiety Sensitivity Self-Report

| CFA Models | Y-B χ2 | df | Δ Y-B χ2 | CFI | RMSEA | 90% CI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||||

| AS Images LPP | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Configural Invariance | 1.17 | 4 | -- | 1.00 | .00 | .00 | .06 | .00 |

| Metric Invariance | 2.51 | 7 | 1.39 | 1.00 | .00 | .00 | .04 | .01 |

| Scalar Invariance | 7.69 | 10 | 5.88 | 1.00 | .00 | .00 | .08 | .02 |

| Full Invariance | 7.15 | 14 | 1.46 | 1.00 | .00 | .00 | .03 | .02 |

|

| ||||||||

| Unpleasant Images LPP | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Configural Invariance | 10.93* | 4 | -- | .99 | .12 | .04 | .20 | .00 |

| Metric Invariance | 18.38* | 7 | 3.64 | 1.00 | .08 | .00 | .21 | .02 |

| Scalar Invariance | 31.15*** | 10 | 13.73** | .98 | .13 | .08 | .18 | .02 |

| Partial Scalar Invariance | 21.16 | 9 | 2.33 | .99 | .10 | .05 | .16 | .02 |

| Partial Full Invariance | 24.89 | 13 | 5.98 | .99 | .09 | .03 | .14 | .04 |

|

| ||||||||

| AS Self-Report | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Metric Invariance | 2.55 | 2 | 2.58 | 1.00 | .05 | .00 | .19 | .03 |

| Scalar Invariance | 11.40* | 4 | 8.43* | .96 | .12 | .04 | .21 | .06 |

| Partial Scalar Invariance | 3.40 | 3 | .87 | 1.00 | .03 | .00 | .16 | .04 |

| Full (Partial Scalar) Invariance | 9.08 | 6 | 7.07 | .98 | .06 | .00 | .14 | .07 |

Note. AS = Anxiety Sensitivity. LPP = Late Positive Potential. Metric invariance = equal factor loadings. Scalar invariance = equal intercepts. Y-B = Yuan-Bentler. CFI = comparative fit index. RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. CI = confidence interval. SRMR = square root mean square residual. LL = lower limit. UL = upper limit.

For the Unpleasant Images LPP, the model testing metric invariance did not significantly degrade model fit (χ2 = 3.64, df = 3, p > .05). The model testing scalar invariance significantly degraded model fit (χ2 = 13.73, df = 3, p < .01). Freeing the intercept for the CP2 wave resulted in partial scalar invariance (χ2 = 2.33, df = 2, p > .05). Partial full invariance was met fixing the residual variances for all LPP waves (χ2 = 5.98, df = 4, p > .05). Factor variance equality was achieved (χ2 = 2.35, df = 1, p > .05). Finally, there was a significant Unpleasant Images LPP factor mean difference (χ2 = 10.77, df = 1, p < .001). The factor mean for males was set to 0 to anchor the factor score whereas the female factor mean was significantly greater, at 1.98.

Together, these findings demonstrate that the AS Images LPP as well as the Unpleasant Images LPP represent the same construct in males and females. Whereas the same construct is being assessed in males and females, there were several differences between males and females. First, the LPP in response to both types of images was elevated in females compared to males. Second, for the AS Images LPP, there was a greater spread of scores for females than for males.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Invariance Testing of Anxiety Sensitivity Self-Report

Measurement invariance was also examined for AS Self-Report factor. The model testing metric invariance did not significantly degrade model fit (χ2 = 2.55, df = 2, p > .05). The model testing scalar invariance significantly degraded model fit (χ2 = 8.43, df = 2, p < .05). Freeing the intercept for the AS physical concerns scale resulted in partial scalar invariance (χ2 = .87, df =1, p > .05). Fixing the residual variances across scales indicated that full (partial scalar) invariance was met (χ2 = 7.07, df = 3, p > .05). Factor variance equality was achieved (χ2 = .13, df = 1, p > .05). Finally, there was a significant AS Self-Report factor mean difference (χ2 = 6.65, df = 1, p < .01). The factor mean for males was set to 0 to anchor the factor score whereas the female factor mean was significantly greater, at 1.76. Therefore, this construct was measured similarly in males and females and females had higher self-reported levels of AS.

