A structure–affinity relationship study led to the discovery of 7h–j as novel 5-HT4 receptor ligands showing Ki values in the subnanomolar range.

A structure–affinity relationship study led to the discovery of 7h–j as novel 5-HT4 receptor ligands showing Ki values in the subnanomolar range.

Abstract

Two small series of quinoline derivatives were designed starting from previously published quinoline derivatives 7a and b in order to obtain information about their interaction with the 5-HT4R binding site. Initially, the structure of 7a and b was modified by replacing their basic moiety with that of partial agonist 4 (ML10302) or with that of reference ligand 6 (RS-67-333). Then, the aromatic moieties of 4-quinolinecarboxylates 7a, d–f, and h–k or 4-quinolinecarboxamides 7b, c, and g were modified into those of 2-quinolinecarboxamides 9a–e. Very interestingly, this structure–affinity relationship study led to the discovery of 7h–j as novel 5-HT4R ligands showing Ki values in the subnanomolar range. The structures of all these compounds contain the N-butyl-4-piperidinylmethyl substituent, which appear to behave as an optimized basic moiety in the interaction of these 4-quinolinecarboxylates with the 5-HT4R binding site. However, this basic moiety was ineffective in providing 5-HT4R affinity in the corresponding 4-quinolinecarboxamide 7g, but it did in 2-quinolinecarboxamide ligands 9c–e. Thus, a subtle interrelationship of several structural parameters appeared to play a major role in the interaction of the ligands with the 5-HT4R binding site. They include the kind of basic moiety, the position of the carbonyl linking group with respect to the aromatic moiety and its orientation, which could be affected by the presence of the intramolecular H-bond as in compounds 9c–e.

1. Introduction

The neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) is recognized to play pivotal roles in several different physiological functions that are mediated by seven receptor subtypes.1,2 Among them, the vast majority belongs to the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) super family, with the exception of the 5-HT3 receptor, which is a ligand-gated ion channel.2 The 5-HT4 receptor (5-HT4R) has received a great deal of attention as a target for drug discovery and development, and some 5-HT4R agonists have entered the market as gastrointestinal drugs.3–5 Great efforts in the search of new drugs have produced a large number of 5-HT4R ligands (see for example compounds 1–6 in Fig. 1).5,6

Fig. 1. Structures of some representative serotonin 5-HT4R ligands.

Moreover, 5-HT4R agonists have been proposed to play a role in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (AD),7,8 potentially representing a new class of drugs for the treatment of the cognitive deficits associated with AD.7 For instance, the partial 5-HT4R agonist PRX-03140 (3) by Epix Pharmaceuticals was reported to improve cognitive processes by increasing the release of acetylcholine and soluble amyloid precursor protein (sAPPα).7

In the context of our interest in developing new serotonin receptor ligands,9–16 the aromatic moieties (AM) of standard 5-HT4R ligands 3 and 5 were replaced with the 2-methoxyquinoline system to obtain flexible compounds 7a and b (Fig. 2), which were in turn transformed into the corresponding conformationally constrained derivatives 8a–g in the aim of obtaining information on their interaction with the 5-HT4R.16

Fig. 2. Structure of previously published 5-HT4R ligands 7a and b and 8a–g.

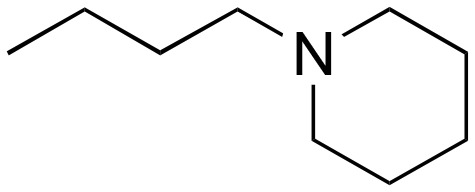

Very interestingly, ester 7a showed a 5-HT4R affinity in the nanomolar range along with antagonist properties, and the structure–activity relationship analysis in the conformationally constrained derivatives 8a–g suggested that the nature and the position of the substituents played a crucial role in determining the interaction with their receptor.16 Thus, the structure–affinity relationship studies in the class of quinoline derivatives 7a and b were deepened by replacing their basic moiety (BM-1 in Fig. 3) with BM-2, typical of partial agonist 4, or with BM-3 included in the structure of ligand 6.

Fig. 3. Design of quinoline ligands 7a–k and 9a–e (for the specific structures see Tables 1 and 2) from reference ligands 4, 5, and 6.

Moreover, the aromatic moiety of compounds 7a–k (i.e. AM-2) was structurally modified into the quinoline AM-3 of compounds 9a–e. The present paper reported on the synthesis and the structure–affinity relationship studies on quinoline 5-HT4R ligands 7c–k and 9a–e and the discovery of some novel ligands showing Ki values in the subnanomolar range.

