Abstract

Consumption of energy is a national and international phenomenon that showed increase in market spread and profits from 1990 and made the emergence of many brands. Energy drinks are aggressively marketed with the claim that these products give an energy boost to improve physical and cognitive performance. However, studies supporting these claims are limited. The study examines the new phenomena of energy drinks among university students in Lebanon, based on the participants’ personnel characteristics, university grade and the impact on health status. The study also determined whether high frequency of consumption was correlated with negative physical health symptoms. A cross-sectional study survey was undertaken on students aged between 18 and 30 years in private university over three branches (Beirut, Tripoli and Saida). A self-administered questionnaire was used inquiring about socio-demographic characteristics, consumption patterns and side effect of energy drinks. Data was analyzed using SPSS 24. Findings showed a serious concern exists for the health and safety of the most at risk students who engaged in daily energy drink usage when two-thirds of these reported difficulties sleeping, more than one experienced heart palpitation and blood pressure; one-third had anxiety, nervousness and feeling thirsty, and one fifth indicated tiredness and headache. Such symptoms are reported with excessive consumption of caffeine that had adverse health effect on the body.

Keywords: Health effects, Drink energy, Physical health symptoms

Introduction

Energy drink consumption has become popular and is occurring in large proportions of minors and young adults’. The marketing uses themes of an active lifestyle to attract people to buy them and drag the sport interest people to buy them as increased energy and performance targeted at teenagers, sport persons and university students those who need energy. Most of the review found that students used energy drinks for purpose built on information from their own mind. Although energy has an impact of giving energy to be capable to continue your day, work …etc, but it has a negative impact on your health, the constituents of the energy drinks are: energy drinks contain potentially large doses of caffeine, herbs, and other substances. Nevertheless, there is lack of consumer and scientific knowledge about the risks to health from the mixture of ingredients, the doses, and frequency of consumption. Key substances found in typical energy drinks include: (a) large levels of caffeine; (b) herbal ingredients like ginseng, (fungi), milk thistle, and Echinacea; (c) amino acids consisting of taurine, glutamine, and carnitine; (d) vitamins b3, b6, and b8; (d) artificial sweeteners or unhealthy sugar derived from corn syrup and salt. Many of these substances have other uses in medicine as part of treatments for certain conditions. Many ingredients found in energy drinks have warnings associated with them with respect to known and unknown toxicity and physical symptoms (e.g., potential hypersensitivity and allergic reactions, impact on blood sugar and insulin insensitivity, digestive disorders, blood pressure and cardiovascular risks, nervous system effects, and influence on behavior) and many of these substances have medically proven contraindications with certain prescription medications.

With regards to caffeine, the concentration will vary by brand. The amount of caffeine in a typical energy drink ranges from an 8-ounce cup of brewed coffee or a 1 once espresso drink up to a concentrated mega dose of 500 mgs of caffeine per drink. Nevertheless, some plant extracts are stimulants and may not be part of the estimates of the caffeine dosage on the product label. For example, the herbal stimulant known as “Guarana” and others were reported as being a source of caffeine not always included in the count on labels resulting in higher dosages of caffeine than reported. Energy drinks with high doses of caffeine and other stimulants pose a risk to health. Caffeine is a diuretic and stimulant and in large concentrations can place a person engaged in moderate activity at risk for experiencing dehydration.

Aim of this study is to assess the use of energy drink consumption among university students in Lebanon and the negative impact on their health, and the effect of gpa consumption. The paper is organized as follows; “Review of literature” section summarize the literature review, methodology is described in “Methodology” section, “Study results” section provides the result of the study, and discussion and conclusion are given in “Discussion” and “Conclusion” sections.

