Abstract

We have previously shown that hypoxic proliferation of human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (hPMVECs) depends on epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) activation. To determine downstream signaling leading to proliferation, we tested the hypothesis that hypoxia-induced proliferation in hPMVECs would require EGFR-mediated activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) leading to arginase II induction. To test this hypothesis, hPMVECs were incubated in either normoxia (21% O2, 5% CO2) or hypoxia (1% O2, 5% CO2) and Western blotting was performed for EGFR, arginase II, phosphorylated-ERK (pERK), and total ERK (ERK). Hypoxia led to greater EGFR, pERK, and arginase II protein levels than did normoxia in hPMVECs. To examine the role of EGFR in these hypoxia-induced changes, hPMVECs were transfected with siRNA against EGFR or a scrambled siRNA and placed in hypoxia. Inhibition of EGFR using siRNA attenuated hypoxia-induced pERK and arginase II expression as well as the hypoxia-induced increase in viable cell numbers. hPMVECs were then treated with vehicle, an EGFR inhibitor (AG1478), or an ERK pathway inhibitor (U0126) and placed in hypoxia. Pharmacologic inhibition of EGFR significantly attenuated the hypoxia-induced increase in pERK level. Both AG1478 and U0126 also significantly attenuated the hypoxia-induced increase in viable hPMVECs numbers. hPMVECs were transfected with an adenoviral vector containing arginase II (AdArg2) and overexpression of arginase II rescued the U0126-mediated decrease in viable cell numbers in hypoxic hPMVECs. Our findings suggest that hypoxic activation of EGFR results in phosphorylation of ERK, which is required for hypoxic induction of arginase II and cellular proliferation.

Keywords: hypoxia, pulmonary vascular remodeling, pulmonary hypertension, arginase

pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a disease characterized by vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling of the microvasculature, which leads to decreased luminal diameter (9, 17). The aberrant vascular remodeling, the hallmark of PH, may have some similarities to the abnormal cell proliferation seen in malignancies (5, 7). Currently, there are no therapies to treat the problem of abnormal vascular remodeling that is central to the development of PH (9). The World Health Organization (WHO) has categorized PH into five clinical classifications (groups): 1) pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH); 2) PH due to left heart disease; 3) PH associated with respiratory disease and hypoxemia [including chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD)]; 4) chronic thromboembolic PH; and 5) PH with unclear multifactorial mechanism (23). Despite the heterogeneous nature of the groups in the WHO classification, many forms of PH present with similar pathological changes and vasoconstriction, endothelial dysfunction, and/or cellular proliferation are key components of disease progression in all groups of PH (26). Endothelial cells play a key role in the development of PH (17), although this role may differ in various forms of PH. One way that endothelial cells can contribute to PH is by proliferation and thereby a direct contribution to the decreased luminal diameter seen in PH, and this particular phenomena has been described in PAH (21, 27). Another way that endothelial cells can contribute to PH is by releasing factors that can act on other cells in the vessel wall, particularly smooth muscle cells, to promote proliferation and remodeling contributing to the decreased luminal diameter (8, 17, 28). We have previously utilized hypoxia as a stimulus in cell culture models to examine alterations in proliferation (1, 2, 6, 25). Interestingly, in neonatal/pediatric causes of PH such as that seen with BPD, lack of vasculogenesis is an important underlying cause of the PH and leads to alterations in structure and pulmonary vasomotor tone (12). In the developing lung, unlike in the adult lung, pro-proliferative factors released from the endothelium may be necessary for normal pulmonary vascular development. Thus the role of abnormal endothelial proliferation and/or endothelial release of pro-proliferative factors in the pathogenesis of PH are most directly related to plexiform PH as seen in many adult conditions.

Polyamines and proline are critical for cellular proliferation, and arginase mediates the first step in polyamine and proline synthesis in cells (19). Arginase metabolizes l-arginine to l-ornithine and urea, and l-ornithine can then be metabolized to proline via ornithine amino transferase or to polyamines via ornithine decarboxylase. There are two isoforms of arginase, arginase I and arginase II. Arginase I is highly expressed in the liver and critical in the urea cycle, while arginase II is often referred to as the inducible form and is not expressed in the liver (19). We have previously shown in human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (hPMVECs) that hypoxia-induced proliferation in hPMVECs depends on the receptor tyrosine kinase epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and that activation of EGFR leads to arginase II induction (25). However, the signal transduction pathway leading from EGFR to arginase II induction is unknown. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signal transduction pathway has been shown to be critical for cellular survival and/or proliferation in response to various stressors in a variety of cell types (15, 16). ERK is part of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, which also includes c-JUN NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38. The MAPKs are a family of serine/threonine protein kinases highly conserved in eukaryotic species (16). We hypothesized that in hPMVECs hypoxia-induced EGFR activation leads to phosphorylation of ERK resulting in increased arginase II expression and cellular proliferation. To test our hypothesis, we studied hPMVECs exposed to hypoxia. The levels of EGFR, phosphorylated-ERK (pERK), total ERK, and arginase II were assessed by Western blotting. We also assessed effects on proliferation by assaying viable cell numbers. We utilized EGFR inhibition or ERK inhibition using specific pharmacological inhibitors and/or EGFR small interfering RNA (siRNA). We also used adenoviral mediated overexpression of arginase II to determine the role of arginase II in ERK-mediated proliferation. Finally, to examine the role of endothelial ERK in the release of factors from the endothelium that could promote smooth muscle cell proliferation, we utilized conditioned media from hPMVECs placed on human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs).

METHODS

Human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells.

hPMVECs were purchased from Lonza (catalog no. ml-2527, lot no. 0000366560; Allendale, NJ) and grown in six-well plates according to the manufacturer’s recommendations using endothelial cell basal medium (EBM2; Lonza) supplemented with an EGM-2 bullet kit (Lonza) as described previously (6, 25). On the day of study, the hPMVECs were washed three times with 2 ml of Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS). Fresh medium was placed on the hPMVECs and the cells were returned to the incubator at 37°C in 5% CO2 for either 1 or 24 h. The hPMVECs were washed three times with 4 ml HBSS and treated with lysis buffer for protein extraction. In another set of experiments, hPMVECs were treated with either vehicle or a small molecule inhibitor of either EGFR (AG1478, 1 µM) or the ERK pathway (U0126, 10 µM) and incubated in hypoxia (5% CO2, 1% O2) for 1 h. Cells were treated with lysis buffer for protein extraction.

In siRNA-treated cells, hPMVECs were transfected with siRNA against human EGFR (Silencer Select ID no. s563, catalog no. 4390824, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), or scrambled siRNA as a control, using transfection reagents provided by the manufacturer as previously described (15, 25). Cells were allowed to recover in the incubator at 37°C (5% CO2, 20% O2). After 24 h, cells were moved to hypoxia (5% CO2, 1% O2) for either 1 or 24 h. After the incubation period, the cells were lysed for protein extraction. Other siRNA-treated cells were plated in six-well plates after recovery, incubated in hypoxia for 48 h and used in the proliferation studies described below.

