Abstract

The management of in-stent restenosis continues to be a common challenge in modern interventional cardiology. Drug-eluting stents have emerged to be an effective treatment following bare-metal stent in-stent restenosis as compared with drug-coated balloon angioplasty and repeat bare-metal stenting. The addition of another metallic layer is however undesirable and may limit further treatment options. In the last few years, everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffolds have become available in treating native coronary artery disease with complete hydrolysis into water and carbon dioxide within 3–5 years. To exploit this property, we successfully used it to manage a case of drug-eluting stent in-stent restenosis from a previously under-expanded stent as demonstrated in this case. Small registry series have also recently been published supporting favorable outcomes with this approach. To the best of our knowledge, this case has the longest optical coherence tomography follow-up beyond 3 years.

<Learning objective: The dedicated dual-layer OPN NC balloon (Schwager Medica, Winterthur, Switzerland) could be used in the under-expanded metallic stent that is not overcome by conventional non-compliant balloons as demonstrated in our case. The application of bioresorbable vascular scaffold in drug-eluting stent in-stent restenosis has satisfactory medium- to long-term clinical outcome. The 3-year follow-up intracoronary study demonstrated complete tissue coverage of the scaffold. Complete bioresorption of the scaffold, by hydrolysis into carbon dioxide and water, takes approximately 3–5 years, thus avoiding another layer of metallic cage.>

Keywords: Bioresorbable vascular scaffold, In-stent restenosis, High pressure balloon

Introduction

From the early days of plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA), restenosis has been the “Achille’s heel” of percutaneous coronary revascularization. Bare-metal stents (BMS) have reported restenosis rates of up to 20% within the first year of treatment [1], [2]. Drug-eluting stents (DES) were designed with the intention of reducing the high in-stent restenosis (ISR) rates associated with neointimal proliferation and have proven to be effective both angiographically and clinically, particularly in high-risk patients [3]. Restenosis has not however been abolished and ISR when encountered is a difficult iatrogenic clinical problem to manage. Currently, DES and drug-coated balloon (DCB) are both considered to be the main treatment modalities for ISR with drawbacks from each modality, such as an additional layer of metal and higher restenosis rate, respectively [4]. Recently, bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) have been demonstrated to be used successfully and safely in ISR lesions [5]. The property of temporary scaffolding resolves the issue of a permanent layer of metal as well as improved acute gain compared to balloon angioplasty alone. This case report will demonstrate a successful use of BVS in an ISR lesion with long-term optical coherence tomography (OCT) follow-up beyond 3 years.

Case report

A 57-year-old man underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to the mid left anterior descending (LAD) artery with a 2.25 × 32 mm everolimus-eluting stent for unstable angina. Post-dilation of the proximal stent segment however was unsuccessful despite multiple inflations with a 2.75 × 10 mm high-pressure non-compliant balloon to 30 atm. There was a residual 30% diameter stenosis post-PCI (Fig. 1a). This patient subsequently represented with exertional angina 1 year later and relook coronary angiography was performed.

