Retroviruses have adapted to living in concert with their hosts throughout vertebrate evolution. Over the years, the study of these relationships revealed the presence of host proteins called restriction factors that inhibit retroviral replication in host cells. The first of these restriction factors to be identified, encoded by the Fv1 gene found in mice, was thought to have originated in the genus Mus. In this study, we utilized genome database searches and DNA sequencing to identify Fv1 copies in multiple rodent lineages. Our findings suggest a minimum time of insertion into the genome of rodents of 45 million years for the ancestral progenitor of Fv1. While Fv1 is not detectable in some lineages, we also identified full-length orthologs showing signatures of a molecular “arms race” in a family of rodent species indigenous to Africa. This finding suggests that Fv1 in these species has been coevolving with unidentified retroviruses for millions of years.

KEYWORDS: Fv1 restriction factor, gammaretrovirus restriction, mouse leukemia viruses, rodent evolution

ABSTRACT

The laboratory mouse Fv1 gene encodes a retroviral restriction factor that mediates resistance to murine leukemia viruses (MLVs). Sequence similarity between Fv1 and the gag protein of the murine endogenous retrovirus L (MuERV-L) family of ERVs suggests that Fv1 was coopted from an ancient provirus. Previous evolutionary studies found Fv1 orthologs only in the genus Mus. Here, we describe identification of orthologous Fv1 sequences in several species belonging to multiple families of rodents outside the genus Mus. We show that these Fv1 orthologs are in the same region of conserved synteny, between the genes Miip and Mfn2, suggesting a minimum insertion time of 45 million years for the ancient progenitor of Fv1. Our analysis also revealed that Fv1 was not detectable or heavily mutated in some lineages in the superfamily Muroidea, while, in concert with previous findings in the genus Mus, we found strong evidence of positive selection of Fv1 in the African clade in the subfamily Muridae. Residues identified as evolving under positive selection include those that have been previously found to be important for restriction of multiple retroviral lineages. Taken together, these findings suggest that the evolutionary origin of Fv1 substantially predates Mus evolution, that the rodent Fv1 has been shaped by lineage-specific differential selection pressures, and that Fv1 has long been evolving under positive selection in the rodent family Muridae, supporting a defensive role that significantly antedates exposure to MLVs.

IMPORTANCE Retroviruses have adapted to living in concert with their hosts throughout vertebrate evolution. Over the years, the study of these relationships revealed the presence of host proteins called restriction factors that inhibit retroviral replication in host cells. The first of these restriction factors to be identified, encoded by the Fv1 gene found in mice, was thought to have originated in the genus Mus. In this study, we utilized genome database searches and DNA sequencing to identify Fv1 copies in multiple rodent lineages. Our findings suggest a minimum time of insertion into the genome of rodents of 45 million years for the ancestral progenitor of Fv1. While Fv1 is not detectable in some lineages, we also identified full-length orthologs showing signatures of a molecular “arms race” in a family of rodent species indigenous to Africa. This finding suggests that Fv1 in these species has been coevolving with unidentified retroviruses for millions of years.

INTRODUCTION

As obligate intracellular parasites, retroviruses have been coevolving with their hosts for more than 450 million years (1). While successful infection of a cell by a retrovirus requires cooption of cellular proteins, host cells have also evolved innate immune restriction factors to block viral infection (2). The first host restriction factor to be identified, Fv1, was discovered when it was observed that certain isolates of murine leukemia virus (MLV) were unable to replicate in some strains of laboratory mice (3). Several decades later, the gene responsible for this restriction, Fv1, was identified by positional cloning (4) and shown to be related to the gag gene of a group of endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) in mice called MuERV-L (murine endogenous retrovirus L) (4, 5). This finding, however, did not lead to other studies designed to describe the origin of Fv1 or its likely retroviral progenitor.

In laboratory and wild mice, 3 major variants of Fv1 have been identified (6). The Fv1n and Fv1b variants were originally discovered in NIH Swiss and BALB/c mice and are permissive to infection by N- and B-tropic MLVs, respectively (7). The Fv1nr variant was later found in inbred laboratory mice, as well as some wild mouse species, and is permissive to infection only by the NR-tropic subset of N-tropic MLVs (8). In addition to these variants, the null Fv1− allele was found in some wild mice that were later shown to be lacking a functional open reading frame (ORF) of Fv1 (9), and another restrictive allele, Fv1d, was found in DBA strain mice (10, 11). MLVs that are not restricted by any of these alleles are termed NB tropic (7).

Functional studies of Fv1 alleles and different MLV strains led to the identification of amino acid residue 110 in the viral gag capsid gene as the main determinant of N- and B-tropism (11). Several other residues in the MLV capsid were subsequently identified as important for NB- and NR-tropism (8, 12). These findings indicate that Fv1 targets the capsid protein of MLV for restriction. On the host side of this antagonistic relationship, the three major Fv1 variants in laboratory mice differ at only 3 amino acid residues (352, 358, and 399) and in the size and sequence of the N-terminal tail (4, 13, 14). Despite these findings, the exact mechanism of Fv1 restriction is still a mystery, although it has been shown that Fv1 acts to block virus replication after reverse transcription and before integration (15).

Fv1 is absent from the genome of the rat (4, 9), and a previous report suggested that it could not be amplified from Apodemus sylvaticus, suggesting it was acquired more recently in rodents (16). In the genus Mus, which includes laboratory mice, Fv1 is missing from species at the base of the phylogenetic tree, suggesting it originated in the genus between 4 and 7 million years ago (mya) (16, 17). We have previously shown that Fv1 has evolved under positive selection in the genus Mus, suggesting an evolutionary “arms race” between Fv1 and retroviruses that are antagonized by Fv1 (17). However, since infection with MLVs dates only to the divergence of Mus musculus subspecies (0.5 to 1.0 mya), the evidence of an older arms race suggested that Fv1 antagonizes other retroviruses (17). This was confirmed by the demonstration that Fv1 has antiviral activity against foamy viruses and equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV), a lentivirus (16).

Because Fv1 has broad antiretroviral activity that is not restricted to MLVs, it is possible that this restriction factor, derived from an ERV family whose acquisition significantly predates Mus, MuERV-L, may have unidentified orthologs in other rodent species. In this study, we report identification of Fv1 orthologs in several species belonging to multiple families of the suborder Myomorpha outside the genus Mus. Our analysis also shows that these Fv1 orthologs are in the same region of conserved synteny as the Fv1 ortholog found in M. musculus. In addition, we demonstrate that Fv1 displays signatures of positive selection in an African clade of the subfamily Muridae. Taken together, these data suggest a minimum insertion time for the progenitor of Fv1 into the genome of Muroidea of approximately 45 million years (18–22) and further substantiates the earlier conclusion that that Fv1 must have had antiviral activity well before the appearance of MLVs.

