Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of a disease-specific cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) protocol on anxiety and depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in adolescents and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Method

A parallel group randomized controlled trial was conducted in 6 centers of (pediatric) gastroenterology. Included were 70 patients and young adults (10–25 years) with IBD and subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms. Patients were randomized into 2 groups, stratified by center: (a) standard medical care (care-as-usual [CAU]) plus disease-specific manualized CBT (Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training for Physical Illness; PASCET-PI), with 10 weekly sessions, 3 parent sessions, and 3 booster sessions (n = 37), or (b) CAU only (n = 33). Primary analysis concerned the reliable change in anxiety and depressive symptoms after 3 months (immediate posttreatment assessment). Exploratory analyses concerned (1) the course of anxiety and depressive symptoms and HRQOL in subgroups based on age, and (2) the influence of age, gender, and disease type on the effect of the PASCET-PI.

Results

Overall, all participants improved significantly in their anxiety and depressive symptoms and HRQOL, regardless of group, age, gender, and disease type. Primary chi-square tests and exploratory linear mixed models showed no difference in outcomes between the PASCET-PI (n = 35) and the CAU group (n = 33).

Conclusions

In youth with IBD and subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms, preliminary results of immediate post-treatment assessment indicated that a disease-specific CBT added to standard medical care did not perform better than standard medical care in improving psychological symptoms or HRQOL. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02265588.

Keywords: adolescents, cognitive behavioral therapy, depression, inflammatory bowel disease, quality of life, young adults, anxiety

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are two types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). IBD is a chronic disease, that is characterized by episodes of exacerbation (with increased clinical symptoms) and clinical remission. Symptoms are abdominal pain, (bloody) diarrhea, fatigue, fever, and weight loss (Griffiths, 2004). In pediatric IBD (especially CD), malnutrition, resulting in delay of growth and puberty, is common (Sauer & Kugathasan, 2009). Adolescents and young adults (also referred to as youth) with IBD have a high risk for anxiety and/or depression (Mackner, Crandall, & Szigethy, 2006), possibly related to the unpredictable disease course and embarrassing symptoms (Greenley et al., 2010). Moreover, the inflammation-depression(-/anxiety) hypothesis is thought to explain the bidirectional association between inflammation in IBD and anxiety and/or depression. This hypothesis states that inflammation increases vulnerability for emotional symptoms and that treating these symptoms can decrease inflammation and thus improve the disease course (Bonaz & Bernstein, 2013).

In general, prevalence studies show elevated levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms in, respectively, 39%–50% (Kilroy, Nolan, & Sarma, 2011; Reigada et al., 2015) and 38%–55% (Clark et al., 2014; Szigethy et al., 2014) of adolescents with IBD. Only, a few studies report lower prevalence rates (Herzog et al. 2013). Furthermore, a meta-analysis showed higher rates of depressive and internalizing disorders in IBD youth, compared with other chronic conditions (Greenley et al., 2010).

At present, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most effective evidence-based psychological treatment for anxiety and depression in youth (Compton et al., 2004). Until now, only a few studies evaluated CBT for youth with IBD. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), Szigethy et al. (2007) found promising results of a disease-specific CBT in reducing depressive symptoms in 41 adolescents with IBD and subclinical depression. Furthermore, in a later study (N = 178), the same disease-specific CBT was effective in reducing depressive symptoms and improving health-related quality of life (HRQOL). However, supportive nondirective therapy had equally favorable outcomes (Szigethy et al., 2014). Reigada et al. (2013) found improvement in anxiety, pain, and disease activity in nine adolescents with anxiety disorders receiving CBT. In addition, a large recent trial in pediatric patients with IBD (N = 185), not selected on the presence of either somatic or psychological symptoms at baseline, examined the effect of a social learning and cognitive behavioral therapy (SLCBT) of only three sessions versus educational support. Although SLCBT outperformed educational support in improving IBD-related quality of life and school attendance, the authors found no difference between the two groups on anxiety and depression. The authors proposed low levels of disease activity and the short duration of the psychological treatment as possible explanations (Levy et al., 2016).

Taken together, CBT for youth with IBD seems beneficial. The mixed findings described earlier may be due to differences in the included patients, as some studies focused on either anxiety or depression separately (Reigada et al., 2013; Szigethy et al., 2014; Szigethy et al., 2007) or included all IBD patients rather than those selected on anxiety or depression (Levy et al., 2016). However, anxiety can precede depression, and anxiety and depression often occur together (Axelson & Birmaher, 2001; Garber & Weersing, 2010), so investigating both is important. Moreover, for CBT to be effective for anxiety/depression, patients have to experience at least elevated levels of anxiety and/or depressive symptoms, so selecting patients at baseline may be necessary (Mikocka-Walus, Andrews, & Bampton, 2016). Therefore, the present multicenter RCT aims to test the effectiveness of a disease-specific CBT on symptoms of both anxiety and depression as well as on HRQOL in adolescents and young adults with IBD (age = 10–25 years). This age range was chosen to cover the clinically relevant phases of adolescence and young adulthood, when IBD is often diagnosed (Sauer & Kugathasan, 2009) and can affect the many psychosocial changes that take place (e.g., becoming independent and identity formation).

The primary research question was as follows: Compared with standard medical care only, what is the effect of a disease-specific CBT added to standard medical care, on the level of anxiety and depressive symptoms, from pre- to post assessment, in adolescents and young adults with IBD aged 10–25 years?

Additional research questions were as follows: (1) What is the course of anxiety and depressive symptoms and HRQOL in subgroups based on age, regarding the effect of CBT? (2) What is the influence of age, gender, and disease type on the course of anxiety and depressive symptoms and HRQOL, regarding the effect of CBT? By these questions, we aim to examine which patients may benefit most from the disease-specific CBT. We hypothesized that patients in the disease-specific CBT group would improve more on anxiety and/or depressive symptoms and HRQOL compared with patients who received only standard medical care. In addition, we expected to find more effect of CBT in young adult patients (as they already face more life challenges, and could benefit more from the CBT skills than children), in women (as they often experience more anxiety and/or depressive symptoms than men), and in patients with CD (as the systemic symptoms in CD increase the burden of disease). We also investigated how patients (and parents) evaluate the disease-specific CBT (i.e., what is the social validity of the disease-specific CBT).

Method

Design and Procedure

This multicenter parallel group RCT was designed according to the CONSORT guidelines for trials of nonpharmacologic treatments (Boutron et al., 2017). The trial had two arms. Patients in the experimental group received a disease-specific CBT protocol (Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training for Physical Illness; PASCET-PI; Szigethy et al., 2007) added to standard medical care. The control group received standard medical care (care-as-usual, CAU) only, as this resembles the current care best. Initially, only patients 10–20 years old were included. A few months after the start of the recruitment, patients of age 21–25 years were also included, to include more patients in young adulthood as well, to cover the transition phase. The research protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus MC and confirmed by the ethical boards of all participating hospitals. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov as study number NCT02265588.

After having provided written informed consent, patients (and parents) completed validated psychological instruments at two points in time (see Outcome Measures). At baseline, patients completed online questionnaires (at home) and a clinical interview (by phone; no longer than 2 weeks before the start of the PASCET-PI). The immediate post(-treatment) assessment was similar to the baseline and was performed approximately 3 months after baseline, no later than 2 weeks after completing the PASCET-PI. Timing and method of assessments were the same in the experimental and control groups.

