Abstract

Background

Medical end-of-life decisions (MELD) and shared decision-making are increasingly important issues for a majority of persons at the end of life. Little is known, however, about the impact of physician characteristics on these practices. We aimed at investigating whether MELDs depend on physician characteristics when controlling for patient characteristics and place of death.

Methods and findings

Using a random sample (N = 8,963) of all deaths aged 1 year or older registered in Switzerland between 7 August 2013 and 5 February 2014, questionnaires covering MELD details and physicians' demographics, life stance and medical formation were sent to certifying physicians. The response rate was 59.4% (N = 5,328). Determinants of MELDs were analyzed in binary and multinomial logistic regression models. MELDs discussed with the patient or relatives were a secondary outcome. A total of 3,391 non-sudden nor completely unexpected deaths were used, 83% of which were preceded by forgoing treatment(s) and/or intensified alleviation of pain/symptoms intending or taking into account shortening of life. International medical graduates reported forgoing treatment less often, either alone (RRR = 0.30; 95% CI: 0.21–0.41) or combined with the intensified alleviation of pain and symptoms (RRR = 0.44; 0.34–0.55). The latter was also more prevalent among physicians who graduated in 2000 or later (RRR = 1.60; 1.17–2.19). MELDs were generally less frequent among physicians with a religious affiliation. Shared-decision making was analyzed among 2,542 decedents. MELDs were discussed with patient or relatives less frequently when physicians graduated abroad (OR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.50–0.87) and more frequently when physicians graduated more recently; physician's sex and religion had no impact.

Conclusions

Physicians' characteristics, including the country of medical education and time since graduation had a significant effect on the likelihood of an MELD and of shared decision-making. These findings call for additional efforts in physicians' education and training concerning end-of-life practices and improved communication skills.

Introduction

Compared to other countries, an exceptionally high percentage of deaths in Switzerland is preceded by a decision to forgo life-prolonging treatments [1–3], contributing to a high overall prevalence of medical end-of-life decisions (MELDs). These differences between Switzerland and other countries may be explained by what Gysels et al. called "evidence for clearly distinguishable national cultures of end-of-life care, with differences in meaning, priorities, and expertise in each country" [4]. In addition to such cultural factors, previous research has also shown that certain groups of patients are more likely to experience death preceded by an MELD, particularly people who die of cancer and older people [5,6] and that there are differences in the type of MELD by patient’s sex and age [6–8]. Likewise, the involvement of patients or relatives in the decision-making process has been shown to be influenced by cultural and patient-related factors, such as age [8–10].

There are several ways in which also a physician’s characteristics could affect medical end-of-life decision-making and the discussion of these decisions with patients or relatives. However, a 2011 systematic review of the literature on patient and healthcare professional factors influencing end-of-life decision-making concluded that only a few studies examined the influence of physician-specific factors and those that did often focused on decision-making in hospital or acute care units only [11]. In Belgium MELDs were more frequent among physicians having received a postgraduate training in palliative or terminal care and among those having attended a non-Catholic university [6]. Younger physicians have also been reported to involve patients more often in discussions around MELDs [6,9]. Most studies, however, only assessed attitudes or evaluated hypothetical patients. In a U.S. study, Catholic physicians had significantly more objections to the withdrawal of life support than their Protestant peers [12] and in an international study, physicians with specific religious affiliations showed less willingness than non-religious physicians to administer drugs explicitly intending to hasten patient's death [13]. There is evidence that physician’s sex has an important impact on the time spent on communication [14] and on health outcomes [15]. Female physicians were reported to be less supportive than male physicians towards ending of life without explicit request, more supportive of intensified alleviation of pain and symptoms with possible life-shortening effect [16]. There is evidence that female physicians are more likely to engage in patient-centered communication [14], an important precondition for shared decision-making. Quite unsurprisingly, health outcomes also vary by physician's years of practice [17,18].

Cultural or country-specific factors could also influence the training and education of physicians. Depending on where a physician was trained, there may be not only variation regarding outcomes [17], but also whether a physician is more or less likely to make an MELD. Such cultural influence may also affect the likelihood of a physician involving patients and relatives in a discussion about MELDs. A study on end-of-life decision-making in an Israeli intensive care unit found that whether physicians had trained in America or in Eastern Europe had a large impact on how often they discussed forgoing life-sustaining treatments with patients [19]. Further evidence for the potential impact of physician’s characteristics on shared decision-making came from a systematic review that found that one of the biggest facilitators for shared-decision making was the motivation of health professionals and their view that shared-decision making would lead to better patient outcomes [20].

The lack of knowledge surrounding how physician’s characteristics impact real decision-making at the end of life–both the types of decision made as the involvement of others in this decision–makes it hard to address potential inequalities in decision-making, and to ensure shared decision-making is a priority in all end-of-life situations. With this study we aim to assess the impact of physician-related determinants of MELDs and patient involvement in these decisions. There are two specific research questions. First: Do physician characteristics have an impact on the likelihood of an MELD when controlling for both patient and setting characteristics? Second, do physician characteristics–in case an MELD took place–have an impact on the likelihood of patient and/or relatives being involved in shared decision-making when controlling for both the patient and setting characteristics?

