Bacterial biofilms promote attachment to a variety of surfaces and protect the constituent bacteria from environmental stresses, including antimicrobials. Understanding the mechanisms by which biofilms form will promote our ability to resolve them when they occur in the context of an infection. In this study, we found that Vibrio fischeri tightly controls biofilm formation using three negative regulators; the presence of a single one of these regulators was sufficient to prevent full biofilm development, while disruption of all three permitted robust biofilm formation. This work increases our understanding of the functions of specific regulators and demonstrates the substantial negative control that one benign microbe exerts over biofilm formation, potentially to ensure that it occurs only under the appropriate conditions.

KEYWORDS: Vibrio fischeri, binK, biofilm, response regulator, sensor kinase, syp, two-component regulatory systems

ABSTRACT

Biofilms, complex communities of microorganisms surrounded by a self-produced matrix, facilitate attachment and provide protection to bacteria. A natural model used to study biofilm formation is the symbiosis between Vibrio fischeri and its host, the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes. Host-relevant biofilm formation is a tightly regulated process and is observed in vitro only with strains that have been genetically manipulated to overexpress or disrupt specific regulators, primarily two-component signaling (TCS) regulators. These regulators control biofilm formation by dictating the production of the symbiosis polysaccharide (Syp-PS), the major component of the biofilm matrix. Control occurs both at and below the level of transcription of the syp genes, which are responsible for Syp-PS production. Here, we probed the roles of the two known negative regulators of biofilm formation, BinK and SypE, by generating double mutants. We also mapped and evaluated a point mutation using natural transformation and linkage analysis. We examined traditional biofilm formation phenotypes and established a new assay for evaluating the start of biofilm formation in the form of microscopic aggregates in shaking liquid cultures, in the absence of the known biofilm-inducing signal calcium. We found that wrinkled colony formation is negatively controlled not only by BinK and SypE but also by SypF. SypF is both required for and inhibitory to biofilm formation. Together, these data reveal that these three regulators are sufficient to prevent wild-type V. fischeri from forming biofilms under these conditions.

IMPORTANCE Bacterial biofilms promote attachment to a variety of surfaces and protect the constituent bacteria from environmental stresses, including antimicrobials. Understanding the mechanisms by which biofilms form will promote our ability to resolve them when they occur in the context of an infection. In this study, we found that Vibrio fischeri tightly controls biofilm formation using three negative regulators; the presence of a single one of these regulators was sufficient to prevent full biofilm development, while disruption of all three permitted robust biofilm formation. This work increases our understanding of the functions of specific regulators and demonstrates the substantial negative control that one benign microbe exerts over biofilm formation, potentially to ensure that it occurs only under the appropriate conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Biofilms are complex communities of microorganisms encased in a self-produced matrix that provides protection and permits attachment (1–4). One natural model used to study biofilm formation is the symbiosis between Vibrio fischeri and its host, the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes (5–8). V. fischeri colonizes its host by first forming a biofilm on the surface of the symbiotic organ and then dispersing from the biofilm to enter and colonize the organ (8, 9). Biofilm formation can be observed in laboratory settings by the formation of cohesive wrinkled colonies on solid agar, pellicles at the air-liquid interface in liquid culture under static conditions, and cell clumping in liquid culture under shaking conditions (“shaking cell clumping”) (10–12). In contrast to the biofilms that form naturally on the host, the indicated in vitro biofilms are formed only by strains that have been genetically manipulated (e.g., by overexpression of positive biofilm regulators and/or disruption of negative regulators). These data suggest that biofilm formation is tightly controlled in V. fischeri. At present, seven regulators are known to control biofilm formation. Six of these regulators fall into a large class of regulators known as two-component signaling (TCS) regulators, while the activity of the last regulator remains unknown (Fig. 1).

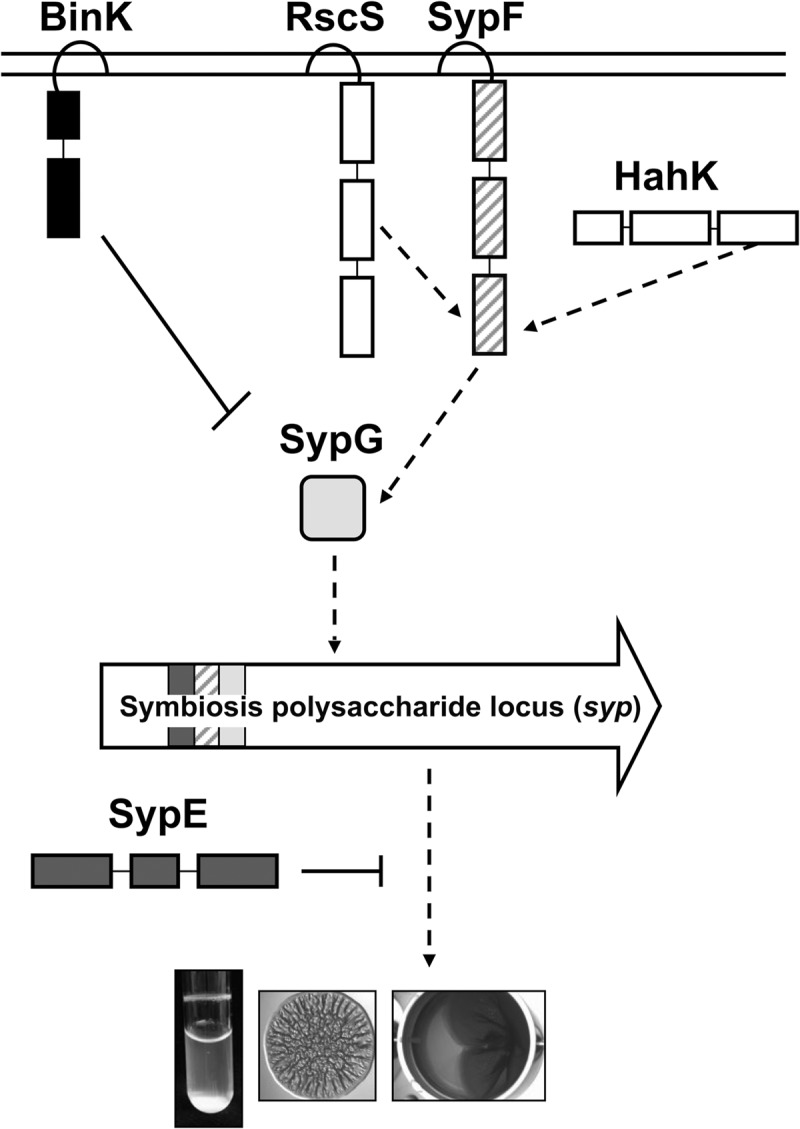

FIG 1.

Model of regulation of biofilm formation by V. fischeri. In V. fischeri, TCS positively and negatively controls biofilm formation by dictating the production of the symbiosis polysaccharide (Syp-PS), the major component of the biofilm matrix. Upon signal activation, RscS initiates a phosphorelay that drives the activation of SypG via SypF's Hpt domain, resulting in increased syp transcription and biofilm formation. Recent work demonstrated that HahK also appears to function upstream of the Hpt domain of SypF to promote biofilm formation (11). Two negative regulators, BinK and SypE, also control biofilm formation. The hybrid SK BinK functions as a strong negative regulator of syp transcription and biofilm formation (11, 26, 27). SypE inhibits biofilm at a level below transcription via controlling the phosphorylation state of SypA (not shown), whose activity remains unknown (24, 29).

TCS connects an external signal to a relevant bacterial output using sensor kinases (SKs) that detect the signal and response regulators (RRs) that elicit the response (13). In the simplest pathway, upon signal receipt, the SK autophosphorylates a conserved histidine residue in its HisKA domain. The phosphoryl group is donated to a conserved aspartate residue within the receiver (REC) domain of a partner RR, which then carries out a response, such as binding DNA or altering enzyme activity (14). More complicated pathways exist wherein sequential phosphotransfer events occur on four highly conserved histidine and aspartate residues present in two or more proteins (15). SKs that contain two or more of these four domains are known as hybrid SKs. Extra steps in a phosphorelay are thought to provide opportunities for the cell to exert additional control over the signaling (16–18). Finally, SKs typically have phosphatase activity, permitting them to exert negative control over their cognate RRs (19).

In V. fischeri, TCS positively and negatively controls biofilm formation by dictating the production of the symbiosis polysaccharide (Syp-PS), the major component of the biofilm matrix (Fig. 1). Control occurs both at the level of transcription of the 18-gene syp locus and at an unknown level below syp transcription (8, 12, 20). Mutants defective for TCS regulators exhibit defective or accelerated biofilm formation in culture and, correspondingly, achieve worse or better colonization outcomes during symbiotic colonization (12, 21, 22).

