Abstract

Background: Female sex workers (FSWs) are at high risk for gender-based violence (GBV) and HIV infection. This study aimed to identify associations between GBV exposure in the past 12 months and biomarkers of physiologic stress and inflammation that may play a role in increased HIV risk among Kenyan FSWs.

Materials and Methods: Participating women responded to a detailed questionnaire on GBV and mental health. Plasma was collected for assessment of systemic C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels. Hair proximal to the scalp was collected to measure cortisol concentration. CRP and IL-6 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and hair cortisol concentration was determined by enzyme immunoassay. Log-transformed biomarker values were compared across GBV exposure categories using Kruskal–Wallis or Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Multivariable linear regression was used to explore associations between recent GBV and hair cortisol concentration.

Results: Two hundred eighty-three women enrolled, of whom 112 (39.6%) reported physical, sexual, or emotional violence in the past 12 months, 134 (47.3%) reported more remote exposure, and 37 (13.1%) reported no exposure. CRP and IL-6 levels did not differ across groups (p = 0.57 and p = 0.62, respectively). Among 141 women who provided hair, cortisol concentrations were higher among recently exposed women compared to the other two groups combined (p = 0.02). In multivariable regression, recently exposed women had higher hair cortisol levels than remotely exposed or unexposed women (adjusted beta = 0.52, 95% confidence interval 0.02–1.02, p = 0.04).

Conclusions: While CRP and IL-6 levels did not differ by GBV category, recent GBV was associated with increased hair cortisol concentration. GBV-related increases in cortisol could affect health outcomes and merit study in relation to HIV acquisition risk.

Keywords: : violence, abuse, sex work, inflammation, physiological stress, cortisol

Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV), including physical, sexual, or emotional violence, perpetrated by husbands, boyfriends, strangers, or acquaintances, is a common problem in sub-Saharan Africa. For example, in Kenya, 47% of women aged 15–49 report either physical or sexual violence in their lifetime.1 Structural factors such as patriarchy, gender inequality, and exclusion of women from political and financial life sustain the practice of GBV in this region.

Female sex workers (FSWs) are at heightened risk of GBV due to their greater vulnerability to gender power imbalances and to the stigma and criminalization of sex work.2 According to UNAIDS, 79% of FSWs in Mombasa, Kenya and 60% in Adama, Ethiopia reported work-related violence.3 According to the International Labor Office, FSWs are at high risk of violence perpetrated by clients, brothel owners, law enforcement agents, regular partners, family members, neighbors, and other sex workers.4 Long-term stress, depression, and low self-esteem are common outcomes among FSWs who have experienced violence of various forms.2

A growing body of evidence suggests a causal relationship between GBV and HIV acquisition. Recent prospective studies indicate that physical, sexual, and emotional GBV each result in increased HIV acquisition risk,5–7 with a dose–response effect for violence of increasing frequency and greater severity.5 GBV is thought to increase vulnerability to HIV infection through multiple behavioral, psychosocial, and biological pathways,8 including through physiological stress responses and inflammation, which may alter systemic immune responses after traumatic events.9 The physiological response to stress involves activation of the neuroendocrine system, of which the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is an important component. Recent data suggest that increased cortisol levels due to HPA axis activation may lead to glucocorticoid receptor resistance that could result in failure to downregulate inflammatory responses to viral and other triggers.10

With the overall goal of elucidating pathways to HIV vulnerability among GBV survivors, this study aimed to identify and characterize associations between GBV and biomarkers of stress and inflammation, including hair cortisol concentration and levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), among FSWs in Mombasa, Kenya. Our hypothesis was that physical, sexual, or emotional violence in the past 12 months would be associated with higher CRP, IL-6, and hair cortisol levels, relative to more remote exposure (>12 months) or no reported exposure.

Materials and Methods

Study population and recruitment

Study participants were drawn from the ongoing Mombasa Cohort, which enrolls HIV-negative women who report sex in exchange for cash, goods, or services such as payment of housing or school fees.11,12 Women attending routine monthly visits were invited to participate in a cross-sectional study of GBV and its effects. Screening was deferred to a subsequent visit if women were feeling unwell. To be included, women were required to be: (1) HIV negative at the last Mombasa Cohort visit; (2) willing and able to provide informed consent; and (3) not currently menstruating, pregnant, or less than 6 weeks postpartum. Research staff presented study objectives and reviewed the informed consent document with each interested woman in a private counseling room. Women who consented underwent all procedures for the GBV study and for the Mombasa Cohort on the day that consent was provided.11,12

Clinical procedures

Women completed the standardized interview for cohort visits, which covers medical history, contraception use, menstrual status, and sexual risk behavior, including frequency of sex with and without condoms and number of sex partners in the past week. After this interview, hair was collected for evaluation of cortisol concentration, by cutting ∼100 hair strands from the posterior vertex, as close to the scalp as possible. Whole blood was then collected in three vacutainer EDTA tubes (30 mL total), according to established standard operating procedures.

After sample collection, participants were taken to a private counseling room where a study nurse or counselor administered a detailed paper-based questionnaire to assess physical, sexual, and emotional violence. We based our questionnaire on the WHO Violence Against Women Instrument,13 but modified this instrument to capture violence from a variety of partner types and to include behaviorally specific questions on sexual violence from the Sexual Experiences Survey, to increase disclosure.8,14 The questionnaire asked whether women had ever experienced each of 15 specific acts perpetrated by a sexual partner (yes or no). In addition, we asked whether “anyone other than a husband, boyfriend, or client ever forced you to have sex or perform a sexual act when you did not want to,” to capture sexual violence from persons women did not consider to be sex partners. For each act reported, women were asked “When was the last time this happened?” and an estimated date was recorded. This questionnaire also included detailed information on the past five sexual partners, as well as screening questions for depressive symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) instrument,15,16 post-traumatic stress using the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian (PCL-C),17 alcohol use using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT),18 and other substance abuse using the Drug Abuse Screening Test 10 (DAST-10).19

Women who reported GBV, depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress symptoms, or ongoing substance abuse were offered ongoing counseling at the research clinic or referral to the Coast General Hospital's GBV Recovery Center, also in Mombasa.

