Abstract

This paper explores our efforts to support the expansion of a regional electronic consultation (eConsult) service on a national level by addressing potential policy barriers. We used an integrated knowledge translation (IKT) strategy based on five key activities leading to a National eConsult Policy Think Tank meeting: (1) identifying potential policy enablers and barriers; (2) engaging national and provincial/territorial partners; (3) including patient voices; (4) undertaking co-design and planning; and (5) adopting a solution-based approach. We successfully leveraged a diverse set of stakeholders in strategic discussions, culminating in actionable suggestions for next steps, which will serve to inform a national implementation strategy.

Abstract

Cet article étudie les efforts déployés pour soutenir l'application à l'échelle nationale d'un service régional de consultation électronique (eConsultation), et ce, en abordant d'éventuels obstacles d'ordre politique. Nous avons employé une stratégie d'ACI fondée sur cinq activités clés qui ont nourri les discussions d'un groupe de réflexion national sur l'eConsultation: (1) repérer les obstacles et facteurs favorables d'ordre politique, (2) mobiliser les partenaires nationaux, provinciaux et territoriaux, (3) inclure le point de vue des patients, (4) s'engager dans la conception et la planification et (5) adopter une démarche axée sur les solutions. Nous avons réussi à impliquer un ensemble diversifié de partenaires dans les discussions stratégiques, ce qui a mené à la formulation de suggestions pratiques pour les prochaines étapes, lesquelles serviront à éclairer la stratégie de mise en œuvre nationale.

Introduction

Canada has been described as the land of perpetual pilot projects (Bégin et al. 2009; Naylor et al. 2015). Despite significant investments (Naylor et al. 2015), many pilots are unable to expand beyond a local level, causing valuable knowledge to remain siloed and unable to improve healthcare on a broader scale. An advisory panel convened by the Canadian government has attributed this trend to the lack of any dedicated funding or mechanism to drive systemic innovation, and the fragmented nature of the system itself, with separate budgets and accountabilities for different provider groups and sectors (Naylor et al. 2015). In addition, the broader research community often fails to actively engage in knowledge translation beyond traditional passive dissemination through journal publications. Consequently, policy issues are often cited as insurmountable barriers for scale-up and spread of healthcare innovations, particularly those based on implementation of technology.

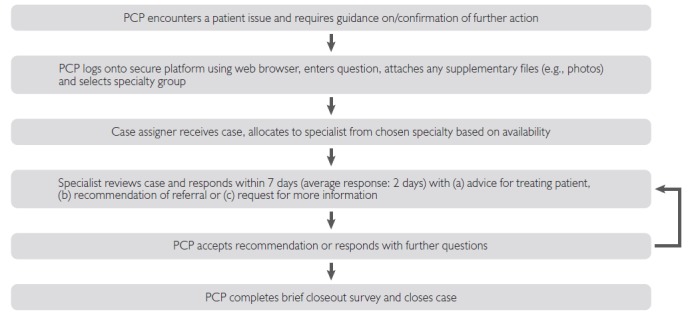

In 2010, our team developed the Champlain BASE™ (Building Access to Specialists through eConsultation) eConsult service, a model of asynchronous provider to provider communication whereby primary care providers (PCPs) and specialists communicate through the use of a secure web-based platform (Figure 1). The eConsult service began as a proof-of-concept in the Champlain Local Health Integration Network (LHIN), one of 14 health regions responsible for planning, integrating, and funding local healthcare in Ontario. Numerous studies have reported that the service reduced wait times for specialist advice (Keely et al. 2013), helped avoid unnecessary referrals (Keely et al. 2013), lowered costs (Liddy et al. 2016) and received high levels of satisfaction from patients and providers alike (Keely et al. 2013; Liddy et al. 2015a).

Figure 1.

Diagram of the Champlain BASE™ eConsult service

BASE = Building Access to Specialists through eConsultation; PCP = primary care provider.

