Abstract

Background

The role of the intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) in acute decompensated heart failure (HF) with cardiogenic shock (CS) is largely undefined. We sought to assess the hemodynamic and clinical response to IABP in chronic HF patients with CS and identify predictors of response to this device.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed all patients undergoing IABP implantation from 2011–2016 at our institution to identify chronic HF patients with acute decompensation and CS (cardiac index <2.2 L/min/m2 and systolic blood pressure <90mmHg or need for vasoactive medications to maintain this). Clinical deterioration on IABP was defined as failure to bridge to either discharge on medical therapy or durable heart replacement therapy (HRT; durable left ventricular assist device or heart transplant) with IABP alone.

Results

We identified 132 chronic HF patients with IABP placed after decompensation with hemodynamic evidence of CS. Overall 30-day survival was 84.1% and 78.0% of patients were successfully bridged to HRT or discharge without need for escalation of device support. The complication rate during IABP support was 2.3%. Multivariable analysis identified ischemic cardiomyopathy (OR 3.24, 95% CI 1.16–9.06; p=0.03) and pulmonary artery pulsatility index (PAPi) < 2.0 (OR 5.04, CI 1.86–13.63; p=0.001) as predictors of clinical deterioration on IABP.

Conclusions

Overall outcomes with IABP in acute decompensated chronic HF patients are encouraging, and IABP is a reasonable first-line device for chronic HF patients in CS. Baseline right ventricular function as measured by PAPi is an important predictor of outcomes with IABP in this population.

Introduction

Chronic heart failure (HF) affects more than 5.5 million people in the United States with an estimated 600,000–800,000 patients living with advanced HF (NYHA Class IIIb–IV).1 While significant improvements in both medical and device-based therapies have improved the prognosis of chronic HF,2,3 episodes of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) may result in rapid deterioration and substantially worsen prognosis. Cardiogenic shock (CS) represents ADHF in its most severe form and is broadly defined as severe cardiac dysfunction resulting in impaired end-organ perfusion. Although inotropes and vasopressors remain first-line therapies for CS, they have significant adverse side effects (e.g. arrhythmia) and may be insufficient to counteract this process.4

Temporary mechanical circulatory support devices (tMCSD) are often utilized in CS refractory to medical therapy in an effort to stabilize patients sufficiently to allow for either removal of tMCSD and discharge from the hospital or successful bridge to heart replacement therapy (HRT; e.g. durable left ventricular assist device [LVAD] or orthotopic heart transplantation [OHT]). Percutaneous tMCSD options include intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), micro-axial percutaneous LVADs, extracorporeal centrifugal flow LVADs, and extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).5 Of these, the intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) is the most widely used by a substantial margin, largely due to its widespread availability, ease of insertion, and low complication rate.6

Despite decades of IABP experience, its appropriate clinical role in CS remains poorly defined, largely due to limited evidence to guide its use. The largest randomized, controlled trial in patients with CS demonstrated neither benefit nor harm with IABP use in CS following acute myocardial infarction (AMI).7 Findings of this study have led to a paradigm shift away from routine IABP use in these patients. However, chronic HF patients with acute decompensation and CS represent a unique physiological phenotype compared to AMI patients, which may lead to a differential response to device therapy. The objectives of our study were to assess the clinical and hemodynamic response to IABP in chronic HF patients with CS and identify predictors of clinical deterioration on IABP therapy in this population.

Methods

Study Population

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all patients in the cardiac care unit who underwent IABP implantation at our institution from January, 2011 to April, 2016. All patients 18 years or older with chronic systolic HF (LVEF < 40% for > 6 months) who underwent IABP placement for acute on chronic decompensated HF with hemodynamic evidence of CS were included in our cohort. Hemodynamic evidence of CS was defined as pre-IABP cardiac index (CI) < 2.2 L/min/m2 and either systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or need for vasoactive medications to achieve this. Exclusion criteria were 1) diagnosis of AMI during the index hospitalization, 2) IABP placement following cardiac surgery, 3) concurrent support with another tMCSD at the time of IABP implantation (e.g. ECMO), 4) prior OHT, and 5) lack of pre-implant hemodynamic data. The study was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

Demographic data were collected including co-morbidities, etiology of cardiomyopathy (ischemic vs. non-ischemic), and echocardiographic parameters. Hemodynamic data included measurements made by pulmonary artery (PA) catheter including cardiac output (CO) and CI (Fick method) as well as the pulmonary artery pulsatility index (PAPi = [Systolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure – Diastolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure]/Right Atrial Pressure). Laboratory data included serum creatinine, lactate, hemoglobin, and baseline eGFR (MDRD Formula). We defined hemodynamic “super-responders” as those patients with increase in CO in the top quartile of the cohort.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was clinical deterioration despite IABP therapy. Patients were considered to have been stabilized on IABP if they were 1) weaned from IABP and discharged from the hospital on medical therapy, or 2) bridged to durable HRT on IABP alone and survived to discharge. Patients not meeting these criteria (e.g. those who died or required escalation to another tMCSD device during IABP support) were considered to have clinical deterioration despite IABP. Secondary outcomes included 30-day mortality and immediate hemodynamic response (change in CO and CI, mean arterial pressure [MAP], and mean PA pressure). Adverse events were defined as the following: 1) Bleeding: the need for packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusion during IABP support related to access site bleeding or the need for > 2 PRBC transfusion during IABP support not related to access site bleeding; 2) IABP malfunction: any pump malfunction requiring unplanned catheter exchange or removal; 3) Vascular complication: limb ischemia which did not resolve with IABP removal or required endovascular or surgical intervention; and 4) Embolic events: presence of new symptoms of an embolic event (e.g. neurological deficit or visceral infarction) temporally related to IABP use.

