Influenza vaccine strains must be updated frequently since circulating viral strains continuously change in antigenically important epitopes. Our previous studies have demonstrated that some individuals possess antibody responses that are narrowly focused on epitopes that were present in viral strains that they encountered during childhood. Here, we show that influenza viruses rapidly escape this type of polyclonal antibody response when grown in ovo by acquiring single mutations that directly prevent antibody binding. These studies improve our understanding of how influenza viruses evolve when confronted with narrowly focused polyclonal human antibodies.

KEYWORDS: antibody, influenza, mutation

ABSTRACT

Influenza viruses use distinct antibody escape mechanisms depending on the overall complexity of the antibody response that is encountered. When grown in the presence of a hemagglutinin (HA) monoclonal antibody, influenza viruses typically acquire a single HA mutation that reduces the binding of that specific monoclonal antibody. In contrast, when confronted with mixtures of HA monoclonal antibodies or polyclonal sera that have antibodies that bind several HA epitopes, influenza viruses acquire mutations that increase HA binding to host cells. Recent data from our laboratory and others suggest that some humans possess antibodies that are narrowly focused on HA epitopes that were present in influenza virus strains that they were likely exposed to in childhood. Here, we completed a series of experiments to determine if humans with narrowly focused HA antibody responses are able to select for influenza virus antigenic escape variants in ovo. We identified three human donors that possessed HA antibody responses that were heavily focused on a single HA antigenic site. Sera from all three of these donors selected single HA escape mutations during in ovo passage experiments, similar to what has been previously reported for single monoclonal antibodies. These single HA mutations directly reduced binding of serum antibodies used for selection. We propose that new antigenic variants of influenza viruses might originate in individuals who produce antibodies that are narrowly focused on HA epitopes that were present in viral strains that they encountered in childhood.

IMPORTANCE Influenza vaccine strains must be updated frequently since circulating viral strains continuously change in antigenically important epitopes. Our previous studies have demonstrated that some individuals possess antibody responses that are narrowly focused on epitopes that were present in viral strains that they encountered during childhood. Here, we show that influenza viruses rapidly escape this type of polyclonal antibody response when grown in ovo by acquiring single mutations that directly prevent antibody binding. These studies improve our understanding of how influenza viruses evolve when confronted with narrowly focused polyclonal human antibodies.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza viruses continuously acquire mutations in antigenically important regions of the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins through a process termed antigenic drift (1). Most humans are infected with influenza viruses in childhood (2) and then are continuously reinfected with antigenically distinct strains later in life (3). Early childhood influenza virus infections can leave lifelong immunological imprints that can influence how an individual subsequently responds to antigenically distinct influenza virus strains (4, 5). Antibody (Ab) responses in some individuals can become heavily focused on HA epitopes that are conserved between contemporary viral strains and strains that they encountered in childhood (4). It is thought that memory B cells established from childhood infections are continuously recalled later in life upon infection with new influenza virus strains that possess some shared epitopes (4).

Seasonal influenza vaccines need to be continually updated because of antigenic drift (6). Understanding the specificity of common human anti-influenza virus antibodies is important to guide the selection of appropriate seasonal vaccine strains. Selection of appropriate vaccine strains also requires a deep mechanistic understanding of how influenza viruses escape human antibodies. Multiple studies suggest that influenza viruses utilize distinct escape mechanisms depending on the complexity of the antibody response they encounter (as reviewed in reference 1). For example, influenza viruses grown in vitro or in ovo in the presence of a single HA monoclonal antibody rapidly acquire single HA mutations that prevent the binding of the selecting monoclonal antibody (7). In contrast, viruses grown in vitro in the presence of multiple HA monoclonal antibodies targeting distinct epitopes (8) or in the presence of polyclonal sera in vivo in mice (9) acquire single HA adsorptive mutations that increase viral attachment to host receptors. Adsorptive mutations do not always directly prevent antibody binding; instead, viruses with stronger binding avidity can circumvent antibodies of various specificities by simply binding to cells more efficiently (8, 9).

It is unknown if some humans possess polyclonal antibodies that are so biased toward a single HA epitope that they select for single antigenic escape variants, similar to what has been previously reported for single monoclonal antibodies. Here, we used hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assays, neutralization assays, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) to identify three human serum samples that possessed anti-H1N1 HA antibodies that were narrowly focused on an epitope that was conserved in an H1N1 strain that circulated during the individuals' childhoods. We sequentially passaged the A/California/07/2009 H1N1 strain in the presence of these serum samples in ovo and characterized the passaged viruses.

(This article was submitted to an online preprint archive [10]).

RESULTS

Identification of individuals who possess narrowly focused anti-H1N1 antibodies.