Review of literature

Relying on a European Food Safety study in 2011, research found that 70% of minors and 30% of adults consumed energy drinks in 16 European countries examined [1]. In Western Saudi Arabia, 55% of secondary schoolgirls drank energy drinks. Similarly, research found that 54% of college males in Eastern Saudi Arabia regularly consumed energy drinks [2]. A study in the University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) found that 41% of University students regularly drank energy drinks [3]. Another study of 125 medical students in Ajman, UAE found that 92% recently drank energy drinks [4]. Research in Saudi Arabia found high caffeine and herbal stimulant consumption associated with increased blood pressure, dehydration, type 2 diabetes symptoms, nervousness, and abdominal pain [5].

Methodology

A cross-sectional design used and administered electronic survey to a random sample of 100 Lebanese males and females among three higher education campuses (Beirut, Sayda, Tripoli campuses) in Lebanon; Demographic and descriptive data were collected to help analyze survey measures. The study implicit the null hypotheses that no statistically significant relationships or differences (at or below the alpha level of .05) would be found based on gender, age, and year in university program and for statistical results pertaining to level of energy drink use, quality of health, and negative physical health symptoms or effects.

Basic questionnaire was developed and pilot-tested based on need to measure self reported prevalence of energy drink use, the type of energy drinks consumed, and self-reported effects on health. Survey exclude questions about coffee or tea because energy drinks found in local stores with high levels of caffeine, sugar content, herbal ingredients, and other substances.

The total population of Lebanese students attending among the three different campuses in program years 1–3 and above was 3300. Hence, one-third of these were randomly selected. For example, from 1100 surveys administered, 100 were completed, which yielded a ± 3.1% margin of error based on the 95% level of confidence. From these, about 25% reported never using energy drinks; therefore, survey responses were obtained and reported for only 75 who recorded low to high consumption of energy drinks.

The statistics used were fit for the type of data, level of measurements, and study purpose. Survey results were analyzed in IBM-SPSS software version 23 [6]. Tables reported the frequency and percentage of participants with demographic characteristics and how often they consumed energy drinks. Cross-tabulation tables and Chi square determined if there were any statistically significant proportional differences in consumption based on gender, university program year, and age. Chi square (for categorical variables) determined if there were any meaningful associations between level of consumption and quality of health.

The proportion of respondents with different reasons for using energy drinks and their brand preferences were summarized by graphs. Any statistically significant mean differences in Grade Point Average (GPA) existed between “low to no users” (e.g., no use to a few times a month) and those that consumed “one or more” energy drinks per day were determined by independent sample t-tests. This is a useful inferential procedure for comparing means of a dependent variable between two groups. In this study, no statistical assumptions were violated relative to the equality variances between the groups and the normal distribution of the dependent variables. Moreover, spearman correlations examined whether drinking 1 to 3 or more energy drinks a day was statistically correlated with negative adverse health effects or symptoms, such as overall quality of health, feeling nervous, increased blood pressure, heart palpitations, headaches, blurred vision, feeling thirsty, feeling tired, and/or experiencing sleeping difficulties.

Study results

The energy drink survey was completed by 100 participants. Out of these 100, per Table 1, Female Lebanese higher education were 39%, 45% were of age 18–20 years, 55% were in academic year 2 program, and 33% had an overall health of good to excellent.

Table 1.

participant characteristics

| Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Valid | ||||

| Male | 61 | 61 | 61 | 61 |

| Female | 39 | 39 | 39 | 100 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Age | ||||

| Valid | ||||

| 18–20 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| 21–22 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 86 |

| 23+ | 14 | 14 | 14 | 100 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Year | ||||

| Valid | ||||

| Year 1 and 2 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Year 3 and above | 55 | 55 | 55 | 100 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Region | ||||

| Valid | ||||

| Beirut | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| Sayda | 30 | 30 | 30 | 65 |

| Tripoli | 35 | 35 | 35 | 100 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Heath | ||||

| Valid | ||||

| Poor to very poor | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Average health | 56 | 56 | 56 | 67 |

| Good to excellent health | 33 | 33 | 33 | 100 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

Table 2 results shows that out of 100 students, 23% or 23 students’ never drunk energy drinks. Hence, 77% drank energy drinks with variable patterns. Students who drank energy drinks 1 to times a week had the largest proportion of 27% when examining the 77 who consumed energy drinks, data shows that 19% drank 1 to 3+ a day.