Structural Model Examining the Relations between Late Positive Potentials and Anxiety Sensitivity Self-Report

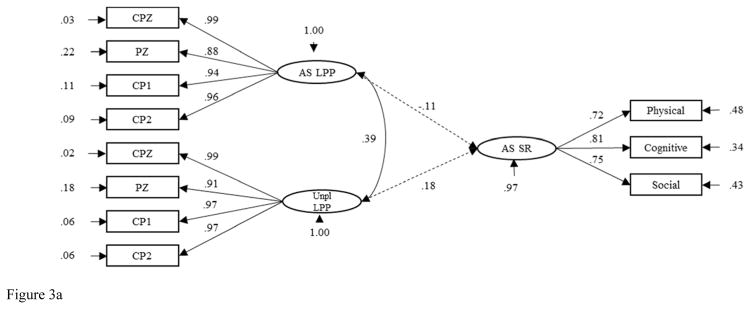

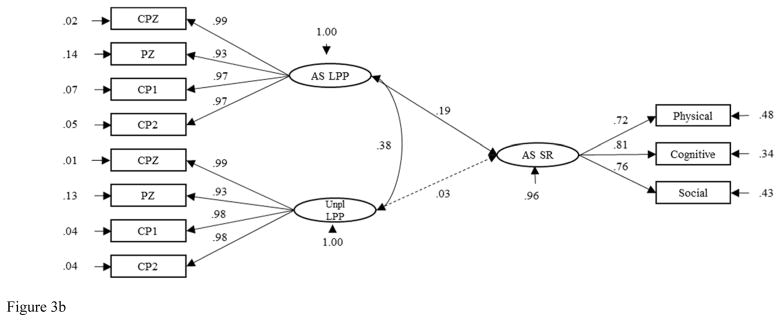

SEM was conducted to examine the relations between the AS and Unpleasant Images LPP factors and the AS Self-Report factor across males and females. This model fit the data adequately (Y-B χ2 = 177.69, CFI = .98 RMSEA = .07, 90% CI [.05, .09], SRMR = .05). Model results are reported for males and females separately (see Figures 3a and 3b). The relation between the Unpleasant Images LPP factor and the AS Self-Report factor was nonsignificant for males and females both. In contrast, the relation between the AS Images LPP factor and the AS Self-Report factor was significant and positive for females (β = .19, p < .05) and nonsignificant and negative for males (β = −.11, p > .05).3

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. Structural Equation Model of the Relations between Anxiety Sensitivity Self-Report and AS and Unpleasant Images LPPs in Males. AS = Anxiety Sensitivity. LPP = Late Positive Potential. Unpl = Unpleasant. SR = Self-Report.

Figure 3b. Structural Equation Model of the Relations between Anxiety Sensitivity Self-Report and AS and Unpleasant Images LPPs in Females. AS = Anxiety Sensitivity. LPP = Late Positive Potential. Unpl = Unpleasant. SR = Self-Report.

Given that not all participants had data available for 8 trials, which demonstrated adequate reliability in Moran et al. (2013), this final SEM was re-examined, including only those participants who had data available for 8 AS images and 8 Unpleasant images (62 males, 80 females). The relation between the Unpleasant Images LPP factor and the AS Self-Report factor was again nonsignificant for males (β = .10, p > .05) and for females (β = .06, p > .05). Further, the relation between the AS Images LPP factor and the AS Self-Report factor was significant for females β = .27, p < .05) but not for males (β = .02, p > .05).

In the SEM models, the only significant relation was between the AS Images LPP factor and the AS Self-Report factor in females. These findings were consistent regardless of whether participants with data for all 8 AS and unpleasant images were included. Therefore, the gender-moderated relation between the AS Images LPP factor and the AS Self-Report factor appears to be robust to the limitation that not all participants had data available for all 8 images.

