Summary

Lithium-sulfur (Li-S) batteries are an appealing candidate for advanced energy storage systems because of their high theoretical energy density and low cost. However, rapid capacity decay and short cycle life, mainly resulting from polysulfide dissolution, remains a great challenge for practical applications. Herein, we present a metal-organic framework (MOF)-derived Co9S8 array anchored onto a chemical vapor deposition (CVD)-grown three-dimensional graphene foam (Co9S8-3DGF) as an efficient sulfur host for long-life Li-S batteries with good performance. Without polymeric binders, conductive additives, or metallic current collectors, the free-standing Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode achieves a high areal capacity of 10.9 mA hr cm−2 even at a very high sulfur loading (10.4 mg cm−2) and sulfur content (86.9 wt%). These results are attributed to the unique hierarchical nanoarchitecture of Co9S8-3DGF/S. This work is expected to open up a promising direction for the practical viability of high-energy Li-S batteries.

Subject Areas: Inorganic Chemistry, Energy Materials, Porous Material

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Metal-organic framework-derived Co9S8 arrays are grown onto 3D graphene foam

-

•

Co9S8-3DGF serves as a free-standing, binder-free host for sulfur cathodes

-

•

Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode exhibits high capacity with long cycle life

-

•

Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode displays a remarkably high areal capacity

Inorganic Chemistry; Energy Materials; Porous Material

Introduction

With the advances in portable electronics and interest in electric vehicles, the demand for high-performance energy storage devices is exponentially growing (Ji et al., 2016, Ji et al., 2017, Cao et al., 2014, He et al., 2016a, He et al., 2016b, He et al., 2016c, He et al., 2017a, He et al., 2017b). Rechargeable lithium-sulfur (Li-S) batteries are appealing as one of the most attractive candidates for energy storage because of their high theoretical energy density and capacity (Manthiram et al., 2014, Manthiram et al., 2015, Wu et al., 2016, He et al., 2017a, He et al., 2017b, Zhou et al., 2015a, Zhou et al., 2015b, Zhong et al., 2018). However, Li-S batteries still face serious drawbacks toward practical applications, including the insulating nature of sulfur and the migration of soluble lithium polysulfides (LiPSs), which give rise to low capacity and rapid capacity decay (Chung and Manthiram, 2018, Kim et al., 2014, He et al., 2016a, He et al., 2016b, He et al., 2016c, Xia et al., 2017). Extensive strategies have been proposed to address these issues. A combination of sulfur and conductive carbonaceous materials, such as reduced graphene oxide, three-dimensional graphene foam (3DGF), carbon nanotube, or conducting polymers, has been considered as an effective approach to improve the electrical conductivity of the electrode and physically confine the soluble LiPSs (He et al., 2015, Chen et al., 2013, Sun et al., 2014). However, due to the weak physical interaction between nonpolar carbonaceous materials and polar LiPSs, the severe capacity degradation still remains during long-term cycling (Zhou et al., 2017, Li et al., 2015, Liu et al., 2017a, Liu et al., 2017b, Xia et al., 2018).

Recently, it has been illustrated that polar materials can significantly improve the chemical adsorption capability for LiPSs, and strenuous efforts have been pursued to develop polar sulfur hosts with strong chemical interaction toward polysulfides species. For example, metal-organic frameworks (MOF) with strong Lewis acid-base interactions for LiPSs are efficient in entrapping polar LiPSs (Zheng et al., 2014, He et al., 2016a, He et al., 2016b, He et al., 2016c) and improving cycling stability when used in the cathodes of Li-S batteries. Polar oxides, such as TiO2, MnO2, SiO2, and V2O5, have also been explored as host materials for Li-S batteries owing to their strong affinity to LiPSs (Zhou et al., 2015a, Zhou et al., 2015b, Kong et al., 2017, Liu et al., 2017a, Liu et al., 2017b). However, these oxides usually have relatively poor electrical conductivity, which tends to slow down the electrode kinetics and thus compromises the utilization of sulfur and the rate capability (Pu et al., 2017). Therefore, metal sulfides (Co9S8, CoS2, and Co3S4) and metal nitride (TiN) with high conductivity and strong chemical interaction for LiPSs have been proposed as hosts for sulfur in Li-S batteries (Pang et al., 2016, Yuan et al., 2016, Chen et al., 2017, Li et al., 2017). However, rational nanoarchitecture designs to improve the utilization of sulfur particularly at higher sulfur loading and content is still challenging, and most of such sulfur composite cathodes still require polymer binders, conductive additives, and metallic current collectors, which not only reduce the power density of the cell but also degrade the long-term cycling.