Recruitment

Step 1: Inclusion Baseline Screening

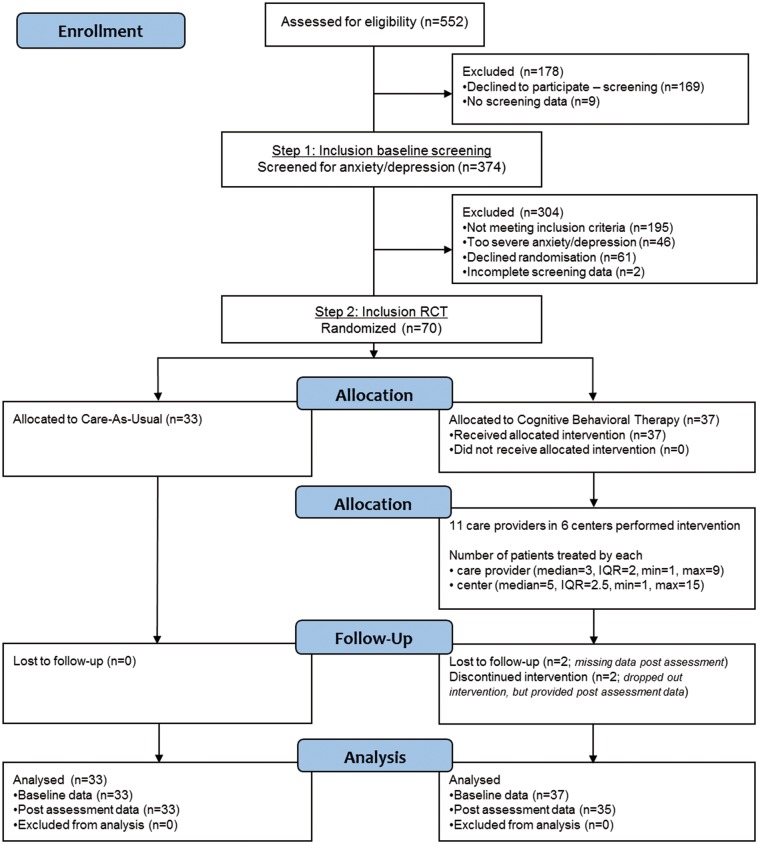

Included for baseline screening for symptoms of anxiety and depression were adolescents and young adults of age 10–25 years with a confirmed diagnosis of IBD (CD, UC, or inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified [IBD-U]; Figure 1). Between October 2014 and October 2016, patients were consecutively recruited from the pediatric or (pediatric) gastroenterology departments of two academic hospitals and four community hospitals. The centers were medium-sized to large hospitals from mixed rural and urban regions. Parents participated for all patients 17 years or younger, whereas parental participation for patients of age 18–20 years was voluntary. Exclusion criteria were (1) intellectual disability; (2) current treatment for mental health problems (pharmacological and/or psychological); (3) insufficient mastery of the Dutch language; (4) a diagnosis of selective mutism, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia/psychotic disorder, autism spectrum disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic or acute stress-disorder, or substance use disorder (parent- or self-reported or from medical file); (5) CBT in the past year (at least eight sessions); and (6) participation in another interventional study, all assessed by the treating physician using medical files (unless otherwise specified).

Figure 1.

CONSORT study flowchart.

Step 2: Inclusion RCT

Only youth with subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms were included in the RCT. Patients with clinical anxiety and/or depression were excluded, as we deemed it unethical to randomize them.

Subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms were defined as a score equal or above the cutoff of age-appropriate questionnaires, but not meeting criteria for clinical anxiety and/or depression (see next paragraph). For anxiety, the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; 10–20 years; cutoff ≥26 for boys and ≥30 for girls; Bodden, Bögels, & Muris, 2009) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—Anxiety Scale (HADS-A; 21–25 years; cutoff ≥8; De Croon, Nieuwenhuijsen, Hugenholtz, & Van Dijk, 2005) were used. For depression, the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; 10–17 years; cutoff ≥13; Timbremont, Braet, & Roelofs, 2008) and the Beck Depression Inventory—second edition (BDI-II; 18–25 years; cutoff ≥14; Van der Does, 2002) were used.

Clinical anxiety and/or depression was defined as follows: for patients who scored on or above the cutoffs for elevated symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, the psychologist-investigator (LS) administered a clinical interview. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (ADIS-C; Siebelink & Treffers, 2001) was delivered by telephone to patients and, if applicable, parents. In the ADIS-C, if a patient meets criteria for a clinical disorder, a clinician’s severity rating (CSR, a 0–8 rating of symptom severity and functional impairment) is assigned by the interviewer. In addition, severity of anxiety and/or depressive symptoms was rated by the interviewer using age-appropriate rating scales. For anxiety, the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS; 10–20 years; cutoff ≥18; Ginsburg, Keeton, Drazdowski, & Riddle, 2011) and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A; 21–25 years; cutoff ≥15; Hamilton, 1959; Matza, Morlock, Sexton, Malley, & Feltner, 2010) were used. For depression, the Child Depression Rating Scale-revised (CDRS-R; 10–12 years; cutoff ≥40; Poznanski et al., 1984), Adolescent Depression Rating Scale (ADRS; 13–20 years; cutoff ≥20; Revah-Levy, Birmaher, Gasquet, & Falissard, 2007), and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D; 21–25 years; cutoff ≥17; Hamilton 1960, Zimmerman, Martinez, Young, Chelminski, & Dalrymple, 2013) were used. If patients met criteria for an anxiety or depressive disorder on the ADIS-C (i.e., a CSR of at least 4) and score equal to or above the clinical cutoff on the rating scale, this indicates a clinical anxiety or depressive disorder. These patients were excluded and received immediate referral to mental health care. Within the group of patients included in the RCT (all with subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms, n = 70), a subdivision was made based on the ADIS-C. If patients had one or more CSRs of at least 4 (but scored below the cutoff on either the CDRS, ADRS, HAM-D, PARS, or HAM-A), they were considered “high” subclinical; if not, they were considered “low” subclinical.

Randomization

Patients with subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms (but not clinical anxiety and/or depression) were randomized to PASCET-PI and CAU versus CAU alone, with a ratio of 1: 1 An independent biostatistician provided a computer-generated blocked randomization list with randomly chosen block sizes (with a maximum of six) and stratification by center using the blockrand package in the R software package, thereby providing numbered envelopes per center. Patients were enrolled by one of the investigators (GB). To prevent drop-out, before randomization, it was thoroughly checked with the patients whether they would be motivated enough to complete the CBT. For example, they were asked about their motivation and concerns regarding traveling and time investment or regarding discussing private information.

Intervention

The PASCET-PI is a disease-specific CBT protocol, developed for adolescents with IBD and depression. Disease-specific components encompass the illness narrative (i.e., perceptions and experience of having IBD), disease-specific psychoeducation, techniques for pain and immune functioning, social skills training, and emphasis on IBD-related cognitions and behavior (Szigethy et al., 2007). Parents receive psychoeducation about coaching their child to cope with IBD.

