Multivalent cationic lipids such as gemini surfactants are an alternative to viruses for intracellular delivery of nucleic acids.

Multivalent cationic lipids such as gemini surfactants are an alternative to viruses for intracellular delivery of nucleic acids.

Abstract

Diseases that are linked to defective genes or mutations can in principle be cured by gene therapy, in which damaged or absent genes are either repaired or replaced by new DNA in the nucleus of the cell. Related to this, disorders associated with elevated protein expression levels can be treated by RNA interference via the delivery of siRNA to the cytoplasm of cells. Polynucleotides can be brought into cells by viruses, but this is not without risk for the patient. Alternatively, DNA and RNA can be delivered by transfection, i.e. by non-viral vector systems such as cationic surfactants, which are also referred to as cationic lipids. In this review, recent progress on cationic lipids as transfection vectors will be discussed, with special emphasis on geminis, surfactants with 2 head groups and 2 tails connected by a spacer.

1. Introduction

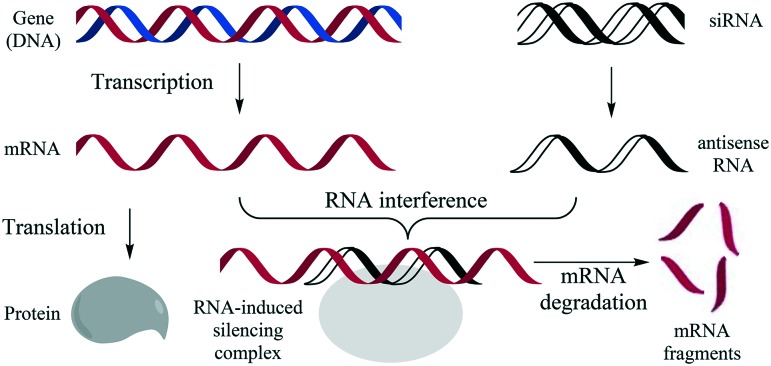

The technique of introducing nucleic acids into eukaryotic cells is called transduction when virus-mediated, and transfection when achieved by non-viral methods. Such techniques are not only important as research tools, but also find application in gene therapy. This has the potential to treat almost any hereditary disease because it aims to address a known defect: malfunctioning genes can be repaired directly by the delivery of functional DNA into the nucleus of a cell.1,2 Promising results have been obtained in recent gene therapy clinical trials in diverse areas like cancer3 and diseases of the blood,4 eye,5 and brain.6 Gene therapy can be implemented directly to cells in the body of the patient, or by way of stem cells that are removed from the patient and incorporated after transfection.7–9 Using the same or similar carriers10,11 cells can also be transfected by RNA instead of DNA, using in vitro transcribed mRNA to achieve protein expression.12–14 An even more powerful approach is the delivery of siRNA (small interfering RNA) as part of an RNAi (RNA interference) strategy,15–18 in which the delivery of a short double stranded RNA segment (20 to 25 base pairs) can silence the matching gene, as schematically represented in Fig. 1. The short RNA is complimentary to part of the mRNA of the gene and together they are bound in a RNA-induced silencing complex, in which the mRNA is degraded, thereby blocking its translation and shutting down the activity of the corresponding gene.19

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the RNAi (RNA interference) strategy.19 Left, the DNA of a gene is transcribed in the nucleus to mRNA (messenger RNA) and then translated into a protein in the ribosome; right, antisense RNA derived from siRNA (small interfering RNA) is bound to the RNA-induced silencing complex together with the complementary mRNA, leading to degradation of the latter.

Viral vectors are currently the most commonly used vectors in clinical trials, and viral gene therapy has been approved in China since 2003, and in Europe since 2013.1 Lentiviral (LV) vectors capable of integration of a therapeutic gene stably into the host genome were successfully developed.20 The 1st and 2nd generation LV vectors were incomplete retroviruses in which a therapeutic gene had been introduced, but they gave problems due to potential recombination with host viral sequences, replication, toxicity and immunogenicity.21,22 These problems are essentially solved in the 3rd generation LV vectors, which have led to many preclinical systems.23 Clinical application is however still hampered by safety concerns caused by random integration in the host genome, lack of efficiency of the available pseudotyped vectors, and the cost of clinical grade production of large batches of vector.24 The first viral systems developed for clinical use were adenoviral vectors, but they proved highly immunogenic and limited in topism and efficacy. Vectors derived from adeno-associated viruses are considered less immunogenic, can be produced in sufficient quantities, albeit at considerable cost, and have reached the stage of clinical trial and FDA approval.25,26

Because of the safety and cost problems of viral vectors there is an interest in non-viral vector systems. While such systems are hindered by (intra)cellular barriers and immune defence mechanisms against which viruses have evolved means to overcome, they can be made biocompatible and produced at low cost, and are easy to use.27 Non-viral delivery systems for DNA and RNA28 include cationic surfactants, also known as cationic lipids,29–33 but also cyclodextrins,34 and polymers such as polyethylenimine (PEI),35 dendrimers such as G2-octaamine,36 and materials related to carbon nanotubes.10,22 Non-viral carriers are now applied in a large number of clinical trials,37 with a share for cationic surfactants30,38,39 of 6%.2 Before addressing lipid carriers in detail, we will first discuss general properties of lipids and barriers in transfection.

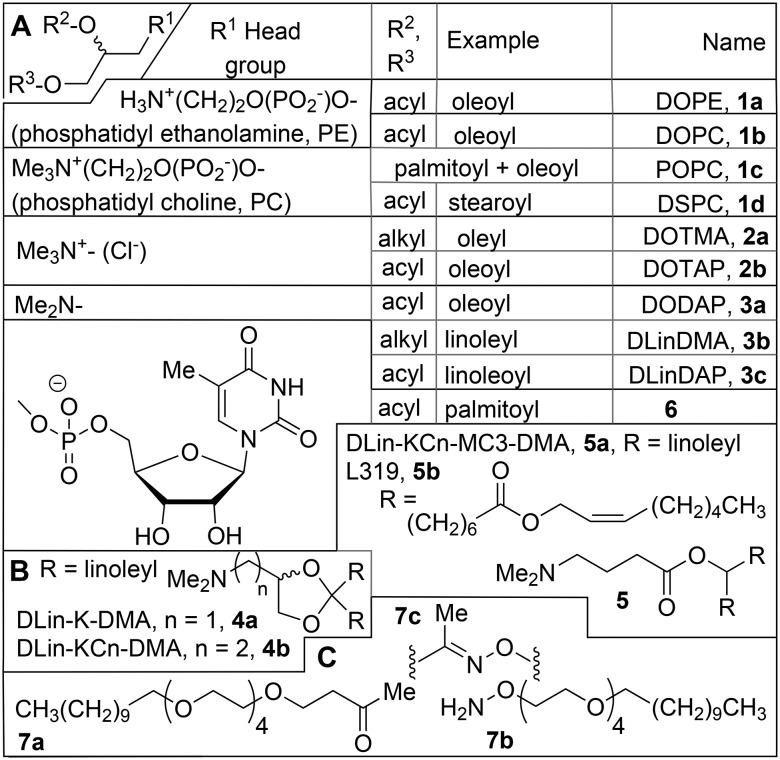

Amphiphiles (molecules with one or more polar, hydrophilic head groups and apolar, hydrophobic tails) are only sparingly soluble in water, and above a certain concentration, the critical aggregate concentration (CAC), they will form aggregates, in which the polar head groups are in contact with the solvent, whereas the tails will interact with each other, due to the hydrophobic effect.40 The packing parameter P relates the volume (V) of an amphiphilic molecule to its length (l) and head group area (a), via the equation P = V/a·l, and determines what kind of aggregate (P < 1/3, micelle; 1/3 < P < 1.2, cylindrical micelle; ½ < P < 1, vesicle; P = 1, bilayers, or P > 1, inverted micelle) will be formed.41,42 Glycerol is the most important linker between polar head groups and hydrophobic tails in biological lipids, such as the phospholipids.43 The phosphatidyl cholines (PC, Chart 1), the most important class of lipids (50%) in biological membranes, have a P value close to 1, and will therefore aggregate into a lamellar structure, such as a lipid bilayer. The phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE, Chart 1) head group is just a little bit smaller that than of PC, resulting in P > 1, so that inverted micelles are the preferred aggregate of this amphiphile in water. Because of this tendency, phosphatidyl ethanolamines are examples of lysogenic lipids, i.e. they disrupt bilayer structures, and find application as so-called helper lipids in transfection. Dispersion in water induces liquid-crystalline order in the bilayers; below the phase transition temperature Tc they are in a rigid state, above it in a fluid state. The introduction of tails with unsaturation, such as the oleoyl (C18:1) tails, also present in DOPE (see Chart 1), lowers Tc and increases the fluidity.