RESULTS

Identification of Fv1 in murids outside the genus Mus.

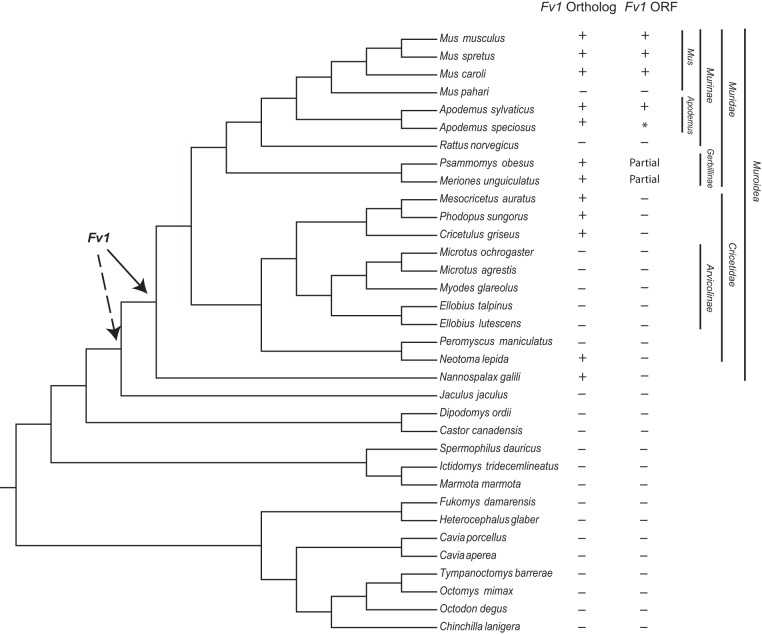

During an in silico search for MuERV-L elements that resemble Fv1 in the genomes of rodents, we identified several hits with high identity to Fv1 in multiple species outside the genus Mus. This prompted us to conduct an extended search for Fv1-like elements in the genomes of rodents with published and assembled genomes. Using the Fv1 ORF sequence from the mouse reference assembly (NM_010244) as the probe, we searched the individual genomes of each rodent species with assembled genomes in the GenBank database (Table 1). This analysis revealed Fv1-like sequences in several species outside the genus Mus, including two species of the genus Apodemus, two species that belong to the subfamily Gerbillinae, several species in the family Cricetidae, and Nannospalax galili, a species in the family Spalacidae (Fig. 1). This in silico search also revealed that the Fv1 sequence was not detectable in several species (Fig. 1). It has been previously shown that Fv1 is absent in Mus pahari and Rattus norvegicus (4, 9, 17). Our present analysis failed to identify Fv1 in five species that belong to the subfamily Arvicolinae, indicating possible loss in a common ancestor, as well as in another species in the family Cricetidae; Peromyscus maniculatus (Fig. 1). Moreover, none of the Fv1 orthologs identified in the species outside the genera Apodemus and Mus contained a full-length intact ORF (Fig. 1; see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). The Fv1 genes found in species outside the family Muridae contain insertions and deletions that all introduce premature stop codons (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 1.

Genome assemblies analyzed for Fv1 orthologs

| Species | Assembly GenBank ID no. | Fv1 sequence location | Assembly level/scaffold or contig N50c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mus musculus | 5015798 | Chromosome 4; 147868979–147870358 | Chromosome/52,589,046 |

| Mus spretus | 3209118 | Chromosome 4; 143977914–143979293 | Chromosome/131,945,496 |

| Mus carolia | 4428938 | Chromosome 4; 137705488–137706894 | Chromosome/122,627,250 |

| Chromosome 6; 29191993–29193375 | |||

| Mus pahari | 4428958 | No Fv1 | Chromosome/111,406,228 |

| Apodemus sylvaticus | 2366688 | Scaffold 32866; 29576–30952 | Scaffold/245,982 |

| Apodemus speciosusb | 5057288 | Scaffold 251367; 149–1069 | Scaffold/49,031 |

| Scaffold 156636; 1512–1851 | |||

| Rattus norvegicus | 1156538 | No Fv1 | Chromosome/14,986,627 |

| Psammomys obesus | 4676748 | Contig 23267; 10866–12468 | Contig/76,398 |

| Meriones unguiculatus | 4620268 | Scaffold 711; 275895–277120 | Scaffold/374,687 |

| Mesocricetus auratus | 562298 | Scaffold 00091; 8678386–8679260 | Scaffold/12,753,307 |

| Phodopus sungorus | 3400648 | Contig MCBN011381412; 114–977 | Contig/2,392 |

| Cricetulus griseus | 301008 | Scaffold 5243; 56464–56406 | Scaffold/1,147,233 |

| Microtus ochrogaster | 504458 | No Fv1 | Chromosome/17,270,019 |

| Microtus agrestis | 2366748 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/896,668 |

| Myodes glareolus | 2366508 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/364,535 |

| Ellobius talpinus | 3342798 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/15,246 |

| Ellobius lutescens | 3342778 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/242,123 |

| Peromyscus maniculatus | 869028 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/3,760,915 |

| Neotoma lepida | 3322358 | Scaffold 7; 325138–326237 | Scaffold/119,373 |

| Nannospalax galili | 1095108 | Scaffold 1225; 281074–282189 | Scaffold/3,618,479 |

| Jaculus jaculus | 406368 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/22,080,993 |

| Dipodomys ordii | 1420568 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/11,931,245 |

| Castor canadensis | 4088328 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/317,708 |

| Spermophilus dauricus | 5170358 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/1.761.345 |

| Ictidomys tridecemlineatus | 317808 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/8,192,786 |

| Marmota marmota | 2704858 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/31,640,621 |

| Fukomys damarensis | 1195548 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/5,314,287 |

| Heterocephalus glaber | 362148 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/20,532,749 |

| Cavia porcellus | 175118 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/27,942,054 |

| Cavia aperea | 1067048 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/24,928,671 |

| Tympanoctomys barrerae | 5381778 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/4,698 |

| Octomys mimax | 5381798 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/4,874 |

| Octodon degus | 375158 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/12,091,372 |

| Chinchilla lanigera | 397218 | No Fv1 | Scaffold/21,893,125 |

| Homo sapiens | 5800238 | No Fv1 | Chromosome/59,364,414 |

| Oryctolagus cuniculus | 182491 | No Fv1 | Chromosome/35,972,871 |

Two Fv1 copies were found in the Mus caroli genome, on different chromosomes.

