Hypersplenism is characterized by cytopenia, splenomegaly, increased or normal medullar cellularity, and elevated turnover of the involved cellular line.1–2 The causes of hypersplenism include an increased demand for splenic function, infiltrative diseases of the spleen, and passive splenic congestion due to portal hypertension.3 Hypersplenism resulting from portal hypertension associated with congestive splenomegaly is frequently due to liver cirrhosis.4 No universally accepted therapy has been established for hypersplenism.5 The usual treatment for hypersplenism is splenectomy or splenic embolization.6 However, splenectomy and splenic embolization for hypersplenism may cause a high morbidity and mortality rate.7–10 Although splenic irradiation is a non-invasive and alternative treatment for splenectomy and splenic embolization for patients with hypersplenism due to infiltrative diseases,1 there are few reports on radiotherapy for hypersplenism from congestive splenomegaly. We evaluated the effect of splenic irradiation on the common hematological disorders of hypersplenism (thrombocytopenia, anemia and leucopenia) in patients with hypersplenism from congestive splenomegaly

Patients and Methods

From August 2002 to March 2003, five patients with hypersplenism due to congestive splenomegaly underwent splenic irradiation at the department of radiation oncology, Changhua Christian Hospital, Taiwan. Three were male and two were female. Their ages ranged from 38 to 66 years (median, 46 years). All patients had a history of liver cirrhosis. Three were chronic hepatitis B carriers, and one was a chronic hepatitis C carrier. Two were diagnosed as having hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). One had a drinking history. According to the Child-Pugh classification of liver cirrhosis, three patients were graded as class B, and the other two were class C (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients.

| Patient No. | Sex | Age (years) | Liver cirrhosis | Child-Pugh classification | HBV* carrier | HCV† carrier | HCC‡ | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 54 | + | C | + | − | + | |

| 2 | Male | 66 | + | B | + | − | + | |

| 3 | Female | 46 | + | B | − | − | − | ESRD§ |

| 4 | Male | 42 | + | C | + | − | − | Alcoholism |

| 5 | Female | 38 | + | B | − | + | − | ESRD |

HBV, Hepatitis B virus;

HCV, Hepatitis C virus;

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma;

ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

A Siemens Primus linear accelerator with auto-sequencing multileaf collimator [Siemens Medical Systems, Concord, CA, USA] was used to deliver splenic irradiation. The photon energy was 6 MV. Four patients underwent three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy using an ADAC Pinnacle-3 Treatment Planning System [ADAC Laboratories, Milpitas, CA, USA], and one received conventional radiotherapy with anterior-posterior parallel opposing fields. The total radiation dose was 12 Gγ in 8 fractions, which was delivered with a fraction size of 1.5 Gγ per day, 5 fractions per week. Kidneys were spared in all patients. The follow-up period ranged from 1 to 7 months (mean, 4 months). Physical examination, hematological tests, abdominal sonography and/or abdominal CT scans were performed after radiotherapy to evaluate the response of thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly and splenic pain.

Results

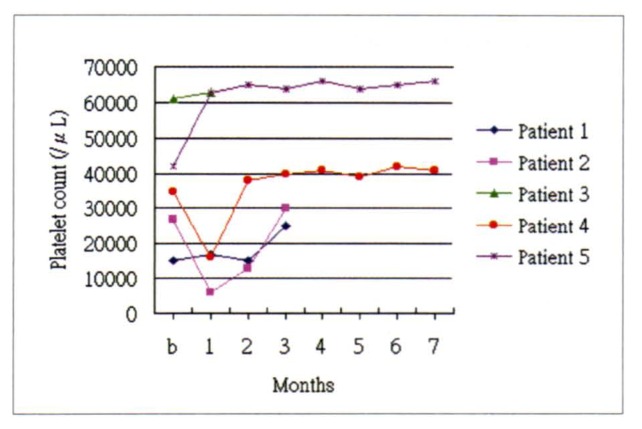

Thrombocytopenia and splenomegaly were found in all five patients by physical examination, hematological tests, abdominal sonography and/or abdominal computed tomography (CT). Two patients had remarkable splenic pain, and four had ascites. Epistaxis, gum bleeding, hemorrhoidal bleeding, and ecchymosis were also noted in four patients. One had impaired renal function, and two were diagnosed as end-stage renal disease (ESRD). All patients presented with depression of more than one cellular element of blood at the initial presentation (Table 2). Platelet count increased in all five patients at the last follow-up visit after radiotherapy, with a mean value of 31% (range 3–66%). Although the platelet counts decreased slightly within one month after radiotherapy, eventually the platelet counts increased (Figure 1). No platelet transfusion was performed within three days of a hematological test. After radiotherapy, thrombocytopenia improved, but leukopenia and anemia did not (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hematological data before and after radiotherapy.