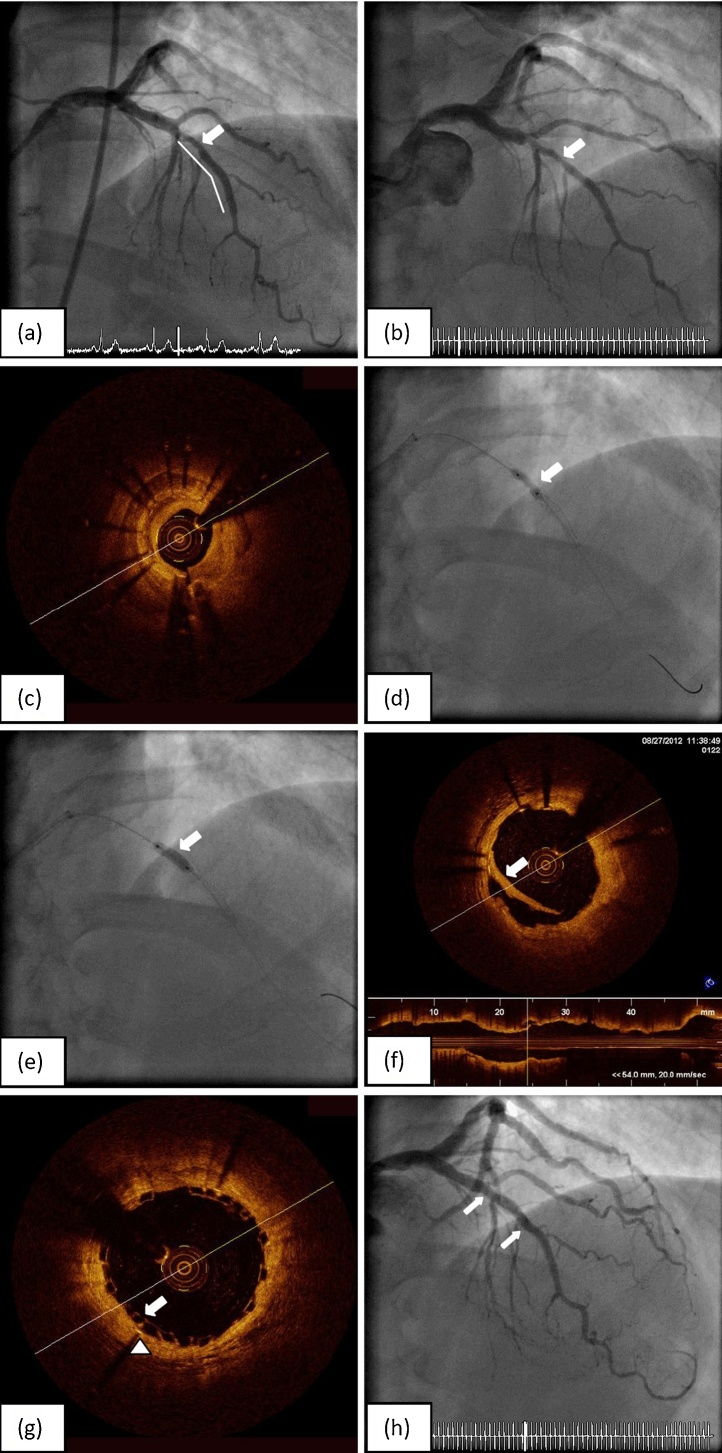

Fig. 1.

(a) Previous final angiography from mid left anterior descending artery stenting (solid line) showed under-expanded stent segment (arrow). (b) Diagnostic coronary angiography on this occasion demonstrated significant in-stent restenosis at the under-expanded stent segment (arrow). (c) Optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirmed significant in-stent restenosis at the under-expanded section. (d) Multiple balloon inflation failed to open up the tight stenosis (arrow). (e) The 3.0 × 10 mm OPN NC balloon was able to overcome the under-expanded area at 35 atm. (f) Repeated OCT confirmed adequate expansion of the stent at stenosis site with a dissection flap (arrow). (g) OCT following ABSORB bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) implantation demonstrated satisfactory apposition of BVS scaffolds (arrow) with the previously deployed metal stent (arrow head). (h) Final angiography showed satisfactory results (arrows indicated both ends of scaffold marker).