In the current study, the PASCET-PI contained 10 weekly individual sessions, delivered in 3 months. Conform the protocol, six of these sessions were face-to-face, the remaining four sessions were by phone at a prearranged moment (to advance adherence and lower the treatment burden). In addition, three family sessions (for patients and their parents) were held (only for patients ≤ 20 years), and following the weekly sessions, three monthly individual booster sessions were held by telephone (this was after the immediate post[-treatment] assessment). As the original PASCET-PI was developed for depression, therapists were instructed how to make the exercises more anxiety-tailored, an anxiety hierarchy and step-by-step exercise was added, and an extra anxiety handout was provided to the patients. For patients of age 21–25 years, the practice book was made more age-appropriate. See Van den Brink & Stapersma et al. (2016) or Appendix 1 for a more detailed description of this Dutch modification of the PASCET-PI. The therapy was provided by all licensed (healthcare/CBT) psychologists, who received onsite training from the developer (ES) and performed the therapy in their own hospital or center. To ensure treatment integrity, monthly supervision was provided by EU (clinical psychologist/professor) and audiotaped sessions were rated by EU and five master-level Psychology students. Of all sessions, 30% was rated on adherence by at least one rater, and of that 30%, half was evaluated by at least two raters (i.e. 15% of all sessions). Audiotapes were randomly selected to be rated by two of the raters. However, which pair of two raters rated the sessions varied strongly, so there were too few standardized pairs of raters to use, for example, intraclass correlation. Therefore, interrater agreement was globally calculated using Pearson’s correlation between two data columns with (1) all first ratings and (2) all second ratings for all patients and sessions combined. CAU consisted of regular medical appointments with the (pediatric) gastroenterologist every 3 months, consisting of a 15-min consultation discussing overall well-being, disease activity, results of diagnostics tests, medication use, and future diagnostic/treatment plans.

Outcome Measures (Online Questionnaires)

Demographic data were assessed with a general questionnaire, based on a semi-structured interview (Utens, van Rijen, Erdman, & Verhulst, 2000). Socioeconomic status was based on occupational level from parents or, if they lived on their own, patients themselves. It was divided into low, middle, and high (Statistics Netherlands, 2010). Ethnicity was based on mother’s country of birth or if the mother was born in the Netherlands, the father’s country of birth (Statistics Netherlands, 2000). Disease characteristics were extracted from the medical charts.

Symptoms of anxiety were assessed with the SCARED (for 10–20 years) and the anxiety scale of the HADS (for 21–25 years). Both are self-report questionnaires. The SCARED has 69 items with three response categories (0–2; total score = 0–138). It contains five subscales: General Anxiety Disorder, Separation Anxiety Disorder, Specific Phobia, Panic Disorder, and Social Phobia (Bodden et al., 2009; Muris, Bodden, Hale, Birmaher, & Mayer, 2011). The Anxiety scale of the HADS has seven items with four response categories (0–3; total score = 0–21; De Croon et al., 2005). Internal consistency was .86 and .92 for the SCARED and .54 and .77 for the HADS-A at baseline and follow-up, respectively (Cronbach’s α).

Symptoms of depression were assessed using the CDI (for 10–17 years) and the BDI-II (for 18–25 years) self-report symptom scales. The CDI has 27 items with three response categories (0–2; total score = 0–54; Timbremont et al., 2008). The BDI-II has 21 items with four response categories (0–3; total score = 0–63; Van der Does, 2002). Internal consistency was .70 and .77 for the CDI and .54 and .83 for the BDI-II at baseline and follow-up, respectively.

HRQOL was assessed with the self-reports IMPACT-III (10–20 years) and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ; 21–25 years). The IMPACT-III has 35 items, scored 1–5 (total score = 35–175; Otley et al., 2002). The IBDQ contains 32 items, scored 1–5 (total score = 32–160; De Boer, Wijker, Bartelsman, & de Haes, 1995). A higher score of both instruments indicates better quality of life. Internal consistency was .86 and .89 for the IMPACT-III and .71 and .92 for the IBDQ at baseline and follow-up, respectively.

Clinical disease activity was assessed with four validated clinical disease activity measures. For patients of 10–20 years with CD, the short Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (Kappelman et al., 2011) was used, whereas for patients with UC and IBD-U, the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index was used (Turner et al., 2007). For patients of age 21–25 years with CD, the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (Best, Becktel, Singleton, & Kern, 1976) was used, whereas for patients with UC and IBD-U, the partial Mayo score (Schroeder, Tremaine, & Ilstrup, 1987) was used. All indices were scored by the physician during the medical visit and provide four categories of clinical disease activity: remission, mild, moderate, and severe.

Social validity questions were included in the online questionnaire to gain insight into how the patients in the CBT group (and, if applicable, parents) evaluated the PASCET-PI. For this study, we chose to assess three relevant aspects of social validity: satisfaction, usefulness, and recommendation. Patients and/or parents awarded three items with 0–10 points (0 =“Not at all” to 10 = “Very much”) regarding (1) their satisfaction with the protocol, (2) how useful it was for them, and (3) whether they would recommend it to other patients.

Blinding

The interviewer (LS) and treating physicians were blinded for the result of randomization (they were not informed and had no access to files containing this information). Patients could not be blinded. They were explicitly asked not to discuss the group they were randomized into with their physician.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for demographic and disease characteristics. Independent t-tests and chi-square tests were used to assess differences between these variables in the two groups at baseline. An intention-to-treat principle was applied in the analyses.

For each participant, we calculated a Reliable Change Index (RCI; Jacobson & Truax, 1991) value for anxiety and depression (but not for HRQOL, as no data on test–retest reliability were available for the HRQOL instruments, which are necessary to calculate the RCI). By calculating RCIs, we were able to combine all participants in one analysis. The RCI is calculated using the standard error of measurement of the pretest and the test–retest reliability of the instrument. The RCI can have three possible values: reliably improved, no reliable change, and reliably deteriorated. See Appendix 2 for the details of calculating the RCI variable. A chi-square test was used to compare the RCI values between the two groups, using complete cases (n = 68). For exploratory analyses, we first used six linear mixed models (which take into account missing data) to compare change between the groups from baseline with directly after CBT for anxiety (SCARED or HADS-A), depression (CDI or BDI-II), and HRQOL (IMPACT-III or IBDQ). Time, group (PASCET-PI vs. CAU), and the interaction between time and group were included as fixed factors. We repeated these linear mixed models in subgroups to examine the influence of gender and disease type. The influence of age is incorporated in the first set of linear mixed models, as the questionnaires for the specific age-group were used. Using an identity covariance structure, random intercepts were estimated for each participant. No random slopes could be specified, because we only had two time points. Restricted maximum likelihood was applied as the estimation method. A p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. Reported Cohen’s ds represent the effect size between groups at follow-up. For the SCARED, HADS-A, CDI, and BDI-II, a negative effect size is in favor of CBT; for the IMPACT-III and IBDQ, a positive effect size is in favor of CBT. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.

Sample Size and Power

Considering literature regarding effectiveness of CBT for anxiety and depressive symptoms in youth without a somatic disease, as well as earlier studies of CBT in youth with IBD (Szigethy et al., 2014), we expected medium to large effects on anxiety symptoms (Reynolds, Wilson, Austin, & Hooper, 2012) and medium effects for depressive symptoms (Weisz, McCarty, & Valeri, 2006). This corresponds to ϕ > 0.40 for anxiety symptoms and to ϕ > 0.30 for depressive symptoms. For the chi-square tests for anxiety and depressive symptoms, this means that a total of 70 patients provides us with sufficient power for the anxiety outcomes (>85%) and with medium power for the depression outcomes (>60%).

