Abstract

Hospitals have a pivotal role in reducing health inequities for indigenous people and other marginalised groups, argue Anna Matheson and colleagues

Hospitals have evolved to become integral and dominant components of health systems, although their functions, organisation, size, degree of centralisation, and resourcing varies across countries. Despite this diversity, hospitals are generally focused on providing services for sick people rather than prevention. Although many have shown the capacity to quickly adopt new technologies, especially for diagnosing and managing illness, achieving institutional change to tackle the systemic causes of health inequities has proved much more difficult.1

We argue that the actions of hospitals contribute to health inequities. This is important given that hospitals hold an inordinate share of power, resources, and influence within health and community systems—while primary care and prevention are consistently undervalued and underfunded. We draw on four opportunistically selected country case examples to show the role that hospitals can play in overcoming systemic barriers to health equity. Each example highlights health sector actions taken for particular population groups: women and children in Pakistan and Rwanda and the indigenous peoples of Australia and New Zealand.

Reorienting systems to the local: evidence of health inequities

Reorienting health services to be more responsive to local community realities is not new. The promise of primary care has been to bring services closer to people and to alleviate the need for hospital services.2 However, health inequities persist in access to, and use of, primary care as well as hospital services, with inequity magnified as people move through the health system. Similarly, multiple determinants of health such as housing, education, and income as well as less visible causes such as social connectedness, community participation, government policy processes, and corporate actions compound inequity for the same groups disadvantaged through health systems.3 Not surprisingly, illness in individuals also compounds over time, often leading to multimorbidities.4

Local compounding describes how inequities are magnified for different social groups through complex social processes.5 The emergence of inequity is explained by non-linearity and the concept of “sensitivity to initial conditions,” whereby initial conditions are reinforced and interactions can have disproportionate effects. Complex systems thinking is increasingly seen as necessary to make sense of health systems.6 7 It becomes even more useful when the wider social systems within which health systems are embedded are also conceptualised as complex. Understanding the underlying behaviour of complex systemscan identify actions that are likely to shift community systems from their existing states and stop prevailing health outcomes being repeatedly reproduced.8

Measuring, uncovering, and acting on health inequities

Social action focused on a geographical community can potentially capture many local factors that influence health, especially those associated with poverty.9 However, for some social groups other systemic factors compound geographical and socioeconomic effects. Indigeneity; gender; age; ethnic, religious, or cultural affiliation; disability; or being a new migrant or refugee are characteristics of groups likely to experience health inequities.

In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a life expectancy 10 to 17 years less than other Australians. For Māori in New Zealand the difference in life expectancy compared with non-Māori is about seven years. In both countries, an important contributor to these differences is unequal access to healthcare at all levels of service provision.10 11 12 13 14 In Pakistan, discrimination against women, including insufficient access to maternal, child, and infant services are major reasons for high rates of infant mortality.15 16 Rwanda, on the other hand, has substantially reduced its infant mortality and seen improvements in other health indicators, and has begun to make progress on gender inequality.17 18

The performance of health systems is usually measured by hospital admissions, population mortality, and disease incidence. However unmet need, an important driver of health inequities, is poorly measured.19 For some countries, particularly low and middle income, getting good health data of any kind is a challenge, but even in high income countries it is difficult to get good data on all population groups and context specific causes of health outcomes.

The example of the People’s Primary Healthcare Initiative (box 1) shows how even a small amount of local knowledge can inform more effective social actions. This fact is well known within some disciplines20 and increasingly recognised in others.21 The non-linear relation between emergent phenomena (such as inequalities by social group) and initial conditions means that pathways to achieving change, and therefore the effects of intervention, will vary between communities. The challenge is how to systematically gather and feed back local and contextual knowledge to inform how services are designed and delivered, and to empower and adapt to the circumstances of patients and communities.

Box 1. People’s Primary Healthcare Initiative, Pakistan.

The People’s Primary Healthcare Initiative (PPHI) is a not-for-profit organisation set up to contract out services in response to high maternal and infant mortality in rural Sindh, Pakistan. The hospitals in PPHI are located mostly in remote, poor, rural areas.