Chart 1. (Pseudo)glyceryl (A) and related lipids (B and C).

The DNA of eukaryotic cells, which has a length of the order of meters when fully stretched, is condensed to a size (μm range) compatible with that of the cell nucleus primarily by compaction in chromatin, which consists of nucleosomes.44 These are formed by the electrostatic interaction of the negatively charged DNA with the histone proteins,45 which are rich (30–40%) in the basic amino acids lysine and arginine. In specialized cells like the spermatozoa, the role of the histones is taken over by smaller proteins, the so-called protamines, which are rich in arginine, and by polyamines like spermidine and spermine (see section 2.2).

Transfection can be regarded as a special problem in drug delivery. Mechanistically, the introduction of new genes or siRNA through non-viral vectors is not straightforward; multiple barriers need to be overcome (Fig. 2).46–50 Delivery starts with complexation and condensation of the polynucleic acid by the cationic lipid aggregate into a so-called lipoplex (step 1),30,31 which then interacts with the cell plasma membrane by electrostatic attraction to proteoglycans on the cell surface (step 2); we will encounter various examples where the efficacy and cell selectivity are enhanced by incorporating receptor binding components in the lipoplex. The lipoplex enters the cell by endocytosis, via an endosome (step 3). The nucleic acids then risk being degraded, by lysosomal DNA-se, when the pH is lowered by the action of ATP-ases which convert the endosome to a lysosome (step 4); in order to avoid this they should leave the endosome (step 5), an escape promoted by (pH-dependent) lysogenic (helper) lipids. DNA then needs to travel through the cytoplasm and enter the nucleus (step 6) so that it can reach the appropriate transcription machinery, which leads to its expression as a protein (step 7) and the therapeutic effect (step 8). In viral transfection, the capsid proteins facilitate transport of large viral DNA molecules from the cytosol through the nucleopores into the nucleus.51 Non-viral transfection of non-dividing cells is problematic, because plasmid DNA cannot pass from the cytosol through the nuclear membrane.52 This is briefly absent only during mitosis, so that plasmid DNA can be taken up in the nucleus of the two daughter cells. All non-viral transfection systems rely on this, and this is the most important reason why the extrapolation of results obtained in vitro with rapidly dividing cell cultures to in vivo applications with few dividing cells is often disappointing. The release of siRNA from the lipoplex is easier, since the molecule is much smaller than a DNA expression cassette gene;53 furthermore it can perform its therapeutic action in the cytosol, and therefore the nuclear entry does not present an additional hurdle.

Fig. 2. Steps and barriers to overcome in gene delivery with non-viral vectors:31,50 1) complexation and condensation of the polynucleic acid by the cationic lipid into a lipoplex, 2) electrostatic attraction to the cell surface, 3) uptake by endocytosis, 4) degradation in a lysosome or 5) escape from the endosome, 6) entry into the nucleus, 7) expression as a protein, and 8) therapeutic effect.

It can be concluded that the following aspects are important: the carrier should i) compact the polynucleotide, reducing its size and sensitivity to mechanical and enzymatic attack, ii) allow effective uptake by endocytosis, iii) have a pH dependent lysogenic activity that allows escape form the endosomal compartment. Compaction of the DNA is promoted by multivalent cationic head groups. The emphasis in this overview will be on the development of multivalency, in which the so-called gemini surfactants, to be discussed in detail in section 3, play an important role. A complication in the comparison of the merits of the various transfection procedures are the variations in i) the standards used, ranging from the early lipid DOTMA 1, via Lipofectin™, Transfectam™, Lipofectamine™, and Lipofectamine 2000™,54 to Lipofectamin PLUS 2000™, ii) the use and choice of helper lipids, iii) the gene incorporated (often luciferase and/or β-galactosidase), or to be silenced, iv) the targeted cells (overview in ESI,† Table S1), and v) the cell viability measurements.

2. Lipid-based vectors

Lipid-mediated gene therapy was one of the earliest successful strategies used to introduce exogenous genetic material into host cells; it has received positive evaluations in clinical applications39 and favourable reviews in comparative studies of available reagents.37,55,56 Structure–activity relationships of early cationic lipopolyamines showed two trends. First, the density and nature of the cationic head group both affect the transfection; generally, a reduced charge density results in the formation of larger cationic complexes and lower toxicity.57 Second, for a given head group, the outcome of a change in the hydrophobic portion on transfection is difficult to predict;58 most successful cationic lipids as vectors for transfection, however, contain at least one unsaturation.59,60 Unfortunately, increasing the cationic character of the lipids also increased their toxicity, a feature already known for PEI.61 Neither head nor tail is the sole determinant of transfection efficiency; both domains have to be taken into consideration. Unfortunately, the combination of a ‘best head group’ and a ‘best alkyl tail’ will not automatically result in the cationic lipid with the best general transfection activity.

2.1. (Pseudo-)glyceryl lipids and terpenoids

Many lipid carriers for transfection take cationic analogues of phospholipids (1, Chart 1), the ‘pseudoglyceryl’ compounds622, in which the phosphate ester in the 1-position is replaced by a nitrogen-based cationic group, as a starting point, because of the expected compatibility with the plasma membrane. The positively charged head group has a dual function: it compensates the negative charge of the phosphate groups of the polynucleotides and plays a role in the association between lipoplexes and cells. The term ‘lipofection’ was coined63 to describe lipid-based gene transfection, viz. of COS-7 (African green monkey kidney fibroblast) and CV-1 cells with chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT), using 1,2-dioleyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTMA, 2a; Chart 1) in combination with the so-called helper lipid DOPE (1a) in a weight ratio α (= cationic lipid/{cationic lipid + helper lipid}) of 0.5, a combination commercialized as Lipofectin™; 2a was also the first lipid to be used for RNA transfection, viz. of NIH 3T3 cells with luciferase mRNA.64 Its observed toxicity was ascribed to the poor biodegradability of the lipid's ether bonds; replacement by ester bonds gave 1,2-di-(9Z-octadecenoyl)-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP, 2b),65 which is more easily degraded in vivo and therefore less toxic, although it is not necessarily always the better transfection agent. It is worth noting that contrary to their biological analogues, the pseudoglyceryl molecules are racemic, and neither enantioselective synthesis nor separation of the enantiomers to study their biological activities separately have been attempted; because the lipids are adjuvants, this is considered to be less important than if they would be themselves the therapeutically active molecules.