Statistical methods

Continuous variables were compared with the Student’s T-test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test, as appropriate, and categorical variables were compared using chi-squared tests. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies, and continuous variables are reported as means ± standard deviation or medians with interquartile range where appropriate. Logistic regression was used to identify pre-implant variables associated with clinical and hemodynamic response to IABP insertion. Variables with a p-value <0.1 in univariable analysis and those felt to be clinically important with respect to the primary outcome (e.g. age and gender) were included in a multivariable model. Collinear variables were excluded. All analyses were performed using STATA Statistical Software, Version 15.0 (College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP).

Results

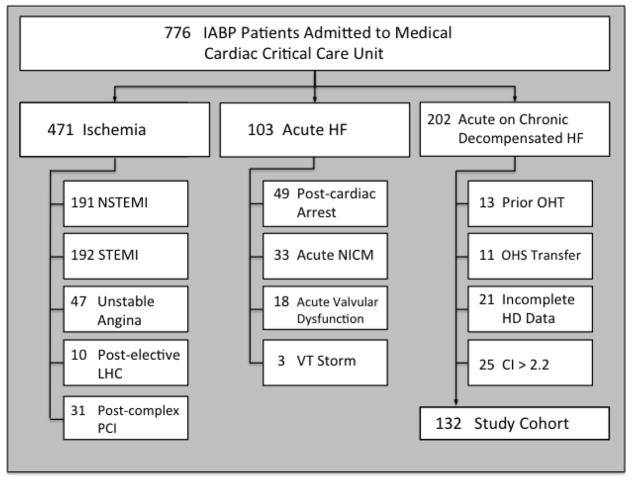

Figure 1 details IABP use at our institution during the study period for all indications, not solely for ADHF. In total, 776 patients in the cardiac critical care unit received an IABP during the study period. The primary indications for IABP implantation were active myocardial ischemia (430 patients, 55.4%), acute HF (e.g. fulminant myocarditis; 33 patients, 4.3%), and acute on chronic decompensated HF (202 patients, 26.0%). Of the 202 patients receiving IABP for ADHF, 70 were excluded for the following reasons: prior OHT (n=13), transferred from outside hospitals with IABP already in place (n=11), incomplete pre-implant hemodynamic data (n=21), and pre-implant CI > 2.2 L/min/m2 (n=25). Our final cohort included 132 chronic systolic HF patients receiving IABP for ADHF with hemodynamic evidence of CS (Figure 1). All patients had insertion of the IABP in the femoral position with the exception of 1 who had the device placed in the axillary position.

Figure 1.

Patient selection flowchart. CI, cardiac index; HD, hemodynamic; HF, heart failure; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; LHC, left-heart catheterization; NICM, non-ischemic cardiomyopathy; NSTEMI, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; OHT, orthotopic heart transplant; OSH, outside hospital; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; VT, ventricular tachycardia

Baseline characteristics

The study cohort’s baseline characteristics are represented in Table 1. Baseline CI was 1.56 ± 0.37 L/min/m2 and mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 29.5 ± 8.3 mmHg. Mean serum lactate was 2.5 ± 2.5 mmol/L and mean eGFR was 47.6 ± 21.9 ml/min/1.73m2. The mean duration of cardiomyopathy in the whole cohort was 81.5 ± 65.5 months. In the clinical stabilization cohort, it was 84.3 ± 64.3 months whereas in the clinical deterioration cohort it was 73.3 ± 69.0 months (p = 0.42). When compared to patients stabilized on IABP, those with clinical deterioration were more likely to have an ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM; 58.8% vs 28.6%, p=0.002) and to be receiving vasopressor medications at the time of implantation (44.1% vs 22.4%, p=0.02). Comparison of baseline hemodynamics revealed that patients with clinical deterioration had lower diastolic blood pressure (60.8 mmHg vs 65.3 mmHg, p=0.04), lower MAP (72.3 mmHg vs 76.7 mmHg, p=0.04), higher CVP (18.9 mmHg vs 13.1 mmHg, p=0.0001), lower PAPi (1.86 vs 3.39, p=0.03), and smaller left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (6.56 cm vs 7.08, p=0.02). When comparing patients with ICM and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM), filling pressures were similar between these two groups (CVP 15.2 ± 7.7 mmHg vs. 14.3 ± 6.9 mmHg, respectively, p = 0.50; mean PA pressure 38.9 ± 10.2 mmHg vs. 37.4 ± 8.8 mmHg, respectively, p = 0.39) though patients with NICM had a lower cardiac index at baseline (1.65 ± 0.36 L/min/m2 vs. 1.51 ± 0.34 L/min/m2, p=0.03).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for Chronic HF Patients with IABP Placed for Cardiogenic Shock. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LV, left ventricle. LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PA, pulmonary artery; RV, right ventricle.

