Abstract

Background: Excessive breast cancer screening with mammography or other modalities often burdens patients with false-positive results and costs. Yet, screening patients beyond the age at which they will benefit or at too frequent intervals persists. This review summarizes the factors associated with overuse of breast cancer screening.

Methods: We searched Medline and Embase from January 1998 to March 2017 for articles addressing the overuse of breast cancer screening and hand-searched the reference lists of included articles. Studies were included if they were written in English, pertained to a U.S. population, and identified a factor associated specifically with overuse of breast imaging. Paired reviewers independently screened abstracts, extracted data, and assessed quality.

Results: We included 15 studies: 3 cohort, 5 cross-sectional, 6 surveys, and 1 in-depth interview. White women (non-Hispanic) were less vulnerable than other racial groups to overuse in 3 of 5 studies. Physician specialty was consistently associated with screening overuse in three of three studies. Abundant access to primary care and a patient desire for screening were associated with breast cancer screening overuse. Lower self-confidence, lower risk taking tendencies, higher perception of conflict in expert recommendations, and a belief in screening effectiveness were clinician traits associated with overuse of screening in the surveys.

Conclusions: The literature supports that liberal access to care and clinicians' recommendations to screen, possibly influenced by conflicting guidelines, increase excessive breast cancer screening. Overuse might conceivably be reduced with more concordance across guidelines, physician education, patient involvement in decision-making, thoughtful insurance restrictions, and limitations on the supply of services; however, these will need careful testing regarding their impact.

Keywords: : breast cancer, overuse, screening

Introduction

Health outcomes in the United States (US) lag behind those of other developed nations, despite health expenditures that are exceptionally high and growing.1–5 The disparity between costs and outcomes of care suggests that healthcare services are overused in the US.6 As suggested by Emmanuel and Fuchs, this phenomenon is driven by a “perfect storm” of patient, provider, and institutional determinants.7

One type of overuse of healthcare services is the practice of screening for cancers in populations that are unlikely to benefit from the screening. Cancer screening, particularly breast, prostate, and colon cancer screening, has been the focus of 12 published recommendations from the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force.8 In addition, the lists of the Choosing Wisely campaign include at least 22 items related to cancer screening.9

While screening practices that are contrary to guideline recommendations are known to be highly prevalent, the determinants of this screening overuse are poorly understood.10 We suggest that an examination of the determinants that are unique to overuse of cancer screening must be understood to design interventions well-targeted to reduce potentially harmful screening. Therefore, we sought to systematically review the literature to identify determinants, or associations, which have been identified to be positively or negatively associated with the overuse of screening for breast cancer. Our assumption is that the factors associated with overuse of cancer screening are specific to the clinical scenario; therefore, we focus, in this study, only on breast cancer screening.

Methods

For this review, we consider overuse to be the provision of healthcare services where the likelihood of harm exceeds the likelihood of benefit.11 Thus, overuse of breast cancer screening is the use of imaging in a patient unlikely to benefit from that imaging event.

Data sources and searches

This protocol was registered in Prospero (#42015029482). We initially searched broadly for determinants of overuse of healthcare services for diagnostic or treatment purposes, as a literature scoping exercise. We searched MEDLINE® and Embase® from January 1998 through July 2016. We developed a search strategy by using medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and key words relevant to the overuse of healthcare services, including procedures and diagnostic tests. The first search included the following terms: “medical overuse” OR “health services misuse” OR health services overutilization OR “unnecessary procedures” OR medically unnecessary procedures OR Diagnostic Tests, Routine/utilization OR Defensive Medicine OR Practice Patterns OR Health Services Abuse OR Health Services Overuse OR medical overutilization OR inappropriate utilization. We then updated the search through March 1, 2017 with a specific search for articles addressing cancer screening. Our focused search included the following: Early Detection of Cancer OR Mass screening OR Breast Neoplasms OR Mammography OR Papanicolaou Test OR Uterine Cervical Neoplasms OR Vaginal Smears OR Colorectal Neoplasms OR Colonoscopy OR “Breast cancer screening” OR “colorectal cancer screening” OR “cervical cancer screening” OR prostate cancer screening OR endoscopic OR “Pap tests” OR prostate-specific antigen.