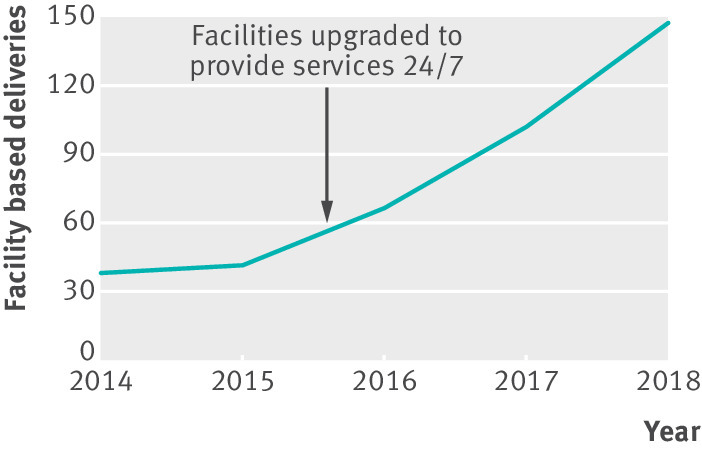

The PPHI’s focus was to improve service quality by following the international framework of quality of care for maternal and newborn health services. Despite hospitals providing a high quality service, the number of facility based deliveries (a key indicator in adverse outcomes of pregnancy) did not increase significantly. Research by the PPHI identified that the hours of operation and the absence of a female healthcare provider were barriers to use of its services. Consequently, 280 health facilities were upgraded to operate 24 hours a day with a female medical officer on site.

Potential—The PPHI facilities providing normal vaginal delivery 24 hours a day now conduct a much higher number of deliveries than when they operated for eight hours a day, 144 896 in 2017-18 versus 37 873 in 2013-2014 (fig 1).

Challenges—Despite the changes progress has been slow and many women still deliver at home without skilled care, especially in low socioeconomic areas.16 An ongoing challenge is limited evidence on patient and community perspectives of what services are needed and the best ways for those services to be delivered.

Fig 1.

Number of deliveries at PPHI Sindh facilities

Good quantitative data on social groups are clearly important, especially for monitoring and enabling accountability.22 Equally important are methods that can capture and respond to less obvious features of populations and their contexts. Working in partnership with patients and communities and using adaptive and participatory methods, such as codesign to incorporate local voices and experimentation and prototyping to explore local solutions, can uncover and address unmet need. Furthermore, strengthening the way that communities are organised and amplifying community voice can help dismantle systemic barriers. Illuminating and communicating how determinants are experienced locally and strengthening community agency can help avoid harms to health caused by the decisions and actions of other societal actors such as corporations, driven by their pursuit for profit, and public and policy organisations using ineffective methods and strategies.

Institutional racism: a systemic pathway to inequity

Institutional racism has been clearly evidenced for indigenous populations; colonisation has shaped the policies, structures, governance, and practices of public institutions, including hospitals, to respond poorly to the needs and rights of indigenous people.23 24 25 26 Institutional racism also contributes to systemic societal exclusion and compounds the already devastating effects of poverty. In Australia and New Zealand, institutional racism has been gaining visibility through better identification, measurement, and articulation (boxes 2 and 3). In Pakistan and Rwanda it still has low visibility and the United Nations has highlighted it as a human rights concern.31

Box 2. Beginning the transformation of institutional racism—Australia.

An external assessment tool to measure institutional racism in hospitals has been developed using publicly available data and a matrix of five key indicators: inclusion in governance; policy implementation; service delivery; employment; and financial accountability. The 2014 case study of Cairns and Hinterland Hospital and Health Service (CHHHS) used this matrix and found high levels of institutional racism.27

Potential—The latest annual report of CHHHS shows the beginnings of transformation, including appointment of an Indigenous Australian to the hospital board; founding an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Community Consultation Committee; employing an executive director of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health; and reporting data on discharges against medical advice and potentially preventable admissions. This shows that identifying institutional racism can lead to action.

Challenges —Measuring the effect of the changes requires time, but using proxies, such as data on discharge against medical advice, will help. Maintaining momentum is the main challenge for this hospital. Rolling out the assessment and reporting of institutional racism, and implementing strategies to tackle it across the Australian health system, is the challenge for the country.