Human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells.

hPASMCs (catalog no. CL-2581, lot no. 7F3558; Lonza) were cultured as previously described (1, 2). Briefly, hPASMCs were grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C in smooth muscle growth media (SmGM; Lonza), which includes smooth muscle basal medium (Lonza), 5% FBS, 0.5 ng/ml human recombinant epidermal growth factor, 2 ng/ml human recombinant fibroblast growth factor, 5 μg/ml insulin, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin. The hPASMCs were used in experiments between the fifth and eighth passages, throughout which no changes in cell morphology were noted. To determine viable cell numbers, equal numbers of hPASMCs (1 × 104) were seeded in each well of a six-well plate and incubated in normoxia for 120 h. Adherent cells were trypsinized and viable cells counted using trypan blue exclusion as previously described (1, 2).

Protein isolation.

Protein was isolated from hPMVECs as previously described (6, 25). Briefly, cells were washed with HBSS, and lysis solution (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, and 10% glycerol) was added. Thirty minutes before use, the following protease inhibitors were added to each milliliter of lysis solution: 0.2 μl aprotinin (10 mg/ml double distilled H2O), 0.5 μl leupeptin (10 mg/ml double distilled H2O), 0.14 μl pepstatin A (5 mg/ml methanol), and 5 μl of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (34.8 mg/ml methanol). The cells were scraped and placed in sterile centrifuge tubes on ice. The supernatant was stored at –70°C for Western blot analysis. Total protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method using a commercially available assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Western blot analysis.

Cell lysates were assayed for EGFR, arginase II, as well as phosphorylated and total amounts of ERK using Western blot analysis as previously described (18, 25). Aliquots of cell lysate were diluted with SDS sample buffer and reducing agent, heated to 80°C for 15 min, and then centrifuged at 10,000 g at room temperature for 2 min. Aliquots of the supernatant were used for SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and blocked overnight in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween (TBS-T) containing 5% nonfat dried milk. The membranes were then incubated with the primary antibody (the following used at 1:1,000: EGFR from Abcam, cat. no. ab2430–1; pERK from Cell Signaling, cat. no. 4376, lot no. 10, and total ERK from BD Transduction, cat. no. 610123, lot no. 47574; and arginase II used at 1:500 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, cat. no. sc-20151, lot no. A2512). The blots were then washed with TBS-T. The membranes were then incubated with the IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody (1:15,000; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Herculus, CA) for 1 h and then washed with TBS-T. The bands of interest were visualized using Luminata Classico Western HRP substrate (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and quantified for densitometry using VisionWork LS Analysis Software (UVP, Upland, CA). To control for protein loading, the blots were then stripped using a stripping buffer (G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO). The blots were reprobed for β-actin (1:10,000; cat. no A1978-200UL, control no. 010M4816; Sigma) as described above.

Proliferation assay.

The proliferation of hPMVECs was determined in six-well plates as previously described (4, 25). Fifty thousand cells were plated into each well of six-well plates. Cells were treated with either siRNA against EGFR or pharmacological inhibitors of EGFR or the MAPK (vehicle (DMSO), AG1478, 1 µM, EGFR; U0126, 10 µM, ERK; SP600125, 20 µM, JNK; or SB203580, 10 µM, p38) and incubated in hypoxia (5% CO2, 1% O2) for 48 h. At the end of the experiments, the cells were removed from the incubator and plates were washed three times with HBSS. After the final wash, 1 ml of trypsin was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 3 min followed by the addition of 2 ml trypsin neutralizing solution. The cells from each well were placed in 15 ml conical tubes. The cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 1,220 g at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and the cells were resuspended in 1 ml of EGM. The cells were mixed 1:1 with trypan blue and viable cells were counted using a hemocytometer.

Transfection of adenoviral vector containing arginase II.

The recombinant adenoviral vectors carrying the human arginase II gene (AdArg2) or the green fluorescent protein gene (AdGFP) under the control of a CMV promoter were constructed using the AdEasy Adenoviral Vector System (Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA) as previously described (4, 6, 15). For virus infection, hPMVECs were seeded and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight and then transfected with AdArg2 or AdGFP at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20 overnight. The cells were washed with PBS and seeded onto six-well plates with 5 × 104 cells per well. U0126 (final concentration: 10 µM) or equal volume of DMSO was added into the media. The cells were incubated for 48 h and viable cell numbers were counted by trypan blue exclusion method.

Statistical analysis.

Values are expressed as the means ± SE. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the data between groups. Significant differences were identified using a Neuman-Keuls post hoc test (SigmaStat 12.5; Jandel Scientific, Carlsbad, CA). Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Hypoxia led to greater EGFR and arginase II protein levels.