Methods

Data collection

We conducted a mortality follow-back study on a continuous random sample of death registrations in Switzerland between August 7, 2013 and February 5, 2014, from which we obtained from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office the address of the certifying physician. The sample represented 21.3% of deaths among those aged 1 year or older in the German-, 41.1% in the French- and 62.9% in the Italian-speaking regions of Switzerland [21]. In total, 8,963 questionnaires were mailed in a strictly anonymous setting to the certifying physicians, of which 5,328 (59.4%) were returned until June 11, 2014.

Measures

Using an internationally standardized questionnaire [5] (online English version: [22]), physicians were asked whether they had: (1) withheld or withdrawn a probably life-prolonging medical treatment taking into account the possibility of hastening the patient’s death or explicitly intending to hasten the patient's death or not to prolong their life; (2) intensified the alleviation of pain and/or symptoms (APS) with drugs taking into account or partly intending hastening the patient's death; or (3) prescribed or administered a drug with the explicit intention of ending the patient's life. For all these cases it was also assessed whether the patient ever expressed a wish for hastening death or for applying all life-prolonging measures, and whether the MELD was discussed with the patient or other persons (relatives, other physicians, healthcare professionals, any other person). Continuous deep sedation was assessed separately, but no questions were asked about the decision-making process so it is not included in this paper.

The region was defined by the language of the death certificate and place of death was determined from the categories in the questionnaire (at home, retirement community, long-term care home, hospice or palliative unit, hospital, other place).

Patient characteristics were available from death certificates (sex, age, civil status, religious affiliation). Broad cause of death was assessed in the questionnaire, because the cause of death information was not yet available from this early version of the death certificates and–due to anonymization–could not be supplemented ex post. More details are given elsewhere [23].

The questionnaire also encompassed several questions about the attending physician, namely sex, year (before 1970, 1970–1984, 1985–1999, 2000 or later) and place of graduation (German-speaking Switzerland, French-speaking Switzerland, abroad), the number of deceased patients cared for in the preceding six months, palliative care education (yes/no), religion or life stance (catholic, protestant, other religion/philosophy, not religious) and importance of religion/life stance for making an MELD (very important, important, less important, not important).

Sample

We selected all patients who were permanent residents of Switzerland, did not die suddenly and completely unexpected or by assisted suicide, and had a first contact with the responding physician when still alive. Out of 5,328 returned questionnaires, 3,391 concerned deaths that fulfilled these criteria and had at least minimal information on place of death and important physician attributes (sex, place and year of graduation).

For the analysis of shared decision-making, deaths without preceding forgone treatment or APS (N = 619) or lacking all information regarding discussion as well as other expression of patient's preferences (N = 230) were excluded, leaving 2,542 decedents with forgone treatment and/or APS and information about shared-decision making.

Statistical analysis

An age-sex-region-specific weighting was applied to make the data representative of all deaths in the sample period. Weighted percentages were used to describe the data.

Multinomial logistic regression [24] was used to calculate relative risk ratios (RRR), 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P values of potential determinants of different MELD categories. Binary logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P values of potential determinants of any MELD vs. no MELD as well as of patient and family involvement in MELDs. All calculations were performed using Stata (version 13.1, StataCorp) statistical package.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was declared exempt from ethics review by the Zurich Cantonal Ethics Board (KEK-StV-Nr. 23/13). Participants were informed about the study in a cover letter. Questionnaire return was considered to imply consent to participate.

Results

Medical end-of-life decisions

Out of 3,391 eligible deaths, 2,772 (83%) were preceded by forgoing a life-prolonging treatment (17% of cases), intensified alleviation of pain and symptoms (APS; 12%) or both measures combined (54%; Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptives of the study population: Forgoing treatment(s)* and APS** in Switzerland 2013–2014 (N = 3,391).

| Forgoing* alone | Forgoing* & APS** | APS** alone | Neither forgoing nor APS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 535 (16.6%) | N = 1801 (53.9%) | N = 436 (12.3%) | N = 619 (17.2%) | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Patient’s characteristics | ||||||||

| Patient’s sex: Female | 286 | 16.7 | 961 | 53.8 | 253 | 13.3 | 308 | 16.2 |

| Male | 249 | 16.5 | 840 | 53.9 | 183 | 11.1 | 311 | 18.4 |

| Patient’s age: <65y | 59 | 15.4 | 222 | 56.7 | 45 | 11.2 | 72 | 16.7 |

| 65-79y | 130 | 15.3 | 469 | 54.4 | 102 | 11.6 | 166 | 18.7 |

| 80y and over | 346 | 17.3 | 1110 | 53.2 | 289 | 12.8 | 381 | 16.7 |

| Patient's nationality: Swiss | 494 | 16.8 | 1644 | 53.7 | 399 | 12.4 | 558 | 17.1 |

| Foreign | 41 | 14.3 | 157 | 55.9 | 37 | 11.5 | 61 | 18.3 |

| Patient's religion: Non-religious | 34 | 19.0 | 96 | 54.6 | 20 | 9.8 | 31 | 16.6 |

| Catholic | 218 | 16.5 | 729 | 53.8 | 184 | 12.6 | 246 | 17.1 |

| Protestant | 210 | 16.6 | 701 | 54.9 | 161 | 12.3 | 220 | 16.2 |

| Other† | 73 | 15.8 | 275 | 50.5 | 71 | 12.6 | 122 | 21.1 |

| Patient's civil status: Married | 212 | 16.9 | 720 | 54.6 | 171 | 12.0 | 237 | 16.5 |