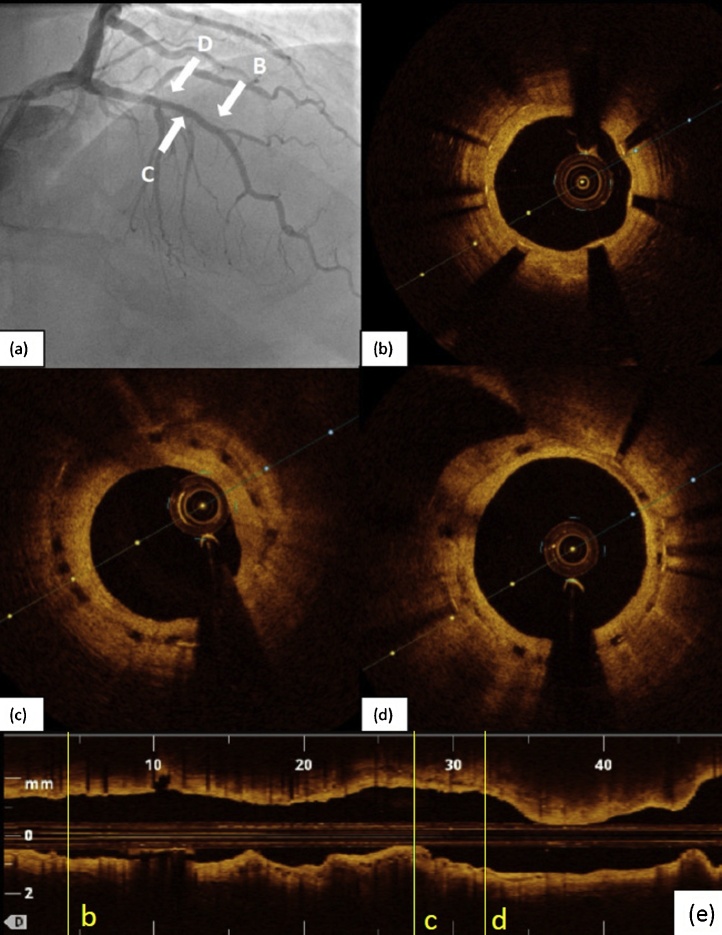

Repeat coronary angiography via a right radial approach showed a focal 80% diameter stenosis of the under-expanded segment of the mid LAD stent (Fig. 1b). A 6 Fr Ikari left 3.5 guiding catheter was used to selectively engage the left main coronary artery ostium. This ISR segment was interrogated with a C7 DragonFly (St Jude Medical, St Paul, MN, USA) OCT catheter and confirmed significant ISR due to significant neointimal hyperplasia and underlying suboptimal DES expansion (Fig. 1c). A minimal luminal area (MLA) of 1.7 mm2 was noted with the distal reference vessel diameter measuring 2.75 mm. Predilation of the lesion was performed using a 2.5 × 15 mm and subsequently a 2.75 × 8 mm non-compliant balloon up to 24 atm, but both balloons failed to open up the stenotic segment (Fig. 1d). A 3 × 10 mm cutting balloon could not cross the lesion. Finally, a high-pressure 3 × 10 mm OPN NC balloon (Schwager Medica, Winterthur, Switzerland) was able to successfully open up the lesion at 35 atm (Fig. 1e). Repeat OCT interrogation showed in-stent neointimal dissection and an in-stent luminal diameter of 2.8–2.9 mm (Fig. 1f). We decided to treat this lesion with a 3 × 18 mm ABSORB bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS; Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA); the BVS was deployed at 16 atm. This was followed by post-dilatation using a 3.25 × 15 mm NC balloon up to 20 atm. Final OCT showed satisfactory scaffold apposition to the metallic stent and an MLA of 6.5 mm2 (Fig. 1g,h). Standard one-year duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy was prescribed. The patient remained well until 3.5 years later when he represented with angina due to an obtuse marginal artery stenosis. Magnetic resonance imaging-perfusion and fractional flow reserve (FFR) studies confirmed this as culprit and it was treated with a DES. Coincidentally, coronary angiography demonstrated mild to moderate angiographic in-scaffold restenosis of the LAD (Fig. 2a). Repeat OCT showed complete tissue coverage of the scaffold struts and “in-scaffold” neointima hyperplasia with an MLA of 3.16 mm2 (Fig. 2b–d). Despite a significant 51% late-lumen loss from 6.5 mm2, FFR measured 0.95, suggesting a non-physiologically significant lesion. No further intervention was therefore performed. Of note, There was a significant change in mean luminal area in the BVS treated ISR segment, arbitrarily defined from the beginning of the BVS site to 2 mm distal to the BVS segment (7.7 mm2–4.2 mm2, Δ = −45%; p < 0.001, t-test) compared to the DES segment (4.2 mm2–3.8 mm2, Δ = −9.5%; p = 0.213) that did not have significant ISR (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

