Abstract

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), via cAMP signaling, inhibits a variety of fibroblast functions relevant to fibrogenesis. Among these are their translation of collagen I protein and their differentiation to myofibroblasts. PKA is central to these actions, with cAMP binding to regulatory (R) subunits leading to the release of catalytic subunits. Here we examined the role of specific PKAR subunit isoforms in these inhibitory actions in transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1)-stimulated human lung fibroblasts (HLFs). HLFs expressed all four R subunit isoforms. siRNA-mediated knockdown of subunits PKARIα and PKARIIα had no effect on PGE2 inhibition of either process. However, knockdown of PKARIβ selectively attenuated PGE2 inhibition of collagen I protein expression, whereas knockdown of PKARIIβ selectively attenuated PGE2 inhibition of expression of the myofibroblast differentiation marker, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). cAMP analogs that selectively activate either PKARIβ or PKARIIβ exclusively inhibited collagen I synthesis or differentiation, respectively. In parallel, the PKARIβ agonist (but not a PKARIIβ agonist) reduced phosphorylation of two proteins involved in protein translation, protein kinase B (AKT) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). By contrast, the PKARIIβ agonist (but not a PKARIβ agonist) reduced levels of the differentiation-associated phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase (p-FAK) as well as the relative mRNA and protein expression of serum response factor (SRF), a transcription factor necessary for myofibroblast differentiation. Our results demonstrate that cAMP inhibition of collagen I translation and myofibroblast differentiation reflects the actions of distinct PKAR subunits.

Keywords: protein kinase A, transforming growth factor β, collagen I, α-smooth muscle actin, PKARIβ, PKARIIβ

substantial morbidity and mortality are associated with fibrotic lung disorders including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Fibroblasts are considered the principal “effector” cells of tissue fibrosis. In fibrosis, these cells exhibit a panoply of dysregulated cellular functions which contribute to their pro-fibrotic phenotype; these include enhanced cell survival, proliferation, deposition of extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen I, and myofibroblast differentiation. TGFβ-1 is a central driver of tissue fibrosis. In fibroblasts, it promotes collagen I mRNA translation (7, 23) and myofibroblast differentiation (25, 29) through distinct pathways. An increase in mRNA translation involves signaling through AKT/mTOR complex (mTORC) 1, with subsequent activation of kinases, translation initiators, and ribosomal proteins (21, 26, 33). Differentiation into myofibroblasts involves activation of FAK/Src kinases and Rho-family GTPases, resulting in the nuclear accumulation of the complex between SRF and myocardin-related transcription factor-A (MRTF-A), which together mediate transcription of contractile genes such as α-SMA (19, 28). As would be expected, inhibition of each of these molecular pathways results in inhibition of the associated phenotypic process (6, 8, 21, 22, 31).

PGE2 is a cyclooxygenase-derived lipid mediator that influences a myriad of biological processes and is the most abundant prostanoid in most tissues. PGE2 exerts anti-fibrotic effects, in part via its ability to inhibit virtually all of the profibrotic processes of activated fibroblasts, including proliferation, apoptosis resistance, myofibroblast differentiation, and collagen I synthesis (9–11, 15, 16, 29). Its importance as an endogenous brake on fibrogenesis is underscored by its deficient generation in the lungs (2) and in lung fibroblasts (35) of patients with IPF. All of these antifibrotic actions are mediated by its ability to increase intracellular cAMP following ligation of the major PGE2 receptor in fibroblasts, termed the E prostanoid 2 receptor (EP2) (9). cAMP is a primordial and ubiquitous second messenger which regulates cell functions through activation of either of two effector molecules, the cAMP-dependent kinase PKA or the guanine nucleotide exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac). We have previously reported that inhibition of specific activation processes in HLFs was differentially mediated by specific cAMP effectors; whereas PGE2/cAMP inhibition of proliferation was mediated by Epac, inhibition of collagen I synthesis and of myofibroblast differentiation was mediated by PKA (10, 22).

PKA is a tetramer composed of two R subunits and two catalytic subunits. The two R subunits, type I and II, each consist of two isoforms, α and β. Binding of cAMP to the R subunit leads to release of the bound catalytic subunits. The freed catalytic subunits mediate biological responses by carrying out phosphorylation on serine/threonine residues of target proteins (30). In view of the multitude of substrate proteins that can be phosphorylated by PKA, how specificity in PKA-mediated responses is accomplished has been a major question in cell biology. Directing PKA to specific substrates requires strict spatial and temporal control and is currently best explained on the basis of differential expression as well as subcellular compartmentalization of particular R subunit isoforms (37). PKARI is preferentially located in the cytosol, whereas PKARII is more likely to be associated with membranes of subcellular structures (27, 36). A means by which specific PKA enzyme pools can be spatially focused to concentrate catalytic activity involves their interactions with A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs), which serve as platforms for signaling complexes (4, 5, 17). Although both types of R subunits can associate with AKAPs, type II subunits are more likely to do so (17, 37). In the present study, we examined the roles of distinct PKAR subunit isoforms in regulating the processes of collagen I translation and myofibroblast differentiation in TGFβ-1-stimulated HLFs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

DMEM, penicillin/streptomycin, and TRIzol were supplied by Life Technologies (Carlsad, CA). TGFβ-1 was supplied by R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was supplied by Hyclone (South Logan, UT). PGE2 was supplied by Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). The primers for qPCR were supplied by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The PKAR subunit siRNA was supplied by Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). PKAR subunit agonists, 2-Cl-8-MA-cAMP (PKARIβ) and Sp-5,6-DCI-cBIMPS (PKARIIβ), were supplied by Biolog (Berlin, Germany). The AKAP/PKARII disruptor, Ht-31, was supplied by Promega (Madison, WI), whereas the AKAP/PKARI disruptor, RIAD, was supplied by Anaspec (Fremont, CA). The phosphatase inhibitor cocktail set II was supplied by Millipore (Billerica, MA).

Antibodies.

The following antibodies for Western blot analysis were supplied by Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA): p-AKT (Tyr308)(D25E6), AKT (C67E7), p-mTOR (Ser2448)(D9C2), and mTOR (7C10). The following antibodies were supplied by BD Transduction Laboratories (San Diego, CA): PKARIIα (clone 40), PKARIIβ (clone 45), and PKARIα (clone 20). The following antibodies were supplied by Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA): PKARIβ (C-19), GAPDH (FL-33), α-SMA (CGA7), and SRF (A-11). The following antibodies were supplied by Thermo Fisher: p-FAK (Tyr397)(PA5-17084) and FAK (MA5-15643). The collagen type 1 (CL50111AP) antibody was supplied by Cedarlane (Burlington, NC). The primary antibody employed for PKARIβ (C-19) immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM) was supplied by Santa Cruz Biotechnology, whereas that for PKARIIβ (clone 45) was supplied by BD Transduction Laboratories. The IgG rabbit (A6154) and mouse (A4416) primary antibodies were supplied by Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Secondary antibodies (mouse and rabbit) for Western blotting and the secondary antibodies Alex Fluor 488 anti-mouse (A11029) (green) and Alex Fluor 568 anti-rabbit (A11036) (red) for IFM were supplied by Life Technologies.