| Single | 50 | 14.7 | 185 | 55.3 | 38 | 12.2 | 67 | 18.0 |

| Widowed | 229 | 17.5 | 720 | 53.4 | 191 | 12.9 | 232 | 16.2 |

| Divorced | 44 | 13.4 | 176 | 51.9 | 36 | 11.1 | 83 | 23.6 |

| Cause of death: CVD | 152 | 18.9 | 389 | 47.6 | 107 | 13.0 | 182 | 20.4 |

| Injury/unknown | 31 | 25.8 | 59 | 44.6 | 14 | 9.3 | 29 | 20.3 |

| Cancer | 104 | 10.7 | 617 | 58.0 | 158 | 13.5 | 203 | 17.8 |

| Other | 248 | 18.6 | 736 | 55.7 | 157 | 11.2 | 205 | 14.5 |

| Physician’s characteristics | ||||||||

| Physician’s sex: Female | 168 | 15.2 | 637 | 57.7 | 142 | 12.3 | 181 | 14.8 |

| Male | 367 | 17.3 | 1164 | 52.0 | 294 | 12.3 | 438 | 18.4 |

| Year of graduation: <1985 | 204 | 19.5 | 559 | 48.8 | 168 | 13.6 | 222 | 18.1 |

| 1985–1999 | 134 | 17.1 | 425 | 51.8 | 100 | 12.2 | 162 | 18.9 |

| ≥2000 | 197 | 14.0 | 817 | 59.2 | 168 | 11.3 | 235 | 15.5 |

| Place of graduation: Switzerland | 463 | 18.4 | 1442 | 54.9 | 315 | 15.9 | 431 | 15.3 |

| Outside of Switzerland | 72 | 9.8 | 359 | 50.1 | 121 | 11.3 | 188 | 24.2 |

| Physician's religion: Non-religious | 155 | 15.9 | 594 | 58.4 | 124 | 11.8 | 150 | 14.0 |

| Catholic | 150 | 14.7 | 565 | 52.3 | 157 | 13.6 | 227 | 19.2 |

| Protestant | 153 | 18.4 | 464 | 54.9 | 89 | 10.2 | 146 | 16.5 |

| Other† | 77 | 19.1 | 178 | 43.8 | 66 | 15.3 | 96 | 21.8 |

| Setting characteristics | ||||||||

| Place of death: Hospital‡ | 229 | 15.0 | 870 | 57.1 | 180 | 11.4 | 272 | 16.6 |

| Home setting/other§ | 132 | 18.5 | 382 | 47.6 | 119 | 13.7 | 174 | 20.1 |

| Long-term care home | 174 | 17.5 | 549 | 53.9 | 137 | 12.6 | 173 | 16.0 |

*: Withholding or withdrawing treatment

**: Intensified alleviation of pain and symptoms

†: Includes ‘no answer’

‡: Includes hospital and palliative care unit/hospice

§: Includes home, elderly care residence, and unspecified ‘other’

The estimated relative risk ratios (RRR) from a multinomial logistic regression model contrasting "forgoing alone", "APS alone" and "both measures combined" with "neither" as reference category are presented in Table 2, along with 95% confidence intervals. Patient's nationality and religion were dropped in the final model, because they did not contribute information.

Table 2. Patient and physician related determinants for medical end-of-life decisions: multinomial logistic regression with neither forgoing nor APS (N = 619) as reference category adjusted for cause of death, place of death, language region and patients' age.

| Forgoing* alone | Forgoing* & APS˚ | APS˚ alone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 535 | N = 1801 | N = 436 | ||||

| RRR (95% CI) | P-value | RRR (95% CI) | P-value | RRR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Patient’s characteristics | ||||||

| Sex: Female | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Male | 0.89 (0.69–1.15) | 0.38 | 0.87 (0.70–1.07) | 0.18 | 0.74 (0.56–0.97) | 0.03 |

| Civil status: Married | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Single | 0.72 (0.47–1.11) | 0.14 | 0.89 (0.64–1.25) | 0.51 | 0.82 (0.52–1.30) | 0.40 |

| Widowed | 0.94 (0.70–1.26) | 0.68 | 1.02 (0.80–1.29) | 0.90 | 0.98 (0.71–1.34) | 0.89 |

| Divorced | 0.56 (0.37–0.86) | <0.01 | 0.65 (0.47–0.89) | <0.01 | 0.59 (0.38–0.92) | 0.02 |

| Physician’s characteristics | ||||||

| Year of graduation <1985 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 1985–1999 | 0.90 (0.66–1.23) | 0.50 | 1.04 (0.81–1.34) | 0.76 | 0.85 (0.60–1.18) | 0.33 |

| ≥2000 | 0.98 (0.67–1.44) | 0.91 | 1.60 (1.17–2.19) | <0.01 | 0.98 (0.65–1.48) | 0.94 |

| Graduation: in Switzerland | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Outside of Switzerland | 0.30 (0.21–0.41) | <0.001 | 0.44 (0.34–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.62–1.17) | 0.33 |

| Sex: Female | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Male | 0.80 (0.60–1.06) | 0.12 | 0.80 (0.64–1.01) | 0.06 | 0.78 (0.57–1.05) | 0.10 |

| Religion: Non-religious | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Catholic | 0.71 (0.52–0.98) | 0.04 | 0.72 (0.56–0.92) | <0.01 | 0.85 (0.61–1.18) | 0.33 |

| Protestant | 0.88 (0.64–1.22) | 0.45 | 0.78 (0.60–1.01) | 0.06 | 0.70 (0.49–1.00) | 0.05 |

| Other† | 0.86 (0.59–1.27) | 0.45 | 0.51 (0.37–0.71) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.56–1.27) | 0.42 |

*Withholding or withdrawing treatment.