Results

Demographic, Disease, and Intervention Characteristics

Figure 1 displays the patient flow throughout the study. In total, 70 patients were randomized (10–20 years, n = 50; 21–25 years, n = 20). In Table I, demographic and disease characteristics are displayed for both groups. No significant differences were found between the PASCET-PI group and the CAU group on demographics (e.g., gender and age) and disease characteristics (disease type, activity), nor as to whether patients were included based on anxiety, depression, or both. However, the median disease duration in years was higher in the PASCET-PI group than in the CAU group (2.59 vs. 1.17 years, p = .039).

Table I.

Baseline Demographic and Disease Characteristics

| PASCET-PI group (n = 37) | CAU group (n = 33) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic status | |||

| Male, n (%) | 10 (27.0) | 12 (36.4) | .401a |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 18.62 (4.27) | 17.69 (4.82) | .393b |

| SES, n (%) | |||

| Low | 8 (21.6) | 4 (12.9) | .348a |

| Middle | 15 (40.5) | 10 (32.3) | |

| High | 14 (37.8) | 17 (54.8) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) (n = 64) | |||

| Dutch / Western | 30 (81.1) | 25 (80.6) | .749a |

| Other | 7 (18.9) | 6 (19.4) | |

| Included on, n (%) | |||

| Anxiety | 30 (81.1) | 20 (60.6) | .070a |

| Depression | 0 (0.0) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Both | 7 (18.9) | 10 (30.3) | |

| IBD subtype, n (%) | |||

| Crohn’s disease | 18 (48.6) | 18 (54.5) | .808a |

| Ulcerative colitis | 14 (37.8) | 12 (36.4) | |

| IBD-U | 5 (13.5) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Paris classification at diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| CD: locationf (n = 36) | |||

| L1 | 4 (22.2) | 2 (11.1) | .813a |

| L2 | 4 (22.2) | 4 (22.2) | |

| L3 | 6 (33.3) | 8 (44.4) | |

| + L4a/L4b | 4 (22.2) | 4 (22.2) | |

| CD: behavior (n = 36) | |||

| Nonstricturing, nonpenetrating | 18 (100.0) | 16 (88.9) | .243c |

| Stricturing, penetrating, or both | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.1) | |

| UCe: extentg (n = 34) | |||

| Limited: E1 + E2 | 11 (57.9) | 4 (26.7) | .069a |

| Extensive: E3 + E4 | 8 (42.1) | 11 (73.3) | |

| UCe: severity | |||

| Never severe | 18 (94.7) | 11 (73.3) | .104c |

| Ever severe | 1 (5.3) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Clinical disease activity, n (%) | |||

| Remission | 27 (73.0) | 26 (78.8) | .571a |

| Mild | 10 (27.0) | 7 (21.2) | |

| Disease duration, median, years | 2.59 | 1.17 | .039c |

| IBD medications, n (%) | |||

| Aminosalicylates | 18 (48.6) | 12 (36.4) | .300a |

| Immunomodulators | 16 (43.2) | 16 (48.5) | .660a |

| Biologicals | 8 (21.6) | 12 (36.4) | .173a |

| Corticosteroidsh | 2 (5.4) | 5 (15.2) | .170d |

| Enemas | 3 (8.1) | 1 (3.0) | .352d |

| No medication | 2 (5.4) | 1 (3.0) | .543d |

Note: All demographic and disease characteristics were not significantly different between groups, except for disease duration.

Abbreviations: PASCET-PI = Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training for Physical Illness; CAU = care-as-usual; SD = standard deviation; IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; IBD-U = inflammatory bowel disease unclassified; SES; socioeconomic status.

Chi-square.

ANOVA.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Fisher’s exact test.

UC includes IBD-U patients.

L1: ileocecal, L2: colonic, L3: ileocolonic, L4a: upper gastrointestinal tract proximal, and L4b distal from Treitz ligament.

E1: proctitis, E2: left sided colitis distal of splenic flexure, E3: extensive colitis distal of hepatic flexure, E4: pancolitis.

Prednisone (oral and intravenous) and budesonide (oral).

Regarding treatment integrity, in the PASCET-PI group, 33 (89.2%) patients followed all 10 treatment sessions, one patient (2.7%) followed eight sessions, one patient (2.7%) followed five sessions, one patient (2.7%) followed three sessions, and one patient (2.7%) followed one session. The mean number of treatment sessions followed was 9.38. For the 21 patients whose parents participated as well, 76.2% of the parents followed all three family sessions. The mean number of family sessions was 2.57. In all sessions, at least 75%, and in 75% of the sessions, at least 80% of the required topics were discussed, indicating good adherence to the protocol (i.e., treatment integrity). A global estimation of interrater agreement, over all sessions and patients combined, was calculated. Treatment adherence ratings correlated .41 between the six raters (medium correlation according to Cohen, 1988). No patients in the control group sought mental health care and no study-related adverse events occurred during the trial.

Effect of Disease-Specific CBT on Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety and HRQOL

As some cells in the cross-tabulation were smaller than five, a Fisher’s exact test was performed. In the primary analysis, RCI values did not differ between the two groups for both anxiety (χ2(2) = 1.656, p = .465, ϕ = .159) and depression (χ2(2) = 1.648, p = .523, ϕ = .161; see Table II). Overall, patients in both groups either remained stable or improved in their symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Table II.

Crosstabulation RCI of Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Versus Group

| No reliable change | Reliable increase of score / deterioration | Reliable decrease of score / improvement | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCI categories anxiety (SCARED or HADS-A) | ||||

| CAU | 20 (60.6%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (39.4%) | 33 |

| CBT | 17 (48.6%) | 1 (2.9%) | 17 (48.6%) | 35 |

| Note. Anxiety: χ2 =1.656, df = 2, p = .465, φ = .159 (95%BI 0.00–0.36). Numbers in parentheses indicate row percentages. | ||||

|

RCI categories depression (CDI or BDI-II) |

||||

| CAU | 14 (42.4%) | 1 (3.0%) | 18 (54.5%) | 33 |

| CBT | 14 (40.0%) | 4 (11.4%) | 17 (48.6%) | 35 |

Note. Depression: χ2 =1.648, df = 2, p = .523, φ = .161 (95%BI 0.00–0.37). Numbers in parentheses indicate row percentages.