| All (n=132) | Clinical stabilization (n=98) | Clinical deterioration (n=34) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age | 61.2 ± 13.0 | 60.2 ± 12.5 | 64.1 ± 14.2 | 0.13 |

| Male gender (%) | 111 (84.1) | 82 (83.7) | 29 (85.3) | 0.84 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.93 ± 0.25 | 1.95 ± 0.23 | 1.85 ± 0.28 | 0.06 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 44 (33.3) | 29 (29.6) | 15 (44.1) | 0.12 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy (%) | 48 (36.4) | 28 (28.6) | 20 (58.8) | 0.002 |

|

| ||||

| Hemodynamic data | ||||

|

| ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 98.4 ± 14.6 | 99.5 ± 15.3 | 95.3 ± 11.8 | 0.16 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 64.2 ± 10.9 | 65.3 ± 11.3 | 60.8 ± 9.1 | 0.04 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 75.6 ± 10.6 | 76.7 ± 11.1 | 72.3 ± 8.6 | 0.04 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 93.0 ± 19.3 | 91.5 ± 17.5 | 97.3 ± 23.5 | 0.14 |

| Baseline cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 1.56 ± 0.37 | 1.54 ± 0.35 | 1.64 ± 0.37 | 0.14 |

| Central venous pressure (mmHg) | 14.6 ± 7.2 | 13.1 ± 6.6 | 18.9 ± 6.9 | <0.0001 |

| PA systolic pressure (mmHg) | 56.6 ± 14.0 | 56.3 ± 14.3 | 57.2 ± 13.2 | 0.75 |

| PA diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 28.2 ± 8.1 | 27.9 ± 8.2 | 28.9 ± 7.9 | 0.55 |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 37.9 ± 9.3 | 37.5 ± 9.3 | 39.1 ± 9.4 | 0.41 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (mmHg) | 29.5 ± 8.3 | 28.8 ± 8.5 | 31.7 ± 7.6 | 0.28 |

| Cardiac power index | 0.26 ± 0.07 | 0.26 ± 0.07 | 0.26 ± 0.06 | 0.98 |

| PA pulsatility index | 2.97 ± 3.39 | 3.39 ± 3.79 | 1.86 ± 1.49 | 0.03 |

| LV stroke work index | 12.13 ± 4.40 | 12.75 ± 4.44 | 10.39 ± 3.81 | 0.11 |

| RV stroke work index | 5.61 ± 3.00 | 5.84 ± 3.08 | 4.98 ± 2.73 | 0.16 |

| Inotropes (baseline % on] | 115 (87.1) | 84 (85.7) | 31 (91.2) | 0.41 |

| Pressors (baseline % on] | 37 (28.0) | 22 (22.4) | 15 (44.1) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||

| Additional data | ||||

|

| ||||

| Baseline eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 47.6 ± 21.9 | 48.1 ± 20.1 | 46.3 ± 26.8 | 0.69 |

| Baseline lactate, serum (mmol/L) | 2.5 ± 2.5 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 3.5 | 0.07 |

| LVEF (%) | 18.0 ± 8.9 | 17.6 ± 9.4 | 19.0 ± 7.0 | 0.38 |

| LVEDD (cm) | 6.95 ± 1.14 | 7.08 ± 1.13 | 6.56 ± 1.12 | 0.02 |

| Mitral regurgitation (mod-sev) | 90 (68.2) | 71 (72.4) | 19 (55.9) | 0.07 |

Concomitant medical therapy

The mean blood pressure in the entire cohort was 98/64mmHg and 37 (28.0%) of these patients were already on at least 1 vasopressor agent. The number of patients receiving vasopressors and the mean doses used were as follows: 1 (0.8%) patient was receiving phenylephrine at 150 mcg/min, 4 (3.0%) were receiving norepinephrine at a mean dose of 13.9 ± 12.5 mcg/min, 26 (19.7%) were receiving vasopressin at a mean dose of 2.4 ± 1.4 U/hr, and 1 (0.8%) patient was receiving epinephrine at a dose of 1mcg/min. Inotropes were used frequently, with 115 (87.1%) receiving at least one inotrope at the time of IABP insertion. The number of patients receiving inotropes and the mean doses used were as follows: 72 (54.5%) patients were receiving milrinone at a mean dose of 0.31 ± 0.12 mcg/kg/min, 45 (34.1%) were receiving dobutamine at a mean dose of 4.6 ± 2.0 mcg/kg/min, and 23 (17.4%) were receiving dopamine at a mean dose of 2.9 ± 2.0 mcg/kg/min.