It is not necessary that a permanent charge, as in a quaternary ammonium group, is present in the molecule; lipids with a procationic (protonable) group such as in a tertiary amine are also applicable. The lipoplex of DODAP 3a (apparent pKa 5.8) with DNA could be formed at pH 4 and appeared in the cryo-electron microscope as multilamellar vesicles, probably with DNA between the lipid layers; it could be administered at physiological pH provided that a PEGylated lipid was added to prevent aggregation, and was eliminated from plasma significantly more slowly than free DNA or a lipoplex with a quaternary aminolipid.66 Of a number of cationic lipids that were combined with fusogenic and PEG-lipids as well as siRNA to give so-called stabilized nucleic acid lipid particles (SNALP), the polyunsaturated acyl analogue of DODAP, DLinDMA 3b, was found to be the most active in silencing Neuro2A (mouse) cells transfected with luciferase with siRNA.60 This was also the cationic component in the SNALP used to silence apolipoprotein B in non-human primates.67 The activity could be further improved by installing a ketal group in the linker (DLin-K-DMA, 4a), and even more by incorporating additional methylene groups between ketal and ionisable head group (DLin-K2-DMA, 4b), resulting in effective suppression of the murine clotting factor VII in mouse hepatocytes by siRNA in the order 4b > 4a > 3a > DLinDAP 3b.68 Even more active remote analogues are DLin-MC3-DMA 5a69,70 and its analogue L319 5b with a hydrolysable alkyl tail,71 which however are no longer (pseudo)glyceryl compounds (Chart 1B). Another interesting modification of phospholipids is that with nucleosides to give nucleolipids, which combine the molecular recognition principles seen in a DNA helix with the self-assembly characteristics of lipids, and feature hydrogen bonding and π-stacking forces as additional factors that promote lipoplex formation.72 Upon incorporation in DOPE liposomes (6/DOPE molar ratio 1/9) the anionic nucleolipid diC16-3′-T 6 (Chart 1) bound DNA at a Ca2+ concentration of 1 mM;73 the low Ca2+ concentration in the cell (1 μM) would therefore contribute to the release of DNA from the lipoplex. HEK293 cells could be transfected with pE-GFP (green fluorescent protein) at a relatively low toxicity. There appears to be no example of nucleosides attached to cholesterol or in a gemini, as discussed below for other head groups.72

The combination of anionic nucleolipids with Ca2+ is a way to evade the toxicity associated with cationic lipids. Another approach in which the use of cations is minimized, at least for cell-lipoplex recognition, is cell surface engineering using the SnapFect system.74 Here the cells to be transfected are immobilized and first exposed to mixed DOTAP (2b)/POPC (1c) liposomes containing the ketone-lipid 7a (Chart 1C), which fuse with the cell membrane to give the so-called ketone-cell, with ketone functionalities at the surface. These can then react with the lipoplexes, based on 2b/1c but also containing the oxyamine-lipid 7b, which reacts (clicks) with the ketone 7a to give the oxime 7c, promoting the interaction between target cell and lipoplex as well as subsequent transfection. The principle has been demonstrated for transfection of 3T3 fibroblast cells by GFP with high cell viability.

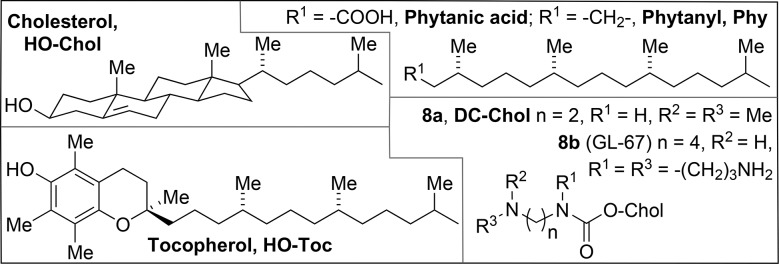

The steroid cholesterol (HO-Chol, shown in Chart 2 along with some other alternative hydrophobic tails) and its esters are the most important (30%) components of animal cell membranes, increasing the molecular packing by the hydrophobic interaction with the phospholipids' alkyl chains, while maintaining the membrane's fluidity and integrity. As expected on the basis of its compatibility with the cell membrane, it is possible to replace the two alkyl tails in a surfactant by a single Chol moiety, leading to vectors such as 3β-[N-(N′,N′-dimethylaminoethane)carbamoyl] cholesterol (DC-Chol, 8a, Chart 2); with DOPE as a helper lipid, the CAT plasmid was incorporated and expressed in a variety of cells of mammalian origin.75 Cationic derivatives of Chol proved, however, also to be protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitors,76 which is detrimental to the physiological integrity of a cell; derivatives with a quaternary nitrogen head group were much stronger inhibitors than tertiary ones.77

Chart 2. Alternative hydrophobic tails.

2.2. Multivalent cationic lipids

Most cationic lipids form polycationic aggregates (liposomes) of which the cationic groups can associate with the phosphate groups of the nucleic acids and thus neutralize their negative charges. In this reaction (eqn (1), step 1 in Fig. 2) the natural cationic counterions of the nucleic acid are exchanged for the cationic groups of the lipid aggregate.78 The lipoplex should preferentially be formed with an excess of positive charge, i.e. n for N+ (cationic lipid) > n in P–nn– (polynucleotide), so that it is attracted to the negatively charged cell surface (Fig. 2, step 2); this means that the nominal charge ratio, indicated as N/P (because the positive charge in the lipid is typically on N, and the negative charge in the nucleotide on P), has to be >1.

|

1 |

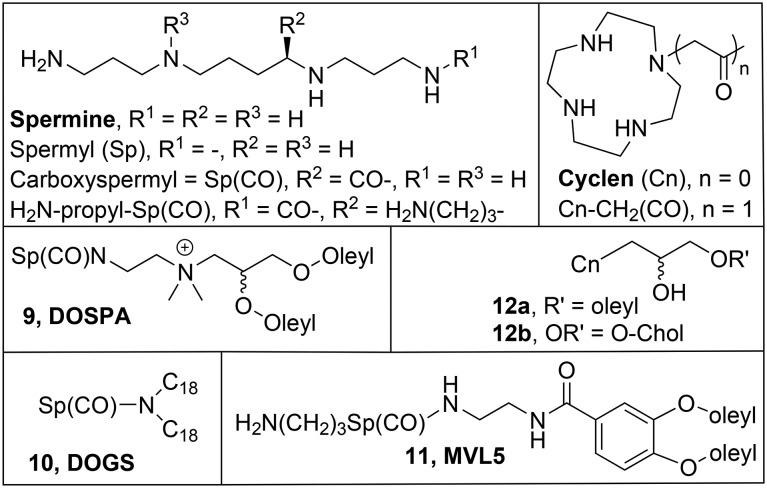

An important factor in the efficiency of the ion exchange reaction (eqn (1)) that leads to the lipoplex is the multivalency effect,79 by which multiple binding interactions can give rise to binding constants much higher than the sum of individual binding interactions. A single polynucleotide molecule has multiple negative charges, which can interact with multiple cationic charges on the surface of a liposome; to incorporate multiple cationic charges into a lipid molecule would therefore greatly enhance its DNA condensation ability. Examples of linear and cyclic multicationic groups are shown in Chart 3. For example, the combination of the pseudoglyceryl scaffold with carboxyspermine Sp(CO) gives 2,3-dioleyloxy-N-[2(spermine-carboxamido)ethyl]-N,N-dimethyl-1-propanamine (DOSPA, 9, Chart 3), an important component in the commercially available Lipofectamine.80 5-Carboxy-spermylglycine dioctadecylamide (DOGS, 10, Chart 3),81 which does not contain glycerol as a linker, is effective with saturated alkyl tails. The effect of (partial) replacement of the H atoms in the alkyl tails by fluorines has also been explored, as the resulting fluorocarbon tails are even more hydrophobic than their hydrocarbon analogues;82 indeed fluorinated analogues of 10,83,84 but also of DOTMA 2a85 and DOSPA 986 are also active in transfection, often with much reduced toxicity.

Chart 3. Multivalent cationic lipids.

The multivalent lipid 11 (MVL5, Chart 3) contains an additional propane-ammonium moiety in its head group, and has its hydrophobic tails attached to a 3,4-dioleyloxybenzoic acid scaffold; with DOPC 1b (Chart 1) as a helper lipid, it was more efficient in the transfection of mouse fibroblast L cells than DOTAP.87 It was also active in transfection of siRNA in knockdown of luciferase in mouse fibroblast L cells.88 Interestingly, like for DOTAP 2a, a larger amount of MVL5 11 is required for the transfection of siRNA than for DNA, due to the larger retention of counterions by plasmid DNA in the ion exchange reaction (eqn (1)). It should be mentioned here that cationic surfactants with long linear polyamine chains as head groups can have a low gene delivery efficiency because, as revealed by molecular dynamics simulations, they can undergo self-folding.89 For this reason, the cyclic polyamine cyclen has recently emerged as an alternative multivalent head group,90 and its pseudoglyceryl derivatives 1291 are shown here (Chart 3). As the mono-oleyl derivative 12a was less active and more toxic than the cholesterol analogue 12b, further examples of combinations of cyclens with other structural moieties will be discussed in the relevant sections.