(a) Coronary angiography 42 months later demonstrated mild in-stent stenosis (41% by quantitative coronary analysis) with optical coherence tomography (OCT) sections taken at various places. (b) Distal to the bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) showed metallic stent with neointimal hyperplasia. (c & d) OCT section at BVS segment with visible residual scaffold well covered with neointimal hyperplasia; a 51% late loss was noted with the minimal luminal area of 3.16 mm2, however, this was not physiologically significant. (e) The longitudinal L-mode OCT image with markers correspond to the cross-section images taken from (b) to (d).

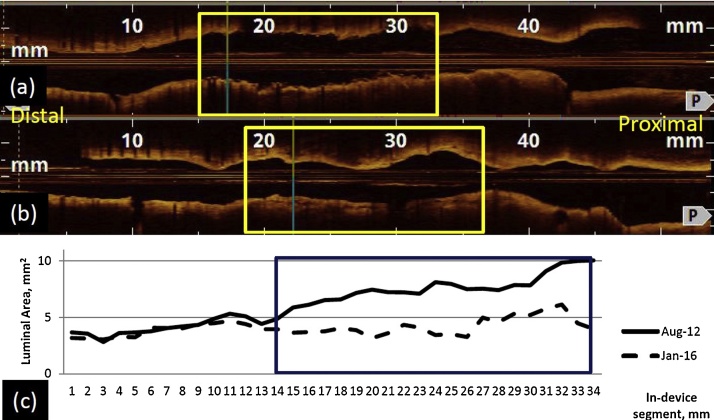

Fig. 3.

(a & b) The longitudinal L-mode optical coherence tomography images from the study in 2012 and 2016, respectively. The boxed area represents the in-stent restenosis (ISR) segment treated with a bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS). (c) A line graph to show luminal area measured at 1-mm intervals from the beginning of BVS to end of drug-eluting stent with the boxed area represents the ISR segment treated with a BVS.

Discussion

We report a clinically significant ISR from a previously under-expanded DES managed successfully by the ABSORB BVS. Stent under-expansion is associated with the development of ISR in DES especially with longer lengths [6]. During the index procedure of stent implantation, stent expansion was unsatisfactory despite the use of multiple high-pressure non-compliant balloon inflations to 30 atm; this value is well over the rated burst pressure and the limit of most conventional inflators. The OPN NC High-Pressure Balloon, however, is a twin-layered non-compliant balloon with a rated-burst pressure at 35 atm and this allowed for overcoming the incompletely expanded stent segment at 35 atm in our case. Repeat OCT assessment then revealed a satisfactory luminal diameter of 3.0 mm with the previously well-apposed everolimus-eluting stent. In order to avoid further layering of metal, we decided to implant an ABSORB BVS, a balloon-expandable everolimus-eluting scaffold consisting of a poly-l-lactide polymer coated with a thin layer of 1:1 poly-d,l-lactide that serves as the drug-reservoir. Bioresorption of the scaffold occurs by hydrolysis into carbon dioxide and water in approximately 3–5 years [7]. The treatment of ISR has been problematic with current recommendation of new-generation DES or DCB [8]. The addition of further permanent layers of metallic stents within an in-stent restenotic segment is an unattractive method of addressing this issue. DCB, while a preferred approach to avoid further layering of metal in the artery, is associated with higher clinical and angiographic restenosis rates, probably due to its inability to achieve maximum acute luminal gain [4]. To address the above disadvantages, BVS provides temporary vascular scaffolding to maximize the acute luminal gain and does not add an additional permanent layer of metal. Moscarella et al. recently published a multi-center experience in treating ISR with BVS. The reported annual device-orientated composite end point (cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, ischemic-driven target lesion revascularization) of 9.1% at 1 year was comparable to the everolimus-eluting stent arm of the RIBS IV/V trial (8.8%), which compared the efficacy of everolimus-eluting stent and paclitaxel-eluting balloon in patients with ISR [4], [5]. These results support the clinical safety and efficacy in using a temporary scaffolding to treat ISR lesions.