In the exploratory analyses (see Table III), the same pattern was seen. No significant time–group interaction effect was found for anxiety [SCARED: n = 50, t(47.460) = −0.639, p = .526, d = −0.15; HADS-A: n = 20, t(16.047) = 0.976, p = .343, d = −0.06], depression [CDI: n = 35, t(32.004) = −1.272, p = .212, d = −0.11; BDI-II: n = 35, t(30.739) = −0.363, p = .719, d = −0.47], and HRQOL [IMPACT-III: n = 50, t(45.363) = 1.033, p = .315, d = 0.23; IBDQ: n = 20, t(18.124) = −0.539, p = .597, d = 0.44]. For the SCARED [t(48.059) = −5.709, p < .001], HADS-A [t(16.431) = −4.375, p < .001], BDI-II [t(31.236) = −4.778, p < .001], IMPACT-III [t(45.849) = 4.847, p < .001], and IBDQ [t(18.738) = 2.367, p < .05], the effect of time was significant, whereas for the CDI, this was not the case [t(32.525) = −1.554, p = .130]. These findings show that, after 3 months, all patients improved in their symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as in their HRQOL. Even when these analyses were carried out only in patients who showed relatively “high” subclinical problems (“high” n = 40 vs. “low” n = 30), no group differences were found on the anxiety and depression outcomes (data not shown).

Table III.

Estimated Marginal Means at Baseline and After 3 months for Anxiety, Depression, and Health-Related Quality of Life

| Variable | Baseline | 3 Months | p (time effect) | p (time × group) | Cohen’s d (95%CI) (after 3 months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |||||

| SCARED (0–138) | ||||||

| CBT | 36.2 (2.7) | → | 22.9 (2.6) | <.001 | ||

| CAU | 40.5 (2.8) | → | 25.0 (2.9) | |||

| CBT vs. CAU | .526 | −0.15 (−1.02–0.71) | ||||

| HADS-A (0–14) | ||||||

| CBT | 9.9 (0.7) | → | 7.1 (0.7) | <.001 | ||

| CAU | 9.1 (0.8) | → | 7.3 (0.8) | |||

| CBT vs. CAU | .343 | −0.06 (−1.49–1.37) | ||||

| CDI (0–54) | ||||||

| CBT | 8.5 (1.1) | → | 7.2 (1.1) | .130 | ||

| CAU | 10.8 (1.2) | → | 7.7 (1.2) | |||

| CBT vs. CAU | .212 | −0.11 (−1.11–1.02) | ||||

| BDI-II (0–63) | ||||||

| CBT | 11.3 (1.1) | → | 5.9 (1.1) | <.001 | ||

| CAU | 14.2 (1.2) | → | 8.2 (1.2) | |||

| CBT vs. CAU | .719 | −0.47 (−1.51–0.58) | ||||

| IMPACT-III (35–175) | ||||||

| CBT | 137.1 (2.8) | → | 148.1 (2.8) | <.001 | ||

| CAU | 137.4 (2.9) | → | 144.9 (3.0) | |||

| CBT vs. CAU | .315 | 0.23 (−1.28–0.49) | ||||

| IBDQ (32–224) | ||||||

| CBT | 164.6 (5.8) | → | 179.6 (5.8) | <.001 | ||

| CAU | 161.6 (6.4) | → | 171.2 (6.7) | |||

| CBT vs. CAU | .597 | 0.44 (−2.02–0.77) |

Note. A positive Cohen’s d favors CBT, a negative Cohen’s d favors CAU.

Influence of Age, Gender, and Disease Type on Effect of Disease-Specific CBT on Anxiety and Depression

In exploratory analyses for the four separate age-groups (classified by the four age-attuned questionnaires: SCARED [10–20 years], HADS [21–25 years], CDI [10–17 years], BDI-II [18–25 years]), no differences were found between the groups as to the change in anxiety, depression, or HRQOL. As we did not find group differences in all four age-groups, an age effect seems absent. We explored the possible influence of gender and disease type on the effect of the PASCET-PI by conducting linear mixed model analyses separately in subgroups (male vs. female and CD vs. UC and IBD-U). Overall, none of the subgroup analyses showed a difference between two groups on anxiety, depression, or HRQOL, except for a significant lower score on the BDI-II in the CAU group (n = 6) than in the CBT group (n = 3) for the subgroup analysis in men (data not shown). Therefore, gender and disease type do not seem to influence the effect of CBT.

Social Validity

With respect to satisfaction, patients reported a mean of 7.82 (out of 10), whereas parents reported a mean of 7.50 (out of 10). Mean scores of patients and parents for usefulness were 6.82 and 6.06 (out of 10), respectively. Furthermore, patients reported a mean of 6.96 (out of 10) for recommending it to other patients, and parents reported a mean of 7.25 (out of 10). These results indicate that, in general, patients and their parents evaluated the PASCET-PI positively.

Discussion

The current study, which had very low attrition (< 3%), tested the effect of a disease-specific CBT compared with CAU in reducing subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms and in improving HRQOL, in adolescents and young adults with IBD. At the immediate post(-treatment) assessment, disease-specific CBT added to standard medical care did not perform better than standard medical care. Overall, both the PASCET-PI and CAU group significantly improved over time, on all three outcomes, 3 months after baseline (i.e., at the immediate post[-treatment] assessment). Furthermore, in subgroup analyses, we did not find indications for differences between age-groups, boys versus girls, nor between CD and UC/IBD-U regarding the effect of the PASCET-PI on anxiety, depression, or HRQOL.

Our results are in contrast to results of earlier trials with positive findings of CBT treatment for youth with IBD (Szigethy et al. 2014) but are in accordance with some of the evidence from studies in adults with IBD (McCombie et al. 2013). There are several explanations for our findings.

First, just by participating in the study, patients in the CAU group did not exactly receive standard medical care. They were psychologically assessed at two points in time with questionnaires and interviews. This is not done in routine practice, and therefore, it provided additional exposure to attention from professionals. Usually, only if psychological problems are obvious, the medical team refers patients for mental health care. CAU was chosen as the comparison condition, because it resembles the current care for youth with IBD in our institute best. However, mere participation in the trial may have had a positive effect on all patients due to increased awareness and (unintended) psychoeducation. It has been described before that merely answering questions or participating in a trial can influence behavior or emotions. For example, McCambridge (2015) recently described that the “question-behavior effect” can occur in randomized trials. Moreover, Arrindell (2001) has described the re-test effect: In patients with psychiatric problems, mean scores of psychopathology often decrease at follow-up (without any formal intervention). A first assessment can heighten awareness of anxious or depressive symptoms, which can cause a respondent to try to deal with these symptoms (by talking more about it or try to think different) or lead to more introspection or self-monitoring (Arrindell, 2001). The awareness caused by receiving information about the study and receiving the psychological assessment may have contributed to the fact that all patients improved. It can be perceived as some form of support, like in the control conditions of earlier trials in youth with IBD (Levy et al., 2016; Szigethy et al., 2014).

Second, the overall patient group had a low disease burden, both psychologically as well as somatically. Included patients experienced only subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms, as randomization was not ethical for patients with clinical mental health disorders. We mainly included patients in clinical remission, because for patients with severe disease activity, adherence to the CBT protocol might have been complex. For the subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms, mere participation may have been enough to improve. This raises the question: Which IBD patients should receive psychological treatment? When we analyzed those patients with the highest levels of subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms, still no differences between CBT and CAU were observed. However, a recent trial showed a significant effect of CBT compared with a waiting list on QOL, anxiety, and depression in adult IBD patients, of whom 70% met criteria for a psychiatric disorder (Bennebroek Evertsz’ et al., 2017). This implies that IBD patients with severe psychological problems can actually benefit from CBT. Furthermore, for adolescents with IBD, when compared with supportive therapy, CBT has been shown to improve somatic depressive symptoms as well as clinical disease activity and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, but only in patients with CD and moderate clinical disease activity (Szigethy et al., 2015). This suggests that patients with active disease can benefit from CBT. For these patients, however, sessions should be delivered with great flexibility, as they may not be able to adhere to weekly “live” sessions.

