Abstract

Purpose:

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a common and potentially dose-limiting side effect of neurotoxic chemotherapy for cancer patients. We evaluated the preliminary efficacy of acupuncture in preventing worsening CIPN in patients receiving paclitaxel.

Methods:

In this phase IIA single-arm clinical trial, we screened stage I-III breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant/adjuvant weekly paclitaxel for development of CIPN. The primary objective was to assess acupuncture’s efficacy in preventing the escalation of National Cancer Institute-Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 4.0 grade 2 CIPN to higher grades. Acupuncture was deemed worthy of further study if 23 or more of the 27 enrolled patients did not develop grade 3 CIPN. Outcome measures (NCI-CTCAE CIPN grade, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/Gynecologic Oncology Group-Neurotoxicity (FACT/GOG-Ntx), Neuropathic Pain Scale (NPS)) were obtained weekly during the intervention.

Results:

Of 104 patients screened, 37 developed grade 2 CIPN (36%) and 28 (27%) enrolled into the intervention phase; one was removed due to protocol violation. Of the 27 patients receiving acupuncture, 26 completed paclitaxel treatment without developing grade 3 CIPN, meeting our pre-specified success criteria for declaring acupuncture worthy of further study. FACT/GOG-Ntx and NPS scores remained stable during the intervention while continuing weekly paclitaxel. Acupuncture treatment was well tolerated; 4 of 27 (15%) patients reported grade 1 bruising.

Conclusions:

Acupuncture was safe and showed preliminary evidence of effectiveness in reducing the incidence of high grade CIPN during chemotherapy. A follow-up randomized controlled trial is needed to establish definitive efficacy in CIPN prevention for patients at risk.

INTRODUCTION

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a common, potentially painful, debilitating, and dose-limiting side effect of taxane-containing chemotherapy agents affecting 30–40% of breast cancer patients.1 The current management of persistent National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 4.0 (v4.0) grade 2 or higher CIPN during chemotherapy is dose reduction or discontinuation of chemotherapy.2 Results from a recent pilot study of hand cryotherapy during weekly paclitaxel treatment to reduce CIPN have been encouraging,3 and results from a definitive study are pending. However, many patients still develop moderate to severe CIPN during chemotherapy,4 and additional effective CIPN preventative measures are needed.5

Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese medicine technique that may work through its effect on neurotransmitters and neurohormones.6,7 Several studies have suggested that acupuncture may help reduce peripheral neuropathy symptoms in patients with diabetes, human immuno-deficiency virus, or CIPN.8–20

Our group completed a single-arm pilot study on the efficacy of acupuncture treatment for bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy (BIPN) in multiple myeloma patients and showed that among patients experiencing persistent BIPN ≥ grade 2, acupuncture treatments significantly decreased pain and improved function.19 To date, there have not been any risk-based prevention trials to identify the high-risk population that may benefit from an intervention to prevent the worsening of CIPN. This is particularly important because the universal integration of acupuncture as a preventive strategy could be both costly and unnecessary for many patients who may never develop CIPN. Thus, based on the concept of early intervention to prevent escalation of symptoms, we conducted a single-arm phase IIA trial of women who developed CTCAE grade 2 CIPN during neoadjuvant/adjuvant weekly paclitaxel for breast cancer to assess the preliminary safety and efficacy of weekly acupuncture in the prevention of subsequent CIPN progression.

METHODS

Participants

This risk-based trial was conducted in two phases. For the screening phase, eligible participants were aged 21 or older, had an ECOG performance status of 0–2, and planned to receive 12 weekly neoadjuvant/adjuvant paclitaxel chemotherapy treatments at 80mg/m2 for stage I-III breast cancer. Concomitant trastuzumab or carboplatin were allowed in this study. 15 patients received trastuzumab and six patients received carboplatin; one received both with weekly paclitaxel. Exclusion criteria were known metastatic breast cancer; pre-existing peripheral neuropathy within 28 days of screening consent; and current use of anti-neuropathic pain agents such as gabapentin, pregabalin, or duloxetine. In addition to meeting inclusion criteria for the screening phase, patients enrolled in the intervention phase were those who developed NCI-CTCAE grade 2 CIPN by nursing assessment while on weekly paclitaxel chemotherapy. We obtained informed consent from all patients prior to enrollment. The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (ClinicalTrial.gov identifier NCT02364726).