Herein, we choose a chemical vapor deposition (CVD)-grown 3DGF with high conductivity and excellent flexibility as a binder-free, free-standing skeleton and the conductive hollow polar cobalt sulfide (Co9S8) arrays directly grown on 3DGF skeleton as an efficient sulfur host for Li-S batteries. Benefiting from the well-designed hierarchical Co9S8-3DGF nanoarchitecture, the hollow Co9S8 nanowall arrays anchored onto 3DGF offer abundant nanoporous space to accommodate a large amount of sulfur, allow sufficient electrolyte penetration, and facilitate the transport of ions/electrons. The binder-free, free-standing Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode without polymer binders, conductive additives, and metallic current collectors delivers a remarkably high areal capacity of 10.9 mA hr cm−2 even with a very high sulfur loading (10.4 mg cm−2) and sulfur content (86.9 wt%) and exhibits significant improvement in the specific capacity, rate capability, and long-term cycling stability.

Results

The synthetic strategy of the Co9S8-3DGF/S is schematically shown in Figure 1A; for detailed synthesis procedure, see the Transparent Methods. First, a facile solution method was used to grow cobalt-based MOF solid nanowall arrays onto a piece of 3DGF. Then, through a subsequent solvothermal reaction with thioacetamide (TAA) in ethanol, the Co-MOF solid nanowall arrays were transformed to hollow Co9S8 arrays. The color of Co-MOF/3DGF changed from purple to black after the transformation to Co9S8-3DGF (Figure S1). After this sulfurization treatment, the obtained Co9S8-3DGF was mixed with an appropriate amount of sulfur, and the sulfur was impregnated into the Co9S8-3DGF by a modified melt-diffusion strategy. Benefiting from the efficient surface bonding between the Co9S8 nanowall arrays and the sulfur species, the dissolution and migration of LiPSs were effectively alleviated during the charge/discharge process (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of the Co9S8-3DGF/S Composite

(A) Schematic of the synthetic procedure of the Co9S8-3DGF/S composite.

(B) Advantages of the Co9S8-3DGF/S composite over 3DGF/S.

Through a facile solution method, the solid Co-MOF nanowall arrays are uniformly grown onto the 3DGF. The scanning electron microscopic (SEM) images in Figures 2A–2C show that the skeleton of 3DGF is homogenously coated by a solid Co-MOF with nanowall morphology. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the Co-MOF in Figure S2 are in agreement with previous reports (Guan et al., 2017). Figure 2D illustrates that the typical array morphology and a uniform coating on 3DGF are maintained after sulfurization treatment with TAA. As shown in Figures 2E, 2F, and S3, a hollow structure is formed in Co9S8-3DGF, which can be attributed to the Kirkendall effect (Liu et al., 2016). Specific surface area results further confirm the high specific area of Co9S8-3DGF (Figure S4). The absence of the Co-MOF peaks in the XRD pattern of Co9S8-3DGF (Figure S5A) confirms the successful transformation from Co-MOF to Co9S8. After the sulfur impregnation into Co9S8-3DGF, the architecture of Co9S8-3DGF/S still remains as nanowall arrays, as shown in Figure 2G. It is worth noticing that those nanowall arrays are solid, indicating that the sulfur has been effectively confined into the hollow Co9S8 nanowall arrays (Figures 2H and 2I). Such a unique architecture with an excellent interfacial contact between sulfur-Co9S8 and 3DGF can help realize the fast diffusion of LiPSs on the Co9S8 surface to the highly conductive graphene surface. As a result, strong entrapment (by Co9S8) and fast electron transfer (by 3DGF) for LiPS conversion can be simultaneously realized, avoiding the accumulation of LiPSs and improving their utilization. The XRD pattern of Co9S8-3DGF/S (Figure S5A) also suggests the successful introduction of sulfur. The SEM images and the corresponding elemental mappings in Figures S6A–S6F evidently indicate a uniform distribution of Co9S8 and S in Co9S8-3DGF/S. The TGA curves (Figure S5B) show that the content of sulfur in Co9S8-3DGF/S is 79.2 wt.% (6.2 mg cm−2). For comparison, 3DGF/S was also prepared. Owing to the hydrophobic nature of the 3DGF, the hosted sulfur on 3DGF tends to severely aggregate into bulk particles (Figure S7).