Third, the PASCET-PI may not be suited enough to improve subclinical anxiety and/or depressive symptoms. However, an earlier study using the original PASCET-PI protocol in a group of patients selected on elevated depression did find an effect on these subclinical depressive symptoms, and also on comorbid anxiety disorders (Szigethy et al., 2007). In our trial, patients experienced more anxiety symptoms than depressive symptoms, which may have influenced the results. Nevertheless, CBT is the most evidence-based psychological therapy for both anxiety and depression (Compton et al., 2004). In general, CBT techniques do have an effect on both anxiety and depressive symptoms, with even higher effect sizes found for anxiety than for depression (Weisz et al., 2017). This implies that PASCET-PI may be effective, as to both anxiety and depressive symptoms. In adults with IBD, mixed results are found with respect to the effectiveness of CBT on psychological as well as somatic symptoms (Gracie et al., 2017; McCombie, Mulder, & Gearry, 2013). Several recommendations are made (McCombie et al., 2013; Mikocka-Walus et al., 2016) to focus on patients with, for example, decreased HRQOL or experiencing psychological problems and to take into account high attrition rates in power and sample size calculations. In our trial, these recommendations were covered by selecting patients on anxiety and/or depression and by having very low attrition. The mixed findings in IBD are consistent with mixed findings on the effect of preventive CBT programs for subclinical anxiety and/or depression in youth (Bennett et al., 2015). As our patients experienced subclinical psychological and somatic symptoms, the treatment can be considered as preventive (for the development of clinical disorders). Further studies are needed to examine this type of preventive effects, especially in patients with IBD, as psychological problems can also affect the disease course (Alexakis, Kumar, Saxena, & Pollok, 2017; Van Tilburg et al., 2017).

Fourth, although a sample size of 70 participants should be large enough for the expected effect sizes for CBT on anxiety and/or depression, perhaps we would have found a significant group difference with a larger sample size. Originally, to take into account possible attrition, we aimed to enroll 100 patients (Van den Brink & Stapersma et al., 2016), which we could not achieve. Revised power calculations still indicated that we had sufficient power to investigate the effect of the PASCET-PI, using n = 70. With this sample size, one would expect to see at least a trend toward a difference between the two groups, but this was not the case. Moreover, compared with earlier trials, a strength of the present study was the very low attrition rate and that almost all (95%) patients completed disease-specific CBT.

Fifth, it may be possible that the effect of the PASCET-PI sustains on the longer-term, whereas the effect of the control group diminishes over time. The course of IBD can be fluctuating, and perhaps the knowledge and skills taught in the PASCET-PI can be more useful when patients suffer from more disease activity or flares during a longer period of follow-up. Patients themselves often expressed that this was a motivation to participate in the therapy (“I have no complaints now, but the CBT skills can be useful in the future, when I have a flare”). Data on longer follow-up assessments will be available for analyses later.

In summary, strengths of the current study are that we included patients with a broad and clinical relevant age, with both anxiety and/or depressive symptoms, and that our study had very low attrition. Moreover, no patients in the control group sought mental health care. Furthermore, as our study sites encompass both rural and urban hospitals, this strengthens the generalizability and external validity of our findings. Although the age-specific instruments were most appropriate for the patients in our study, statistically it was a limitation that using different instruments made it difficult to combine all patients in one analysis and that we could perform the linear mixed models only in subgroups. Originally, the study was sufficiently powered to analyze mean symptom change of anxiety and depression. Due to the fact that finally multiple instruments had to be used to cover the age range, this was not possible. However, a revised power calculation for the chi-square analyses with the reliable change index indicated that we had enough power with the total of 70 patients in the RCT. Another limitation was the relatively small sample size. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution. We recommend screening for anxiety and/or depressive symptoms in youth with IBD, as these symptoms can affect the disease course (Alexakis et al., 2017; Van Tilburg et al., 2017) and HRQOL (Engelmann et al., 2015). Subclinical symptoms may develop into more severe psychological disorders, which even have a greater impact (Beesdo, Knappe, & Pine, 2009; Copeland, Shanahan, Costello, & Angold, 2009). CBT may be more effective in patients with more severe psychological symptoms or more IBD disease activity. This, however, should be examined in studies with a different design (i.e., not with standard medical care as the comparison condition). Based on our clinical experience, we consider PASCET-PI as suited also for patients with more severe IBD symptoms but with great flexibility in delivery (over the phone or in the hospital when patients are hospitalized). Yet, future research is needed to find out how the PASCET-PI or CBT can be best delivered to those patients, which patients with IBD benefit most from psychological treatment, but also how the long-term course of disease activity is associated to the long-term course of anxiety/depression.

In conclusion, in our RCT, all patients improved in their symptoms of anxiety and depression and their HRQOL over time (3 months). At the immediate posttreatment assessment, we found no additional effect for a disease-specific CBT on improving subclinical anxiety and depressive symptoms or HRQOL in adolescents and young adults with IBD, when compared with CAU. We hypothesize that the awareness the study elicited and the possible (unintended educational) support provided may have had a strong positive effect on all patients. CBT could be beneficial for patients with more severe psychological symptoms or IBD patients with clinical disease activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their financial supporters Stichting Crohn en Colitis Ulcerosa Fonds Nederland/Maag Lever Darm Stichting, Fonds NutsOhra, Stichting Theia, and Stichting Vrienden van het Sophia. Furthermore, they are very grateful to the patients and their parents who consented, and to the participating hospitals and their professionals who included patients: Erasmus Medical Center (coordinating center), Albert Schweitzer Hospital, Maasstad Hospital, Haga Hospital, Amphia Hospital, and Leiden University Medical Center.

Appendix 1.

Outline of the PASCET-PI (Szigethy et al., 2007; Van den Brink & Stapersma et al., 2016)

| Session number | Content of session |

|---|---|

| Session 1 Live (60 min) | Introduction of ACT & THINK model and PASCET-PI, building work alliance, psycho-education about IBD and depression or anxiety, illness narrative |

| Session 2 Live (60 min) | Mood monitoring, explaining link between feelings, thoughts and behaviors, discussing feeling good and feeling bad, problem-solving |

| Session 3 By telephone (30 min) | Link between behavior and feelings: Activities to feel better |

| Session 4 Live (60 min) | Be Calm and Confident: relaxation exercises |

| Session 5 Live (60 min) | Be Calm and Confident: positive self versus negative self, training social skills |

| Session 6 By telephone (30 min) | Talents: developing talents and skills makes you feel better |

| Session 7 Live (60 min) | Social problem solving, discussing the ACT skills and introduction of the THINK skills with discussing negative thoughts (Think positive) |

| Session 8 By telephone (30 min) | Help from a friend, Identify the ‘Silver Lining’, and No replaying bad thoughts |

| Session 9 By telephone (30 min) | Keep trying – Don’t give up, making several plans to use the ACT & THINK skills |

| Session 10 Live (60 min) | Quiz on ACT & THINK model, discussing use of ACT & THINK skills in the future, updating illness narrative |

| Booster 1 By telephone (30 min) | Several plans to use the ACT & THINK skills, updating illness narrative, personalizing ACT & THINK skills |

| Booster 2 By telephone (30 min) | Several plans to use the ACT & THINK skills, updating illness narrative, personalizing ACT & THINK skills |

| Booster 3 By telephone (30 min) | Several plans to use the ACT & THINK skills, updating illness narrative, personalizing ACT & THINK skills |

| Family 1 Live (60 min) | Parental view on IBD, family situation, psycho-education about IBD and depression or anxiety, introduction of ACT & THINK model and PASCET-PI |

| Family 2 Live (60 min) | Parental view on progress, the ACT & THINK skills that are most effective for the patient, expressing emotions within family, family communication, family stress game |

| Family 3 Live (60 min) | Parental view on progress, family communication, parental depression or anxiety |

Abbreviations: IBD = Inflammatory Bowel Disease; PASCET-PI = Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training for Physical Illness.