Table 2.

How often energy drink consumed

| Energy drink consumption | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent | |

| Valid | ||||

| Never | 23 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 23.0 |

| 1–2 times a month | 27 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 50.0 |

| 1–2 times a week | 20 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 70.0 |

| 3–4 times a week | 11 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 81.0 |

| Once a day | 10 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 91.0 |

| Two energy drinks a day | 8 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 99.0 |

| Three or more drinks a day | 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 100.0 |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

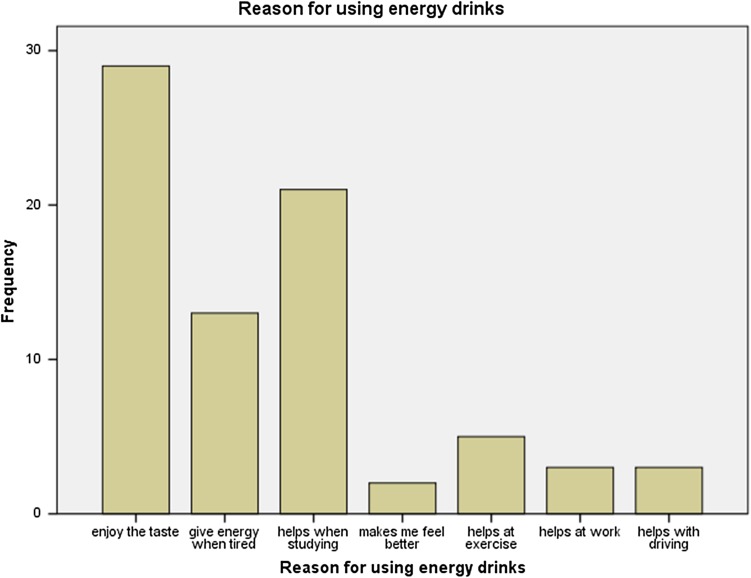

The data in Fig. 1 shows that among the 77 students who drink energy drink. 29% indicated that the reason for using it is enjoying the taste and 21% reported it has helped them to study. Moreover, 13% reported it as source of energy. Moreover, 2% indicated it helped them feel better, and 11% reported it helped them exercise, work, and drive. A large proportion of low energy drink users did so to make them feel better and for enjoying the taste the taste. The 29 students who said that they enjoy the taste most of them drinks once and more per day. Therefore, the students reporting needing energy drinks while enjoying the taste had greater frequency of consumption.

Fig. 1.

Reason for using energy drinks

Figure 2 indicates the proportion of students out of 100 reporting an energy drink brand preference. Red Bull was reported by 35 students or 35% as most preferred. Boom-Boom was reported by 20 students or 20%, XXL was reported by 10 students. Other, reported 10% preferring other brands, such as AMP (9%) and power horse (1%) (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Preference brand of energy drink

Table 3.

Drinks 1 or more a day

| Variable | 1–4 a week | 1–3 a day | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| All male | n = 3 | n = 14 | n = 46 |