Until recently, investigations of syp-dependent biofilm formation relied on the overproduction of positive regulators, such as the overexpression of the hybrid SK RscS or the RR SypG. RscS overexpression induces robust biofilm formation, including wrinkled colonies and pellicles (12), as does the overexpression of SypG in a background that lacks the RR SypE (23, 24). These results led to the model that RscS activates SypG, which directly induces syp transcription, and inactivates the inhibitory activity of SypE, culminating in biofilm formation (Fig. 1). In an atypical TCS mechanism, however, the activity of RscS also requires the Hpt domain of SypF, a second hybrid SK with a domain architecture similar to that of RscS (21). Furthermore, another hybrid SK, HahK, appears to similarly feed into the Hpt domain of SypF (11). The absolute requirement for SypF-Hpt in RscS- and HahK-induced biofilm formation brings the total number of known positive regulators to four: RscS, SypG, HahK, and SypF. However, although SypF is considered a positive regulator, the overexpression of wild-type SypF fails to promote biofilm formation; instead, biofilm induction occurs upon the overexpression of SypF1, a variant with increased activity due to a substitution at S247, which is near the putative site of autophosphorylation (H250) (21).

In addition to these four positive regulators, two negative regulators have been identified, SypE and BinK (Fig. 1). Single-copy expression of the RR SypE is sufficient to prevent V. fischeri from producing wrinkled colonies when the transcription factor SypG is overexpressed, despite the substantial induction of syp transcription that occurs under these conditions (24, 25). The hybrid SK BinK functions as a strong negative regulator of syp transcription and biofilm formation (11, 26, 27). binK mutants fail to form biofilms under standard laboratory conditions (without the overexpression of a positive regulator). However, recent work revealed that biofilm formation by the binK mutant can be induced by the addition of calcium chloride at amounts similar to those found in seawater (28). Specifically, calcium induced the binK mutant to produce three in vitro biofilm phenotypes: wrinkled colonies, pellicles, and shaking cell clumping (11). In contrast, calcium supplementation is not required when rscS is overexpressed: the overexpression of rscS is sufficient to induce wrinkled colonies and pellicles (but not shaking cell clumping), even in the absence of calcium. These findings, showing that the loss of BinK does not fully phenocopy RscS overexpression, indicate that other factors are likely involved in negatively controlling biofilm formation in the absence of calcium.

Here, we probed the roles of the two known negative regulators of biofilm formation, BinK and SypE, by generating double mutants and evaluating biofilm formation in the absence of the biofilm-inducing signal calcium. We found that under these conditions, biofilms are negatively controlled not only by BinK and SypE but also by SypF, a known positive regulator. The loss of BinK and SypE, concomitant with a disruption of the inhibitory activity of SypF, permitted V. fischeri to form biofilms in the absence of the calcium signal. Together, these data demonstrate that SypF is active as a biofilm inhibitor under standard laboratory conditions and reveal that three regulators prevent biofilm formation by wild-type V. fischeri.

RESULTS

Identification of a mutant that forms biofilms in the absence of calcium supplementation.

V. fischeri encodes two known negative regulators of biofilm formation, the SK BinK (26, 27) and the RR SypE (24, 25, 29). Although some genetically modified strains of V. fischeri (e.g., RscS-overexpressing strains [12]) form wrinkled colonies on Luria-Bertani salt (LBS) medium, the standard rich medium used to grow this organism, mutation of neither binK nor sypE alone permits wrinkled colony formation. We therefore hypothesized that disruption of both negative regulators may be necessary to permit wrinkled colony formation.

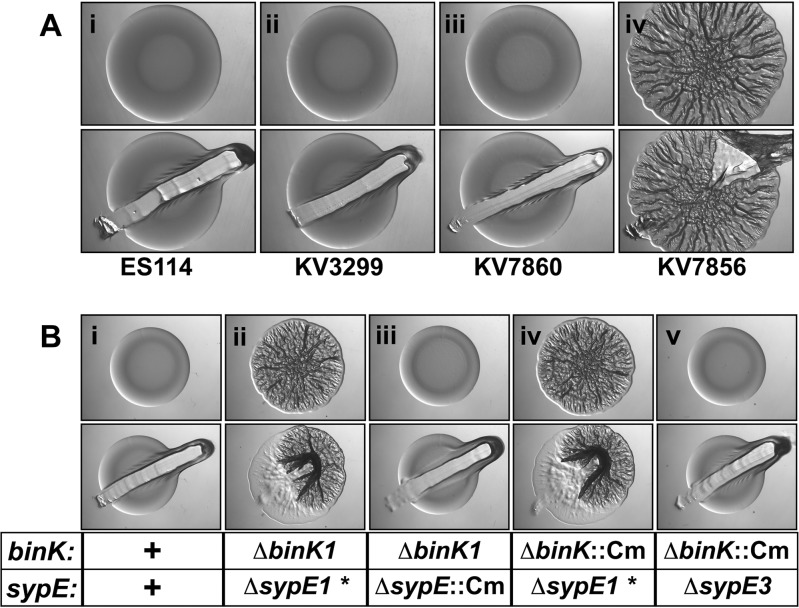

To test this hypothesis, we deleted binK from strain KV3299, a ΔsypE mutant that has been extensively investigated (24, 25, 29), to generate KV7856. Like wild-type strain ES114 (Fig. 2Ai), and as reported previously, the ΔsypE mutant formed smooth colonies under these conditions (24, 25, 29) (Fig. 2Aii). Similarly, a strain in which binK alone is deleted (ΔbinK) formed smooth colonies on LBS medium, as previously reported (11, 26) (Fig. 2Aiii). In contrast, KV7856, defective for the two known negative regulators, produced wrinkled colonies (Fig. 2Aiv). These data initially suggested that BinK and SypE together inhibit biofilm formation.

FIG 2.

Identification of a mutant that forms wrinkled colonies. (A) Production of wrinkled colonies by the following strains was assessed: the wild type (ES114) (i), ΔsypE * (KV3299) (ii), ΔbinK (KV7860) (iii), and ΔbinK ΔsypE * (KV7856) (iv). Colonies were disrupted to evaluate Syp-PS production. (B) Development of wrinkled colony morphology by three new ΔbinK ΔsypE mutants was assessed at 48 h. The specific binK and sypE alleles are shown on the bottom along with the hypothesized presence of a putative point mutation (indicated by *), while the corresponding images are shown on the top, for the following strains: the wild type (ES114) (i), ΔbinK1 ΔsypE1 * (KV7856) (ii), ΔbinK1 ΔsypE::FRT-Cm (KV8391) (iii), ΔbinK::FRT-Cm ΔsypE1 * (KV8389) (iv), and ΔbinK::FRT-Cm ΔsypE3 (KV8390) (v). Colonies were disrupted at 48 h to evaluate Syp-PS production.

However, further experimentation indicated that this conclusion was only partially correct: an independently constructed binK sypE mutant (ΔbinK1 ΔsypE::Cm [where “Cm” represents chloramphenicol]) failed to produce robust wrinkled colonies when grown under the same conditions (Fig. 2Biii) and was, in fact, smooth like the wild-type strain (Fig. 2Bi). To determine the underlying cause of the differing phenotypes, we constructed two additional ΔbinK ΔsypE mutants by introducing a marked binK deletion (ΔbinK::Cm) into two ΔsypE deletion mutants, both the original strain KV3299 (ΔsypE1) and one that had a distinct derivation (ΔsypE3). The former mutant produced wrinkled colonies, similar to the original double mutant (compare Fig. 2Bii and iv), while the latter produced smooth colonies (Fig. 2Bv). Together, these results suggested that disrupting both binK and sypE was insufficient to generate the wrinkled colony phenotype. As a result, it seemed likely that there was a secondary mutation (indicated by an asterisk) in KV3299, the ΔsypE strain used to generate the original double mutant.

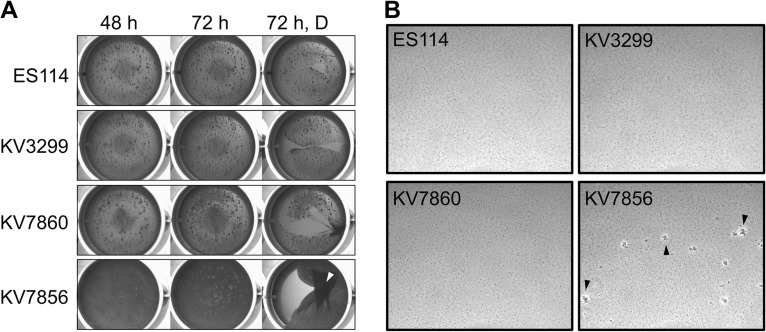

To better understand the biofilm-forming capabilities of ΔbinK ΔsypE * mutant strain KV7856, we asked if it similarly exhibited enhanced phenotypes in other biofilm assays, namely, pellicles and shaking cell clumping. Consistent with the observed wrinkled colony phenotypes, KV7856, but not the ΔsypE * or ΔbinK mutants, was competent to form pellicles that developed by 48 h of incubation and were clearly robust within 72 h, as can be observed by the cohesive nature of the pellicle when disrupted (Fig. 3A). In contrast, KV7856 did not differ from the ΔbinK strain with respect to the shaking cell clumping phenotype: neither strain produced cell clumps when grown with shaking in the absence of calcium, while both strains were competent to do so upon calcium supplementation (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We conclude that additional control mechanisms must be in place to prevent cells from forming large cohesive clumps under shaking conditions in the absence of calcium, and the presence of calcium overrides both this control and negative regulation by SypE and the unknown factor. However, given the other enhanced biofilm phenotypes of KV7856, we revisited the possibility that this strain might exhibit some increase in its capacity to form biofilms when grown without calcium under shaking conditions. We evaluated this possibility using a light microscope to visualize potential biofilm behavior under these conditions. We observed that KV7856, but not the ΔbinK strain, was able to form microscopic aggregates in the absence of calcium supplementation (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, following overnight growth with shaking, standing cultures of KV7856, but not the controls, became viscous and difficult to pipette (data not shown). Thus, ΔbinK ΔsypE * strain KV7856 produced enhanced biofilms under all tested conditions in the absence of calcium albeit only modestly when grown with shaking.