Discussion

In the current study, the LPP elicited from AS images was uniquely related to AS self-report, controlling for the LPP elicited by unpleasant images, in females only. Females reported higher levels of AS than did men, in both self-report and AS image LPPs. The finding of gender differences in self-reported levels of AS is consistent with prior studies (Allan et al., 2016; Deacon et al., 2003). The finding of a lack of gender differences for the LPP in response to negatively-valenced images is inconsistent with several prior studies (Rozenkrants & Polich, 2008; Syrjänen & Wiens, 2013).

This study found mean-level differences for AS self-report as well as for the AS image LPP, coupled with a correlation between AS self-report and AS image LPP in females. This may help clarify conflicting findings regarding gender differences often found in the literature (e.g., Stewart, Taylor, & Baker, 1997). Two contrasting hypotheses regarding gender differences in AS self-report can be posited. One hypothesis is that these self-reported differences reflect biological differences in AS (the substance model). The competing hypothesis is that differences in AS self-report instead reflect biased reporting of AS (the artifact model; Egloff & Schmukle, 2004; Feingold, 1994), typically posited to occur due to sociocultural influences (see McLean & Anderson, 2009). The differences in AS across self-report and in response to images supports the substance model and suggests these differences may be biological in nature. Support for this can be found in a study by Egloff and Schmukle (2004). They examined gender differences in explicit (i.e., self-report) and implicit anxiety measures (i.e., the Implicit Association Test-Anxiety and the Emotional Stroop task). They found that females reported more anxiety on the explicit and implicit anxiety measures. They also found that the correlations between the explicit and implicit measures was only significant for females (rs = .14–.30), and was consistent with the correlation coefficient found between the AS image LPP and AS self-report in the current study (r = .19). Together, the finding of differences in anxiety-related constructs across multiple domains supports gender differences in experienced anxiety as reflecting biological differences.

Regardless of the gender differences, these findings demonstrate that the AS image LPP can serve as a neurophysiological correlate of self-reported AS, especially for women. Broadly, the LPP is modulated by the motivational significance of a stimulus. Our findings extend beyond the well-documented effect of emotion on the LPP (e.g., Keil et al., 2002) by showing that the LPP can index individual differences relevant to specific stimulus categories. This is consistent with recent research showing that the LPP can be affected by stimulus interpretation, context, and focus on specific features of a stimulus (Dennis & Hajcak, 2009; Dunning & Hajcak, 2009; Hajcak, Dunning, & Foti, 2009; Judah et al., 2015). For example, compared to non-spider phobics, spider phobics show enhanced LPP for images of spiders (Michalowski et al., 2009; Miltner et al., 2005). Similarly, people high in BAS drive show enhanced LPP for images designed to evoke anger than do people low in BAS drive (Gable & Poole, 2014). These findings support the emerging usefulness of the LPP as a marker of stimulus salience related to individual difference variables.

A second implication of the results is that AS may involve increased processing of visual cues that depict anxiety-related physiological responses, at least in females. This may be taken as evidence that such stimuli have heightened motivational salience, likely due to perceived threat, for females with high levels of AS (see Schupp et al., 2004). This finding may be important for future studies examining reappraisal, cognitive bias training, and exposure-based interventions to target AS within the context of treating anxiety disorders.

Given that this was the first study to demonstrate the relation between AS self-report and AS-image LPP, and this effect was moderated by gender, more work is needed to substantiate this relation. For example, examination of relations among multiple measurement domains (i.e., neurophysiological, behavioral tasks, self-report) might help clarify the nature of AS. In addition, whereas the pictures selected to elicit AS were selected by a panel of experts in AS, it is unclear whether all pictures elicited an enhanced LPP. Examination of images at an individual level might aid in refining the process of using the AS-image LPP as a reliable neurophysiological correlate of self-reported AS. Another future direction might be to select images balanced across the lower-order dimensions of AS as self-report measures of these lower-order AS dimensions have demonstrated specificity with particular affective disorders (e.g., Allan, Capron, et al., 2014; Olatunji & Wolitzky-Taylor, 2009).