| 69.60% | 30.40% | 100% | |

| All female | n = 26 | n = 5 | n = 31 |

| 83.90% | 16.10% | 100% | |

| Year 1 and 2 male | n = 16 | n = 5 | n = 21 |

| 76.20% | 23.80% | 100% | |

| Year 1 and 2 female | n = 13 | n = 3 | n = 16 |

| 81.25% | 18.75% | 100% | |

| Year 3 and above male | n = 16 | n = 9 | n = 25 |

| 64% | 36% | 100% | |

| Year 3 and above female | n = 13 | n = 2 | n = 15 |

| 86.60% | 13.40% | 100% | |

| 18–20 male | n = 14 | n = 5 | n = 19 |

| 73.70% | 26.30% | 100% | |

| 18–20 female | n = 14 | n = 3 | n = 17 |

| 82.40% | 17.60% | 100% | |

| 21–22 male | n = 12 | n = 9 | n = 21 |

| 57.20% | 42.80% | 100% | |

| 21–22 female | n = 8 | n = 1 | n = 9 |

| 88.90% | 11.10% | 100% | |

| 23+ male | n = 6 | n = 0 | n = 6 |

| 100% | 0% | 100% | |

| 23+ female | n = 4 | n = 1 | n = 5 |

| 80% | 20% | 100% |

Independent sample t tests compared mean cumulative GPA in university and level of energy drink consumption. Findings in Table 4 indicate that those consuming 1 to 3+ energy drinks a day had a lower GPA (M = 2.479) than students that had “no to low” use (M = 2.762), and this result is statistically significant, t = 1.992, P = 0.0291. Appropriate for two groups with different sample showed a “slight to moderate” GPA difference. No statistically significant GPA differences were found for high levels of energy drink consumption (e.g., 1 to 3+ a day) by gender, t = 2.11, P = 0.4727; and year in university program, t = 2.11, P = 0.4936. So those with higher overall frequency of energy drink consumption, regardless of gender and amount of time attending the university, had lower GPAs than students with “no to low” energy drink use.

Table 4.

Drink 1+ energy drink a day by GPA

| Group | N | M | SD | T | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1+a day | 58 | 2.762 | 0.5167 | 1.992 | 0.029 |

| Low to no use | 19 | 2.479 | 0.3457 | ||

| 1+a day male | 14 | 2.514 | 0.3483 | 2.11 | 0.4727 |

| 1+a day female | 5 | 2.38 | 0.356 | ||

| 1+a day year 1 2 | 8 | 2.413 | 0.3137 | 2.11 | 0.4936 |

| 1+a day year 3 4 | 11 | 2.527 | 0.3744 |

5 point scale (0 = Very Poor, 1 = Poor, 2 = Average, 3 = Good, and 4 = Excellent) examined the self-reported health. The scale was recorded to facilitate Chi squared analysis as follows: 0 = (Very Poor + Poor + Average) and 1 = (Good + Excellent). For males with low to no energy drink use 31.25% reported “good to excellent” health; but males who drank 1 to 3+ energy drinks a day, only 14.3% reported “good to excellent” health (Table 5).

Table 5.

Level of consumption by overall health

| Variable | Low to none | 1–3 a day | Total | x2 | p | phi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male very poor | n = 22 | n = 12 | n = 34 | 1.45 | 0.228 | 0.178 |

| 68.70% | 85.70% | 73.90% | ||||

| Male good to excellent | n = 10 | n = 2 | n = 12 | |||

| 31.25% | 14.30% | 26.10% | ||||

| Female very poor | n = 16 | n = 4 | n = 20 | 0.62 | 0.4294 | 0.142 |

| 61.50% | 80% | 64.50% | ||||

| Female good to excellent | n = 10 | n = 1 | n = 11 | |||

| 38.50% | 20% | 35.50% | ||||

| Overall very poor | n = 38 | n = 16 | n = 54 | 2.39 | 0.1223 | 0.176 |

| 65.50% | 84.20% | 70.10% | ||||

| Overall good to excellent | n = 20 | n = 3 | n = 23 | |||

| 34.50% | 15.80% | 29.90% |

Spearman correlation examined to determine if drinking 1 to 3+ energy drinks a day was with certain types of negative health impacts; relating it directly to energy drink consumption. The statistically significant correlations identified was as following in Table 6 results indicate that students that drank 1 to 3+ energy drinks a day were more likely to have a “slightly” lower overall health self (P = .821, r = − .56) and “slightly” more likely to experience nervousness, (P = .025, r = − 5.06). Students that experienced heart palpitation also had statistically significant correlations with increased blood pressure (P = .010, r = − .578).