A single Fv1 ortholog is split between two scaffolds with overlapping sequences in Apodemus speciosus.

Scaffold N50, length such that scaffolds of this length or longer include half the bases of the assembly; contig N50, length such that sequence contigs of this length or longer include half the bases of the assembly.

FIG 1.

An Fv1 ortholog is present in several rodent families. Shown is a cladogram illustrating the evolutionary relationship between rodent species with a genome assembly in the NCBI database. The species tree was generated with TimeTree (20). Genus, family, subfamily, and superfamily classifications for a subset of species are indicated on the right. + indicates the presence of an Fv1 ortholog or an Fv1 ORF as identified via BLAST searches of each genome assembly. The suggested positions of the Fv1 insertions into the rodent genomes are indicated by arrows. The solid arrow indicates the location of the minimum insertion time suggested by the database analysis, while the dashed arrow indicates the possible Fv1 insertion at the base of the suborder Myomorpha. *, the Fv1 ORF of Apodemus speciosus is split between two overlapping scaffolds. Merinones unguiculatus and Psammomys obesus contained only a partial ORF with premature stop codons.

This initial search for Fv1 outside the genus Mus relied on previously assembled genome data. However, Fv1 shares homology with repetitive elements in the MuERV-L class of ERVs (5, 23), and despite the improvements in whole-genome sequencing and assembly made in recent years, sequencing mistakes involving such repeat sequences are still common (24). To confirm our findings from the database search, we sequenced Fv1 orthologs and the immediate surrounding regions from three species outside the genus Mus; Cricetulus griseus (Chinese hamster), Mesocricetus auratus (golden hamster), and Meriones unguiculatus (Mongolian gerbil). These species show different levels of genome assembly completeness (Table 1). Our results revealed only minor differences between the sequences in the database assemblies and the sequences obtained via PCR and Sanger sequencing for all three species (see Data Set S2 in the supplemental material). These results confirm the accuracy of these particular assemblies in the region surrounding the Fv1 ortholog.

Fv1 genes of the superfamily Muroidea map to regions of conserved synteny.

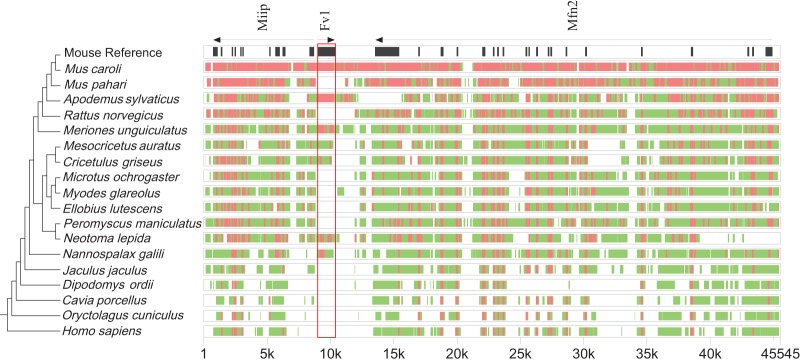

In the mouse genome, Fv1 is located between the genes Miip and Mfn2. Since these genes are present in all the annotated genomes of rodents and primates in the NCBI database, we can use them as a guide to establish that the recovered Fv1-like sequences are orthologs that map to regions of conserved synteny. To this end, we extracted and aligned genomic sequences from 19 species, including mouse, rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), and human (Homo sapiens), as references, using the alignment program MultiPipMaker (25). As shown in Fig. 2, all Fv1 orthologs that were identified via Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) search map between Miip and Mfn2. In addition, alignment of the region between Fv1 and Miip revealed an approximately 1.9-kb deletion that was identified only in the genus Mus (data not shown). The presence of an Fv1 ortholog in this genomic region in Nannospalax galili and its absence from all of the more distantly related species in the order Rodentia suggest a minimum insertion time for the presumed retroviral ancestor of Fv1 into the genome of the common ancestor of Muroidea that is between 42 and 49 million years (18–20, 26, 27). However, since we have access to the genome of only one species, Jaculus jaculus, outside the superfamily Muroidae, in the suborder Myomorpha, we cannot be certain whether this species completely lost Fv1 from its genome, as have some other species in Muroidea, or if it never inherited Fv1 from the common ancestor of all dipodids. Hence, the insertion time point of the retroviral ancestor of Fv1 could be at the base of the suborder Myomorpha, moving the estimated insertion to between 50 and 59 mya (18–20, 26, 27).

FIG 2.

Conserved synteny of Fv1. Genomic segments containing Fv1, Miip, and Mfn2 were extracted from the NCBI genome database for each indicated species. Cross-species homologies were analyzed using the MultiPipMaker alignment tool (25). Exons of Miip, Mfn2, and Fv1 are shown as black boxes in the mouse reference assembly. The Fv1 sequence is boxed in red. Regions with more than 50% but less than 75% identity are shown as green boxes. Regions with more than 75% identity are shown as red boxes. A cladogram representing the phylogenetic relationships between the species is shown on the left. The species tree was generated with TimeTree (20).

Fv1 coding potential in African murids.

Our in silico and subsequent PCR/sequencing analyses indicated that the full-length Fv1 ORF was limited to species belonging to the subfamily Murinae. However, this analysis included only the genera Mus and Apodemus in the subfamily Murinae, as well as only two species in the subfamily Gerbillinae (Fig. 1). To get a better picture of Fv1 ORF retention in the family Muridae, we sequenced Fv1 from the genomic DNA of several members of the family Muridae that are indigenous to sub-Saharan Africa (28). Of the 9 species surveyed, all but one contained a full-length Fv1 ORF (see Data Set S3 in the supplemental material). This result also revealed the presence of a full-length Fv1 ORF in two species outside the subfamily Murinae: Lophuromys sikapusi and Lophuromys flavopunctatus.

