SYNOPSIS

Outcomes after critical illness remain poorly understood. Conceptual models, developed by other disciplines can serve as a framework by which to increase knowledge about outcomes after critical illness. This chapter reviews three models to 1) understand the distinct and interrelated content of outcome domains, 2) to review the components of functional status, and 3) to describe how injuries and illnesses relate to disabilities and impairments afterwards.

Keywords: Critical Illness, Survivorship, Disability, Functional Status

Introduction

Critical care medicine, in its modern form, has been in existence for over a half-century. Since its inception, several shifts in the focus of care have occurred.1 In the 1960s and 1970’s, when the first modern ICUs were established, the goals of care were to resuscitate shock and to support via mechanical ventilation. Once our specialty became familiar with these therapies, we began to look for ways to improve outcomes for patients with critical illness. This ushered in the era of the 1990s and 2000s where numerous clinical trials focused on reducing mortality were conducted and modern, evidenced-based critical care became possible. Mortality from critical illness began to decline as the result of these trials and our growing experience in caring for the critically ill.

These long sought-after reductions in mortality, however, revealed a new problem facing critical care medicine—a growing number of patients who survive their illness. Some of those who survive critical illness with recover with no or only minor sequelae of their illness. Others will suffer with newly acquired (or worsened) alterations to physical, cognitive, and mental health function that alters their lives in fundamental ways, including in the ability to live independently. Thus, the focus of the modern era of critical care medicine has expanded to not only save lives while patients are in the ICU, but toward a goal of understanding and improving the long-term outcomes after critical illness.

Yet many factors contribute to our limited knowledge about outcomes after critical illness. First, relatively few studies have been published as illustrated by a comparison of the number of papers published in critical care medicine in contrast with those studies focused on outcomes among survivors of critical illness (Figure 1).2 While the number of published studies in both critical care in general and in critical illness survivorship has increased since the beginning of our field, those with a focus on critical care outpace those focused on survivorship nearly 40 to 1. Second, these studies are heterogeneous. For example, a scoping review of cognitive, physical, and mental health outcomes in survivors of critical illness found that in the 425 manuscripts published on the topic over the past 40 years, 250 different tools were used to assess outcomes.2 Third, the outcome domains considered important differ between researchers and survivors/their families.3 As a first step toward standardizing outcomes a consensus panel comprised of clinicians, researchers, patients, and funding agencies used a Delphi process to address these gaps through the development of a core outcomes set for survivors of mechanical ventilation.4 Nevertheless, additional work to understand better outcomes after critical illness remains.

Figure 1. Critical care publications from 1970 until 2013.

Panel A demonstrates the overall number of publications in critical care (solid line) and the number of randomized trials in critical care (dashed line). Panel B demonstrates the number of publications focused on outcomes among survivors of critical illness. As with panel A, the solid line represents the overall number of publications and the dashed line represent the number of randomized trials. While both panels demonstrate that the number of publications and randomized trials have increased over time, the scale of the Y-axes should be noted. The number of overall publications is approximately 40 times larger than number of publications focused on outcomes for survivors of critical illness.

From Turnbull AE, Rabiee A, Davis WE, et al. Outcome Measurement in ICU Survivorship Research From 1970 to 2013: A Scoping Review of 425 Publications. Crit Care Med. 2016 Jul;44(7):1267–77. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001651.

A second means by which to inform outcomes used in clinical trials is to increase the understanding conceptually how clinical variables are related to outcomes such as functional status and health-related quality of life. While study of outcomes other than mortality is new to the field of critical care, research on these outcomes has been the focus of other fields for many decades. This research led to the development of several useful models that can be applied to survivors of critical illness to advance the field and enhance our knowledge base of the outcomes after critical illness.5–7 Therefore, this chapter will review three of these models to understand 1) the distinct and interrelated content of outcome domains, 2) the components of functional status and their relationships, and 3) how injuries and illnesses relate to disabilities and impairments afterwards. These models can serve as a framework by which future clinical trials and observational studies can be designed.

Outcome Domains after Critical Illness

As reflected by the number of outcome tools used in studies of survivors of critical illness, outcomes can be considered across domains from cells to populations. Thus, to advance the field of critical care outcomes research, a better understanding of specific outcome domains, their content, and their interrelatedness is important.