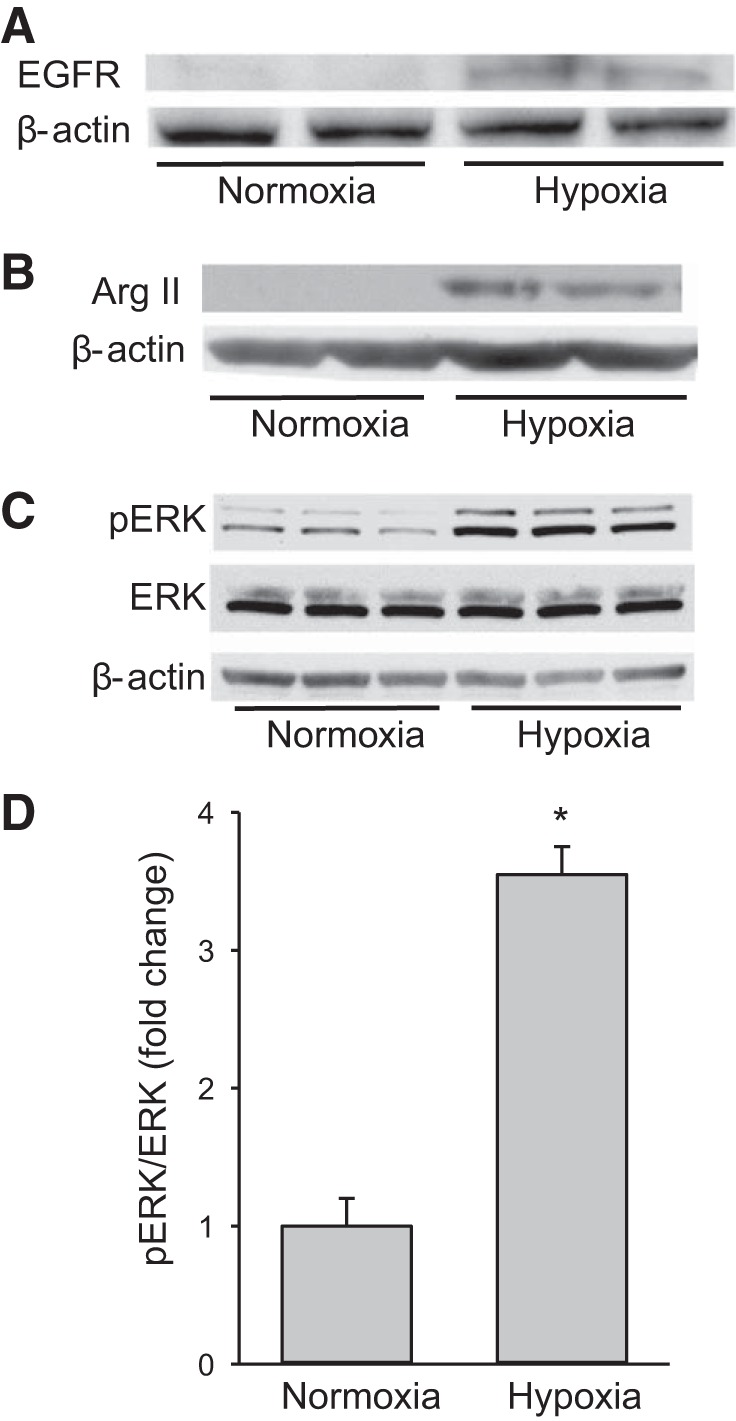

To corroborate our previous findings (25), hPMVECs were incubated in either normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h, and the protein was harvested for Western blot analysis of total EGFR and arginase II. Similar to our previous findings (25), hypoxia led to easily detectable EGFR bands on Western blots (Fig. 1A). Also, consistent with our previous findings (25), hypoxic hPMVECs also demonstrated easily detectable arginase II protein bands, while normoxic cells had nondetectable arginase II protein bands on Western blots (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (hPMVECs) exposed to hypoxia had greater levels of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (pERK), and arginase II protein than cells exposed to normoxia. hPMVECs were incubated in either normoxia (21% O2, 5% CO2) or hypoxia (1% O2, 5% CO2) for 24 h and protein levels of EGFR (A), arginase II (B), or phosphorylated and total ERK (C) were measured. β-Actin was used as a control for protein loading. Representative Western blots are shown from 3 independent experiments. Hypoxia led to easily detectable bands for EGFR and arginase II. Hypoxia increased pERK protein levels without detectably changing total ERK protein levels. D: densitometry data for pERK protein levels normalized to total ERK (n = 3 in each group). Hypoxia led to ~4-fold induction of pERK protein levels in hPVMEC. *P < 0.001, hypoxia different from normoxia.

To examine the effect of hypoxia on ERK in hPMVECs, cells were incubated in normoxia or hypoxia for 24 h and protein was harvested for Western blotting for pERK, ERK, or β-actin. Hypoxic hPMVECs had substantially greater pERK protein levels than did normoxic cells on Western blots, while total ERK and β-actin bands were unchanged by hypoxia (Fig. 1C). Quantification of the pERK levels normalized to total ERK levels demonstrated a nearly fourfold induction of pERK by hypoxia (Fig. 1D).

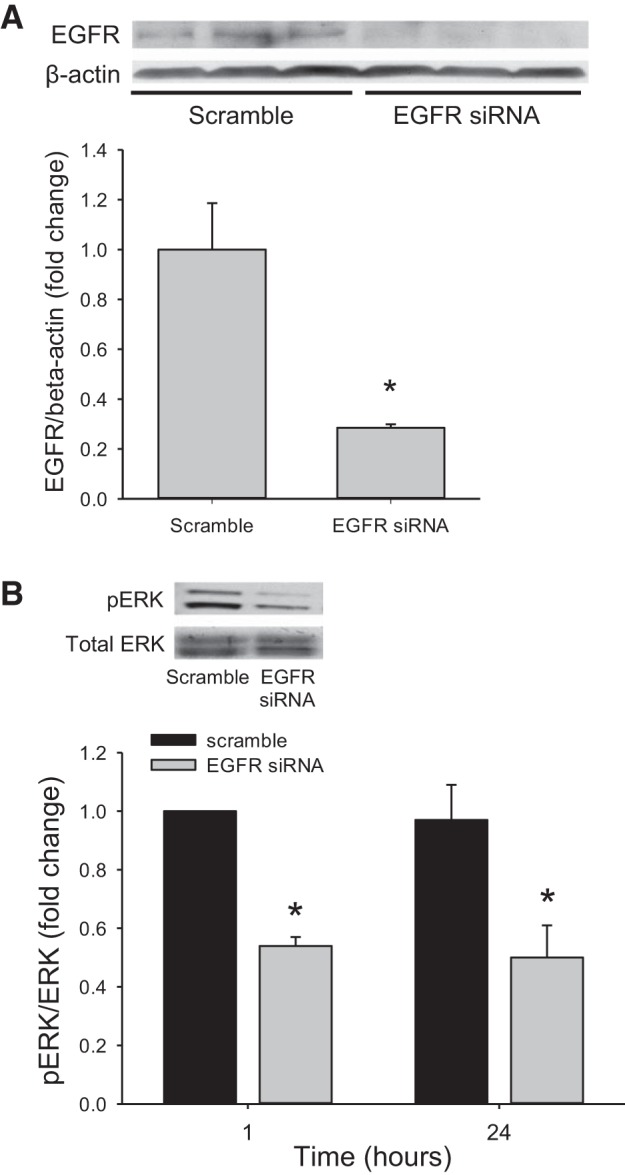

Silencing of EGFR led to lower levels of pERK expression.

To determine the efficacy of siRNA-mediated silencing of EGFR, hPMVECs were transfected with a scrambled siRNA or siRNA against EGFR (EGFR siRNA), incubated in hypoxia for 24 h, and then protein was harvested for Western blotting. Cells transfected with the scrambled siRNA had detectable EGFR protein levels, while cells transfected with EGFR siRNA had no detectable EGFR protein (Fig. 2A). To examine the effect of EGFR silencing on phosphorylation of ERK, hPMVECs were transfected with either a scrambled siRNA or EGFR siRNA for 24 h. The cells were washed, allowed to recover for 24 h and then placed in either normoxia or hypoxia for one or 24 h. Protein was harvested for Western blotting for pERK and total ERK. Cells transfected with the scrambled siRNA had robust pERK protein levels at both one and 24 h of hypoxia, while hypoxic cells transfected with EGFR siRNA had substantially lower levels of pERK than did the scrambled siRNA-transfected hypoxic cells (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

In hypoxia, siRNA-mediated knockdown of EGFR led to lower levels of pERK protein. A: hPMVECs were transfected with either scrambled siRNA or EGFR siRNA and incubated in hypoxia for 24 h and protein levels for EGFR were assessed. Representative Western blots are shown. The bar graph is the densitometry data for EGFR normalized to β-actin (n = 3 in each group) and demonstrates clear knockdown of EGFR protein levels. *P < 0.05, EGFR siRNA different from scrambled. B: hPMVECs were transfected with either scrambled siRNA or EGFR siRNA and incubated in hypoxia for 1 or 24 h and protein levels for pERK were assessed. Representative Western blot for pERK and quantification by densitometry of pERK normalized to total ERK are shown (n = 6–8 for each group). *P < 0.05, EGFR siRNA different from scrambled siRNA.