One species originally identified as Mylomys dybowskii had a premature stop codon and clustered with species outside its expected subfamily, Murinae, in maximum-likelihood trees, suggesting a misidentification in its species designation (Fig. 3A; see Data Set S3 in the supplemental material). To resolve this discrepancy and to confirm the identities of the other tested species, we sequenced part of exon 1 of Rbp3 (encoding retinol binding protein 3), a highly conserved gene frequently utilized in phylogenetic analyses (18, 22, 29), from the genomic DNA of the African murid samples in our possession. We then aligned these sequences with Rbp3 sequences from the other rodents and generated a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3B; see Data Set S4 in the supplemental material). As shown in Fig. 3B, a maximum-likelihood tree generated using Rbp3 sequences is very similar to the one generated using Fv1 (compare Fig. 3A and B). Rbp3 from what was originally identified as Mylomys dybowskii also clustered outside the subfamily Murinae with a member of the subfamily Gerbillinae (Fig. 3B). A BLAST search of the NCBI nucleotide collection database using the partial exon 1 of Rbp3 from this sample as a probe revealed >98% identity to sequences from several species from the genus Gerbilliscus. Hence, we relabeled this sample Gerbilliscus sp. (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Phylogeny of Fv1 and Rbp3. Maximum-likelihood trees were generated with RaxML using aligned Fv1 (A) and Rbp3 (B) sequences from the indicated rodent species. Bootstrap values are shown next to each node. Each tree was rooted with Nannospalax galili. *, sample was originally identified as Mylomys dybowskii and then renamed Gerbilliscus sp. based on its Rbp3 sequence; **, sequence obtained from the NCBI database. Family and subfamily classifications for a subset of species are indicated on the right of each tree.

Results from these phylogenetic analyses confirmed the identification of an Fv1 ORF in 6 species of the subfamily Murinae outside the genus Mus, as well as two species in the family Muridae, Lophuromys sikapusi and Lophuromys flavopunctatus, indicating that Fv1 coding potential extends outside the subfamily Murinae.

Rapid evolution of Fv1 in African murids.

Genes can evolve under negative (purifying) selection to retain function or under positive (diversifying) selection, which results in adaptive mutational changes. These different evolutionary pathways are defined by the ratio of the rate of nonsynonymous (amino acid-altering; dN) and synonymous (amino acid-preserving; dS) substitutions in related species (30, 31). The vast majority of genes in mammalian genomes are under negative selection, with dN/dS (ω) values well below 1, as amino acid-changing substitutions are less likely to be tolerated (30). On the other hand, host genes that are involved in the antagonism of pathogens, such as Fv1, are found to have experienced positive (or diversifying) selection, with dN/dS values above 1. Such genes are said to be involved in an “arms race” with pathogens with which they interact (30–32).

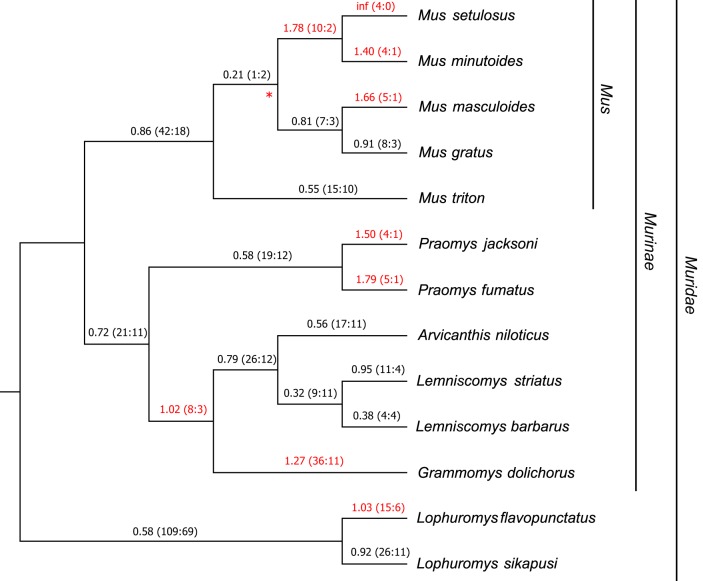

We have previously shown that Fv1 displays signatures of positive selection in the genus Mus (17). However, as our present analysis has shown so far, Fv1 had apparently retained full coding potential for millions of years before the appearance of the genus Mus (see Data Set S3 in the supplemental material). We extended this positive-selection analysis of Fv1 to include other clades in the family Muridae. Since all our genomic-DNA samples were obtained from species with overlapping ranges in sub-Saharan Africa (28), this presented us with a unique opportunity to study Fv1 evolution in a specific geographical location. Hence, for this expanded analysis of positive selection, we combined our sample set of African murids with five other species in the genus Mus, subgenus Nannomys. These murids also have ranges in sub-Saharan Africa (28). Using aligned Fv1 sequences from these species, a maximum-likelihood tree was generated (Fig. 4; see Data Set S5 in the supplemental material). Next, the free-ratio model of PAML (Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood) was used to calculate dN/dS values in each branch (33). As shown in Fig. 4, several branches of the tree showed dN/dS values of >1, including those outside the genus Mus. This result suggests that Fv1 genes from several species, including Grammomys dolichurus, several species in the African clade of the genus Mus, two species in the genus Praomys, and a species in the family Muridae, Lophuromys flavopunctatus, are evolving under positive selection.

FIG 4.

Evolution of Fv1 in African murids. A cladogram obtained using aligned Fv1 sequences from 13 African species of Muridae was generated with RaxML. The free-ratio model of PAML was used to calculate the dN/dS values shown above each branch with the replacement and synonymous changes in parentheses. The values on the branches under positive selection (dN/dS > 1) are highlighted in red. The asterisk indicates the only branch with a bootstrap value of <80. Genus, family, and subfamily classifications for a subset of species are indicated on the right of the tree.