Figure 2.

Morphology and Microstructure Analysis of the Co9S8-3DGF/S Cathode

Various magnification SEM inspections of (A–C) Co-MOF-3DGF, (D–F) Co9S8-3DGF, and (G–I) Co9S8-3DGF/S.

Discussion

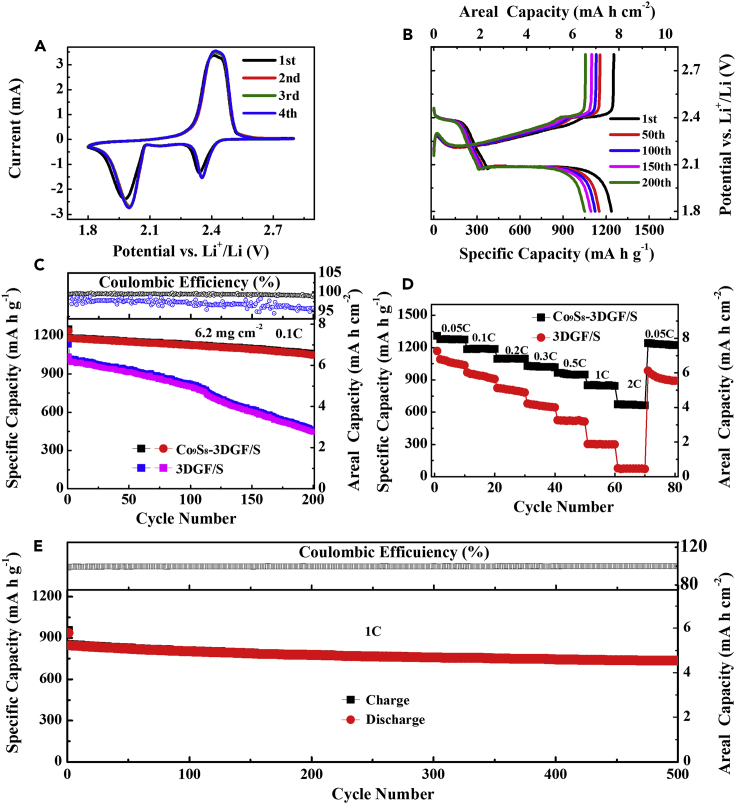

To demonstrate that such a rational architecture of Co9S8-3DGF is beneficial for the electrochemical properties of Li-S batteries, the Co9S8-3DGF/S was cut and directly used as a binder-free, free-standing cathode. As shown in Figure 3A, the cyclic voltammetry (CV) profiles in the first four cycles of the cell with Co9S8-3DGF/S are obtained with a sulfur loading of 6.2 mg cm−2 at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1 in the voltage range of 1.8–2.8 V. Compared with our previous reports, Co9S8-3DGF/S shows a similar electrochemical reaction (Qie and Manthiram, 2016, Su and Manthiram, 2012, Xu and Manthiram, 2017, Xu et al., 2016). The two main reduction peaks at 2.34 and 1.97 V in the initial cathodic sweep reflect the transformation of S to long-chain LiPSs and ultimately to Li2S. The oxidation peak located at 2.41 V corresponds to the conversion of Li2S to LiPSs and finally to sulfur. The overlapped CV profiles after the initial cycles evidence the highly reversible electrochemical process. As shown in Figure S8, the rate-dependent CV curves of Co9S8-3DGF/S were obtained and the corresponding Li-ion diffusion coefficient (DLi+) was calculated. The DLi+ values of C1, C2, and A peaks are, respectively, 1.72 ×10−8, 4.85 × 10−8, and 2.91 × 10−8 cm2 s−1. These DLi+ values are close to the values in our previous report (Chung et al., 2016). Importantly, the polarization of the Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode with a high sulfur loading (6.2 mg cm−2) and high sulfur content (79.6 wt.%) remains low during the electrochemical process. Considering the above structural analyses on Co9S8-3DGF/S, such low polarization is due to the unique architecture of Co9S8-3DGF/S offering excellent trapping-diffusion conversion process. Such results were further confirmed by the impedance values of Co9S8-3DGF/S relative to those of 3DGF/S (Figure S9). The charge/discharge curves of the cell with Co9S8-3DGF/S at C/10 rate (1C = 1,675 mA g−1) well coincide with its CV behavior. (Figure 3B) Remarkably, the potential plateaus remain the same even after 200 cycles, implying an excellent immobilization of Co9S8-3DGF/S for sulfur species.