We limited our search start date to January 1998 given the substantial differences in the healthcare environment in the past decades. We hand-searched the reference lists of each included article as well as related systematic reviews for additional articles.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and articles and came to consensus about inclusion. We included original, English-language studies not exclusively describing care delivered outside the US. Included studies needed to describe the use of a test for detection of incident breast cancer, and explore the association between a hypothesized determinant and overuse of the test, as operationalized by the authors (Tables 1 and 2). We had no restrictions regarding study design, including both quantitative and qualitative studies, but excluded studies that exclusively used data collected before 1996. We excluded studies that focused only at screening in women aged 40–49 because of the inconsistent recommendations for this age group.

Table 1.

Definitions of Overuse in Included Studies

| Any self-breast exam24 |

| Screening in patients with limited life expectancy16,18,22,24–27 |

| Guideline discordant screening |

| Offering nonrecommended MRI testing for screening17,19,20 |

| Utilizing multiple conflicting guidelines from USPSTF/ACS/ACOG22,25 |

| Screening more frequently than recommended16 |

| Patient's lack of awareness and knowledge, or negative attitude toward, or resistance to implement the revised USPSTF guidelines14,21,24 |

| Insufficient declines of screening mammography utilization among inappropriate population before and after 2009 USPSTF guidelines revision15,23,28 |

USPSTF, Preventive Services Task Force; ACS, American Cancer Society; ACOG American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Table 2.

Screening Guidelines Described in Included Studies

| Guidelines from USPSTF | Guidelines from ACS | Guidelines from ACOG | Unspecified | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al., 201214 | ♦ | |||

| Fedewa et al., 201615 | ♦ | |||

| Haas et al., 201616 | ♦ | |||

| Haas, et al.201617 | ♦ | |||

| Heflin, et al.200618 | ♦ | |||

| Kadivar, et al. 201419 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Kadivar, et al. 201220 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Kiviniemi and Hay 201221 | ♦ | |||

| Leach, et al. 201222 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Lee, et al. 201723 | ♦ | |||

| Record et al., 201624 | ♦ | |||

| Scheel et al., 201625 | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Schonberg, et al. 201326 | ♦ | |||

| Tan et al., 201427 | ♦ | |||

| Wharam et al., 201528 | ♦ |

♦ = guideline described in the study.

Data extraction, quality, and applicability assessment

Reviewers extracted information on the study and participant characteristics, the methods of data collection, the screening event, the determinants evaluated, and the determinants identified as being significantly (as defined in the article) associated with the overused screening event. The determinants were classified as being related to the patient, the clinician, or the environment, which includes the healthcare system. One reviewer did the data abstraction, and a second reviewer checked the abstraction for completeness and accuracy. Differences were resolved through discussion.

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of individual studies. The Critical Appraisal Checklist (Center for Evidence Based Management) was used for appraisal of the quality of included cohort studies and surveys12 and the Joanna Briggs Institute appraisal checklist for qualitative studies.13

Data synthesis and analysis

We created a set of detailed evidence tables. We qualitatively synthesized the results by the category of the determinants (patient, clinician, or environment) and created a summary table of these results. In the text, we highlight the most consistent results across studies.

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in this project.