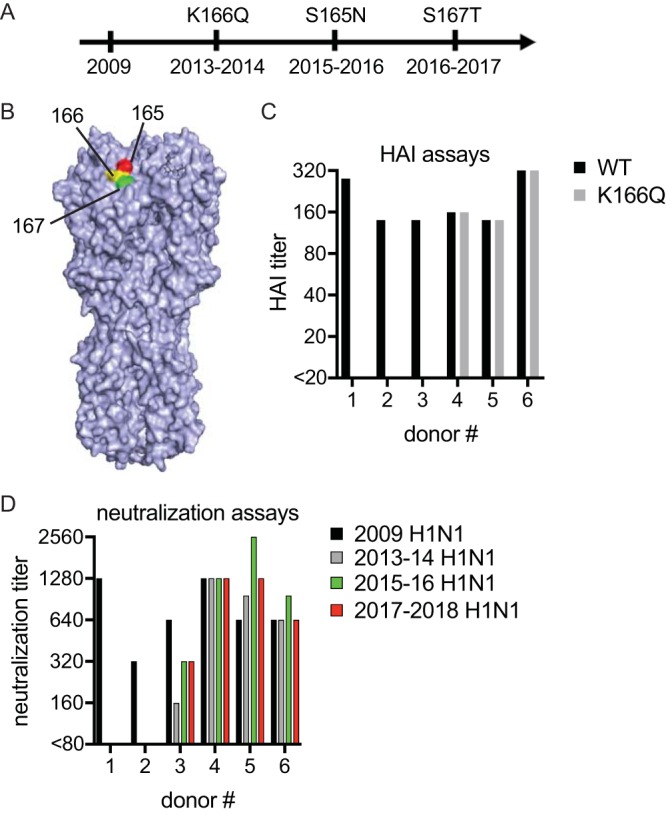

We have previously shown that some individuals born before 1985 possess anti-H1N1 antibodies that target an HA epitope that is conserved between the A/California/07/2009 pandemic H1N1 strain and seasonal H1N1 strains that circulated prior to 1985 (11, 12). This particular antibody specificity appears to be important since contemporary H1N1 strains (which are descendants of the 2009 pandemic strain) have acquired several substitutions in the HA epitope targeted by these antibodies over the past 5 years (Fig. 1A and B). For example, H1N1 viruses acquired a K166Q substitution in this epitope during the 2013-2014 season, an S165N substitution in this epitope during the 2015-2016 season, and an S167T substitution in this epitope during the 2016-2017 season (Fig. 1A and B) (H3 numbering is used throughout the manuscript). While it is clear that antibodies targeting H1N1 HA epitopes involving residues 165 to 167 are unable to recognize H1N1 viruses that are currently circulating among humans, it is unknown whether these antibodies are present in sufficient quantities within single individuals to actually select for HA antigenic escape variants with substitutions at residues 165, 166, and 167.

FIG 1.

Identification of humans with narrowly focused H1N1 antibody responses. (A) H1N1 viruses acquired substitutions at HA residues 165, 166, and 167 since 2009. (B) Residues 165, 166, and 167 of HA are located in close proximity to each other (PDB accession number 3UBN). (C) HAI assays were completed using H1N1-WT and H1N1-K166Q viruses and serum collected from human donors prior to the 2013-2014 season. (D) Neutralization assays were completed using the 2009 H1N1-WT strain and drifted H1N1 strains from 2013 to 2018.

We previously reported that 11% of participants of the 2013-2014 Household Influenza Vaccine Evaluation (HIVE) cohort possessed Abs that reacted in hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assays with the wild-type (WT) A/California/07/2009 strain (H1N1-WT) but not with an A/California/07/2009 strain engineered to possess a K166Q HA mutation (H1N1-K166Q) (12). Here, we analyzed three donors from this cohort that were born prior to 1985 who possessed serum antibodies that had a >4-fold reduction in HAI titers using H1N1-K166Q compared to HAI titers using H1N1-WT (Fig. 1C). We also analyzed three donors that possessed serum antibodies that had similar HAI titers using the H1N1-K166Q and H1N1-WT strains (Fig. 1C). Donor serum antibodies that reacted poorly with the H1N1-K166Q strain in HAI assays had reduced neutralization titers against drifted H1N1 strains isolated from 2013 to 2018, whereas donor serum antibodies that reacted strongly with the H1N1-K166Q strain effectively neutralized these drifted H1N1 strains (Fig. 1D).