Laboratory testing

Blood was held at room temperature until transport to the University of Washington/University of Nairobi Research Laboratory, ≈4 km from the research clinic, within 3–4 hours of collection. Upon receipt, samples were processed immediately for separation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and plasma aliquots for biomarker testing were transferred to −80°C freezers for storage. HIV testing was conducted by ELISA (PT-HIV 1,2–96, Pishtaz Teb Diagnostics, Tehran, Iran), confirmed by a second ELISA (Vironostika HIV-1 Uniform II AG/AB, bioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

Plasma IL-6 and CRP levels were measured using commercial ELISA Test Kits (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Camarillo, CA) performed in accordance with manufacturer's instructions. Concentrations were interpolated from four-parameter-fit standard curves using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Background levels were determined from blank wells included on each plate (assay buffer added instead of sample), and the subsequent optical density was subtracted from all samples and standards before analysis. Samples with optical densities below the lowest detectable standard (<2 pg/mL for IL-6 and <3.0 ng/mL for CRP) were assigned the value of that standard.

Hair was selected as the appropriate sample to measure cumulative (i.e., over months) physiological stress responses, as opposed to other samples, such as blood, urine, or saliva, which are subject to circadian variation.20 A method described by Meyer et al. was used to extract cortisol from hair at the University of Washington in Seattle, WA.20 The proximal 3 cm of hair was identified in each patient sample, and distal segments were discarded. Based on an average African hair growth rate of 0.79 cm per month,21 each hair sample was assumed to represent cumulative cortisol concentration over ∼3.8 months.

Before cortisol extraction, hair samples were washed in isopropanol thrice for 3 minutes each and dried thoroughly. A minimum of 15 mg of hair was weighed in a reinforced microcentrifuge tube and ground into a fine powder using a mini-BeadBeater (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK). Next, 1.5 mL of methanol was added to the tubes containing ground hair. The tubes were then rotated for 18–24 hours before centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes. One milliliter of methanol supernatant containing extracted cortisol was then removed from the pellet. A gentle stream of air was applied to evaporate the methanol to dryness. The extracted cortisol residue was reconstituted with 0.2 mL assay buffer (0.1 M PBS, pH 7.0 with 0.1 bovine serum albumin) and stored at −20°C for 1 week or less.

Hair cortisol concentrations were measured by a competitive microtiter plate enzyme immunoassay previously validated for use in serum specimens.22 This method has also been used successfully in salivary,23 urine,24 and dried blood spot specimens.25 A purified polyclonal anti-cortisol antibody, R4866 (provided by C. Munro at UC Davis), and cortisol reference calibrators (cat. no. Q3880, Steraloids) were used for this assay. The antibody binds 100% with cortisol, 10% with prednisolone, 6% with prednisone, 6% with compound S, 5% with cortisone, and less than 1% with other steroids, with a minimum detectable cortisol concentration of 302 pg/mL (personal communication, C. Munro). Two dilutions of a commercial quality-control sample (Bio-Rad Liquichek Immunoassay Plus, Level 2) were run on every plate. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation calculated using a variance components model for the 11 plates used in this study were 9.62% and 13.43%, respectively, for the high (6324 pg/mL) control and 11.69% and 11.71%, respectively, for the low (1106 pg/mL) control.

Data analysis

Women were initially classified into three exposure groups, based on the last reported exposure for any type of violence. “Recently exposed” women reported at least one act of physical, sexual, or emotional violence in the past 12 months, “remotely exposed” women reported at least one act of physical, sexual, or emotional violence more than 12 months ago, but no violence in the past 12 months, and “unexposed” women did not report any violence at any time (i.e., they responded “no” to all items). These three groups were compared using Pearson's chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables and the Kruskal–Wallis test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, as appropriate.

All three biomarkers were log-transformed for analysis. Hair cortisol, CRP, and IL-6 levels were compared across the three groups using scatter plots and the Kruskal–Wallis test by ranks. The proportion of women with IL-6 below the lower limit of detection was compared across groups using Fisher's exact test. To explore the relationship of hair cortisol levels with time since GBV exposure, data from exposed women were divided into three periods corresponding to <3.8 months (i.e., the period of growth for the hair sample collected), 3.8–12 months, and >12 months. For each of these periods, correlations between time since GBV exposure and hair cortisol concentration were evaluated using Spearman's rank correlation, and graphs were created with fitted prediction lines obtained by linear regression using Stata's lfitci command.

Finally, linear regression was performed to explore associations between GBV exposure category and hair cortisol concentration, adjusting for demographic, behavioral, and substance use characteristics that could potentially be associated with both GBV and hair cortisol concentration. Because there was no difference in hair cortisol concentration between women with remote exposure and women with no reported GBV exposure, these two groups were combined to increase power for comparison with the recently exposed women. Variables significant at p < 0.2 in bivariable analyses were carried forward into multivariable modeling. A final model, including symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress, was evaluated to determine the extent to which the impact of GBV on hair cortisol concentration could be mediated by these mental health conditions, which can also result from GBV.