The development of AS images that target lower-order AS dimensions might be particularly useful for the development of an index of AS that spans both self-report and neurophysiological variables. This type of index has been termed a psychoneurometric index by Patrick and colleagues (Patrick et al., 2013; Patrick, Durbin, & Moser, 2012). The development of a psychoneurometric index—consistent with the RDoC approach (e.g., Insel et al., 2010)—is based on the construct network approach of Cronbach and Meehl (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955; Meehl, 1959). Patrick et al. (2013) suggest an iterative process in which latent variables, purported to capture the essence of an underlying construct, are composed of several equally contributing manifest variables across measurement domains. For example, a latent AS construct would be best captured as comprising not only self-report indicators of AS but also neurophysiological indicators. The development of such an index would leverage a strength of SEM against a weakness of neurophysiological approaches. Namely, whereas the use of single indicators extracted in a laboratory setting, as is common in ERP studies, can result in findings (either positive or negative) partially driven by measurement error, a psychoneurometric index would capture variance shared across several ERPs, limiting the possibility of such spurious findings (Lilienfeld, 2014; Patrick et al., 2013). The current study demonstrates one of several possible ways to assess ERPs within an SEM framework.

The finding that the AS image LPP is related to AS self-report in females has implications for clinical practice and future examination of anxiety pathology. Future studies might utilize this LPP to accurately assess AS in females. Much as cut-scores for at-risk status have been developed for self-report measures of AS using factor mixture modeling approaches (i.e., Allan, Korte, Capron, Raines, & Schmidt, 2014; Allan, Raines, et al., 2014), similar approaches could be used to identify clinically relevant cut-scores for the AS image LPP. Whereas several brief interventions have been successfully developed for reducing self-reported AS (Schmidt et al., 2014; Smits et al., 2008), it is unclear whether these same treatments are associated with reductions in reactivity to stimuli related to elevated AS and whether these reductions can be identified at the neurophysiological level. Therefore, future studies are needed to examine malleability of the AS image LPP, especially in females.

These implications should be considered in the context of the sample in this study. The current study was conducted in a sample of people with elevated levels of both AS and psychopathology. For example, mean-level ASI-3 scores were at 31.67 (SD = 16.51), which is well above the factor mixture model-derived cut-score (i.e., 23) identifying people with high levels of likely maladaptive AS (Allan, Korte et al., 2014; Allan, Raines, et al., 2014). Further, more than 94% of the sample met diagnostic criteria for at least one DSM-5 disorder. Therefore, whereas these findings are relevant from a perspective of understanding AS as a maintenance factor for psychopathology, it is unclear whether these same findings would emerge in a sample with lower levels of AS and/or psychopathology. Replication of these findings in a less at-risk sample would allow researchers to understand the AS Image LPP in relation to AS self-report in the context of psychopathology prevention.

There were several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings of the current study. First, this is the first study to use these images to elicit AS. Whereas the specific association between self-reported AS and these images suggests that the images elicit AS, several potential moderators of this relation were not considered, including arousal level. Future studies are needed to validate these particular AS images. Although efforts have been made to do this in an independent sample, these validation efforts should be conducted in studies collecting valence and arousal information as well as LPP in response to these images. In addition, reliability estimates for the AS Image LPPs and the Unpleasant Image LPPs were low. These estimates were below the adequate reliability reported in Moran et al. (2013). These findings might reflect differences in sample composition. The current sample comprised people with high levels of psychopathology. Although sample composition is not provided in Moran et al. (2013), it would seem unlikely that they tested reliability in a sample with such elevated levels of psychopathology. Therefore, more trials might be necessary to obtain acceptable levels of reliability in populations with elevated psychopathology. Finally, whereas only the view images from the emotional picture paradigm were used in the current study, people were also asked to suppress or enhance their response to images within this task. Therefore, it is possible that these manipulations might have influenced response to images during the view condition. However, people were asked to suppress or enhance across all images (with the exception of neutral images). Therefore, these associations appear to be robust to the impact of these other task demands. Further, several recent studies examining the effects of suppressing and enhancing responses to images counterbalanced suppress and enhance blocks of trials and found no significant effect of order, suggesting a limited impact of prior trial demands on later trials (Krompinger, Moser, and Simons, 2008; Moser et al., 2006; Moser, Krompinger, Dietz, & Simons, 2009).