˚Intensified alleviation of pain and symptoms.

†Includes ‘no answer’.

Compared to physicians that graduated from a Swiss university, those who graduated from abroad reported substantially less often forgoing treatment alone (RRR: 0.30; 95% CI: 0.21–0.41) or combining forgoing treatment with APS (0.44; 0.34–0.55) while for APS alone there was only a marginal effect. Having graduated in 2000 or later had only an effect for the combination of forgoing and APS (1.60; 1.17–2.19), but not for the two "alone" categories. Forgoing life-prolonging treatment alone or combined with APS was less prevalent when physicians reported Catholic as their religious affiliation (0.71 / 0.72; 0.52–0.98 / 0.56–0.92), whereas among Protestant physicians the lower prevalence was predominantly driven by APS. The lowest prevalence however was found for the combination of forgoing and APS among physicians reporting another religious affiliation or philosophy of life (0.51; 0.37–0.71). Male physicians tended to report MELDs less frequently than their female colleagues. In all MELD categories, divorced patients substantially less often experienced an MELD (RRRs between 0.56 and 0.65).

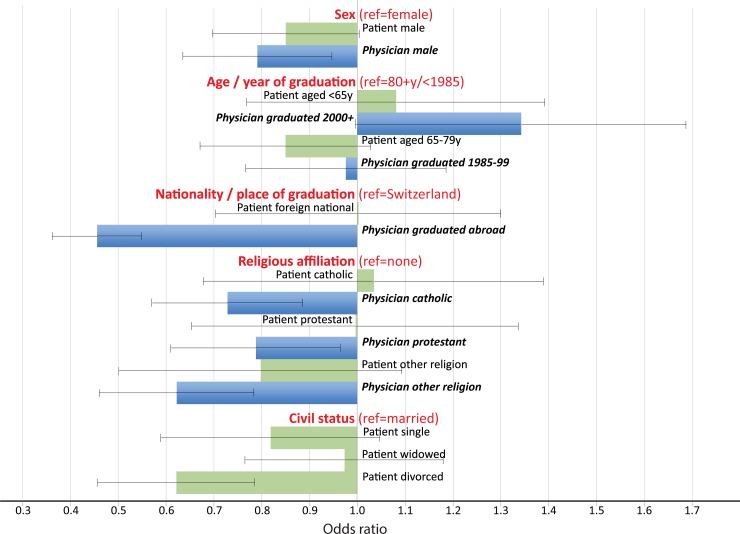

It is tempting to line-up the impact of corresponding physician and patient determinants like sex, age, religious affiliation and foreign origin. The results of a multiple binary logistic regression model (adjusted additionally for the cause of death, place of death and language region) show that physician-related determinants had generally a larger effect size than patient-related ones (Fig 1). Compared to physicians that graduated from a Swiss university, those who graduated abroad reported significantly less often forgoing treatment or APS, whereas nationality of the patient was irrelevant. This contrast between a substantial effect among physicians but only minor effects among decedents also applied to religious affiliation. Only sex showed some similarity: Male patients and even more so patients cared for by a male physician were less likely to die following forgoing treatment or APS.

Fig 1. Patient- vs. physician-related determinants for medical end-of-life decisions (forgoing treatment(s) and/or intensified alleviation of pain): Multiple logistic regression (N = 3,391).

Additionally adjusted for cause of death category, place of death and language region. Patient-related variables are mapped in bright green and physician-related variables in dark blue. Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Patient and family involvement in medical end-of-life decisions

Most MELDs (79%) were discussed with the patient directly or with their relatives (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptives of the study population: Discussion of forgoing treatment and/or APS with patient and/or relatives (N = 2,542).

| Discussed with patient | Discussed with relatives, not with patient | Not discussed with patient or relatives | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 916 | 37.3 | 1087 | 41.4 | 539 | 21.2 |

| MELD category | ||||||

| Forgoing* alone | 181 | 37.3 | 213 | 41.2 | 108 | 21.5 |

| Forgoing* and APS˚ combined | 689 | 41.1 | 779 | 43.4 | 269 | 15.5 |

| APS˚ alone | 46 | 14.9 | 95 | 29.7 | 162 | 55.4 |

| Patient’s characteristics | ||||||

| Patient’s sex: Female | 478 | 36.2 | 580 | 40.7 | 310 | 23.2 |

| Male | 438 | 38.8 | 507 | 42.3 | 229 | 18.9 |

| Patient’s age: <65y | 125 | 42.7 | 113 | 35.8 | 68 | 21.5 |

| 65-79y | 266 | 42.5 | 265 | 40.1 | 114 | 17.4 |

| 80y and over | 525 | 34.4 | 709 | 42.9 | 357 | 22.6 |

| Patient's nationality: Swiss | 837 | 37.2 | 989 | 41.1 | 502 | 21.7 |

| Foreign | 79 | 38.6 | 98 | 45.5 | 37 | 15.9 |

| Patient's religion: Non-religious | 61 | 44.9 | 48 | 34.1 | 30 | 21.0 |

| Catholic | 370 | 37.1 | 467 | 43.8 | 197 | 19.1 |

| Protestant | 368 | 37.4 | 398 | 39.9 | 222 | 22.7 |

| Other† | 117 | 34.2 | 174 | 42.7 | 90 | 23.1 |

| Patient's civil status: Married | 418 | 42.3 | 434 | 42.0 | 165 | 15.7 |

| Single | 77 | 30.3 | 90 | 33.7 | 87 | 36.0 |

| Widowed | 344 | 34.7 | 476 | 44.1 | 221 | 21.2 |

| Divorced | 77 | 35.0 | 87 | 35.1 | 66 | 29.9 |

| Cause of death | ||||||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 198 | 34.9 | 257 | 42.0 | 133 | 23.0 |