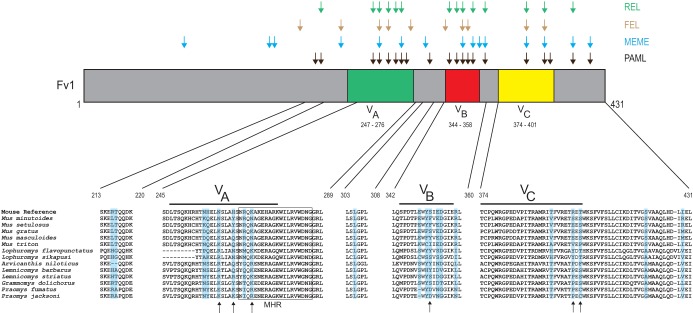

To detect recurrent positive selection at specific amino acid residues of Fv1 from African murids, we utilized four programs: PAML, MEME, REL, and FEL (33–36). The codon-based sites model implemented in the codeml program of PAML revealed that Fv1 from these species is evolving under positive selection, since codon models that allowed positive selection (dN/dS > 1) fit our data significantly better than models that did not allow positive selection (P < 0.000001) (Table 2). Moreover, Bayes empirical Bayes (BEB) analysis of posterior probabilities identified 20 amino acid residues under positive selection with a posterior probability of >0.95 (Table 2) (37). Subsets of these 20 were also identified by MEME (14 sites), FEL (10 sites), and REL (14 sites) (Table 3). A total of 17 sites were found to be under positive selection by at least 2 different programs (Table 3 and Fig. 5), and 4 sites (258H, 352S, 393T, and 399R) were found to be under positive selection by all 4 programs (Fig. 5). Interestingly, 3 of these 4 sites (258H, 352S, and 399R) were previously reported to be under positive selection in Mus (17), and 2 additional sites in the broader set of 20, 270K and 401T, were also among the 6 sites under positive selection in Mus (Fig. 5).

TABLE 2.

PAML analysis of Fv1 from African murids

| ω0a | Codon frequency | M1-M2 |

M7-M8 |

Tree lengthc | dN/dS (%) | Residuesd with dN/dS of >1 and prg of >0.95 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2δb | P value | 2δ | P value | |||||

| 0.4 | f3 × 4 | 76.7 | <0.000001 | 80.6 | <0.000001 | 1.57915 | 7.94 (3.4) | 216Re, 217Te, 257Nf, 258Hf, 261Ne, 265Hf, 268Rf, 270Ke, 305Le, 349Ef, 351Ye, 352Sf, 354Ee, 355Df, 359Re, 393Te, 399Rf, 401Te, 419Se, 429Ie |

| 1.8 | f3 × 4 | 76.7 | <0.000001 | 80.6 | <0.000001 | 1.57915 | 7.94 (3.4) | 216Re, 217Te, 257Nf, 258Hf, 261Ne, 265Hf, 268Rf, 270Ke, 305Le, 349Ef, 351Ye, 352Sf, 354Ee, 355Df, 359Re, 393Te, 399Rf, 401Te, 419Se, 429Ie |

| 0.4 | f61 | 75.9 | <0.000001 | 78 | <0.000001 | 1.51197 | 7.77 (3.2) | 11Se, 21Ee, 138Ee, 216Re, 217Te, 257Nf, 258Hf, 261Nf, 265Hf, 268Rf, 270Ke, 305Le, 344Se, 349Ef, 351Ye, 352Sf, 354Ef, 355Df, 359Re, 393Te, 399Rf, 401Te, 428Le, 429Ie |

| 1.8 | f61 | 75.9 | <0.000001 | 78 | <0.000001 | 1.51197 | 7.77 (3.2) | 11Se, 21Ee, 138Ee, 216Re, 217Te, 257Nf, 258Hf, 261Nf, 265Hf, 268Rf, 270Ke, 305Le, 344Se, 349Ef, 351Ye, 352Sf, 354Ef, 355Df, 359Re, 393Te, 399Rf, 401Te, 428Le, 429Ie |

ωo denotes the initial seed value of ω used.

2δ, two times the difference of the natural log values of the maximum likelihood from pairwise comparisons of the different models.

Tree length is defined as the sum of the nucleotide substitutions per codon at each branch.

Residue numbers are based on the Fv1 found in the Mouse Reference Genome (NP_034374).

P > 0.95.

P > 0.99.

pr, posterior probability.

TABLE 3.

Positively selected residues of Fv1 identified by four different programs

| Amino acid residuea | Selection programd |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAML | MEME | FEL | REL | |

| 46V | − | + | − | − |

| 164A | − | + | − | − |

| 165R | − | + | − | − |

| 198V | − | − | + | − |

| 216R | + | − | − | − |

| 217T | + | − | − | + |

| 240T | − | + | + | − |

| 257N | + | − | − | + |

| 258Hb | + | + | + | + |

| 261Nc | + | − | + | + |

| 265H | + | − | − | + |

| 268Rc | + | + | − | + |

| 270Kc | + | − | − | − |

| 271A | − | − | + | − |

| 302P | − | + | − | − |

| 305L | + | − | − | − |

| 344S | − | − | + | − |

| 349Ec | + | − | − | + |

| 351Y | + | − | − | + |

| 352Sb,c | + | + | + | + |

| 354E | + | − | + | − |

| 355D | + | + | − | + |

| 359R | + | + | − | + |

| 393Tb | + | + | + | + |

| 399Rb | + | + | + | + |

| 401T | + | − | − | − |

| 419S | + | + | − | + |

| 429I | + | + | − | − |

Residues refer to the Fv1 found in the Mouse Reference Genome (NP_034374).

Residue was found to be under positive selection by all four programs.

Residue was previously identified as important in restriction of MLV, EIAV, and FFV.

+, positive; −, negative.

FIG 5.

Positive selection of Fv1 in African murids. A graphical representation of the Fv1 protein is shown, with highlighting to indicate the three variable regions previously identified as important in restriction (16). Amino acid residues that were identified as evolving under positive selection by four programs are shown above the Fv1 protein with differently colored arrows. Amino acid alignment of five segments of Fv1 in African murids (with Fv1 from the Mouse Reference Genome on top) are shown below, with residues under positive selection (as identified by PAML) shaded blue. The arrows below the alignments indicate previously identified positively selected sites in the genus Mus (17). The MHR of Fv1 is boxed.

Over the years, several studies on Fv1 identified multiple residues and regions involved in restriction activity (13, 14, 16). Our analysis shows that most of the positively selected residues of Fv1, identified through PAML, in African murids (14/20) are concentrated in three regions in the C-terminal half of the gene, previously named variable regions A to C (VA to VC) (Fig. 5) (16) on the basis of sequence variants in Mus. One of these regions (VA) overlaps the conserved major homology region (MHR), found in all retroviral capsids, which contains 2 positively selected residues (268R and 270K) (17, 38). Moreover, all 6 residues that we previously found to be under positive selection in Mus (17) were identified as evolving under positive selection in our expanded sample set of African murids (Fig. 5). Taken together, these data suggest that Fv1 has evolved under positive selection in African murids, and there is a significant overlap between positively selected residues of Fv1 and residues previously determined to have significant functional impact (14, 16).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified previously unreported Fv1 orthologs in the rodent families Muridae, Cricetidae, and Spalacidae. These families are thought to have evolved separately for approximately 45 million years (18–20, 22, 27). This suggests a minimum insertion time of 45 million years for the presumed proviral progenitor of Fv1. This time estimate can be expanded to 55 million years to include all of the suborder Myomorpha. None of the species studied here contained an expanded ERV at the Fv1 site or an Fv1-like ERV elsewhere in their genomes. However, use of RepeatMasker indicated that Nannospalax galili has repetitive elements surrounding the Fv1 site that appear to be the remnants of an ERV-L like element (data not shown). While this element was far too fragmented to reconstruct a recognizable provirus, this finding opens the possibility that further study of the region around Fv1 or the ERV-L sequences in other rodent lineages may lead to the identification of the ancient provirus that gave rise to Fv1. It will be particularly interesting to analyze the sequences around Fv1 orthologs in other members of the family Spalacidae to determine whether a more intact ERV-L element can be identified.