Appendix 2. Calculation of Reliable Change Index (RCI) variables

Step 1. Calculating the standard error of difference for each participant, separately for anxiety and depression:

In which x1 and x2 are the individual’s scores on baseline and at follow up, respectively. S1 is the pre-test variance for that instrument. rxx is the test-retest reliability of the instrument as reported in the manual.

SCARED (10-20 years): rxx = .81 (Muris et al., 2011)|S1 = 13.389|Sdiff = 8.253

HADS-A (21-25 years): rxx = .89 (Spinhoven et al., 1997)|S1 = 2.373|Sdiff = 1.113

CDI (10-17 years): rxx = .86 (Timbremont et al., 2008)|S1 = 4.648|Sdiff = 2.459

BDI-II (18-25 years): rxx = .93 (Van der Does, 2002)|S1 = 4.381|Sdiff = 1.639

Step 2. Calculating the difference between the follow up and the baseline for each participant, separately for anxiety and depression.

Step 3. Calculating the RC value for each participant, separately for anxiety and depression.

Step 4. Determining the RCI value for each participant, separately for anxiety and depression. Both for anxiety and depression this leads to a variable with three possible values: no reliable change, reliable deterioration, and reliable improvement. An RC value of between -1.96 and 1.96 indicates no reliable change (p < .05). When RC is higher than 1.96, this indicates a reliable increase in the score (p < .05), i.e. reliable deterioration (as for all the instruments applies that a higher score represents more symptoms). When RC is lower than -1.96, this indicates a reliable decrease in the score (p < .05), i.e. reliable improvement.

Funding

This work was supported by Stichting Vrienden van het Sophia (grant number 985 to J.C.E.), Stichting Crohn en Colitis Ulcerosa Fonds Nederland/Maag Lever Darm Stichting (grant number 14.307.04 to E.M.W.J.U.), Fonds NutsOhra (grant number 1303-012 to E.M.W.J.U.), and Stichting Theia (grant number 2013201 to E.M.W.J.U.).

J.C.E. received financial support from MSD (research support), Janssen (advisory board), and AbbVie (advisory board). E.M.S. received financial support from NIH (grant), Crohn and Colitis Fund America (grant), AbbVie (consultancy), Merck (consultancy), and IHOPE Network (consultancy) and royalties for book editing from APPI. For the remaining authors, none was declared.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Alexakis C., Kumar S., Saxena S., Pollok R. (2017). Systematic review and meta-analysis: The impact of a depressive state on disease course in adult inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 46, 225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrindell W. A. (2001). Changes in waiting-list patients over time: Data on some commonly-used measures. Beware!. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 1227–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D. A., Birmaher B. (2001). Relation between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Depression and Anxiety, 14, 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K., Knappe S., Pine D. S. (2009). Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental Issues and Implications for DSM-V. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 32, 483–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennebroek Evertsz F., Sprangers M. A. G., Sitnikova K., Stokkers P. C. F., Ponsioen C. Y., Bartelsman J. F. W. M., van Bodegraven A. A., Fischer S., Depla A. C. T. M., Mallant R. C., Sanderman R., Burger H., Bockting C. L. H. (2017). Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy on quality of life, anxiety, and depressive symptoms among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85, 918–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett K., Manassis K., Duda S., Bagnell A., Bernstein G. A., Garland E. J., Miller L. D., Newton A., Thabane L., Wilansky P. (2015). Preventing child and adolescent anxiety disorders: Overview of systematic reviews. Depression and Anxiety, 32, 909–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best W. R., Becktel J. M., Singleton J. W., Kern F. Jr. (1976). Development of a Crohn's disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study. Gastroenterology, 70, 439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodden D. H. M., Bögels S. M., Muris P. (2009). The diagnostic utility of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders-71 (SCARED-71). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaz B. L., Bernstein C. N. (2013). Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology, 144, 36–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutron I., Altman D. G., Moher D., Schulz K. F., Ravaud P., Group C. N. (2017). CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: A 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Annals of Internal Medicine, 167, 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. G., Srinath A. I., Youk A. O., Kirshner M. A., McCarthy F. N., Keljo D. J., Szigethy E. M. (2014). Predictors of depression in youth with Crohn disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 585, 569–573. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000000277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Compton S. N., March J. S., Brent D., Albano A. M., Weersing V. R., Curry J. (2004). Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: An evidence-based medicine review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 930–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland W. E., Shanahan L., Costello E., Angold A. (2009). Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 764–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer A. G., Wijker W., Bartelsman J. F., de Haes H. C. (1995). Inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: Cross-cultural adaptation and further validation. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 7, 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Croon E. M., Nieuwenhuijsen K., Hugenholtz N. I. R., Van Dijk F. J. H. (2005). Drie vragenlijsten voor diagnostiek van depressie en angststoornissen. TBV–Tijdschrift voor Bedrijfs-en Verzekeringsgeneeskunde, 13, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann G., Erhard D., Petersen M., Parzer P., Schlarb A. A., Resch F., Brunner R., Hoffmann G. F., Lenhartz H., Richterich A. (2015). Health-related quality of life in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease depends on disease activity and psychiatric comorbidity. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 46, 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J., Weersing V. R. (2010). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in youth: Implications for treatment and prevention. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17, 293–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg G., Keeton C., Drazdowski T., Riddle M. (2011). The utility of clinicians ratings of anxiety using the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS). Child & Youth Care Forum, 40, 93–105. doi: 10.1007/s10566-010-9125-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracie D. J., Irvine A. J., Sood R., Mikocka-Walus A., Hamlin P. J., Ford A. C. (2017). Effect of psychological therapy on disease activity, psychological comorbidity, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2, 189–199. doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(16)30206-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenley R. N., Hommel K. A., Nebel J., Raboin T., Li S. H., Simpson P., Mackner L. (2010). A meta-analytic review of the psychosocial adjustment of youth with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35, 857–869. doi: jsp120 [pii]10.1093/jpepsy/jsp120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A. M. (2004). Specificities of inflammatory bowel disease in childhood. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Gastroenterology, 18, 509–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32, 50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 23, 56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog D., Landolt M. A., Buehr P., Heyland K., Rogler D., Koller R., Rueger V., Pittet V., Nydegger A., Spalinger J., Schäppi M., Schibli S., Braegger C. P.; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. (2013). Low prevalence of behavioural and emotional problems among Swiss paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 98, 16–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N. S., Truax P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 12.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappelman M. D., Crandall W. V., Colletti R. B., Goudie A., Leibowitz I. H., Duffy L., Milov D. E., Kim S. C., Schoen B. T., Patel A. S., Grunow J., Larry E., Fairbrother G., Margolis P. (2011). Short pediatric Crohn's disease activity index for quality improvement and observational research. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 17, 112–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilroy S., Nolan E., Sarma K. M. (2011). Quality of life and level of anxiety in youths with inflammatory bowel disease in Ireland. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 53, 275–279. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318214c13100005176-201109000-00008 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R. L., van Tilburg M. A. L., Langer S. L., Romano J. M., Walker L. S., Mancl L. A., Murphy T. B., Claar R. L., Feld S. I., Christie D. L., Abdullah B., DuPen M. M., Swanson K. S., Baker M. D., Stoner S. A., Whitehead W. E. (2016). Effects of a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention trial to improve disease outcomes in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 22, 2134–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackner L. M., Crandall W. V., Szigethy E. M. (2006). Psychosocial functioning in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 12, 239–244. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000217769.83142.c600054725-200603000-00012 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matza L. S., Morlock R., Sexton C., Malley K., Feltner D. (2010). Identifying HAM-A cutoffs for mild, moderate, and severe generalized anxiety disorder. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 19, 223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J. (2015). From question-behaviour effects in trials to the social psychology of research participation. Psychology and Health, 30, 72–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombie A. M., Mulder R. T., Gearry R. B. (2013). Psychotherapy for inflammatory bowel disease: A review and update. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis, 7, 935–949. doi: S1873-9946(13)00069-X [pii]10.1016/j.crohns.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikocka-Walus A., Andrews J. M., Bampton P. (2016). Cognitive behavioral therapy for IBD. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 22, E5–E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P., Bodden D., Hale W., Birmaher B., Mayer B. (2011). SCARED-NL. Handleiding bij de gereviseerde Nederlandse versie van de Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders. Amsterdam: Boom test uitgevers. [Google Scholar]