Interventions

During the screening phase, starting from the first week of paclitaxel treatment, chemotherapy nurses screened eligible patients for CIPN weekly using the NCI-CTCAE v4.0 criteria. Per the current standard of care, chemotherapy dosage was changed at the discretion of the treating physician based on patients’ symptoms and other treatment- related toxicity. Patients also completed FACT/GOG-Ntx, and NPS questionnaires prior to each chemotherapy session and three months after chemotherapy completion (±2 weeks). Although initially, we did not collect data on the use of cryotherapy during weekly paclitaxel chemotherapy, we amended the protocol later to include collection of this information.

All patients received usual medical care in addition to the study intervention. We measured CIPN severity using vibration sensation tests at the time of intervention consent and after the final acupuncture session. Chemotherapy dosage, delay, and reasons for the delay were documented during the intervention phase. Blood samples were collected at the time of intervention consent and after the final acupuncture session, but before the final chemotherapy session, to measure brain-derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF) before and after acupuncture.

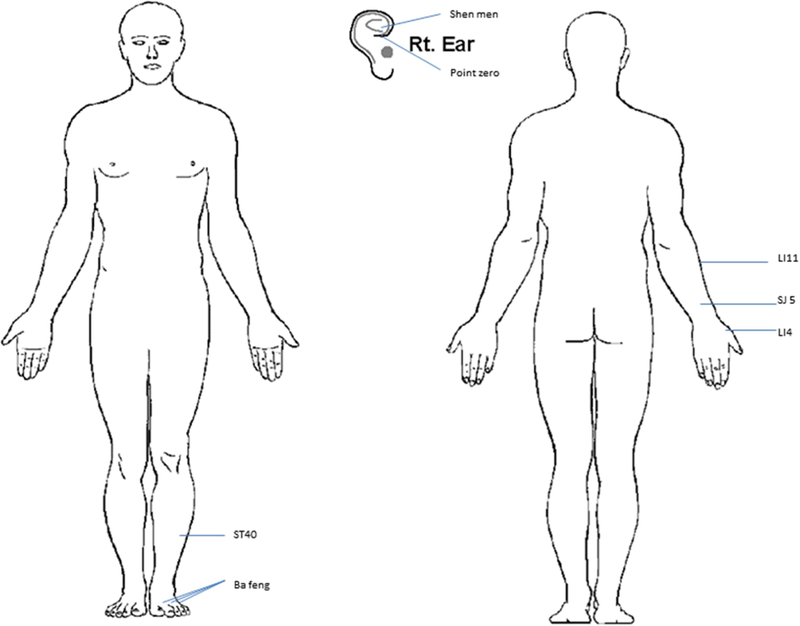

Eligible patients received acupuncture per prior research19 (see Figure 1). After disinfecting the skin with an alcohol swab, acupuncturists inserted filiform 0.16mm x 15mm (or 30mm) sterilized, disposable acupuncture needles in the ear and Ba Feng points; 0.20mm x 30mm (or 40mm) sterilized, disposable acupuncture needles were inserted at body points. Needles for body points were inserted 0.5 inches into the skin and left for 30 minutes after achieving de qi, a sensation of achiness, soreness, and heaviness. Among women with lymphedema associated with mastectomy or lymph node dissection, no needles were placed in the upper extremity on the affected side.

Figure 1.

Acupuncture point locations in bilateral ear points shen men, point zero, and two additional auricular acupuncture points where electrodermal signal was detected; and in bilateral body acupuncture points LI4, TE5, LI11, ST40, and Ba Feng.

Outcomes

The primary study outcome was the proportion of participants who progressed from CIPN grade 2 to grade 3, as assessed by the chemotherapy nurse, at any point during the study. The severity of CIPN was defined by NCI-CTCAE v4.0: grade 1 CIPN, or paresthesia; grade 2, or moderate symptoms limiting instrumental activities of daily living; grade 3, or severe symptoms limiting self-care activities of daily living; and grade 4, or life-threatening consequences for which urgent intervention is indicated.