In the follow-up angiography, there is an observed non-physiologically significant 51% loss of MLA at the DES ISR site treated with BVS. When comparing with the DES segment without initial significant ISR, there is a significant reduction in mean luminal area in the DES ISR segment treated with a BVS (45% vs 9%; p < 0.001) after 3.5 years. This observation was interesting as the 36-months intravascular ultrasound results in the ABSORB first in man trial showed enlargement of mean luminal area in a native vessel. The OCT results were available in a smaller number of patients and showed reduction of mean luminal area (7.72–6.09 mm2) on 3 years follow-up. However, there were no significant changes at 1 year–3 years (6.01–6.09 mm2; p = ns) [9]. At the present time, it is unclear if the unexpected higher mean luminal area reduction in DES ISR segment treated with BVS implantation is related to the presence of an existing metallic stent. Further studies may help confirm this observation as well as comparing to other modalities such as a DCB.

In conclusion, we demonstrated successful use of the BVS in treating an under-expanded DES ISR with a dedicated high pressure balloon. This case also supports a satisfactory long-term clinical outcome with follow-up intracoronary study demonstrating complete tissue coverage of the scaffold struts beyond 3 years.

Conflict of interest

Nil for all authors.

Contributor Information

Michael Liang, Email: liang.michael.mc@alexandrahealth.com.sg.

Adrian F. Low, Email: adrian_low@nuhs.edu.sg.

References

- 1.Abizaid A.S., Mintz G.S., Mehran R., Abizaid A., Lansky A.J., Pichard A.D. Long-term follow-up after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty was not performed based on intravascular ultrasound findings: importance of lumen dimensions. Circulation. 1999;100:256–261. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yokoya K., Takatsu H., Suzuki T., Hosokawa H., Ojio S., Matsubara T. Process of progression of coronary artery lesions from mild or moderate stenosis to moderate or severe stenosis: a study based on four serial coronary arteriograms per year. Circulation. 1999;100:903–909. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone G.W., Ellis S.G., Cox D.A., Hermiller J., O’Shaughnessy C., Mann J.T. One-year clinical results with the slow-release, polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting TAXUS stent: the TAXUS-IV trial. Circulation. 2004;109:1942–1947. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127110.49192.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alfonso F., Perez-Vizcayno M.J., Garcia Del Blanco B., Garcia-Touchard A., Masotti M., Lopez-Minguez J.R. Comparison of the efficacy of everolimus-eluting stents versus drug-eluting balloons in patients with in-stent restenosis (from the RIBS IV and V randomized clinical trials) Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moscarella E., Ielasi A., Granata F., Coscarelli S., Stabile E., Latib A. Long-term clinical outcomes after bioresorbable vascular scaffold implantation for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis: a multicenter Italian experience. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e003148. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang S.J., Mintz G.S., Park D.W., Lee S.W., Kim Y.H., Whan Lee C. Mechanisms of in-stent restenosis after drug-eluting stent implantation: intravascular ultrasound analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:9–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.940320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onuma Y., Ormiston J., Serruys P.W. Bioresorbable scaffold technologies. Circ J. 2011;75:509–520. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Windecker S., Kolh P., Alfonso F., Collet J.P., Cremer J., Falk V. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the task force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serruys P.W., Onuma Y., Garcia-Garcia H.M., Muramatsu T., van Geuns R.J., de Bruyne B. Dynamics of vessel wall changes following the implantation of the absorb everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffold: a multi-imaging modality study at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months. EuroIntervention. 2014;9:1271–1284. doi: 10.4244/EIJV9I11A217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]