To this end, the model proposed by proposed Wilson and Cleary is helpful.7 This model proposes a framework that classifies patient outcomes into five domains starting with those outcomes that describe the mechanisms of disease and progress to those that measure behaviors and feelings. Hence, each domain integrates information from the prior domains to arrive at increasing levels of complexity (Figure 2A). Further adding to the complexity outcome domains are considerations of the effects of individual and environmental characteristics. Let us now consider the content of each of these domains and their application to critical illness.

Figure 2. Continuum of Outcome Domains for Survivors of Critical Illness.

Outcomes for survivors of critical illness can be divided into five interrelated domains. Panel A demonstrates each of these domains, providing a conceptual definition for each. Panel B applies these domains and concepts to survivors of critical illness. Each domain considers a specific aspect of patient outcomes. As outcomes move from left to right in the figure, however, information from the previous domains are integrated into subsequent ones, increasing the complexity of each outcome domain. At higher levels, individual and environmental characteristics also play a role.

Relationships between non-adjacent domains are possible.

Data from Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995;273:59–65

The first domain is biological and physiological variables. Outcomes in this domain describe the function of cells, organs and organ systems. These outcomes are familiar to ICU clinicians because they comprise measures that are focused on the pathophysiologic basis of disease, physiological outcomes, and clinical outcomes (e.g., physical exam findings, laboratory data, and other biomarkers of organ function). This domain also includes diseases, illnesses, and injuries (e.g., sepsis, congestive heart failure, trauma) (Figure 2B).

The second domain is symptoms. This domain is focused on patients’ subjective perceptions of abnormalities in physical, emotional, and cognitive states that are integrated from a number of sources. Although less commonly reported in studies of critical illness survivors, these outcomes are also familiar to clinicians and researchers (e.g., pain, fatigue, anxiety) (Figure 2B).8,9 Symptoms can be related to biological and physiological variables (e.g., pain and a broken leg), but not always (e.g., dyspnea and left ventricular ejection fraction). Thus, interventions that target biological and physiological variables may not affect symptoms.

The third domain is functional status. Functional status defines an individual’s ability to perform a defined physical, cognitive, or social task or set of tasks (e.g., self-care activities, test of cardiorespiratory fitness, test of cognition). Functional status integrates biological and physiological variables and symptoms along with factors related to person (e.g., intrinsic motivation) and environment (e.g., modifications to one’s home environment for a wheelchair, using lists to remember things). Functional status, though commonly used to refer only to physical function or disability, at its broadest sense, is also focused on cognitive and psychological function (Figure 2B). Because of the increasing interest in functional status outcomes by both clinicians and researchers among survivors of critical illness we will explore functional status in greater detail in the next section including how biological and physiological variables and symptoms can alter function.

The fourth domain is health perception. Health perception is the subjective integration of biological and physiological variables, symptoms, functional status, and mental health. In other words, it is how a patient considers his or her health in light of other factors. Though health perception uses information from prior domains (e.g., symptoms and functional status), its subjective nature means that health perceptions can vary widely from patient to patient (e.g., some may care very little about major health problems and some may care a lot about minor health problems). For example, a survivor of critical illness may have a positive opinion of her health status considering how sick she once was (Figure 2B).

The fifth and final domain is health-related quality of life (HRQOL). HRQOL describes one’s satisfaction and happiness as related to one’s health. Because HRQOL is a common outcome of concern to clinicians and is a common outcome measure in critical care studies, several key points are worthy of mention. First, it is important to distinguish HRQOL from overall quality of life. Overall quality of life can be influenced by a number of factors aside from one’s health such as employment, family relationships, and spirituality.10 For example, a survivor of critical illness may recover to her baseline functional status without additional chronic medical problems, but report overall poor quality of life because she is socially isolated (e.g., a widow whose children live far away). Second, the relationship between HRQOL and objective life circumstances is often not as strong as perceived by clinicians and researchers. In other words, those with significant impairments in function or disabilities can have high levels of HRQOL related to the fact that people may change their expectations and goals as life circumstances change (e.g., adjust to the ‘new normal’).11 Thus, a survivor of critical illness with significant impairments or disabilities may have what she considers to be a good quality of life in spite of outward appearances to the contrary (Figure 2B). Finally, becuase HRQOL represents a patient’s perspective on life based on the integration of objective and subjective data (with each of these interacting at multiple levels), interventions which target different domains (e.g., biological or physiological variables, symptoms, or functional status) may not alter HRQOL. This key point has important implications for researchers when considering outcomes for clinical trials and may explain, in part, the negative findings of trials focused on the recovery of survivors of critical illness.12,13

Functional Status

Outcome studies and clinical trials in critical care are increasingly focused on some aspect of functional status (i.e., physical function, cognitive function, psychological function).14–32 Despite this interest, the major concepts related to functional status and nuances of this domain are not well understood. Therefore, this section will review the components of functional status and describe their relationship.