Human lung fibroblast culture.

Normal adult HLFs (CCL210) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin in 75 cm2 flasks. When the fibroblasts reached ~80% confluence in the flasks, they were trypsinized, centrifuged, and resuspended in DMEM + FBS + antibiotics and then plated into Falcon 6-well plates where they were allowed to adhere before the medium was replaced with DMEM + antibiotics.

Experimental treatments.

To stimulate collagen I synthesis or myofibroblast differentiation, cells were treated with TGFβ-1 (2–5 ng/ml) for 24 h after a 30-min pretreatment with or without PGE2 (500 nM), PKAR isoform agonists (500 μM), or AKAP disruptor peptides (RIAD = 50 μM, Ht31 = 100 μM). To stimulate the phosphorylation of translation pathway proteins, cells were treated with TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml) for 20 min (p-AKT) or 4 h (p-mTOR) after a 30-min pretreatment with or without PGE2 (500 nM) or PKAR isoform agonists (500 μM).

Western blot analysis.

After treatment, the cells were lysed with buffer consisting of 1× PBS with 1% NP-40 (vol/vol), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (wt/vol), 0.1% SDS (vol/vol), 1× protease inhibitor, 1:100 dilution of 0.2 M sodium orthovanadate, and 1:100 dilution of phosphatase inhibitor cocktail set II (Millipore). Ten to twenty micrograms of protein for each sample was loaded and run on 4–12% Tris-Glycine gels, transferred onto Whatman Protran BA 83 nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with the primary antibodies indicated. All antibodies were used at titers of 1:500 except for α-SMA and GAPDH, which were used at 1:1,000. Densitometric values for collagen I and α-SMA were normalized to GAPDH from the same membrane. Densitometric values for phosphorylated AKT, mTOR, and FAK were normalized to those for the respective total proteins from the same membrane.

RNA isolation.

RNA was isolated from HLFs in six-well plates by solubilization in 1 ml of TRIzol and transferred to 1.5-ml microfuge tubes. Two-hundred microliters of chloroform was added and the tubes vortexed for 30 s. The tubes were centrifuged in a refrigerated microfuge at 12,000 rpm for 15 min and the upper aqueous phase removed and placed in clean tubes. Five-hundred microliters of propanol was added, the tubes were vortexed and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was decanted from the tubes. One milliliter of 75% ethanol-25% water was added to wash the pellets. The tubes were centrifuged at 7,500 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was carefully decanted from the tubes. The tubes were allowed to air dry for 5 min, and 30 μl of RNase-free water was added. The RNA was quantified in a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

Quantitative PCR.

Relative expression of target RNA was determined on an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus RT-PCR system using the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT). GAPDH was used as a reference gene for SRF. RNA was converted to cDNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit from Applied Biosystems and the cDNA was then amplified using the SYBR Green PCR master mix from Applied Biosystems with the following primers: GAPDH forward 5′-CAGCCTCAAGATCATCAGCA-3′, GAPDH reverse 5′-ACAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGT-3′; SRF forward 5′-CCTACCAGCTTCACCCTCAT-3′, SRF reverse 5′-GTGAGGTCTGTGCTGCTGTC-3′.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

HLFs were plated on four-well chamber slides at 8,000 cells per well in DMEM + 10% FBS + antibiotics and left to adhere for 6 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. After adherence, the medium was replaced with DMEM + antibiotics without FBS and incubated for 24 h. The cells were treated for 30 min with PGE2 followed by a 30-min stimulation with TGFβ-1. The slides were washed twice with cold PBS and the cells fixed by incubating for 15 min with 100% methanol. After fixation, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then blocked in 1.5% BSA, 1.5% goat serum, and 0.5% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature, followed by three, 3-min washes. Primary antibodies against PKARIβ, PKARIIβ, rabbit IgG, and mouse IgG were prepared at a final concentration of 15 µg/ml in 1% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100. After overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4°C, the cells were washed × 3 for 3 min each. The fluorescent secondary antibodies (25 μg/ml) were placed on the cells for 1 h at room temperature in the dark, followed by three, 3-min washes. A DAPI fluorescent stain was placed on the cells for 10 min in the dark, followed by three, 3-min washes. Aqueous mounting medium was added under a coverslip and the cells allowed to sit for 2 h before imaging. The cells were imaged at 40× on a Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope fitted with a Photometrics EZ Cool Snap camera. The images were analyzed with NIS-Elements software (Imager, Dexter, MI). Exposure time was set for each fluorescent dye (DAPI, AlexaFluor 488, and AlexaFluor 568) in the IgG controls, and this exposure time was used across all treatments (control, TGFβ-1, PGE2, and PGE2 + TGFβ-1). Each frame from a given treatment is representative of at least three identical experiments.

RNA silencing.

Five microliters (50 nM) of siRNA targeting each of the four PKAR subunit isoforms as well as a nontargeting control siRNA were suspended in 200 μl of OptiMEM 1 (without antibiotics). The siRNA in OptiMEM was combined with 200 µl of OptiMEM 1 (without antibiotics) containing 5 μl of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX and allowed to incubate for 20 min. CCL210 cells were plated in six-well plates at ~ 200,000 cells per well in DMEM + 10% FBS (without antibiotics), the siRNA-RNAiMAX mixture added to the wells, and the plates allowed to incubate at 37° C in 5% CO2 overnight. The medium was removed and the cells washed with DMEM alone twice. DMEM (with antibiotics) was added to the wells and the cells incubated for 4 days before the addition of experimental agents. Cells from each isoform knockdown condition were treated with TGFβ-1 and/or PGE2 in separate six-well plates, giving each knockdown its own control, TGFβ-1, and PGE2 + TGFβ-1 treatments.

Data analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE of values determined from three or more experiments. SE for controls was obtained by calculating the fold change between the mean control value from replicate experiments and individual control values. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism software using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine significance between the group means. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of PKA regulatory isoform knockdown on PGE2 inhibition of specific fibroblast functions.