Box 3. Systems change through cultural safety education and translational practice—New Zealand.

Cultural safety is a process of creating institutional culture change to reduce health inequities between Māori and non-Māori through education and training. Cultural safety shifts responsibility for confronting systemic causes of inequity onto institutions and those who work within them.28 Despite its value being widely recognised, one study29 identified only nine (out of 20) district health boards required employees to undertake cultural safety training, with no data available on numbers who had done the training.

Potential —Creating culturally safe organisations through raising consciousness and redistributing power provides a way to transform institutional practices to be more responsive to diverse local populations. Along with other enabling mechanisms such as the Treaty of Waitangi, the founding document of colonial New Zealand,30 colonisation processes can potentially be redressed.

Challenges —Cultural safety requires consciously considering the transfer of power and resources. This is probably why it has not yet become integral to health systems. Although some health professionals have embraced it, implementation within management and policy leadership has a long way to go.

Although partial successes have been shown in some areas, such as workforce discrimination,32 “whole system” attempts by hospitals to tackle institutional racism are rare.24 33 In Australia, it is early days in creating greater awareness and acceptance. While in New Zealand, one long recognised approach to promote cultural responsiveness and produce system change within hospitals has not been widely implemented or used to redistribute power, as was its intent (box 3).

Investing effectively to achieve shared health goals

Creating culturally safe services, decentralising to empower local communities, or setting social justice goals can be undermined by less obvious relationships and processes. In Rwanda, where health gains are being made, political will for championing health equity has been instrumental (box 4). Achieving political will often requires many years of tumultuous social and political struggle, and even when this will is able to be sustained it remains prone to subversion by the actions of national and global organisations.36 Rwanda, for example, has historically been reliant on fragmented and uncertain donor funding for the health system, constraining cohesive, longer term planning to meet health goals.

Box 4. Political will and multiple actions to tackle health inequity—Rwanda.

Since the 1994 genocide, Rwanda has renewed motivation to reduce discrimination and inequality and has embarked on an integrationist path to civic identity.34 35 Multiple actions have been taken to improve health equity, including community outreach of clinical services; home based care practitioners providing cancer care at the village level; community health workers; community based health insurance, enabling the most vulnerable to access care; and social protection programmes, ensuring health related costs do not result in catastrophic circumstances for families.

Potential—Large gains have been seen for several health indicators, including infant mortality.17 18 An overarching facilitating factor has been the prevailing political will within Rwanda to tackle health inequities.

Challenges —Limited infrastructure is a critical barrier. For example, impassable rural roads limit access by outreach and ambulance services. Affordability and health literacy also affect access. Fragile health sector funding reliant on donor and development partners risks the sustainability of services.

Precarious funding and unresponsive investment strategies between different parts of the health system also affect communities. For example, uncertain funding and short term contracts have weakened community based Māori health providers who have facilitated access for Māori to hospital services for many years.37 This vulnerability is exacerbated by pressures from providing unfunded services in response to previously unrecognised need encountered in the community as well as a competitive funding environment that degrades trust and impedes collective community action on shared goals.

Hospitals must act as facilitators

The health system is one of the determinants of health. Moreover, there is considerable evidence that hospitals, and the health systems they are embedded within, contribute to health inequities. Whereas primary and community based health services are likely to have explicit goals of addressing health inequity and prioritising local community needs, hospitals have been slower to adapt and respond effectively to the circumstances of indigenous people and other marginalised population groups such as poor people. Overcoming the institutional inertia of hospitals is important because their power and status makes them uniquely positioned to influence the rest of the health system, including how money is distributed between prevention and primary and acute care.

Some actions are clear for hospitals, and those who make decisions about hospitals, to contribute to improving health equity. Firstly, health equity needs to be a fundamental and shared goal of the health system. Hospitals can unashamedly exploit their pivotal role to champion and facilitate shared actions with health and other sectors. They can also reflect on how their own organisational decisions affect the circumstances of local populations, especially through employment and procurement practices.