Functional status is an overarching term which refers to the activities (i.e., physical, cognitive, social, and spiritual) one performs in the normal course of life to meet basic needs, fulfill usual roles, and maintain their health or well-being.5 Thus, although functional status is frequently used to refer only to one’s physical function, at its broadest level it also incorporates cognitive, mental health, social, and spiritual aspects of one’s life.

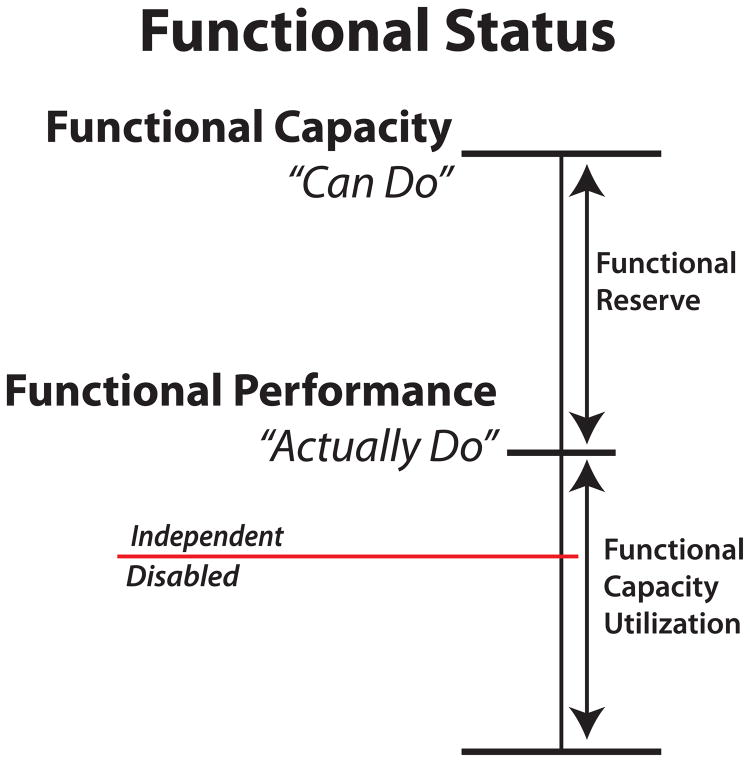

There are four components to functional status: functional capacity, functional performance, functional reserve, and functional capacity utilization (Figure 3). Functional capacity is one’s maximum potential to perform an activity. Functional performance is the activities needed to meet one’s basic needs and maintain one’s health and well-being. Functional reserve is the difference between functional capacity and functional performance. The inverse of functional reserve is functional capacity utilization. Functional capacity utilization is proportion of one’s functional capacity he or she uses to achieve functional performance. Let us consider each of these components in turn.

Figure 3. Conceptual Framework of Functional Status.

Functional status is an overarching term for what activities people do in the normal course of their lives to meet basic needs. It is comprised of four components: functional capacity, functional performance, functional reserve, and functional capacity utilization. Functional capacity is one’s maximum potential to perform an activity and represents what one “can do” (top horizontal line). Functional performance represents what one “actually does” in day-to-day life (middle horizontal line). The difference between functional capacity and functional performance is functional reserve. Functional capacity utilization is the amount of one’s functional capacity that is used to achieve functional performance. Because functional performance represents the activities that one does, it represents the ability to live independently. If one’s functional performance falls below a certain threshold (red horizontal line) one moves from being able to live independently to being disabled.

Adapted from Leidy NK. Functional status and the forward progress of merry-go-rounds: Toward a coherent analytical framework. Nurs Res. 1994:43:196–202; with permission.

Functional capacity is the maximal performance in a standardized environment. In other words, it is what one “can do” under conditions of maximal exertion. Measures of functional capacity can be though of as performance on standardized tests of function. For example, dynamometry to measure muscle strength or the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) to measure cognitive function. Tests such as the 6-minute walk also assess functional capacity but determine the integration of multiple body systems (i.e., cardiac, respiratory and musculoskeletal).