Given eConsult's success on a regional level, we realized that the service had the potential to improve patient, provider, and health system experiences for people across Canada. However, an examination of existing policies guided by our past implementation experience identified three policy areas that could deter eConsult's expansion to new provinces: privacy, financing, and delivery of services (Liddy et al. 2015a). The research team questioned how we could translate these challenges into a meaningful dialogue that could lead to a more favourable policy context for the scale and spread of eConsult in Canada.

The challenges of translating innovations into practice have been widely recognized and innovators have taken steps to overcome them. In their widely respected ‘knowledge to action’ framework, Graham and colleagues discuss the “know–do gap” separating research from actionable policy and highlight ways it can be successfully bridged (Graham and Tetroe 2009; Graham and Tetroe 2007; Graham et al. 2006). The framework describes the process of integration of knowledge creation with its application and emphasizes engagement of knowledge users – including policy makers – in this process. However, it does not move beyond this to describe the “how to” required to succeed.

Building on the work of Graham and colleagues, this paper describes the integrated knowledge translation (IKT) approach our research team took to identify policy issues affecting the spread and scale-up of the Champlain BASE™ eConsult service. IKT has been described and promoted by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR 2012) and requires researchers and knowledge user stakeholder groups to develop partnerships and engage in a collaborative process, with the overarching goal being the co-production of knowledge, its exchange and its translation into action. While advocated as an approach for enhancing the relevance of research and facilitating its use, IKT has also been described as challenging and inconsistently applied. Despite the fact that the enablers, barriers, and conditions that have been reported to influence the IKT have been studied and described, their associations with relevant outcomes and contextual factors affecting these outcomes remain largely unknown (Gagliardi et al. 2015). In order to add clarity to the process, we have tailored the IKT approach to our needs by grounding it in a practical step-wise process we used when first establishing the eConsult service (Liddy et al. 2013). We discuss how a research team working together with interested partners and stakeholders, including patients, created a collaborative space to (1) identify critical enablers and opportunities/challenges, (2) articulate a policy agenda, and (3) define strategies intended to influence policy discussions and decisions in support of spread and scale-up of an eConsult service.

This paper will be of interest to those who are working in health system research and desire to identify strategies for scaled implementation, and will provide practical approaches to engaging stakeholders in deliberative policy dialogue to support the spread and scale-up of healthcare innovations in Canada.

An IKT Approach to Shaping Policy

We assembled a collaborative, multidisciplinary team of researchers, healthcare providers, decision-makers, and patient advisors from across Canada. The team then met for a National eConsult Policy Think Tank (hereafter referred to as ‘the Think Tank’) held in Ottawa, Ontario, on December 5, 2016, to solicit a range of viewpoints on the policy issues affecting widespread dissemination and scale-up of eConsult.

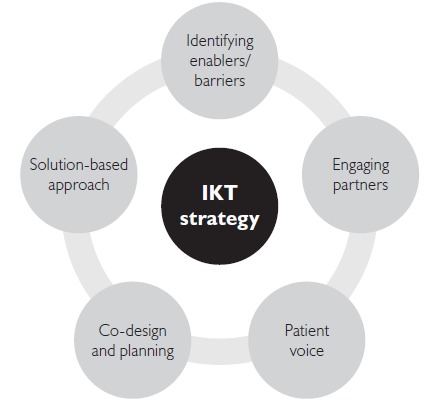

To plan and implement this event, we engaged in five key activities that underpinned our IKT strategy: (1) identifying potential policy enablers and barriers; (2) engaging national and provincial/territorial partners; (3) including patient voices; (4) undertaking co-design and planning; and (5) adopting a solution-based approach. A model of our strategy is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The IKT strategy undertaken by Champlain BASE™ team

BASE = Building Access to Specialists through eConsultation; IKT = integrated knowledge translation.