Results

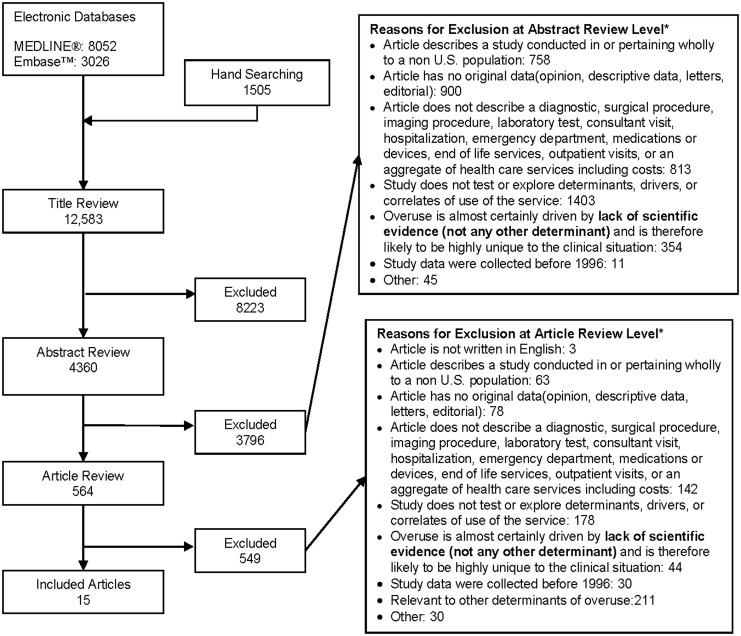

We identified 12,583 titles meeting our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). From these, we identified 564 articles for full-text review, of which 15 examined determinants of overuse of breast cancer screening (Table 3).14–28

FIG. 1.

Summary of the literature search.

Table 3.

Breast Cancer Screening and Significant Findings

| Author, year, Study design | Data source | Population experiencing an overuse event | Rate of observations of overuse events | Significantly associated with screening overuse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort studies | ||||

| Tan et al., 201427 N = 106,737 |

National 5% Medicare sample |

Women, aged 67–90, <7-year life expectancy | 28% of patients with <7-year life expectancy received mammography screening | Patient: having a PCP, having >1 generalist physician, having more visits to the generalist physician System and environment: higher PCP count per 100,000 residents, more mammographic facilities, higher count of radiologists per 100,000 residents |

| Wharam et al. 201528 Year 2005 (n = 2,124,892) Year 2009 (n = 2,229,582) Year 2012 (n = 2,006,150) |

National Administrative claims data from the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart data set, and 2000 U.S. census |

Women aged 40–64 years without mastectomy | Women aged 50–64 years had a 6.2% relative reduction (95% CI, _6.6% to _5.7%) in biennial mammography that was similar among white, Hispanic, and Asian women. Black women aged 50–64 years did not have changes in biennial mammography (0.4%; 95% CI, _2.6% to 3.5%). | Patient: white, Hispanic, and Asian had larger relative reduction in annual mammography rates compared to black |

| Haas et al., 201617 N = 311,332 |

The Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) | Women with <20% lifetime risk of breast cancer | 0.3% (777 of 311,332) of women with <20% lifetime risk of breast cancer received a screening MRI examination. Of the 1047 women who received a breast MRI, 74.3% were women with <20% lifetime risk of breast cancer. | Patient: more overuse among non-Hispanic race/ethnicity vs. non-white (non-Hispanic black or Hispanic or other); with college graduate or beyond, and followed by some college/technical school education, compared to most high school education. |

| Cross-sectional | ||||

| Schonberg et al., 201326 N = 2266 |

Women in the National Health Interview Surveys from 2008 to 2010 | Women aged 75 years and older | 56% of women older than 75 years reported a mammography within the past 2 years | Patient: younger ages, some college education or beyond, flu vaccine in past year, high mortality risk, history of benign breast biopsy Clinician: Clinician recommended mammogram |

| Fedewa, 201615 NHIS 2008–2013 (N = 18,459) |

National Health Interview Surveys on noninstitutionalized people from 2008 to 2013 | Women older than 40 years | Mammography prevalence decreased from 56.2% to 54.2% among older women (> = 75), from 2008 to 2013. Physician mammography recommendation declined in women aged older than 75 (−5.8% adjusted prevalence difference). |

Patient: Among women aged 50–64 years, those with non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity group, without any insurance, had more decrease in adjusted prevalence of mammography. Among women aged 65–74 years, those with less than high school education, with combination of Medicare and Medicaid, had less decrease in both adjusted prevalence of mammography and physician recommendation. Among women older than 75 years, those with college graduation, with non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity group, with Medicare, had more decrease in adjusted prevalence of physician recommendation |

| Scheel et al., 201625 N = 6,496 (Preventive medicine office visits to 1,962 physicians) |

National ambulatory medical care survey (NAMCS) | Women older than 40 years | Overall mammography referral rates decreased from 285 to 215 referrals per 1,000 visits between 2007–2008 and 2011–2012 (−25.0% adjusted change, p < 0.05). For > = 75 age group, mammography referral rates significantly decreased from 126 to 64 referrals per 1,000 visits between 2007–2008 and 2011–2012 (−51.1% adjusted change, p < 0.05). |