| Patient No. | RBC* | WBC† | Hb‡ | Plts§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (2.85) | (3,200) | (10.5) | (15,000) |

| 1.61 | 6,400 | 6.5 | 25,000 | |

|

| ||||

| 2 | (1.95) | (1,200) | (7.6) | (27,000) |

| 1.62 | 800 | 5.2 | 30,000 | |

|

| ||||

| 3 | (2.49) | (3,600) | (8.1) | (61,000) |

| N/A¶ | N/A | N/A | 63,000 | |

|

| ||||

| 4 | (3.04) | (2,000) | (9.3) | (35,000) |

| 3.39 | 1,800 | 10.5 | 41,000 | |

|

| ||||

| 5 | (2.08) | (2,300) | (7.1) | (42,000) |

| 2.06 | 1,900 | 6.8 | 66,000 | |

|

| ||||

| Mean | (2.48) | (2,460) | (8.5) | (36,000) |

| 2.17 | 2,725 | 7.3 | 45,000 | |

Values in parentheses are the data before radiotherapy, and the timepoint is initial presentation; the data after radiotherapy are the values of the last follow-up;

RBC, red blood cell (106/μL);

WBC, white blood cell (/μL);

Hb, hemoglobin (g/dL);

Plts, platelets (/μL);

N/A, No data available.

Figure 1.

The platelet count before and after radiotherapy. In x-axis, b represents date before radiotherapy; 1–7 represents months after radiotherapy.

The size of spleen was estimated by physical examination, abdominal sonography and/or abdominal CT scan. Splenomegaly improved in two patients after splenic irradiation, with the spleen sizes decreasing by 15% and 70%, respectively. The other three patients had no remarkable response in splenomegaly. By formally assessing pain with a pain scale before and after treatment, splenic pain was relieved completely in 2 of 2 (100%) patients after radiotherapy. Epistaxis, gum bleeding, hemorrhoidal bleeding, and ecchymosis improved in 4 of 4 (100%) patients.

No acute complication due to radiotherapy was found during the follow-up period after splenic irradiation of 12 Gγ in 8 fractions. Two patients died of hepatocellular carcinoma with active bleeding. One patient died of renal failure due to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Discussion

Hypersplenism represents the increased pooling and/or destruction of the corpuscular elements of the blood by the enlarged spleen.11 Liver cirrhosis or portal hypertension is frequently associated with congestive splenomegaly resulting in hypersplenism.4 Our study focused on hypersplenism from congestive splenomegaly due to liver cirrhosis. In Peck-Radosavljevic’s study, thrombocytopenia occurred in 15% to 70% of patients with cirrhosis. Most commonly, thrombocytopenia has been attributed to pooling of platelets in the enlarged spleen induced by portal hypertension.11 Anemia is also a frequently observed manifestation during the clinical course of chronic liver disease.12 In addition, leukopenia is a common clinical sign of hypersplenism.4 Thrombocytopenia, anemia and leukopenia are probably the most common hematological disorders due to hypersplenism from congestive splenomegaly resulting from liver cirrhosis.

Hypersplenism can be treated by splenectomy or partial splenic embolization.6 However, splenectomy in patients with massive splenomegaly and hematological malignancy results in an uncommonly high morbidity and mortality rate because of technical challenges and problems of hemostasis.7–8 In addition, age greater than 50 years and underlying illness are significant factors for morbidity and mortality following splenectomy.13–14 Thrombocytopenia due to hypersplenism has been associated with an increased risk of bleeding when undergoing major surgery.11 Furthermore, splenectomy in patients with hypersplenism can be associated with an increased risk of perioperative complications, overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis (OPSS) and a mortality rate as high as 14%.5,15

Splenic embolization is an alternative treatment for hypersplenism. However, splenic embolization for hypersplenism may cause usual side effects, such as bacterial peritonitis, splenic abscess, and acute or chronic liver failure, especially in patients with noncompensated cirrhosis.16–17 Tarazov reported a high lethality of 18% and a complication rate of 12% after splenic artery embolization for hypersplenism from liver cirrhosis.9 Alwmark’s study revealed an immediate mortality rate of 12%.10