Clinical outcomes

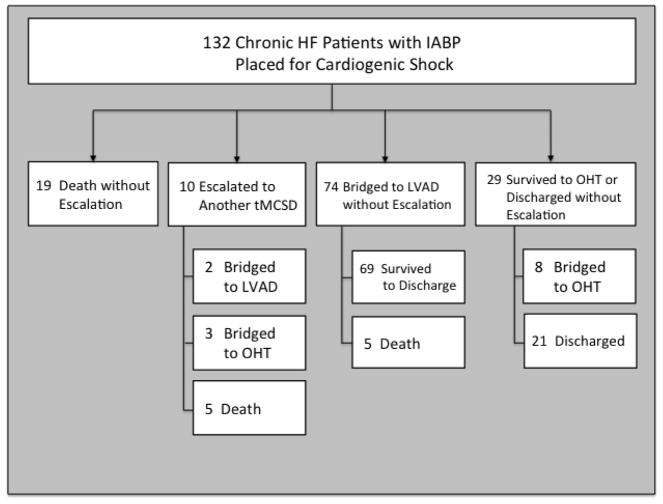

The median time on IABP support for the entire cohort was 96.0 hours (IQR 48.0 –144.0). For the clinical stabilization cohort, it was 96.0 hours (IQR 49.0 –132.0) and for the clinical deterioration cohort it was 84.0 hours (IQR 44.0 – 235.0; p = 0.49). Those who went on to LVAD or OHT had a median time on IABP support of 110.5 hours (IQR 48 –168). Thirty-day survival and survival to discharge were 84.1% and 78.0%, respectively. The primary outcome of clinical deterioration occurred in 34 (25.8%) patients while 98 (74.2%) had stabilization on IABP. Among the latter group, 21 (21.4%) were discharged from the hospital on medical therapy alone, 69 (70.4%) were bridged to durable LVAD, and 8 (8.2%) were bridged to OHT. Of the 34 patients with clinical deterioration on IABP, 19 (55.9%) died or were discharged to hospice without needing another tMCSD, 10 (29.4%) were escalated to another tMCSD for further stabilization, and 5 (14.7%) died after having been bridged to durable LVAD on IABP alone. Of those receiving another tMCSD (ECMO or surgically implanted short-term ventricular assist device), 2 (20.0%) were ultimately bridged to durable LVAD, 3 (30.0%) to OHT, and 5 (50.0%) died (Figure 2). At our institution, we typically consider implantation of another more powerful device if there are signs of persistent shock or the need for substantial escalation of pharmacotherapy to maintain adequate CO, blood pressure, and end-organ function. The median time to escalation for those who required a more powerful device was 48.0 hours (IQR 38.0 – 91.0). Among those in the stabilization cohort, 22 (22.4%) had a significant increase in vasopressor or inotrope requirement (defined as addition of one of these agents or >25% increase in the doses administered) while 13 (38.2%) in the deterioration group had a significant increase in these medications (p = 0.07).

Figure 2.

Study cohort clinical outcomes. HD, hemodynamic; HF, heart failure; HRT, heart replacement therapy; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; LVAD, left-ventricular assist device; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; OHT, orthotopic heart transplant

Immediate hemodynamic response

The median duration of time between pre– and post–implant hemodynamic measurement was 5.0 hours (IQR 4.0 – 9.0). For those who clinically stabilized the median was 5.0 hours (IQR 4.0 – 9.0) and for those with clinical deterioration it was 5.5 hours (IQR 3.0 –10.0; p = 0.96). The mean increase in CO and CI following IABP implantation was 0.51 L/min (IQR 0.08, 0.98) and 0.26 L/min/m2 (IQR 0.01, 0.48), respectively. The change in mean PA pressure was −5 mmHg (IQR −9, 1). The mean change in MAP was −2.0 mmHg (IQR −10.0, 7.3). Patients stabilized on IABP had a change in CO of +0.54 L/min (IQR 0.08, 1.01) while those with further clinical deterioration had a change in CO of +0.30 L/min (IQR 0, 0.83) (p=0.31). No significant differences existed between the groups with regard to mean PA pressure change (clinical stabilization group: −5mmHg [IQR −11, 0] vs. clinical deterioration group: −5mmHg [IQR −8, −1], p=0.67) or change in MAP (clinical stabilization group: −2.8mmHg [IQR −11.5, 7.2] vs. clinical deterioration group: −1.2mmHg [IQR −7.3, 7.3], p=0.38) following IABP implantation.