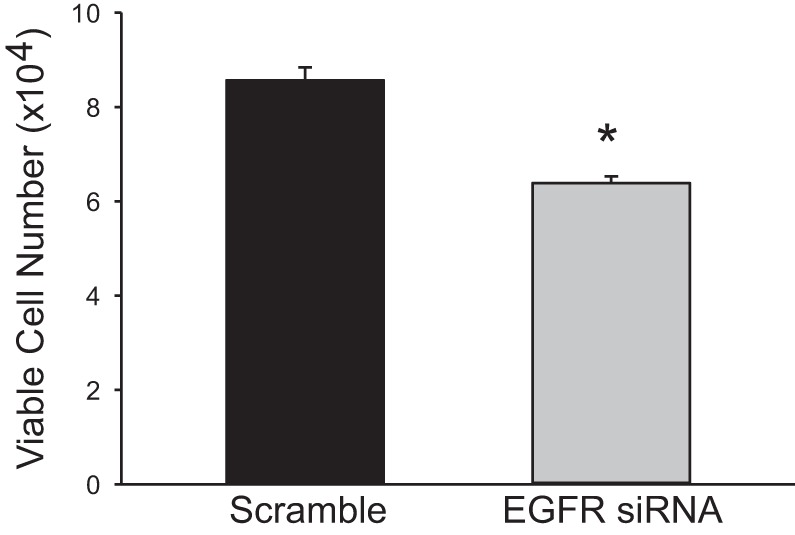

Silencing of EGFR attenuated the hypoxia-induced increase in viable cell numbers.

Given that we have previously shown that EGFR silencing attenuated hypoxia-induced arginase II expression (25) and the above effects of EGFR silencing on the phosphorylation of ERK (Fig. 2B), we examined the effect of EGFR silencing on viable cell numbers. hPMVECs were transfected with EGFR siRNA or a scrambled siRNA for 24 h. Equal numbers of cells were then plated in each well of a six-well plate and placed in hypoxia for 48 h, and viable cell numbers were counted using trypan blue exclusion. After 48 h in hypoxia, the hPMVECs transfected with EGFR siRNA had significantly fewer viable cells than did hPMVECs transfected with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

In hypoxia, siRNA-mediated knockdown of EGFR led to fewer viable cells than in scrambled siRNA-treated cells. hPMVECs were transfected with EGFR siRNA or scrambled siRNA and then equal numbers of hPMVECs were plated on 6-well plates and placed in hypoxia for 48 h (n = 5–8 in each group). Viable cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion. *P < 0.005, EGFR siRNA different from scrambled siRNA.

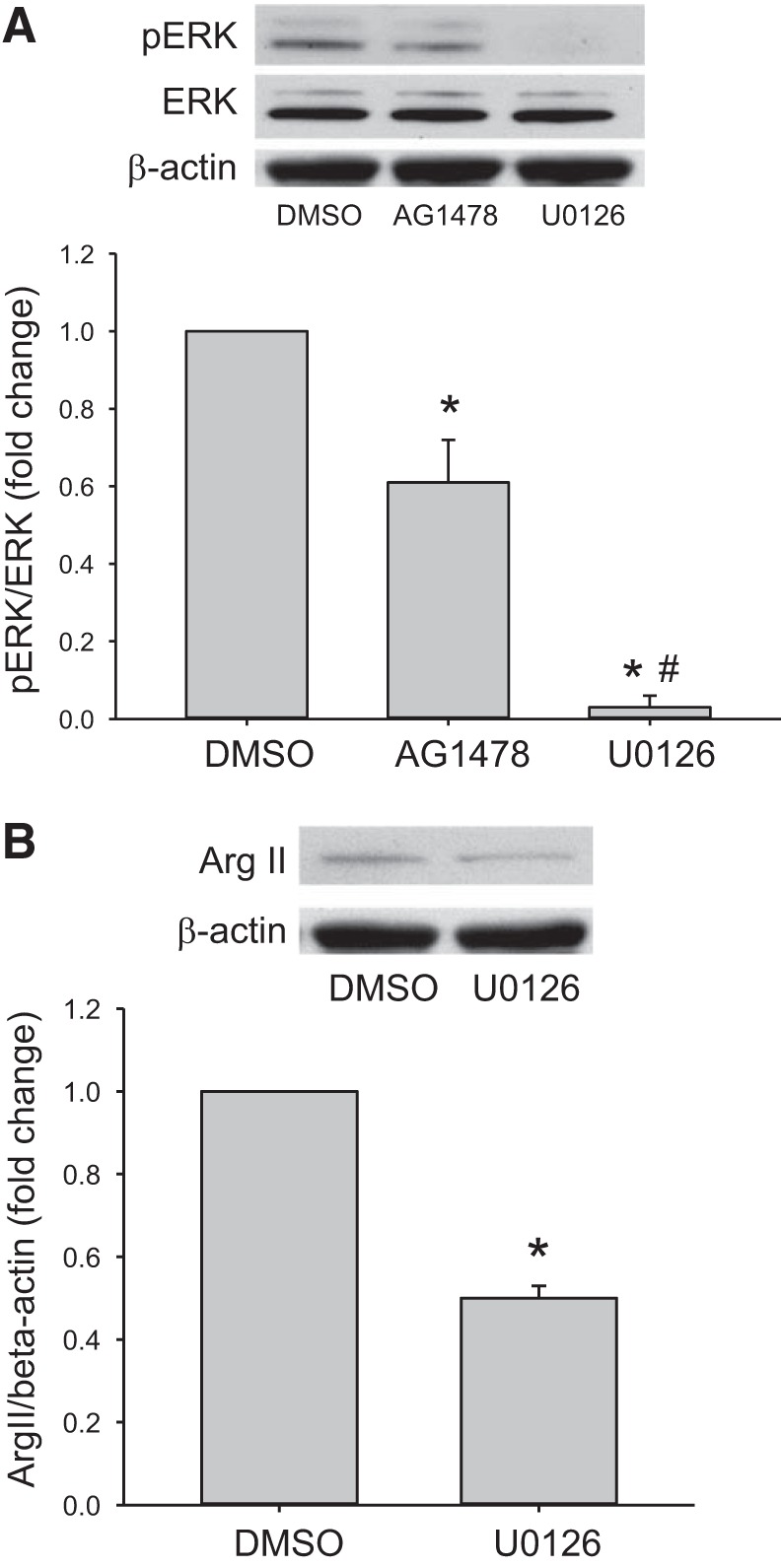

EGFR inhibition attenuated ERK activation.