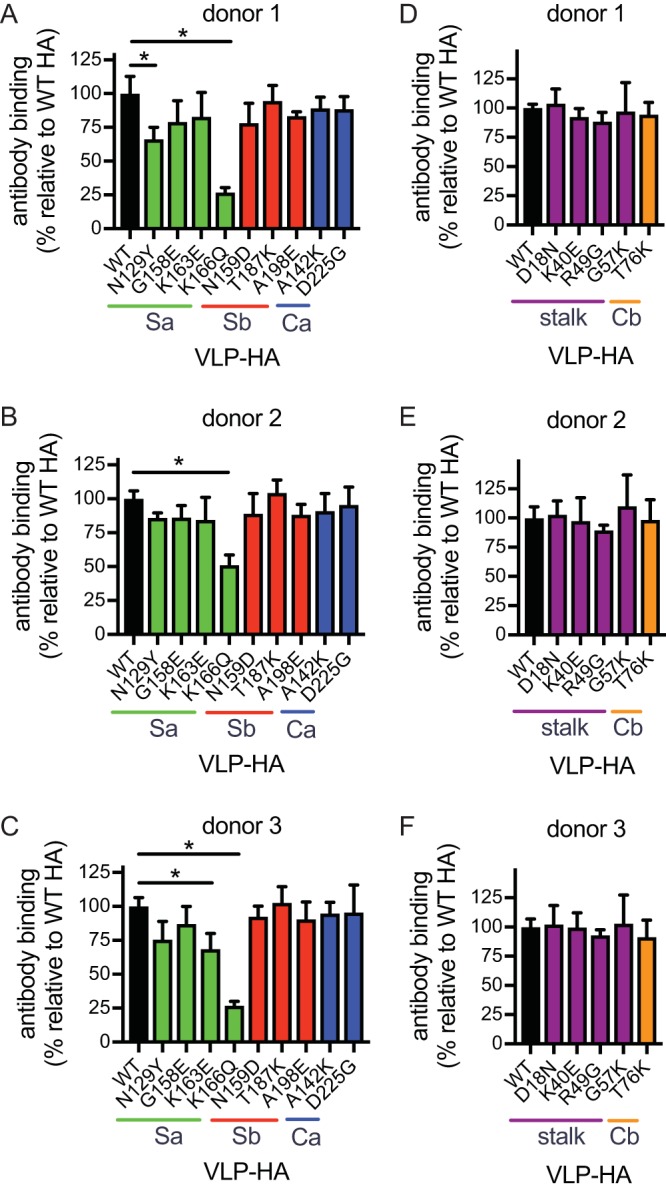

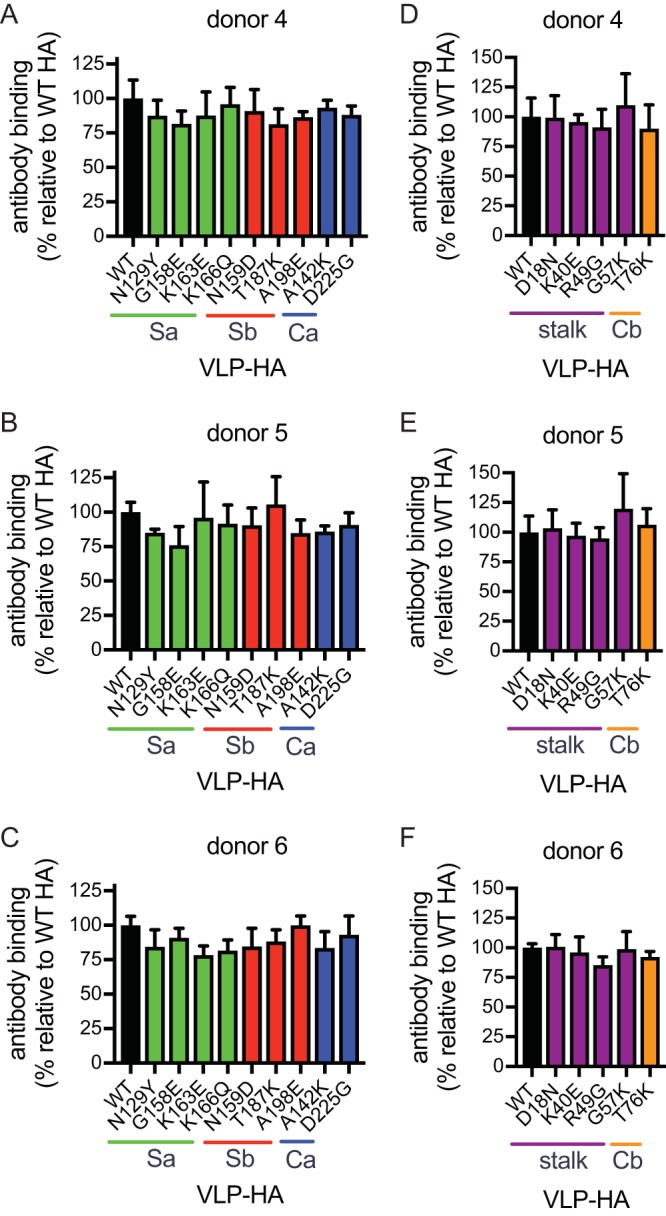

We further characterized each serum sample via ELISAs designed to detect antibodies that bind to both the HA globular head and stalk domains. For ELISAs, we engineered a panel of virus-like particles (VLPs) that possess A/California/07/2009 HA with different single point mutations in the HA head and stalk domains (Fig. 2). In samples from donors 1 to 3, as expected, serum antibodies that reacted poorly with H1N1-K166Q in HAI assays also bound poorly to VLPs possessing HA with the K166Q substitution (Fig. 3A to C). Serum antibodies from donor 1 also had slightly reduced binding to VLPs possessing HA with the N129Y substitution (Fig. 3A), and antibodies from donor 3 had slightly reduced binding to VLPs possessing HA with the K163E mutation (Fig. 3C); both of these residues are adjacent to HA residue 166 (Fig. 2). Serum antibodies from donors with narrowly focused HAI responses did not have reduced binding to VLPs possessing substitutions in the lower globular HA head and stalk domains (Fig. 3D to F). In samples from donors 4 to 6, serum antibodies that had similar HAI titers using the H1N1-K166Q and H1N1-WT viruses did not have reduced binding to any mutant VLPs in our panel, including VLPs possessing HA with the K166Q substitution (Fig. 4A to F). None of the HA substitutions in our VLP panel significantly affected binding of serum antibodies from these three individuals. This could be because these donors possess antibodies that target HA epitopes that are not mutated in our VLP panel. Alternatively, it is possible that these donors have more balanced antibody responses and that our assays are not sensitive enough to detect small reductions in polyclonal antibody binding to each VLP.

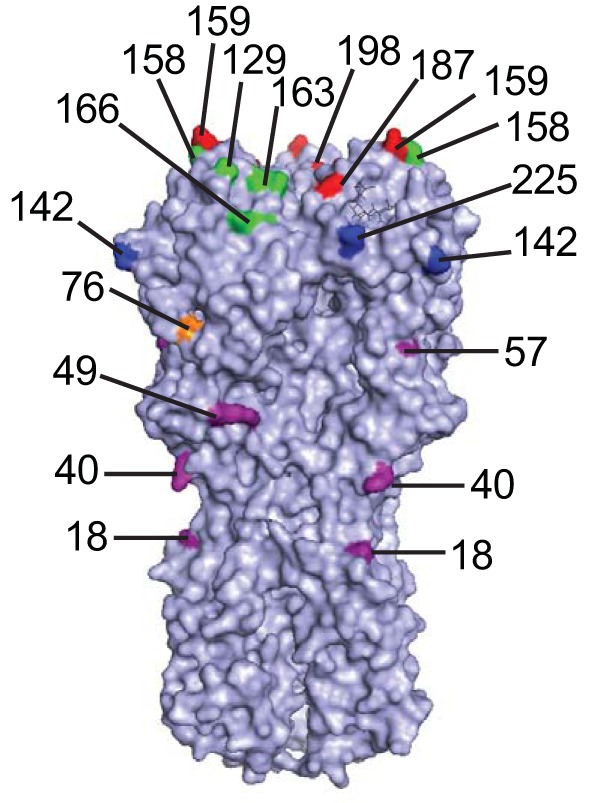

FIG 2.

Distribution of substitutions across different HA antigenic sites in our VLP panel. The HA structure (PDB accession number 3UBN) highlighting substitutions in our VLP panel is shown. Sa residues are shown in green, Sb residues are shown in red, Ca residues are shown in dark blue, Cb residues are shown in orange, and lower HA/stalk residues are shown in purple.

FIG 3.

Antigenic characterization of human serum samples that are narrowly focused on a single HA antigenic site. ELISAs were completed using VLPs with HAs that had substitutions in either the top of the HA globular head (A to C) or lower part of HA (D to F). Antibody binding between different ELISA plates was normalized by including a standard monoclonal on each plate. A series of eight serum dilutions were tested, and data are expressed as percent binding (based on area under the curve) relative to binding to WT HA. Experiments were completed in triplicate. Means and SD from three different experiments are shown. (*, P < 0.05; Dunnett's multiple-comparison test comparing results for VLPs with WT HA to those for VLP with variant HAs.)

FIG 4.

Antigenic characterization of human control serum samples. ELISAs were completed using VLPs with HAs that had substitutions in either the top of the HA globular head (A to C) or lower part of HA (D to F). Antibody binding between different ELISA plates was normalized by including a standard monoclonal on each plate. A series of eight serum dilutions were tested, and data are expressed as percent binding (based on area under the curve) relative to binding to WT HA. Experiments were completed in triplicate. Means and SD from three different experiments are shown.

Sequential passaging of H1N1 in ovo in the presence of human serum samples.