Secondly, they can improve their knowledge of local populations with more appropriate data and information, including ways to ensure accountability on equity. This means collecting comprehensive information on all population groups that hospitals serve. It also means uncovering key factors that are harder to identify and measure, such as unmet need and institutional racism.

Thirdly, hospitals can better respond and adapt to local populations, recognising their agency in producing health outcomes and their effect on people’s lives. They can do this by empowering and incentivising the workforce to identify detrimental living conditions or lifestyle factors among inpatients. In coordination with primary care and other relevant sectors, they can support and follow up patients back in the community. Hospitals can normalise community participation that promotes real power sharing and the inclusion of community voice through codesigning services, representation in leadership, and cross-sector advocacy. Moreover, the education and training of the entire workforce, especially leaders and decision makers, needs a rethink to ensure systemic barriers are consciously considered.

Finally, hospitals can be mindful of the unintended, but predictable, consequences of their actions on health equity. For example, the potentially counterproductive behaviours that targets might incentivise, and how other policy actions might create perverse incentives, such as rewarding volume in hospital admissions inadvertently growing hospitals’ share of health budgets. Furthermore, they should look at the way that funding is delivered and managed to ensure community trust is maintained and that resources can be aligned to achieve shared goals.

None of this is new. The Ottawa charter recognised the need to reorient health services more than 30 years ago. However, implementation has often been piecemeal and lacked the close, responsive, and often challenging local relationships required for the meaningful sharing of information (including evidence), power, and resources. A shift in collective thinking towards whole systems is necessary to enable effective action on both emerging and longstanding health inequities. Bold leadership is needed to recognise complex causes and to implement strategies to transform health and community systems to achieve better health for all.

Key messages.

Health inequities result from complex causes that compound locally—with unmet need and institutional racism important drivers

Hospitals have been slow to respond to the circumstances of indigenous people and other marginalised population groups

Hospitals have a pivotal role in tackling health equity as they hold an inordinate share of power, resources, and influence compared with primary care and prevention

Hospitals can facilitate the reorientation of health by identifying and addressing systemic causes of inequity within their own walls and normalising true community participation

Bold leadership is needed to transform health systems to achieve better health for all

Contributors and sources: This article resulted from a Salzburg Global Seminar on building healthy communities: the role of hospitals. AM, AV, IK, and DN were participants at the seminar, while CB, LEL, and ZD are colleagues. AM wrote the first and subsequent drafts of the article and coordinated the input of the coauthors. CB, AV, LEL, and IK contributed to the arguments made in the article and edited and commented on drafts. DN, IK, ZD, LEL, and CB contributed the country case examples. Thanks also to reviewers of earlier drafts for their suggestions for improvement.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series from the Salzburg Global Seminar on building healthy communities: the role of hospitals. Open access fees were funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The BMJ peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish the article with no involvement from the foundation.