Clinician: greater decline in mammography referral rates among family physicians and internal medicine physicians than obstetricians and gynecologists; having a PCP. |

| Lee et al., 201723 N = 3442 |

Survey on women resided in Arkansas from 2007 to 2013 | Women aged 40–74 years with no breast cancer | 77% (2007–2010), and 68% (2011–2013) of white women aged 50–74 reported recent mammogram use. 76% (2007–2010), and 74% (2011–2013) of African-American women aged 50–74 reported recent mammogram use. | Patient: women who completed education by high school had a greater decline in mammography use than women who graduated from college; significant decline in mammography use among white women, but not observed among African-American women. |

| Haas et al., 201616 N = 209 (Providers) N = 30,233 (Patients) |

National Survey on women patients of participating PCPs affiliated with the clinical network of Brigham, Women's Faulkner Hospital, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health System or the University of Pennsylvania, and the PROSPR study |

Women aged 40–89 years | 44% of women aged older than 75 years received a screening, and 54% of those were annual. | Patient: younger women aged 40–74; with Hispanic race/ethnicity; having commercial insurance compared to public insurances. Clinician: Female gender; with a hospital network compared to community-based office/community health center/others; general internists, gynecologists, or mid-level providers were more likely to use screening than family physicians. |

| Survey | ||||

| Heflin et al., 200618 N = 2,003 |

National Survey of PCP's in AMA database |

Women aged 70–90 years | 33% of 2,003 physicians reported overscreening for breast cancer | Clinician: female gender |

| Allen et al., 201214 N = 150 patients |

Institution or health system survey on female patients within the Departments of Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, and Obstetrics & Gynecology at a tertiary care medical center |

Women aged 40–75 years | 75% of patients did not expect to change their timing or frequency of screening mammograms according to the revised guidelines. | Patient: women with a family history of breast cancer were more aware of the revised screening guidelines. |

| Kadivar et al., 201220 N = 743 (505 Breast cancer) |

National 2008 Women's Healthcare survey |

Clinical vignettes varying characteristics of either a 35- or 51-year-old and her race, insurance, family or personal history of cancer, and request for ovarian cancer screening | 75% of physicians reported offering some form of nonrecommended breast cancer screening | Clinician: USPSTF not considered most influential guideline, physician's belief in patient's risk |

| Leach et al., 201222 N = 1212 |

The National Survey of Primary Care Physicians' Recommendations and Practices for Breast, Cervical, Colorectal, and Lung Cancer Screening; questionnaire covering breast and cervical cancer screening | Women aged 50 years, 65 years, or 80 years with the terminal comorbidity, non-small cell lung cancer | 48% of PCPs reported overrecommending mammography. | Clinician: Obstetrics/gynecologists and followed by family medicine/general physicians overrecommend than internists; female gender; a racial/ethnic minority other than non-Hispanic white; working in a solo practice System and environmental: More overrecommendations in urban vs. rural areas; effect of ACOG guidelines on clinicians as “very influential”. |

| Kiviniemi and Hay 201221 N = 508 |

National commercial telephone survey on women older than 40 years | Women older than 40 years | NR | Patient: women aged 40–49 years; with higher income > = $35,000; with education above high school graduate were more aware of the changes in recommendations. |

| Kadivar et al., 201419 N = 553 |

National 2008 Women's Healthcare survey |

Clinical vignette of 51-year-old whose personal and family history did not put her at high risk for breast cancer | 33% of physicians reported offering nonrecommended breast cancer screening tests | Clinician: Low risk takers, belief in the clinical effectiveness of MRI as breast cancer screening test for average risk population |

| In-depth interview | ||||

| Record et al., 201624 N = 24 |

State Individuals in a seven-county Appalachian Kentucky region |

Women aged 18 years and older with negative breast cancer and mammography history | NA | Patient: women felt that having initial mammogram at 50 years was too late, false positives from screening also not of concern, guidelines were unknown to women, saw value in self-breast exams, and expressed preference that mammography should continue after the age of 75 |

AMA, American Medical Association; AAFP, American Academy of Family Physicians; ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; ACP, American College of Physicians; ADI, advanced diagnostic imaging; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CRC, colorectal cancer; DTC, direct to consumer advertising; FOBT, fecal occult blood testing; HMO, health maintenance organization; HPV, human papilloma virus; MSA, metropolitan statistical area, NR, not reported; PCP, primary care physicians; PET, positron emission tomography; USPSTF, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; VHA, veterans health administration; VA, veterans administration.