2.3. Bola-amphiphiles

Another direction in the development of lipid-based vectors is the use of bipolar lipids, or bolaamphiphiles (bolas).92,93 Bolas carry two polar groups on opposite sides of the hydrophobic chain; they can span the biological membrane as a single molecule, and form monolayer membranes by themselves. Bolas with two different polar groups can be synthesized, for example with a neutral carbohydrate on one end, and a cationic Sp on the other, as in the early example GalSper 13a (Chart 4),94 and the more recent Orn-16-L 13b,95 which can generate asymmetric membranes (e.g. in the form of vesicles) having positively charged inner and neutral outer surfaces. In such cases the inner shell surface binds the DNA or RNA molecule, while the lack of positively charged groups on the outside minimizes the toxicity. The neutral outer membrane surface is utilized for exposure of biological signals for specific targeting. The galactose residue on the outer surface in 13 is expected to improve the transfection efficiency by recognition of the asialo-glycoprotein (ASGP) receptor in human HepG2 or murine BNL-CL2 hepatocytes and thereby promote receptor-mediated endocytosis. In spite of this advantage, the bolas alone showed relatively weak transfection efficiency. For 13b, efficiencies in the transfection of HeLa, COS-7 and HepG2 with luciferase that were comparable to PEI were only achieved at N/P 10 in the presence of DOPE (α = 0.5). In the bolas 14 with galactose and cationic head groups based on amino acids, fluorocarbon segments were inserted in the hydrophobic parts to varying extents.96 For the transfection activity of COS-7 cells with CAT, Lys was preferred to His, and the optimum degree of fluorination is important, since the Lys-containing 14a and, to a lower extent, 14b were active, whereas their His analogue 14c and the more highly and the less fluorinated analogues (structures not shown) were not.97

Chart 4. Bola-amphiphiles for transfection.

In another group of asymmetric bolas, the cell-penetrating peptide R8 (8 Arg residues) was combined with the tumor-targeting sequence RGD by means of a 12-amino-dodecanoic acid linker (15a, Chart 4),98 a 6-amino-hexanoic acid linker (15b), or no linker at all. They were compared to free R8 and PEI in the transfection of HeLa and 293T cells with luciferase. All peptides gave far better cell viability results (70–80%) for both cell types than PEI (11–12%). The transfection efficiency of 15 increased with the length of the spacer, and that of 15a was for a w/w ratio of 25 almost the same as that of PEI. In the series of symmetric bola 26 with dendritic peptide head groups based on lysine residues,99 the hydrophobic cores are relatively small, which is thought to be a disadvantage for insertion into the biological membrane. Of the various dendrons investigated (G1 with 1, G2 with 3, and G3 with 5 Lys) the G2 head group was found to be the best one; it is only mildly basic, since all amino groups of Lys are used in amide bond formation, and the dominant free amino acid residue is the imidazole group of the His component. The bolas 16 are about 2 orders of magnitude less toxic than their monomeric counterpart (the peptide dendron with just a lauroyl (C12) tail). Relatively large N/P ratios (up to 45) were needed to effect GFP gene silencing in NIH 3T3 cells, and the non-hydrophobic PEG analogue 16b was completely inactive. The fluorinated analogue 16c was remarkably effective in siRNA complexation, gene silencing, and serum stability. Compounds 16 also feature disulfide groups which are expected to be reductively split in the reducing environment of the cell (see section 2.4), effectively detaching the cationic dendrons from the hydrophobic core, by which the bola aggregate should be disassembled, leading to release of the nucleotide.

The conceptually simple bola 17 (Chart 4), with a single neutral hydroxyl group at one end and a trimethylammonium group on the other, did not form vesicles; combined with DOTAP (17/2b ratio 1 : 5), it was equally active in the transfection of HEK293 cells with GFP as 2b alone, but with reduced cytotoxicity.100 The symmetric multivalent bola 18 transfected HEK293, HepG2, NiH3T3, and HeLa, and 4T1 cells with luciferase (N/P 8, no helper lipid), with high cell viability (80–90%).101 Compound C6C22C619, a gemini (see section 3) with an extremely long spacer, had an activity comparable to that of Lipo2000* in transfection of COS-7 cells by GFP and luciferase with DOPE as the helper lipid (0.2 < α < 0.5).102

2.4. Bioreducible and/or dimerizable lipids

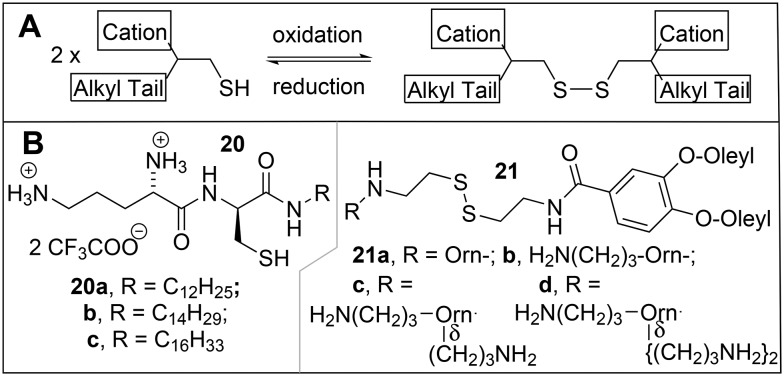

Amphiphilic molecules that contain thiol groups in the hydrophobic part can be oxidatively linked by disulfide formation to give a bola as in the example of 16 in the previous section; this bolaamphiphile can then be decomposed into the 2 monomers by splitting of the disulfide bond in the more reductive environment in the cell. This principle can also be applied to thiol groups in the polar head groups of amphiphilic molecules, where oxidation (Scheme 1A) would lead to a disulfide-containing gemini (see next section 3.1), which could be split into thiol-containing monomers in the cell. In this review, most dimerizable surfactants will be treated as bioreducible geminis in section 3 according to the type of head group and/or aliphatic tail involved; a few representative examples will be discussed here.

Scheme 1. A) Oxidative dimerization of an amphiphilic thiol into a disulfide gemini surfactant. B) Reducible transfection agents.

Investigations of a series of cationic Orn-Cys-alkylamine surfactants 20 (Scheme 1B)103 revealed that their oxidative dimerization was accelerated in the presence of DNA; the DNA molecule thus served as a template, binding the cationic molecules by ion-exchange, which then leads to the formation of gemini surfactants, according to the reactions given in eqn (1) and Scheme 1A, respectively. The activity in transfection of luciferase in 3T3 murine fibroblasts, BNL CL.2 murine hepatocytes, and HeLa cells increased in the order 20a < 20b < 20c, but was less than that of Transfectam™ by an order of magnitude. The activity of transfection of mouse fibroblast L-cells with luciferase by disulfide analogues of the multivalent cationic lipid MVL5 11, the CMVL series 21, were studied in mixed liposomes with DOPC.104 With 40% DOPC, the best compounds 21d and 21c had activities comparable to that of Lipofectamine 2000™, but with much better cell viability; the activity decreased with the number of positive charges in the head group in the order 21d > 21c > 21b > 21a.

3. Gemini surfactants

3.1. Introduction

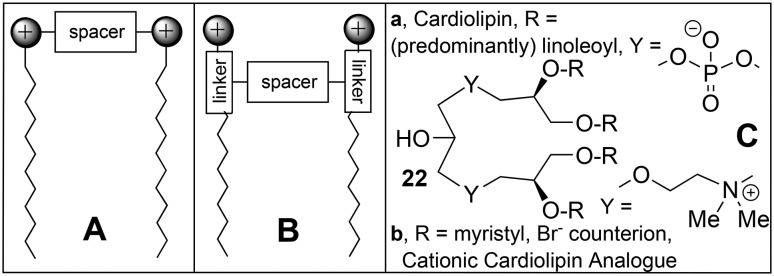

Gemini surfactants are a relatively young subfamily of amphiphilic molecules containing two head groups and two aliphatic tails which are linked by a spacer between the head groups, or between the linker region connecting the heads and the tails (Chart 5).105–108 Their critical aggregate concentration is 103-fold lower compared to the corresponding monovalent compounds (i.e. the classical surfactants with a single chain and a single head group), which reduces the amount of material required for e.g. solubilization and makes them interesting compounds for various applications,109 in particular biomedical ones,110–113 including transfection.50 The basic structure of geminis with their 2 head groups offers opportunities to take advantage of the multivalency effect (see section 2.2).