Figure 3.

Electrochemical Performance of the Co9S8-3DGF/S Cathode

(A) CV curves of the Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode at 0.1 mV s−1 at 1.8–2.8 V.

(B) Charge/discharge profiles of the Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode.

(C) Cycling stability of the Co9S8-3DGF/S and 3DGF/S cathodes at C/10 rate for 200 cycles.

(D) Rate performances at various cycling rates of the Co9S8-3DGF/S and 3DGF/S electrodes.

(E) Cycling performances of the Co9S8-3DGF/S electrodes for long-term cycling at 1C rate.

The cyclic performances at C/10 rate in the voltage range of 1.8–2.8 V for the Co9S8-3DGF/S and 3DGF/S cathodes were measured with the same sulfur loading of 6.2 mg cm−2. Co9S8-3DGF/S exhibits pronounced cycling stability with a high capacity retention of 84.9% after 200 cycles, as shown in Figure 3C. Importantly, even after 200 cycles, Co9S8-3DGF/S still can maintain its nanowall array morphology (Figure S10). By sharp contrast, the 3DGF/S cathode shows a rapid capacity degradation after 200 cycles with a poor capacity retention of 42.8%. The fast capacity decay of 3DGF/S is attributed to the weak affinity of 3DGF to sulfur species and poor physical entrapment. To better understand the synergistic effect of each component and to optimize the electrochemical performances, the electrochemical performance of Co9S8-3DGF/S with a Co9S8 loading of 2.3 mg cm−2 was obtained. As shown in Figure S11, although a higher content of Co9S8 can improve the adsorption toward LiPSs, it will decrease the conductivity of the electrode. As a result, the utilization of active materials decreases and the specific capacity of the cathode is low. The visual observations of Co9S8-3DGF/S and 3DGF/S confirm that polysulfide dissolution is effectively mitigated in Co9S8-3DGF/S during the charge/discharge process (Figure S12).

The rate capabilities of the cells with Co9S8-3DGF/S at various rates from C/20 to 2C are shown in Figures 3D and S13. At a C/20 rate, the cell with Co9S8-3DGF/S delivers a high specific capacity of 1,306 mA hr g−1. Even at a high rate of 2C, the capacity of the cell with Co9S8-3DGF/S still remains stable at 670 mA hr g−1, which is significantly better than that of the cell with 3DGF/S (74.9 mA hr g−1) under the same conditions. Furthermore, when the C-rate is switched back to C/20, the capacity of the cell with Co9S8-3DGF/S recovers to the original value, indicating the excellent mechanical stability within the cathode. It is known that the long-term charge/discharge process is still a challenge for high-sulfur-loading cathodes. To further illustrate the structural advantages of Co9S8-3DGF/S, the prolonged cycling performance was evaluated at 1C rate for 500 cycles. As shown in Figure 3E, the Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode exhibits an extraordinary cyclic stability with a high capacity retention of 77.2%. Even at a high rate of 1C after 500 cycles, the Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode still delivers 736 mA hr g−1.

The areal capacity of the Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode was also assessed. As shown in Figure 4, the Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode with a sulfur loading of 6.2 mg cm−2 delivers at C/10 rate a high areal capacity of 7.6 mA hr cm−2, which is much higher than that of commercial lithium-ion batteries (typically 4 mA hr cm−2) (Hu et al., 2016). Furthermore, an even higher areal capacity of 10.9 mA hr cm−2 could be realized at a rate of C/10 by increasing the sulfur loading to 10.4 mg cm−2 (86.9 wt.%). It is obvious that the areal capacity of our Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode is much higher compared with those of recently reported high-areal-capacity Li-S cathodes with higher sulfur loading (Table S1). This value is nearly three times more than that of commercial Li-ion batteries, indicating the promise of Co9S8-3DGF/S cathodes. In addition, even with such a high sulfur loading of 10.4 mg cm−2, the Co9S8-3DGF/S cathode still exhibits good cycling stability for 200 cycles. Such impressive features imply that the Co9S8-3DGF/S is an attractive cathode for the practical Li-S batteries.