To examine the effect of pharmacological inhibition of EGFR signaling on the phosphorylation of ERK, hPMVECs were treated with either vehicle, or the putative EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (1 µM) and incubated in hypoxia for 1 h. As a positive control, additional cells were treated with an ERK pathway inhibitor U0126 (10 µM) and placed in hypoxia for 1 h. Cells were harvested for Western blot analysis of pERK and total ERK. Hypoxic cells treated with AG1478 had significantly lower levels of pERK protein than did vehicle treated cells (Fig. 4A). As expected treatment with U0126 prevented pERK expression in hypoxic hPMVECs (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Hypoxic hPMVECs treated with either AG1478 or U0126 had lower levels of pERK and arginase II protein than did hypoxic cells treated with vehicle (DMSO). hPMVECs were treated with either DMSO (vehicle), AG1478 (an EGFR inhibitor; 1 µM), or U0126 (an ERK pathway inhibitor; 10 µM) and incubated in hypoxia for 1 h. Protein was harvested and assessed for pERK and total ERK, or for arginase II and β-actin. A: representative Western blot for pERK and quantification of ERK phosphorylation normalized to ERK (n = 4–6 in each group). B: representative Western blot for arginase II (Arg II) and quantification of arginase II expression normalized to β-actin (n = 6 in each group). *P < 0.05, different from DMSO; #P < 0.01, different from AG1478.

We have previously shown that treatment with AG1478 attenuates hypoxia-induced arginase II protein expression and activity (25). To examine the effect of ERK inhibition on the hypoxic induction of arginase II protein levels, hPMVECs were treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or U0126 (10 µM) and placed in hypoxia for 24 h. Protein was then extracted and assayed for arginase II protein levels using Western blotting. The hypoxic hPMVECs treated with U0126 had significantly lower levels of arginase II than did the hypoxic cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) (Fig. 4B).

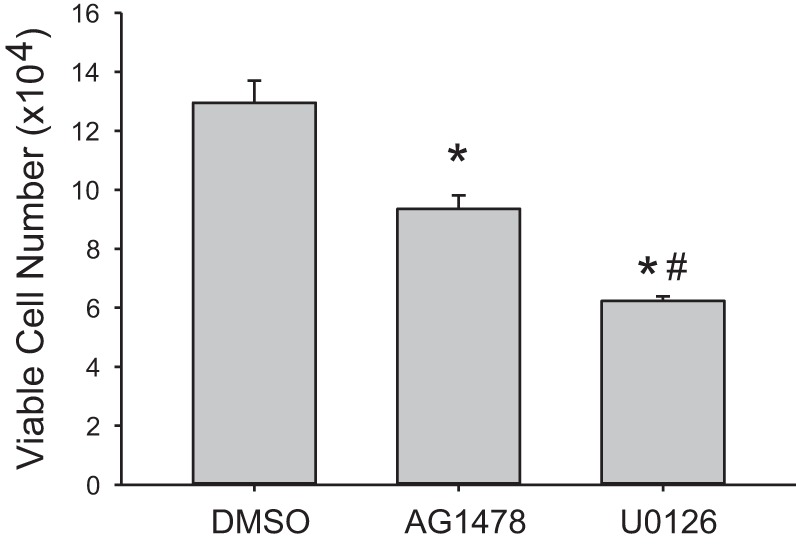

Pharmacological inhibition of ERK attenuated hypoxia-induced cellular proliferation.

Given that AG1478 significantly attenuated phosphorylation of ERK, we examined the effect of AG1478 on viable cell numbers. Equal numbers of hPMVECs were plated in each well of a six-well plate. Cells were treated with either vehicle, AG1478 (1 µM), or U0126 (10 µM). The plates were then placed in hypoxia for 48 h and viable cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion. Inhibition of EGFR using AG1478 significantly attenuated viable cell numbers in hypoxia (Fig. 5). Inhibition of the ERK pathway using U0126 significantly attenuated hypoxia-induced viable cell numbers, and the effect of U0126 on viable cell numbers in hypoxia was greater than the effect of AG1478 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Pharmacologic inhibition of EGFR attenuated hypoxia-induced viable cell numbers. Equal numbers of hPMVECs were plated on 6-well plates; treated with either DMSO (vehicle), AG1478 (1 µM), or U0126 (10 µM); and placed in hypoxia for 48 h. Viable cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion (n = 6–8 in each group). *P < 0.005, different from DMSO; #P < 0.005, different from AG1478.

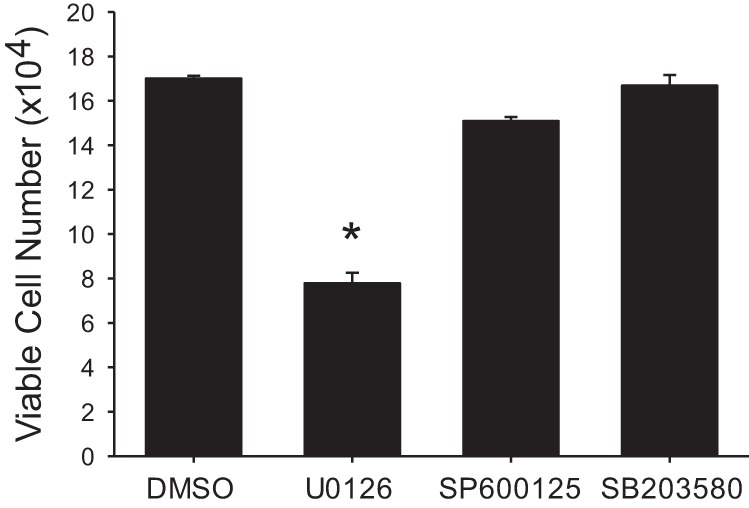

Inhibition of the ERK pathway, but not the JNK or p38 pathway, attenuated hPMVEC proliferation in hypoxia.

To examine the role of all three MAPK pathways in hypoxia-induced proliferation in hPMVECs we utilized the putative inhibitors of JNK (SP600125) and of p38 (SB203580) along with U0126. Equal numbers of hPMVECs were plated in each well of a six-well plate. Cells were treated with either vehicle (DMSO), U0126 (10 µM), SP600125 (20 µM), or SB203580 (10 µM). The plates were then placed in hypoxia for 48 h and viable cells counted using trypan blue exclusion. Viable cell numbers in the hypoxic hPMVECs treated with either the JNK or the p38 inhibitor were not statistically different from viable cell numbers in the vehicle treated hypoxic hPMVECs (Fig. 6). The viable cell numbers in the hypoxic hPMVECs treated with U0126 were significantly lower than viable cell numbers in the vehicle-treated hypoxic cells, while hPMVECs treated with either SP600125 or SB203580 had viable cell numbers similar to vehicle-treated hypoxic cells (Fig. 6). The number of viable cells was significantly lower in the U0126-treated hypoxic cells than in either the SP600125-treated or in the SB203580-treated hypoxic cells (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Only the ERK pathway inhibitor decreased viable cell numbers in hypoxia. Equal numbers of hPMVECs were plated on 6-well plates and treated with either DMSO (vehicle), an ERK pathway inhibitor (U0126; 10 µM), a JNK pathway inhibitor (SP600125; 20 µM), or a p38 pathway inhibitor (SB203580; 10 µM) and placed in hypoxia for 48 h (n = 6–9 in each group). Viable cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion. *P < 0.001, different from all other conditions.