Characteristics of included studies

Among the included studies were three cohort studies,17,27,28 five cross-sectional studies,15,16,23,25,26 four surveys that measured physician's perceptions of the influence of guidelines on their practice or screening recommendations,18–20,22 two surveys that measured patients' knowledge or projected behavior changes in response to guideline changes,14,21 and one in-depth interview.24 From the 15 included studies, we identified 5 overlapping definitions of overuse, which were generally imaging that is discordant with guidelines (Table 1).

Risk of bias

The risk of bias was assessed as low in 10 of the 15 studies; 5 were determined to have a moderate risk of bias. Prominent flaws included the lack of reporting of response rates (in survey)18 and the lack of use of validated tools for data collection.19,21 One cross-sectional study25 used office-based preventive service visits from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) data, in which it was not possible to examine the frequency of screening by individual as some women patients could contribute multiple visits.

Factors contributing to overuse of breast cancer screening

Patient factors

All, but one22 of the included studies evaluated patient factors contributing to overuse of screening; ten of the 14 studies identified a significant association between some patient factor and overuse of screening.14–17,21,23,24,26–28

Two cross-sectional studies16,26 found that age significantly impacted receipt of overuse of screening mammograms. One used data from National Health Interview Surveys and reported that unnecessary mammography use was higher in women aged between 75 and 84 than those who were older than 84 years.26 In another study using cross-sectional data from 209 primary care providers and their 30,233 patients, 44% of women older than 75 years received a screening mammogram, and 54% of those were annual; however, mammography was more overused among younger women aged 40–74 years than those aged 75 years and older.16

Race and ethnicity were examined as factors of overuse in two cohort studies17,28 and three cross-sectional studies,15,16,23 and the directions of effects were inconsistent. One of the cohort studies28 and a cross-sectional study15 found that following the release of the 2009 USPSTF guidelines, mammography rates significantly decreased among white (non-Hispanic) women relative to black women. Consistent results were reported in another cross-sectional study of women in Arkansas; mammography use among white women declined significantly after the USPSTF guideline was revised, but no detectable change was observed among their African-American counterparts.23 However, one cohort study, using data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC), found that white (non-Hispanic) women at low risk of breast cancer (<20% lifetime risk) were 62% more likely than non-white women to receive a screening MRI, which the study investigators considered to be overuse.17

Higher social status was associated with overuse in five studies. One evaluated income,15 two investigated insurance,15,16 and four examined education.15,17,23,26 A cross-sectional study of older women found that unnecessary mammography was higher among women with at least some college education.26 In addition, compared to average-risk women with a high school education or less, the probability of receiving a screening MRI in excess of guidelines was 132% and 43% higher for those who had at least a college degree and those with some college or technical school education, respectively, relative to less education.17 However, another cross-sectional study reported that women with a high school education experienced a greater decline in mammography use after guideline changes than their counterparts with college degrees, comparing the 2007–2010 and 2011–2013 rates.23 Mammography overuse was positively associated with having at least some insurance, either private16 or public insurance.15

The self-reported data about screening intentions explored diverse potential contributors to overuse of screening. In the three surveys of physicians, neither race, age, screening history, and family history of cancer, nor requests for cancer screening changed women's decisions about receiving breast cancer screening.18–20 A national telephone survey of women found that women denied being disinclined toward screening mammography in response to changes in guidelines, with two-thirds of them describing the guideline changes as bad or very bad.21 In another survey of women at a tertiary care medical center, women with a family history of breast cancer reported greater awareness of the revised screening guidelines than women without a family history, but of the responding patients, three-fourths did not expect to change the age at initiation or frequency of screening mammography in the future.14 The majority of interviewed women in Appalachia responded that mammography should continue after the of age 75.24