FIG 3.

Biofilm formation by the ΔbinK ΔsypE * mutant. (A) Strains were cultured to log phase, standardized in 2 ml LBS medium in a 24-well microtiter plate, and incubated at 24°C. Development of pellicles by the following strains was assessed at the indicated times: the wild type (ES114), ΔsypE * (KV3299), ΔbinK (KV7860), and ΔbinK ΔsypE * (KV7856). At the end of the time course, the pellicles were disrupted with a toothpick to evaluate pellicle strength (72 h, D). Robust pellicle formation is indicated by the white arrow. (B) Microscopic images of aggregates formed in LBS medium without supplemental calcium. Representative images of the following strains were captured at 18 h postinoculation: wild-type ES114, ΔbinK (KV7860), ΔsypE * (KV3299), and ΔbinK ΔsypE * (KV7856). Aggregates are indicated by the black arrows.

Identification of a mutation in sypF.

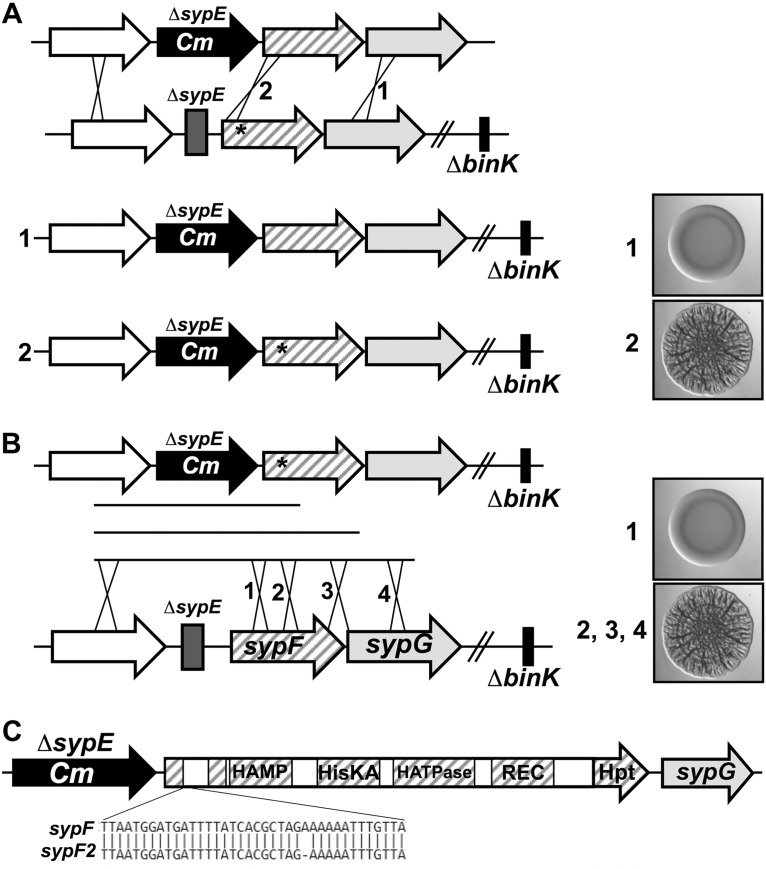

We next sought to determine the location of the unmarked mutation. We hypothesized that it could be within the large syp locus. If so, then it should be possible to observe linkage between the secondary mutation and a representative gene such as sypE. Therefore, we introduced chromosomal DNA containing ΔsypE::Cm and flanking sequences into the wrinkling-competent strain (ΔbinK ΔsypE *) and selected for Cmr (Fig. 4A). We expected that if the point mutation were linked to sypE, then the incoming sequences would repair the mutation, causing the colonies to become smooth. Indeed, most of the resulting Cmr colonies were smooth, indicating that the point mutation was closely linked to sypE. We obtained a single recombinant, however, that formed a wrinkled colony (Fig. 4A). We hypothesized that in this new strain, KV8265, recombination had occurred such that the point mutation was retained and was now linked to the Cmr marker.

FIG 4.

Identification of a mutation in sypF. (A) Chromosomal DNAs containing ΔsypE::FRT-Cm and flanking sequences were introduced into the wrinkling-competent strain (ΔbinK ΔsypE *) (KV7856) by natural transformation with selection for Cmr. The resulting colonies were smooth (1) because the incoming DNA repaired the point mutation. There was one exception, a single recombinant that wrinkled, KV8265 (2). Images on the right represent the outcomes but not the actual strains. (B) Using KV8265 as a template, ΔsypE::FRT-Cm and adjacent sequences of different lengths were amplified in three separate reactions and introduced into V. fischeri by natural transformation and selection for Cmr. The ability of the resulting ΔbinK derivatives to form wrinkled colonies was assessed. Images on the right represent the outcomes but not the actual strains. (C) Sequences that were able to confer wrinkling to the ΔbinK mutant were sequenced, and a mutation was identified in sypF. We termed this allele sypF2. sypF2 contained a single nucleotide deletion at nucleotide 227, resulting in a frameshift that ends the predicted protein after residue 89.

To more precisely determine the position of the point mutation, we performed additional linkage analyses. Using KV8265 as a template, we amplified ΔsypE::Cm and adjacent sequences of different lengths. We introduced these sequences into a recipient strain by natural transformation, selecting for Cmr. Ultimately, we evaluated the resulting colonies for the ability to wrinkle in the absence of BinK (Fig. 4B); if the mutation was transferred to the recipient, the colonies would become wrinkled. Using this approach, we were able to define the position of the mutation as a region within sypF (Fig. 4B). We then sequenced the sypF allele from KV8256 to identify the mutation and found that a single nucleotide was deleted from this gene (Fig. 4C); although other changes existed, none resulted in alterations to the predicted protein sequence. The consequence of the nucleotide deletion is a frameshift that would alter the SypF sequence after codon 76 and end the predicted protein after 89 residues; we termed this allele sypF2. The mutation was also present in parent strain KV3299 but was absent in the wild-type ES114 strain.

Given the presence of sypF2 in the well-characterized ΔsypE mutant, we wondered if our previous conclusions about SypE function were valid. Specifically, our previous work had indicated that SypE was a strong inhibitor of wrinkled colony formation when the response regulator SypG was overexpressed (24, 25), but the presence of the sypF2 mutation made the role of sypE unclear. We therefore compared wrinkled colony formation by sypG-overexpressing strain KV3299 as well as two independently constructed ΔsypE strains that contain wild-type sypF. In contrast to the sypE+ control, which formed smooth colonies, all of the sypE-defective strains, regardless of the presence of sypF2, were competent to form wrinkled colonies (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The presence of sypF2, however, substantially accelerated the timing of wrinkled colony formation. Thus, while the sypF2 allele contributes to the timing of biofilm formation, SypE is, as previously reported, an important negative regulator of wrinkled colony formation.

sypF2 produces an active protein that promotes biofilms.