- Otley A., Smith C., Nicholas D., Munk M., Avolio J., Sherman P. M., Griffiths A. M. (2002). The IMPACT questionnaire: A valid measure of health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 35, 557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski E. O., Grossman J. A., Buchsbaum Y., Banegas M., Freeman L., Gibbons R. (1984). Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the children's depression rating scale. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 23, 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reigada L. C., Benkov K. J., Bruzzese J.-M., Hoogendoorn C., Szigethy E., Briggie A., Walder D. J., Warner C. M. (2013). Integrating illness concerns into cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and co-occurring anxiety. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursings, 18, 133–143. doi: 10.1111/jspn.12019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reigada L. C., Hoogendoorn C. J., Walsh L. C., Lai J., Szigethy E., Cohen B. H., Bao R., Isola K., Benkov K. J. (2015). Anxiety symptoms and disease severity in children and adolescents with crohn disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 60, 30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revah-Levy A., Birmaher B., Gasquet I., Falissard B. (2007). The Adolescent Depression Rating Scale (ADRS): A validation study. BMC Psychiatry, 7, 2. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-7-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds S., Wilson C., Austin J., Hooper L. (2012). Effects of psychotherapy for anxiety in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 251–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer C. G., Kugathasan S. (2009). Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: Highlighting pediatric differences in IBD. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, 38, 611–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder K. W., Tremaine W. J., Ilstrup D. M. (1987). Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. The. New England Journal of Medicine, 317, 1625–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebelink B. M., Treffers P. D. A. (2001). Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-child version, ADIS-C handleiding. Amsterdam: Harcourt Test Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Netherlands. (2000). Standaarddefinitie allochtonen. The Hague: Statistics Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Netherlands. (2010). Standaard Beroepen Classificatie 2010. The Hague: Statistics Netherlands; Retrieved from https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/onze-diensten/methoden/classificaties/onderwijs-en-beroepen/beroepenclassificatie–isco-en-sbc–/standaard-beroepenclassificatie-2010–sbc-2010–/downloaden-en-installeren-sbc-2010. [Google Scholar]

- Szigethy E., Bujoreanu S. I., Youk A. O., Weisz J., Benhayon D., Fairclough D., Ducharme P., Gonzalez-Heydrich J., Keljo D., Srinath A., Bousvaros A., Kirshner M., Newara M., Kupfer D., DeMaso D. R. (2014). Randomized efficacy trial of two psychotherapies for depression in youth with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 53, 726–735. doi: S0890-8567(14)00297-4 [pii]10.1016/j.jaac.2014.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szigethy E., Kenney E., Carpenter J., Hardy D., Fairclough D., Bousvaros A., Keljo D., Weisz J., Beardslee W. R., Noll R., DeMASO D. R. (2007). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and subsyndromal depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 1290–1298. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180f6341fS0890-8567(09)61847-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szigethy E., Youk A. O., Gonzalez-Heydrich J., Bujoreanu S. I., Weisz J., Fairclough D., Ducharme P., Jones N., Lotrich F., Keljo D., Srinath A., Bousvaros A., Kupfer D., DeMaso D. R. (2015). Effect of 2 psychotherapies on depression and disease activity in pediatric Crohn's disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 21, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timbremont B., Braet C., Roelofs J. (2008). Handleiding Children’s Depression Inventory (herziene versie). Amsterdam: Pearson Assessment and Information B.V. [Google Scholar]

- Turner D., Otley A. R., Mack D., Hyams J., de Bruijne J., Uusoue K., Walters T. D., Zachos M., Mamula P., Beaton D. E., Steinhart A. H., Griffiths A. M. (2007). Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: A prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology, 133, 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utens E. M. W. J., van Rijen E. H. M., Erdman R. A. M., Verhulst F. C. (2000) Rotterdam's Kwaliteit van Leven Interview. Rotterdam: Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology, Erasmus MC; . [Google Scholar]

- Van den Brink G., Stapersma L., El Marroun H., Henrichs J., Szigethy E. M., Utens E. M., Escher J. C. (2016). Effectiveness of disease-specific cognitive-behavioural therapy on depression, anxiety, quality of life and the clinical course of disease in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: Study protocol of a multicentre randomised controlled trial (HAPPY-IBD). BMJ Open Gastroenterology, 3, e000071.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Does A. J. W. (2002). BDI-II-NL Handleiding. De Nederlandse versie van de Beck Depression Inventory (2nd ed.) Lisse: Harcourt Test Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tilburg M. A. L., Claar R. L., Romano J. M., Langer S. L., Drossman D. A., Whitehead W. E., Abdullah B., Levy R. L. (2017). Psychological factors may play an important role in pediatric Crohn's disease symptoms and disability. The Journal of Pediatrics, 184, 94–100.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J. R., Kuppens S., Ng M. Y., Eckshtain D., Ugueto A. M., Vaughn-Coaxum R., Jensen-Doss A., Hawley K. M., Krumholz Marchette L. S., Chu B. C., Weersing V. R., Fordwood S. R. (2017). What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: A multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. American Psychologist, 72, 79–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J. R., McCarty C. A., Valeri S. M. (2006). Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 132–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M., Martinez J. H., Young D., Chelminski I., Dalrymple K. (2013). Severity classification on the Hamilton depression rating scale. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150, 384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]