Clinician factors

Eight studies, including three cross-sectional studies,16,25,26 one cohort study,27 and four surveys of physicians18–20,22 evaluated clinician factors contributing to overuse of breast cancer screening. Seven of them, including four surveys of physicians, found an association of clinician factors with overuse of screening.16,18–20,22,25,27

Clinician sex was infrequently studied, but one multivariate model adjusting for patient and provider characters found that female health providers were more likely to overuse mammography than their male counterparts.16 Physician specialty was evaluated as an influential contributor to overuse in three studies.16,25,27 A cross-sectional study using data from National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) found that, over time, family physicians and internists decreased use of mammography and obstetricians and gynecologists decreased use less so; these practices appeared to commensurate with their specialty societies' recommendations. Thus, judged according to the 2009 revised USPSTF guidelines, there was more overuse by obstetricians and gynecologists than by other clinicians.25 The finding that obstetrics/gynecologists overuse mammography more than family physicians was supported by another cross-sectional survey.16 The cohort study using Medicare data found that women having more contact with generalist physicians were more likely to be recipients of excessive mammography.27 In addition, a cross-sectional study found that mammography overuse in older women was influenced by a clinician recommending the test, although 37% of patients reported screening in the absence of a clinician's recommendation.16

Four surveys of physicians18,19,20,22 focused on their perceptions of their own screening overuse. In a survey of 2,003 primary care physicians identified through the American Medical Association (AMA), female primary care providers reported more mammography use consistent with overscreening than men, further supporting physician's sex as an influential factor.18 However, the other clinical vignette-based survey of physicians did not identify more intention to overuse mammography among female health providers than their male counterparts, nor among obstetrics/gynecologists when compared to family physicians.19

Physicians with lower risk-taking traits,19 those from a racial/ethnic minority,22 those working in a smaller practice (solo practice),22 and those who overestimated patients' cancer risks20 described a tendency to overuse breast cancer screening.

System or environmental factors

System or environmental factors were explored in nine studies: one cross-sectional study,25 three cohort studies,17,27,28 four surveys of physicians,18–20,22 and one survey of patients.21 Only two (one cohort study and one survey of physicians) found a positive association between any system factor and overuse of screening.22,27

With Medicare data supplemented with regional data, Tan et al. focused on supply of services as a driver of overuse, finding that lower patient volume, practice in a smaller city, a higher density of primary care physicians, a higher number of mammographic facilities, and a higher number of radiologists were associated with overuse of breast cancer screening.27

Three surveys of physicians18,20,22 and one survey of patients21 investigated geographic region as a factor of overuse. Only one physician survey found that overuse was modestly more prevalent in urban areas compared to rural areas.22 In the other survey, physicians responded that patient volume was not significantly associated with overuse.19

Discussion

We identified 15 studies evaluating patient, clinician or environmental factors associated with overuse of breast cancer screening. Half of the included studies either focused on patients' understanding of breast cancer screening guidelines,14,21,24 or care providers' beliefs and practices16,18,25; and the others evaluated the effects of USPSTF guideline changes in 2009 on breast cancer screening and screening overuse. As stated above, we are most interested in identifying associations with screening overuse that might prove to be causal and amenable to intervention.

To select points for intervention, it is often valuable to consider conceptual frameworks that illustrate the processes by which services are overused. There are fledgling frameworks that describe different aspects of overuse.29,30 Similarly, there is a framework that specifies the cognitive and behavioral antecedents that may lead to overuse of interventions by primary care providers.31 Indeed, many of the determinants that we identified in this systematic review fit well into these models; yet, we conclude that the evidence base remains too weak to support any of these as appropriate sites of intervention.

We found prominently, across studies, that physician specialty strongly predicted screening overuse, yet this is most likely driven by variability in the guidelines. Physicians who are unaware of guidelines, who have low confidence in guidelines, or who perceive conflict in the recommendations across guidelines are more likely to overuse screening than clinicians who are committed to practicing guideline-concordant care. We suspect that screening is the default option for clinicians who have limited time or skills to discuss harms and benefits of screening with each individual patient, especially with multiple conflicting guidelines.