1. Identifying potential policy enablers and barriers

First and foremost, we identified the importance of proactively including policy aspects within our research work, which included identifying areas of policy that could act as potential enablers or barriers to scale-up. In a previous paper examining policy factors influencing eConsult, we identified three policy challenges which could deter the wide-scale implementation of an eConsult service: privacy concerns, lack of standard payment models, and ambiguity of roles for service delivery (Liddy et al. 2015a). For these particular areas of focus, our conclusions were that (1) concerns over privacy remain a barrier to the adoption of electronic platforms or innovations among healthcare providers, (2) standard payment models may not be applicable to eConsult, and (3) ambiguities in the specialist's role could create challenges in the service's expansion (Liddy et al. 2015a). Using these concepts as a foundation, we formulated key focus areas for discussion, modifying our initial conclusions to fit the current context. Notably, issues of privacy were not explicitly discussed in our Think Tank, whereas our exploration of policy challenges relating to delivery of services brought up issues of equity (i.e., how to ensure patients get equitable care regardless of jurisdiction or remoteness) and standards (i.e., how specialists are chosen and evaluated), which evolved into two distinct categories. The three chosen areas of focus were thus: (1) delivery of service and standards, (2) payment, and (3) equitable access.

2. Engaging national and provincial/territorial partners

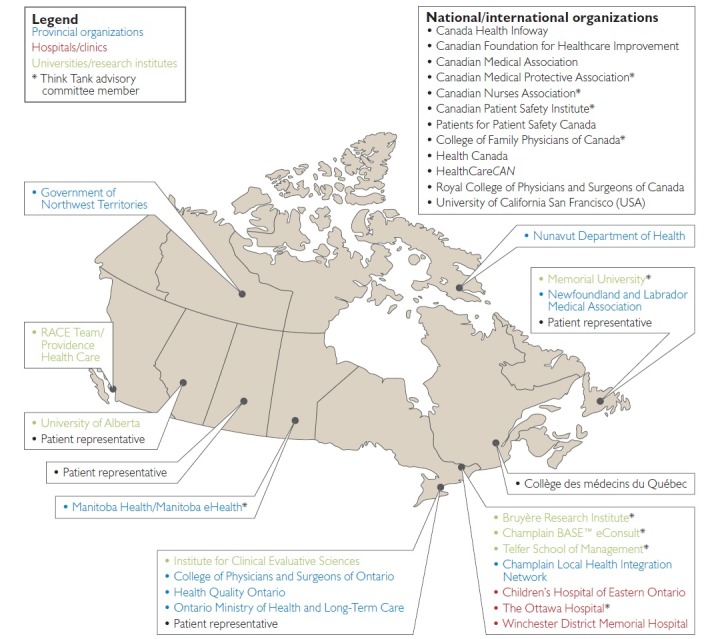

Successful IKT requires active and continuous collaboration between researchers and knowledge end-users such as policy makers, healthcare providers, and patients (CIHR 2012). End-users are defined as individuals who are likely to be able to use research results to make informed decisions about health policies, programs and/or practices. Given our intention to scale-up and spread eConsult from a regional to a national level, we engaged a range of stakeholders including representatives from provincial and territorial governments, national organizations, healthcare providers, researchers, and patients to ensure a sufficient breadth of perspectives and experiences. Participants included representation from 11 national organizations, three provincial organizations, and a delegate from the US, as well as five patient advisors. The Canadian Medical Protective Association, a not-for-profit organization representing physicians across Canada, agreed to co-host the Think Tank. Of the 101 invited individuals, 47 participants attended the Think Tank. Thirteen per cent of attendees self-identified as government representatives, 13% as patients and 6% as healthcare providers. The majority represented national organizations (31%) and research institutes (31%). Participant distribution is outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Map of institutions and organizations represented at the 2016 Think Tank

BASE = Building Access to Specialists through eConsultation; RACE = Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise.

3. Including patient voices

Patient input is a critical component of any healthcare innovation. Patient involvement in health policy, clinical care, and research has gained significant momentum recently along with the idea that no policy should be reached without full participation of patients as stakeholders (CIHR 2018). To ensure patients' voices were included in the conversation, we partnered with the Canadian Patient Safety Institute, which engaged with its Patients for Patients Safety Canada volunteer network to recruit interested patient advisors from four provinces: Alberta (AB), Saskatchewan (SK), Ontario (ON), and Newfoundland and Labrador (NL). Patients actively participated in discussions, providing their invaluable perspective on how meaningful policies could ensure that eConsult continues to deliver high-quality patient-centred care.