In spite of these limitations, this was the first study to demonstrate convergent validity between self-reported AS and AS-image LPP. This finding can be used as a building block to develop multi-unit of analysis indices, such as a psychoneurometric index, that might more fully capture constructs such as AS. Further, once these psychoneurometric indices are developed, they can be used in intervention and prevention efforts to more fully understand how our treatments impact AS and related psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by a National Institutes of Mental Health Award (F31-MH105067-01) awarded to the first author. This investigation was also supported in part by the Military Suicide Research Consortium (MSRC), an effort supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs (Award No. W81XWH-10-2-0181).

Footnotes

The unpleasant IAPS images were as follows: 1050, 1120, 1525, 3000, 3010, 3030, 3053, 3060, 3068, 3069, 3080, 3102, 3120, 3130, 3266, 6200, 6210, 6230, 6243, 6250, 6260, 6300, 6510, and 6830. As indicated in the IAPS technical appendices, average arousal ratings for these images was 5.61 (SD = 2.19) and average valence ratings for these images was 3.43 (SD = 1.74).

Additional validity information for these images has been collected in a sample of 419 people (M age = 39.90, SD = 12.89; 67.06% female) completing an online survey on Amazon’s Mturk, including ratings of arousal in the AS images used in the current study. Using the same 1–9 SAM-calculated rating scale as used in validating the IAPS images, mean arousal ratings for these images was 5.05 (SD = 1.66) and the mean valence rating was 4.39 (SD = .66). Reliability was excellent (α = .96) for AS image arousal ratings. In this sample, correlations between the arousal ratings of the AS images and AS self-report (assessed via ASI-3) were nonsignificant in males (r = .05) and significant in females (r = .17, p < .01). There were no significant differences in SAM-calculated valence (p = .87) or arousal (p = .40) ratings in this sample.

These results were replicated using analysis of covariance to examine the impact of gender, AS image LPP, Unpleasant Image LPP, and gender by the image type interactions on AS self-report. The overall model was marginally significant, F(5, 249) = 2.22, p = .053. Further, the interaction between gender and the AS image LPP was marginally significant, F(1, 249) = 3.14, p = .08. Probing this interaction using ordinary least squares regression revealed a marginally significant relation between the AS image LPP and AS self-report in females (β = .18, p = .051) and a nonsignificant relation in males (β = −.09, p = .41).

References

- Allan NP, Capron DW, Raines AM, Schmidt NB. Unique relations among anxiety sensitivity factors and anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28(2):266–75. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan NP, Korte KJ, Capron DW, Raines AM, Schmidt NB. Factor Mixture Modeling of Anxiety Sensitivity: A Three-Class Structure. Psychological Assessment. 2014;26(4):1184–1195. doi: 10.1037/a0037436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan NP, Macatee RJ, Norr AM, Schmidt NB. Direct and Interactive Effects of Distress Tolerance and Anxiety Sensitivity on Generalized Anxiety and Depression. 2014:530–540. doi: 10.1007/s10608-014-9623-y. [DOI]