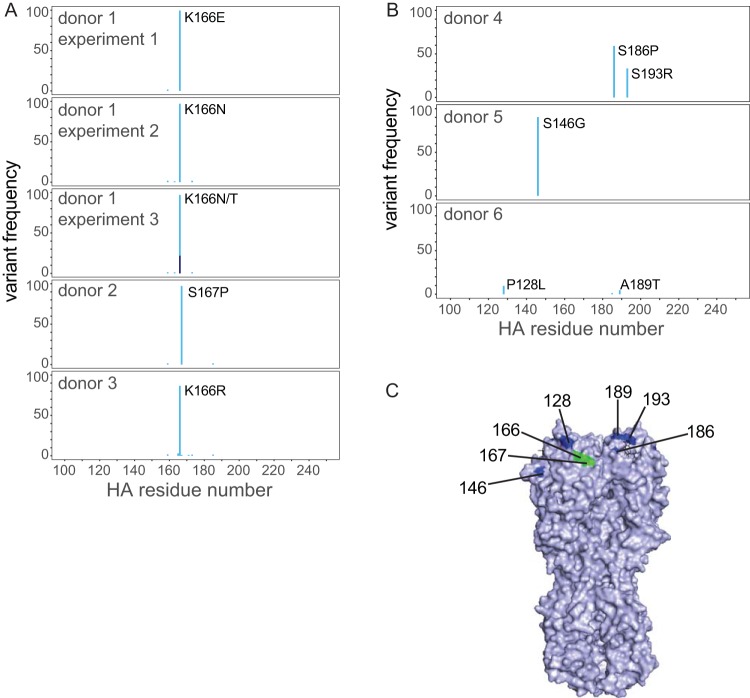

To determine how H1N1 viruses evolve when confronted with narrowly focused serum polyclonal antibody responses, we passaged A/California/07/2009 virus in embryonated chicken eggs in the presence of each serum sample. As a control, we also passaged virus in the absence of serum. After the third passage, we extracted RNA and carried out reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and deep sequencing of each viral isolate. To reduce the influence of sequencing error in variant calling, we produced triplicate independent library preparations and averaged all replicates to determine variant frequencies. We found that viruses passaged in the presence of all three narrowly focused polyclonal serum samples acquired a substitution at >95% frequency at HA residue 166 or 167 (Fig. 5A). Residues 166 and 167 are likely in the same epitope, based on their proximity (Fig. 5C), which is further supported by recent cocrystal structures of a monoclonal antibody with similar binding patterns (13). To investigate intrasample variability, we repeated two additional viral passaging experiments with serum from donor 1. Viruses again acquired substitutions at HA residue 166, but the specific amino acid change was different in the different experiments (Fig. 5A). In contrast to passaging experiments involving narrowly focused sera, viruses grown in the presence of control sera (i.e., sera not affected in HAI assays, neutralization assays, and ELISAs by the K166Q HA mutation) did not acquire substitutions in the HA epitope involving residue 166 (Fig. 5B). Instead, viruses grown in the presence of these sera acquired substitutions at residues 128, 146, 186, 189, and 193 of HA (Fig. 5B and C). Virus grown in the absence of sera did not acquire HA mutations at >2.5% frequency. We detected several mutations in the other seven gene segments of passaged viruses, but there were no obvious mutational patterns that distinguished viruses passaged in narrowly focused sera from those in control sera (Table 1).

FIG 5.

Identification of HA substitutions that arose after passaging. HA variant frequencies in virus passaged in the presence of narrowly focused serum samples (A) and control serum samples (B) are shown. The percentage of each variant is indicated. Different shades of blue indicate different amino acid variants at the same residue. (C) The location of HA mutations that arose after passaging are shown (PDB accession number 3UBN).

TABLE 1.

Identification of mutations in passaged viruses

| Donor and/or replicate | Mutation by gene segment (frequency [%]) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | NA | M | NP | NS | PA | PB1 | PB2 | |

| 1 | ||||||||

| Replicate 1 | K166E (99.4) | I38S (2.6) | E117A (9.6) | |||||

| Replicate 2 | K166N (97.1) | R49I (6.8) | ||||||

| Replicate 3 | K166N (75.0), K166T (22.1) | L74I (2.9) | V520L (18.3) | |||||

| 2 | S167P (97.2), N297S (4.5) | A246T (4.5) | M92P (3.6) | K547R (19.1) | ||||

| 3 | K166R (86.6) | T208K (2.7) | Q297R (8.0) | |||||

| 4 | S186P (59.0), S193R (33.2) | M15T (28.3), I34T (17.0) | Y304C (4.4) | L163I (4.3), R197K (9.3), F341L (4.7) | N116T (3.1) | |||

| 5 | S146G (90.4) | R539T (89.2) | K216R (90.0) | N116S (4.3) | ||||

| 6 | P128L (9.5), A189T (4.7) | I443 M (11.4), T466A (14.0) | V72I (5.0) | I38S (5.6) | V453 M (4.3) | |||

| No-serum control | M415R (4.1) | |||||||

Characterization of individual mutants that arose during in ovo passaging experiments.