Secondary outcomes included severity of CIPN as measured by weekly FACT-GOG/Ntx and NPS scores. The FACT/GOG-Ntx questionnaire in this study assessed sensory neuropathy, motor neuropathy, hearing neuropathy, and dysfunction symptoms in patients. The NPS is a multidimensional tool that uses visual analogue scales to quantify global pain intensity and unpleasantness as well as eight other descriptive qualities of neuropathic pain.21,22

Additional secondary study outcomes included relative dose intensity of chemotherapy and vibration sensation using a 128 Hz tuning fork before and after the acupuncture intervention. In addition, we measured plasma BDNF, a nerve growth factor, before and after the acupuncture intervention.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of our study was to assess the efficacy of treating patients with grade 2 CIPN with acupuncture to reduce CIPN severity and prevent the progression of grade 2 CIPN to grade 3 or higher. Our null hypothesis was that the response rate would be 70% after completion of the chemotherapy and acupuncture regimens. The 70% response rate was based on the assumption that all patients with grade 3 or 4 CIPN developed grade 2 at some point during the study and were captured in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 1199 trial in which, of 1,231 breast cancer patients receiving weekly paclitaxel in the adjuvant setting, 27% developed grade 2, 3, or 4 CIPN, and 8% reported grade 3 or 4 neuropathy (none response rate = 30%).23 Our goal was to accrue 27 patients in total. We determined that acupuncture would be deemed worthy of further study if more than 23 of these patients did not develop grade 3 or 4 CIPN (response rate ≥85%). We compared this null hypothesis of 70% against an alternative hypothesis of 90% in optimal Simon two-stage design with an α of 5% and a power of 80%.

For the secondary outcomes, we plotted FACT-GOG/Ntx and NPS scores for the first week of paclitaxel, before the first acupuncture intervention, and after the last acupuncture and chemotherapy treatments. We abstracted information about chemotherapy dosing and schedule from patients’ medical records. The mean vibration sensation test results and BDNF measurements were reported before and after acupuncture, as well as the mean difference between time points with 95% CI. Descriptions about use of cryotherapy were also reported. All analyses were performed using Stata 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

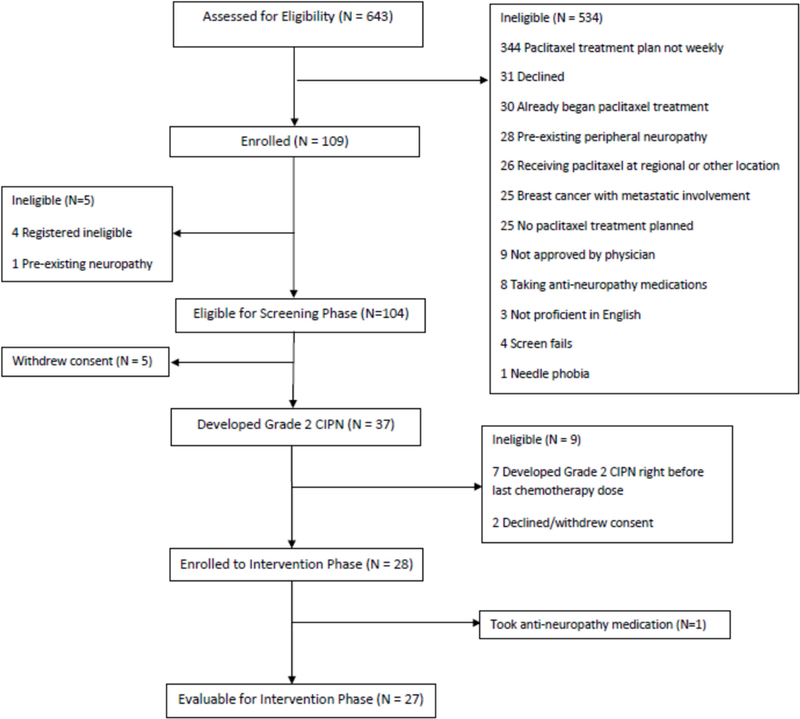

From May 2015 to March 2017, 104 patients were enrolled into the screening phase of the study and 37 (36%) developed grade 2 CIPN. Of these 37 patients, nine were not evaluable: seven developed grade 2 CIPN right before the last dose of weekly paclitaxel chemotherapy leaving inadequate time for the intervention and two declined/withdrew consent, leaving 28 who transitioned to the intervention phase. One patient in the intervention phase was removed from the study for violating the protocol by taking gabapentin on her own, leaving 27 patients in total. The study flow diagram is listed in Figure 2 and patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Study Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| All Patients (N=103) | Screening Group (N=76) |

Intervention Group (N=27) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||

| White | 54 (52%) | 42 (55%) | 12 (44%) |

| Black | 22 (21%) | 13 (17%) | 9 (33%) |

| Asian | 11 (11%) | 9 (12%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Other | 7 (6.8%) | 5 (6.6%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Unknown | 9 (8.7%) | 7 (9.2%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 13 (13%) | 8 (11%) | 5 (19%) |

| Patient age at consent (yrs) | 47 (38, 57) | 48 (38, 57) | 47 (39, 53) |

| Total number of chemotherapy visits | 12 (11, 12) |

Data are presented as median and quartiles or frequency (%).