- Allan NP, Oglesby ME, Uhl A, Schmidt NB. Cognitive risk factors explain the relations between negative affect and social anxiety for males and females. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2016:1–15. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2016.1238503. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Allan NP, Raines AM, Capron DW, Norr AM, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Identification of anxiety sensitivity classes and clinical cut-scores in a sample of adult smokers: Results from a factor mixture model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28(7):696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball TM, Sullivan S, Flagan T, Hitchcock CA, Simmons A, Paulus MP, Stein MB. Selective effects of social anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, and negative affectivity on the neural bases of emotional face processing. NeuroImage. 2012;59(2):1879–1887. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck aT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer Ra. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beste C, Domschke K, Radenz B, Falkenstein M, Konrad C. The functional 5-HT1A receptor polymorphism affects response inhibition processes in a context-dependent manner. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(9):2664–2672. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beste C, Konrad C, Uhlmann C, Arolt V, Zwanzger P, Domschke K. Neuropeptide S receptor (NPSR1) gene variation modulates response inhibition and error monitoring. NeuroImage. 2013;71:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokura H, Yamaguchi S, Kobayashi S. Electrophysiological correlates for response inhibition in a Go/NoGo task. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112(12):2224–2232. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00691-5. http://doi.org/S1388-2457(01)00691-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden JW, Peterson DR, Jackson EA. The Beck Anxiety Inventory in nonclinical samples: Initial psychometric properties. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1991;13:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM. Natural selective attention: Orienting and emotion. Psychophysiology. 2009;46(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SBRE, van Steenbergen H, Band GPH, de Rover M, Nieuwenhuis S. Functional significance of the emotion-related late positive potential. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012;6 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell RB. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1966;1:245–276. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2003;13(4):500–505. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. How do you feel--now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews: Neuroscience. 2009;10:59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach L, Meehl P. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin. 1955;129(1):3–9. doi: 10.1037/h0040957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. 2013. pp. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, Schupp HT, Bradley MM, Birbaumer N, Lang PJ. Brain potentials in affective picture processing: covariation with autonomic arousal and affective report. 2000;52:95–111. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(99)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon BJ, Abramowitz JS, Woods CM, Tolin DF. The Anxiety Sensitivity Index-Revised: Psychometric properties and factor structure in two nonclinical samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:1427–1449. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis TA, Hajcak G. The late positive potential: A neurophysiological marker for emotion regulation in children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2009;50(11):1373–1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02168.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning JP, Hajcak G. See no evil: Directing visual attention within unpleasant images modulates the electrocortical response. Psychophysiology. 2009;46(1):28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning JP, Parvak MA, Hajcak G, Maloney T, Alia-Klein N, Woicik PA, … Goldstein RZ. Motivated attention to cocaine and emotional cues in abstinent and current cocaine users-an ERP study. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;33:1716–1723. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer R. Structured clinical interview for DSM-5, research version. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Foot M, Koszycki D. Gender differenes in anxiety-related traits in patients with panic disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;20:123–130. doi: 10.1002/da.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin IHA, Stam CJ, Hendriks VM, van den Brink W. Neurophysiological evidence for abnormal cognitive processing of drug cues in heroin dependence. Psychopharmacology. 2003;170:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable PA, Adams DL, Proudfit GH. Transient tasks and enduring emotions: The impacts of affective content, task relevance, and picture duration on the sustained late positive potential. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2015;15:45–54. doi: 10.3758/s13415-014-0313-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable PA, Harmon-Jones E. Does arousal per se account for the influence of appetitive stimuli on attentional scope and the late positive potential? Psychophysiology. 2013;50(4):344–350. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable PA, Poole BD. Influence of trait behavioral inhibition and behavioral approach motivation systems on the LPP and frontal asymmetry to anger pictures. 2014:182–190. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gardener EK, Carr AR, MacGregor A, Felmington KL. Sex differences and emotion regulation: An event-related potential study. PloS one. 2013;8:e73475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Dunning JP, Foti D. Motivated and controlled attention to emotion: Time-course of the late positive potential. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2009;120(3):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Moser JS, Holroyd CB, Simons RF. The feedback-related negativity reflects the binary evaluation of good versus bad outcomes. Biological Psychology. 