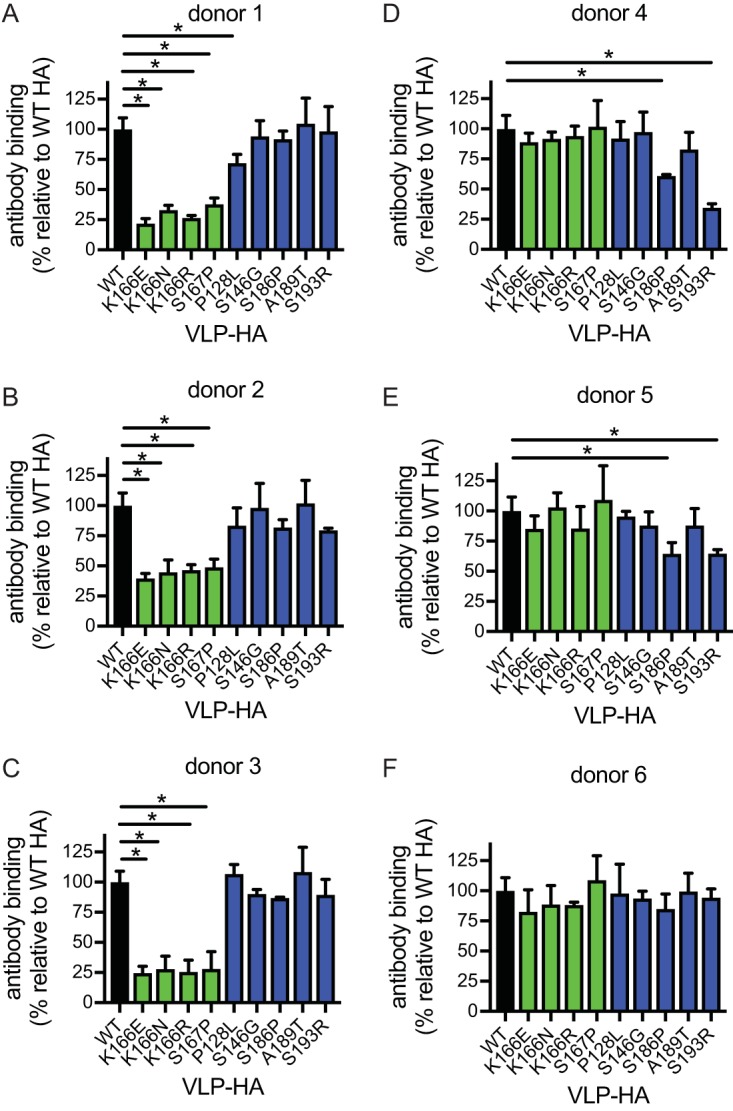

We next created VLPs possessing HA that contained substitutions that were present at >4.5% in our in ovo passaging experiments. We then carried out ELISAs with these VLPs and found that antibodies in serum samples that were narrowly focused on the HA epitope involving residue 166 had reduced binding to all of the variants possessing substitutions at residues 166 and 167 (Fig. 6A to C). Antibodies in these serum samples did not have reduced binding to VLPs possessing substitutions that arose in the presence of control sera (Fig. 6A to C), with the exception of VLPs possessing a substitution at residue 128, which is near residue 166 of HA (Fig. 5C). Substitutions at residues 166 and 167 also severely reduced HAI titers of these narrowly focused serum samples (Table 2). In contrast, antibodies in our control serum samples did not have reduced binding to VLPs possessing HAs with substitutions at residues 166 and 167 (Fig. 6D to F) and did not have reduced HAI titers to viruses with these substitutions (Table 2). Antibodies in serum from donors 5 and 6 showed no reduction in binding to VLPs possessing HAs with substitutions that were selected by each autologous serum sample (Fig. 6E and F) and no reductions in HAI titers to these viruses with these mutations. Antibodies from donors 4 and 5 bound less efficiently to HAs possessing substitutions that arose during passage in the presence of donor 4 serum (Fig. 6D); however, these substitutions did not dramatically reduce HAI titers (Table 2). These data indicate that the serum samples that were narrowly focused on the HA epitope involving residue 166 efficiently selected escape mutations at residues 166 and 167 that directly prevented binding of serum polyclonal antibodies, similar to what has been previously reported for monoclonal antibodies. These data also indicate that this experimental setup has the potential to elucidate the specificity of antibodies that are present in moderate concentrations in polyclonal sera, as demonstrated by passaging experiments involving the sample from donor 4.

FIG 6.

Antigenic characterization of HA variants that arose after passaging. ELISAs were completed using VLPs with HAs that had substitutions that arose after passaging in the presence of human sera. Antibody binding between different ELISA plates was normalized by including a standard monoclonal on each plate. A series of eight serum dilutions were tested, and data are expressed as percent binding (based on area under the curve) relative to binding to WT HA. Experiments were completed in triplicate. Means and SD from three different experiments are shown. (*, P < 0.05; Dunnett's multiple-comparison test comparing results for VLPs with WT HA to those for VLPs with variant HAs.)

TABLE 2.

HAI titers using viruses that emerged in passaging experimentsa

| Donor no. | HAI titer by virus |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | K166E | K166N | K166R | S167P | P128L | S146G | S186P | A189T | |

| 1 | 320 | <10 | 20 | 40 | 60 | 160 | 320 | 160 | 240 |

| 2 | 120 | 20 | 20 | 10 | <10 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| 3 | 120 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 120 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| 4 | 120 | 160 | 240 | 160 | 160 | 120 | 120 | 80 | 120 |

| 5 | 80 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 80 | 80 | 160 | 80 |

| 6 | 160 | 160 | 240 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 80 | 160 |

HAI assays were completed using viruses engineered to possess the HA substitutions that arose to the highest frequency for each passage condition. Boldface indicates HAI titers that are decreased >4-fold relative to the HAI titer using virus with WT HA.

DISCUSSION

Information on mechanisms by which influenza viruses evade human antibodies may be useful in understanding influenza virus evolution and forecasting future antigenic drift. In this study, we studied individuals with antibody responses that were focused on a single HA epitope that was conserved in past viral strains. We found that H1N1 viruses rapidly acquired HA mutations when grown in ovo in the presence of these narrowly focused serum samples and that these substitutions directly prevented the binding of serum antibodies from these individuals. Viruses grown in the presence of these serum samples acquired mutations at HA residue 166 or 167. This is notable since these serum samples were collected prior to the 2013-2014 season, during which a mutation at HA residue 166 of H1N1 viruses quickly rose to fixation (11). A similar result using cell culture viral passaging was recently reported using convalescent-phase serum collected in 2009 from an individual in Japan (14). We propose that influenza viruses might evolve in individuals that possess narrowly focused antibody responses by acquiring mutations that directly prevent antibody binding.

In classic studies from the 1940s and 1950s, Thomas Francis, Jr., and colleagues and Davenport et al. demonstrated that influenza virus exposures boost antibody responses to viral strains that humans encounter early in life (5, 15–18). Some humans appear to have highly focused antibody responses against influenza viruses (19), and our laboratory and other investigators have shown that H1N1 antibody responses typically recognize epitopes that are conserved between contemporary viruses and viral strains that were encountered in childhood (11, 20–22). While we have previously shown that many individuals possess H1N1 antibodies that target an HA epitope involving residue 166 (11), it is unknown if other humans possess antibodies that narrowly target other HA antigenic sites or if the majority of humans possess polyclonal responses that include many different antibody specificities. One of our control donors (a donor who did not have HAI antibodies affected by the K166Q HA substitution) selected for viruses with substitutions at HA residues 186 and 193 that directly blocked the binding of a fraction of that donor's antibodies (Fig. 6). This suggests that the egg passaging system described in the manuscript might be potentially useful for identifying previously undefined narrowly focused antibody specificities.