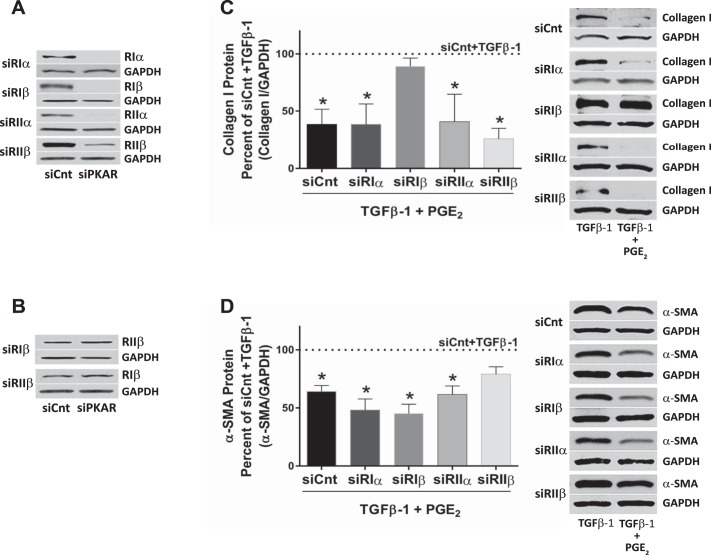

Previous work from our laboratory has shown that translation of the key extracellular matrix protein collagen I and myofibroblast differentiation (as measured by α-SMA) by HLFs can both be inhibited by PGE2 through the EP2/cAMP/PKA pathway (8, 21, 22). Little is known about the expression pattern of PKAR subunit isoforms in HLFs, and our first observation was that these cells indeed express all four R isoforms (Fig. 1A). To investigate the role of specific PKAR subunit isoforms in inhibiting these specific activation processes, we sought to determine the impact of knockdown of each of the four isoforms on the ability of PGE2 (500 nM) to inhibit collagen I and α-SMA protein expression in HLFs treated with the profibrogenic agent TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml); these concentrations of PGE2 and TGFβ-1 were determined to be optimal from our previous studies (9, 13). Cells were transfected with siRNA for each of the four R isoforms in separate six-well plates. When compared with the effects of nontargeting control siRNA, treatment for 4 days with siRNAs targeting the PKAR isoforms markedly (Fig. 1A) and specifically (Fig. 1B) knocked down protein expression of the targeted isoform. When compared with the Lipofectamine controls, 4-day pretreatment with control (nontargeting) siRNA showed no effect on the ability of TGFβ-1 to increase collagen I or α-SMA, or of PGE2 to inhibit these increases in collagen I or α-SMA in response to TGFβ-1. Pretreatment with isoform-specific siRNAs had no effect on the ability of TGFβ-1 to increase collagen I or α-SMA (data not shown). To test the effects of isoform-selective knockdown on PGE2 responses, cells treated for 4 days with siRNAs were pretreated with PGE2 for 30 min before stimulation with TGFβ-1 for 24 h. As expected, the addition of PGE2 significantly reduced levels of collagen I protein in TGFβ-1-stimulated cells that had been transfected with control siRNA. PGE2 also inhibited collagen I protein expression in cells that had been transfected with siRNAs targeting each of the PKAR isoforms except PKARIβ (Fig. 1C). Addition of PGE2 also significantly reduced levels of α-SMA in TGFβ-1-stimulated cells that had been transfected with either control siRNA or with siRNAs targeting each of the PKAR isoforms except PKARIIβ (Fig. 1D). These results demonstrate that although the α-isoforms of R subunits were entirely dispensable for inhibition of both collagen I and differentiation, the two β-subunit isoforms were differentially required for inhibition of these two processes.

Fig. 1.

Knockdown of individual PKAR subunit isoforms specifically prevents the inhibition of collagen I and α-SMA expression by PGE2 in TGFβ-1 stimulated HLFs. A and B: expression and knockdown of PKAR subunit isoform proteins. HLFs were incubated with nontargeting siRNA (siCnt) or siRNA targeting the PKAR subunit isoforms for 4 days in separate 6-well plates, after which cells were harvested for analysis by Western blot of the PKAR isoform and the housekeeping protein GAPDH. C and D: effect of R isoform-specific knockdown on PGE2 inhibition of collagen I protein (C) and α-SMA protein (D). After incubation for 4 days with R isoform-specific siRNA, HLFs were treated for 30 min with or without PGE2 (500 nM) before addition of TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml), and cells were harvested 24 h thereafter for Western blot analysis. Cells from each isoform knockdown condition were treated in separate 6-well plates, giving each knockdown its own control, TGFβ-1, and PGE2 + TGFβ-1 treatments. Blots are from one representative experiment, and graph shows mean and SE values from densitometric analysis of n = 4 independent experiments for collagen I and n = 3 independent experiments for α-SMA. Density of collagen I band and α-SMA band was normalized for GAPDH band in the same sample, and data are expressed as the percent of values from cultures treated with TGFβ-1 only (dotted line). *Significant difference from TGFβ-1 alone, P < 0.05.

Effect of PKA regulatory isoform agonists on specific fibroblast functions.

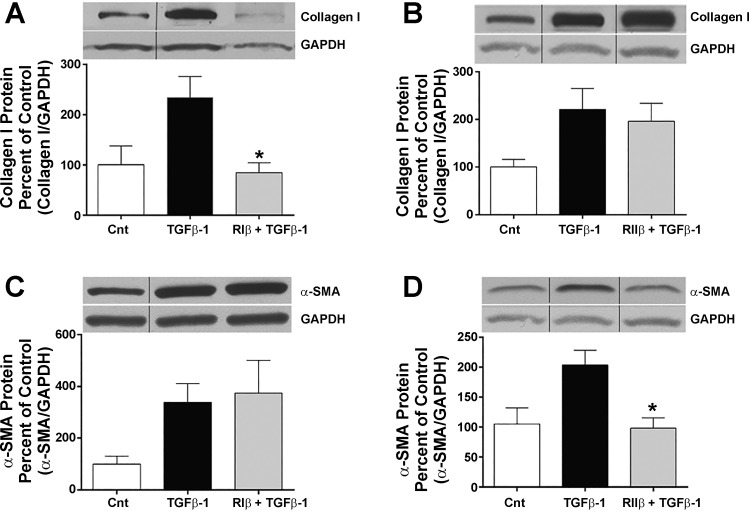

The knockdown studies employed above demonstrated that PKARIβ and PKARIIβ were individually necessary for cAMP-mediated inhibition of collagen I synthesis and myofibroblast differentiation, respectively. To determine if activation of each isoform could selectively inhibit these processes, we employed a pharmacological approach in which HLFs were treated with cAMP analogs that specifically activate holodimers containing either of these isoforms. Cells were pretreated for 30 min with agonists selective for the RIβ isoform (14) and the RIIβ isoform (24) before the addition of TGFβ-1, and cell lysates were harvested 24 h later for analysis. Agonists were used at 500 μM, a concentration typically employed that we have previously used in HLFs (20, 22). Collagen I protein production was significantly reduced by the PKARIβ agonist, but not by the PKARIIβ agonist (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, α-SMA protein production was significantly reduced by the PKARIIβ, but not by the PKARIβ, agonist (Fig. 2, C and D). These results confirm that these two β-isoforms identified from the knockdown experiments as necessary for inhibition of these distinct cell functions are also sufficient to do so.