Ethics

The study protocol and consent documents were approved by the Ethics Review Boards of Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi and the University of Washington. All participants provided written informed consent. Women were compensated 350 Kenyan shillings (≈$4.60 in the study period) for participating in the study.

Results

Two hundred eighty-three women enrolled in the study, with a median age of 33.5 years and median education level of 8 years. All participants tested HIV negative. GBV prevalence was high, with 246 women (86.9%) reporting lifetime physical, sexual, or emotional violence. Overall, 112 women (39.6%) reported physical, sexual, or emotional violence in the past 12 months; 134 (47.3%) reported more remote exposure; and 37 women (13.1%) reported no experience of GBV.

Table 1 presents characteristics of the study population overall and by GBV exposure category. The three groups differed significantly with respect to age and marital status; in that unexposed women were more often single and remotely exposed women were older and more often widowed or divorced. Significant differences were also found in terms of miraa (Catha edulis) use and scores on the PHQ-9, PCL-C, AUDIT, and DAST-10, with the recently exposed women reporting miraa use more frequently and having higher mental health symptom scores than the other two groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 283 Participating Women, Comparing Women Unexposed Versus Exposed to Physical, Sexual, or Emotional Violence in the Past 12 Months

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 283) n (%) or median (IQR) | Unexposed women (37) n (%) or median (IQR) | Women exposed remotely (134) n (%) or median (IQR) | Women exposed in past 12 months (112) n (%) or median (IQR) | p-Value for comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yearsa | 33.5 (27.2–40.6) | 32.1 (26.2–42.8) | 35.6 (29.8–43.4) | 31.0 (24.8–37.9) | 0.0001 |

| Education, years | 8 (7–12) | 11 (7–12) | 8 (7–12) | 8 (7–12) | 0.090 |

| Religion categorya | |||||

| Protestant | 139 (49.3) | 15 (41.7) | 71 (53.0) | 53 (47.3) | 0.710 |

| Catholic | 92 (32.6) | 12 (33.3) | 41 (30.6) | 39 (34.8) | |

| Muslim | 47 (16.7) | 8 (22.2) | 21 (15.7) | 18 (16.1) | |

| Other | 4 (1.4) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.8) | |

| Marital statusb | |||||

| Never married | 133 (47.3) | 23 (63.9) | 52 (38.8) | 58 (52.2) | 0.027 |

| Currently married | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Widowed/divorced | 146 (52.0) | 13 (36.1) | 81 (60.4) | 52 (46.8) | |

| Household size | |||||

| 1 person | 84 (29.7) | 12 (32.4) | 45 (33.6) | 27 (24.1) | 0.528 |

| 2–3 persons | 138 (48.8) | 16 (43.2) | 63 (47.0) | 59 (52.7) | |

| 4 or more persons | 61 (21.6) | 9 (24.3) | 26 (19.4) | 26 (23.2) | |

| Average weekly income | |||||

| ≤1000 KSh | 73 (25.8) | 7 (18.9) | 34 (25.4) | 32 (28.6) | 0.076 |

| 1001–2000 KSh | 76 (26.9) | 9 (24.3) | 46 (34.3) | 21 (18.8) | |

| 2001–5000 KSh | 87 (30.7) | 11 (29.7) | 36 (26.9) | 40 (35.7) | |

| >5000 KSh | 47 (16.6) | 10 (27.0) | 18 (13.4) | 19 (17.0) | |

| Workplacea | |||||

| Bar/restaurant | 133 (47.2) | 14 (38.9) | 69 (51.5) | 50 (44.6) | 0.479 |

| Nightclub | 115 (40.8) | 16 (44.4) | 52 (38.8) | 47 (42.0) | |

| Home | 8 (2.8) | 0 | 4 (3.0) | 4 (3.6) | |

| Other | 26 (9.2) | 6 (16.7) | 9 (6.7) | 11 (9.8) | |

| Charge for sexa | |||||

| Living expenses | 49 (17.4) | 7 (19.4) | 27 (20.2) | 15 (13.4) | 0.366 |

| ≤500 Ksh | 119 (42.2) | 11 (30.6) | 57 (42.5) | 51 (45.5) | |

| 500 KSh | 114 (40.4) | 18 (50.0) | 50 (37.3) | 46 (41.1) | |

| Age at first sexc | 17.0 (15.0–18.0) | 17.0 (16.0–18.0) | 17.0 (15.0–18.0) | 17.0 (15.0–18.0) | 0.535 |

| Years of sex work | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–4.5) | 2.5 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 0.693 |

| Tobacco use | |||||

| No | 248 (87.6) | 33 (89.2) | 120 (89.6) | 95 (84.8) | 0.535 |

| Yes | 35 (12.4) | 4 (10.8) | 14 (10.4) | 17 (15.2) | |

| Miraa use | |||||

| No | 210 (74.2) | 30 (81.1) | 107 (79.8) | 73 (65.2) | 0.019 |

| Yes | 73 (25.8) | 7 (18.9) | 27 (20.2) | 39 (34.8) | |

| Marijuana use | |||||

| No | 263 (92.9) | 33 (89.2) | 128 (95.5) | 102 (91.1) | 0.215 |

| Yes | 20 (7.1) | 4 (10.8) | 6 (4.5) | 10 (8.9) | |

| PHQ-9 score | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 0.0 (0.0–3.0) | 2.5 (0.0–6.0) | 3.0 (0.0–6.0) | 0.007 |

| PCL-C score | 17.0 (17.0–25.0) | 17.0 (17.0–20.0) | 17.0 (17.0–24.0) | 18.0 (17.0–26.5) | 0.038 |