Among the 27 patients in the intervention phase, with continuation of an average of additional four doses of chemotherapy (mean: 4, SD: 3), only one patient progressed to grade 3 CIPN (4%), nine (33%) remained at grade 2 CIPN, 11 (41%) were downgraded to grade 1 CIPN, and six (22%) were downgraded to grade 0 CIPN in the last week of chemotherapy treatment. We therefore met the pre-specified success criterion that if 23 or more of the enrolled 27 subjects did not develop grade 3 CIPN then acupuncture would be deemed worthy of further study.

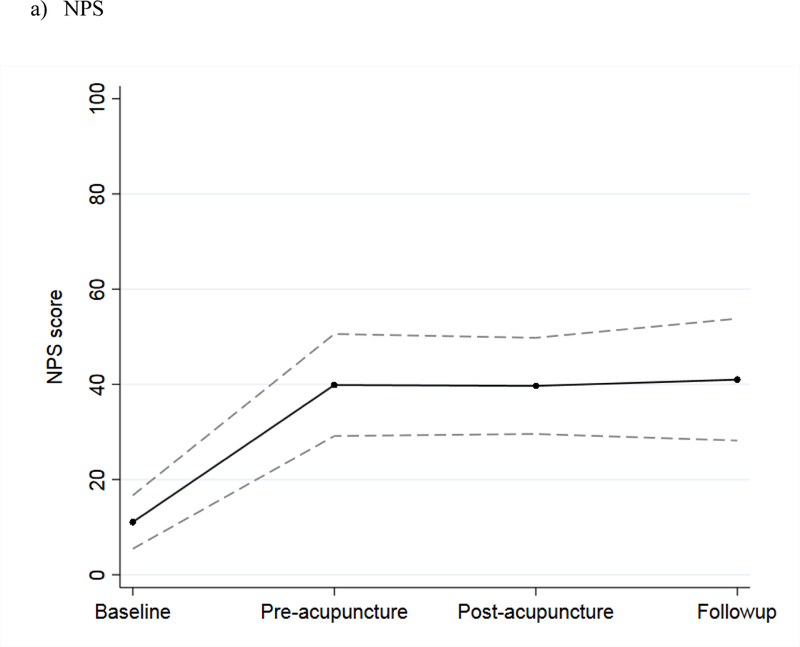

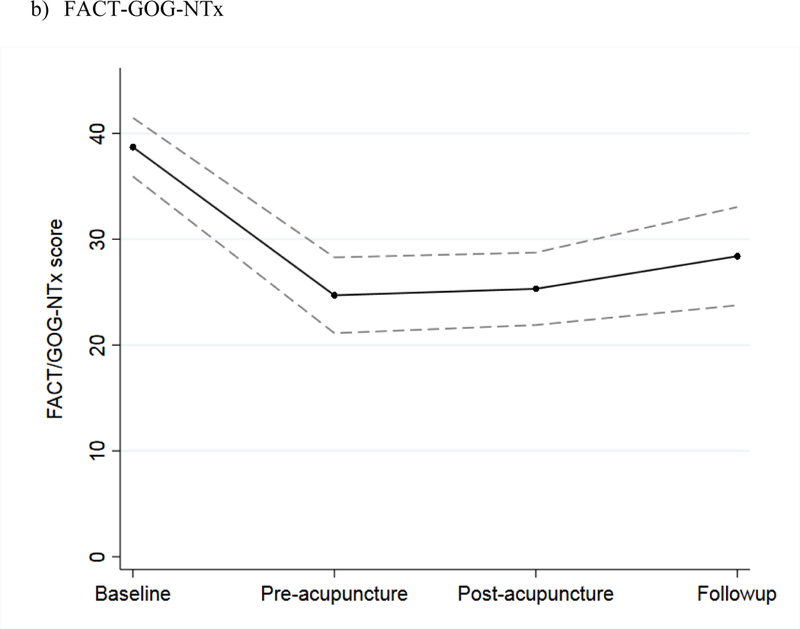

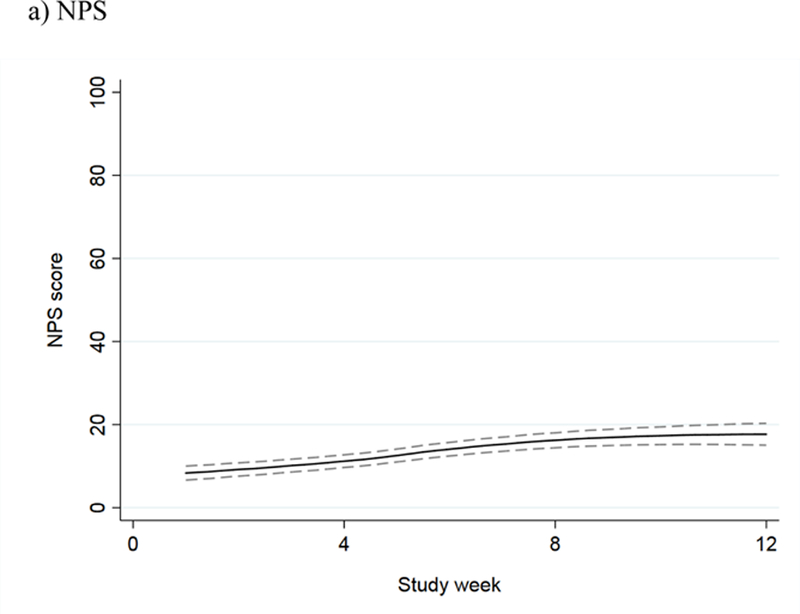

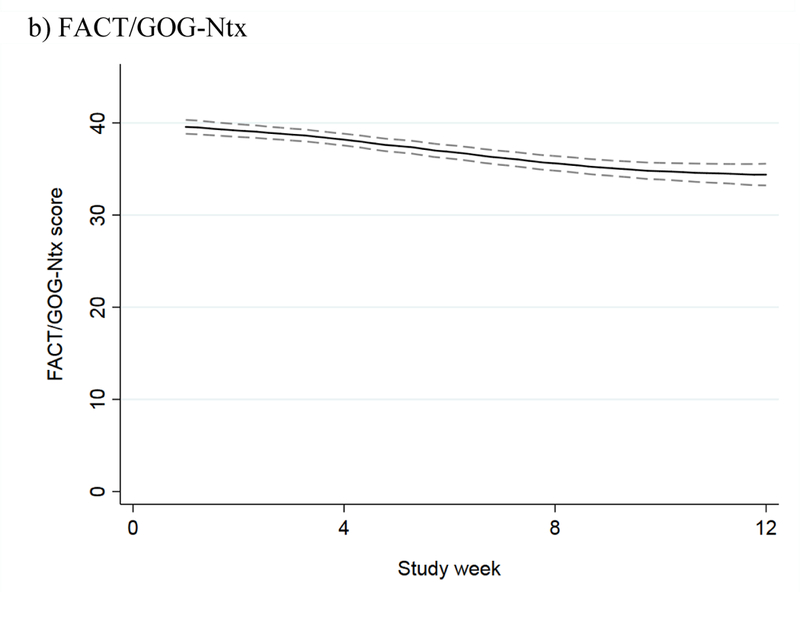

The mean NPS score among the 27 evaluable patients in the intervention phase increased during the screening phase, indicating worsening neuropathy pain; stabilized during the intervention phase; and remained unchanged at the three-month follow-up (Figure 3a). The mean FACT/GOG-Ntx score decreased during the screening phase, indicating worsening CIPN symptoms and function; stabilized during the intervention phase; and increased at the three-month follow-up (Figure 3b). For patients in the screening phase, we collected NPS and FACT/GOG-Ntx scores on a weekly basis. The results showed that both NPS and FACT/GOG-Ntx scores changed to indicate worsening neuropathy symptoms over time (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Mean scores during baseline, before the first acupuncture treatment, after the last acupuncture treatment, and at three-month follow-up among intervention patients, with 95% confidence interval, for: a) NPS and b) FACT/GOG-Ntx scores.

Figure 4.

NPS and FACT/GOG-NTx scores over time during the screening phase, with 95% confidence interval, for: a) NPS (the higher score, the worse CIPN) and b) FACT/GOG-Ntx (the lower score, the worse CIPN).