ERVs comprise a large component of vertebrate genomes, determined to be 10% in the mouse genome (39). While most of these ERVs are nonfunctional and contain mutations and indels, over the course of vertebrate evolution, some components of ERVs have been coopted for host cell functions (4, 40, 41). The most prominent example of such cooption are the syncytins, env genes of ERVs that function in placenta formation (40). In Myomorpha, a suborder of rodents, two syncytins have been traced to the common ancestor of the families Spalacidae, Cricetidae, and Muridae, making it the oldest ERV with a coopted ORF in rodents (42). Our studies suggest a similar insertion time frame for the acquisition of Fv1 (Fig. 1). However, unlike syncytins, most of the species in the genome database that contained an Fv1 ortholog did not have a full-length ORF. In fact, several species in the family Cricetidae did not have an identifiable Fv1 ortholog at all in their genomes. With increased availability of whole-genome sequences, it has become apparent that gene loss is an evolutionary phenomenon observed in many lineages (43). In the case of Fv1, an intronless remnant of an ERV, its function as an innate restriction factor that antagonizes retroviruses suggests the possibility that the lineages that lost Fv1 either did not encounter or were not significantly threatened by a retrovirus subject to Fv1 restriction. In the absence of selection pressure, Fv1 would be expected to have the same fate as other nonfunctional ERVs, that is, annihilation by the accumulation of progressive mutations (39). It is important to note that, while our database searches suggested loss of Fv1 in a variety of species (Fig. 1), some of these genome assemblies have higher-level coverage/completeness than others (Table 1). Hence, further studies are required to obtain a complete picture of Fv1 loss in different subfamilies or genera belonging to the superfamily Muroidea.

In this study, we expanded our previous demonstration that Fv1 is under positive selection in Mus by analyzing several species belonging to the family Muridae outside the genus Mus that are indigenous to sub-Saharan Africa (17, 28). We found substantially more positively selected amino acid sites in this subset than in the genus Mus (Fig. 5 and Table 3). This is likely due to the fact that the species included in our current study encompass a much larger evolutionary timeline and that multiple residues, especially in the Fv1 variable regions, can influence antiviral activity. Our findings indicate that Fv1 sequences from African murids are under intense selection pressure and have likely been antagonized by multiple retroviruses over the course of their evolution. Further study of the potential restriction function of these newly identified Fv1 orthologs from African murids using known retroviruses may or may not reveal useful information for the evolution of Fv1 in these species. The retroviruses encountered by these animals during their evolution are unknown and may no longer be extant, so we may not be able to identify retroviruses that may have been engaged in an arms race with Fv1 during the course of their coevolution.

Fv1 was originally identified in inbred laboratory strains as a restriction factor against MLVs, a group of gammaretroviruses that are found only in subspecies of M. musculus (10, 44, 45). However, later studies identified functionally active Fv1 in species that do not harbor these viruses (16, 17). In concert with this finding, Fv1s from different species of the genus Mus were shown to have restriction activity against retroviruses other than MLV, such as feline foamy virus (FFV) and EIAV (16). That study also identified several polymorphic residues in Fv1 (amino acids 261, 268, 270, 349, and 352) that had a substantial impact on restriction of these viruses. In our analysis of Fv1 evolution in African murids, we demonstrated that all 5 of the amino acid residues implicated in the Fv1 restriction of FFV and EIAV are under positive selection (Table 3). In the laboratory mouse Fv1 variants, all three residue differences are associated with resistance, but only two of the three are under positive selection in the genus Mus; interestingly, the residue with the largest impact on the relative restriction of N- versus B-tropic viruses, 358K, is not under positive selection in the genus Mus or in other murids (13, 14, 17). This restriction is associated with a single substitution, K358E, in M. musculus, and the failure to identify this mutation in other species suggests that the polymorphism is retrovirus target specific. The present analysis underscores the power of this type of evolutionary analysis to identify functionally important residues in host proteins that have antagonistic relationships with pathogens.

Despite decades of functional and genetic studies, the mechanism of Fv1 restriction of MLVs has not been determined. While these studies revealed that Fv1 targets the viral capsid, we have no structural details of this interaction, as Fv1 has not been amenable to structural resolution (11, 46, 47). The expanded evolutionary history of Fv1 we present in this study will likely open new avenues of research. These include investigations of restriction of various known and newly described retroviruses by Fv1 found in species outside the genus Mus, as well as structural studies to describe the physical interaction of these Fv1 proteins with the viral capsid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rodent genome sources.

Thirty-four rodent genome assemblies in the NCBI database were used for database searches for Fv1 orthologs and for extraction of Rbp3 exon 1 sequences (Table 1). Genomic-DNA samples from African murids collected in Uganda were a kind gift from Peter D'Eustachio and Yvonne Cole (New York University, New York, NY) (48). Fv1 sequences from African pygmy mice were obtained from the GenBank database with the following accession numbers: Mus triton, FJ603557; Mus gratus, FJ603556; Mus setulosus, FJ603555; Mus minutoides, FJ603554; Mus musculoides, FJ603558 (17). Genomic DNA from E36 (Cricetulus griseus), BHK (Mesocricetus auratus), and GeLu (Meriones unguiculatus) cells were isolated with a PureLink DNA minikit (Thermo Fisher) following the manufacturer's instructions. GeLu cells (ATCC CCL-100) were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA), and BHK cells were from M. Eiden (NIMH, Bethesda, MD).

Database search for Fv1 orthologs.