| AUDIT score | 5.0 (0.0–10.0) | 5.0 (0.0–9.0) | 3.0 (0.0–8.0) | 6.0 (2.0–12.0) | 0.006 |

| DAST-10 score | 0.0 (0.0–0.0, range 0.0–8.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0, range 0.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0, range 0.0–7.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0, range 0.0–8.0) | 0.041 |

| CRP (ng/mL)a | 3797.1 (1598.0–5033.1) | 3199.8 (997.8–5527.5) | 4072.0 (1932.0–5346.1) | 3619.6 (1541.0–4645.8) | 0.569 |

| IL-6 detection | |||||

| Below limit | 230 (81.3) | 32 (86.5) | 106 (79.1) | 92 (82.1) | 0.614 |

| Above limit | 53 (18.7) | 5 (13.5) | 28 (20.9) | 20 (17.9) | |

| Hair cortisol (pg/mL)d | 13.8 (7.1–23.5) | 12.4 (7.2–17.8) | 13.4 (6.0–18.6) | 17.4 (7.7–41.2) | 0.056 |

1 missing value.

2 missing values.

3 missing values.

142 missing values.

AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAST, Drug Abuse Screening Test 10; IL-6, interleukin 6; IQR, interquartile range; KSh, Kenyan shilling (101 KSh ≈ $1.00); PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; PCL-C, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian.

Only 141 women (49.8%) consented to providing a hair sample for measurement of cortisol concentration. Of these 141 women, 48 women (34.6%) reported physical, sexual, or emotional violence in the past 12 months; 71 (50.4%) reported more remote exposure; and 22 women (15.6%) reported no experience of GBV. There was no association between GBV category and hair sample provision (χ2 = 4.08, p = 0.13). The most common reason for refusal, cited by 75.9% of women who refused hair collection, was technical difficulty due to braids or other hairstyles precluding easy sample collection. Women who provided hair samples were older (median age 35.3 vs. 31.0, p = 0.05), more likely to be widowed or divorced (60.7% vs. 43.3%, p = 0.002), had lower incomes (11.4% vs. 21.8% had an average weekly income >5000 KSh, p = 0.025), and had lower AUDIT scores (median 4 vs. 6, p = 0.007) than those who did not.

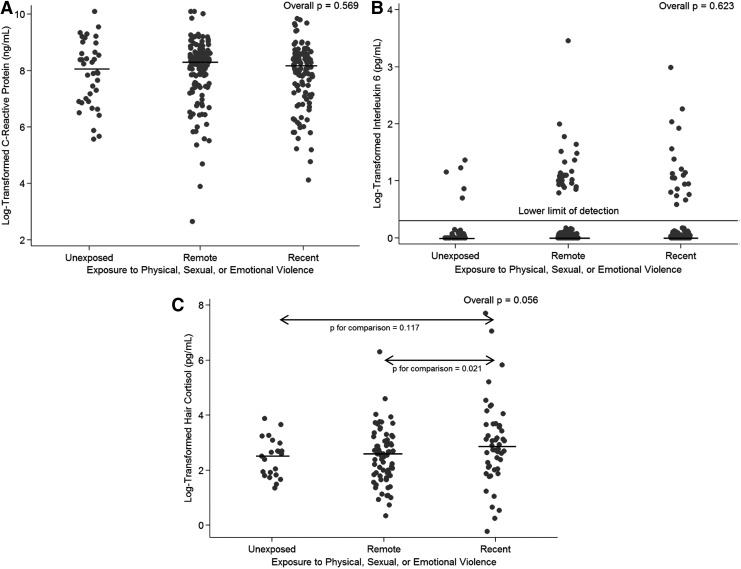

Overall, 81.3% of samples had no IL-6 detection. CRP and IL-6 levels did not differ across the three groups (Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.57 and p = 0.62, Fig. 1A, B, respectively), nor did detection of IL-6 (Fisher's exact p = 0.61). Among the 141 women who provided hair samples, hair cortisol concentrations did not differ significantly across all three groups (Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.06), but were significantly different when comparing women exposed in the past 12 months to those exposed more remotely (Wilcoxon rank sum p = 0.02, Fig. 1C) and when comparing women exposed in the past 12 months to the other two groups combined (Wilcoxon rank sum p = 0.02). There was no difference in hair cortisol concentration between women with remote exposure to GBV and those with no experience of GBV (Wilcoxon rank sum p = 0.78).

FIG. 1.

Log-transformed C-reactive protein (A), interleukin 6 (B), and hair cortisol concentration (C) by exposure group. Individual results are shown by each dot, and median values for each group (i.e., women exposed to GBV in the past 12 months, women exposed to GBV over 12 month ago, and women not reporting GBV exposure) are indicated with a black line. Kruskal–Wallis p-values are presented for across-group comparisons (i.e., overall p-values), and Wilcoxon rank-sum p-values are presented for pairwise comparisons. GBV, gender-based violence.