Among the 27 evaluable patients in the intervention phase, 14 had a paclitaxel treatment-delay. However, only two of these delays were due to CIPN symptoms. The other 12 patients experienced dose delays due to infection (n=4), neutropenia (n=3), anemia (n=2), rash (n=1), cardiomyopathy (n=1), and pneumonitis (n=1). Six patients had a paclitaxel dose-reduction. For two of these patients, the reduction was due to CIPN (one patient’s physician reduced the dose due to grade 3 CIPN and the other patient declined to received the last dose of paclitaxel due to CIPN symptoms). The other four patients’ dose reductions were due to neutropenia (n=1), multiple non-CIPN treatment-induced toxicities and good clinical response in the neoadjuvant setting (n=1), paclitaxel-induced pneumonitis (n=1), and cardiomyopathy and neutropenic fever requiring hospitalization (n=1). Among the 21 patients without any dose reductions, toxicity for the remainder of the treatment regimen was as follows: five remained at grade 2 CIPN, 11 decreased to grade 1, and five decreased to grade 0. Among the 12 patients with no treatment delays or dose reductions, three remained at grade 2 CIPN, six decreased to grade 1, and three decreased to grade 0.

Twenty-four intervention patients completed vibration tests and 16 had available BDNF measurements at both the time of intervention consent and last acupuncture treatment. There was no evidence of significant differences in either vibration test results (mean difference 0.49, 95% CI −1.61, 2.60, p=0.6) or BDNF measurements (mean difference 148, 95% CI −740, 1035, p=0.7) taken before and after acupuncture treatment.

Cryotherapy data were available for 21 of the 27 patients in the intervention phase. Of these 21 patients, three did not receive cryotherapy; 18 initiated cryotherapy at weeks 1–4 (median: week 1) and continued weekly cryotherapy during chemotherapy. They then developed grade 2 CIPN at weeks 3–11 (median: week 8) and began acupuncture treatment, on average, 5.5 weeks after cryotherapy initiation. All patients who initiated cryotherapy did so prior to developing grade 2 CIPN and starting acupuncture.

Patients received a median of three acupuncture treatments (quartiles 2, 5), with a range of one to 11 acupuncture treatments. Acupuncture was safe, and tolerable; the only toxicity of note was that four of 27 (15%) patients reporting mild bruising.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first risk-based CIPN prevention trial to study the effects of an intervention on patients who have developed moderate CIPN during chemotherapy. In this study, the majority had no or mild CIPN during weekly paclitaxel chemotherapy and did not require an intervention, suggesting that future CIPN prevention trials should focus on high-risk patients rather than on all patients receiving neurotoxic chemotherapy. Furthermore, acupuncture treatment was well tolerated with minimal toxicity.

Our results are favorable when compared to the historical control listed in E1199.23 In addition, our study showed that despite continuation of chemotherapy, those 27 patients’ CIPN symptoms stabilized with consistent FACT/GOG-Ntx and NPS scores, suggesting that acupuncture is associated with stabilization despite continuing chemotherapy. Since CIPN symptoms tend to be cumulative and dose-dependent,24–27 we are encouraged by these results; however, future RCTs of acupuncture against sham control are needed to determine its specific efficacy in CIPN prevention.

This study is the second acupuncture CIPN prevention trial to date. A recent study of electro-acupuncture (EA) for CIPN prevention showed that neither EA nor sham electro-acupuncture (SEA) prevented the worsening of FACT/GOG-Ntx from weeks 6 to 12 of chemotherapy.24 Our study differs from this study in two major ways. First, the timing of the intervention was different: the EA CIPN study treated everyone upfront; our study only provided the intervention to patients once they developed moderate CIPN symptoms. Second, the EA CIPN prevention trial used EA, while our study used manual acupuncture, which tends to cause less stimulation. This would suggest that further CIPN prevention studies should focus on high-risk patients and individualized interventions.

In our trial, two patients had chemotherapy delays due to CIPN and two patients had dose reduction due to CIPN. It is unlikely that the improvement and stabilization of all intervention phase patients’ CIPN symptoms were due to chemotherapy dose reduction or delay alone. Importantly, in the patients without any chemotherapy dose delay or reduction (n=23), CIPN grading stabilized and improved, suggesting acupuncture may also play a role in preventing chemotherapy dose reduction, delay, and early discontinuation due to CIPN.