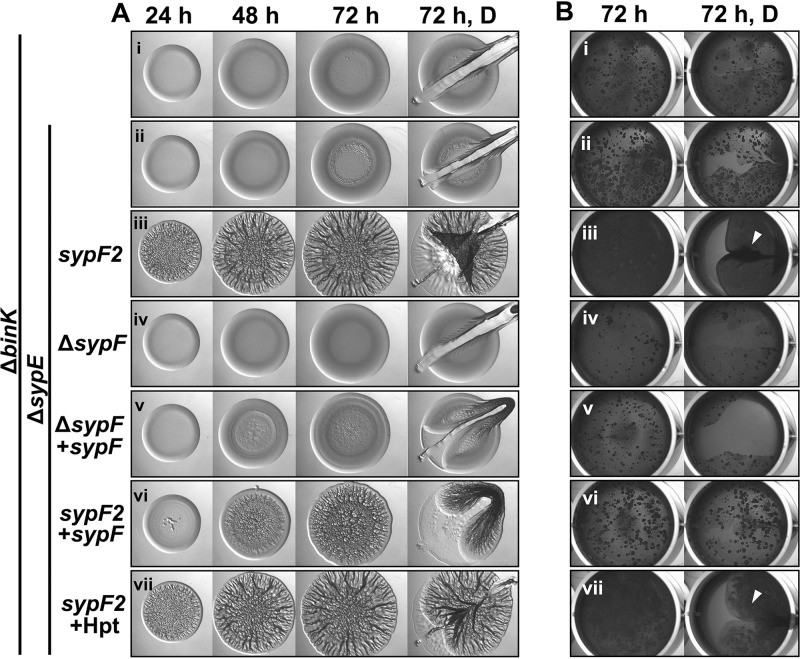

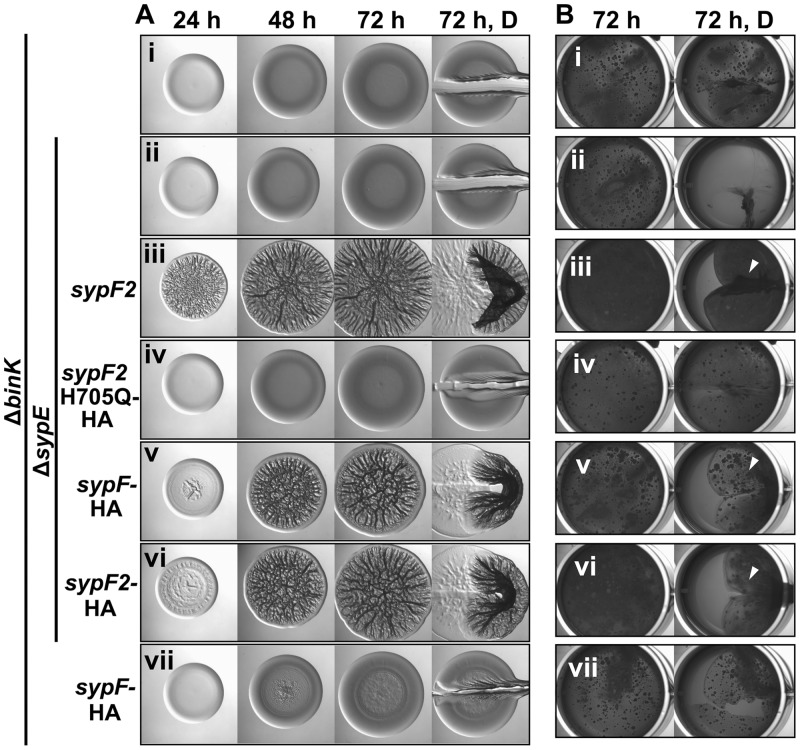

Because a frameshift mutation is typically interpreted as a loss-of-function allele, we asked if SypF is dispensable for wrinkled colony formation in the absence of BinK and SypE. In contrast to the wrinkling-competent sypF2-containing strain, a binK mutant that lacks both sypE and sypF (ΔsypEF) failed to form wrinkled colonies, similar to the ΔbinK and ΔbinK ΔsypE (sypF+) mutants (Fig. 5Ai to iv). In addition, robust wrinkled colony formation could not be restored to the sypEF mutant by the reintroduction of the wild-type sypF allele (Fig. 5Av). Similarly, while the binK sypE sypF2 mutant formed robust pellicles, the binK sypEF mutant failed to do so, similar to the binK and binK sypE (sypF+) mutants (Fig. 5B). Pellicle formation with the same timing could not be restored to the ΔbinK ΔsypEF mutant by complementation with sypF. All of these strains, except for the uncomplemented ΔbinK ΔsypEF mutant, were competent to produce biofilms when grown with calcium, a result that confirms that the complementing sypF allele is functional (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material). Together, these data suggest that (i) sypF2 is not a null allele and thus retains some activity necessary for biofilm formation and (ii) wild-type SypF is not a positive regulator in the absence of calcium but, rather, appears to be a negative regulator.

FIG 5.

Wrinkled colony formation requires SypF activity. (A) Development of wrinkled colony morphology of the indicated strains was assessed at 24, 48, and 72 h. Colonies were disrupted at the final time point to evaluate Syp-PS production. (B) Strains were cultured to log phase, standardized in 2 ml LBS medium in a 24-well microtiter plate, and incubated at 24°C. Development of pellicles was assessed at 72 h. Robust pellicle formation is indicated by the white arrowheads. For both panels A and B, the following strains were evaluated: ΔbinK (KV7860) (i), ΔbinK ΔsypE (KV8391) (ii), ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 (KV7856) (iii), ΔbinK ΔsypEF (KV8055) (iv), ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-FLAG (KV8085) (v), ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 attTn7::sypF-FLAG (KV8404) (vi), and ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 attTn7::sypF-Hpt-FLAG (KV8405) (vii).

We further tested each of these conclusions. First, if sypF2 is not a null allele, then we should be able to disrupt its function. Previous work in other genetic contexts has demonstrated that wrinkled colony formation requires the putative site of phosphotransfer, H705, located within the C-terminal histidine phosphotransferase (Hpt) domain of SypF (11, 21). Therefore, we hypothesized that if cells containing sypF2 retain SypF function, they should also retain the ability to synthesize the Hpt region, including H705. To test the functionality of the C terminus of SypF2, we introduced an H705Q codon mutation into sypF2. We found that the H705Q substitution abrogated biofilm formation by the binK sypE sypF2 strain (Fig. 6Ai to iv and Bi to iv and Fig. S3B). These data support the conclusion that although there is a frameshift mutation in sypF2, the Hpt region of SypF must still be produced.

FIG 6.

SypF functions as a negative regulator. (A) Development of wrinkled colony morphology of the indicated strains was assessed at 24, 48, and 72 h. (B) Strains were cultured to log phase, standardized in 2 ml LBS medium in a 24-well microtiter plate, and incubated at 24°C. Development of pellicles was assessed at 72 h. Robust pellicle formation is indicated by the white arrowheads. For both panels A and B, the following strains were evaluated: ΔbinK (KV7860) (i), ΔbinK::FRT-Cm ΔsypE (KV8390) (ii), ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 (KV7856) (iii), ΔbinK::FRT-Cm ΔsypE sypF2-H705Q-HA (KV8498) (iv), ΔbinK::FRT ΔsypE3 sypF-HA (KV8497) (v), ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2-HA (KV8499) (vi), and ΔbinK sypF-HA (KV8467) (vii).

Multiple lines of evidence supported the conclusion that SypF functions as a negative regulator in the absence of calcium. First, we found that an epitope-tagged version of SypF behaved differently from untagged SypF: in contrast to the smooth colonies produced by the ΔbinK ΔsypE (sypF+) control, a SypF-hemagglutinin (HA)-expressing derivative produced robust wrinkled colonies with timing similar to that of the sypF2 (ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2) strains (Fig. 6Ai to iii, v, and vi). In addition, the expression of SypF-HA in a strain lacking only BinK (sypE+) resulted in modest colony architecture albeit after about 48 h of incubation (Fig. 6Avii). These data suggest that the HA tag perturbs the regulatory function of SypF, resulting in an apparent loss of negative function. Similarly, a closer evaluation of the data from the complementation experiment (Fig. 5Av) revealed that SypF-Flag, expressed from a nonnative position in the chromosome, failed to restore robust wrinkled colony formation yet permitted the production of colonies with subtle architecture. Because ΔbinK ΔsypE (sypF+) double mutant strains form only smooth, noncohesive colonies, these data indicate that the activity of SypF-Flag is also perturbed, diminishing, but not fully disrupting, the negative activity of the protein. Consistent with this conclusion, SypF-Flag exerted a negative effect in the context of SypF2: the introduction of sypF-Flag into the binK sypE sypF2 strain delayed wrinkled colony formation (compare Fig. 5Aiii and vi). In contrast, expression of the isolated Hpt domain alone (SypF-Hpt) did not delay wrinkled colony formation (Fig. 5Avii). Only the ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 strain expressing SypF-Hpt was competent to promote pellicle formation (Fig. 5Bvi and vii), while both strains were competent to promote shaking cell clumping when grown in calcium (Fig. S3A). These data suggest that wild-type SypF, but not the Hpt domain, displays activity that is inhibitory to biofilm formation in the absence of calcium.

We hypothesized that functional, Hpt-containing SypF protein could be produced from sypF2 either due to a mechanism like strand slippage, which would permit some full-length protein to be encoded and synthesized, or by the production of a smaller product from a new transcriptional start site. To distinguish between these hypotheses, we attempted to evaluate the production of SypF2-HA by Western blotting. While we could readily detect the SypF-HA control, we were unable to detect SypF2-HA protein even with an excess of protein loaded, despite clear evidence that the C terminus must be functional (Fig. S4). Thus, SypF2-HA may be unstable and/or made in small amounts. In either case, sufficient SypF2 must be made to generate the observed phenotypes. Together, these data indicate that (i) SypF is a required positive regulator of wrinkled colony and pellicle formation in the absence of added calcium, (ii) full-length SypF exhibits inhibitory activity under these conditions, and (iii) SypF2 has positive activity, which wild-type SypF lacks under these conditions, that depends on H705. We propose that the sypF2 mutation may disconnect the Hpt domain (and other sequences) from the N-terminal transmembrane sensor domain that is predicted to control its activity via a phosphorelay. If this were the case, then the sensor domain of full-length SypF may function to inhibit wrinkled colony formation under these conditions, potentially by promoting phosphatase activity.

The Hpt domain of SypF promotes wrinkled colony formation.