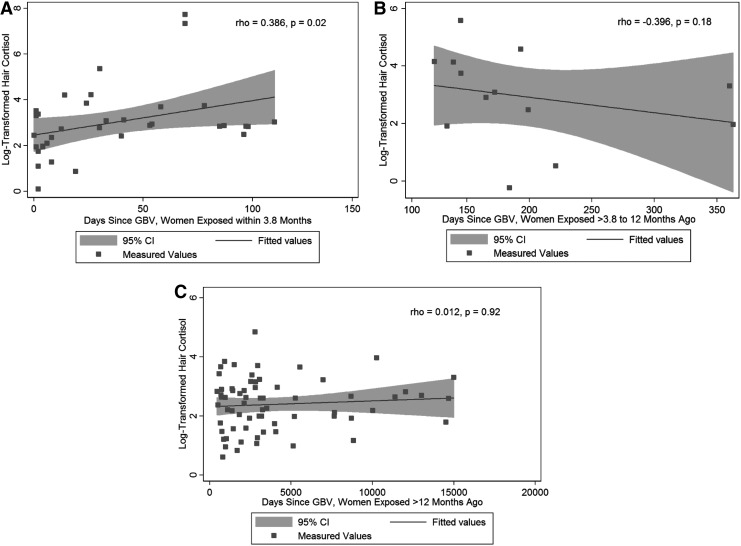

Among 35 women exposed to GBV within 3.8 months of the study visit (i.e., the period represented by hair samples in this study), there was a moderate positive correlation between hair cortisol concentration and the number of days since the most recent act of physical, sexual, or emotional violence (ρ = 0.386, p = 0.02, Fig. 2A). In contrast, there was no correlation between hair cortisol concentration and days since the most recent act of physical, sexual, or emotional violence among 13 women exposed to GBV >3.8–12 months before the study visit (ρ = −0.396, p = 0.18, Fig. 2B) or among 66 women exposed more remotely (ρ = 0.012, p = 0.92, Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Scatter plots of days since any physical, sexual, or emotional violence and log-transformed hair cortisol concentration. (A) Presents data for women exposed within 3.8 months of the study visit. (B) Presents data for women exposed more than 3.8 months but within 12 months of the study visit. (C) Presents data for women exposed more than 12 months before the study visit. Measured values, a fitted line, and 95% confidence intervals are presented for each panel, as are Spearman correlation coefficients and p-values.

Table 2 presents results of the regression analysis performed to explore factors associated with hair cortisol concentration. Because there was no difference in hair cortisol concentration between unexposed women and remotely exposed women, these two groups were merged to increase power. In bivariable analysis, recent GBV exposure, marital status, tobacco use, PHQ-9 score, and PCL-C score were associated with hair cortisol concentration at p < 0.20. In a multivariable model, including recent GBV exposure, marital status, and tobacco use (Model 1), GBV exposure in the past 12 months was associated with a 0.51 log higher cortisol concentration (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.02 to 1.00, p = 0.043), relative to cortisol concentrations in women without recent GBV exposure.

Table 2.

Linear Regression of Factors Associated with Log-Transformed Hair Cortisol Concentration

| Factor | Unadjusted betaa(95% CI) | p | Model 1,badjusted beta (95% CI) | p | Model 2,cadjusted beta (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBV exposure | ||||||

| None or remote | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Past 12 months | 0.52 (0.05 to 1.00) | 0.030 | 0.51 (0.02 to 1.00) | 0.043 | 0.52 (0.02 to 1.02) | 0.041 |

| Age, years | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.02) | 0.596 | ||||

| Education, years | −0.04 (−0.11 to 0.03) | 0.231 | ||||

| Religion category | ||||||

| Protestant | Reference | |||||

| Catholic | 0.34 (−0.17 to 0.85) | 0.194 | ||||

| Muslim | 0.05 (−0.43 to 0.53) | 0.837 | ||||

| Other | 0.25 (−0.25 to 0.75) | 0.328 | ||||

| Marital statusd | 0.089 | 0.724 | 0.940 | |||

| Never married | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Currently married | 0.14 (−0.18 to 0.46) | 0.15 (−0.36 to 0.66) | 0.08 (−0.42 to 0.58) | |||

| Widowed/divorced | −0.13 (−0.54 to 0.28) | −0.05 (−0.46 to 0.35) | 0.00 (−0.42 to 0.42) | |||

| Household size | 0.677 | |||||

| 1 person | Reference | |||||

| 2–3 persons | 0.10 (−0.35 to 0.56) | |||||

| 4 or more persons | −0.11 (−0.58 to 0.35) | |||||

| Income category | 0.619 | |||||

| ≤1000 KSh | Reference | |||||

| 1001–2000 KSh | −0.21 (−0.72 to 0.30) | |||||

| 2001–5000 KSh | −0.16 (−0.72 to 0.40) | |||||

| >5000 KSh | −0.35 (−0.87 to 0.17) | |||||

| Workplace | 0.282 | |||||

| Bar/restaurant | Reference | |||||

| Nightclub | −0.09 (−0.52 to 0.34) | |||||

| Home | 0.52 (−0.10 to 1.14) | |||||

| Other | 0.06 (−0.46 to 0.57) | |||||

| Charge for sex | 0.576 | |||||

| Living expenses | Reference | |||||

| ≤500 Ksh | 0.14 (−0.25 to 0.53) | |||||

| 500 KSh | 0.21 (−0.22 to 0.65) | |||||

| Age at first sexd | −0.04 (−0.14 to 0.07) | 0.465 | ||||

| Years of sex work | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.06) | 0.720 | ||||

| Tobacco use | 0.50 (−0.19 to 1.19) | 0.153 | 0.45 (−0.21 to 1.11) | 0.177 | 0.41 (−0.28 to 1.09) | 0.243 |

| Miraa use | 0.23 (−0.24 to 0.70) | 0.341 | ||||

| Marijuana use | −0.16 (−0.64 to 0.31) | 0.500 | ||||

| PHQ-9 Score | −0.03 (−0.07 to 0.01) | 0.139 | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) | 0.387 | ||

| PCL-C Score | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.00) | 0.149 | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | 0.433 | ||

| AUDIT Score | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | 0.650 | ||||

| DAST-10 Score | 0.04 (−0.11 to 0.19) | 0.591 | ||||

Unadjusted betas are the regression coefficients from bivariable modeling, with only the predictor and the outcome included.