4. Undertaking co-design and planning

In preparation for the Think Tank, we formed a pan-Canadian advisory committee consisting of 10 volunteer partners and collaborators. Members included representatives from four national organizations and academic/provincial institutions across three provinces (ON, Manitoba [MB] and NL), all of whom had previously supported funding applications and projects related to eConsult. The group met three times by teleconference to (1) develop the Think Tank agenda, (2) design the meeting format, and (3) establish strategies for ensuring representation of key stakeholder groups (i.e., healthcare providers, decision-makers and patient advisors). Discussion of the latter point included an emphasis on co-design between stakeholder groups, with a particular focus on promptly engaging decision-makers and ensuring they were empowered in their role and contributions as a central part of the development process – changing their role from “guest” to “member of the research family.”

5. Adopting a solution-based approach

To address issues in detail, participants broke into working groups based around one of the three areas of focus: delivery of service and standards, payment, and equitable access. Participants could choose to join a group on any of these topics, where they brainstormed answers to the following questions:

What are existing policies that could support and enable the spread/scale-up of eConsult?

What are your key recommendations?

Who else needs to be involved in the conversation to ensure success?

Following the small group discussion sessions, participants gathered for an afternoon plenary session where a representative from each working group presented each of the small groups' findings. Audience members asked questions and engaged the group in a dialogue on the chosen topic. Patient representatives were asked to offer their reflections on the day and recommendations for the next steps necessary to enable expansion of the eConsult service. To ensure a solution-based approach, the meeting concluded with a plan for next steps in reaching specific decision-makers on a national level and presenting them with actionable briefing notes from the Think Tank.

After the Think Tank, certain gaps were noted and additional jurisdiction-specific information was requested from the participants electronically as follows:

What are the existing interjurisdictional agreements in each Canadian province/territory?

What are the current cross-provincial/territorial referral patterns?

Who are other key organizations that should be involved?

Results/Next Steps/Follow-Up Activities

Following the Think Tank, all stakeholders continued working together to synthesize and consolidate relevant, actionable solutions to identified policy gaps. Participants in the Think Tank have met via teleconference on a quarterly basis in order to follow up on outstanding items and discuss next steps for policy implementation. Additionally, several team members volunteered to join working groups, which meet regularly outside of the quarterly teleconferences in order to contribute to ongoing policy projects, including (1) an in-depth qualitative analysis of the breakout discussions that took place during the Think Tank, and (2) the development of policy briefing notes.

Several themes have emerged from the working groups' analysis, which speak to the key factors in supporting eConsult's expansion: maintaining patient-centredness, emphasizing its value for patients, ensuring effective regulation, and supporting implementation. The importance of keeping patients at the centre of the process cut across themes, a point neatly encapsulated by one participant, who described the question that should be at the centre of any implementation decision: “When [patients] look at the eConsult service, what is going to make them say ‘yes, this is an equitable service’? What is it that patients are going to want to see?” Through the working groups, participants have offered great insight into the IKT process, highlighting barriers and enablers and developing recommendations for action. Furthermore, participants' willingness to engage in regular meetings and support additional studies speaks to their investment in eConsult, which is a critical factor to the overall success of the service's expansion.

Building on our analyses, we developed a series of briefing notes that provide guidance on the development of policies in five key areas: payment for providers, interjurisdictional licensing, patient privacy, quality assurance, and regulation (See Appendix 1). Their content was drawn from the analyses discussed in this paper, and further refined through input from our national partners. We held a follow-up meeting to the Think Tank, called the National Forum, in December of 2017, where 54 participants from across Canada engaged in tabletop sessions to workshop the policy briefs, identify gaps, and ensure they captured the best possible information and recommendations for action. Furthermore, our partners have assisted in this effort by generating their own statements. For instance, the Canadian Medical Protective Association has recently released a detailed statement about the use of eConsult services and outlining physicians' legal, ethical, and professional obligations when using them to provide care (Canadian Medical Protective Association 2017). Further discussion of policy issues will take place at our third event, to be held in November 2018.