2. Results and discussion

Target quinoline derivatives 7h–k were prepared starting from commercially available carboxylic acids 10a–d by activation with 1,1-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) and subsequent reaction with commercially available N-butyl-4-piperidinemethanol in the presence of DBU as the base (Method A, Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of target quinoline derivatives 7c–k. Reagents: (Method A, for 7h–k) BM-OH, CDI, DBU, DMF; (Method B, for 7g) BM-NH2, BOP, TEA, DMF; (Method C, for 7c) BM-NH2, EDC hydrochloride, DMAP, CH2Cl2; (i) BrCH3CH2Br, DBU, THF; (ii) suitable piperidine derivative, DIPEA, CH3CN (for 7d–f).

The synthesis of amide derivative 7g was accomplished from acid 10a by reaction with commercially available (1-butyl-4-piperidinyl)methanamine in the presence of BOP [(benzotriazol-1-yloxy)tris(dimethylamino)phosphonium hexafluorophosphate, Castro's reagent]17 as the coupling reagent (Method B). Acid 10a was used also in the preparation of amide 7c by using 1-(2-aminoethyl)piperidine as the amine and EDC hydrochloride as the activating agent (Method C). Acid 10a was finally alkylated with 1,2-dibromoethane in the presence of DBU as the base to afford bromoderivative 11, which was then reacted with the appropriate piperidine derivative to obtain the expected ester derivatives 7d–f.

Target 2-quinolinecarboxamide derivatives 9a–d were prepared according to the reaction sequence described in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of target 2-quinolinecarboxamide derivatives 9a–d. Reagents: (i) SOCl2, DMF; (ii) BM-NH2, (TEA), CH2Cl2; (iii) 1-Boc-4-(aminomethyl)piperidine, CH2Cl2; (iv) NaH, CH3OH; (v) HCl, C2H5OH; (vi) CH3CH2CH2CH2I, Na2CO3, C2H5OH.

Acid 12 (ref. 18) was activated with thionyl chloride and then reacted with the suitable piperidine derivatives to afford amide derivatives 7a–c and 13. The reaction of 13 with sodium methoxide in methanol gave methoxyderivative 14, which was deprotected with HCl in ethanol to give intermediate 15. Finally, ligand 7d was obtained by alkylation of 15 with n-butyl iodide in the presence of sodium carbonate as the base.

The synthesis of monovalent ligand 9e is described in Scheme 3.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of target 2-quinolinecarboxamide derivative 9e. Reagents: (i) (1-butylpiperidin-4-yl)methanamine, BOP, TEA, DMF.

Commercially available carboxylic acid 16 was converted into amide derivative 9e by reaction with (1-butyl-4-piperidinyl)methanamine in the presence of BOP, as the coupling agent. The structure of target compounds 9a and e was confirmed by crystallographic studies (Fig. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4. Structure of target compound 9a found by crystallography. Ellipsoids enclose 50% probability.

Fig. 5. Structure of target compound 9e monohydrate found by crystallography. Ellipsoids enclose 50% probability.

The binding affinity values of target quinoline derivatives 7c–k and 9a–e were measured as the activity in inhibiting the specific binding of [3H]GR113808 ([1-[2-(methylsulfonylamino)ethyl]-4-piperidinyl]methyl 1-methyl-1H-indole-3-carboxylate) to the 5-HT4R in guinea pig striatum membranes19 in comparison with reference ligands 1 and 4–6, and the results of the binding studies are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Affinity of quinoline ligands 7a–k for the 5-HT4R.

| ||||

| Compd | X | R | BM | K i (nM) ± SEM a |

| 7a b | O | OCH3 |

|

52 |

| 7b b | NH | OCH3 |

|

>1000 |

| 7c | NH | OCH3 |

|

>1000 |

| 7d | O | OCH3 |

|

15 ± 2.3 |

| 7e | O | OCH3 |

|

8.0 ± 1.5 |

| 7f | O | OCH3 |

|

304 ± 62 |

| 7g | NH | OCH3 |

|

>1000 |

| 7h | O | OCH3 |

|

0.62 ± 0.05 |

| 7i | O | Cl |

|

0.86 ± 0.15 |

| 7j | O |

|

|

0.44 ± 0.11 |

| 7k | O | H |

|

1.5 ± 0.27 |

aEach value is the mean ± SEM of 3 independent determinations performed in duplicate and represents the apparent affinity constant assessed in the [3H]GR113808 (final concentration 0.2 nM) specific binding assay to guinea pig striatum membranes.

bSee ref. 16.