Fig. 2.

Distinct PKAR subunit agonists inhibit collagen I and α-SMA production in TGFβ-1-stimulated fibroblasts. A and B. inhibition of collagen I protein. C and D. inhibition of α-SMA protein. After 48 h serum starvation, cells were treated with 500 μM of PKARIβ agonist (2-Cl-8-MA-cAMP) (A and C) or PKARIIβ agonist (Sp-5,6-DCI-cBIMPs) (B and D) for 30 min before the addition of TGFβ-1 (2.5 ng/ml), and cells were harvested 24 h thereafter for Western blot analysis. Blots are from one representative experiment, and graph shows mean and SE values from densitometric analysis of n = 5 independent experiments for collagen I and n = 6 independent experiments for α-SMA. Density of collagen I or α-SMA was normalized for GAPDH band in the same sample, and data are expressed as percent of the control value. Lines on blots separate lanes that were from the same blot but were noncontiguous. *Significant difference from TGFβ-1 alone, P < 0.05.

Effect of PKARIβ and PKARIIβ regulatory isoforms on mechanisms controlling specific fibroblast functions.

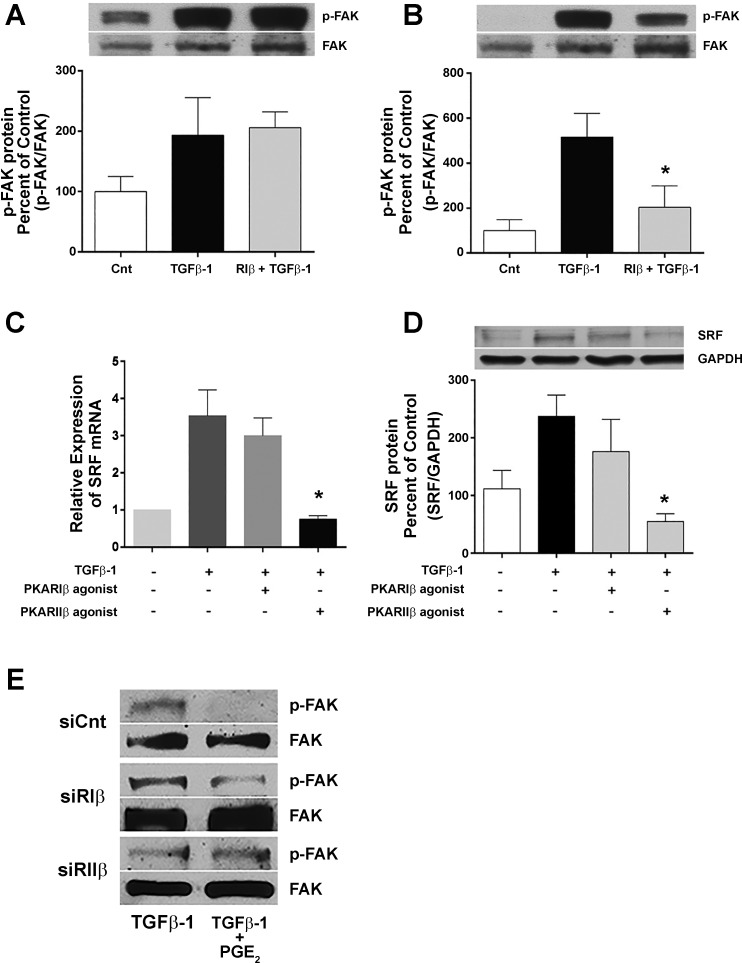

Protein translation typically requires a cascade of phosphorylation events involving intermediate proteins including AKT, mTOR, S6K1, and 4E-BP-1, which ultimately results in the activation of the 40S ribosomal subunit in the translation apparatus. We previously reported that PGE2 inhibition of collagen I protein translation is mediated by inhibition of this cascade in HLFs (21). Given our findings of R subunit isoform specificity in inhibition of collagen I biosynthesis, we next examined the phosphorylation of two of these intermediates in cells treated with isoform-selective cAMP agonists. The cAMP agonists were added for 30 min before the addition of TGFβ-1 and cells harvested for analysis at various time points. As expected, the phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR proteins was increased by TGFβ-1. Moreover, the TGFβ-1-stimulated phosphorylation of these proteins was significantly attenuated by the PKARIβ agonist, but not the PKARIIβ agonist (Fig. 3, A and B). The specific inhibition by PKARIβ of protein translational machinery was corroborated by showing that silencing this isoform also attenuated the inhibitory effect of PGE2 on p-mTOR (Fig. 3C). TGFβ-1 stimulation of myofibroblast differentiation involves signaling through FAK/Src kinases and activation of the MRTF/SRF transcription factor complex (1, 3, 22), and PGE2 has been shown to inhibit these mechanistic events (22). To test whether the inhibition of these events also exhibited PKAR isoform specificity, we added PKARIβ and PKARIIβ agonists to HLF cultures for 30 min before the addition of TGFβ-1 and harvested the cells after 24 h. As expected, TGFβ-1 stimulated the phosphorylation of FAK as well as the induction of SRF mRNA and protein. Both of these events were inhibited by the PKARIIβ agonist, but not by the PKARIβ agonist (Fig. 4). These results were also corroborated by showing that silencing PKARIIβ attenuated the effect of PGE2 on p-FAK (Fig. 4E). Together, these data indicate that the β-isoforms of the type I and type II R subunits selectively inhibit the molecular mechanisms involved in collagen I translation and myofibroblast differentiation, respectively.

Fig. 3.