Chart 5. Gemini: A and B, general cationic gemini structure, connected at the head (A) or in the linker region (B); C, natural gemini (cardiolipin, 22a) and cationic cardiolipin analogue 22b.

If the area of the combined head groups is not larger than the cross section of the two tails (P ≈ 1), gemini surfactant molecules will aggregate into bilayers, and be compatible with the plasma membrane. An interesting difference in the behaviour of cationic surfactants in vesicle bilayers of anionic phospholipids is that all the anionic charge of the vesicle can be neutralized by addition of a classical cationic surfactant when the bilayer is in its ‘liquid’ state, and half of it when it is in the ‘solid’ state, whereas cationic gemini surfactants neutralize only half of the anionic charge, irrespective of the state of the bilayer.114 This difference is ascribed to the much lower propensity of gemini surfactants for ‘flip-flop’, which makes them much more similar to phospholipids than classical surfactants.111 Progress in the understanding of the physical chemistry of gemini and multivalent lipids in transfection has recently been reviewed,113 and will not be discussed in detail here.

The spacer in gemini surfactants opens great possibilities for variation, in addition to variations of the head groups and tails in conventional surfactants.107 It can be anything from a 2- to 10-carbon or longer aliphatic linker,93 or a rather polar polyamine.115 In some gemini surfactants the spacer is so dominantly aliphatic that they should practically be considered bola-amphiphiles (e.g. compound 19 in section 2.3).92,93 The head groups can vary from anionic sulfate via non-ionic sugars to cationic ammonium moieties, either chiral or achiral.116–118 Geminis that are asymmetric due to the presence of a peptide spacer have been dubbed geminoid or gemini-like surfactants119 and will be discussed in section 4. Interestingly, a biological gemini phospholipid is known, cardiolipin (22a, Chart 5C), which is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane and binds protons as well as cationic mitochondrial membrane proteins, such as the electron transfer protein cytochrome c.120 A cationic analogue of this natural lipid, 22b, with saturated alkyl tails connected through ether bonds,121 was proved to be effective in siRNA therapy against a number of tumors.122

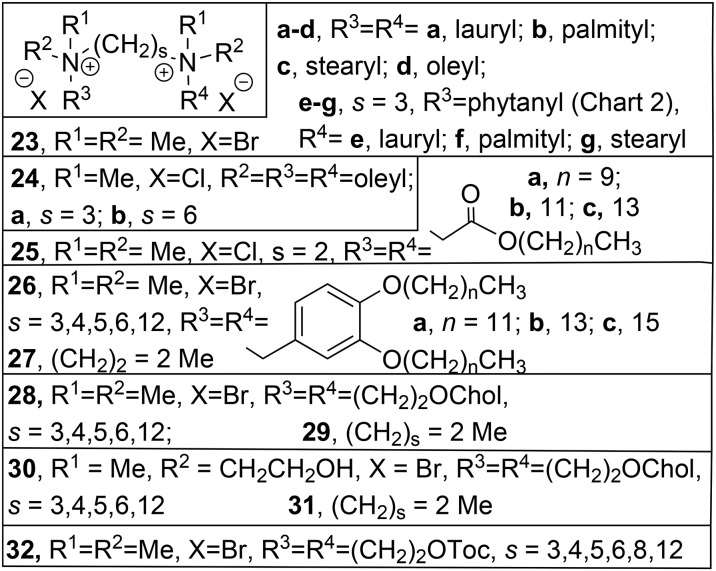

3.2. Quaternary ammonium geminis

The classical cationic gemini surfactant m-s-m106 has two quaternary ammonium head groups, linked by a spacer of s –CH2– groups, each containing a long alkyl tail with m carbon atoms. In an initial study, the transfection activities (BHK cells, pCMV-βgal) of the compounds with saturated C16 tails 23b (s = 2, 3, 6, Chart 6) did not differ much from those of the unsaturated analogues 23d, with an optimum value of 6 for s.123 No helper lipid was required but the transfection was negatively affected by the presence of serum. In spite of this apparent limitation, 23b with s = 3 (16-3-16) and its dodecyl analogue 23a (12-3-12) were successfully applied in the transfection with the gene for interferon γ in a therapy for the connective tissue disease, localized scleroderma.124 Dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide (DTAB) and its C14- and C16-analogues, which can be considered to be single chain analogues of the gemini 23, have been used with the helper lipid DOPE (1a) liposomes in the transfection of L929 (mouse fibroblast) cells with CAT, but turned out to be much more toxic than the Lipofectin™ standard.125 In a more recent study on transfection by 23b with s = 2, 3, 5, or 12 in the presence of 1a, the optimum spacer length was much lower (s = 2 or 3).126 These transfection studies were carried out in vitro with HEK293T, HeLa, CHO, U343, and H460 cells. The combination 16-2-16 (23b)/1a was found to be the most efficient mixture for transfection, even in the presence of serum, and >2 times better than Lipofectamine 2000™.

Chart 6. Quaternary ammonium geminis with alkyl spacer.

The related tetraalkyl diammonium surfactants with spacer length s = 3 (24a) and s = 6 (24b) and Cl– counterions, which can be considered to be gemini analogues of dioctadecyl-diammoniumchloride (DODAC), were tested for their efficiency in the transfection of baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells with luciferase.127 At lipid–DNA ratios higher than 2, 24b was more active than DODAC, both in the presence and absence of the helper lipid DOPE; 24a could only be tested without DOPE but was the least active at all ratios. All representatives of a series of quaternary ammonium geminis, 25, with ester links in the long tails, were more efficient in the transfection of human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line RD-4 with pEGFP-C1 than the commercial GenePORTER transfection agent,128 with the best results for n = 11 in the presence of DOPE (α = 0.33); the compound with n = 13 even showed some activity, albeit much reduced, in the absence of the helper lipid. Another variation in the long tail is the incorporation of aromatic moieties129 like in the gemini 26 and its conventional analogue 27. In the transfection of HeLa cells by GFP with helper lipid DOPE, the compounds with C16 tails (26c, 27c) were not very active; for the other compounds, there appeared to be hardly an advantage of the gemini structure, with the highest efficiency found for 26a (s = 3, 4, 5), 26b (s = 5), and 27a.

Geminis with Chol (Chart 2) as the hydrophobic part have also been studied. For the series of compounds 28 (Chart 6)130 the best activity was found for the compound with a s = 5 spacer, which, when formulated with DOPE, gave the best transfection efficiencies in HeLa and U373 cells. The efficiencies of the gemini surfactants 28 were better than those of the corresponding monovalent lipid 29 with DOPE. The hydroxyethyl Chol geminis 30 were all more effective in the transfection of HeLa cells with GFP than the monomer 31,131 and the analogue with s = 5 was most effective, at α = 0.33 and N/P 0.25 (0.5 in the presence of serum). Geminis with tocopherol (Chart 2) as the hydrophobic part 32 have also been prepared.132,133 The analogue with the shortest spacer, s = 3, was the best and even more efficient than Lipofectamine 2000 in the downregulation of GFP with RNAi in HEK293, HeLa, and Caco-2 cells, at α = 0.25 and 1.5 < N/P < 2.5, and without significant loss of cell viability;132 it was also the best in the transfection of Caco-2, HeLa, U251, HepG2, COS-7, BT-474, A549, CHO, and HEK293T cells with GFP at α = 0.25 and N/P 0.75.133

Of a new set of derivatives of dimeric surfactants (Chart 7) having aza- (m-5N-m, 33a; m-7N-m, 33b; m-8N-m, 34) and imino- (m-7NH-m, 35) substituted spacer groups, the activities of the C12-analogues were studied, and 12-7NH-12 (35a) was found to be comparable to Lipofectamine Plus™ in the transfection of COS-7 cells with luciferase, albeit at the cost of a slightly higher toxicity.134,135 Compared to 23, the interest of 35 is in the protonable amine at the centre of the -7N- spacer, and 35a–d were therefore compared to analogues of 23 with a spacer of the same length, but without the amine (23a–d with s = 7).136 Indeed the size of the aggregates of 35a–d was pH dependent, with smaller aggregates at higher pH, whereas those of 23a–c (s = 7) were pH-invariant. In the transfection of murine PAM 212 keratinocytes with luciferase, the activity increased going from 23 (s = 7) via23 (s = 3) to 35, which came closest to Lipofectamine Plus™; within each group, the activity increased in the order m = 12 < 16 < 18.