Predictors of clinical response

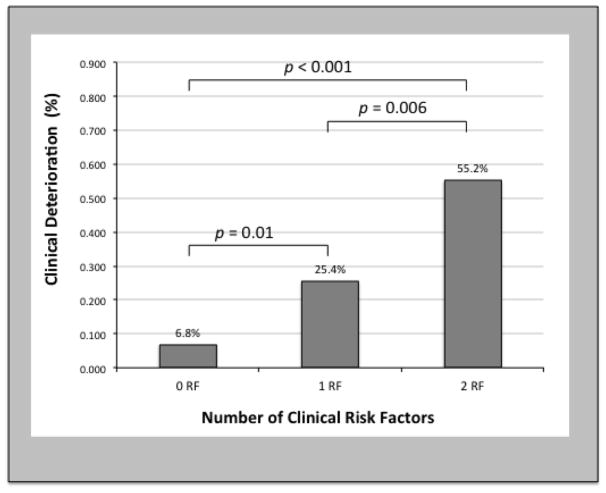

Univariable analysis identified ICM (OR 3.57, CI 1.59 – 8.04; p=0.002), vasopressor use at the time of implantation (OR 2.73; 95% CI 1.19–6.23; p=0.02), higher CVP (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.06–1.21; p < 0.001), and lower PAPi (OR 5.14; 95% CI 2.04–12.94; p = 0.001) as predictors of clinical deterioration on IABP. In multivariable analysis, ICM (OR 3.24; 95% CI 1.16–9.06; p=0.03) and PAPi < 2.0 (OR 5.04; 95% CI 1.86–13.63; p=0.001) were independent predictors of clinical deterioration on IABP (Table 2). This cut point for PAPi was guided by the cohort’s median value and prior reports of this index as a predictor of outcomes in multiple phenotypes of shock8–10. Patients with 0, 1, or 2 of these risk factors experienced rates of clinical deterioration of 6.8%, 25.4%, and 55.2% (Figure 3, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Analysis of Potential Predictors of Inadequate Response to IABP Therapy. LV, left ventricle. PA, pulmonary artery.

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Odds Ratio (95%CI) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Age | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | 0.14 | 0.97 (0.96–1.04) | 0.85 |

| Male | 1.13 (0.38–3.37) | 0.82 | 0.73 (0.21–2.58) | 0.63 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 3.57 (1.59–8.04) | 0.002 | 3.24 (1.16–9.06) | 0.03 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 0.96 (0.92–1.0) | 0.04 | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 0.58 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 1.02 (0.99–1.03) | 0.14 | ||

| Baseline cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 2.32 (0.75–7.15) | 0.14 | ||

| Central venous pressure (mmHg) | 1.13 (1.06–1.21) | <0.001 | ||

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.4 | ||

| Cardiac power index | 1.10 (0.01–490.2) | 0.98 | ||

| PA pulsatility index <2.0 | 5.14 (2.04–12.94) | 0.001 | 5.04 (1.86–13.63) | 0.001 |

| LV stroke work index | 0.86 (0.71–1.04) | 0.12 | ||

| RV stroke work index | 0.90 (0.78–1.04) | 0.16 | ||

| Multiple inotropes (>2) | 1.05 (0.48–2.29) | 0.91 | ||

| Pressors (≥1) | 2.73 (1.19–6.23) | 0.02 | 2.24 (0.81–6.18) | 0.12 |

| Mitral regurgitation (mod-sev) | 0.48 (0.21–1.08) | 0.08 | 0.49 (0.19–1.27) | 0.14 |

Figure 3.

Predictors of clinical response. Association between identified risk factors and inadequate clinical response leading to death or device escalation. RF, risk factor.

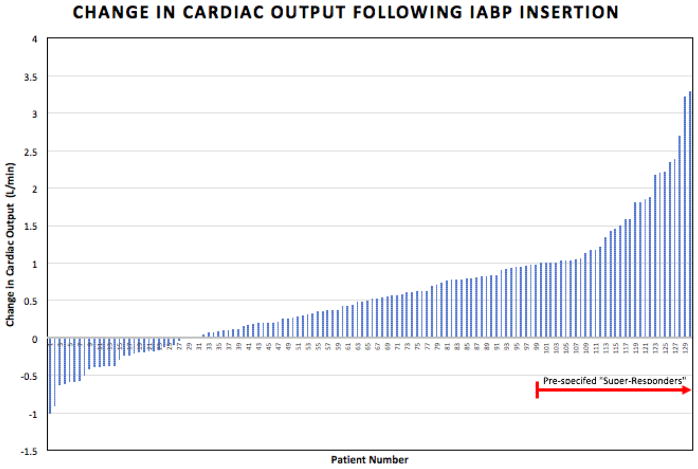

Hemodynamic super-response

The top quartile of hemodynamic improvement included patients whose CO increased by ≥ 0.98 L/min (Figure 4). When compared to the remainder of the study cohort, this subgroup of “IABP super–responders” also had greater reduction in mean PA pressures [−8 mmHg (IQR −17 – −2) vs. −4 mmHg (IQR −9 – 0), p=0.004] as well as CVP [−4 mmHg (IQR −6 – −1) vs −2 mmHg (IQR −4 – 1), p=0.01]. At baseline, super-responders had a right ventricular power index of 0.13 ± 0.05 W/m2 and a left ventricular power index of 0.24 ± 0.26 W/m2 while the remainder of the cohort had a right ventricular power index of 0.13 ± 0.03 W/m2 (p=0.91) and a left ventricular power index of 0.27 ± .06 W/m2 (p=0.01). In multivariable analysis including those univariable predictors meeting our criteria and both type of cardiomyopathy and heart rate as pre-specified variables, higher mean PA pressure was an independent predictor of robust hemodynamic response (OR 1.07; 95% CI 1.01–1.13; p=0.008; Table 3). Finally, “super–responders” had an increased likelihood of stabilization on IABP (87.9% vs 70.8%, p=0.049). If “super-response” was instead defined as the top quartile of reduction in mean PA pressures, corresponding to a reduction of 9 mmHg or greater, “super-responders” were more likely to experience clinical stabilization, though this difference was not statistically significant and not as pronounced as using the prior definition of hemodynamic “super-response” (clinical stabilization in 82.1% of “super-responders” vs. 71.0% of the remainder of the cohort; p=0.19).