Functional performance on the other hand describes the activities that people do on a daily basis, in their usual environment rather than a standardized one. In other words, functional performance is what one “actually does”. Functional performance can be assessed, for example, by assessing how far and how often one travels away from his or her home33 or by assessing the acitivies needed to live independently such as bathing, dressing, preparing meals, or managing medications.34–37 Because functional performance measures are what one actually does, a performance at a level below that required for independent living is considered disability.6

Functional reserve and functional capcaity utilization describe the relationship between one’s functional capacity and one’s functional performance. Functional reserves represent the “stores” of abilities that can be used to accomplish a task. Thus, a person who uses little of their functional capacity to perform daily activities therefore has a low functional capacity utilization and has high levels functional reserve that can be called upon to perform strenuous activities. In contrast, a person functioning close to near maximal abilities to perform their basic daily activities has a high functional capacity utilization and little functional reserve that can be called upon to perform more strenuous activities. Moreover, functioning close to one’s maximum ability (e.g., a high functional capacity utilization) requires high levels of exertion. As anyone who has performed a task requiring high levels of exertion (e.g., sprinting “all-out” or being timed when solving a complex crossword puzzle) can relate to, it is difficult to maintian a high level of exertion for long periods of time. Thus, if a person’s functional capacity utilization is high (and high levels of exertion are required to perform one’s basic daily activities) one may alter the frequency with basic activities are performed or even stop performing them all together, either by necessity or by choice.

To understand better these concepts that describe functional status, let us compare the functional status of two individuals. First, we will consider a recreational athlete who runs and weight trains 5 times per week (Figure 4A). She has no chronic illnesses and is in her mid 30s. Because she exercises regularly, she has a high level of cardiopulmonary fitness and strength. She is free of the effects of chronic disease and age on her overall function. She has a high functional capactiy. Her routine daily activies (functional performance), therefore, require minimal exertion (low functional capacity utilization). Thus, she, if needed, she could perform strenuous tasks she may face (functional reserve). In contrast, a 67-year old gentleman with a history of COPD and hypertension who lives alone in a 3rd floor apartment and he gets very little exercise (Figure 4B). He devloped pneumonia and septic shock 6 months ago during which time he was mechanically ventilated for 3 days. Since his illness, he finds that he becomes “worn out” after bathing, dressing, and geting around his home. He is unable to climb the stairs to his apartment and has to take the elevator. He notes that he gets confused from time to time. He has stopped preparing his own meals because it requires too much effort to walk the two blocks to the grocery store. He has overdrawn his bank account three times in the last six months. His overall functional capacity is low. He is unable to perform strenuous activities (low functional reserve). His routine daily acitivites (funtional performance) require high levels of exertion to perform (high functional capacity utilization).

Figure 4. Comparison of functional status between two patients.

Panel A depicts the functional status of a 35-year old fit woman and Panel B depicts the functional status of a 67-year old sepsis survivor. Note the overall difference in the magnitude of functional capacity. Although functional performance differs slightly between the two, panel B is much closer to falling below the threshold for dependence (red line). The woman in panel A has greater functional reserves, indicating she is capable of performing strenuous tasks. In contrast, the man in panel B has very little reserve. Moreover, he is using much more of his functional capacity (high functional capacity utilization) and is therefore exerting himself more to perform his daily activities. High levels of exertion are often not sustainable for long periods of time and can lead to a decrease in the frequency or overall cessation of activities needed to live independently.

These two examples highlight the different ends of the functional status spectrum. Their contrast, however, has implications for the design of interventions for survivors of critcial illness. For example, interventions could be designed to augment functional capacity, therefore increasing the functional reserve availble to be used in performing daily activities, removing a potential cause of disability. Likewise, interventions that can minimize functional capacity utilization, such as a motorized scooter, could restore his ability to shop independently, thereby increasing functional performance without chanigng functioanl capacity. Thus, components of functional status should be considered when designing and testing interventions for survivors of critical illness.

Linking Diseases with Impairments and Disabilities

With an understanding of the dynamic components of functional status, we now turn to one final model to that links critical illness with the ability to perform independent activities of daily living. The previous example of the 67-year old gentleman’s functional performance describes how critical illness resulted in his inability to shop for food and manage his finances, activities required for independent living.

Disability, is a state of decreased function associated with a disease, disorder, injury, or other health condition, which in the context on one’s environment is experienced as a difficulty or dependency in performing the activities necessary to interact with one’s environment within the context of one’s socially defined role or roles.38 Thus, because he is unable to perform activities that are considered by society to be necessary for independent living (i.e., shopping and managing money), he is disabled in his activities of daily living.