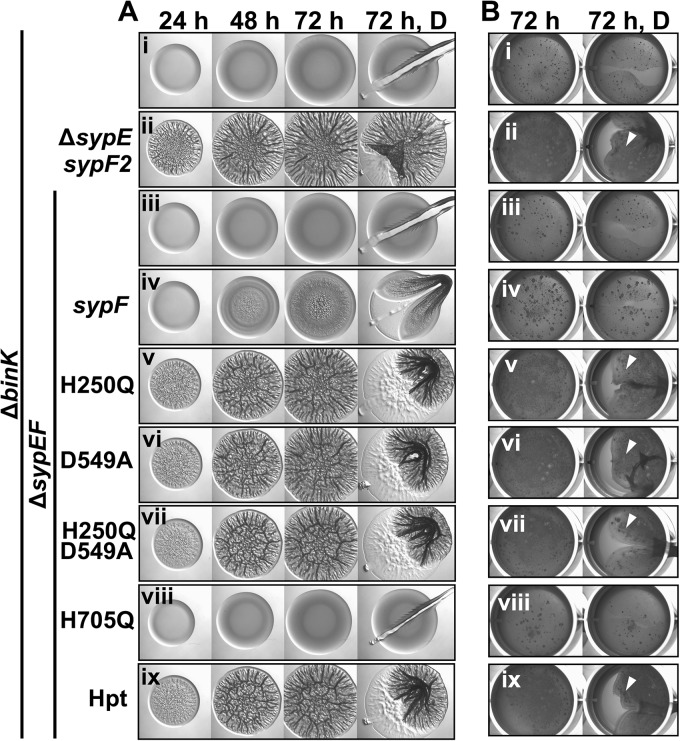

To investigate the mechanism by which SypF controls wrinkled colony formation, we made use of a set of alleles that express SypF variants defective for phosphorelay; we reported previously that only H2 (H705Q), and not H1 (H250Q) or D1 (D549A), is required for biofilm formation (11, 21). We introduced these alleles into the ΔbinK ΔsypEF mutant to see if wrinkled colony formation could be restored. As described above (Fig. 5Av), full-length sypF did not promote robust wrinkled colony formation (Fig. 7Ai to iv). However, biofilms readily formed when mutations were introduced outside the Hpt domain, including H1, D1, or H1D1 (H250Q D549A) (Fig. 7Av to vii). In contrast, SypF-H705Q, which contains a mutation within the Hpt domain, failed to promote wrinkled colony formation (Fig. 7Aviii). Importantly, the expression of the C-terminal Hpt domain alone was sufficient to promote biofilm formation by the ΔbinK ΔsypEF mutant, similar to the sypF2-expressing ΔbinK ΔsypE mutant (Fig. 7Aix). Similarly, the Hpt domain was sufficient to promote pellicles, but SypF-H705Q could not (Fig. 7Bviii and ix). We conclude that SypF-Hpt is sufficient to promote biofilm formation under a variety of conditions, including with RscS overexpression (11, 21) as well as growth without added calcium. Thus, SypF plays both positive and negative roles in biofilm formation, and the experimental conditions used in this study (e.g., the absence of added calcium) promote the inhibitory activity of SypF. Artificially disconnecting the C-terminal signal transduction machinery from the N-terminal sensory domain removes the negative regulation, promoting biofilm formation.

FIG 7.

The Hpt domain of SypF promotes biofilm formation. (A) Development of wrinkled colony morphology of the indicated strains was assessed at 24, 48, and 72 h. Colonies were disrupted at the final time point to evaluate Syp-PS production. (B) Strains were cultured to log phase, standardized in 2 ml LBS medium in a 24-well microtiter plate, and incubated at 24°C. Development of pellicles by the indicated strains was assessed at 72 h. At the end of the time course, the pellicles were disrupted with a toothpick to evaluate pellicle strength. Robust pellicle formation is indicated by the white arrow. For both panels A and B, the following strains were evaluated: ΔbinK (KV7860) (i), ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 (KV7856) (ii), ΔbinK ΔsypE-sypF (KV8055) (iii), ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-FLAG (KV8085) (iv), ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-H250Q-FLAG (KV8406) (v), ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-D549A-FLAG (KV8088) (vi), ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-H250Q-D549A-FLAG (KV8089) (vii), ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-H705Q-FLAG (KV8087) (viii), and ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-Hpt-FLAG (KV8086) (ix).

sypF2 promotes biofilm formation at the level of transcription.

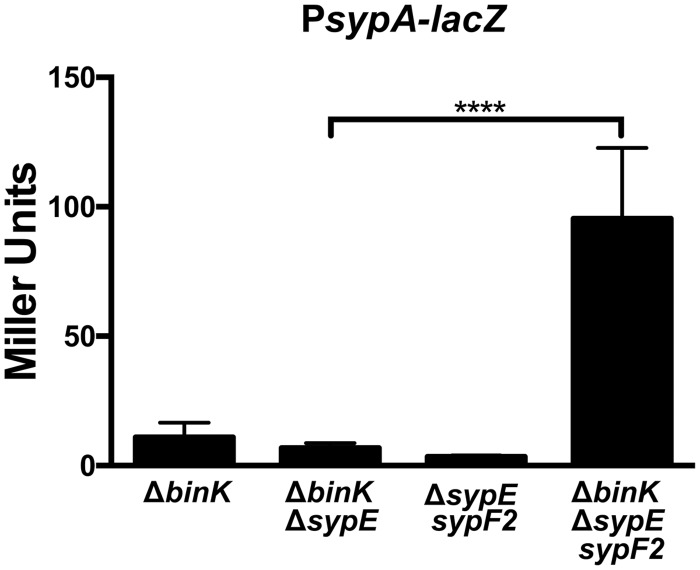

We hypothesized that if SypF is a negative regulator under these conditions, the transcription of the syp locus would be reduced in the presence of wild-type SypF and increased in the presence of SypF2. We assessed the abilities of these respective alleles to promote syp transcription using a lacZ reporter. As previously demonstrated, the binK mutant exhibited low levels of syp transcription in the absence of calcium (11). The binK mutant, the ΔbinK ΔsypE (sypF+) double mutant, and the ΔbinK ΔsypEF triple mutant all exhibited low levels of syp transcription, suggesting that the inhibitory activity of SypF prevents transcription. In contrast, the ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 strain exhibited a significant (P < 0.0001) increase in syp transcription compared to the ΔbinK ΔsypE (sypF+) double mutant (Fig. 8). Thus, the sypF2 allele encodes an active, noninhibitory protein competent to induce syp transcription.

FIG 8.

sypF2 promotes biofilm formation at the level of transcription. Transcription of syp was assessed by evaluating the β-galactosidase activity of the indicated strains carrying a lacZ reporter fusion to the sypA promoter. The following strains were evaluated: ΔbinK (KV8077), ΔbinK::FRT ΔsypE3 (KV8450), ΔsypE sypF2 (KV8451), and ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 (KV8454). These strains also contained a deletion of sypQ, to prevent complications from biofilm formation. The effects of the sypF and sypF2 alleles on syp transcription were evaluated by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

V. fischeri exerts substantial control over biofilm production. Much of the regulation is exerted by two-component regulators, many of which activate transcription of the syp locus. Here, we report our findings that a set of three TCS regulators, BinK, SypE, and SypF, prevents wild-type strain ES114 from forming biofilms in a rich medium in the absence of calcium supplementation. We observed roles for these regulators in preventing wrinkled colony development and pellicle formation. In addition, we determined roles for these regulators in inhibiting the start of biofilm formation in liquid culture under shaking conditions by observing microscopic cell aggregation. Together, data from this work reveal that, in addition to substantial positive regulation, V. fischeri exerts significant negative regulation over biofilm formation.

Negative regulation by TCS in bacteria is not uncommon. For example, multiple TCS regulators control bioluminescence in Vibrio harveyi. At low cell density, three SKs function as kinases to inhibit the production of light by promoting the phosphorylation of the RR LuxO, which in turn indirectly inhibits light production. At high cell density, the three SKs function as phosphatases to dephosphorylate LuxO, inactivating LuxO and allowing light production (30). The loss of a single SK does not prevent cell density-dependent control over bioluminescence. Similarly, the loss of a single negative biofilm regulator in V. fischeri does not prevent inhibition of biofilm formation.

BinK and SypE have previously been shown to function as negative regulators (11, 24, 26, 27, 29). The exact function of BinK is not yet known, but BinK negatively impacts biofilm formation via syp transcription (11, 26). In contrast, SypE appears to work posttranscriptionally as a serine kinase/phosphatase. While the target of SypE's activity is known, it is unclear how phosphorylation of the target impairs biofilm production. The impact of SypE is also substantial: wild-type cells that overexpress the direct syp transcription factor sypG fail to form wrinkled colonies in the presence of SypE. Because these two regulators have negative roles, it was reasonable to hypothesize that together they were sufficient to prevent biofilm formation, and our initial data supported this hypothesis. However, analysis with additional binK sypE mutants suggested that the original sypE strain, used in numerous studies, carried an additional mutation in sypF. We found that this point mutation, while impacting the magnitude of the effect of the sypE mutation on wrinkled colony formation, was not responsible for it. Thus, previous work demonstrating the role of SypE as a negative regulator remains valid.

Our ability to map the mutation, and to readily generate multiple additional binK sypE double mutants, was possible only due to relatively recent advances in the genetic manipulation of V. fischeri. Natural transformation of DNA into V. fischeri has been possible since 2010 (31), but the first use of this technology to map mutations was reported in 2015 (32). More recently, tools have been developed to rapidly generate deletions and insertions using PCR-generated DNA (33). Those genetic advances facilitated our studies by supporting the rapid generation of strains with different mutation combinations and/or the addition of an epitope tag to a gene at its native chromosomal location, as well as by permitting us to map unmarked mutations via linkage analysis. These genetic tools, and their new uses in this study, provide a roadmap for future genetic manipulations of V. fischeri.