PKA subunit RIβ agonist inhibits TGFβ-1-stimulated phosphorylation of translational regulatory proteins, and knockdown of PKARIβ protein attenuates PGE2 inhibition of mTOR phosphorylation. Reduced level of phosphorylation of AKT (A) and mTOR (B) in cells treated with PKARIβ agonist (2-Cl-8-MA-cAMP), but not PKARIIβ agonist (Sp-5,6-DCI-cBIMPs). After 24 h of serum starvation, cells were treated with PKAR specific agonists (500 μM) for 30 min before the addition of TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml), and cells were harvested 20 min (A) or 4 h (B) thereafter for Western blot analysis. Blots are from one representative experiment, and graph shows mean and SE values from densitometric analysis of n = 3 independent experiments for each phosphoprotein; density of the phosphoprotein blots was normalized for respective total protein bands in the same sample, and data are expressed as percent of the control value. C: effect of R isoform-specific knockdown on PGE2 inhibition of mTOR protein phosphorylation by TGFβ-1. After incubation for 4 days with R isoform-specific siRNA, HLFs were treated for 30 min with or without PGE2 (500 nM) before addition of TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml), and cells were harvested at 4 h thereafter for Western blot analysis. Blots are from a single experiment. *Significant difference from TGFβ-1 alone, P < 0.05.

Fig. 4.

PKA subunit RIIβ agonist inhibits TGFβ-1-stimulated phosphorylation of FAK and relative expression of SRF. A and B: reduced level of phosphorylation of FAK by PKARIIβ agonist (Sp-5,6-DCI-cBIMPs) (B) but not PKARIβ agonist (2-Cl-8-MA-cAMP) (A). After 24 h of serum starvation, cells were treated with PKAR specific agonists (500 μM) for 30 min before the addition of TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml), and cells were harvested 24 h thereafter for Western blot analysis. Blots are from one representative experiment, and graph shows mean and SE values from densitometric analysis of n = 4 independent experiments for p-FAK. *Significant difference from TGFβ-1 alone, P < 0.001. C and D: inhibition of SRF mRNA (C) and protein (D) expression by PKARIIβ agonist. After 48 h of serum starvation, cells were treated with PKAR specific agonists (500 μM) for 30 min before the addition of TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml), and cells were harvested 24 h thereafter for mRNA analysis by qPCR and protein analysis by Western blot. The graph shows mean and SE values from relative expression of n = 4 independent experiments. Densitometry of SRF protein blots was normalized to GAPDH. Relative expression of SRF was normalized to GAPDH. E: effect of R isoform-specific knockdown on PGE2 inhibition of FAK protein phosphorylation by TGFβ-1 After incubation for 4 days with R isoform-specific siRNA, HLFs were treated for 30 min with or without PGE2 (500 nM) before addition of TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml), and cells were harvested at 4 h thereafter for Western blot analysis. Blots are from a single experiment. *Significant difference from TGFβ-1 alone, P < 0.05.

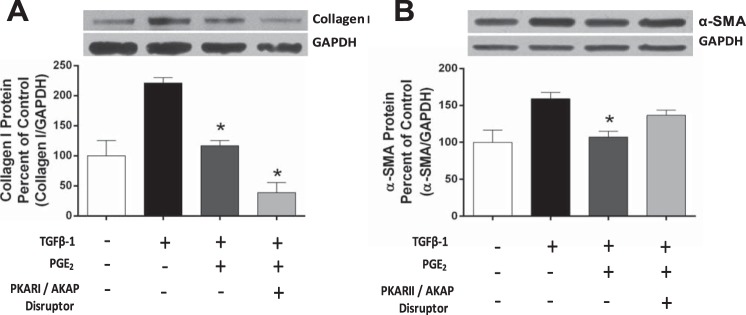

Effect of PKA/AKAP disruptors on PGE2 inhibition of specific fibroblast functions.

AKAPs comprise a large family of proteins that anchor PKAR isoforms to signaling complexes at specific intracellular locales, focusing PKA-mediated actions on substrates within or near those complexes (4, 5). Each R subunit can interact with specific AKAPs (17, 27), and differences in the structure of type I vs. type II R subunits influence both the likelihood (type II > type I) and the nature of their interactions with AKAPs (36). These structural differences have been exploited in the development of cell-permeable peptides that specifically disrupt interactions of type I and type II R subunits with AKAPs (32). We employed such selective AKAP/PKA disruptors both to further validate the isoform specificity involved in regulating specific fibroblast functions and to directly assess the possible role of AKAPs in mediating these regulatory actions of PKA. Peptides were utilized at accepted concentrations as determined previously in HLFs (20). HLFs were pretreated with the AKAP/PKARI disruptor peptide, RIAD (50 μM), for 30 min, followed by addition of PGE2 (500 nM) for 30 min and TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml) for 24 h. Inhibition of collagen I protein expression by PGE2 was unaffected by RIAD (Fig. 5A). In contrast, inhibition of TGFβ-1-induced α-SMA protein expression by PGE2 was overcome by treatment with the AKAP/PKARII disruptor peptide, Ht-31 (100 μM) (Fig. 5B). These data indicate that whereas PKARIβ inhibition of collagen I translation is independent of AKAPs, PKARIIβ inhibition of myofibroblast differentiation depends on its interaction with AKAPs.

Fig. 5.

Differential role of PKAR association with AKAPs for PGE2 inhibition of collagen I and α-SMA expression. A: inhibition of collagen I protein by PGE2 with or without the addition of the PKARI/AKAP disruptor, RIAD. After 24 h of serum starvation, cells were treated with RIAD (50 μM) for 30 min before the addition of PGE2 (500 nM). TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml) was added 30 min later, and cells were harvested 24 h thereafter for Western blot analysis. Blots are from one representative experiment, and graph shows mean and SE values from densitometric analysis of n = 3 independent experiments. B: inhibition of α-SMA protein by PGE2 with or without the addition of the PKARII / AKAP disruptor, Ht31. After 24 h of serum starvation, cells were treated with Ht31 (100 μM) for 30 min before the addition of PGE2 (500 nM). TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml) was added 30 min later, and cells were harvested 24 h thereafter for Western blot analysis. Blots are from one representative experiment, and graph shows mean and SE values from densitometric analysis of n = 4 independent experiments. *Significant difference from TGFβ-1 alone, P < 0.05.

Intracellular localization of PKARIβ and PKARIIβ isoforms.