Table 6.

Drinks 1 to 3+ a day and health impact

| Health | Feeling nervous health impact (1 to 3+ a day) | Up blood pressure health impact (1 to 3+ a day) | Heart Palpitation health impact (1 to 3+ a day) | Energy drink consumption | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | |||||

| Pearson correlation | 1 | .146 | .091 | − .406 | − .056 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .552 | .711 | .085 | .821 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Feeling nervous health impact (1 to 3+ a day) | |||||

| Pearson correlation | .146 | 1 | − .506* | .069 | − .058 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .552 | .027 | .779 | .814 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Feeling nervous health impact (1 to 3+ a day) | |||||

| Pearson correlation | .091 | − .506* | 1 | − .578** | − .047 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .711 | .027 | .010 | .850 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Heart palpitation health impact (1 to 3+ a day) | |||||

| Pearson correlation | − .406 | .069 | − .578** | 1 | .047 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .085 | .779 | .010 | .850 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Energy drink consumption | |||||

| Pearson correlation | − .056 | − .058 | − .047 | .047 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .821 | .814 | .850 | .850 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Table 7 shows additional statistically significant correlations which indicates that students that drank 1 to 3+ energy drinks a day were more likely to experience headaches (P = .426, r = − .194), blurred vision (P = .618, r = − .102), and experience difficulties sleeping (P = .200, r = − .307). Experiencing energy drink induced sleeping difficulty was correlated with experiencing thirsty feeling (P = .004, r = − .630).

Table 7.

Additional spearman correlation

| Energy drink consumption | Headache additional impact | Blurred vision additional impact | Feeling thirsty additional impact | Tired later additional impact | Sleeping difficulty additional impact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy drink consumption | ||||||

| Pearson correlation | 1 | − 0.194 | − 0.102 | 0.327 | 0.240 | − 0.307 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.426 | 0.678 | 0.171 | 0.323 | 0.200 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Headache additional impact | ||||||

| Pearson correlation | − 0.194 | 1 | 0.130 | − 0.309 | 0.050 | − 0.286 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.426 | 0.595 | 0.199 | 0.839 | 0.236 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Blurred vision additional impact | ||||||

| Pearson correlation | − 0.102 | 0.130 | 1 | − 0.259 | − 0.224 | 0.411 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.678 | 0.595 | 0.285 | 0.357 | 0.081 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Feeling thirsty additional impact | ||||||

| Pearson correlation | − 0.327 | − 0.309 | − 0.259 | 1 | − 0.015 | − .630** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.171 | 0.199 | 0.285 | 0.950 | 0.004 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Tired later additional impact | ||||||

| Pearson correlation | 0.240 | 0.050 | − 0.224 | − 0.015 | 1 | − 0.286 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.323 | 0.839 | 0.357 | 0.950 | 0.236 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Sleeping difficulty additional impact | ||||||

| Pearson correlation | − 0.307 | − 0.286 | 0.411 | − .630** | − 0.286 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.200 | 0.236 | 0.081 | 0.004 | 0.236 | |