References

- 1. McKee M, Healy J. The role of the hospital in a changing environment. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:803-10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Starfield B. Primary care: an increasingly important contributor to effectiveness, equity, and efficiency of health services. SESPAS report 2012. Gac Sanit 2012;26(Suppl 1):20-6. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S, Commission on Social Determinants of Health Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 2008;372:1661-9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Katikireddi SV, Skivington K, Leyland AH, Hunt K, Mercer SW. The contribution of risk factors to socioeconomic inequalities in multimorbidity across the lifecourse: a longitudinal analysis of the Twenty-07 cohort. BMC Med 2017;15:152. 10.1186/s12916-017-0913-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tugwell P, de Savigny D, Hawker G, et al. Health policy: applying clinical epidemiological methods to health equity: the equity effectiveness loop. BMJ 2006;332:358 10.1136/bmj.332.7537.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braithwaite J. Changing how we think about healthcare improvement. BMJ 2018;361:k2014. 10.1136/bmj.k2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med 2018;16:95. 10.1186/s12916-018-1089-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matheson A. Reducing social inequalities in obesity: complexity and power relationships. J Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38:826-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hosseinpoor AR, Bergen N. Area-based units of analysis for strengthening health inequality monitoring. Bull WHO 2016;94:856-8. 10.2471/BLT.15.165266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. AIHW Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease—Australian facts: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Cardiovascular, diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. AIHW Access to health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12. AIHW Better cardiac care measures for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: second national report 2016. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ministry of Health Annual update of key results 2015/16: New Zealand Health Survey. Ministry of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ministry of Health Tatau Kahukura: Māori health chart book 2015. 3rd ed Ministry of Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malik SM, Ashraf N. Equity in the use of public services for mother and newborn child health care in Pakistan: a utilization incidence analysis. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:120. 10.1186/s12939-016-0405-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zaidi S, Riaz A, Rabbani F, et al. Can contracted out health facilities improve access, equity, and quality of maternal and newborn health services? Evidence from Pakistan. Health Res Policy Syst 2015;13(Suppl 1):54. 10.1186/s12961-015-0041-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomson DR, Amoroso C, Atwood S, et al. Impact of a health system strengthening intervention on maternal and child health outputs and outcomes in rural Rwanda 2005-2010. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000674. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Condo J, Mugeni C, Naughton B, et al. Rwanda’s evolving community health worker system: a qualitative assessment of client and provider perspectives. Hum Resour Health 2014;12:71. 10.1186/1478-4491-12-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robson B, Harris R. Hauora: Māori standards of health IV. A study of the years 2000-2005 Wellington. Te Ropu Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pomare, University of Otago, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract 2006;7:312-23. 10.1177/1524839906289376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bardosh KL, Ryan SJ, Ebi K, Welburn S, Singer B. Addressing vulnerability, building resilience: community-based adaptation to vector-borne diseases in the context of global change. Infect Dis Poverty 2017;6:166. 10.1186/s40249-017-0375-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cookson R, Asaria M, Ali S, Shaw R, Doran T, Goldblatt P. Health equity monitoring for healthcare quality assurance. Soc Sci Med 2018;198:148-56. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Came H. Sites of institutional racism in public health policy making in New Zealand. Soc Sci Med 2014;106:214-20. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moore SP, Green AC, Bray F, et al. Survival disparities in Australia: an analysis of patterns of care and comorbidities among indigenous and non-indigenous cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2014;14:517. 10.1186/1471-2407-14-517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health 2000;90:1212-5. 10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carmichael S, Hamilton C. Black power; the politics of liberation in America. Random House, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marrie A, Marrie H. A matrix for identifying, measuring and monitoring institutional racism within public hospitals and health services. Bukal Consultancy Services, 2014.

- 28. Papps E, Ramsden I. Cultural safety in nursing: the New Zealand experience. Int J Qual Health Care 1996;8:491-7. 10.1093/intqhc/8.5.491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sheridan NF, Kenealy TW, Connolly MJ, et al. Health equity in the New Zealand health care system: a national survey. Int J Equity Health 2011;10:45. 10.1186/1475-9276-10-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Orange C. The treaty of Waitangi. Bridget Williams Books, 2011. 10.7810/9781877242489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.General Assembly, Third Committee. United Nations. UN Report GA/SHC/4115. 2014.https://www.un.org/press/en/2014/gashc4115.doc.htm

- 32. Priest N, Esmail A, Kline R, Rao M, Coghill Y, Williams DR. Promoting equality for ethnic minority NHS staff—what works? BMJ 2015;351:h3297. 10.1136/bmj.h3297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hill S, Sarfati D, Robson B, Blakely T. Indigenous inequalities in cancer: what role for health care? ANZ J Surg 2013;83:36-41. 10.1111/ans.12041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vandeginste S. Governing ethnicity after genocide: ethnic amnesia in Rwanda versus ethnic power-sharing in Burundi. J East Afr Stud 2014;8:263-77. 10.1080/17531055.2014.891784 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ingelaere B. Peasants, power and ethnicity: a bottom-up perspective on Rwanda’s political transition. Afr Aff (Lond) 2010;109:273-92. 10.1093/afraf/adp090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Birn A-E. Making it politic(al): closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Soc Med 2009;4: 166-82. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Slater T, Matheson A, Davies C, Goodyer C, Holdaway M, Ellison-Loschmann L. The role and potential of community-based cancer care for Māori in Aotearoa/New Zealand. N Z Med J 2016;129:29-38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]