Discussion

We have outlined an IKT approach that informed a process for exploring policy gaps affecting eConsult's scale-up from a regional to a national level, resulting in a series of thoughtful, relevant, and actionable recommendations for next steps. Our approach centres on the researcher's role, which includes identifying policy enablers and barriers, establishing partnerships capable of enacting supportive policy, coordinating discussion with key stakeholders from different groups (including patients), and linking the results of these activities to generate solutions. In this way, the researcher plays a much more extensive role in the translation and uptake of research findings that could transform and support healthcare improvement in Canada. This approach was effective at transferring knowledge into actionable policy recommendations and helped us to create a growing group of engaged individuals from across Canada, who continue to work together on the spread and scale of eConsult, and, through their enthusiasm, have made the Think Tank into an annual event due to host its third iteration in 2018.

We positioned our paper on the central tenet that policy barriers are among the most common factors impeding the translation of knowledge into action (Graham and Tetroe 2007). Informing and influencing policy requires a different approach than the traditional academic one (Clancy et al. 2012) as only legislators can remove the barriers to healthcare innovation stemming from current laws and regulations (Herzlinger 2006). In her work examining how policy makers use health service research, Marsha Gold revealed that healthcare policy makers' decisions to implement research programs are influenced by “underlying politics” (Gold 2009). To influence policy decisions, researchers must develop a deeper understanding of the context in which these decisions are made (Blendon and SteelFisher 2009). This includes being aware of existing healthcare policies, how evidence-informed public policy is developed, and which research topics have policy leverage, and presenting these factors in a way that engages policy makers' interests. By actively engaging in policy discussions and ensuring engagement of the knowledge users as per IKT approach, researchers could support better adoption and implementation of promising innovations (Graham and Tetroe 2007; Graham et al. 2006; Graham and Tetroe 2009).

It is worth noting that some policy barriers are not based on prohibitive legislation but instead on users' perceptions. An example of this involves the various provincial privacy legislations, such as the Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) in Ontario, which are designed to protect patients' privacy when interacting with the healthcare system. While PHIPA does restrict some forms of online communication, such as e-mails between patients and providers (Canadian Medical Protective Association 2005), there are other PHIPA compliant online communication technologies, such as eConsult, which can offer greater access without sacrificing privacy (Liddy et al. 2015b). Nonetheless, confusion over PHIPA's scope can prevent some providers from engaging with electronic innovations, despite the fact said innovations are fully permitted under current legislation. This illustrates how aggressive and inflexible policies can raise unintended barriers to innovation.

Our IKT approach had some limitations. Although we made a conscious effort to invite a diverse range of stakeholders, we were unable to engage some key parties. The distribution of organizations participating in the meeting may have influenced the established recommendations. Notably, we did not have any participants with the knowledge or decision-making authority to describe the existing agreements governing interjurisdictional referrals. Recognizing the limits to our own reach as researchers, we could, and should, leverage the networks of our stakeholders. To this end, we invited all working groups to share a list of stakeholders who should be involved in subsequent discussions, with the aim of obtaining a broader and more inclusive perspective. Furthermore, limiting the meeting to one day prevented an exhaustive discussion of all topics.

Conclusion

Using an IKT approach, we leveraged a diverse set of stakeholders in strategic discussions following the identification of specific policy gaps. These stakeholders represented seven provinces/territories (plus one delegate from the US) and engaged in a valuable discussion on healthcare policy recommendations to support the expansion of the eConsult service across Canada. Participants provided thoughtful guidance and helped define actionable suggestions for next steps, which will serve to support decision-makers in developing a national implementation strategy. This paper will be of interest for those who are working in health system research and its implementation and will provide some practical approaches on engaging stakeholders in deliberative policy dialogue and, most importantly, on influencing policy change that will improve healthcare service delivery, and ultimately, patient experiences and health outcomes.

Contributor Information

Clare Liddy, Clinician Investigator, C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre, Bruyère Research Institute, Ottawa, ON.

Isabella Moroz, Research Associate, C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre, Bruyère Research Institute, Ottawa, ON.