Figure 4.

The Electrochemical Performance of Co9S8-3DGF/S Cathode with High Sulfur Loading

(A) Cycling performances of the Co9S8-3DGF/S electrodes with 6.2, 8.1, and 10.4 mg cm−2 sulfur loadings and (B) the corresponding areal capacities.

The SEM images of the lithium foils and the photographs of the separators recovered from the cells with the Co9S8-3DGF/S and 3DGF/S cathodes after 200 cycles were further analyzed to elucidate the excellent confinement of the sulfur species within Co9S8-3DGF/S (Figures S14 and S15). Severe corrosion observed on the surface of lithium foil with the 3DGF/S cathode indicates that the 3DGF can only provide weak protection for lithium foil from LiPSs. The obvious color changes of the separator in the cell with 3DGF/S further imply the existence of severe shuttle effects. In addition, the photographs of the absorption experiments of 3DGF and Co9S8-3DGF visually demonstrate that Co9S8 can provide strong interaction for LiPSs (Figure 5). Correspondingly, a dramatic decrease can also be detected in the ultraviolet (UV)-visible absorption spectra. The peak intensity of the S62− species is much lower for Co9S8-3DGF than for 3DGF, implying that Co9S8-3DGF has better affinity and strong adsorption. Moreover, to further quantitatively evaluate the chemical adsorption of Co9S8 for LiPSs, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was carried out. After contacting with Li2S6 for 1 hr, the peaks of Co 2p3/2 shifts toward higher binding energies and the satellite peaks become obvious, implying electron transfer from Li2S6 molecules to Co, as shown in Figure S16 (Pu et al., 2017). Such an analysis directly indicates a strong chemical interaction between Co9S8 and Li2S6 and evidently provides insights on the electrochemical improvement offered by Co9S8-3DGF/S.

Figure 5.

Adsorption of Co9S8-3DGF toward Lithium Polysulfides

UV-visible spectra of the Li2S6 solution with 3DGF and Co9S8-3DGF. Inset: the photograph of the sealed vials of a Li2S6 solution with a solvent of 1,3-dioxolane (DOL) and 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME) after contacting with 3DGF and Co9S8-3DGF for 1 hr.

In summary, the rational design and fabrication of MOF-derived cobalt sulfide arrays anchored onto 3DGF (Co9S8-3DGF) has been presented as an efficient sulfur host for long-life, highly efficient Li-S batteries. The Co9S8-3DGF/S can be directly used as a binder-free, free-standing cathode. Moreover, the Co9S8-3DGF/S exhibits pronounced electrochemical performance owing to its unique 3D hierarchical nanoarchitecture, which can synergistically realize a strong chemical entrapment of LiPSs (by Co9S8) and fast transport of electrons (by 3DGF), avoid the accumulation of LiPSs, and improve the utilization of sulfur. As a result, Co9S8-3DGF/S with a very high sulfur loading of 10.4 mg cm−2 delivers excellent electrochemical performance. This work provides new insights into the rational design of binder-free, free-standing cathodes for highly efficient Li-S batteries.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Science and Engineering, under award number DE-SC000597. One of the authors (J.H.) thanks the China Scholarship Council (Grant No. 201606070032) for the award of a fellowship.

Author Contributions

J.H. designed and carried out the experimental work, J.H., Y.C., and A.M. contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: June 29, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Transparent Methods, 16 figures, and 1 table and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2018.05.005.

Contributor Information

Yuanfu Chen, Email: yfchen@uestc.edu.cn.

Arumugam Manthiram, Email: manth@austin.utexas.edu.

Supplemental Information

References

- Cao X., Zheng B., Rui X., Shi W., Yan Q., Zhang H. Metal oxide-coated three-dimensional graphene prepared by the use of metal–organic frameworks as precursors. Angew. Chem. 2014;126:1428–1433. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Zhao T., Lu J., Wu F., Li L., Chen J., Tan G., Ye Y., Amine K. Graphene-based three-dimensional hierarchical sandwich-type architecture for high-performance Li/S batteries. Nano Lett. 2013;13:4642–4649. doi: 10.1021/nl4016683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Zhang Z., Cheng B., Chen R., Hu Y., Ma L., Zhu G., Liu J., Jin Z. Self-templated formation of interlaced carbon nanotubes threaded hollow Co3S4 nanoboxes for high-rate and heat-resistant lithium–sulfur batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:12710–12715. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b06973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S., Manthiram A. Designing lithium-sulfur cells with practically necessary parameters. Joule. 2018;2:710–724. [Google Scholar]