While the underlying mechanism of acupuncture for CIPN is not completely understood, several animal studies have reported that acupuncture can stimulate Aδ and C nerve fibers, which can be damaged from chemotherapy causing CIPN symptoms.28–31 In a mouse model, acupuncture directly suppressed diffuse noxious inhibitory controls and led to activation of Aδ and C fibers and transmission in neurons of the spinal dorsal horn or trigeminal caudalis.32 Achievement of de qi sensation is a principal of acupuncture that serves as the indicator for minimal stimulation level in our study.33 Studies have suggested that Aδ and C fibers are involved during the de qi sensation and that the involvement of signal integration into the central nervous system may contribute to the effectiveness of acupuncture for CIPN.34

This study has a few limitations. It is a single arm trial without a control, and therefore, we cannot rule out a placebo effect or the possibility that the severity of CIPN plateaued at the end of chemotherapy, although multiples studies have shown that CIPN severity worsened with an increased dose of chemotherapy.24–27 In addition, cryotherapy may have also reduced CIPN severity and thus, we cannot rule out the potential efficacy from cryotherapy. However, our data shows that most of the patients who developed grade 2 CIPN did so while using cryotherapy, suggesting cryotherapy is unlikely to be fully effective in preventing the worsening of CIPN. The optimal duration and long-term effects of acupuncture on CIPN remain unknown. Lastly, the combination of cryotherapy, and chemotherapy reduction and delay together may overestimate the net effect of acupuncture. A randomized controlled trial is needed to address these limitations.

As one of the first risk-based prevention studies of acupuncture for patients with moderate CIPN, our study found that weekly acupuncture is associated with low rates of grade 3 CIPN and stabilization of CIPN symptoms. It shows promise for preliminary efficacy. A randomized controlled trial of acupuncture versus placebo is warranted to determine if acupuncture is effective in mitigating CIPN.

Highlights.

36% of screened patients developed grade 2 CIPN.

Only 1 of 27 patients in the intervention phase developed grade 3 CIPN.

Only 1 patient developed grade 3 CIPN, so acupuncture was worthy of further study.