This reviewed literature does not explicitly support that patients are requesting inappropriate screening, which had been our assumption. Yet, descriptive results in several surveys, and an in-depth interview, revealed that women are unconvinced about the disadvantages of guideline-discordant screening. They expressed anxiety about guideline changes and preferred not to change the frequency of their use of mammography.14 It cannot be assumed, however, that their screening use parallels their expressed preferences. Many included studies identified subgroups of patients that were at higher risk for screening overuse. We suspect that these may be the patients who are requesting screening: younger patients and patients with higher socioeconomic status such as with more education, higher income, or private insurance. Once a decision is made to screen, screening is facilitated by easy access to testing (as is common in metropolitan areas), abundant radiology facilities, and insurance that is permissive of testing.

Although the existing literature does not strongly identify where the ideal sites for intervention might be along the screening pathway, we suggest that there are points that might be modifiable with the goal of reducing overuse of cancer screening. Attention to the quality and evidence base of guidelines may increase physician confidence in guidelines. Efforts for consistency across guidelines from professional societies and other guideline-producing organizations may go a long way toward confident application of guideline recommendations. The U.S. Preventative Services Taskforce, established in 1984, makes evidence-based recommendations regarding effective preventative services,8 yet its recommendations are not always concordant with the recommendations from professional societies. For family medicine and internal medicine providers, their societies recommended individualized decisions on initiating regular screening for women under 50, biennial screening for women between 50 and 74, and no recommendation for or against screening mammography for women over 75 due to insufficient evidence of benefits, in line with the 2009 USPSTF guidelines.

The determinants, which appear to be driven by market forces, may be amenable to regulation. The Stark law addressed physician self-referrals for diagnostic testing, including imaging,32 perhaps there is a need to examine other financial incentives that influence referrals for cancer screening. Since the supply of facilities appears to be a driver of overuse, perhaps there should be required demonstration of regional need before new facilities are authorized, such as is done with Certification of Need state laws.33 These laws at present are applied only to hospital and nursing home beds, and hospice services. Certainly, there are many critics of these laws.

Efforts to restrict insurance coverage of screening seem more feasible; Medicare has restrictions on the frequencies of coverage of mammography, but could be even more restrictive if deemed appropriate and valuable. There is presently no upper age limit for coverage of cancer screening tests, as the more valuable metric is life expectancy, which is hard to know.

This systematic review has limitations. A major limitation is the varying definition of overuse across the studies, although this was expected. Some investigators assessed overuse as any mammography use among women with limited life expectancy, and some characterized overuse as patient report of past experiences with unnecessary screening. Self-reported data in the surveys may overestimate or underestimate documented receipt of screening test. Other authors assessed overuse by reductions in physician-reported screening use prerelease and postrelease of USPSTF guidelines. Findings may be highly contextual because of the heterogeneity across the study populations. Surveys with low response rates or unrepresentative population samples limit the ability to generalize conclusions. The quality of the included observational studies was high; our inclusion of surveys allowed us to review the more novel explorations of factors influencing overuse, such as guideline awareness and perceptions of risk.

Conclusion

This review exposes varied determinants of overuse in breast cancer screening, which have been described in the literature. Research is needed to test the impact of interventions targeting these demonstrated determinants or drivers of overuse of cancers screening. This will always need to be done with the utmost attention to not deny breast cancer screening services to women who are expected to benefit from screening.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the editorial assistance of Madeline Jackson.

We acknowledge the funding support from K24 AG049036-01A1 from National Institute on Aging (J.S., R.S); U1QHP28710 from Health Resource and Services Administration (S.N.); 2016 MSTAR Summer Scholar from American Federation for Research Training (J.P.); and Johns Hopkins University Dean's Fund (M.T.)

There has been no prior presentation of this work.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: Helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA 2012;307:1801–1802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodwin JS, Singh A, Reddy N, Riall TS, Kuo YF. Overuse of screening colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1335–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grady D, Redberg RF. Less is more: How less health care can result in better health. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:749–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ackerman S, Gonzales R. The context of antibiotic overuse. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:211–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Effect on Long-Term Federal Budget Outlook Largely Depends on Whether Cost Containment Sustained. GAO-13-281: Published: Jan 31, 2013. Publicly Released: Feb 26, 2013. Accessed February20, 2018