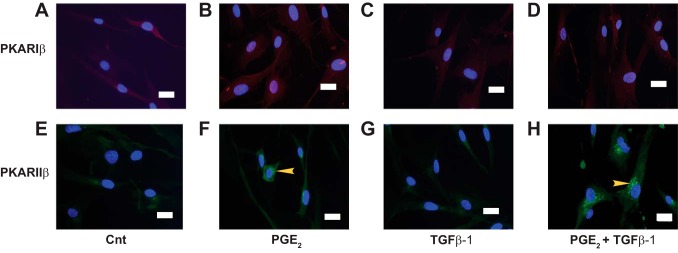

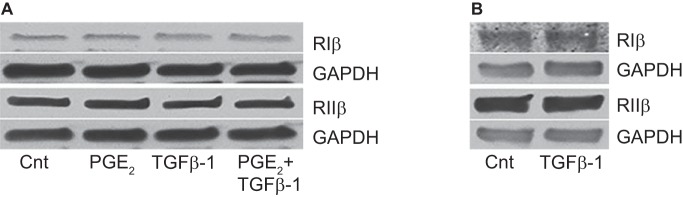

The intracellular distribution of PKAR isoforms was assessed by IFM of HLFs treated for 30 min ± PGE2 followed by a 30 min treatment ± TGFβ-1 (Fig. 6). PKARIβ was found to reside in the cytosol in resting cells (Fig. 6A), and its distribution was unchanged by the addition of either PGE2 (Fig. 6B) or TGFβ-1 (Fig. 6C). PKARIIβ was also localized in the cytosol of resting cells (Fig. 6E); although its distribution was unaffected by the addition of TGFβ-1 (Fig. 6G), it accumulated in the perinuclear region after addition of PGE2 (arrows), either alone (Fig. 6F) or in the presence of TGFβ-1 (Fig. 6H). Treatment with PGE2 and/or TGFβ-1 had no effect on the total cellular level of either isoform protein at either 1 h (Fig. 7A) or 24 h (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 6.

Immunolocalization of PKAR subunit isoform proteins in HLFs. A and E: control. B and F: PGE2 only. C and G: TGFβ-1 only. D and H: PGE2+TGFβ-1. After 24 h serum starvation, cells were treated ± PGE2 (500 nM) for 30 min before the addition of TGFβ-1 (5 ng/ml), and cells were washed and fixed after 30 min. After blocking (1 h), slides were incubated for 24 h with rabbit anti-PKARIβ antibody (A–D) or mouse anti-PKARIIβ antibody (E–H), followed by a 1-h incubation with AlexaFluor 568 (rabbit) or AlexaFluor 488 (mouse) secondary antibodies and a 10-min incubation with DAPI. Micrographs were obtained at 40×. Exposure time was set for each fluorescent dye (DAPI, AlexaFluor 488, and AlexaFluor 568) in the IgG controls (not shown) and used across all treatment conditions. Each image is representative of at least 3 identical experiments. Arrows denote accumulation of PKARIIβ isoform protein in the perinuclear region of the cell. The white scale bar in each image indicates 20 μm.

Fig. 7.

Effect of PGE2 and TGFβ-1 on levels of PKARIβ and PKARIIβ proteins at 1 and 24 h. A: after 24 h serum starvation, cells were treated with PGE2 (500 nM) for 30 min before addition of TGFβ-1 (2.5 ng/ml) and harvested 1 h thereafter for Western blot analysis. Blots are one representative experiment from an n = 2 independent experiments. B: after 24 h serum starvation, cells were treated ± TGFβ-1 (2.5 ng/ml) and harvested 24 h thereafter for Western blot analysis.

DISCUSSION

TGFβ-1 is often considered the master driver of fibrotic tissue remodeling (12, 18). A substantial body of research from our laboratory and others has shown that the lipid mediator PGE2 is capable of opposing many of the fibrogenic actions of TGFβ-1 (13, 15, 16, 22, 29, 34). It can also reverse some of its already established actions, for example, dedifferentiating TGFβ-1-elicited myofibroblasts as evidenced by their loss of phenotype-defining contractile proteins (8). The diverse antifibrotic actions of PGE2 in HLFs all result from ligation of EP2 and signaling via the cAMP pathway (9, 10). However, there is precedent for divergent effectors downstream of cAMP controlling specific fibroblast functions: e.g., inhibition of HLF proliferation being controlled by Epac but inhibition of collagen I synthesis and myofibroblast differentiation being controlled by PKA (10, 22). This underscores the fact that cAMP signaling represents not a single regulatory pathway but rather a collection of individual regulatory pathways. This exquisite degree of specificity makes sense when considering the variety of stimuli that can act via cAMP-coupled receptors (PGE2, prostacyclin, adenosine, β-adrenergic hormones, adrenomedullin) and the myriad of phosphorylation targets for PKA. The fact that the PKA holoenzyme consists of two regulatory subunits (4 isoforms) and two catalytic subunits allows for an additional degree of specificity in the control of different types of cell functions. This rationale motivated our study to examine the specific roles of distinct R subunits in the PKA regulation of collagen I synthesis and myofibroblast differentiation in TGFβ-1-stimulated HLFs.

In some instances, selective actions of specific PKAR isoforms reflect their cell- or tissue-specific expression (4, 27). However, we found that normal HLFs expressed all four of the R isoforms at the protein level, indicating that all of these were potential candidates for mediating inhibition of the cellular functions under investigation. We utilized siRNA-mediated knockdown to explore the relative participation of each isoform in functional inhibition of selected activation events. The two α-isoforms were found to be entirely dispensable for the inhibitory actions of PGE2 on collagen synthesis and myofibroblast differentiation. By contrast, both β-isoforms were necessary for inhibitory actions of PGE2, albeit of distinct cell functions. PGE2 inhibition of collagen I biosynthesis required PKARIβ, whereas its inhibition of differentiation required PKARIIβ (Fig. 1, C and D). These specific actions of each of the β-isoforms were confirmed by addition of cAMP agonists that specifically activate PKARIβ or PKARIIβ, with the former being sufficient to inhibit collagen I production and the latter being sufficient to inhibit α-SMA production (Fig. 2). Further mechanistic analysis using both pharmacological and molecular approaches revealed that PGE2 inhibition of phosphorylation of a cascade of proteins within the translation pathway (21) was mediated by PKARIβ (Fig. 3). At the same time, PGE2 inhibition of FAK phosphorylation and of the expression of SRF mRNA and protein (23)—steps involved in myofibroblast differentiation—was mediated by PKARIIβ (Fig. 4). Since PKA carries out phosphorylation events, our finding that it results in reduced phosphorylation of proteins involved in collagen I translation and myofibroblast differentiation processes implies that these effects must represent indirect downstream events. The substrates whose PKA-catalyzed phosphorylation lie upstream of the dephosphorylation events we have identified remain to be determined, but phosphatases, the mTORC2 assembly protein, rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (RICTOR), or Src kinase represent attractive candidates (1, 31). Further work will be necessary to unravel those steps.