The point mutation in sypF, a one-base deletion early in the gene, is predicted to cause a frameshift mutation that should disrupt the function of this gene. Because previous work had demonstrated that SypF plays a vital positive role in biofilm formation, with the C-terminal Hpt domain being necessary and sufficient for SypF function (11, 21), we hypothesized that the point mutation must not prevent the expression of the Hpt domain. While we cannot rule out a role for a truncated N-terminal SypF protein in promoting biofilm formation, several lines of evidence support the conclusion that the SypF2 Hpt domain is made and functional: (i) the ΔbinK ΔsypEF mutant failed to form biofilms, indicating that SypF function is required; (ii) the expression of SypF-Hpt permitted biofilm formation in this background albeit with altered timing; (iii) the ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 strain, but not the ΔbinK ΔsypE strain, produced high levels of syp transcription; and (iv) the activity of SypF2 is lost upon mutation of the hpt domain. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that SypF2 not only is functional but also has increased positive activity relative to wild-type SypF. Of particular note is the finding that the expression of SypF delays biofilm formation by the ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 strain, while the expression of SypF-Hpt does not. These data indicate that full-length SypF exhibits inhibitory activity. Because many sensor kinases also function as phosphatases, it is likely, given our results, that wild-type SypF can function as a phosphatase to inhibit syp transcription and biofilm formation. We hypothesize that SypF2 lacks the N-terminal signaling domain and thus contains only downstream signal transduction domains. Such a truncated protein would be separated from the natural control mechanism that, presumably, promotes phosphatase activity, permitting increased activity, as we observed. Thus, we conclude that SypF functions as both a positive and a negative regulator of biofilm formation by V. fischeri, with the negative activity dominating under the conditions used here. Although additional work will be necessary to determine what signal(s) controls the activities of SypF, these studies provide conditions under which such a signal(s) can be identified.

Our work included an assessment of a variety of strains that contained active forms of only one or two of the three negative regulators. Single ΔbinK and double ΔsypE sypF2 and ΔbinK ΔsypE (sypF+) mutants produced smooth colonies, with only the latter strain producing slight colony architecture and stickiness after prolonged growth. While we have yet to generate a ΔbinK sypF2 double mutant, we observed, with some surprise, that a ΔbinK mutant that expresses HA-tagged SypF produced colonies with subtle three-dimensional (3D) architecture albeit after ∼2 days of growth. The additional absence of sypE resulted in robust wrinkled colony development. These data suggest that the HA tag perturbs SypF's negative regulatory function to nearly the same extent as the original sypF2 mutation. Together, these data indicate that all of these negative regulators contribute to preventing wrinkled colony formation, with BinK potentially being the most important.

Consistent with the conclusion that BinK is the most important of the three regulators, we recently reported that calcium supplementation permits a binK mutant to form biofilms, including wrinkled colonies on plates, pellicles in static culture, and clumps/rings in shaking cultures; these calcium-induced phenotypes do not require any additional mutations (e.g., sypE or sypF) (11). The amount of calcium (10 mM) used to induce biofilm formation is physiologically relevant, as it is similar to the amount found in seawater (28), although it remains unclear what influence calcium in seawater has on symbiotic processes. It is also unknown how calcium overcomes the inhibitory activities of SypE and SypF. One simple explanation would be that calcium induces the phosphorylation of SypF (e.g., by activating its kinase activity [11]). SypF would, in turn, inactivate SypE (21, 25). However, calcium can induce biofilm formation by the binK mutant that expresses only SypF-Hpt, suggesting that this explanation is not sufficient. An alternative explanation is that other factors are involved. In support of this possibility, we find that the ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 strain, which proficiently produces wrinkled colonies, fails to form clumps and rings in shaking cultures in the absence of calcium. Similar results have been observed with other biofilm-competent strains (11). Our findings thus identify BinK, SypE, and SypF as negative biofilm regulators in the absence of calcium supplementation and indicate that additional regulation controls shaking cell clumping; whether calcium inactivates the SypE- and/or SypF-dependent negative regulatory mechanisms or bypasses them remains to be determined.

In summary, this work advances our understanding of biofilm control by V. fischeri by identifying a set of three negative regulators whose coordinate activities prevent biofilm formation in the absence of added calcium. This study also reports a negative regulatory activity for SypF, a protein whose activity is required for biofilm formation. Together, these findings underscore the importance of biofilm control to V. fischeri as well as reveal conditions under which signal transduction processes can be investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

V. fischeri strains used in this study are listed in Table 1, and plasmids used are listed in Table 2. V. fischeri strains were derived by conjugation or natural transformation. Escherichia coli GT115 (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA), π3813 (34), Tam1λpir, Tam1, DH5α, and S17-1λpir were used (35) for cloning and conjugation experiments (36, 37). V. fischeri strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) salt (LBS) medium (38). The following antibiotics were added to LBS medium at the indicated concentrations: chloramphenicol (Cm) at 1 or 2.5 μg ml−1, erythromycin at 2.5 μg ml−1, and tetracycline (Tc) at 2.5 μg ml−1. E. coli strains were cultured in LB medium (39) containing 10 g Bacto tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 10 g NaCl per liter. The following antibiotics were added to LB medium at the indicated concentrations: kanamycin (Kan) at 50 μg ml−1, Tc at 15 μg ml−1, and ampicillin (Ap) at 100 μg ml−1. For solid media, agar was added to a final concentration of 1.5%.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypea | Derivationb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES114 | Wild type | 36 | |

| KV3299 | ΔsypE | 23 | |

| KV6439 | ΔsypEF | Derived from ES114 using pANN17 | This study |

| KV6782 | ΔsypE | Derived from ES114 using pANN40 | This study |

| KV7410 | IG(yeiR-glmS)::PsypA-lacZ attTn7::Emr | 21 | |

| KV7856 | ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 | Derived from KV3299 using pLL2 | This study |

| KV7860 | ΔbinK | 11 | |

| KV7945 | ΔbinK::FRT-Em ΔsypE sypF2 | NT KV3299 using PCR DNA generated with primers 2091 and 1268 (ES114), 2097 and 2098 (pKV494), and 2092 and 1271 (ES114) | This study |

| KV8055 | ΔbinK ΔsypEF | Derived from KV6439 using pLL2 | This study |

| KV8077 | ΔbinK ΔsypQ::FRT-Cm IG(yeiR-glmS)::PsypA-lacZ attTn7::Emr | 11 | |

| KV8069 | ΔsypQ::FRT-Cm | 11 | |

| KV8085 | ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-FLAG | Derived from KV8055 using pANN20 | This study |

| KV8086 | ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-Hpt-FLAG | Derived from KV8055 using pANN50 | This study |

| KV8087 | ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-H705Q-FLAG | Derived from KV8055 using pANN45 | This study |

| KV8088 | ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-D549A-FLAG | Derived from KV8055 using pANN21 | This study |

| KV8089 | ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-H250Q-D549A-FLAG | Derived from KV8055 using pANN65 | This study |

| KV8124 | ΔbinK::FRT-Cm | NT ES114 using PCR DNA generated with primers 2091 and 1268 (ES114), 2089 and 2090 (pKV495), and 2092 and 1271 (ES114) | This study |

| KV8151 | ΔsypE::FRT-Cm | NT ES114 using PCR DNA generated with primers 460 and 2263 (ES114), 2089, and 2090 (pKV495), and 2264 and 425 | This study |

| KV8265 | ΔbinK ΔsypE::FRT-Cm sypF2 | NT KV7856 with chKV8151 | This study |

| KV8389 | ΔbinK::FRT-Cm ΔsypE sypF2 | NT KV3299 with chKV8124 | This study |

| KV8390 | ΔbinK::FRT-Cm ΔsypE3 | NT KV6782 with chKV8124 | This study |

| KV8391 | ΔbinK ΔsypE::FRT-Cm | NT KV7860 with chKV8151 | This study |

| KV8404 | ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 attTn7::sypF-FLAG | Derived from KV7856 using pANN20 | This study |

| KV8405 | ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 attTn7::sypF-Hpt-FLAG | Derived from KV7856 using pANN50 | This study |

| KV8406 | ΔbinK ΔsypEF attTn7::sypF-H250Q-FLAG | Derived from KV8055 using pANN45 | This study |

| KV8419 | ΔbinK::FRT ΔsypE3 IG(yeiR-glmS)::PsypA-lacZ attTn7::Emr | NT KV8512 with chKV7410 | This study |

| KV8420 | ΔsypE sypF2 IG(yeiR-glmS)::PsypA-lacZ attTn7::Emr | NT KV3299 with chKV7410 | This study |

| KV8450 | ΔbinK::FRT ΔsypE3 ΔsypQ::FRT-Cm IG(yeiR-glmS)::PsypA-lacZ attTn7::Emr | NT KV8419 with chKV8069 | This study |

| KV8454 | ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 ΔsypQ::FRT-Cm IG(yeiR-glmS)::PsypA-lacZ attTn7::Emr | NT KV7856 with chKV8069, followed by NT with chKV7410 | This study |

| KV8467 | ΔbinK sypF-HA IG(sypF-sypG)::Emr | NT KV7860 with chKV8497 | This study |

| KV8469 | ΔbinK::FRT-Em ΔsypE::FRT-Cm | NT KV7945 using PCR DNA generated with primers 1157 and 425 (KV8265) | This study |

| KV8470 | ΔbinK::FRT-Em ΔsypE::FRT-Cm sypF2 | NT KV7945 using PCR DNA generated with primers 1157 and 425 (KV8265) | This study |

| KV8497 | ΔbinK::FRT ΔsypE3 sypF-HA IG(sypF-sypG)::Emr | NT KV8512 using PCR DNA generated with primers 1223 and 2348 (ES114), 2089 and 2090 (pKV494), and 2362 and 271 (ES114) | This study |

| KV8498 | ΔbinK::FRT-Cm ΔsypE sypF2-H705Q-HA IG(sypF-sypG)::Emr | NT KV3299 using PCR DNA generated with primers 1223 and 1793 (KV8497) and primers 1794 and 271 (KV8497), followed by NT with chKV8124 | This study |

| KV8499 | ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2-HA IG(sypF-sypG)::Emr | NT KV7856 with chKV8467 | This study |

| KV8512 | ΔbinK::FRT ΔsypE3 | Removal of Cm cassette from KV8390 with Flp (pKV496) | This study |

IG, intergenic.