| Injury/unknown | 16 | 18.3 | 57 | 60.7 | 19 | 21.0 |

| Cancer | 405 | 53.4 | 230 | 26.3 | 169 | 20.3 |

| Other | 297 | 29.1 | 543 | 50.0 | 218 | 20.9 |

| Physician’s characteristics | ||||||

| Physician’s sex: Female | 339 | 39.6 | 367 | 42.0 | 161 | 18.4 |

| Male | 577 | 36.1 | 720 | 41.1 | 378 | 22.8 |

| Year of graduation: <1985 | 239 | 29.6 | 374 | 42.2 | 237 | 28.6 |

| 1985–1999 | 223 | 38.6 | 251 | 40.2 | 125 | 21.2 |

| >2000 | 454 | 42.6 | 462 | 41.5 | 177 | 15.9 |

| Place of graduation: Switzerland | 730 | 36.7 | 897 | 42.5 | 423 | 20.8 |

| Outside Switzerland | 186 | 40.2 | 190 | 36.7 | 116 | 23.1 |

| Physician’s religion: Non-religious | 302 | 38.0 | 351 | 42.9 | 153 | 19.1 |

| Catholic | 253 | 34.4 | 366 | 43.7 | 174 | 21.9 |

| Protestant | 255 | 39.8 | 248 | 37.0 | 149 | 23.1 |

| Other† | 106 | 37.0 | 122 | 42.1 | 63 | 20.9 |

| Place of death | ||||||

| Hospital‡ | 495 | 42.8 | 507 | 41.3 | 194 | 15.9 |

| Long-term care home | 231 | 30.3 | 351 | 43.6 | 201 | 26.1 |

| Home setting/other§ | 190 | 36.2 | 229 | 38.3 | 144 | 25.5 |

Notes

*Withholding or withdrawing treatment.

˚Intensified alleviation of pain and symptoms.

†Includes ‘no answer’.

‡Includes hospital and palliative care unit/hospice.

§Includes home, elderly care residence, and unspecified ‘other’.

Involvement of the patient was more frequent among cancer patients than on average (53% vs. 37%). In multiple binary logistic regression analysis (not differentiating whether an MELD was discussed directly with the patient or only with relatives), however, there was no substantial variation between the broad cause of death groups. Nevertheless, the type of MELD had a large influence: Compared to forgoing a life-prolonging treatment alone, shared decision-making was substantially more frequent for combined forgoing and APS (OR: 1.51; 95% CI: 1.18–1.95) and much less frequent for APS alone (0.21; 0.15–0.29)(Table 4).

Table 4. Involvement of patient and/or relative(s) in medical end-of-life decisions (MELD): Multiple logistic regression (N = 2,542).

| MELD discussed with patient and/or relative(s) | ||

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| MELD category | ||

| Forgoing* alone | Ref | |

| Forgoing* and APS˚ combined | 1.51 (1.18–1.95) | <0.01 |

| APS˚ alone | 0.21 (0.15–0.29) | <0.001 |

| Patient’s characteristics | ||

| Civil status: Married | Ref | |

| Single | 0.32 (0.23–0.45) | <0.001 |

| Widowed | 0.79 (0.62–1.00) | 0.05 |

| Divorced | 0.41 (0.29–0.58) | <0.001 |

| Physician’s characteristics | ||

| Year of graduation: <1985 | Ref | |

| 1985–1999 | 1.34 (1.03–1.75) | 0.03 |

| >2000 | 1.73 (1.27–2.37) | <0.01 |

| Place of graduation: Switzerland | Ref | |

| Outside Switzerland | 0.65 (0.50–0.87) | <0.01 |

| Place of death | ||

| Hospital‡ | Ref | |

| Long-term care home | 0.69 (0.50–0.96) | 0.03 |

| Home setting/other§ | 0.62 (0.46–0.83) | <0.01 |

*Withholding or withdrawing treatment.

˚Intensified alleviation of pain and symptoms.

‡Includes hospital and palliative care unit/hospice.

§Includes home, elderly care residence, and unspecified ‘other’.

Discussing decisions with the patient or relatives was significantly more likely when physicians graduated more recently (in 1985–1999 / in 2000 or later: 1.34; 1.03–1.75 / 1.73; 1.27–2.37). Conversely, shared decision-making was significantly less likely when physicians graduated outside of Switzerland (0.65; 0.50–0.87) or when patients died elsewhere than in a hospital. Physician's sex and religion or philosophy had no influence on the frequency of discussing decisions with the patient or relatives and were dropped in the final model. Compared to married decedents, shared decision-making was less frequent when patients were single (0.32; 0.23–0.45) or divorced (0.41; 0.29–0.58), but not when they were widowed. Patient's sex, age, nationality and religious affiliation were irrelevant and were also dropped in the final model.