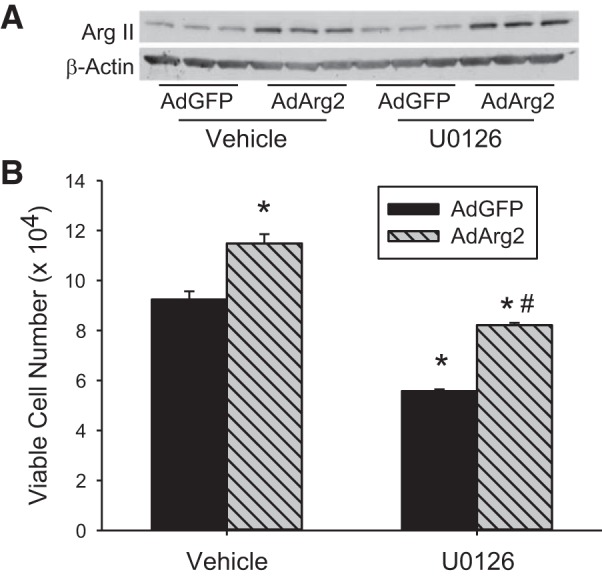

Overexpression of arginase II alleviated the U0126-mediated inhibition on viable cell numbers in hypoxic hPMVECs.

hPMVECs were transfected with an adenoviral vector expressing arginase II (AdArg2) or green fluorescent protein (AdGFP). After 48 h, the cells were washed, treated with either vehicle or U0126, and placed in hypoxia for an additional 48 h. The numbers of viable cells were counted using trypan blue exclusion. Transfection with AdArg2 resulted in greater viable cell numbers than did transfection with AdGFP as demonstrated by the vehicle treated cells (Fig. 7). The ERK pathway inhibitor attenuated hPMVEC proliferation in hypoxia as demonstrated by the lower numbers of viable cells in the AdGFP-transfected, U0126-treated cells than in the AdGFP-transfected cells treated with vehicle (Fig. 7). Overexpression of arginase II reversed the inhibitory effect of U0126 on hypoxic proliferation, such that the viable cell numbers for the AdArg2 transfected cells were not different than viable cell numbers for the AdGFP-transfected, vehicle-treated hPMVECs (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Overexpression of arginase II rescued the U0126-mediated decrease in viable cell numbers in hypoxic hPMVECs. Cells were transfected with either an adenoviral vector containing arginase II (AdArg2) or green fluorescent protein (AdGFP). A: Western blot of Arg II protein demonstrating greater Arg II expression in hPMVECs treated with AdArg2 (n = 6) than in those treated with AdGFP (n = 6) in both vehicle-treated or U0126-treated cells. B: equal number of cells were plated onto 6-well plates and treated with either U0126 or DMSO (vehicle) and placed in hypoxia for 48 h (n = 6 in each group). Viable cell numbers were counted by trypan blue exclusion. *P < 0.001, U0126 different from DMSO same transfection condition; #P < 0.001, AdArg2 different from AdGFP same treatment condition.

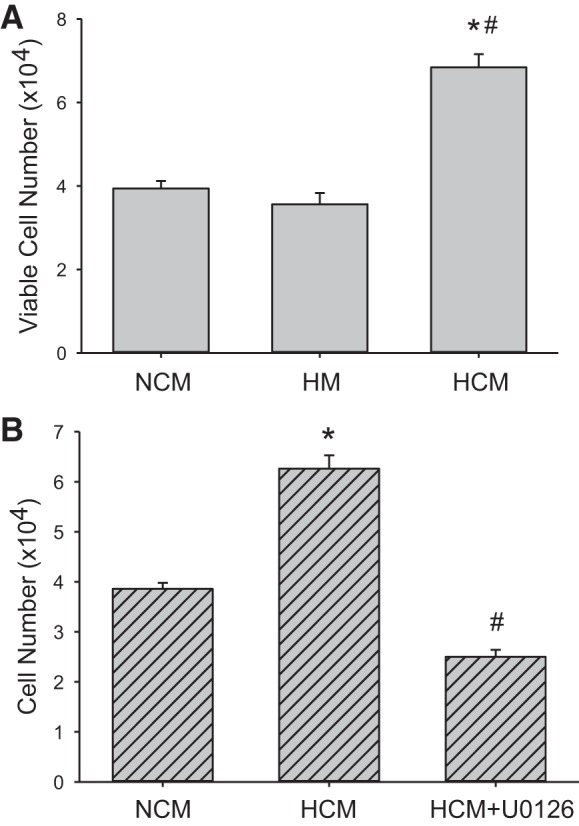

Endothelial cells release ERK-dependent factors into the media that promote an increase in viable numbers in hPASMCs.

Endothelial cells can also release soluble factors that can act on other cells in the vessel wall to promote proliferation and vascular remodeling. We tested the hypothesis that hypoxic hPMVECs would release factors that promoted hPASMC proliferation. We utilized conditioned media from hPMVECs incubated in either normoxia (NCM) or hypoxia (HCM) for 24 h. The conditioned media from the hPMVECs was mixed 1:1 with SmGM and placed on equal numbers of hPASMCs in each well of six-well plates. The plates were incubated for 120 h in normoxia and then viable cell numbers determined. As a control, we also put supplemented endothelial cell media (EBM2) in plates with no hPMVECs and incubated for 24 h in hypoxia, and then mixed this conditioned cell free EBM2 50:50 with SmGM (HM) and placed on equal numbers of hPASMCs and incubated in normoxia for 120 h and viable cell numbers determined. In the conditioned media experiments wherein cells were incubated in normoxia, hPASMC cell number increased by threefold over 120 h with the NCM, while using the hypoxic-conditioned media (HCM) the hPASMC number increased by approximately sixfold over 120 h (P < 0.001 compared with NCM) (Fig. 8A). When the cell free conditioned media was used (HM) the hPASMC cell number increased by approximately threefold over 120 h (Fig. 8A). This suggests that hypoxic hPMVECs released factors into the media that stimulated an increase in hPASMC viable cell numbers.

Fig. 8.

Conditioned media from hypoxic hPMVECs stimulated proliferation in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs). A: hPMVECs were incubated for 24 h in either normoxia (NCM, n = 6) or hypoxia (HCM, n = 6) and the conditioned media were mixed 1:1 with SmGM and placed on equal numbers of hPASMCs (1 × 104 cells per well) in each well of 6-well plates. The hPASMCs were then incubated in normoxia for 120 h and viable cell number determined. As a control conditioned media placed in a cell culture plate with no hPMVECs and incubated for 120 h was used as a control (HM, n = 6). *P < 0.001, HCM different from NCM; #P < 0.001, HCM different from HM. B: to determine the role of ERK in the HCM effects on hPASMCs viable cell numbers after 120 h, the above experiment was repeated except that an additional group of hPMVECs were incubated for 24 h in hypoxia with 10 µM U0126 added (HCM + U0126) to obtain conditioned media; n = 6 for all groups. *P < 0.001, HCM different from NCM; #P < 0.001, HCM + U0126 different from HCM.