Model 1 betas are the regression coefficient from multivariable modeling and therefore are adjusted for all predictors (GBV exposure, marital status, and tobacco use) included in the model.

Model 2 betas are the regression coefficient from multivariable modeling and therefore are adjusted for all predictors (GBV exposure, marital status, tobacco use, PHQ-9 score, and PCL-C score) included in the model.

One missing value.

CI, confidence interval; GBV, gender-based violence.

In a multivariable model, including these same factors, as well as PHQ-9 and PCL-C scores, which could potentially mediate the relationship between GBV and hair cortisol concentration (Model 2), recent GBV exposure remained associated with a 0.52 log higher cortisol concentration (95% CI 0.02–1.02, p = 0.041), relative to cortisol concentrations in women without recent GBV exposure. Neither PHQ-9 score nor PCL-C score was associated with hair cortisol concentration in this model, nor in separate models adjusting for only one of these two mental health scores.

In a sensitivity analysis excluding emotional violence as an exposure, results were similar. Ninety women (31.8%) reported physical or sexual violence in the past 12 months, while 128 (45.2%) reported more remote exposure and 65 (23.0%) reported no exposure. Recently exposed women had the highest depressive and post-traumatic stress symptom scores (Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.0036 and p = 0.0037 across groups, respectively), in addition to higher AUDIT and DAST-10 scores (Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.0002 and p = 0.018 across groups, respectively). While CRP and IL-6 levels did not differ across groups (Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.61 and p = 0.79, respectively), median hair cortisol concentration was highest in the recently exposed group (2.93 log pg/mL vs. 2.51 log pg/mL in remotely exposed women and 2.53 log pg/mL in unexposed women, Kruskal–Wallis p across groups = 0.016). Among 27 women exposed to physical or sexual violence within 3.8 months of the study visit, there was a moderate positive correlation between the number of days since the most recent act of physical or sexual violence and hair cortisol concentration (ρ = 0.415, p = 0.03).

In a multivariable regression analysis performed as for Model 1 above, with adjustment for marital status and tobacco use, recent exposure to physical or sexual violence was associated with a 0.57 log higher cortisol concentration (95% CI 0.03–1.11, p = 0.039), relative to cortisol concentrations in women without this exposure. In Model 2 with additional adjustment for PHQ-9 and PCL-C scores, recent exposure to physical or sexual violence was associated with a 0.60 log higher cortisol concentration (95% CI 0.04–1.16, p = 0.035), relative to cortisol concentrations in women without this exposure.

Discussion

This study examined biomarkers of physiological stress and inflammation in a cohort of Kenyan FSWs. Recent exposure to GBV was not correlated with CRP and IL-6, the biomarkers of inflammation studied. However, women recently exposed (i.e., in the past 12 months) to GBV exhibited elevated hair cortisol concentrations, reflecting an increase in physiological stress responses. Among women exposed to physical, sexual, or emotional violence within the time period corresponding to growth of the hair sample analyzed (i.e., 3.8 months), hair cortisol concentration was positively correlated with days since the most recent violent episode. After this time period, the association between days since last GBV episode and hair cortisol concentration diminished, suggesting that GBV causes an acute perturbation in HPA function, with consequent cortisol production and release that diminishes over time.

Although recent GBV was associated with higher scores on the scales used to assess depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and alcohol and other drug use, these scores were not associated with hair cortisol concentration. Moreover, the addition of PHQ-9 and PCL-C scores to multivariable modeling did not weaken the association between recent GBV and hair cortisol concentration, suggesting that poor mental health did not mediate the observed association between recent GBV and hair cortisol concentration.

Studies of the relationship between physical, sexual, and emotional violence and inflammation have had mixed results. Among healthy, postmenopausal U.S. women, Fernandez-Botran et al. found that a lifetime history of intimate partner violence was associated with elevated plasma CRP levels but not with elevated IL-6 levels.26 A study in a similar demographic found that higher CRP levels were associated with a history of being stalked, but this association was no longer significant after adjustment for body mass index.27 A history of physical assault among participants in this same study was negatively correlated with IL-6 production by phytohemagglutinin A-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells.27 Another U.S. study of adult women found higher plasma levels of CRP and IL-6 among women who reported sexual abuse in adolescence; however, this study found no such association among women who reported childhood sexual abuse nor in women who reported physical abuse in childhood or adolescence.28

These conflicting results do not lend credence to a strong association between GBV exposure and these biomarkers of inflammation, especially IL-6. In our study, in which the majority of women (87%) had experienced GBV at some point in their lives, there was no difference in CRP or IL-6 levels when comparing women exposed to GBV in the past 12 months to women who were unexposed or had more remote GBV exposure.

Recent models of HPA responsiveness, such as the Adaptive Calibration Model, posit that individual responses to threats, danger, or unpredictable or uncontrollable situations are modulated by adaptive developmental variation and regulated by feedback loops that have variable sensitivity depending on life history, resulting in large interindividual differences.29 Therefore, the relationship between recent, chronic, and lifetime traumatic events and physiological stress response is complex.

Several studies have suggested higher cortisol levels among individuals living in a traumatic environment. For example, among individuals in northern Uganda, an area of civil strife, Steudte et al. found that hair cortisol concentration was positively associated with the number of lifetime traumatic events experienced by participants.30 Likewise, hair cortisol concentrations were elevated among female adolescent survivors of the Wenchuan earthquake in China, then declined after the initial post-earthquake time period.31 Thus, our finding of a positive correlation between time since the most recent GBV episode and hair cortisol concentration in the short term (3.8 months in this study) is consistent with prior evidence.