A key question is to understand the mechanisms responsible for the specificity of actions of RIβ in inhibition of collagen I protein translation and of RIIβ in inhibition of the myofibroblast differentiation program. To begin to address this question, we examined the reliance on AKAPs and the spatial distribution of the two isoforms. AKAPs represent one means by which PKAR subunits can be targeted to specific intracellular compartments to focus the enzymatic actions of their associated catalytic subunits. Based on experiments employing cell-permeable peptides which selectively interfere with interactions between AKAPs and either type I or type II subunits, we found that inhibitory effects of RIβ on collagen I synthesis were independent of AKAPs, whereas those of RIIβ on differentiation were AKAP-dependent. This finding is consistent with the observation that type II R subunits are, in general, more likely to interact with AKAPs than are type I subunits. There are >50 specific AKAPs, and the AKAP(s) responsible for anchoring PKARIIβ to carry out inhibition of myofibroblast differentiation remains to be determined.

We also examined the intracellular localization of these isoforms using IFM, and again found differences. Both isoforms were distributed diffusely throughout the cytoplasm of resting cells, and neither their distribution nor total cellular expression changed with addition of TGFβ-1. Addition of PGE2 failed to change the distribution of RIβ. However, its addition resulted in a rapid increase in apparent fluorescence along with a shift in localization of RIIβ, with much of it accumulating in a punctate distribution near the nucleus. Since Western blotting definitively excluded any change in total RIIβ protein in response to PGE2 (Fig. 7A), this perinuclear accumulation is interpreted to reflect a concentration of already existing protein that was previously diffuse in distribution. As AKAP complexes are dynamic entities whose localization can shift with stimulation (36), this relocation of RIIβ may reflect movement of an already AKAP-bound pool or, alternatively, movement of free RIIβ to an AKAP tethered near the nucleus. Differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts is known to involve adhesive signaling (exemplified by activation of FAK) and cytoskeletal rearrangement; these events result in transmission of signals toward the nucleus, where induction of SRF and subsequent induction of a number of contractile proteins including α-SMA occur. We speculate that in response to PGE2 and increases in intracellular cAMP, cAMP-bound RIIβ relocates to a perinuclear site, likely tethered to an AKAP, where it can interfere with cellular machinery involved in myofibroblast differentiation.

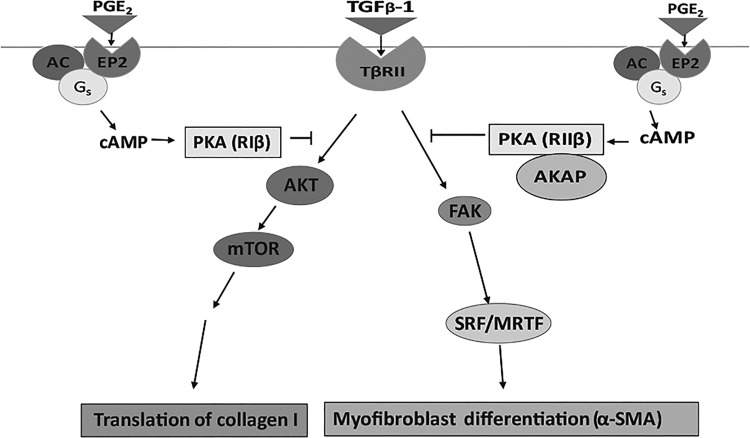

Although all of the antifibrotic actions of PGE2 involve binding to EP2 and generation of the second messenger cAMP, operative pathways diverge downstream of cAMP. We have previously reported that an alternative cAMP effector, Epac, mediates PGE2 inhibition of HLF proliferation (10). Our present studies identify a new level of specificity in PKA control of lung fibroblast processes pertinent to fibrogenesis. In particular, PGE2 inhibition of TGFβ-1- induced collagen I biosynthesis occurs via the actions of unanchored PKARIβ to inhibit activation of a cascade of proteins involved in protein translation machinery. The parallel suppression by PGE2 of myofibroblast differentiation is mediated by AKAP-anchored PKARIIβ inhibition of adhesive signaling and ultimately, of induction of SRF, a master transcription factor controlling expression of contractile genes. A schematic of these distinct pathways is presented in Fig. 8. There is a glaring need for new therapeutic strategies for fibrotic diseases of vital organs, including the lung. Understanding pathways involved in negative regulation of fibroblasts, the key effector cells of fibrotic responses, provides a pivotal framework for possible therapeutic approaches. Our results provide new insights into the negative regulation of HLF functions during exposure to profibrotic stimulation.

Fig. 8.