- Chung S., Chang C., Manthiram A. A carbon-cotton cathode with ultrahigh-loading capability for statically and dynamically stable lithium–sulfur batteries. ACS Nano. 2016;10:10462–10470. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b06369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan C., Liu X., Elshahawy A.M., Zhang H., Wu H., Pennycook S.J., Wang J. Metal–organic framework derived hollow CoS2 nanotube arrays: an efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Nanoscale Horiz. 2017;2:342–348. doi: 10.1039/c7nh00079k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Chen Y., Li P., Fu F., Wang Z., Zhang W. Three-dimensional cnt/graphene–sulfur hybrid sponges with high sulfur loading as superior-capacity cathodes for lithium–sulfur batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015;3:18605–18610. [Google Scholar]

- He J., Chen Y., Lv W., Wen K., Li P., Qi F., Wang Z., Zhang W., Li Y., Qin W., He W. Highly-flexible 3d Li2S/graphene cathode for high-performance lithium sulfur batteries. J. Power Sources. 2016;327:474–480. [Google Scholar]

- He J., Chen Y., Lv W., Wen K., Wang Z., Zhang W., Li Y., Qin W., He W. Three-dimensional hierarchical reduced graphene oxide/tellurium nanowires: a high-performance freestanding cathode for Li–Te batteries. ACS Nano. 2016;10:8837–8842. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b04622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Chen Y., Lv W., Wen K., Xu C., Zhang W., Li Y., Qin W., He W. From metal–organic framework to Li2S@C–Co–N nanoporous architecture: a high-capacity cathode for lithium–sulfur batteries. ACS Nano. 2016;10:10981–10987. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b05696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Luo L., Chen Y., Manthiram A. Yolk-shelled C@Fe3O4 nanoboxes as efficient sulfur hosts for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 2017 doi: 10.1002/adma.201702707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Lv W., Chen Y., Wen K., Xu C., Zhang W., Li Y., Qin W., He W. Tellurium-impregnated porous cobalt-doped carbon polyhedra as superior cathodes for lithium–tellurium batteries. ACS Nano. 2017;11:8144–8152. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b03057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G., Xu C., Sun Z., Wang S., Cheng H., Li F., Ren W. 3d graphene-foam-reduced-graphene-oxide hybrid nested hierarchical networks for high-performance Li-S batteries. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:1603–1609. doi: 10.1002/adma.201504765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji D., Zhou H., Tong Y., Wang J., Zhu M., Chen T., Yuan A. Facile fabrication of MOF-derived octahedral CuO wrapped 3d graphene network as binder-free anode for high performance lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;313:1623–1632. [Google Scholar]

- Ji D., Zhou H., Zhang J., Dan Y., Yang H., Yuan A. Facile synthesis of a metal–organic framework-derived Mn2O3 nanowire coated three-dimensional graphene network for high-performance free-standing supercapacitor electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4:8283–8290. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Hwang T.H., Kim B.G., Min J., Choi J.W. A lithium-sulfur battery with a high areal energy density. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014;24:5359–5367. [Google Scholar]