The Fv1 ORF sequence from the mouse reference assembly (NM_010244) was used as a probe in a BLAST search (49, 50) of 34 individual rodent genome assemblies housed in the NCBI database (Table 1). The following parameters were used for BLASTn: gap costs, 5 and 2 (existence and extension); match/mismatch scores, +2/−3; repeat masking filter turned off; Expect threshold, 10−20.

Fv1 and Rbp3 cloning and sequencing.

PCRs were performed using AmpliTaq Gold (Thermo Fisher) with the following program: 95°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s; and 72°C for 5 min.

Fv1 and its flanking regions were amplified from the genomic DNA of various African murids using the following primers: 5′ AAG ATG AAT TTC CHH CGT GCG CTT 3′ and 5′ CTC YTT AAC TGW TGC TTT GRT RTT YMC AGG 3′. The primers used for amplification of Rbp3 from African murids were 119A2, 5′ GTC CTC TTG GAT AAC TAC TGC TT 3′, and 878F, 5′ CTC CAC TGC CCT CCC ATG TCT 3′ (21). The primers used for amplification of the Fv1 flanking region from the genomic DNAs obtained from E36, BHK, and Gelu cells were E36, 5′ TCC TGC AGC GAA GAC TTA GA 3′ and 5′ GTG GCC TTC TAG CCC CTC TTA 3′; BHK, 5′ CCT GCA GCA GCG ACT TAG AAT 3′ and 5′ ACC TCG TAG TGA AAA GTT CCT ACA C 3′; Gelu, 5′ GGA TCC GAA GCT TTG CAG GAC 3′ and 5′ GTA GAG AGA AGC TGC AGT AGG G 3′. PCR products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and cloned into the PCR 2.1 TOPO (Thermo Fisher) plasmid before sequencing.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis.

For the alignment of the genomic region around Fv1, two strategies were utilized. For the genomes that have been annotated, the DNA sequence that encompassed the genes Miip and Mfn2, based on the annotation, was extracted from the GenBank database. For genomes without annotation, BLASTn was used with mouse genomic DNA as a probe to search for the contig/scaffold that contained both Miip and Mfn2, and sequences encompassing these genes were extracted. MultiPipMaker was used for aligning genomic sequences (25).

Fv1 and Rbp3 sequences were aligned using MUSCLE as implemented in Geneious 10.0.9 using default settings (51, 52). Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees were generated using the RaxML program with the GTR + G + I model and 500 bootstraps for branch support (53). Sequence alignments were not manually adjusted for construction of phylogenetic trees except for the trees generated for positive-selection analysis, as described below.

Positive-selection analysis.

For maximum-likelihood analysis of codon evolution, we used codeml of PAML 4.9, in addition to three programs on the DataMonkey Web server: MEME, REL, and FEL (33–36). Aligned Fv1 sequences from African murids were manually inspected to exclude any indels that occurred in more than a few species, as recommended by the developers of PAML. The first 21 nucleotides, due to the location of the forward primer used for amplification, as well as nucleotides past the stop codon of Mus triton, were excluded from analysis. The DNA sample that was initially identified as being from Mylomys dybowskii (here reclassified as Gerbilliscus sp.) was excluded from positive-selection analysis, as it contained an early stop codon. To calculate branch-specific dN/dS values, we utilized the free-ratio model in codeml. To detect specific codons under positive selection, F61 and F3x4 codon frequency models in codeml of PAML 4.9 were used, with different initial seed values of ω. Likelihood ratio tests were performed to compare two pairs of site-specific models: M1, a neutral model that does not allow positive selection, was compared to M2, a model that allows positive selection, and M7, another neutral model with beta distribution of dN/dS values, was compared to M8, a positive-selection model with beta distribution. In each case, chi-square analysis was done, and a model that allowed positive selection was a significantly better fit to the data than the null (neutral) model (P < 0.000001). Posterior probabilities of codons under positive selection were inferred using the BEB algorithm in the M8 model (37) (Table 2). Alternative tests for positive-selection analyses were performed using the MEME, FEL, and REL programs with recommended settings (34) and the following selection criteria for identification of positively selected residues: MEME, P < 0.1; FEL, P < 0.1; and REL, Bayes factor > 50.

Accession number(s).

The Fv1 and Rbp3 sequences are available in GenBank under accession numbers MH270640 to MH270660.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD.