Chart 7. Quaternary ammonium geminis with other spacers.

Because of the tendency of surfactants with phytanyl tails (Phy, Chart 2) to give fusogenic hexagonal lipid packings,137 it was considered of interest to investigate gemini surfactants of type 23 with n = 3 and different alkyl tails, of which one is a phytanyl (23e–g, Chart 6).138 In the synthesis of these compounds, the stereochemistry of one of the centres in the phytanyl bromide building block is not controlled, which implies that, due to the presence of other chiral centres in the phytanyl chain, 23e–g are prepared and studied as mixtures of diastereoisomers. Compared to the analogues 23a–c with n = 3, the hydrophobic volume in 23e–g was much increased, causing a shift in the packing parameter P from values around 0.35, giving cylindrical micelles, to approx. 0.55, more consistent with vesicles. The asymmetric geminis 23e–g were more efficient than 16-3-16 (23b, n = 3) in the transfection of ovarian cancer cells OVCAR-3 with GFP, but not as active as Lipofectamine 2000™. In a subsequent study, these results were compared to those for the phytanyl analogues of 35a, viz.35d–f;139 this series turned out not to transfect OVCAR-3 cells, in spite of the aforementioned activity of 35a in COS-7134 and PAM 212136 cells.

The 12-7N-12 cationic gemini 35a was appended at the central N with amino acids (Gly, Lys) and dipeptides (Lys-Gly, Lys-Lys), for which the structure of 12-7N(Lys-Gly)-12 is given as an example (36a(Lys-Gly), Chart 7).140 In the transfection of COS-7 cells with interferon γ and DOPE as a helper lipid, optimum expression was reached after 72 h, with efficiencies decreasing in the order 36a(Gly) > 36a(Lys-Gly) > 36a(Lys) > Lipofectamin Plus™ > 36a(Lys-Lys) ≈ 35a. In the transfection of PAM 212 (murine keratinocytes) the activities of the 36a analogues were quite similar and much better than that of 35a although much worse than that of Lipofectamin Plus™; this standard performed very poorly with Sf 1Ep cottontail rabbit epithelial cells, where 36a(Gly) was the most efficient, followed by 36a(Lys-Gly) > 35a > 36a(Lys) > Lipofectamin Plus™ > 36a(Lys-Lys). The differences in efficiency of 35 and 36a for various epithelial cell types were ascribed to differences in the amount of proteoglycan on the cell surfaces. The presence of an amino acid/peptide in 36a is expected to soften the electrostatic interactions between lipoplex and proteoglycan by additional van der Waals and H-bond interactions, as compared to 35a, and the larger hydrophilic head group results in higher biocompatibility and (although not investigated) reduced toxicity. The cellular uptake of lipoplexes of 35a and 36(Lys-Gly) was not affected by the attempted selective inhibition of clathrin-mediated and caveolae-mediated endocytosis with respectively genistein and chlorpromazine, but much reduced by methyl-β-cyclodextrin, which affects both pathways.141 The transfection with interferon γ/GFP was affected by inhibition of the caveolae-mediated pathway for 35a but not for 36a(Lys-Gly), whereas inhibition of the clathrin-mediated pathway enhanced the transfection by 35a while slightly reducing that by 36a(Lys-Gly). It is proposed that with both surfactants, endosomal escape from caveolae is possible, but that 36a(Lys-Gly) can escape from clathrin-coated endosomes by a proton-sponge effect, due to the buffering by the Lys residue, whereas 35a can not. More recently analogues of 36(Lys-Gly)a–c with varying tail lengths were compared, with the best result for the C16-derivative 36b with DOPE at N/P = 2.5.142

The oxyethylene linker in 37143 is reminiscent of the aforementioned (section 2.1) neutral but hydrophilic PEG moieties, which can be incorporated in cationic lipid aggregates to prevent their aggregation with anionic biomolecules. In the transfection of HEK293T cells by pEGFP-C3, 37c was most efficient (α 0.7), and better than the Lipofectamin 2000™ standard, both in the presence and absence of serum, followed by 37a and 37b; 37b also gave the poorest cell viability results, although better than the standard, while 37a was the best in this respect. In a number of other cell types, viz. HeLa, CaCo-2 (human epithelial colorectal adenocarcinoma), Hep3B and MDA-MB231 cells, 37a was always the best, and 37b the poorest transfection agent. The analogue of 23b (16-6-16) with 2 S atoms in the 6 atom-spacer, 38-S-S-38, is an example of the aforementioned (section 2.4) disulfide dimers, which can be reduced in the reductive environment of the cell by the thiol compound glutathione, according to the reaction in Scheme 1A, in this case giving the monomeric, non-gemini surfactant 38-SH (Chart 7).144 It was demonstrated that glutathione can indeed split the S–S bond of 38-S-S-38 molecules in monolayers at the air–water surface, but reduction in the presence of DNA was much slower, resulting in a disappointing transfection activity. It is concluded that the S–S bond is not reduced effectively if it is in the hydrophobic part of the surfactant molecule. The transfection of COS-7 cells by GFP by the with m-phenylene gemini 39 with DOPE (α 0.2 or 0.5) was comparable to that of Lipo2000*; the corresponding monomer 40 was less effective at low α, and more toxic at low N/P.145

The series 41a–d with oxyethylene spacers of varying length and the Chol linked by an O atom were also investigated (Chart 7).146 All oxyethylene gemini surfactants were better than the monomer ‘half-gemini’ 31 in transfecting HeLa cells with GFP, with the best results for 41a (n = 1) and the worst for 41d (n = 5). A remarkable observation was that the transfection by 31 was strongly affected by the addition of 10% serum, whereas that by 41a–d was not. The analogues 42a–c (Chart 7) in which the Chol is not attached by an O but by a reducible disulfide bridge were tested for transfection of HeLa and HT1080 cells by GFP with DOPE, with practically no toxicity.147 The aromatic linker in 42b proved to be a disadvantage in this case, since the order of transfection efficiency was 42a ≈ 42c > 42b for HeLa cells, and 42a > 42c > 42b for HT1080 cells.

In compounds 43, the quaternary ammonium groups were linked by a redox-active ferrocenyl spacer. In the transfection of Caco-2, HEK293T, and HeLa cells with GFP, the compounds with the shorter (n = 5) were more active than those with the longer (n = 10) spacer, but less active than the analogues with just one quaternary ammonium/Chol group attached to the ferrocenyl.148 As in earlier studies on ferrocenyl-containing cationic lipids, the activity was abolished when the ferrocenyl group was oxidized,149 but for 43 it could be reinstated upon reduction of the lipoplex with ascorbic acid.

3.3. Carbohydrate geminis

Carbohydrates can be combined with lipids to give glycolipids, and given a positive charge to act as transfectants. This is of interest because many cell types have receptors for carbohydrate moieties,150 and the high level of hydration of carbohydrates possibly weakens the binding of the cationic ammonium groups to the DNA, thus facilitating its release. The series 44 (Chart 8), with the open-chain galactose-derived carbohydrate directly linked to the ammonium, showed transfection in CHO, COS-1, MCF-7 and A549 (human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial) cells, in particular with the C14 (44a) and C16 (44b) tails, while the related compound 45 with a longer spacer between head group and alkyl tail was not biologically active.151

Chart 8. Carbohydrate classical and gemini transfectants.