The other potential physician determinants (palliative care education, the importance of religion/life stance for making an MELD, number of deceased patients cared for) were tested but did not have a significant impact on either the likelihood of forgoing and/or APS or the involvement of patients and relatives in decision-making.

Discussion

Even when adjusting for patient and setting characteristics, physician's characteristics had a substantial impact on MELD practices and the prevalence of shared decision-making in our study population, suggesting a sizable potential for optimizing end-of-life care.

International medical graduates made substantially fewer MELDs than those who graduated from a Swiss university and when they made an MELD, they less often reported shared decision-making with the patient and/or their relatives. International medical graduates may be less familiar with shared decision-making and patient-centered care [25]. At the time of the survey, 29% of all physicians in Switzerland were international graduates, with almost 60% of them originating from Germany [26, 27]. A study revealed that German physicians chose more life-prolonging interventions than their Swedish peers [28] and a scoping review stated that "German physicians were found to be more likely to exclude patients, patients' families and non-medical staff from the decision-making process" [4]. In another study, it was shown that where physicians were trained had a significant impact on how often they discussed forgoing treatment with patients [19]. These findings support the notion that physicians’ medical education may have a long-lasting impact on their attitudes towards care and decision-making. Physicians who graduated more recently made more MELDs and discussed these more often with patients and relatives than their colleagues who graduated before 1985. Similarly, a Belgian study found in the late 1990s that MELDs were significantly less frequent among patients treated by GPs aged 55 years and older [29]. This may also be due to previously lacking education in ethics: In Switzerland the first compulsory ethics classes started in 1995 only [30]. Ethics education has been described as supporting physicians' confidence regarding procedural end-of-life issues [31] and as being associated with a higher likelihood of applying a written do not resuscitate order [32]. Physicians inclined to apply "full code" had less often read about end-of-life care and had less interest in discussing MELDs than physicians more disposed to withdrawing life-sustaining therapies [32]. However, a 2002 study showed that ethics education was not associated with confidence in decisions to withdraw life support after an intensive care unit rotation and argued instead for experiential, case-based, patient-centred curricula for physicians-in-training [33].

Moreover and independently of age and place of graduation, physicians' religion mattered: physicians with a religious affiliation made fewer MELDs than those without. This is in line with a former study in Switzerland exploring attitudes regarding hypothetical patients and where religious believers tended to disagree more often with end-of-life decisions than other doctors [34]. On an international level, evidence for an impact of religious belief on the general incidence of MELDs is rather weak and controversial [12]. There is more evidence, however, for non-religious physicians being more inclined to make MELDs that may result in the hastening of death [16,29,35,36], and for a larger impact of religion for more drastic life-shortening acts [13]. Of note, the importance attached to religion when making an MELD had no influence on real patterns in our study and did not support the expectations of intrinsic religiosity of physicians playing a major role [12,34]. In contrast to our expectations, physician's sex had an only marginal influence on MELD incidence and no impact at all regarding the prevalence of shared decision-making. Nevertheless, future research should not discount the possibility of an effect of gender.

Except for the cause of death, civil status was the only patient characteristic with an impact on MELD prevalence. Fairly in line with other studies [6], MELDs were significantly less frequent among divorced patients. In Switzerland, this group accumulated more hospital days in their last year of life than other unmarried people, even when adjusting for the burden of disease and other sociodemographics [37], suggesting suboptimal health care provision. Discussion of MELDs was less frequent for divorced patients, too, as well as for single patients, however not for widowed patients. This is remarkable, since there is evidence that, irrespective of civil status, up to 95% of people had someone they would trust to make medical decisions for them [38]. However, strong social support and formal proxy decision-makers may be rarer among single and divorced patients, leading to fewer opportunities for communication with physicians.

Place of death had a substantial impact on patient involvement, with shared-decision making being more frequent in hospitals than in nursing homes or at home. This differs from the findings of an international study [39], which found that discussion with patients in most countries was more frequent at home than in institutions.

Unsurprisingly, MELD category had a substantial impact on the prevalence of shared decision-making, with more than 80% involvement of patient/relatives when forgoing and APS are combined. In contrast, in the majority of cases of APS alone, physicians included neither patient nor relatives in the decision-making process, although they perceived their decision as a potentially life-shortening act.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Most importantly, the observation unit were deaths and not physicians, i.e., several physicians filled in more than one questionnaire. Due to the anonymous nature of the survey, questionnaires stemming from the same physician could not be identified. Results therefore are not necessarily representative of Swiss physicians. Also, we cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias, since the response rate was, while considerable with respect to the setting, far from 100%. Non-response bias in shared decision-making is also an issue, since 243 questionnaires lacked all information regarding discussion as well as other expression of patient's preferences. However, non-response analysis revealed that the physician's characteristics of this group did not substantially differ from the study population, except an even higher proportion of physicians graduated abroad in the non-response group. The optimal phrasing of the questionnaire remains controversial [40]. This includes the way in which continuous deep sedation is queried, separately from actual MELDs and with less supporting information [41]. However, priority was given to maintain comparability with the international EURELD study [5] and the regular surveys in the Netherlands and Belgium. Finally, the questionnaire does not allow to test whether the actual MELD was in agreement to the preferences of patient and relatives.