Figure 4.

Change in Cardiac Output Following IABP Insertion. The top quartile of patients was pre-specified as “super-responders”. IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; L, liters; min, minute.

Table 3.

Analysis of Potential Predictors of Robust Hemodynamic Response to IABP Therapy. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. PA, pulmonary artery.

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Odds Ratio (95%CI) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Age | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 0.15 | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 0.07 |

| Male | 0.80 (0.28–2.28) | 0.68 | 1.40 (0.37–5.18) | 0.61 |

| Diabetes | 0.45 (0.18–1.14) | 0.09 | 0.44 (0.15–1.32) | 0.14 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 0.62 (0.26–1.50) | 0.30 | 0.34 (0.11–1.07) | 0.07 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 0.841 | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 0.99 (0.98–1.02) | 0.876 | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.42 |

| Central venous pressure (mmHg) | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 0.414 | ||

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | 0.03 | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | 0.008 |

| Multiple inotropes (≥2) | 1.12 (0.51–2.49) | 0.76 | ||

| Pressors (≥1) | 1.16 (0.49–2.75) | 0.74 | ||

| Baseline eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 | ||

| Mitral regurgitation (mod-sev) | 0.76 (0.33–1.74) | 0.518 | ||

IABP-Associated Complications

A total of 4 complications occurred in 3 patients during IABP support corresponding to a complication rate of 2.3%. Three patients required ≥ 2 units of PRBCs during IABP therapy though only 1 was related to access site bleeding. The same patient also had critical limb ischemia requiring device removal, and further evaluation diagnosed heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. The additional 2 bleeding events were not related to access site or directly linked to IABP therapy. No patient required endovascular or surgical intervention related to IABP, and no patient had a documented stroke while on IABP support. No pump malfunctions requiring catheter exchange occurred during the study period.

Discussion

This study represents the largest in-depth examination of IABP use in chronic systolic HF patients with acute decompensation and CS. We have described the clinical and hemodynamic response to IABP in this population and assessed the relative impact of pre-implant demographic, clinical, and hemodynamic parameters on clinical response. Our principal findings are: 1) IABP therapy in select chronic systolic HF patients with CS is associated with a high likelihood of bridge to HRT or discharge without the need of escalation to a more potent tMCSD, 2) poor right ventricular (RV) function, as measured by PAPi, and ICM are associated with clinical deterioration on IABP, and 3) hemodynamic response to IABP is variable in this population, but robust hemodynamic response is associated with clinical stabilization after implantation.

Despite significant advances in percutaneous interventions and device technology, CS continues to carry a short-term mortality rate as high as 30–50 percent though the findings of the CardShock study suggest that those without an acute ischemic etiology of CS have a better prognosis.11,12 Most studies have focused on patients who develop CS after AMI, and there is a paucity of data among chronic HF patients who develop CS following acute HF decompensation. While randomized data suggest that the IABP is neither beneficial nor harmful for patients with CS following AMI,7 our data demonstrate that the IABP may have utility in the treatment of patients with ADHF. Though our data are not randomized, the outcomes of our population are none-the-less encouraging. Despite a lower cardiac power index than patients in the SHOCK trial13, we found a 30-day survival of 84.1% with 78.0% of patients successfully bridged to HRT or discharged without need for escalation to another tMCSD. This finding is consistent with those of the CardShock study where patients without an ischemia-related etiology of CS had lower mortality rates than acute coronary syndrome patients despite similar clinical presentation and severity12. It is, however, important to note that unlike studies of circulatory support devices in the setting of AMI, the majority of “favorable” clinical outcomes in our study included bridge to HRT as opposed to ventricular “recovery”.

CS is not a single clinical entity but rather a condition that exists as a spectrum with varying phenotypes and degrees of severity. Importantly, our cohort of patients met hemodynamic criteria for CS, though they would not be considered severe refractory shock patients (i.e. INTERMACS profile 1). Tailoring medical and device-based therapies to the patient and clinical scenario is paramount to improving CS outcomes. The modest immediate hemodynamic response to IABP observed in our study was comparable to prior reports with this device.14 While the IABP may not be sufficient support for an AMI-CS patient previously healthy until a catastrophic ischemic insult, it may be sufficient to stabilize many chronic HF patients who have decompensated into CS but had previously adapted to a chronic low-output state. Furthermore, medical therapies aimed to do the same for those with CS pose additional threats to the patient (e.g. arrhythmia) not seen with IABP.