To determine if these endothelial factors were dependent on ERK signaling in hypoxic hPMVECs, we repeated the above conditioned media experiments except that we included a group where 10 µM of the ERK inhibitor U0126 were added to the hPMVECs media during the hypoxic incubation (HCM + U0126). Again we found significantly more viable cells after 120 h in the HCM treated hPASMCs incubated in normoxia than in the NCM treated hPASMCs incubated in normoxia (Fig. 8B), and that the HCM effect on viable cell numbers was prevented by U0126 (Fig. 8B).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study in hPMVECs were that 1) hypoxia led to greater EGFR, pERK, and arginase II protein levels; 2) inhibition of EGFR attenuated hypoxia-induced pERK expression and the hypoxia-induced increase in viable cell numbers; 3) inhibition of the ERK pathway attenuated hypoxia-induced arginase II protein induction and cell proliferation; and 4) overexpression of arginase II attenuated the U0126-mediated decrease in viable cell numbers in hypoxic hPMVECs. We also found that conditioned media from hypoxic hPMVECs resulted in greater hPASMC proliferation, which was dependent on ERK signaling in hPMVECs. Taken together, these findings support our hypothesis that in hPMVECs, hypoxia-induced EGFR activation leads to phosphorylation (activation) of ERK ultimately resulting in increased arginase II expression and enhanced cell proliferation.

EGFR is a receptor tyrosine kinase that is expressed in endothelial cells (3, 13, 18) and is essential for regulation of various biological processes including cell proliferation and angiogenesis (7, 11, 13). EGFR is widely expressed in a variety of human tumors including head and neck cancer, breast cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and ovarian cancer (22, 24). Indeed, hypoxia in the center of tumors has been demonstrated to lead to EGFR activation (10). Therefore, EGFR has been targeted as a potential therapy for some types of cancer. In cancer cells, a variety of signaling pathways have been shown to be activated by EGFR, including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) (7, 24). In aortic endothelial cells hydrogen peroxide-mediated activation of EGFR resulted in JNK activation (3). Previously, it has been shown in vascular smooth muscle cells that thrombin activates EGFR via PKC/SRC-mediated activation of ERK (14). Our results demonstrate that hypoxic activation of EGFR in hPMVECs results in phosphorylation of ERK. Taken together it may be that the targets activated downstream of EGFR may depend on the type of stimulus or may be cell type specific. Furthermore, we found that ERK activation was necessary for hypoxia-induced cellular proliferation, since we found that the two other major MAPK families, JNK and p38, were not involved in hypoxia-induced cellular proliferation given that the inhibition of either the JNK or the p38 pathway had little effect on hypoxic viable cell numbers. On the other hand, the ERK pathway inhibitor U0126 prevented the hypoxia-induced increase in viable cell numbers. Our results demonstrate that similar to some cancer cell lines, hypoxia-induced hPMVECs proliferation depends on EGFR-mediated ERK activation.

We have previously shown that hypoxia induces arginase II expression in both hPMVECs and human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (1, 2, 25). There are two isoforms of arginase, arginase I and II, and both isoforms are expressed in endothelial cells. However, in endothelial cells arginase I expression is relatively low and only arginase II is induced by hypoxia and necessary for hypoxia-induced proliferation (18, 25). We have previously found that EGFR was necessary for the hypoxia-induced arginase II expression in hPMVECs (25). In the present study, we demonstrate that hypoxia-induced arginase II expression depends on EGFR-mediated activation of ERK, given that inhibition of ERK activation by U0126 prevented the hypoxia-induced increase in arginase II protein expression. We have previously shown that in bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells and macrophages that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment results in arginase II induction, which limits iNOS-derived NO production (18, 20). Recently, we found that in a macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7) ERK signaling was required for LPS-induced arginase II expression (15). Taken together these results demonstrate a central role of ERK activation in arginase II induction.

We also found in the present study that arginase II induction by the EGFR-ERK pathway was necessary for hypoxia-induced proliferation. Our results demonstrate that treatment with either an EGFR siRNA or ERK pathway inhibitor prevented hypoxia-induced hPMVEC proliferation, suggesting the central role of both EGFR activation and ERK in hypoxia-induced proliferation. The central role of arginase II induction in the EGFR-ERK pathway-mediated hypoxia-induced cellular proliferation is demonstrated in the experiments with arginase II overexpression, wherein inhibiting the ERK pathway again prevented hypoxic proliferation of hPMVECs, while overexpressing arginase II using an adenoviral vector system resulted in the rescue of viable cell numbers in the U0126-treated hypoxic cells, such that the viable cell numbers were not different from the AdGFP-transfected, vehicle-treated cells. We have previously shown in hPVMEC that pharmacological inhibition of arginase prevented hypoxia-induced proliferation in hPMVECs (25). Thus, taken together our studies clearly demonstrate that hypoxia activates EGFR leading to ERK activation, which leads to arginase II induction ultimately resulting in hypoxic cellular proliferation. Inhibition of EGFR prevents hypoxia-induced ERK activation, arginase II induction, and cellular proliferation. Likewise, inhibition of ERK prevents hypoxia-induced arginase II expression and cellular proliferation. As we have previously demonstrated, arginase II inhibition prevents hypoxic cellular proliferation in hPMVECs (25). Furthermore, overexpression of arginase II, but not green fluorescent protein, rescues the U0126 suppression of hypoxic cellular proliferation.

Although our data demonstrate a central role for EGFR activation in hypoxic cellular proliferation, it remains unclear the exact mechanism by which EGFR is activated in these hypoxic hPMVECs. EGFR can be activated by ligand binding, and its preferred ligand is epidermal growth factor (EGF). When activated by ligand binding, two EGFR moieties dimerize resulting in trans-phosphorylation that enables interactions with signaling molecules (11). We have previously shown that EGF treatment of bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells results in EGFR phosphorylation and activation (18). In some forms of cancer, EGFR activation has been shown to occur without ligand binding and preventing this transactivation has been shown to decrease tumor size (5). This transactivation may be through G protein-coupled receptors or other cellular receptors leading to ectodomian shedding (13). The exact mechanism underlying hypoxic EGFR activation in hPMVECs will require further study.