Conclusions

The generally high prevalence of MELDs and shared decision-making in Switzerland support the notion that important goals like doctors' timely anticipation of end-of-life and departure from paternalistic medicine are largely accomplished. While there were few differences between patient groups in terms of MELDs or shared decision-making, divorced patients may be disadvantaged in the decision-making process and subsequent MELDs. Physicians should be proactive about engaging single and divorced patients in shared decision-making, possibly by identifying a proxy well in advance. The association between several physician's attributes and MELD practice points to the possibility of inequity in care and a substantial potential for improvement. The findings that older physicians and those graduated from abroad did not only make fewer MELDs but also if they made an MELD, they discussed it less often with patients, strongly call for additional efforts in residency training programs and physicians' vocational education in order to improve communication skills [42], preferably tailored to address local needs and context [43]. Communication has been called 'the cornerstone of good end-of-life care' [44]. An emphasis should also be given to strengthening physicians' motivation [16] and increasing awareness among patients and relatives that death is near [45], both being important elements in the process of improving end-of-life care.

Supporting information

(DTA)

(DTA)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Swiss Federal Statistical Office for having sampled deaths for our study and the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences for ensuring anonymity of questionnaires for the identification of certifying physicians. We are indebted to the many physicians who participated in the study and filled in the questionnaires.

The members of the Swiss Medical End-of-Life Decisions Study Group are Milo Alan Puhan (Chairman), Matthias Bopp, Georg Bosshard (all Zürich), Karin Faisst (St. Gallen), Felix Gutzwiller (Zürich), Samia Hurst (Geneva), Christoph Junker (Neuchâtel), Margareta Schmid, Ueli Zellweger and Sarah Ziegler (all Zürich).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 406740-139309, National Research Program 67 "End-of-Life" (http://www.nfp67.ch/SiteCollectionDocuments/nfp67_portraet_lang_e.pdf). YWHP was partly funded by the Palliative Care Research funding program of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences; the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation; and the Stanley Thomas Johnson Foundation (grant PC 03/16). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bosshard G, Zellweger U, Bopp M, Schmid M, Hurst SA, Puhan MA, Faisst K. Medical end-of-life practices in Switzerland: A comparison of 2001 and 2013. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(4):555–556. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambaere K, Vander Stichele R, Mortier F, Cohen J, Deliens L. (Letter to the editor) Recent trends in euthanasia and other end-of-life practices in Belgium. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1179–1180. 10.1056/NEJMc1414527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Heide A, van Delden JJM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. (Letter to the editor) End-of-life decisions in the Netherlands over 25 years. N Engl J Med 2017;377:492–494. 10.1056/NEJMc1705630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gysels M, Evans N, Meñaca A, Erin A, Toscani F, Finetti S, et al. Culture and end of life care: a scoping exercise in seven European countries. PLoS ONE 2012;7(4):e34188 10.1371/journal.pone.0034188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K, Nilstun T, Norup M, Paci E, et al. End-of-life decision-making in six European countries: descriptive study. Lancet 2003;362:345–350. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14019-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deliens L, Mortier F, Bilsen J, Cosyns M, Vander Stichele, Vanoverloop J, Ingels K. End-of-life decisions in medical practice in Flancers, Belgium: a nationwide survey. Lancet 2000;356:1806–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smets T, Rietjens JA, Chambaere K, Coene G, Deschepper R, Pasman HR, Deliens L. Sex based differences in end-of-life decision making in Flanders, Belgium. Med Care 2012;50:815–820. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182551747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambaere K, Rietjens JAC, Smets T, Bilsen J, Deschepper R, Pasman HRW, Deliens L. Age-based disparities in end-of-life decisions in Belgium: a population-based death certificate survey. BMC Public Health 2012;12:447 10.1186/1471-2458-12-447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans N, Pasman HR, Alonso TV, Van den Block L, Miccinesi G, Van Casteren V, et al. End-of-life decisions: a cross-national study of treatment preference discussions and surrogate decision-maker appointments. PLoS ONE 2013;8(3):e57965 10.1371/journal.pone.0057965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martins Pereira S, Pasman HR, van der Heide A, van Delden JJM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Old age and forgoing treatment: a nationwide mortality follow-back study in the Netherlands. J Med Ethics 2015;41:766–770. 10.1136/medethics-2014-102367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frost DW, Cook DJ, Heyland DK, Fowler RA. Patient and healthcare professional factors influencing end-of-life decision-making during critical illness: A systematic review. Crit Care Med 2011;39(5):1174–1189. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820eacf2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curlin FA, Nwodim C, Vance JL, Chin MH, Lantos JD. To die, to sleep: US physicians' religious and other objections to physician-assisted suicide, terminal sedation, and withdrawal of life support. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2008;25:112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J, van Delden J, Mortier F, Löfmark R, Norup M, Cartwright C, et al. Influence of physicians’ life stances on attitudes to end-of-life decisions and actual end-of-life decision-making in six European countries. J Med Ethics 2008;34:247–253. 10.1136/jme.2006.020297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered communication: a critical review of empirical research. Annu Rev Public Health 2004;25:497–519. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for Medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177(2):206–213. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miccinesi G, Fischer S, Paci E, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Cartwright C, van der Heide A, et al. Physicians' attitudes towards end-of-life decisions: a comparison between seven countries. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:1961–1974. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burns LR, Wholey DR. The effects of patient, hospital, and physician characteristics on length of stay and mortality. Medical Care 1991;29:251–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodwin JS, Salameh H, Zhou J, Siddhartha S, Kuo YF, Nattinger AB. Association of hospitalist years of experience with mortality in the hospitalized Medicare population. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(2):196–203. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eidelman LA, Jakobson DJ, Worner TM, Pizov R, Geber D, Sprung CL. End-of-life intensive care unit decisions, communication, and documentation: an evaluation of physician training. J Crit Care 2003;18(1):11–16. 10.1053/jcrc.2003.YJCRC3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73(3):526–535. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurst S, Zellweger U, Bosshard G, Bopp M. Medical end-of-life practices in Swiss cultural regions: a death certificate study. BMC Medicine 2018;16:54 10.1186/s12916-018-1043-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Rurup ML, Buiting HM, van Delden JJM, Hanssen-de Wolf JE, et al. End-of-life practices in the Netherlands under the euthanasia act. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1957–1965. (Questionnaire available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/suppl/10.1056/NEJMsa071143/suppl_file/nejm_van_der_heide_1957sa1.pdf; accessed July 6, 2018) 10.1056/NEJMsa071143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmid M, Zellweger U, Bosshard G, Bopp M. Medical end-of-life decisions in Switzerland 2001 and 2013: Who is involved and how does the decision-making capacity of the patient impact? Swiss Med Wkly 2016;146:w14307 10.4414/smw.2016.14307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression, Second Edition New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michalski K, Farhan N, Motschall E, Vach W, Boeker M. Dealing with foreign cultural paradigms: A systematic review on intercultural challenges of international medical graduates. PLoS ONE 2017;12(7):e0181330 10.1371/journal.pone.0181330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FMH. FMH Ärztestatistik 2013. https://www.fmh.ch/files/pdf18/FMH-rztestatistik_2013_Poster_D.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2017.