Acupuncture was well tolerated, with 15% of patients reporting mild bruising.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [R21CA173263, Bao and R01CA158243, Mao]; a Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center P30 grant [P30-CA008748]; and the Byrne Fund and the Translational Research and Integrative Medicine Fund, both at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Victoria S. Blinder has a consulting/advisory role with The Anthem Foundation and Pfizer. Linda T. Vahdat has a consulting/advisory role with Berg Pharma and is also part of the speakers’ bureau for Eisai. Her institution has a patent pending on an application for BMD progenitor cells, and receives research funding from Celldex, Polyphor, Clovis Oncology, Immunomedics, AstraZeneca, PharmaMar, Abbvie, Galena Biopharma, Optimer Biotechnology, and Millennium. Maura N. Dickler has a consulting/advisory role with AstraZeneca, Novartis, Merrimack, Syndax, Genentech/Roche, Pfizer, TapImmune Inc., Puma Biotechnology, Lilly, Hengrui Pharmaceutical, and Celldex. Her institution receives research funding from Novartis, Lilly, and Genentech/Roche. Mark E. Robson has a consulting/advisory role with McKesson and AstraZeneca. He also discloses travel/accommodations/expenses and honoraria from AstraZeneca. His institution receives research funding from AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Medivation, Myriad Genetics, and InVitae.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pachman DR, Barton DL, Watson JC, et al. : Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: prevention and treatment. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 90:377–87, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JJ, Swain SM: Peripheral neuropathy induced by microtubule- stabilizing agents. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 24:1633–42, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akiko Hanai HI, Takashi Sozu, Moe Tsuda, Ikuko Yano, Takayuki Nakagawa, Satoshi Imai, Yoko Hamabe, Masakazu Toi, Hidenori Arai, Tadao Tsuboyama : Effects of Cryotherapy on Objective and Subjective Symptoms of Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathy: Prospective Self-Controlled Trial. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 110, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadakia KC, Rozell SA, Butala AA, et al. : Supportive cryotherapy: a review from head to toe. J Pain Symptom Manage 47:1100–15, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al. : Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 32:1941–67, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.C T: Mechanism of acupuncture analgesia based on animal experiments., in Pomerantz B SG, eds. (ed): Scientific Bases of Acupuncture. Berlin, Germany, Springer-Verlag, 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee BY LP, Newberg AB.: Acupuncture in theory and practice. Hospital Physician. 40:11–18, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abuaisha BB, Costanzi JB, Boulton AJ: Acupuncture for the treatment of chronic painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy: a long-term study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 39:115–21, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang C, Ma YX, Yan Y: Clinical effects of acupuncture for diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Tradit Chin Med 30:13–4, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao JL, Li ZR: [Clinical observation on mild-warm moxibustion for treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 28:13–6, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahn AC, Bennani T, Freeman R, et al. : Two styles of acupuncture for treating painful diabetic neuropathy--a pilot randomised control trial. Acupunct Med 25:11–7, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao HL, Gao X, Gao YB: [Clinical observation on effect of acupuncture in treating diabetic peripheral neuropathy]. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 27:312–4, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang H, Shi K, Li X, et al. : Clinical study on the wrist-ankle acupuncture treatment for 30 cases of diabetic peripheral neuritis. J Tradit Chin Med 26:8–12, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips KD, Skelton WD, Hand GA: Effect of acupuncture administered in a group setting on pain and subjective peripheral neuropathy in persons with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Altern Complement Med 10:449–55, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galantino ML, Eke-Okoro ST, Findley TW, et al. : Use of noninvasive electroacupuncture for the treatment of HIV-related peripheral neuropathy: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med 5:135–42, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroder S, Liepert J, Remppis A, et al. : Acupuncture treatment improves nerve conduction in peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurol 14:276–81, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minton O, Higginson IJ: Electroacupuncture as an adjunctive treatment to control neuropathic pain in patients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 33:115–7, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alimi D, Rubino C, Pichard-Leandri E, et al. : Analgesic effect of auricular acupuncture for cancer pain: a randomized, blinded, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 21:4120–6, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao T PN, Primrose J, Goloubeva O, Hester L, Wang L, Sadowska M, Lapidus R, Medeiros M, Lao L, Dorsey S, Badros A: A Pilot Study of Acupuncture in Treating Bortezomib-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy in Multiple Myeloma Patients. Integrative Cancer Therapies in press, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong R, Sagar S: Acupuncture treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy--a case series. Acupunct Med 24:87–91, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galer BS, Jensen MP: Development and preliminary validation of a pain measure specific to neuropathic pain: the Neuropathic Pain Scale. Neurology 48:332–8, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen MP, Friedman M, Bonzo D, et al. : The validity of the neuropathic pain scale for assessing diabetic neuropathic pain in a clinical trial. Clin J Pain 22:97–103, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sparano JA, Wang M, Martino S, et al. : Weekly paclitaxel in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 358:1663–71, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenlee H, Crew KD, Capodice J, et al. : Randomized sham-controlled pilot trial of weekly electro-acupuncture for the prevention of taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy in women with early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 156:453–464, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seidman AD, Hudis CA, Albanell J, et al. : Dose-dense therapy with weekly 1-hour paclitaxel infusions in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 16:3353–61, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith RE, Brown AM, Mamounas EP, et al. : Randomized trial of 3-hour versus 24-hour infusion of high-dose paclitaxel in patients with metastatic or locally advanced breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol B-26. J Clin Oncol 17:3403–11, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JJ, Swain SM: Peripheral neuropathy induced by microtubule- stabilizing agents. J Clin Oncol 24:1633–42, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao X, Qin Q, Yu X, et al. : Acupuncture at heterotopic acupoints facilitates distal colonic motility via activating M3 receptors and somatic afferent C- fibers in normal, constipated, or diarrhoeic rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil 27:1817–30, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang F, Wu L, Zhao J, et al. : Neurobiological Mechanism of Acupuncture for Relieving Visceral Pain of Gastrointestinal Origin . Gastroenterol Res Pract 2017:5687496, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tavee J, Zhou L: Small fiber neuropathy: A burning problem. Cleve Clin J Med 76:297–305, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voortman M, Fritz D, Vogels OJM, et al. : Small fiber neuropathy: a disabling and underrecognized syndrome. Curr Opin Pulm Med 23:447–457, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murase K, Kawakita K: Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in antinociception produced by acupuncture and moxibustion on trigeminal caudalis neurons in rats. Jpn J Physiol 50:133–40, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao JJ, Farrar JT, Armstrong K, et al. : De qi: Chinese acupuncture patients’ experiences and beliefs regarding acupuncture needling sensation--an exploratory survey. Acupunct Med 25:158–65, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou W, Benharash P: Significance of “Deqi” Response in Acupuncture Treatment: Myth or Reality. Joumal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies 7:186–189 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]