A series of geminis based on reduced glucose in which the spacer and alkyl tails were varied, was synthesized93 and tested for biological activity both in vitro and in vivo.152 Of the series with saturated tails 46a–h, the surfactants with hexadecyl tails 46e–f appeared to have the highest transfection efficiencies, comparable to Lipofectamine Plus2000™, for β-galactosidase in CHO-cells without a helper lipid, and the activity was slightly higher for the derivatives with s = 4 than for s = 6. The polar amine groups are procationic, and have an influence on each other, resulting in e.g. pKa values of 8.3 and 5.8 for 46i153 and pH-dependence of its aggregation behaviour and interaction with DNA.154 In a subsequent study, the glucose and mannose oleyl surfactants with alkyl (s = 6) spacers (46i and 46j) were compared to their counterparts with oxyethylene spacers (47a and 47c) and their amide analogue 47b.155 In the transfection of CHO-K1 cells with GFP, the activity decreased in the order 47a > 47c > 46j > 46i, with activity of 46i comparable to that of the standard Lipofectamine 2000™, while the amide 47b showed no activity; only 47c was less toxic than the standard.

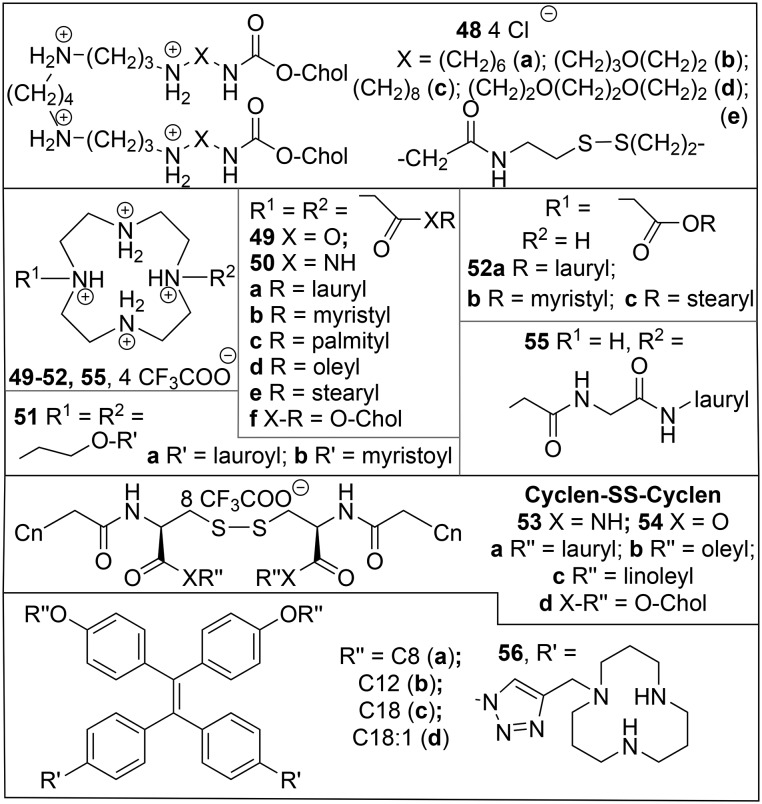

3.4. Geminis with multivalent head groups

The naturally occurring polyamine Sp (Chart 3) has been symmetrically appended with 2 Chol residues to give the compounds 48 (Chart 9).156 Compound 48a and its analogue featuring S–S bonds between the Chol and Sp moieties, 48e, were more active than the standard Lipofectamine 2000™ in the transfection of HEK293 cells by pEGFP-C2 plasmid with DOPE (α = 0.5) at N/P ratios >4.157 The activity of 48e was slightly lower than that of 48a and was abolished by extracellular glutathione, presumably due to reduction of the S–S bond, which would result in detachment of the cationic Sp head group of 48e from the hydrophobic Chol part. Other variations in the connection between Sp and Chol had subtle effects, with the best results for 48b (N/P 6) and 48d (N/P 8) in transfection of HEK293 cells as measured by the percentage of fluorescent cells resp. mean fluorescence intensity, and for 48c (N/P 8) in GFP silencing in BHK IR-780 cells.158

Chart 9. Geminis with multivalent head groups.

At N/P < 4 the cyclen-based gemini surfactants 49–50159 (Chart 9) were less toxic than Lipofectamine 2000™ in HEK293 cells. Their transfection activity was tested with luciferase (pGL-3) and eGFP (pEGFP-N1) plasmid DNA in HEK293 cells in the presence of the helper lipid DOPE. The amides 50 and the HO-Chol ester 49f were relatively inactive, and although for the other esters 49 the unsaturated 49d was slightly more active than its saturated analogue 49e, the highest activities were observed for the relatively short-chain (C12 and C14) derivatives 49a and 49b; of the reverse esters 51, the myristoyl analogue 51b was the most active. Of the single-chain analogues 52, 52a was internalized in spite of the relatively large size of its lipoplex, but nonetheless resulted in much poorer transfection than displayed by its gemini analogue 49a. Bioreducible geminis with 2 cyclen head groups, an S–S linker, and hydrophobic tails connected as amides (53) or esters (54) were also investigated in combination with DOPE (α = 0.33), and compared with a non-dimerizable single-chain analogue 55.160 All compounds 53–55 were less toxic than Lipofectamine 2000™ up to an N/P ratio of 8; the HO-Chol ester 54d was least toxic but also had the weakest interaction with DNA and was not further tested for biological activity. In the transfection of HEK293 cells with luciferase, the amides 53 were more active than the esters 54, with the activity decreasing in the order 53b (oleyl) > 53a (lauryl) > 53c (linoleyl) and 54b > 54a ≈ 54c. The activity of the best compound in this group, 53b, was close to that of Lipofectamine 2000™. Because of the generally lower activities of these compounds, the activity of the non-gemini 55 was only approx. 1 order of magnitude lower than that of its closest gemini analogue 53a. Quite recently, another cyclic multivalent head group, triazacyclododecane [12]ane-N3, has been linked by a triazole to a tetraphenylethylene platform with varying alkyl tails to give 56.161 The transfection of HepG2 cells by luciferase and DOPE decreased in the order 56b > 56a ≫ 56d > 56c and was in all cases less efficient than that by Lipo2000.

3.5. Geminis with delocalized charges

A strategy to overcome the toxicity problems of transfectants is to spread the positive charge of the cationic head. An early example is to use the amidine group like in diC14-amidine (Vectamidine, 57, Chart 10),162 which with PE as a helper lipid was active in the transfection of CHO and K562 cells with CAT. The guanidinium group in the amino acid arginine is a biological cationic group with delocalized charge; it has been coupled to DOTMA 2a, yielding Arg-DOTMA derivative 58,163 which gave good transfection of V79 (Chinese hamster lung) and HT29 cells. The positive charge can also be delocalized in a heterocyclic ring like pyridinium, as in the SAINT-2 (59, Chart 10, commercialized with DOPE as SAINT, Synthetic Amphiphile INTeraction)164 and Sunfish 60165 lipids.

Chart 10. Transfectants with delocalized positive charge.

The pyridinium surfactants generally have lower cytotoxicity than lipids with quaternized amine head groups, as shown also in a direct comparison of the pseudoglyceryl compound 3 (DOTAP) with its analogue with the quaternary ammonium group substituted by 2,4,6-trimethylpyridinium 61.166 Imidazolinium and imidazolium rings are other examples of heterocyclic rings in which positive charge can be delocalized. The latter was tested in the lipophoshoramidate framework (Chart 10),167 where the methylimidazolium compounds 62c and 62d were found to be more efficient and less toxic than the guanidinium compounds 62a and 62b. The developments of the lipophosphonates and lipophosphoramidates have been reviewed elsewhere.168

For pyridinium-containing geminis 63 (Chart 11A) related to 59, with 4 alkyl tails, the highest transfection efficiencies were found for a pentamethylene spacer (63, s = 3).164 In contrast to the transfection results of other gemini surfactants discussed above and below, pyridinium geminis were found to be less effective than their monomeric counterparts. For another group of geminis 64 the optimal spacer length for transfection of MCF-7 cells by luciferase with HO-Chol as helper lipid (α = 0.5, N/P = 2) was found to be a dimethylene spacer (s = 0), which was comparable to DOTAP; remarkably the transfection increased again at spacer lengths > s = 6.166 Insertion of nitrogens in the spacer of pyridinium geminis with varying nitrogen content (65vs.66a, which has Sp at the core of its spacer) and linker length (65a–c) did not improve the transfection of NCI-H23 (lung carcinoma) cells by luciferase with HO-Chol as helper lipid (α = 0.5, N/P = 2) compared to 64 (m = 0 or 8), and showed a similar bimodal dependence on spacer length: 66a > 65a > 65b > 65c (virtually no activity).169 Of derivatives of 66 where the nitrogens in the centre of the spacer had been amidated (66b, c) or alkylated (66d), only the latter was more active than Lipofectamine™, this time with a preference for DOPE (α = 0.5) as a helper lipid. Appending the central N in 64b with another amphiphilic pyridinium led to the unique ‘sesquigemini’ amphiphile 67, which was less active than 66d and Lipofectamine™, but was relatively indifferent to the presence or choice of helper lipid. Incorporation of a reducible disulfide in the spacer (68) resulted in loss of transfection activity, irrespective of the counterion (PF6– or Cl–) used.