Our study has some limitations. We completed passaging experiments in embryonated chicken eggs, but the sialic acid types that are present in eggs are much different from those in the human airway. The specific amino acid changes that arose experimentally (K166E, K166N, K166R, and S167P) were different from those in variant viruses that arose in humans (K166Q and S167T). A similar observation was made by DeDiego and colleagues in H3N2 passaging experiments (23). These differences in specific amino acid substitutions could be due to differences in each variant's ability to bind to different sialic acid types that are in eggs versus those in human airways. Another limitation of our study is that our mutant VLP panel was extensive but did not exhaustively cover all possible antibody binding sites on HA. It is also possible that our VLP ELISA-based approach is not sensitive enough to detect low levels of certain types of antibodies. Future experiments can use more recent technological advances, such as deep mutational scanning (24, 25), to better define the specificity of serum antibodies prior to passaging experiments.

Despite these limitations, our study is important because it demonstrates that influenza viruses can escape some types of human antibodies by simply acquiring mutations that directly prevent the binding of serum antibodies. It will be important for future studies to clearly define the prevalence of narrowly focused serum antibody responses versus more broadly reactive serum antibody responses within the human population. This information will be useful to understand which antigenic escape mechanisms (direct escape versus increased viral attachment) are preferentially used within humans. A better understanding of influenza virus antibody specificities and antiviral immune escape mechanisms will ultimately improve our ability to predict how influenza viruses might change in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human samples.

Serum samples were previously collected from human participants in the Household Influenza Vaccine Evaluation (HIVE) cohort that was approved by the University of Michigan Medical School institutional review board (26). The University of Pennsylvania institutional review board approved experiments using deidentified serum samples collected at the University of Michigan.

Viruses.

The HA and NA genes of the A/California/07/2009 H1N1 strain were cloned into the vector pHW2000. The A/California/07/2009 HA used in these studies was engineered to possess the D225G mutation that allows the virus to replicate efficiently in eggs without additional egg-adaptive mutations (11). Viruses with A/California/07/2009 HA and NA and A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 internal genes were produced via reverse genetics by transfecting cocultures of 293T and MDCK-SIAT1 cells. Transfection supernatants were collected 3 days after transfection and stored at −80°C. Viruses from transfection supernatants were further amplified in embryonated chicken eggs. We sequenced the HA of our stock viruses and confirmed that HA mutations did not arise during viral propagation in eggs. For some experiments, we used viruses expressing the A/California/07/2009 HA with a K166Q substitution that was introduced using site-directed mutagenesis. For other experiments, we used site-directed mutagenesis and reverse genetics to create viruses expressing the A/California/07/2009 HA with substitutions that arose during our passaging experiments.

Viral passaging in embryonated eggs.

For the first viral passage, we incubated different dilutions of each human serum sample (1:10, 1:40, and 1:160) with 4 × 105 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) of virus in a total volume of 50 μl for 30 min at 23°C. These serum-virus mixtures were injected into day 10 embryonated chicken eggs (1 egg per serum-virus mixture), and allantoic fluid from each egg was collected 3 days later. Viral titers in allantoic fluid were determined by TCID50 using MDCK cells. For the second viral passage, we used virus isolated from the most concentrated amount of serum that did not lead to complete neutralization during the first passage. For example, if we were able to isolate virus from conditions involving 1:160 and 1:40 dilutions of serum but not a 1:10 dilution of serum in the first passage, then we used virus incubated in the first passage in the presence of a 1:40 dilution of serum (i.e., the largest amount of serum without complete neutralization). Using a method similar to that for the first passage, we incubated different dilutions of each human serum sample (1:10, 1:40, and 1:160) with 4 × 105 TCID50 of virus isolated from passage 1 in a total volume of 50 μl for 30 min at 23°C. These serum-virus mixtures were injected into embryonated chicken eggs (1 egg per serum-virus mixture), and allantoic fluid was collected 3 days later. Viral titers in allantoic fluid for the second passage were determined by TCID50 using MDCK cells. We carried out the third passage in the same manner as the second passage.

Sequencing.

Bulk RNA was extracted from allantoic fluid samples using a QIAamp Viral RNA minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Previously described primers were used for full-length amplification of the influenza A virus genome. Reverse transcription was performed using Superscript III First-Strand Reaction Mix (Thermo Fisher) and an equimolar mix of the 5′-Hoffmann-U12-A4 and 5′-Hoffmann-U12-G4 primers, which bind to the conserved U12 region present on each influenza virus gene segment (27). One microliter of annealing buffer and 1 μl of 2 μM primer mix were added to 6 μl of RNA eluent and then incubated at 65°C for 5 min. Ten microliters of 2× First-Strand Reaction Mix and 2 μl of Superscript III/RNaseOUT Enzyme Mix were added on ice for a 20-μl total reaction volume and then incubated at 25°C for 10 min, at 50°C for 50 min, and at 85°C for 5 min. The entire 20-μl volume of the reverse-transcription reaction was used as the template in a 100-μl PCR using KOD HotStart Reaction Mix (EMP Millipore) and a 24-primer cocktail at a total concentration of 600 nM as previously described (28). Thirty-five cycles of PCR amplification were performed with an annealing temperature of 55°C and an extension time of 3 min. An equimolar mix of plasmids containing A/California/07/2009 HA and NA and A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 PB1, PB2, PA, NP, NS, and M was amplified simultaneously to estimate PCR, library preparation, and sequencing errors. DNA was purified with 1× AMPure beads (Beckman Coulter), and libraries were created with an Illumina sequencing Nextera XT kit. Libraries were sequenced on a MiSeq platform (Illumina) with 250-bp paired-end reads. Library preparation and sequencing were performed in triplicate, starting from independent reverse-transcription reactions.

Processing of sequence data.