As a non-invasive treatment, splenic irradiation may have a role in managing hypersplenism. In the present study, thrombocytopenia improved in all patients during the follow-up period after radiotherapy. The platelet counts eventually increased by 3% to 66% (mean, 31%). Bleeding and ecchymosis also improved. In contrast, other hematological parameters-hemoglobin, RBC and WBC count-did not return to a normal range. The spleen normally pools about a third of the platelet mass, but in massive splenomegaly the proportion can rise to 90%, resulting in apparent thrombocytopenia.18 However, splenic pooling and sequestration are of minor importance in anemia and leukopenia associated with cirrhosis of liver.11 On the other hand, bleeding, the toxic effects of active ethanol ingestion, and the myelosuppressive activity of hepatitis viruses are factors contributing to the anemia and leukopenia in liver disease.11 These factors may explain why hemoglobin and the RBC and WBC count did not return to a normal range despite improvement of thrombocytopenia and splenomegaly after splenic irradiation. Due to progression of the underlying diseases, two patients died of hepatocellular carcinoma with active bleeding, and one patient died of renal failure due to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). No acute complication associated with irradiation was observed in any patient.

Based on our results, it seems that splenic irradiation might be effective in treating thrombocytopenia and splenomegaly. Splenic irradiation seems to be effective for thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly and splenic pain associated with hypersplenism from congestive splenomegaly. This approach is non-invasive and may be an alternative treatment for splenectomy and splenic embolization for patients with hypersplenism due to congestive splenomegaly. The shortcomings of this study are small sample size, short period of follow-up and lack of randomization. A randomized, controlled trial with more cases and further follow-up of hematological tests and splenic size estimation are warranted to evaluate long-term improvement of congestive splenomegaly with thrombocytopenia after splenic irradiation.

References

- 1.Stolzenbach G, Franke HD, Montz R, Schulze PJ. Spleen irradiation and splenectomy for treatment of hypersplenism in chronic myeloid leukemia and chronic lymphatic leukemia. Strahlentherapie. 1979;155(2):82–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musolino C, Calabro L, Alonci A, Quartarone C, Bellomo G, Neri S. Hypersplenism: current status and perspectives. Recenti Progressi in Medicina. 1999;90(9):488–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry PH, Longo DL. Enlargement of the lymph nodes and spleen. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison’s Principle of Internal Medicine. 15th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 360–365. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pursnani KG, Sillin LF, Kaplan DS. Effect of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt on secondary hypersplenism. Am J Surg. 1997;173(3):169–173. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu-Cheng H, Hwa-Koon W, Albert DY, Tzu-Lung H, Anderson L, Jackson CTL. Evaluation of Partial Splenic Embolization in Patients with Hypersplenism in Cirrhosis. Chin J Radiol. 1999;24(6):233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenawi MM, El-Ghamrawi KA, Mohammad AA, Kenawi A, El-Sadek AZ. Splenic irradiation for the treatment of hypersplenism from congestive splenomegaly. Br J Surg. 1997;84:860–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson EW, Mone MC. Splenectomy in high-risk patients with splenomegaly. Am J Surg. 1999;178(6):581–586. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiatt JR, Gomes AS, Machleder HI. Massive splenomegaly. Superior results with a combined endovascular and operative approach. Arch Surg. 1990;125(10):1363–1367. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410220147021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarazov PG. Follow-up results of splenic artery embolization in liver cirrhosis. Khirurgiia (Mosk) 2000;3:18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alwmark A, Bengmark S, Gullstrand P, Joelsson B, Lunderquist A, Owman T. Evaluation of splenic embolization in patients with portal hypertension and hypertension. Ann Surg. 1982;196(5):518–524. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198211000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peck-Radosavljevic M. Hypersplenism. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:317–323. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bashour FN, Teran JC, Mullen KD. Prevalence of peripheral blood cytopenias (hypersplenism) in patients with nonalcoholic chronic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2936–2939. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Harbi M. Predictors for morbidity and mortality following non-traumatic splenectomy at the University Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Int Surg. 2000;85(4):317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAneny D, LaMorte WW, Scott TE, Weintraub LR, Beazley RM. Is splenectomy more dangerous for massive spleens? Am J Surg. 1998;175(2):102–107. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00264-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sockrider CS, Boykin KN, Green J, Marsala A, Mladenka M, McMillan R, et al. Partial splenic embolization for hypersplenism before and after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2002;16(Suppl 7):59–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.16.s7.9.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakai T, Shiraki K, Inoue H, Sugimoto K, Ohmori S, Murata K, et al. Complications of partial splenic embolization in cirrhotic patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(2):388–391. doi: 10.1023/a:1013786509418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nomiyama K, Akagi K, Watanabe H, Kajiwara E, Sakino I. The effect of partial splenic embolization (PSE) on liver function test in patients with liver cirrhosis. Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi. 1991;82(3):105–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liesner RJ, Machin SJ. Clinical review: ABC of clinical haematology: Platelet disorders. BMJ. 1997;314:809–812. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7083.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]