2006;71(2):148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatz F, Hardmeier M, Bousleiman H, Rüegg S, Schindler C, Fuhr P. Reliability of fully automated versus visually controlled pre- and post-processing of resting-state EEG. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2015;126:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel Thomas R, Cuthbert Bruce, Garvey Marjorie, Heinssen R, Pine Daniel S, Quinn Kevin, Sanislow Charles, Wang P. Research Domain Criteria ( RDoC ): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judah MR, Grant DM, Frosio KE, White EJ, Taylor DL, Mills AC. Electrocortical Evidence of Enhanced Performance Monitoring in Social Anxiety. Behavior Therapy. 2015;47(2):274–285. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil A, Bradley MM, Hauk O, Rockstroh B, Elbert T, Lang PJ. Large-scale neural correlates of affective picture processing. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(5):641–649. doi: 10.1017.S0048577202394162. http://doi.org/10.1017.S0048577202394162, S0048577202394162 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil A, Debener S, Gratton G, Junghöfer M, Kappenman ES, Luck SJ, … Yee CM. Committee report: Publication guidelines and recommendations for studies using electroencephalography and magnetoencephalography. Psychophysiology. 2013;51:1–21. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MM, Forsyth JP, Karelka M. Sex differences in response to a panicogenic biological challenge procedure: An experimental evaluation of panic vulnerability in a non-clinical sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1421–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MM, Tyrka AR, Anderson GM, Price LH, Carpenter LL. Sex differences in emotional and physiological responses to the Trier Social Stress Test. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2008;39:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WDS, Britton JC, Price LM, Gold AL, Deckersbach T, Rauch SL. Neural correlates of anxiety sensitivity during masked presentation of affective faces. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28(3):243–249. doi: 10.1002/da.20788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krompinger JW, Moser JS, Simons RF. Modulations of electrophysiological response to pleasant stimuli by cognitive reappraisal. Emotion. 2008;8:132–137. doi: 10.1037/528-3542.8.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Kennedy CM, Stein MB. Anxiety sensitivity and PTSD among female victims of intimate partner violence. Depression and Anxiety. 2002;16(2):77–83. doi: 10.1002/da.10062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang P, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. Motivated attention: Affect, activation, and action. Attention and Orienting: Sensory and Motivational Processes 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb V, Schafer A, Schienle A. An event-related potential study on exposure therapy for patients suffering from spider phobia. 2009;82:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: a review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136(4):576–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO. Behaviour Research and Therapy The Research Domain Criteria ( RDoC ): An analysis of methodological and conceptual challenges. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;62:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, Mathalon DH, O’Donnell BF, Hmlinen MS, Spencer KM, Javitt DC, Uhlhaas PJ. A roadmap for the development and validation of event-related potential biomarkers in schizophrenia research. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;70(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltzman I. Habituation of the GSR and digital vasomotor components of the orienting reflex as a consequence of task instructions and sex differences. Physiological Psychology. 1979;7:213–220. [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Anderson ER. Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehl PE. Some ruminations on the validation of clinical procedures. Canadian Journal of Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie. 1959;13(2):102–128. doi: 10.1037/h0083769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michalowski JM, Melzig CA, Weike AI, Stockburger J, Schupp HT, Hamm AO. Brain Dynamics in Spider-Phobic Individuals Exposed to Phobia-Relevant and Other Emotional Stimuli. 2009;9(3):306–315. doi: 10.1037/a0015550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltner WHR, Trippe RH, Krieschel S, Gutberlet I, Hecht H, Weiss T. Event-related brain potentials and affective responses to threat in spider/snake-phobic and non-phobic subjects. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2005;57(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran TP, Jendrusina AA, Moser JS. The psychometric properties of the late positive potential during emotion processing and regulation. Brain Research. 2013;1516:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser JS, Hajcak G, Bukay E, Simons RF. Intentional modulation of emotional responding to unpleasant pictures: An ERP study. 2006;43:292–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser JS, Krompinger JW, Dietz J, Simon RF. Electrophysiological correlates of decreasing and increasing emotional responses to unpleasant pictures. Psychophysiology. 2009;46:17–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan H, Whelan R, Reilly RB. FASTER: Fully Automated Statistical Thresholding for EEG Artifact Rejection. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2010;192:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Wolitzky-Taylor KB. Anxiety sensitivity and the anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review and synthesis. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(6):974–99. doi: 10.1037/a0017428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvet DM, Hajcak G. The error-related negativity (ERN) and psychopathology: Toward an endophenotype. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(8):1343–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Durbin CE, Moser JS. Reconceptualizing antisocial deviance in neurobehavioral terms. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(03):1047–1071. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Venables NC, Yancey JR, Hicks BM, Nelson LD, Kramer MD. A Construct-Network Approach to Bridging Diagnostic and Physiological Domains: Application to Assessment of Externalizing Psychopathology. 