Though the response to IABP therapy may be more pronounced in chronic HF patients, it is important to note that the IABP relies on intrinsic pulsatility to achieve a desired response and is unlikely to be effective in the most severe CS cases, regardless of etiology. For patients with severe refractory shock (INTERMACS profile 1) other short-term tMCSDs like percutaneous LVADs or VA-ECMO are more appropriate as they are able to provide a greater degree of hemodynamic support (including biventricular support for some devices/configurations). These devices, however, carry a higher risk of adverse events and their use should be limited to clinical scenarios in which full or near full hemodynamic support is required15. Our findings are consistent with prior observations that the IABP carries a relatively low risk of such complications.7,16 Indeed, even long-term IABP use has been shown to have very low complication rates.17 Though the number of patients in this study requiring escalation to a more powerful device in attempts to stabilize them is limited, the outcomes of this subset appear inferior to those of the remainder of the cohort. Whether earlier implantation of such a device or bypassing IABP altogether might have improved these outcomes is unknown, but should be a focus of future research so that patient selection for this, and other devices can be optimized.

Our study identified several predictors of clinical deterioration on IABP, notably low PAPi and ICM. The importance of RV performance in predicting IABP response is consistent with results of recent retrospective studies examining IABP use in chronic HF patients.18,19 In a cohort of 54 patients bridged to LVAD using IABP, Sintek et al. observed that intrinsic contractile reserve, as defined by higher left and right ventricular cardiac power indices, was associated with clinical stabilization on IABP therapy. Similarly, in a retrospective analysis of 107 patients treated with IABP therapy for CS, Krishnamoorthy et al. found a higher incidence of unplanned tMCSD escalation in patients with biventricular failure when compared to isolated left ventricular failure (21% vs 2%; p<0.001).19

The observation that ICM was associated with clinical deterioration on IABP therapy is notable since the IABP is frequently used in patients with active myocardial ischemia. The tendency of ICM patients to have additional comorbidities like intrinsic renal disease and peripheral vascular disease may in part explain the increase in risk observed relative to their non-ischemic counterparts; however, additional studies are needed to validate and further explore this finding. Importantly, our findings challenge the notion that IABP is largely a therapy for ICM patients; instead IABP may be considered as first line device support for patients with ADHF in shock, particularly for those with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and higher PAPi.

We observed significant variability in the hemodynamic response to IABP insertion. While our results are consistent with studies demonstrating an average augmentation of CO by 0.5 L/min, it is notable that some patients had a more robust improvement in CO that was accompanied by a larger reduction in PA pressures. These patients may be considered “IABP super-responders”, akin to those considered “super-responders” to cardiac resynchronization therapy; it is therefore not surprising that they had improved clinical outcomes compared to the rest of our cohort. However, it is important to recognize that clinical stabilization and “super-response” were not perfectly aligned and lack of “super-response’ does not preclude clinical stabilization. Importantly, we found that defining “super-response” by augmentation of CO (as opposed to other favorable hemodynamic response to IABP) provided the greatest ability to differentiate between those with favorable versus unfavorable clinical outcomes. As with any therapy, a variable response to a hemodynamic support device should be expected. However, given the invasive nature of counter-pulsation, clinicians would ideally be able to predict which patients would derive the greatest benefit. Further study of this variability in hemodynamic response is an important next step in advancing the understanding of counter-pulsation in decompensated heart failure.

Identification of potential super-responders may be particularly important in the future, given several developments in this field. First, anticipated changes to heart transplant allocation guidelines in the U.S. that may prioritize IABP-supported patients will likely take effect shortly.20 In addition, a larger mega-IABP is now available, though how this device may affect hemodynamics when compared to smaller IABPs is not well characterized. A retrospective analysis of 150 patients who received this device demonstrated clinical efficacy with 72.7% of patients surviving to hospital discharge, though 34 required another tMCSD.21 Finally, the development of fully implantable counter-pulsation devices capable of supporting patients out of the hospital for longer periods of time offers exciting opportunities for patients with advanced HF and hemodynamic compromise while awaiting heart transplant.22

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations to note. The main limitation is its single-center, retrospective design. Though our sample size is among the largest in-depth examinations of IABP use in chronic HF patients, a smaller proportion of patients either required escalation to a more powerful device or were weaned off IABP and discharged without durable LVAD. Furthermore, the decision to escalate to another device was not strictly protocolized. The timing of pre- and post- implantation hemodynamics and laboratory measurements were not uniform nor were vasoactive medications held constant in all cases, limiting our ability to make conclusions regarding immediate hemodynamic response to IABP. Although all patients had CVP, PA pressures, and CO measured before and after IABP insertion, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was not measured in all instances, potentially preventing us from recognizing the power of this parameter to predict response to this therapy. As such, we also examined the clinical response of IABP therapy in these patients, although we recognize that clinical outcomes may be influenced by additional factors not measured in our study. Importantly, candidacy for advanced therapies was not a prerequisite for enrollment, as has been the case in similar studies of this patient population. Furthermore, all patients received an IABP and the lack of a control group introduces the possibility of selection bias. However, our study population was selected based on perceived clinical need and represents a “real world” population of chronic HF patients who underwent IABP placement for CS.