- Kong W., Yan L., Luo Y., Wang D., Jiang K., Li Q., Fan S., Wang J. Ultrathin MnO2/graphene oxide/carbon nanotube interlayer as efficient polysulfide-trapping shield for high-performance li-s batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017;27:1606663. [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Guan B.Y., Zhang J., Lou X.W.D. A compact nanoconfined sulfur cathode for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Joule. 2017;1:576–587. [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Zhang J., Lou X.W.D. Hollow carbon nanofibers filled with MnO2 nanosheets as efficient sulfur hosts for lithium-sulfur batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;127:13078–13082. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Wu C., Xiao D., Kopold P., Gu L., van Aken P.A., Maier J., Yu Y. MOF-derived hollow Co9S8 nanoparticles embedded in graphitic carbon nanocages with superior li-ion storage. Small. 2016;17:201503821. doi: 10.1002/smll.201503821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Li Q., Qin X., Liang G., Han W., Zhou D., He Y., Li B., Kang F. Suppressing self-discharge and shuttle effect of lithium-sulfur batteries with V2O5-decorated carbon nanofiber interlayer. Small. 2017;13:1602539. doi: 10.1002/smll.201602539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Huang J., Zhang Q., Mai L. Nanostructured metal oxides and sulfides for lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1601759. doi: 10.1002/adma.201601759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthiram A., Chung S., Zu C. Lithium-sulfur batteries: progress and prospects. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:1980–2006. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthiram A., Fu Y., Chung S., Zu C., Su Y. Rechargeable lithium–sulfur batteries. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:11751–11787. doi: 10.1021/cr500062v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Q., Kundu D., Nazar L.F. A graphene-like metallic cathode host for long-life and high-loading lithium–sulfur batteries. Mater. Horiz. 2016;3:130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Pu J., Shen Z., Zheng J., Wu W., Zhu C., Zhou Q., Zhang H., Pan F. Multifunctional Co3S4 @sulfur nanotubes for enhanced lithium-sulfur battery performance. Nano Energy. 2017;37:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Qie L., Manthiram A. High-energy-density lithium–sulfur batteries based on blade-cast pure sulfur electrodes. ACS Energy Lett. 2016;1:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Su Y., Manthiram A. Lithium–sulphur batteries with a microporous carbon paper as a bifunctional interlayer. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:1166. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Li M., Jiang Y., Kong W., Jiang K., Wang J., Fan S. Sulfur nanocrystals confined in carbon nanotube network as a binder-free electrode for high-performance lithium sulfur batteries. Nano Lett. 2014;14:4044–4049. doi: 10.1021/nl501486n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhao E., Gordon D., Xiao Y., Hu C., Yushin G. Infiltrated porous polymer sheets as free-standing flexible lithium-sulfur battery electrodes. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:6365–6371. doi: 10.1002/adma.201600757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Fang R., Xiao Z., Huang H., Gan Y., Yan R., Lu X., Liang C., Zhang J., Tao X., Zhang W. Confining sulfur in n-doped porous carbon microspheres derived from microalgaes for advanced lithium–sulfur batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:23782–23791. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b05798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Zhong H., Fang R., Liang C., Xiao Z., Huang H., Gan Y., Zhang J., Tao X., Zhang W. Biomass derived Ni(OH)2@porous carbon/sulfur composites synthesized by a novel sulfur impregnation strategy based on supercritical co2 technology for advanced li-s batteries. J. Power Sources. 2018;378:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Manthiram A. Hollow cobalt sulfide polyhedra-enabled long-life, high areal-capacity lithium-sulfur batteries. Nano Energy. 2017;33:124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Qie L., Manthiram A. An integrally-designed, flexible polysulfide host for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries with stabilized lithium-metal anode. Nano Energy. 2016;26:224–232. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z., Peng H., Hou T., Huang J., Chen C., Wang D., Cheng X., Wei F., Zhang Q. Powering lithium–sulfur battery performance by propelling polysulfide redox at sulfiphilic hosts. Nano Lett. 2016;16:519–527. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Tian J., Wu D., Gu M., Xu W., Wang C., Gao F., Engelhard M.H., Zhang J., Liu J., Xiao J. Lewis acid–base interactions between polysulfides and metal organic framework in lithium sulfur batteries. Nano Lett. 2014;14:2345–2352. doi: 10.1021/nl404721h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y., Xia X., Deng S., Zhan J., Fang R., Xia Y., Wang X., Zhang Q., Tu J. Popcorn inspired porous macrocellular carbon: rapid puffing fabrication from rice and its applications in lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018;8:1701110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G., Li L., Wang D., Shan X., Pei S., Li F., Cheng H. A flexible sulfur-graphene-polypropylene separator integrated electrode for advanced li-s batteries. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:641–647. doi: 10.1002/adma.201404210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G., Zhao Y., Zu C., Manthiram A. Free-standing TiO2 nanowire-embedded graphene hybrid membrane for advanced Li/dissolved polysulfide batteries. Nano Energy. 2015;12:240–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G., Tian H., Jin Y., Tao X., Liu B., Zhang R., Seh Z.W., Zhuo D., Liu Y., Sun J. Catalytic oxidation of Li2S on the surface of metal sulfides for Li−S batteries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:840–845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615837114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.