2013;122(3):902–916. doi: 10.1037/a0032807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, Stein MB. An Insular View of Anxiety. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton TW, Betin S, Berg P, Donchin E, Hillyard SA, Johnson R, … Taylor MJ. Guidelines for using human event-related potentials to study cognition: Recording standards and publication criteria. Psychophysiology. 2000;37:127–15. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.3720127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletti S, Radaelli D, Cucchi M, Ricci L, Vai B, Smeraldi E, Benedetti F. Neural correlates of anxiety sensitivity in panic disorder: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Research - Neuroimaging. 2015;233(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raines AM, Oglesby ME, Capron DW, Schmidt NB. Obsessive compulsive disorder and anxiety sensitivity: Identification of specific relations among symptom dimensions. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2014;3(2):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Waller NG, Comrey AL. Factor analysis and scale revision. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:287–297. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozenkrants B, Polich J. Affective ERP processing in a visual oddball task: Arousal, valence, and gender. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008;119:2260–2265. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.07.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchsow M, Groen G, Kiefer M, Hermle L, Spitzer M, Falkenstein M. Impulsiveness and ERP components in a Go/Nogo task. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2008;115(6):909–915. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Capron DW, Raines AM, Allan NP. Randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a brief intervention targeting anxiety sensitivity cognitive concerns. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0036651. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schmidt NB, Eggleston AM, Woolaway-Bickel K, Fitzpatrick KK, Vasey MW, Richey JA. Anxiety Sensitivity Amelioration Training (ASAT): A longitudinal primary prevention program targeting cognitive vulnerability. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21(3):302–319. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Koselka M. Gender differences in patients with panic disorder: Evaluating cognitive mediation of phobic avoidance. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:533–550. doi: 10.1023/A:1005562011960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Lerew DR, Jackson RJ. The role of anxiety sensitivity in the pathogenesis of panic: prospective evaluation of spontaneous panic attacks during acute stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(3):355–64. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.3.355. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9241937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Lerew DR, Jackson RJ. Prospective evaluation of anxiety sensitivity in the pathogenesis of panic: replication and extension. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108(3):532–537. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Norr AM, Allan NP, Raines AM, Capron DW. Randomized clinical trial targeting anxiety sensitivity for patients with suicidal ideation. 2016 doi: 10.1037/ccp0000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ, Maner JK. Anxiety sensitivity: prospective prediction of panic attacks and Axis I pathology. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40(8):691–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönfelder S, Kanske P, Heissler J, Wessa M. Time course of emotion-related responding during distraction and reappraisal. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2013;9(9):1310–1319. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp HT, Cuthbert B, Bradley M, Hillman C, Hamm A, Lang P. Brain processes in emotional perception: Motivated attention. Cognition & Emotion. 2004;18(5):593–611. doi: 10.1080/02699930341000239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sehlmeyer C, Konrad C, Zwitserlood P, Arolt V, Falkenstein M, Beste C. ERP indices for response inhibition are related to anxiety-related personality traits. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(9):2488–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semlitsch HV, Anderer P, Schuster P, Presslich O. A solution for reliable and valid reduction of ocular artifacts, applied to the P300 ERP. Psychophysiology. 1986;23:695–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and Validation of a Self-Report Measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29(2):83–102. doi: 10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JAJ, Berry AC, Rosenfield D, Powers MB, Behar E, Otto MW. Reducing anxiety sensitivity with exercise. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25(8):689–699. doi: 10.1002/da.20411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Simmons AN, Feinstein JS, Paulus MP. Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety-prone subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):318–327. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Taylor S, Baker JM. Gender differences in dimensions of anxiety sensitivity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1997;11:179–200. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(97)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoney CM, Davis MC, Matthews KA. Sex differences in physiological responses to stress and in coronary heart disease: A causal link? Psychophysiology. 1987;24:127–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1987.tb00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrjänen E, Wiens S. Gender moderates valence effects on the late positive potential to emotional distractors. Neuroscience Letters. 2013;551:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, Deacon B, Heimberg RG, Ledley DR, … Cardenas SJ. Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(2):176–88. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiruchselvam R, Blechert J, Sheppes G, Rydstrom A, Gross JJ. The temporal dynamics of emotion regulation: An EEG study of distraction and reappraisal. Biological Psychology. 2011;87:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]