We removed downstream analysis sequencing files (each representing a technical replicate) that did not have at least 5,000 raw sequencing reads (6 of 96 experimental sample replicates); all samples included in the downstream analysis had at least two technical replicates remaining. Raw sequencing reads were mapped to the influenza virus genome with bwa, using default parameters. The samtools package was used to sort and index alignment files (.bam) and then to convert them to pileup format; they were then used as input for varscan mpileup2cns (–min-coverage 30, –min-var-freq 0.01) to call mutations on individual technical replicates. A custom R script calculated each mutation's amino acid position based on its nucleotide position within each segment.

Quality filtering.

We noticed regions of high apparent mutation at the edges of amplicons, but these were present in controls as well as in experimental sequences. In some cases, these showed clustered substitutions. Some of these corresponded to regions of lower read depth. We hypothesize that the apparent mutations were the result of PCR or sequencing error and not authentic substitutions in viral genomes and so excluded these regions from subsequent analysis. Borders were chosen to exclude these regions of high substitution rates. We removed mutations outside nucleotides 1 to 1,667 for the HA segment, 5 to 1,011 for M, 5 to 1,548 for NP, 5 to 874 for NS1, 5 to 2,217 for PA, 14 to 2,326 for PB1, and 5 to 2,325 for PB2. We did not filter mutations on NA based on position. We then removed mutations that did not appear in at least two technical replicates within each sample. Finally, we removed mutations with an average allele frequency of less than 2.5%, which was the highest average frequency seen in any of the plasmid sequences sampled and thus identified as the maximum minor allele frequency.

All code used in these analyses can be found on GitHub at https://github.com/BushmanLab/fluSera.

HAI assays.

Serum samples were pretreated with receptor-destroying enzyme (RDE) (Denka Seiken), and HAI titrations were performed in 96-well round-bottom plates (BD). Sera were serially diluted 2-fold and added to four agglutinating doses of virus in a total volume of 100 μl. Turkey erythrocytes (Lampire) were added (12.5 μl of a 2% [vol/vol] solution). The erythrocytes were gently mixed with sera and virus, and agglutination was determined after incubation for 60 min at room temperature. HAI titers were expressed as the inverse of the highest dilution that inhibited four agglutinating doses of turkey erythrocytes. Each HAI assay was performed independently on three different dates.

VLPs.

Virus-like particles (VLPs) expressing the A/California/07/09 HA with and without amino acid substitutions were produced. We used HAs that possess a Y98F substitution which prevents HA binding to sialic acid (29). It has previously been shown that Y98F has minimal effects on antigenic structure (30). VLPs with HAs that have the Y98F substitution can be produced in the absence of NA, which is advantageous for studying anti-HA antibodies in polyclonal sera. For VLP production, we transfected 293T cells (90% confluent in T175 flask) with plasmids expressing HIV Gag (36 μg), HAT (human airway trypsin-like protease) (0.54 μg), and each HA (3.6 μg) using polyethylenimine transfection reagent. We isolated culture supernatants and concentrated VLPs using a 20% sucrose cushion. HA amounts in each VLP preparation were determined via ELISAs using the 146-B09 or 065-C05 monoclonal antibody which binds to conserved regions of the H1 head or stalk, respectively (31).

ELISAs.

ELISA plates were coated overnight at 4°C with VLPs. ELISA plates were blocked with a 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 2 h. Plates were washed three times with double-distilled H2O (ddH2O), and serial dilutions of each serum sample were added to plates in 1% BSA in PBS. After 2 h of incubation, plates were washed again, and a peroxidase-conjugated anti-human secondary antibody (product number 109-036-098; Jackson ImmunoResearch) or a peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (MP Biomedicals) diluted in 1% (wt/vol) BSA solution was added. After a 1-h incubation, plates were washed, and a 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (product number 50-00-03; Seracare) was added. HCl was added to stop TMB reactions, and absorbances were measured using a plate reader. One-site specific binding curves were fitted in Prism software. After background subtraction (from ELISA plates that did not have VLPs), serum binding to each VLP relative to that of the vaccine strain was determined using the area under the curve. Equivalent coating of each plate was verified using the 065-C05 or 146-B09 monoclonal antibody (31).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (1R01AI113047, S.E.H.; 1R01AI108686, S.E.H.; 1R01AI097150, A.S.M.; CEIRS HHSN272201400005C, S.E.H. and A.S.M.) and the Centers for Disease Control (U01IP000474, A.S.M.). S.E.H. and J.D.B. hold Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Awards from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