Derivation of strains constructed in this study. NT, natural transformation of a pLostfoX- or pLostfoX-Kan-carrying version of the strain with the indicated chromosomal (ch) DNA or with a PCR SOEing product generated by using the indicated primers and templates (in parentheses).

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pANN17 | Derivative of pKV363 + sequences flanking sypEF | 21 |

| pANN20 | pEVS107 + Plac-sypF-FLAG | 21 |

| pANN21 | pEVS107 + Plac-sypF-D549A-FLAG | 21 |

| pANN24 | pEVS107 + Plac-sypF-H250Q-FLAG | 21 |

| pANN32 | pKV363 + sequences flanking sypE and sypF, generated with primers 1219 and 519 and primers 1249 and 1375 | This study |

| pANN40 | pKV363 + sequences flanking sypE, generated with primers 1219 and 519 and primers 1220 and 684 | This study |

| pANN45 | pEVS107 + Plac-sypF-H705Q-FLAG | 21 |

| pANN50 | pEVS107 + Plac-sypF-Hpt-FLAG | 21 |

| pANN65 | pEVS107 + Plac-sypF-H250Q-D549A-FLAG | 21 |

| pCLD56 | pKV282 + sypG | 24 |

| pEVS104 | Conjugal plasmid | 50 |

| pEVS107 | Tn7 delivery plasmid; Emr Kmr | 44 |

| pEVS170 | Vector containing Emr Kmr | 51 |

| pJET | Commercial cloning vector; Apr | Thermo Fisher |

| pKV282 | Low-copy-no. vector; Tcr | 25 |

| pKV363 | Suicide plasmid | 37 |

| pKV494 | pJET + FRT-Emr | 33 |

| pKV495 | pJET + FRT-Cmr | 33 |

| pKV496 | pJET + Flp recombinase | 33 |

| pLL2 | pKV363 + sequences flanking binK | 11 |

| pLosTfoX | Expresses TfoX; Cmr | 31 |

| pLostfoX-Kan | Expresses TfoX; Kmr | 46 |

| pUX-BF13 | Tn7 transposase-expressing vector | 52 |

Details on construction are included for plasmids generated in this study; ES114 was used as a template for PCRs.

Bioinformatics.

Sequences for V. fischeri sypF (VF_A1025) were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. Alignments of sypF and sypF2 were generated by using BLAST and the Clustal Omega multiple-sequence alignment program from the EMBL-EBI (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) (40–43).

Molecular and genetic techniques.

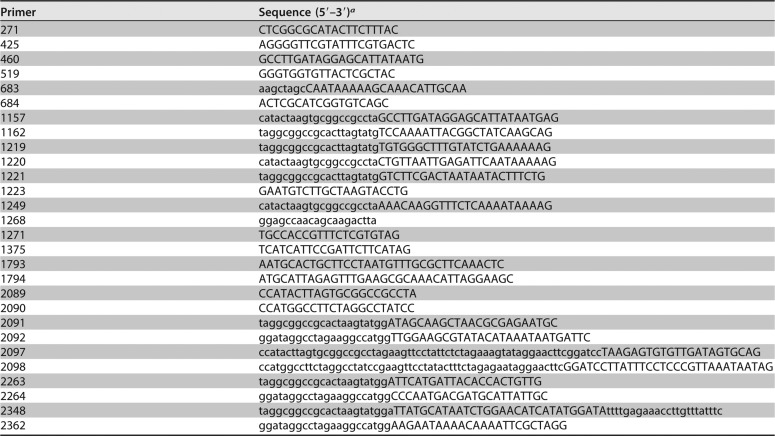

The binK, sypE, and sypF alleles used in this study were generated, and, in some cases, HA epitope tagged, by PCR using primers listed in Table 3. All pARM47-based constructs were inserted into the chromosomal Tn7 site of V. fischeri strains by using tetraparental conjugation (44). E. coli strains described above were used for the purposes of cloning, plasmid maintenance, and conjugation. Derivatives of V. fischeri were generated via conjugation (45) or by natural transformation (31, 46). PCR SOEing (splicing by overlap extension) (47) reactions were performed by using EMD Millipore Novagen KOD high-fidelity polymerase, and Promega Taq was used to confirm gene replacement events. To generate epitope-tagged sypF, sequences (∼500 bp) upstream and downstream of sypF were amplified by PCR and then fused with an HA epitope tag and an Emr cassette in a PCR SOEing reaction. The final spliced PCR product was introduced into tfoX-overexpressing ES114 by natural transformation. The antibiotic resistance marker was used to select for the desired gene replacement mutant, generated by recombination of the PCR product into the chromosome. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from ES114 recombinants by using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen) or the Quick-DNA Microprep kit (Zymogen).

TABLE 3.

Primers

aLowercase type indicates “tails” added to the PCR product that were not complementary to the target DNA.

Linkage analysis and sequencing.

Linkage of ΔsypE::Cm to sypF2 was assessed through the natural transformation of a ΔbinK ΔsypE sypF2 strain using chromosomal ΔsypE::Cm DNA, resulting in ΔbinK ΔsypE::Cm sypF2, and was confirmed by sequencing. To perform the linkage analysis of sypF2, ΔsypE::Cm linked to sypF2 and adjacent sequences of various lengths were amplified. Three reactions were performed in the linkage analysis amplifying ΔsypE::Cm and sypF2, with 1157 as the forward primer and the following reverse primers: 425, 1221, and 1162. PCR amplification was performed by using EMD Millipore Novagen KOD high-fidelity polymerase or Invitrogen AccuPrime high-fidelity Taq polymerase. The final PCR product was introduced into the tfoX-overexpressing ΔbinK strain by natural transformation. The antibiotic resistance marker was used to select for the desired gene replacement mutant, generated by recombination of the PCR product into the chromosome. Because the tfoX-overexpressing ΔbinK mutant exhibited decreased transformation efficiency relative to the wild type, in some cases the PCR products were first introduced into ES114, followed by the introduction of a marked ΔbinK allele into multiple original colonies. Specifically, for the recombination events indicated in Fig. 4B (sequences 1 and 2), KV8265 was used as a template for PCR with primers 1157 and 425 (template KV8265) and then used to transform ES114. Seven colonies that maintained the tfoX plasmid were isolated on medium containing Cm and Km and used as a recipient for transformation with chromosomal DNA from KV7945 (ΔbinK::Tmr). One of these (KV8470) formed wrinkled colonies, while the remainder (represented by KV8469) formed smooth colonies. sypF alleles were sequenced by first amplifying sypF sequences, followed by column purifying the resulting PCR products, which were then sequenced by using primer 425 and, for KV8265, primer 684, 1223, or 2264. KV3299, KV8265, KV8469, and KV8498 contained the frameshift mutation of sypF2, while ES114 and KV8470 contained the wild-type sypF sequence in this region. Sequencing reactions were performed by ACGT, Inc. (Wheeling, IL).

Wrinkled colony formation assay.

To observe wrinkled colony formation, the indicated V. fischeri strains were streaked onto LBS agar plates. Single colonies were then cultured with shaking in 5 ml LBS broth overnight at 28°C. The strains were then subcultured the following day in 5 ml of fresh medium. Following growth to early log phase, the cultures were standardized to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2 by using LBS medium. Ten microliters of diluted cultures was spotted onto LBS agar plates and grown at 24°C. Images of the spotted cultures were acquired over the course of wrinkled colony formation at the indicated times by using a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C dissecting microscope and a Jenoptik Progres Gryphax series Subra camera. At the end of the time course, the colonies were disrupted with a toothpick to assess colony cohesiveness, which is an indicator of symbiosis polysaccharide (Syp-PS) production (48).

Pellicle formation assay.

To assess pellicle formation, V. fischeri strains were grown overnight and subcultured with shaking as described above. Following growth to mid-log phase, the cultures were standardized to an OD600 of 0.2 using LBS medium in a 24-well microtiter plate. Inoculated microtiter plates were incubated statically at 24°C. Images of the microtiter wells were acquired over the course of pellicle formation at the indicated times by using a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C dissecting microscope and a Jenoptik Progres Gryphax series Subra camera. At the end of the time course, the pellicles were disrupted with a toothpick to assess pellicle strength.