| N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

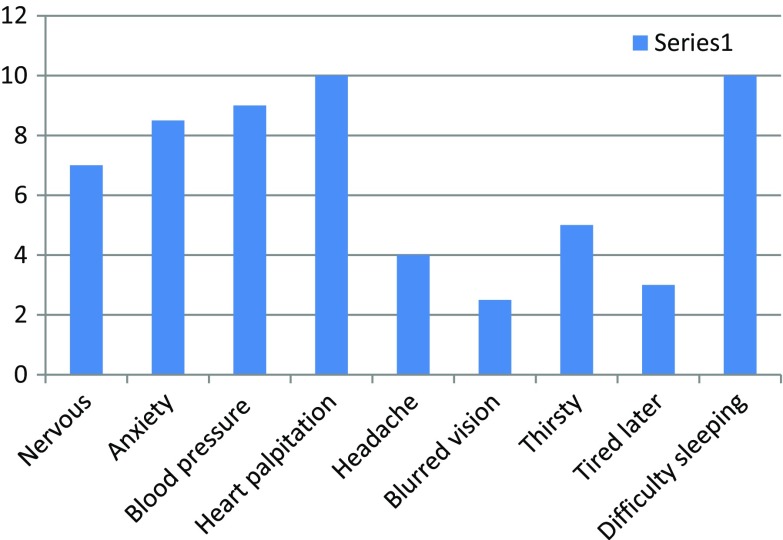

Figure 3, by analyzing the proportion of students who were at risk and more likely to experience adverse health effect from drinking 1 to 3+ energy drinks a day. Problems of sleeping difficulty, blood pressure and heart palpitation were the highest proportion of the students with high daily intake of energy drinks.

Fig. 3.

Drinks 1 to 3+ energy drinks a day

Discussion

A cross-sectional design has been examined energy drink consumption patterns, Energy Drink Survey, and a random sample of a private university in Lebanon across 3 campuses in the Lebanon. Findings provided insight into energy drink consumption levels and associated adverse health symptoms or impacts. The research has found that 77% of the sample reported consuming energy drinks; from 1 to 2 times a month up to 3 or more drinks daily. Males have showed greater proportion than females as more frequent consumers of these drinks. In fact, males were found with the greatest levels of consumption based on age and year attending the university. The brand most frequently preferred by the sample of students was Red Bull followed by Boom-Boom, AMP, and power horse. 19% of the females and males have been identified as being most at risk for the potential harm from energy drinks since they were found to consume 1–3 or more energy drinks a day. A serious concern exists for the health and safety of the most at risk students who engaged in daily energy drink usage when two-thirds of these reported difficulties sleeping, more than one experienced heart palpitation and blood pressure; one-third had anxiety, nervousness and feeling thirsty, and one fifth indicated tiredness and headache. Such symptoms are reported with excessive consumption of caffeine that had adverse health effect on the body.

Conclusion

The conclusions about adverse health impacts from energy drinks are preliminary because across-sectional design was used with correlation data. This was the most appropriate design based on the ethics approval obtained from the institution and based on the objectives for deriving information that could be used for practical purposes by the institution relative to enhancing policies and student support services.

And finally, the health consequences of energy drinks and the differing levels and duration of consumption have not been well researched and reported on in the health science literature. Energy drink contents have not been adequately tested by many food and drug administration’s throughout most of the countries where energy drinks are sold. The safety and risks have not been well researched related to doses of herbal stimulants mixed with caffeine, sweeteners, amino acids, and b-vitamins; especially the contraindications with a range of medications, other products, and the long-term impact on health and disease. More scientific research studies are needed in the future to determine how energy drinks may influence young adults differently based on participant characteristics and substances hypothesized to be problematic to health found in typical energy drinks in the region.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Visram S, Cheetham M, Riby DM, Crossley SJ, Lake AA. Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: a rapid review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes. BMJ Open. 2016;6(10):e010380. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsunni AA. Energy drink consumption: beneficial and adverse health effects. Int J Health Sci. 2015;9(4):468–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robby M, Sanad S. Survey of energy drink consumption and adverse health effects: a sample of university students in the United Arab Emirates. J Sci Res Rep. 2017;15(4):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alhyas L, El Kashef A, AlGhaferi H. Energy drinks in the Gulf Cooperation Council states: a review. JRSM Open. 2016;7(1):2054270415593717. doi: 10.1177/2054270415593717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bawazeer NA, AlSobahi NA. Prevalence and side effects of energy drink consumption among medical students at Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia. IJMS. 2013;1(3):104–108. [Google Scholar]

- 6.George D, Mallery P. IBM SPSS statistics 23 step by step. New York: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]