We thank Ian York (CDC) for providing plasmids to express murine monoclonal antibodies that were used to normalize HA amounts for ELISAs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yewdell JW. 2011. Viva la revolucion: rethinking influenza a virus antigenic drift. Curr Opin Virol 1:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodewes R, de Mutsert G, van der Klis FR, Ventresca M, Wilks S, Smith DJ, Koopmans M, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF. 2011. Prevalence of antibodies against seasonal influenza A and B viruses in children in Netherlands. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18:469–476. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00396-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kucharski AJ, Lessler J, Read JM, Zhu H, Jiang CQ, Guan Y, Cummings DA, Riley S. 2015. Estimating the life course of influenza A(H3N2) antibody responses from cross-sectional data. PLoS Biol 13:e1002082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobey S, Hensley SE. 2017. Immune history and influenza virus susceptibility. Curr Opin Virol 22:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francis T. 1960. On the doctrine of original antigenic sin. Proc Am Philos Soc 104:572. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrat F, Flahault A. 2007. Influenza vaccine: the challenge of antigenic drift. Vaccine 25:6852–6862. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caton AJ, Brownlee GG, Yewdell JW, Gerhard W. 1982. The antigenic structure of the influenza virus A/PR/8/34 hemagglutinin (H1 subtype). Cell 31:417–427. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yewdell JW, Caton AJ, Gerhard W. 1986. Selection of influenza A virus adsorptive mutants by growth in the presence of a mixture of monoclonal antihemagglutinin antibodies. J Virol 57:623–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hensley SE, Das SR, Bailey AL, Schmidt LM, Hickman HD, Jayaraman A, Viswanathan K, Raman R, Sasisekharan R, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. 2009. Hemagglutinin receptor binding avidity drives influenza A virus antigenic drift. Science 326:734–736. doi: 10.1126/science.1178258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis AKF, McCormick K, Gumina ME, Petrie JG, Martin ET, Xue KS, Bloom JD, Monto AS, Bushman FD, Hensley SE. 2018. Sera from individuals with narrowly focused influenza virus antibodies rapidly select viral escape mutations in ovo. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/324707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Linderman SL, Chambers BS, Zost SJ, Parkhouse K, Li Y, Herrmann C, Ellebedy AH, Carter DM, Andrews SF, Zheng NY, Huang M, Huang Y, Strauss D, Shaz BH, Hodinka RL, Reyes-Teran G, Ross TM, Wilson PC, Ahmed R, Bloom JD, Hensley SE. 2014. Potential antigenic explanation for atypical H1N1 infections among middle-aged adults during the 2013–2014 influenza season. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:15798–15803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409171111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrie JG, Parkhouse K, Ohmit SE, Malosh RE, Monto AS, Hensley SE. 2016. Antibodies against the current influenza A(H1N1) vaccine strain do not protect some individuals from infection with contemporary circulating influenza A(H1N1) virus strains. J Infect Dis 214:1947–1951. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raymond DD, Bajic G, Ferdman J, Suphaphiphat P, Settembre EC, Moody MA, Schmidt AG, Harrison SC. 2018. Conserved epitope on influenza-virus hemagglutinin head defined by a vaccine-induced antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:168–173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715471115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C, Hatta M, Burke DF, Ping J, Zhang Y, Ozawa M, Taft AS, Das SC, Hanson AP, Song J, Imai M, Wilker PR, Watanabe T, Watanabe S, Ito M, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Russell CA, James SL, Skepner E, Maher EA, Neumann G, Klimov AI, Kelso A, McCauley J, Wang D, Shu Y, Odagiri T, Tashiro M, Xu X, Wentworth DE, Katz JM, Cox NJ, Smith DJ, Kawaoka Y. 2016. Selection of antigenically advanced variants of seasonal influenza viruses. Nat Microbiol 1:16058. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis T., Jr 1955. The current status of the control of influenza. Ann Intern Med 43:534–538. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-43-3-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francis T Jr, Salk JE, Quilligan JJ Jr. 1947. Experience with vaccination against influenza in the spring of 1947: a preliminary report. Am J Public Health 37:1013–1016. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.37.8.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davenport FM, Hennessy AV, Francis T Jr. 1953. Epidemiologic and immunologic significance of age distribution of antibody to antigenic variants of influenza virus. J Exp Med 98:641–656. doi: 10.1084/jem.98.6.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davenport FM, Hennessy AV, Bernstein SH, Harper OF Jr, Klingensmith WH. 1955. Comparative incidence of influenza A-prime in 1953 in completely vaccinated and unvaccinated military groups. Am J Public Health Nations Health 45:1138–1146. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.45.9.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang ML, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 1986. Comparative analyses of the specificities of anti-influenza hemagglutinin antibodies in human sera. J Virol 57:124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Myers JL, Bostick DL, Sullivan CB, Madara J, Linderman SL, Liu Q, Carter DM, Wrammert J, Esposito S, Principi N, Plotkin JB, Ross TM, Ahmed R, Wilson PC, Hensley SE. 2013. Immune history shapes specificity of pandemic H1N1 influenza antibody responses. J Exp Med 210:1493–1500. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wrammert J, Koutsonanos D, Li GM, Edupuganti S, Sui J, Morrissey M, McCausland M, Skountzou I, Hornig M, Lipkin WI, Mehta A, Razavi B, Del Rio C, Zheng NY, Lee JH, Huang M, Ali Z, Kaur K, Andrews S, Amara RR, Wang Y, Das SR, O'Donnell CD, Yewdell JW, Subbarao K, Marasco WA, Mulligan MJ, Compans R, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. 2011. Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J Exp Med 208:181–193. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang KY, Rijal P, Schimanski L, Powell TJ, Lin TY, McCauley JW, Daniels RS, Townsend AR. 2015. Focused antibody response to influenza linked to antigenic drift. J Clin Invest 125:2631–2645. doi: 10.1172/JCI81104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeDiego ML, Anderson CS, Yang H, Holden-Wiltse J, Fitzgerald T, Treanor JJ, Topham DJ. 2016. Directed selection of influenza virus produces antigenic variants that match circulating human virus isolates and escape from vaccine-mediated immune protection. Immunology 148:160–173. doi: 10.1111/imm.12594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doud MB, Hensley SE, Bloom JD. 2017. Complete mapping of viral escape from neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006271. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doud MB, Bloom JD. 2016. Accurate measurement of the effects of all amino-acid mutations on influenza hemagglutinin. Viruses 8:E155. doi: 10.3390/v8060155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohmit SE, Petrie JG, Malosh RE, Johnson E, Truscon R, Aaron B, Martens C, Cheng C, Fry AM, Monto AS. 2016. Substantial influenza vaccine effectiveness in households with children during the 2013-2014 influenza season, when 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus predominated. J Infect Dis 213:1229–1236. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann E, Stech J, Guan Y, Webster RG, Perez DR. 2001. Universal primer set for the full-length amplification of all influenza A viruses. Arch Virol 146:2275–2289. doi: 10.1007/s007050170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue KS, Stevens-Ayers T, Campbell AP, Englund JA, Pergam SA, Boeckh M, Bloom JD. 2017. Parallel evolution of influenza across multiple spatiotemporal scales. Elife 6:e26875. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whittle JR, Wheatley AK, Wu L, Lingwood D, Kanekiyo M, Ma SS, Narpala SR, Yassine HM, Frank GM, Yewdell JW, Ledgerwood JE, Wei CJ, McDermott AB, Graham BS, Koup RA, Nabel GJ. 2014. Flow cytometry reveals that H5N1 vaccination elicits cross-reactive stem-directed antibodies from multiple Ig heavy chain lineages. J Virol 88:4047–4057. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03422-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whittle JR, Zhang R, Khurana S, King LR, Manischewitz J, Golding H, Dormitzer PR, Haynes BF, Walter EB, Moody MA, Kepler TB, Liao HX, Harrison SC. 2011. Broadly neutralizing human antibody that recognizes the receptor-binding pocket of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:14216–14221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111497108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson JR, Guo Z, Tzeng WP, Garten RJ, Xiyan X, Blanchard EG, Blanchfield K, Stevens J, Katz JM, York IA. 2015. Diverse antigenic site targeting of influenza hemagglutinin in the murine antibody recall response to A(H1N1)pdm09 virus. Virology 485:252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]