Table 2. Affinity of 2-quinolinecarboxamide ligands 9a–e for the 5-HT4R.

| ||||

| Compd | R1 | R2 | BM | K i (nM) ± SEM a |

| 9a | Cl | H |

|

>1000 |

| 9b | Cl | H |

|

>1000 |

| 9c | Cl | H |

|

39 ± 5.5 |

| 9d | OCH3 | H |

|

148 ± 55 |

| 9e | H | OH |

|

76 ± 29 |

| 1 | 20 ± 5.5 | |||

| 4 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | |||

| 5 | 19 ± 3.5 | |||

| 6 | 3.9 ± 0.55 | |||

aEach value is the mean ± SEM of 3 independent determinations performed in duplicate and represents the apparent affinity constant assessed in the [3H]GR113808 (final concentration 0.2 nM) specific binding assay to guinea pig striatum membranes.

In agreement with the results obtained with the previously published quinoline derivatives 7a and b,16 amide 7c, was found to be virtually inactive, whereas the corresponding ester 7d showed an inhibition constant value in the nanomolar range. Thus, the replacement of BM-1 of ester 7a with BM-2 as in ester 7d produced a negligible effect on the binding affinity, which could be further modulated by the presence of the substituents in position 4 of the piperidine moiety as in ester derivatives 7e and f. In particular, the introduction of a –CH2OH group (as in 7e) was well tolerated by the receptor binding site, whereas the presence of Boc-amino as in 7f produced a significant decrease in the affinity.

Also in the small subseries of quinoline derivatives 7g–k bearing BM-3 as the basic moiety, the amide member 7g was found to be virtually inactive, while the corresponding ester 7h showed an outstanding binding potency, thus BM-3 appeared to be the optimized basic moiety capable of maximizing the productive interaction of these quinoline ligands with the 5-HT4R binding site. Thus, the subnanomolar affinity shown by ester 7h led us to explore further the structure–affinity relationships by changing the substituent in position 2 of the quinoline nucleus. In particular, the replacement of the methoxy group of 7h with a chlorine atom as in compound 7i produced a negligible effect on the 5-HT4R binding affinity, but in the small subseries of ester derivatives 7h–k, the highest binding potency was shown by the cyclopropyl derivative 7j (Ki = 0.44 nM), while the unsubstituted derivative 7k showed an inhibition constant value in the nanomolar range (Ki = 1.5 nM).

The analysis of the binding data obtained with quinoline derivatives 9a–e (Table 2) showed not only interesting analogies but also some apparent discrepancies with the structure–affinity relationship trends discussed above. First, in agreement with the results obtained with amide derivatives 7b and c, the corresponding amide derivatives 9a and b were found to be virtually inactive. By contrast, BM-3 based amide 9c showed an inhibition constant value in the nanomolar range. This apparent discrepancy seemed to suggest that the stereoelectronic features of AM-3 caused differences in the interaction of this compound with the 5-HT4R binding site with respect to that of subnanomolar ligands 7h–j. In particular, X-ray diffraction data obtained with single crystals of compounds 9a and e suggested the presence of an intramolecular H-bond between the amide NH group and quinoline nitrogen. This interaction rigidified the structure of compounds 9a–e so that the amide carbonyl was coplanar with the aromatic moiety and the chlorine atom could play a significant role in the interaction with the receptor.

In fact, the replacement of the chlorine atom of 9c with a methoxy group as in compound 9d produced a significant decrease in the receptor affinity, confirming the importance of the chlorine atom. However, its replacement with a hydrogen atom and the simultaneous introduction of a hydroxy group in position 8 of the quinoline nucleus as in compound 9e was tolerated by the receptor, suggesting that closely related compounds may adopt different binding modalities in the interaction at the 5-HT4R.

3. Conclusions

The structure–affinity relationship studies in the class of previously published quinoline derivatives 7a and b were deepened by replacing their basic moiety with that of partial agonist 4 or with that of reference ligand 6. Furthermore, the aromatic moieties of 4-quinolinecarboxylates 7a, d–f, and h–k or 4-quinolinecarboxamides 7b, c, and g were modified into those of 2-quinolinecarboxamides 9a–e. Very interestingly, this study led to the discovery of some novel 5-HT4R ligands showing Ki values in the subnanomolar range. In fact, in the subseries of 4-quinolinecarboxylates 7d–f and h–k, cyclopropyl derivative 7j showed an inhibition constant of 0.44 nM that was slightly lower than that of the corresponding methoxyderivative 7h (Ki = 0.62 nM) or the one shown by chloroderivative 7i (Ki = 0.86 nM). All these compounds show the N-butyl-4-piperidinylmethyl BM-3 substituent in their structure. Therefore, BM-3 emerged as an optimized basic moiety for the interaction of these 4-quinolinecarboxylates with the 5-HT4R binding site. Curiously, BM-3 was ineffective in providing 5-HT4R affinity in the corresponding 4-quinolinecarboxamide 7g, but it did in 2-quinolinecarboxamide ligands 9c–e. Thus, the interaction with the 5-HT4R binding site appeared to be regulated by the subtle interrelationship of structural parameters such as the kind of basic moiety, the position of the carbonyl linking group with respect to the aromatic moiety and its orientation, which could be affected by the presence of the intramolecular H-bond as in compounds 9c–e.