The most basic activities needed to live independently are called activities of daily living (ADLs). ADLs can be divided hierarchically into basic ADLs (BADLs), instrumental ADLs (IADLs), and mobility activities. BADLs include activities such as bathing, dressing, eating, continence, toileting, and transferring. IADLs include shopping, housekeeping, cooking, using the telephone, managing medications and finances, and using transportation. Mobility activities include moving around one’s home/apartment, moving around outside of one’s home including walking several blocks, travelling outside one’s neighborhood, and travelling outside one’s town.

A number of conceptual models describing how acute illness or injuries can result in impairments and disabilities have been proposed.39–42 One of the most informative of these models is that proposed originally by Nagi in the 1960s, adopted by the World Health Organization in 1980, and subsequently modified by Verbrugge and Jette mid-1990s.39–42 This framework states that diseases, illnesses, and injuries (pathology) lead to anatomical, physiological, mental/cognitive, or emotional abnormalities in body structures and functions (impairments), which in turn lead to the inability to perform physical and cognitive tasks (limitations), which decrease the ability of the patient to perform routine self-care activities (disabilities) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The Disability Process.

This figure illustrates the disability process. Illness and injury (pathology) affect the structure and function of different body systems (impairments) that result in reduced ability to perform physical or mental actions (limitations). When placed into a specific environmental context, these limitations result in the inability to perform socially defined roles and tasks (disability). Above the chevron diagram are the conceptual definitions for each component. Below the chevron diagram is the application of these concepts to a survivor of critical illness.

From Brummel NE, Balas MC, Morandi A, et al. Understanding and reducing disability in older adults following critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1265–75. Adapted from Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994 Jan;38(1):1–14; with permission.

Returning to the previous example of the 67-year old gentleman, he had pneumonia and septic shock (pathologies). As the result of his illness and his ICU care, he was sedated and immobile, when combined with his underlying sepsis and coexisting medical conditions, resulted in structural and functional changes to his muscles and brain (impairments). When he was being discharged from the hospital, he was noted to have muscle weakness, difficulty walking, and resolving delirium. The physical therapist and occupational therapist recommended discharge to inpatient rehabilitation. At the rehabilitation hospital, he was noted to have diminished handgrip strength and slow walking speed. His performance on cognitive testing was also below average for his age (limitations). Now that he has returned home, he has difficulty bathing, dressing, and moving around his home. He is no longer able to shop for food and has difficulty managing his finances (disabilities).

That impairments and limitations are related to, but not synonymous with, disabilities has implications for selection of outcomes in clinical trials for survivors of critical illness. For example, though designed to improve muscle weakness, an randomized trial of early physical and occupational demonstrated less disability among those assigned to the intervention group without improvements in muscle strength.14 Thus, interventional studies should not only consider the effects on impairments and limitations (e.g., muscle weakness and thinking problems) but how the intervention might also affect real world function (e.g., disability). In addition, because disabilities are a product of a person’s abilities and the environment, environmental modifications or other accommodation strategies should be tested to reduce disability after critical illness.

Conclusions

The study of outcomes after critical illness is a new field and wide-ranging knowledge is being generated to describe outcomes after critical illness. A better understanding of conceptual models of outcomes research is needed to move the field forward. Existing outcomes research frameworks may be a useful means by which to study outcomes after critical illness. These frameworks may be used to aid interventional and observational trials in choice of which outcomes to measure and highlight the need to also take into account the effects of the outcomes from related domains. The optimal methods (e.g., timing, methods) for assessing outcomes in critical care research are as yet undefined and in need of further study. Core outcome sets from each of the five outcome domains are needed. Informed by existing models of outcomes domains, functional status, and the disability process, advances in the study of outcomes after critical illness will facilitate the design and conduct of future interventional trials.

KEY POINTS.

Heterogeneity in studies of survivors of critical illness limits knowledge of outcomes. Conceptual models of outcomes developed in other fields can be used to understand better outcomes after critical illness.

Outcomes after critical illness fall into five distinct, but interrelated, domains.

Knowledge of the four components that comprise functional status (functional capacity, functional performance, functional reserve, and functional capacity utilization) serves as a foundation for understanding the dynamics of functional outcomes after critical illness.

Impairments and disabilities are related, but not synonymous.