Justin Joschko, Research Coordinator, C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre, Bruyère Research Institute, Ottawa, ON.

Tanya Horsley, Associate Director, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Craig Kuziemsky, Full Professor, Telfer School of Management, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON.

Katharina Kovacs Burns, Senior Manager, Alberta Health Services, Edmonton, AB.

Sandi Kossey, Senior Director, Canadian Patient Safety Institute, Edmonton, AB.

Gunita Mitera, Director, Program and Practice Support, College of Family Physicians Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Erin Keely, Chief, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON.

References

- Bégin H.M., Eggertson L., Macdonald N. 2009. “A Country of Perpetual Pilot Projects.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 180(12): 1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendon R.J., SteelFisher G.K. 2009. “Commentary: Understanding the Underlying Politics of Health Care Policy Decision Making.” Health Services Research 44(4): 1137–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). 2012. Guide to Knowledge Translation Planning at CIHR: Integrated and End-of-grant Approaches. Ottawa, ON: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). 2018. Canada's Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research - Patient Engagement Framework at a Glance. Retrieved June 12, 2018. <http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/49232.html>.

- Canadian Medical Protective Association. 2005. Using Email Communication with Your Patients: Legal Risks. Retrieved July 13, 2017. <www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/advice-publications/browse-articles/2005/using-email-communication-with-your-patients-legal-risks>.

- Canadian Medical Protective Association. 2017. Is that eConsultation or eReferral Service Right for Your Medical Practice? Retrieved October 3, 2017. <https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/advice-publications/browse-articles/2017/is-that-econsultation-or-ereferral-service-right-for-your-medical-practice>.

- Clancy C.M., Glied S.A., Lurie N. 2012. “From Research to Health Policy Impact.” Health Services Research 47(1pt2): 337–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi A.R., Berta W., Kothari A., Boyko J., Urquhart R. 2015. “Integrated Knowledge Translation (IKT) in Health Care: A Scoping Review.” Implementation Science 11: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold M. 2009. “Pathways to the Use of Health Services Research in Policy.” Health Services Research 44(4): 1111–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham I. D., Tetroe J. 2007. “How to Translate Health Research Knowledge into Effective Healthcare Action.” Healthcare Quarterly 10(3): 20–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham I. D., Logan J., Harrison M. B., Straus S. E., Tetroe J., Caswell J., W. et al. 2006. “Lost in Knowledge Translation: Time for a Map?” Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 26(1): 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham I. D., Tetroe J. M. 2009. “Getting Evidence into Policy and Practice: Perspective of a Health Research Funder.” Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 18(1): 46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzlinger R. 2006. “Why Innovation in Health Care Is So Hard.” Harvard Business Review 84(5): 58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keely E., Liddy C., Afkham A. 2013. “Utilization, Benefits, and Impact of an e-Consultation Service Across Diverse Specialties and Primary Care Providers.” Telemedicine Journal and e-Health 19(10): 733–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddy C., Afkham A., Drosinis P., Joschko J., Keely E. 2015a. “Impact and Satisfaction with a New eConsult Service: A Mixed Methods Study of Primary Care Providers.” Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 28(3): 394–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddy C., Drosinis P., Deri C., Armstrong F., McKellips Afkham A., Keely E. 2016. “What Are the Cost Savings Associated with Providing Access to Specialist Care Through the Champlain BASE eConsult Service? A Costing Evaluation.” BMJ Open 6(6): e010920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddy C., Maranger J., Afkham A., Keely E. 2013. “Ten Steps to Establishing an e-Consultation Service to Improve Access to Specialist Care.” Telemedicine Journal and e-Health 19: 982–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddy C., Joschko J., Keely E. 2015b. “Policy Innovation is Needed to Match Health Care Delivery Reform: The Story of the Champlain BASE eConsult Service.” Health Reform Observer 3(2): 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor D., Girard F., Mintz J. M., Fraser N., Jenkins T., Power C. et al. 2015. Unleashing Innovation: Excellent Healthcare for Canada: Report of the Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada. [Google Scholar]