Microscopic aggregation assay.

Differential interference contrast (DIC) images of strains grown without calcium were assessed for aggregation by using an Optronics MagnaFire S60800 charge-coupled-device (CCD) microscope camera attached to a Leica DM IRB with a Prior Lumen 200 light source. Images were taken at a ×200 magnification (20× objective lens and 10× eyepiece).

β-Galactosidase assay.

Strains carrying a lacZ reporter fusion to the sypA promoter were grown in triplicate at 24°C in LBS medium. Strains were subcultured in 20 ml of fresh medium in 125-ml baffled flasks, the OD600 was measured, and samples (1 ml) were collected after 22 h of growth. Cells were resuspended in Z-buffer and lysed with chloroform. The β-galactosidase activity of each sample was assayed as described previously (49) and measured by using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek). The assay was performed at least three independent times. Statistical analysis was performed by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Valerie Ray, Louise Lie, and Allison Norsworthy for strain construction and members of the laboratory for thoughtful discussions and review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 GM114288 awarded to K.L.V. and by the Wheaton College Aldeen Grant awarded to J.K.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01257-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donlan RM. 2001. Biofilms and device-associated infections. Emerg Infect Dis 7:277–281. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flemming HC, Neu TR, Wozniak DJ. 2007. The EPS matrix: the “house of biofilm cells.” J Bacteriol 189:7945–7947. doi: 10.1128/JB.00858-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flemming HC, Wingender J. 2010. The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:623–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Toole G, Kaplan HB, Kolter R. 2000. Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu Rev Microbiol 54:49–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McFall-Ngai M. 2014. Divining the essence of symbiosis: insights from the squid-vibrio model. PLoS Biol 12:e1001783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McFall-Ngai MJ. 2014. The importance of microbes in animal development: lessons from the squid-vibrio symbiosis. Annu Rev Microbiol 68:177–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091313-103654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stabb E, Visick K. 2013. Vibrio fischeri: a bioluminescent light-organ symbiont of the bobtail squid Euprymna scolopes, p 497–532. In Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Lory S, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F (ed), The prokaryotes, 4th ed Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visick KL. 2009. An intricate network of regulators controls biofilm formation and colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 74:782–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyholm SV, Stabb EV, Ruby EG, McFall-Ngai MJ. 2000. Establishment of an animal-bacterial association: recruiting symbiotic vibrios from the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:10231–10235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darnell CL, Hussa EA, Visick KL. 2008. The putative hybrid sensor kinase SypF coordinates biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri by acting upstream of two response regulators, SypG and VpsR. J Bacteriol 190:4941–4950. doi: 10.1128/JB.00197-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tischler AH, Lie L, Thompson CM, Visick KL. 2018. Discovery of calcium as a biofilm-promoting signal for Vibrio fischeri reveals new phenotypes and underlying regulatory complexity. J Bacteriol 200:e00016-. doi: 10.1128/JB.00016-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yip ES, Geszvain K, DeLoney-Marino CR, Visick KL. 2006. The symbiosis regulator rscS controls the syp gene locus, biofilm formation and symbiotic aggregation by Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 62:1586–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem 69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galperin MY. 2010. Diversity of structure and function of response regulator output domains. Curr Opin Microbiol 13:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wuichet K, Cantwell BJ, Zhulin IB. 2010. Evolution and phyletic distribution of two-component signal transduction systems. Curr Opin Microbiol 13:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung K, Fried L, Behr S, Heermann R. 2012. Histidine kinases and response regulators in networks. Curr Opin Microbiol 15:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uhl MA, Miller JF. 1996. Integration of multiple domains in a two-component sensor protein: the Bordetella pertussis BvgAS phosphorelay. EMBO J 15:1028–1036. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.West AH, Stock AM. 2001. Histidine kinases and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems. Trends Biochem Sci 26:369–376. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01852-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenney LJ. 2010. How important is the phosphatase activity of sensor kinases? Curr Opin Microbiol 13:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibata S, Yip ES, Quirke KP, Ondrey JM, Visick KL. 2012. Roles of the structural symbiosis polysaccharide (syp) genes in host colonization, biofilm formation, and polysaccharide biosynthesis in Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 194:6736–6747. doi: 10.1128/JB.00707-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norsworthy AN, Visick KL. 2015. Signaling between two interacting sensor kinases promotes biofilms and colonization by a bacterial symbiont. Mol Microbiol 96:233–248. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yip ES, Grublesky BT, Hussa EA, Visick KL. 2005. A novel, conserved cluster of genes promotes symbiotic colonization and sigma-dependent biofilm formation by Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 57:1485–1498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussa EA, Darnell CL, Visick KL. 2008. RscS functions upstream of SypG to control the syp locus and biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 190:4576–4583. doi: 10.1128/JB.00130-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris AR, Visick KL. 2013. Inhibition of SypG-induced biofilms and host colonization by the negative regulator SypE in Vibrio fischeri. PLoS One 8:e60076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris AR, Darnell CL, Visick KL. 2011. Inactivation of a novel response regulator is necessary for biofilm formation and host colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 82:114–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks JF II, Mandel MJ. 2016. The histidine kinase BinK is a negative regulator of biofilm formation and squid colonization. J Bacteriol 198:2596–2607. doi: 10.1128/JB.00037-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pankey SM, Foxall RL, Ster IM, Perry LA, Schuster BM, Donner RA, Coyle M, Cooper VS, Whistler CA. 2017. Host-selected mutations converging on a global regulator drive an adaptive leap towards symbiosis in bacteria. Elife 6:e24414. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pilson MEQ. 1998. An introduction to the chemistry of the sea. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris AR, Visick KL. 2013. The response regulator SypE controls biofilm formation and colonization through phosphorylation of the syp-encoded regulator SypA in Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 87:509–525. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng WL, Bassler BL. 2009. Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu Rev Genet 43:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollack-Berti A, Wollenberg MS, Ruby EG. 2010. Natural transformation of Vibrio fischeri requires tfoX and tfoY. Environ Microbiol 12:2302–2311. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks JF II, Gyllborg MC, Kocher AA, Markey LE, Mandel MJ. 2015. TfoX-based genetic mapping identifies Vibrio fischeri strain-level differences and reveals a common lineage of laboratory strains. J Bacteriol 197:1065–1074. doi: 10.1128/JB.02347-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Visick KL, Hodge-Hanson KM, Tischler AH, Bennett AK, Mastrodomenico V. 2018. Tools for rapid genetic engineering of Vibrio fischeri. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e00850-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00850-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Roux F, Binesse J, Saulnier D, Mazel D. 2007. Construction of a Vibrio splendidus mutant lacking the metalloprotease gene vsm by use of a novel counterselectable suicide vector. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:777–784. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02147-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Biotechnology 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boettcher KJ, Ruby EG. 1990. Depressed light emission by symbiotic Vibrio fischeri of the sepiolid squid Euprymna scolopes. J Bacteriol 172:3701–3706. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3701-3706.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visick KL, Skoufos LM. 2001. Two-component sensor required for normal symbiotic colonization of Euprymna scolopes by Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 183:835–842. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.835-842.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stabb EV, Reich KA, Ruby EG. 2001. Vibrio fischeri genes hvnA and hvnB encode secreted NAD(+)-glycohydrolases. J Bacteriol 183:309–317. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.309-317.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis RW. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics: a manual for genetic engineering. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altschul SF, Wootton JC, Gertz EM, Agarwala R, Morgulis A, Schäffer AA, Yu YK. 2005. Protein database searches using compositionally adjusted substitution matrices. FEBS J 272:5101–5109. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCann J, Stabb EV, Millikan DS, Ruby EG. 2003. Population dynamics of Vibrio fischeri during infection of Euprymna scolopes. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:5928–5934. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.5928-5934.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeLoney CR, Bartley TM, Visick KL. 2002. Role for phosphoglucomutase in Vibrio fischeri-Euprymna scolopes symbiosis. J Bacteriol 184:5121–5129. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.18.5121-5129.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brooks JF II, Gyllborg MC, Cronin DC, Quillin SJ, Mallama CA, Foxall R, Whistler C, Goodman AL, Mandel MJ. 2014. Global discovery of colonization determinants in the squid symbiont Vibrio fischeri. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:17284–17289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415957111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ray VA, Driks A, Visick KL. 2015. Identification of a novel matrix protein that promotes biofilm maturation in Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 197:518–528. doi: 10.1128/JB.02292-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stabb EV, Ruby EG. 2002. RP4-based plasmids for conjugation between Escherichia coli and members of the Vibrionaceae. Methods Enzymol 358:413–426. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)58106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lyell NL, Dunn AK, Bose JL, Vescovi SL, Stabb EV. 2008. Effective mutagenesis of Vibrio fischeri by using hyperactive mini-Tn5 derivatives. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:7059–7063. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01330-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bao Y, Lies DP, Fu H, Roberts GP. 1991. An improved Tn7-based system for the single-copy insertion of cloned genes into chromosomes of gram-negative bacteria. Gene 109:167–168. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90604-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.