- 27.OECD. OECD.Stat [Internet]; Health workforce migration [cited 2018 April 6]. Available from: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=68337#

- 28.Richter J, Eisemann M, Zgonnikova E. Doctors' authoritarianism in end-of-life treatment decisions. A comparison between Russia, Sweden and Germany. J Med Ethics 2001;27:186–191. 10.1136/jme.27.3.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilsen J, Vander Stichele R, Mortier F, Bernheim J, Deliens L. The incidence and characteristics of end-of-life decisions by GPs in Belgium. Family Practice 2004;21:282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mauron A, Hurst S. Enseigner l'éthique biomédicale en faculté de médecine: l'expérience de l'Université de Genève In: Edwige RA, Piévic M: Un état des lieux de la recherche et de l'enseignement en éthique. Paris: L'Harmattan, 2014, pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sulmasy DP, Geller G, Levine DM, Faden RR. A randomized trial of ethics education for medical house officers. J Med Ethics. 1993;19(3):157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forte DN, Vincent JL, Velasco IT, Park M. Association between education in EOL care and variability in EOL practice: a survey of ICU physicians. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(3):404–412. 10.1007/s00134-011-2400-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens L, Cook D, Guyatt G, Griffith L, Walter S, McMullin J. Education, ethics, and end-of-life decisions in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(2):290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer S, Bosshard G, Faisst K, Tschopp A, Fischer J, Bär W. Swiss doctors’s attitudes towards end-of-life decisions and their determinants. Swiss Med Wkly 2006;136;370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sprung CL, Cohen SI, Sjokvist P, Baras M, Bulow HH, Hovilehto S, et al. End-of-life practices in European intensive care units. The Ethicus study. JAMA 2003;290:790–797. 10.1001/jama.290.6.790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vincent JL. Forgoing life support in western European intensive care units: The results of an ethical questionnaire. Crit Care Med 1999;27:1626–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hedinger D, Braun J, Kaplan V, Bopp M. Determinants of aggregate length of hospital stay in the last year of life in Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:463 10.1186/s12913-016-1725-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hopp FP. Preferences for surrogate decision makers, informal communication, and advance directives among community-dwelling elders: Results from a national study. Gerontologist 2000;40(4):449–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen J, Bilsen J, Fischer S, Löfmark R, Norup M, van der Heide A, et al. End-of-life decision-making in Belgium, Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland: does place of death make a difference? J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:1062–1068. 10.1136/jech.2006.056341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Deliens L, van Delden JJM, van der Maas PJ. End-of-life decisions in the United Kingdom. Palliative Med 2009;23:565–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziegler S, Schmid M, Bopp M, Bosshard G, Puhan MA. Continuous deep sedation until death–a Swiss death certificate study. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33(7);1052–1059. 10.1007/s11606-018-4401-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Triscott JAC, Szafran O, Waugh EH, Torti JMI, Barton M. Cultural transition of international medical graduate residents into family practice in Canada. Int J Med Educ 2016;7:132–141. 10.5116/ijme.570d.6f2c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oczkowski SJ, Chung HO, Hanvey L, Mbuagbaw L, You JJ. Communication tools for end-of-life decision-making in ambulatory care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2016;11(4):e0150671 10.1371/journal.pone.0150671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sleeman KE, Collis E. Caring for a dying patient in hospital. BMJ 2013;346:f2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Korte-Verhoef MC, Pasman HRW, Schweitzer BPM, Francke AL, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Deliens L. General practitioners' perspectives on the avoidability of hospitalizations at the end of life: A mixed-method study. Palliat Med 2014;28:949–958. 10.1177/0269216314528742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DTA)

(DTA)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.