Careful consideration of these models is needed when selecting an outcome of interest for clinical trials and observational studies.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

I have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Iwashyna TJ, Speelmon EC. Advancing a Third Revolution in Critical Care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:782–3. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201603-0619ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turnbull AE, Rabiee A, Davis WE, et al. Outcome Measurement in ICU Survivorship Research From 1970 to 2013: A Scoping Review of 425 Publications. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1267–77. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Davis WE, et al. Perspectives of survivors, families and researchers on key outcomes for research in acute respiratory failure. Thorax. 2018;73:7–12. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, et al. Core Outcome Measures for Clinical Research in Acute Respiratory Failure Survivors. An International Modified Delphi Consensus Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1122–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leidy NK. Functional status and the forward progress of merry-go-rounds: toward a coherent analytical framework. Nurs Res. 1994;43:196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langerud AK, Rustoen T, Smastuen MC, Kongsgaard U, Stubhaug A. Intensive care survivor-reported symptoms: a longitudinal study of survivors’ symptoms. Nurs Crit Care. 2018;23:48–54. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eakin MN, Patel Y, Mendez-Tellez P, Dinglas VD, Needham DM, Turnbull AE. Patients’ Outcomes After Acute Respiratory Failure: A Qualitative Study With the PROMIS Framework. Am J Crit Care. 2017;26:456–65. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2017834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill TM, Feinstein AR. A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA. 1994;272:619–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuthbertson BH, Scott J, Strachan M, Kilonzo M, Vale L. Quality of life before and after intensive care. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:332–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.04109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuthbertson BH, Rattray J, Campbell MK, et al. The PRaCTICaL study of nurse led, intensive care follow-up programmes for improving long term outcomes from critical illness: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b3723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott D, McKinley S, Alison J, et al. Health-related quality of life and physical recovery after a critical illness: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial of a home-based physical rehabilitation program. Crit Care. 2011;15:R142. doi: 10.1186/cc10265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson JC, Girard TD, Gordon SM, et al. Long-term cognitive and psychological outcomes in the awakening and breathing controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:183–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0442OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson JC, Ely EW, Morey MC, et al. Cognitive and physical rehabilitation of intensive care unit survivors: results of the RETURN randomized controlled pilot investigation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1088–97. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182373115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:369–79. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brummel NE, Girard TD, Ely EW, et al. Feasibility and safety of early combined cognitive and physical therapy for critically ill medical and surgical patients: the Activity and Cognitive Therapy in ICU (ACT-ICU) trial. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:370–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3136-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brummel NE, Balas MC, Morandi A, Ferrante LE, Gill TM, Ely EW. Understanding and reducing disability in older adults following critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1265–75. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers LS, Gill TM. Functional Trajectories Among Older Persons Before and After Critical Illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrante LE, Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Leo-Summers LS, Gill TM. Factors Associated with Functional Recovery among Older Intensive Care Unit Survivors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:299–307. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1256OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Pope D, Orme JF, Bigler ED, Larson LV. Neuropsychological sequelae and impaired health status in survivors of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:50–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9708059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Collingridge D, Parkinson RB, Chan KJ, Orme JF., Jr Two-year cognitive, emotional, and quality-of-life outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:340–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-763OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Morris PE, et al. Physical and cognitive performance of patients with acute lung injury 1 year after initial trophic versus full enteral feeding. EDEN trial follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:567–76. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0651OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Needham DM, Wozniak AW, Hough CL, et al. Risk factors for physical impairment after acute lung injury in a national, multicenter study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1214–24. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201401-0158OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan E, Dowdy DW, Colantuoni E, et al. Physical complications in acute lung injury survivors: a two-year longitudinal prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:849–59. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moss M, Nordon-Craft A, Malone D, et al. A Randomized Trial of an Intensive Physical Therapy Program for Acute Respiratory Failure Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-1039OC. ePub December 10, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M, et al. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1377–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31637-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris PE, Berry MJ, Files DC, et al. Standardized Rehabilitation and Hospital Length of Stay Among Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2694–702. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peel C, Sawyer Baker P, Roth DL, Brown CJ, Brodner EV, Allman RM. Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Phys Ther. 2005;85:1008–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychological function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323–9. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leonardi M, Bickenbach J, Ustun TB, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S Consortium M. The definition of disability: what is in a name? Lancet. 2006;368:1219–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagi SZ. A Study in the Evaluation of Disability and Rehabilitation Potential: Concepts, Methods, and Procedures. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1964;54:1568–79. doi: 10.2105/ajph.54.9.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO. International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps. Genva: World Health Organization; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization T. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability, and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jette AM. Toward a common language for function, disability, and health. Phys Ther. 2006;86:726–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]