- 6.Reinhardt UE, Hussey PS, Anderson GF. U.S. health care spending in an international context. Health Aff (Project Hope) 2004;23:10–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emanuel EJ, Fuchs VR. The perfect storm of overutilization. JAMA 2008;299:2789–2791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. About the USPSTF. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/about-the-uspstf Accessed February20, 2018

- 9.American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. www.choosingwisely.org Accessed February20, 2018

- 10.Korenstein D, Falk R, Howell EA, Bishop T, Keyhani S. Overuse of health care services in the United States: An understudied problem. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Glossary: Underuse, overuse, misuse. Available at: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/glossary/u Accessed February20, 2018

- 12.Center for Evidence Based Medicine. Critical Appraisal of a Survey. https://www.cebma.org/wpcontent/uploads/Critical-Appraisal-Questions-for-a-Survey.pdf Accessed February20, 2018

- 13.Checklist for Qualitative Research—The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews

- 14.Allen SV, Solberg Nes L, Marnach ML, et al. Patient understanding of the revised USPSTF screening mammogram guidelines: Need for development of patient decision aids. BMC Women's Health 2012;12:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedewa SA, de Moor JS, Ward EM, et al. Mammography Use and Physician Recommendation After the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Breast Cancer Screening Recommendations. Am J Prev Med 2016;50:e123–e131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas JS, Barlow WE, Schapira MM, et al. Primary care providers' beliefs and recommendations and use of screening mammography by their patients. J Gener Intern Med 2017;32:449–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas JS, Hill DA, Wellman RD, et al. Disparities in the use of screening magnetic resonance imaging of the breast in community practice by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Cancer 2016;122:611–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heflin MT, Pollak KI, Kuchibhatla MN, Branch LG, Oddone EZ. The impact of health status on physicians' intentions to offer cancer screening to older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:844–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadivar H, Goff BA, Phillips WR, Andrilla CH, Berg AO, Baldwin LM. Guideline-inconsistent breast cancer screening for women over 50: A vignette-based survey. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:82–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadivar H, Goff BA, Phillips WR, Andrilla CH, Berg AO, Baldwin LM. Nonrecommended breast and colorectal cancer screening for young women: A vignette-based survey. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiviniemi MT, Hay JL. Awareness of the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force recommended changes in mammography screening guidelines, accuracy of awareness, sources of knowledge about recommendations, and attitudes about updated screening guidelines in women ages 40–49 and 50+. BMC Public Health 2012;12:899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leach CR, Klabunde CN, Alfano CM, Smith JL, Rowland JH. Physician over-recommendation of mammography for terminally ill women. Cancer 2012;118:27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JY, Malak SF, Klimberg VS, Henry-Tillman R, Kadlubar S. Change in Mammography use following the revised guidelines from the U.S. preventive services task force. Breast J 2017;23:164–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Record RA, Scott AM, Shaunfield S, Jones MG, Collins T, Cohen EL. Lay epistemology of breast cancer screening guidelines among appalachian women. Health Commun 2017;39:1112–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheel JR, Hippe DS, Chen LE, et al. Are Physicians influenced by their own specialty society's guidelines regarding mammography screening? an analysis of nationally representative data. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016;207:959–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schonberg MA, Breslau ES, McCarthy EP. Targeting of mammography screening according to life expectancy in women aged 75 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:388–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan A, Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Potential overuse of screening mammography and its association with access to primary care. Med Care 2014;52:490–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wharam JF, Landon B, Zhang F, Xu X, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D. Mammography rates 3 years after the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force Guidelines changes. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1067–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nassery N, Segal JB, Chang E, Bridges JF. Systematic overuse of healthcare services: A conceptual model. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2015;13:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipitz-Snyderman A, Bach PB. Overuse of health care services: When less is more … more or less. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1277–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powell AA, Bloomfield HE, Burgess DJ, Wilt TJ, Partin MR. A conceptual framework for understanding and reducing overuse by primary care providers. Med Care Res Rev 2013;70:451–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.STARK LAW. Available at: http://starklaw.org Copyright 2008–2013 Accessed December20, 2016

- 33.National Conference of State Legislatures. Available at: www.ncsl.org/research/health/con-certificate-of-need-state-laws.aspx Copyright 2016. Accessed December20, 2016