In conclusion, we found that hypoxia-induced proliferation in hPMVECs depends on EGFR-mediated ERK activation leading to arginase II protein expression. Inhibiting EGFR activation using either siRNA or a small molecule inhibitor prevented hypoxia-induced pERK and arginase II expression, as well as the hypoxia-induced increase in viable cell numbers. Inhibition of the ERK pathway using U0126 attenuated arginase II protein induction and cell proliferation in response to hypoxia, and the U0126-mediated attenuation of hypoxic cell proliferation could be attenuated by overexpressing arginase II. We show that the other MAPKs, JNK and p38, are not involved in the hypoxia-induced cellular proliferation in hPMVECs. These data are consistent with the idea that in hPMVECs, hypoxia leads to arginase-mediated cell proliferation, as well as release of pro-proliferative factors that can act on vascular smooth muscle cells, through a signal transduction network that requires EGFR-mediated ERK activation. Given that there are no selective arginase II inhibitors at this time, understanding the signaling cascade leading to arginase II induction is imperative for identifying potential therapeutic targets for PH wherein cellular proliferation is a hallmark, as is true in most causes of adult PH associated with vascular remodeling and/or plexiform lesions. Our findings demonstrate that further studies are warranted to explore the potential of FDA-approved EGFR inhibitors in the treatment and/or prevention of PH, particularly WHO Group 3 Pulmonary Hypertension in adult diseases such as COPD.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.A.W. and Y.J. performed experiments; H.A.W., Y.J., and L.D.N. analyzed data; H.A.W., L.G.C., B.C., Y.L., and L.D.N. interpreted results of experiments; H.A.W. and L.D.N. prepared figures; H.A.W. drafted manuscript; H.A.W., Y.J., L.G.C., B.C., Y.L., and L.D.N. edited and revised manuscript; H.A.W., Y.J., L.G.C., B.C., Y.L., and L.D.N. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen B, Calvert AE, Cui H, Nelin LD. Hypoxia promotes human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation through induction of arginase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol : L1151–L1159, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00183.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen B, Calvert AE, Meng X, Nelin LD. Pharmacologic agents elevating cAMP prevent arginase II expression and proliferation of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol : 218–226, 2012. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0015OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen K, Vita JA, Berk BC, Keaney JF Jr. c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation by hydrogen peroxide in endothelial cells involves SRC-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation. J Biol Chem : 16045–16050, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chicoine LG, Stenger MR, Cui H, Calvert A, Evans RJ, English BK, Liu Y, Nelin LD. Nitric oxide suppression of cellular proliferation depends on cationic amino acid transporter activity in cytokine-stimulated pulmonary endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol : L596–L604, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00029.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med : 1160–1174, 2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui H, Chen B, Chicoine LG, Nelin LD. Overexpression of cationic amino acid transporter-1 increases nitric oxide production in hypoxic human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol : 796–803, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Luca A, Carotenuto A, Rachiglio A, Gallo M, Maiello MR, Aldinucci D, Pinto A, Normanno N. The role of the EGFR signaling in tumor microenvironment. J Cell Physiol : 559–567, 2008. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai Z, Li M, Wharton J, Zhu MM, Zhao YY. Prolyl-4 hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) deficiency in endothelial cells and hematopoietic cells induces obliterative vascular remodeling and severe pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice and humans through hypoxia-inducible factor-2α. Circulation : 2447–2458, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferns SJ, Wehrmacher WH, Serratto M. Pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension–a review. Compr Ther : 81–90, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franovic A, Gunaratnam L, Smith K, Robert I, Patten D, Lee S. Translational up-regulation of the EGFR by tumor hypoxia provides a nonmutational explanation for its overexpression in human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA : 13092–13097, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702387104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller SJ, Sivarajah K, Sugden PH. ErbB receptors, their ligands, and the consequences of their activation and inhibition in the myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol : 831–854, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.02.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao Y, Cornfield DN, Stenmark KR, Thébaud B, Abman SH, Raj JU. Unique aspects of the developing lung circulation: structural development and regulation of vasomotor tone. Pulm Circ : 407–425, 2016. doi: 10.1086/688890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higashiyama S, Iwabuki H, Morimoto C, Hieda M, Inoue H, Matsushita N. Membrane-anchored growth factors, the epidermal growth factor family: beyond receptor ligands. Cancer Sci : 214–220, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh HL, Tung WH, Wu CY, Wang HH, Lin CC, Wang TS, Yang CM. Thrombin induces EGF receptor expression and cell proliferation via a PKC(delta)/c-Src-dependent pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol : 1594–1601, 2009. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.185801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin Y, Liu Y, Nelin LD. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase mediates expression of arginase II but not inducible nitric-oxide synthase in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J Biol Chem : 2099–2111, 2015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.599985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Shepherd EG, Nelin LD. MAPK phosphatases–regulating the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol : 202–212, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nri2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrell NW, Adnot S, Archer SL, Dupuis J, Jones PL, MacLean MR, McMurtry IF, Stenmark KR, Thistlethwaite PA, Weissmann N, Yuan JX, Weir EK. Cellular and molecular basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol , Suppl: S20–S31, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelin LD, Chicoine LG, Reber KM, English BK, Young TL, Liu Y. Cytokine-induced endothelial arginase expression is dependent on epidermal growth factor receptor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol : 394–401, 2005. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelin LD, Stenger MR, Malleske DT, Chicoine LG. Vascular arginase and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rev : 242–249, 2007. doi: 10.2174/157340207782403881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelin LD, Wang X, Zhao Q, Chicoine LG, Young TL, Hatch DM, English BK, Liu Y. MKP-1 switches arginine metabolism from nitric oxide synthase to arginase following endotoxin challenge. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol : C632–C640, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00137.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rai PR, Cool CD, King JA, Stevens T, Burns N, Winn RA, Kasper M, Voelkel NF. The cancer paradigm of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med : 558–564, 2008. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200709-1369PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salomon DS, Brandt R, Ciardiello F, Normanno N. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol : 183–232, 1995. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)00144-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simonneau G, Robbins IM, Beghetti M, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Denton CP, Elliott CG, Gaine SP, Gladwin MT, Jing ZC, Krowka MJ, Langleben D, Nakanishi N, Souza R. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol , Suppl: S43–S54, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka Y, Terai Y, Tanabe A, Sasaki H, Sekijima T, Fujiwara S, Yamashita Y, Kanemura M, Ueda M, Sugita M, Franklin WA, Ohmichi M. Prognostic effect of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations and the aberrant phosphorylation of Akt and ERK in ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Ther : 50–57, 2011. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.1.13877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toby IT, Chicoine LG, Cui H, Chen B, Nelin LD. Hypoxia-induced proliferation of human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells depends on epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase activation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol : L600–L606, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00122.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuder RM, Abman SH, Braun T, Capron F, Stevens T, Thistlethwaite PA, Haworth SG. Development and pathology of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol , Suppl: S3–S9, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu W, Erzurum SC. Endothelial cell energy metabolism, proliferation, and apoptosis in pulmonary hypertension. Compr Physiol : 357–372, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao L, Luo H, Li X, Li T, He J, Qi Q, Liu Y, Yu Z. Exosomes derived from human pulmonary artery endothelial cells shift the balance between proliferation and apoptosis of smooth muscle cells. Cardiology : 43–53, 2017. doi: 10.1159/000453544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]