Schematic summary. TGFβ-1 induces protein translation through the phosphorylation of members of a pathway including AKT and mTOR resulting in the activation of the 40S ribosomal subunit in the translation apparatus. TGFβ-1 induces cell differentiation through phosphorylation of FAK and induction of SRF. The phosphorylation of FAK stimulates the movement of MRTF into the nucleus where it binds to SRF, increasing transcription of α-SMA. PGE2 inhibits these pathways through the EP2 receptor, cAMP, and distinct PKAR subunit isoforms with or without associated AKAPs: RIβ for translation and RIIβ for differentiation.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.H.W. and M.P.-G. conceived and designed research; S.H.W., L.R.P., and K.O. performed experiments; S.H.W. analyzed data; S.H.W. and M.P.-G. interpreted results of experiments; S.H.W. prepared figures; S.H.W. drafted manuscript; S.H.W., L.R.P., K.O., and M.P.-G. approved final version of manuscript; L.R.P., K.O., and M.P.-G. edited and revised manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahamsen H, Vang T, Taskén K. Protein kinase A intersects SRC signaling in membrane microdomains. J Biol Chem : 17170–17177, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211426200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borok Z, Gillissen A, Buhl R, Hoyt RF, Hubbard RC, Ozaki T, Rennard SI, Crystal RG. Augmentation of functional prostaglandin E levels on the respiratory epithelial surface by aerosol administration of prostaglandin E. Am Rev Respir Dis : 1080–1084, 1991. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bromann PA, Korkaya H, Courtneidge SA. The interplay between Src family kinases and receptor tyrosine kinases. Oncogene : 7957–7968, 2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Q, Lin RY, Rubin CS. Organelle-specific targeting of protein kinase AII (PKAII). Molecular and in situ characterization of murine A kinase anchor proteins that recruit regulatory subunits of PKAII to the cytoplasmic surface of mitochondria. J Biol Chem : 15247–15257, 1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dessaur CW. Adenylyl cyclase-A-kinase anchoring protein complexes: The next dimension in cAMP signaling. Mol Pharm : 935–941, 2009. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.059345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hecker L, Jagirdar R, Jin T, Thannickal VJ. Reversible differentiation of myofibroblasts by MyoD. Exp Cell Res : 1914–1921, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fine A, Goldstein RH. Regulation of type I collagen mRNA translation by TGF-beta. Reg Immunol : 218–224, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrison G, Huang SK, Okunishi K, Scott JP, Kumar Penke LR, Scruggs AM, Peters-Golden M. Reversal of myofibroblast differentiation by prostaglandin E(2). Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol : 550–558, 2013. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0262OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang S, Wettlaufer SH, Hogaboam C, Aronoff DM, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E(2) inhibits collagen expression and proliferation in patient-derived normal lung fibroblasts via E prostanoid 2 receptor and cAMP signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol : L405–L413, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00232.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang SK, Wettlaufer SH, Chung J, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits specific lung fibroblast functions via selective actions of PKA and Epac-1. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol : 482–489, 2008. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0080OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang SK, White ES, Wettlaufer SH, Grifka H, Hogaboam CM, Thannickal VJ, Horowitz JC, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E(2) induces fibroblast apoptosis by modulating multiple survival pathways. FASEB J : 4317–4326, 2009. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kajdaniuk D, Marek B, Borgiel-Marek H, Kos-Kudła B. Transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) in physiology and pathology. Endokrynol Pol : 384–396, 2013. doi: 10.5603/EP.2013.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolodsick JE, Peters-Golden M, Larios J, Toews GB, Thannickal VJ, Moore BB. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits fibroblast to myofibroblast transition via E. prostanoid receptor 2 signaling and cyclic adenosine monophosphate elevation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol : 537–544, 2003. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0243OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krakstad C, Christensen AE, Døskeland SO. cAMP protects neutrophils against TNF-α-induced apoptosis by activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, independently of exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac). J Leukoc Biol : 641–647, 2004. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0104005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Ostrom RS, Insel PA. cAMP-elevating agents and adenylyl cyclase overexpression promote an antifibrotic phenotype in pulmonary fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol : C1089–C1099, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00461.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maher TM, Evans IC, Bottoms SE, Mercer PF, Thorley AJ, Nicholson AG, Laurent GJ, Tetley TD, Chambers RC, McAnulty RJ. Diminished prostaglandin E2 contributes to the apoptosis paradox in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med : 73–82, 2010. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0674OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malbon CC, Tao J, Wang HY. AKAPs (A-kinase anchoring proteins) and molecules that compose their G-protein-coupled receptor signalling complexes. Biochem J : 1–9, 2004. doi: 10.1042/bj20031648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng XM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. TGF-β: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol : 325–338, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miralles F, Posern G, Zaromytidou AI, Treisman R. Actin dynamics control SRF activity by regulation of its coactivator MAL. Cell : 329–342, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okunishi K, Sisson TH, Huang SK, Hogaboam CM, Simon RH, Peters-Golden M. Plasmin overcomes resistance to prostaglandin E2 in fibrotic lung fibroblasts by reorganizing protein kinase A signaling. J Biol Chem : 32231–32243, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.235606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okunishi K, DeGraaf AJ, Zasłona Z, Peters-Golden M. Inhibition of protein translation as a novel mechanism for prostaglandin E2 regulation of cell functions. FASEB J : 56–66, 2014. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-231720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Penke LRK, Huang SK, White ES, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits α-smooth muscle actin transcription during myofibroblast differentiation via distinct mechanisms of modulation of serum response factor and myocardin-related transcription factor-A. J Biol Chem : 17151–17162, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.558130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penttinen RP, Kobayashi S, Bornstein P. Transforming growth factor β increases mRNA for matrix proteins both in the presence and in the absence of changes in mRNA stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA : 1105–1108, 1988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poppe H, Rybalkin SD, Rehmann H, Hinds TR, Tang XB, Christensen AE, Schwede F, Genieser HG, Bos JL, Doskeland SO, Beavo JA, Butt E. Cyclic nucleotide analogs as probes of signaling pathways. Nat Methods : 277–278, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0408-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandbo N, Lau A, Kach J, Ngam C, Yau D, Dulin NO. Delayed stress fiber formation mediates pulmonary myofibroblast differentiation in response to TGF-β. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol : L656–L666, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00166.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Showkat M, Beigh MA, Andrabi KI. mTOR signaling in protein translation regulation: Implications in cancer genesis and therapeutic interventions. Mol Biol Int : 686984, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/686984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skalhegg BS, Tasken K. Specificity in the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. Differential expression, regulation, and subcellular localization of subunits of PKA. Front Biosci : D678–D693, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thannickal VJ, Lee DY, White ES, Cui Z, Larios JM, Chacon R, Horowitz JC, Day RM, Thomas PE. Myofibroblast differentiation by transforming growth factor-β1 is dependent on cell adhesion and integrin signaling via focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem : 12384–12389, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas PE, Peters-Golden M, White ES, Thannickal VJ, Moore BB. PGE(2) inhibition of TGF-β1-induced myofibroblast differentiation is Smad-independent but involves cell shape and adhesion-dependent signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol : L417–L428, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00489.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turnham RE, Scott JD. Protein kinase A catalytic subunit isoform PRKACA: history, function and physiology. Gene : 101–108, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker NM, Belloli EA, Stuckey L, Chan KM, Lin J, Lynch W, Chang A, Mazzoni SM, Fingar DC, Lama VN. Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORC2 as key signaling intermediates in mesenchymal cell activation. J Biol Chem : 6262–6271, 2016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.672170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wall EA, Zavzavadjian JR, Chang MS, Randhawa B, Zhu X, Hsueh RC, Liu J, Driver A, Bao XR, Sternweis PC, Simon MI, Fraser ID. Suppression of LPS-induced TNF-alpha production in macrophages by cAMP is mediated by PKA-AKAP95-p105. Sci Signal : ra28, 2009. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Proud CG. The mTOR pathway in the control of protein synthesis. Physiology (Bethesda) : 362–369, 2006. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00024.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White ES, Atrasz RG, Dickie EG, Aronoff DM, Stambolic V, Mak TW, Moore BB, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E(2) inhibits fibroblast migration by E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in PTEN activity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol : 135–141, 2005. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0126OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilborn J, Crofford LJ, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Peters-Golden M. Cultured lung fibroblasts isolated from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have a diminished capacity to synthesize prostaglandin E2 and to express cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest : 1861–1868, 1995. doi: 10.1172/JCI117866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiley JC, Wailes LA, Idzerda RL, McKnight GS. Role of regulatory subunits and protein kinase inhibitor (PKI) in determining nuclear localization and activity of the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A. J Biol Chem : 6381–6387, 1999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong W, Scott JD. AKAP signalling complexes: focal points in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol : 959–970, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nrm1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]