The relationship between lifetime GBV and hair cortisol concentration seems to be more complicated. For example, Steudt et al. found that ever-traumatized participants who were living in a stable environment in Germany had lower hair cortisol levels than nontraumatized controls.32 In that study, in which 75% of participants had experienced the most upsetting traumatic event more than 5 years before study participation, hair cortisol concentration was inversely related to the number of lifetime traumatic events, frequency of traumatic events, and severity of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) intrusion symptoms.32 A longer time since traumatization has been associated with hypocortisolism in other studies as well.33,34 We found no association between hair cortisol concentration and post-traumatic stress symptoms in our study population, but did not ask detailed questions about the number and frequency of lifetime traumatic events. Moreover, GBV was extremely common in our study population, and the small number of women with no GBV exposure limited our power to detect differences between women remotely exposed to GBV and unexposed women.

Increased hair cortisol concentrations have been linked to obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, heart failure severity, and recent myocardial infarction.35 While no published studies have evaluated associations between hair cortisol concentration and HIV acquisition risk, cortisol is known to have important regulatory effects on inflammation and immunity.36–38 Indeed, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the relationship between diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes found the largest effect size for associations between flatter diurnal cortisol slopes (i.e., those in which cortisol decreased less over the day) and inflammatory or immune outcomes,39 including lower numbers of circulating natural killer (NK) cells and suppressed NK cell activity,40 decreased antigen response,41 higher toll-like receptor 4 inflammation (based on response of IL-6 and IL-1β to lipopolysaccharide stimulation),42 and increased CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation.43 While NK cells, inflammation, and target cell activation are all implicated in HIV-1 acquisition risk,44,45 further study of the relationship among GBV, elevated hair cortisol concentrations, and immune responses is required.

Ultimately, prospective studies of the biological effects of GBV among high-risk women with repeat sampling of relevant biomarkers and a rigorous evaluation of associations with HIV acquisition and other health outcomes are needed. FSWs are among the highest risk groups for GBV and HIV acquisition, making them a critical group for understanding how GBV may render women more biologically susceptible to infection with the virus. Increased attention is needed to address the high prevalence of GBV among FSWs, which impacts their mental health,46 sexual health,47 and even the health of their children.48

Evaluation of the impact of recent GBV on hair cortisol concentration in this study was limited by the low acceptance of hair collection, with only about half of the study population providing hair for testing. Most commonly, refusal was related to the traditional tress or braid hairstyle adopted by many Kenyan women, especially younger women. While most published studies of hair cortisol levels have required acceptance of hair sample collection as a condition of participation, we allowed refusal of hair collection, to reduce bias in the estimation of GBV prevalence in our study population.

Increasing acceptance of hair collection will be crucial to further characterize the impact of recent GBV exposure and other factors on hair cortisol concentration and other biomarkers on physiological stress. Acceptance of hair collection might be increased in future studies by the provision of hairdressing services on-site, to repair any damage caused by hair collection. Alternatively, fingernail sampling could be an effective and less invasive method for evaluating long-term stress responses, as fingernail cortisol levels have been moderately correlated with hair cortisol levels in at least one study.49

This study has several additional limitations. First, as with all cross-sectional studies, inference regarding cause and effect is not possible. While we did find slightly stronger associations when the GBV exposure variable was limited to physical and sexual violence, a potentially greater insult, and we detected a positive correlation between time since last violence and hair cortisol levels among women exposed during the period in which hair growth occurred, prospective studies are clearly needed. Second, study participants were asked to report GBV and mental health symptoms and may have been inclined to underreport. To mitigate social desirability bias, all interviews were conducted in a private counseling room, free of distraction. Third, most women had IL-6 levels below the level of detection of the assay used, which was not as sensitive as some assays on the market; therefore, it is possible we missed an association between GBV and IL-6. Finally, the women who participated in this study were participants in a long-standing FSW cohort and may not be representative of other FSWs in the study area or FSWs in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

Conclusions

GBV is an endemic problem in sub-Saharan Africa and affects FSWs disproportionately. Our findings indicate that recent GBV impacts physiological stress responses and is associated with increased hair cortisol concentrations, but not with systemic levels of CRP or IL-6. Although recent GBV was associated with mental health symptoms, the association between recent GBV and increased hair cortisol concentration was independent of and unaffected by adjustment for mental health symptom scores. Evidence suggests that elevated cortisol levels could be associated with increased HIV-1 acquisition risk, but additional study is needed. Future studies of hair cortisol concentration in GBV survivors should include incentives to providing hair samples and evaluate additional biomarkers to link HPA axis dysfunction to immune and inflammatory mediators of adverse health outcomes, including HIV-1 acquisition.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research staff for their contributions, the Mombasa Municipal Council for clinical space, and the Coast General Hospital for laboratory space. Special thanks go to their participants.