Experimental procedures were in compliance with national and international laws and policies on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (Italian Legislative Decree 26/2014 that transposed the EU Directive 2010/63/EU; Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, U.S. National Research Council, 2011), approved by the Rottapharm Biotech Review Board, and authorized by the Italian Minister of Health.

Author contributions

Synthesis and preliminary characterization: F. C., M. P., G. G., C. M. F., A. R., G. G., and M. A.; crystallographic studies: G. G.; binding assays: L. M., C. S., M. L., and G. C.; design of experiments, analysis of results, supervision, and writing of the paper: A. C.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Francesco Berrettini (Università di Siena) for technical support in the crystallographic studies.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Experimental details for the synthesis and the characterization of target compounds and their intermediates. The experimental procedures used in the biological studies. CCDC 1841095 and 1841096. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: 10.1039/c8md00233a

References

- Hannon J., Hoyer D. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;195:198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols D. E., Nichols C. D. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:1614. doi: 10.1021/cr078224o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumuis A., Sebben M., Bockaert J. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1989;340:403. doi: 10.1007/BF00167041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockaert J., Claeysen S., Compan V., Dumuis A. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:922. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois M., Fischmeister R. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:319. doi: 10.1021/jm020099f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglen R. M., Bley K., Bonhaus D. W., Clark R. D., Hedge S. S., Johnson L. G., Leung E., Whiting R. L. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:119. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen F., Smith J. A., Chang R., Bourdet D. L., Tsuruda P. R., Obedencio G. P., Beattie D. T. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodney M. A., Johnson D. E., Sawant-Basak A., Coffman K. J., Drummond E. M., Hudson E. L., Fisher K. E., Noguchi H., Waizumi N., McDowell L. L., Papanikolaou A., Pettersen B. A., Schmidt A. W., Tseng E., Stutzman-Engwall K., Rubitski D. M., Vanase-Frawley M. A., Grimwood S. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:9240. doi: 10.1021/jm300953p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli A., Anzini M., Vomero S., Mennuni L., Makovec F., Hamon M., De Benedetti P. G., Menziani M. C. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002;2:599. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli A., Butini S., Brizzi A., Gemma S., Valenti S., Giuliani G., Anzini M., Mennuni L., Campiani G., Brizzi V., Vomero S. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010;10:504. doi: 10.2174/156802610791111560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeazzi S., Hermans T., Paolino M., Anzini M., Mennuni L., Giordani A., Caselli G., Makovec F., Meijer E. W., Vomero S., Cappelli A. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:182. doi: 10.1021/bm901055a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli A., Manini M., Paolino M., Gallelli A., Anzini M., Mennuni L., Del Cadia M., De Rienzo F., Menziani M. C., Vomero S. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:571. doi: 10.1021/ml2000388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli A., Manini M., Valenti S., Castriconi F., Giuliani G., Anzini M., Brogi S., Butini S., Gemma S., Campiani G., Giorgi G., Mennuni L., Lanza M., Giordani A., Caselli G., Letari O., Makovec F. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;63:85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolino M., Mennuni L., Giuliani G., Anzini M., Lanza M., Caselli G., Galimberti C., Menziani M. C., Donati A., Cappelli A. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:8582. doi: 10.1039/c4cc02502d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolino M., Komber H., Mennuni L., Caselli G., Appelhans D., Voit B., Cappelli A. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:3985. doi: 10.1021/bm501057d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castriconi F., Paolino M., Giuliani G., Anzini M., Campiani G., Mennuni L., Sabatini C., Lanza M., Caselli G., De Rienzo F., Menziani M. C., Sbraccia M., Molinari P., Costa T., Cappelli A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;82:36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahboobi S., Sellmer A., Hocher H., Garhammer C., Pongratz H., Maier T., Ciossek T., Beckers T. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:4405. doi: 10.1021/jm0703136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlet D., Fourmaintraux E., Depreux P., Lesieur D. Heterocycles. 2003;60:385. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman C. J., Kilpatrick G. J., Bunce K. T. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:618. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.