Conclusion

In selected chronic HF patients with decompensation into CS, IABP insertion is associated with a high likelihood of clinical stabilization and survival, particularly when used as a bridge to durable LVAD. Preserved RV function may predict a favorable response to this therapy. Hemodynamic response to IABP insertion was highly variable; some patients experienced a robust response to this therapy with augmentation of CO by 1 L/min or more and these “super-responders” had a higher likelihood of favorable clinical outcome. Further study is required to validate these findings and identify predictors of hemodynamic response.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Garan is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. KL2TR001874 and has received honoraria from Abiomed. Dr. Naka has received consulting fees from Abbott Vascular/St. Jude Medical. Dr. Karmpaliotis has received honoraria from Abbott Vascular and Boston Scientific. In addition, Dr. Kirtane reports institutional grant support from Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abiomed, CSI, Siemens, Philips, and ReCor Medical, Dr. Burkhoff reports institutional grant support from Abiomed, and Dr. Colombo reports institutional grant support from Abbott Vascular. None of the listed entities has had any involvement with the development of this manuscript. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Garan is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. KL2TR001874 and has received honoraria from Abiomed. Dr. Naka has received consulting fees from Abbott Vascular/St. Jude Medical. Dr. Karmpaliotis has received honoraria from Abbott Vascular and Boston Scientific. In addition, Dr. Kirtane reports institutional grant support from Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abiomed, CSI, Siemens, Philips, and ReCor Medical, Dr. Burkhoff reports institutional grant support from Abiomed, and Dr. Colombo reports institutional grant support from Abbott Vascular. None of the listed entities has had any involvement with the development of this manuscript. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roger VL. Epidemiology of Heart Failure. Circulation research. 2013 Aug 30;113(6):646–659. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Apr 21; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European journal of heart failure. 2016 Aug;18(8):891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European journal of heart failure. 2012 Aug;14(8):803–869. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werdan K, Gielen S, Ebelt H, Hochman JS. Mechanical circulatory support in cardiogenic shock. European heart journal. 2014 Jan;35(3):156–167. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stretch R, Sauer CM, Yuh DD, Bonde P. National trends in the utilization of short-term mechanical circulatory support: incidence, outcomes, and cost analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Oct 07;64(14):1407–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, et al. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012 Oct 4;367(14):1287–1296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morine KJ, Kiernan MS, Pham DT, Paruchuri V, Denofrio D, Kapur NK. Pulmonary Artery Pulsatility Index Is Associated With Right Ventricular Failure After Left Ventricular Assist Device Surgery. Journal of cardiac failure. 2016 Feb;22(2):110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang G, Ha R, Banerjee D. Pulmonary artery pulsatility index predicts right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation: the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2016 Jan;35(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korabathina R, Heffernan KS, Paruchuri V, et al. The pulmonary artery pulsatility index identifies severe right ventricular dysfunction in acute inferior myocardial infarction. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions: official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2012 Oct 01;80(4):593–600. doi: 10.1002/ccd.23309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Gore JM, Lessard D, Yarzebski J. Thirty-year trends (1975 to 2005) in the magnitude of, management of, and hospital death rates associated with cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Circulation. 2009 Mar 10;119(9):1211–1219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harjola VP, Lassus J, Sionis A, et al. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. European journal of heart failure. 2015 May;17(5):501–509. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fincke R, Hochman JS, Lowe AM, et al. Cardiac power is the strongest hemodynamic correlate of mortality in cardiogenic shock: a report from the SHOCK trial registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Jul 21;44(2):340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheidt S, Wilner G, Mueller H, et al. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in cardiogenic shock. Report of a co-operative clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1973 May 10;288(19):979–984. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197305102881901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Truby L, Mundy L, Kalesan B, et al. Contemporary Outcomes of Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Refractory Cardiogenic Shock at a Large Tertiary Care Center. ASAIO journal (American Society for Artificial Internal Organs: 1992) 2015 Jul-Aug;61(4):403–409. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson JJ, 3rd, Cohen M, Freedman RJ, Jr, et al. The current practice of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation: results from the Benchmark Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001 Nov 01;38(5):1456–1462. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koudoumas D, Malliaras K, Theodoropoulos S, Kaldara E, Kapelios C, Nanas J. Long-Term Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump Support as Bridge to Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation. Journal of cardiac surgery. 2016 Jul;31(7):467–471. doi: 10.1111/jocs.12759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sintek MA, Gdowski M, Lindman BR, et al. Intra-Aortic Balloon Counterpulsation in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure and Cardiogenic Shock: Clinical Response and Predictors of Stabilization. Journal of cardiac failure. 2015 Nov;21(11):868–876. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.06.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishnamoorthy A, DeVore AD, Sun JL, et al. The impact of a failing right heart in patients supported by intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation. European heart journal. Acute cardiovascular care. 2016 May 26; doi: 10.1177/2048872616652262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevenson LW, Kormos RL, Young JB, Kirklin JK, Hunt SA. Major advantages and critical challenge for the proposed United States heart allocation system. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation: the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2016 May;35(5):547–549. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visveswaran GK, Cohen M, Seliem A, et al. A single center tertiary care experience utilizing the large volume mega 50cc intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in contemporary clinical practice. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions: official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2017 Feb 01; doi: 10.1002/ccd.26908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeevanandam V, Onsager D, Song T, et al. The Hemodynamic Effects of Intravascular Ventricular Assist System (iVAS) in Advanced Heart Failure Patients Awaiting Heart Transplant. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 36(4):S194. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.