Funding

This research was funded in its entirety by a 2014 supplement grant from the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program under award number AI027757, which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers (the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases). Additional support for the Mombasa field site was provided by NIH grants R01 AI38518 and R01 HD072617. The views expressed in this publication are those of the researchers and not necessarily of the mentioned sponsoring institutions.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Kenya demographic and health survey 2014. Nairobi: Government of Kenya, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scorgie F, Chersich MF, Ntaganira I, Gerbase A, Lule F, Lo YR. Socio-demographic characteristics and behavioral risk factors of female sex workers in sub-saharan Africa: A systematic review. AIDS Behav 2012;16:920–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. The gap report. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz A, Klinger S. Gender-based violence in the world of work: Overview and selected bibliography/International Labour Office. Geneva: ILO, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kouyoumdjian FG, Calzavara LM, Bondy SJ, et al. Intimate partner violence is associated with incident HIV infection in women in Uganda. AIDS 2013;27:1331–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson N, Cockcroft A, Shea B. Gender-based violence and HIV: Relevance for HIV prevention in hyperendemic countries of southern Africa. AIDS 2008;22:S73–S86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study. Lancet 2010;376:41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Campbell JC. Forced sexual initiation, sexual intimate partner violence and HIV risk in women: A global review of the literature. AIDS Behav 2013;17:832–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalokhe AS, Ibegbu CC, Kaur SP, et al. Intimate partner violence is associated with increased CD4+ T-cell activation among HIV-negative high-risk women. Pathog Immun 2016;1:193–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Doyle WJ, et al. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:5995–5999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham SM, Raboud J, Jaoko W, Mandaliya K, McClelland RS, Bayoumi AM. Changes in sexual risk behavior in the Mombasa cohort: 1993–2007. PLoS One 2014;9:e113543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masese L, Baeten JM, Richardson BA, et al. Changes in the contribution of genital tract infections to HIV acquisition among Kenyan high-risk women from 1993 to 2012. AIDS 2015;29:1077–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet 2006;368:1260–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. J Consult Clin Psychol 1982;50:455–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monahan PO, Shacham E, Reece M, et al. Validity/reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 depression scales among adults living with HIV/AIDS in western Kenya. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:189–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther 1996;34:669–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption—II. Addiction 1993;88:791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav 1982;7:363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer J, Novak M, Hamel A, Rosenberg K. Extraction and analysis of cortisol from human and monkey hair. J Vis Exp 2014:e50882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loussouarn G. African hair growth parameters. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:294–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munro C, Stabenfeldt G. Development of a cortisol enzyme-immunoassay in plasma. Clin Chem 1985;31:956 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skinner ML, Shirtcliff EA, Haggerty KP, Coe CL, Catalano RF. Allostasis model facilitates understanding race differences in the diurnal cortisol rhythm. Dev Psychopathol 2011;23:1167–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trumble BC, Brindle E, Kupsik M, O'Connor KA. Responsiveness of the reproductive axis to a single missed evening meal in young adult males. Am J Hum Biol 2010;22:775–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konishi S, Brindle E, Guyton A, O'Connor KA. Salivary concentration of progesterone and cortisol significantly differs across individuals after correcting for blood hormone values. Am J Phys Anthropol 2012;149:231–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez-Botran R, Miller JJ, Burns VE, Newton TL. Correlations among inflammatory markers in plasma, saliva and oral mucosal transudate in post-menopausal women with past intimate partner violence. Brain Behav Immun 2011;25:314–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newton TL, Fernandez-Botran R, Miller JJ, Lorenz DJ, Burns VE, Fleming KN. Markers of inflammation in midlife women with intimate partner violence histories. J Womens Health 2011;20:1871–1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bertone-Johnson ER, Whitcomb BW, Missmer SA, Karlson EW, Rich-Edwards JW. Inflammation and early-life abuse in women. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:611–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Del Giudice M, Ellis BJ, Shirtcliff EA. The Adaptive Calibration Model of stress responsivity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011;35:1562–1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steudte S, Kolassa IT, Stalder T, Pfeiffer A, Kirschbaum C, Elbert T. Increased cortisol concentrations in hair of severely traumatized Ugandan individuals with PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011;36:1193–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo H, Hu X, Liu X, et al. Hair cortisol level as a biomarker for altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in female adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Biol Psychiatry 2012;72:65–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steudte S, Kirschbaum C, Gao W, et al. Hair cortisol as a biomarker of traumatization in healthy individuals and posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Biol Psychiatry 2013;74:639–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychol Bull 2007;133:25–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weems CF, Carrion VG. The association between PTSD symptoms and salivary cortisol in youth: The role of time since the trauma. J Trauma Stress 2007;20:903–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wester VL, van Rossum EF. Clinical applications of cortisol measurements in hair. Eur J Endocrinol 2015;173:M1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev 2000;21:55–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silverman MN, Sternberg EM. Glucocorticoid regulation of inflammation and its functional correlates: From HPA axis to glucocorticoid receptor dysfunction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1261:55–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webster JI, Tonelli L, Sternberg EM. Neuroendocrine regulation of immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2002;20:125–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adam EK, Quinn ME, Tavernier R, McQuillan MT, Dahlke KA, Gilbert KE. Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017;83:25–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:994–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sephton SE, Dhabhar FS, Keuroghlian AS, et al. Depression, cortisol, and suppressed cell-mediated immunity in metastatic breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun 2009;23:1148–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schrepf A, O'Donnell M, Luo Y, et al. Inflammation and inflammatory control in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: Associations with painful symptoms. Pain 2014;155:1755–1761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patterson S, Moran P, Epel E, et al. Cortisol patterns are associated with T cell activation in HIV. PLoS One 2013;8:e63429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Passmore JA, Jaspan HB, Masson L. Genital inflammation, immune activation and risk of sexual HIV acquisition. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016;11:156–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scully E, Alter G. NK Cells in HIV Disease. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2016;13:85–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rössler W, Koch U, Lauber C, et al. The mental health of female sex workers. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;122:143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee Opinion No 708: Improving awareness of and screening for health risks among sex workers. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e53–e56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willis B, Welch K, Onda S. Health of female sex workers and their children: A call for action. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e438–e439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Izawa S, Miki K, Tsuchiya M, et al. Cortisol level measurements in fingernails as a retrospective index of hormone production. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015;54:24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]