We thank Peter d'Eustachio and Yvonne Cole for the kind gift of African murid DNAs.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00850-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiewsakun P, Katzourakis A. 2017. Marine origin of retroviruses in the early Palaeozoic Era. Nat Commun 8:13954. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatziioannou T, Bieniasz PD. 2011. Antiretroviral restriction factors. Curr Opin Virol 1:526–532. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lilly F. 1967. Susceptibility to two strains of Friend leukemia virus in mice. Science 155:461–462. doi: 10.1126/science.155.3761.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Best S, Le Tissier P, Towers G, Stoye JP. 1996. Positional cloning of the mouse retrovirus restriction gene Fv1. Nature 382:826–829. doi: 10.1038/382826a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benit L, De Parseval N, Casella JF, Callebaut I, Cordonnier A, Heidmann T. 1997. Cloning of a new murine endogenous retrovirus, MuERV-L, with strong similarity to the human HERV-L element and with a gag coding sequence closely related to the Fv1 restriction gene. J Virol 71:5652–5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozak CA. 1985. Analysis of wild-derived mice for Fv-1 and Fv-2 murine leukemia virus restriction loci: a novel wild mouse Fv-1 allele responsible for lack of host range restriction. J Virol 55:281–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartley JW, Rowe WP, Huebner RJ. 1970. Host-range restrictions of murine leukemia viruses in mouse embryo cell cultures. J Virol 5:221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung YT, Kozak CA. 2000. A single amino acid change in the murine leukemia virus capsid gene responsible for the Fv1nr phenotype. J Virol 74:5385–5387. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.11.5385-5387.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qi CF, Bonhomme F, Buckler-White A, Buckler C, Orth A, Lander MR, Chattopadhyay SK, Morse HC III. 1998. Molecular phylogeny of Fv1. Mamm Genome 9:1049–1055. doi: 10.1007/s003359900923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowe WP. 1972. Studies of genetic transmission of murine leukemia virus by AKR mice. I. Crosses with Fv-1n strains of mice. J Exp Med 136:1272–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozak CA, Chakraborti A. 1996. Single amino acid changes in the murine leukemia virus capsid protein gene define the target of Fv1 resistance. Virology 225:300–305. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens A, Bock M, Ellis S, LeTissier P, Bishop KN, Yap MW, Taylor W, Stoye JP. 2004. Retroviral capsid determinants of Fv1 NB and NR tropism. J Virol 78:9592–9598. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9592-9598.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bock M, Bishop KN, Towers G, Stoye JP. 2000. Use of a transient assay for studying the genetic determinants of Fv1 restriction. J Virol 74:7422–7430. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.16.7422-7430.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishop KN, Bock M, Towers G, Stoye JP. 2001. Identification of the regions of Fv1 necessary for murine leukemia virus restriction. J Virol 75:5182–5188. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5182-5188.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang WK, Kiggans JO, Yang DM, Ou CY, Tennant RW, Brown A, Bassin RH. 1980. Synthesis and circularization of N- and B-tropic retroviral DNA Fv-1 permissive and restrictive mouse cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:2994–2998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yap MW, Colbeck E, Ellis SA, Stoye JP. 2014. Evolution of the retroviral restriction gene Fv1: inhibition of non-MLV retroviruses. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003968. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan Y, Buckler-White A, Wollenberg K, Kozak CA. 2009. Origin, antiviral function and evidence for positive selection of the gammaretrovirus restriction gene Fv1 in the genus Mus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:3259–3263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900181106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabre PH, Hautier L, Dimitrov D, Douzery EJP. 2012. A glimpse on the pattern of rodent diversification: a phylogenetic approach. BMC Evol Biol 12:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schenk JJ, Rowe KC, Steppan SJ. 2013. Ecological opportunity and incumbency in the diversification of repeated continental colonizations by muroid rodents. Syst Biol 62:837–864. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedges SB, Marin J, Suleski M, Paymer M, Kumar S. 2015. Tree of life reveals clock-like speciation and diversification. Mol Biol Evol 32:835–845. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alhajeri BH, Hunt OJ, Steppan SJ. 2015. Molecular systematics of gerbils and deomyines (Rodentia: Gerbillinae, Deomyinae) and a test of desert adaptation in the tympanic bulla. J Zool Syst Evol Res 53:312–330. doi: 10.1111/jzs.12102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steppan SJ, Schenk JJ. 2017. Muroid rodent phylogenetics: 900-species tree reveals increasing diversification rates. PLoS One 12:e0183070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao W, Kojima KK, Kohany O. 2015. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob DNA 6:11. doi: 10.1186/s13100-015-0041-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alkan C, Coe BP, Eichler EE. 2011. Genome structural variation discovery and genotyping. Nat Rev Genet 12:363–376. doi: 10.1038/nrg2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elnitski L, Burhans R, Riemer C, Hardison R, Miller W. 2010. MultiPipMaker: a comparative alignment server for multiple DNA sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics Chapter 10:Unit 10.4. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1004s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adkins RM, Walton AH, Honeycutt RL. 2003. Higher-level systematics of rodents and divergence time estimates based on two congruent nuclear genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol 26:409–420. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S, Stecher G, Suleski M, Hedges SB. 2017. TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol Biol Evol 34:1812–1819. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson DE, Reeder DM. 2005. Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference, 3rd ed Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weksler M. 2003. Phylogeny of neotropical oryzomyine rodents (Muridae: Sigmodontinae) based on the nuclear IRBP exon. Mol Phylogenet Evol 29:331–349. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyerson NR, Sawyer SL. 2011. Two-stepping through time: mammals and viruses. Trends Microbiol 19:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daugherty MD, Malik HS. 2012. Rules of engagement: molecular insights from host-virus arms races. Annu Rev Genet 46:677–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duggal NK, Emerman M. 2012. Evolutionary conflicts between viruses and restriction factors shape immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 12:687–695. doi: 10.1038/nri3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang ZH. 2007. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol 24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delport W, Poon AF, Frost SD, Kosakovsky Pond SL. 2010. Datamonkey 2010: a suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics 26:2455–2457. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murrell B, Wertheim JO, Moola S, Weighill T, Scheffler K, Kosakovsky Pond SL. 2012. Detecting individual sites subject to episodic diversifying selection. PLoS Genet 8:e1002764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Frost SD. 2005. Not so different after all: a comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol Biol Evol 22:1208–1222. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z, Wong WS, Nielsen R. 2005. Bayes empirical Bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol Biol Evol 22:1107–1118. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kingston RL, Vogt VM. 2005. Domain swapping and retroviral assembly. Mol Cell 17:166–167. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stocking C, Kozak CA. 2008. Murine endogenous retroviruses. Cell Mol Life Sci 65:3383–3398. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lavialle C, Cornelis G, Dupressoir A, Esnault C, Heidmann O, Vernochet C, Heidmann T. 2013. Paleovirology of 'syncytins', retroviral env genes exapted for a role in placentation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368:20120507. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malfavon-Borja R, Feschotte C. 2015. Fighting fire with fire: endogenous retrovirus envelopes as restriction factors. J Virol 89:4047–4050. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03653-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vernochet C, Redelsperger F, Harper F, Souquere S, Catzeflis F, Pierron G, Nevo E, Heidmann T, Dupressoir A. 2014. The captured retroviral envelope syncytin-A and syncytin-B genes are conserved in the Spalacidae together with hemotrichorial placentation. Biol Reprod 91:148. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.124818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma V, Hecker N, Roscito JG, Foerster L, Langer BE, Hiller M. 2018. A genomics approach reveals insights into the importance of gene losses for mammalian adaptations. Nat Commun 9:1215. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03667-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowe WP, Hartley JW. 1972. Studies of genetic transmission of murine leukemia virus by AKR mice. II. Crosses with Fv-1 b strains of mice. J Exp Med 136:1286–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kozak CA, O'Neill RR. 1987. Diverse wild mouse origins of xenotropic, mink cell focus-forming, and two types of ecotropic proviral genes. J Virol 61:3082–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor WR, Stoye JP. 2004. Consensus structural models for the amino terminal domain of the retrovirus restriction gene Fv1 and the murine leukaemia virus capsid proteins. BMC Struct Biol 4:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hilditch L, Matadeen R, Goldstone DC, Rosenthal PB, Taylor IA, Stoye JP. 2011. Ordered assembly of murine leukemia virus capsid protein on lipid nanotubes directs specific binding by the restriction factor, Fv1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:5771–5776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100118108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cole YI. 1992. Systematics and ecogenetics of East African murids. Ph.D. dissertation. New York University, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.