Chart 11. Headgroups with delocalized charge, A) and C) pyridinium resp. imidazolium geminis; B) pseudogeminis.

The ‘pseudogemini’ surfactants are called this way because they have 2 alkyl tails but only one pyridinium head group; the other polar element is an ester (69) or amide (70) in the linker (Chart 11B). With N/P = 2 and DOPE (α = 0.5), these compounds gave transfection of NCI-H23 cells equivalent to that of Lipofectamine; the optimum alkyl chain length was the intermediate one (b) in both cases.170 The observed lower (virtually absent) cytotoxicity of the ester 69 compared to the amide 70 was tentatively ascribed to the different products expected to be formed by enzymic hydrolysis. For the pseudogemini analogue 71 in which the amide bond is reversed HO-Chol was a better helper lipid than DOPE, and the transfection activity at N/P = 2 decreased in the order 71c > 71a > 71b, with much reduced toxicity compared to 70.171

Following the success of oxyethylene spacers in other gemini systems (41,146 see section 3.2) the oxyethylene pyridinium geminis 72 (Chart 11A) with varying tail lengths were also prepared and tested.171 The transfection activity with DOPE (α = 0.33) at N/P = 3 increased with n, to a value for n = 16 higher than that found for Lipofectamine™. It was then attempted to take advantage of the excellent transfection efficiency of gemini 72 (n = 16), due to its membrane destabilization and its high charge/mass ratio, with the good transfection activity and somewhat reduced cytotoxicity of the conventional pyridinium surfactant 61b (a symmetric isomer of the pseudoglyceryl pyridinium compound 61a, see Chart 10), by studying mixtures of these compounds.172 The addition of 5–10% gemini 72 to 61b improved the transfection of NCI-H23 cells by GFP with DOPE 1a as the helper lipid (α = 0.33, N/P = 3). Moreover, there was evidence for a change in the endocytotic mechanism of uptake by the cell (see section 2.2): transfection by 61b/1a was inhibited by 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride (EIPA), which interferes with macropynocytosis, whereas transfection by 61b/72/1a was also inhibited by genistein, which interferes with the caveolae pathway. Interestingly, with HO-Chol as the helper lipid (0.33 < α < 0.50), the incorporation of 72 results in suppression of endocytosis involving clathrin, caveolae as well as macropinocytosis, which, in view of the improved transfection efficiency, suggest that yet another uptake mechanism operates in this case, possibly temporary poration of the cell membrane by 72. The results for this class of pyridinium surfactants where the head groups are connected by spacers directly attached to the quaternary nitrogen atoms have been reviewed.173

Another class of pyridinium geminis, 73a (Chart 11C), with long alkyl tails connected to the N in the pyridinium groups which are linked by spacers connected to the o-position, has been known for some time,174 but has only recently been used in transfection studies,175viz. of RD-4 cells by pEGFP-C1 with GenePORTER™ as a standard. The analogue of 73a with m = 2 (spacer length 4 CH2 groups) was approximately as active as the standard, and only marginally improved with DOPE as the helper lipid (0.33 < α < 0.67); AFM revealed that this was the only analogue of 73a that could condense DNA to particles with a diameter <100 nm. Of the other analogues of 73a given in Chart 11, only the one with p = 6 had some activity, and required DOPE (α = 0.5). The fluorinated analogues 73b all required DOPE (α = 0.33), and except for absence of any activity for p = 10, the dependence on the spacer length was completely different: the highest activity was observed for p = 6 (comparable to standard, lipoplex particles <100 nm), with much lower activities for p = 1 and 2.176

The imidazolium gemini 74a showed efficient transfection of HEK293 and HeLa cells with GFP with negligible cytotoxicity up to a concentration of 10–5 M (Chart 11D).177 The dependence of the transfection of HEK293 cells by GFP with DOPE as a helper lipid (α = 0.2) on the spacer length was investigated for the analogues 74b–e with C16 instead of C12 tails,178 and found to decrease in the order m = 0 (74b) > 3 (74d) > 1 (74c) > 10 (74e). In a comparison with the ammonium geminis 23b and 41 and the alkyl-spaced imidazolium gemini 74c, the oxyethylene analogue 75c was biologically the most active; all geminis included in this comparison outperformed the standard Lipofectamine 2000™. In a subsequent study179 the knockdown of EGFP by the appropriate siRNA in EGFP-expressing HEK293T cells was achieved, this time with a different helper lipid, i.e. mono-oleoyl glycerol.180

3.6. Amino acid and peptide geminis

Amino acids and peptides coupled to lipids are also used in transfection,181 for example in the aforementioned Arg-DOTMA derivative 58.163 Attachment of a stearoyl group to the N-terminus of the cell-penetrating peptides TAT, REV, FHV and R8 (stearoyl-HN-peptide-CO-NH2) improved the transfection of COS-7 cells with luciferase, with the best results, comparable to Lipofectamine, for R8.182 Stearoyl-appended R8 gave better condensation of the DNA, better adsorption to the cells, and better delivery to the nucleus than R8 itself;183 incorporation (10%) of the lipopeptide in liposomes led to uptake through macropinocytosis, resulting in less lysosomal degradation than in the case of clathrin-mediated endocytosis.184

The aforementioned polyamine Sp (Chart 2) can be symmetrically connected by amide bonds to an amino acid/peptide and oleic acid in two different ways (Chart 12), i.e. with the peptide at both terminal N, and the oleoyl at the central N atoms (76), and the other way around (77).115 The transfection of a number of cells, CHO-DG44, C2C12 (mouse muscle), nonadherent MOPC315 (mouse tumor), and 1321N1 (neuronal) with luciferase by the Lys derivatives 76a and 77a and the peptides 76b and 77b was compared to that by Lipofectamine 2000™. For all cell types, the geminis of type 77 were more active than 76. The peptide derivative 77b was more active than the Lys-derivative 77a except for the C2C12 cells where it was the other way around. The gemini surfactants were superior to Lipofectamine 2000™ except for the 1321N1 cells where they performed relatively poorly. In a subsequent study on analogues of 77a,183 it was found that the Lys head group was superior to alternative amino acids with 2 amino groups, l-Orn, l-Dab (2,4-diaminobutyric acid), and l-Dap (2,3-diaminopropionic acid), in the transfection of HEK293 cells with luciferase; the d-Lys analogue appeared to be both slightly more active and less toxic than l-Lys. Of a series of analogues of 77a with an oleoyl and one other tail (C6, C10, C14, C18, C18:1, and C18:3) those with 2 tails with 18 C atoms were the most active, with activity decreasing in the order C18 > C18:1 > C18:3 for the other tail. The cyclospermin 78 showed a remarkable dependence on the nature of the links between the Lys residues in the peptide; compound 78a with an ε-link only between the 1st and 2nd Lys was one of the most active compounds, whereas the analogue 78b with ε-links between all Lys residues was not active at all.50

Chart 12. Amino acid-based gemini surfactants. Links between Lys in peptides are α unless otherwise indicated.

Peptide geminis with Cys-Ser-alkylamine at the core linked by an ethylene bridge between the Cys-S, which are remotely related to the dimerizable cationic surfactant 20,103 have also been investigated.50,184,185 Of a series of compounds with C16 tails 79, the ones with head groups consisting of a single (di)amino acid, Dab 79a and Lys 79c were not active in the transfection of CHO cells with luciferase;184 for a series of peptide headgroups, the activity decreased in the order  79d > (Lys)2Lys 79e > Lys-Ser 79b. The transfection of CHO-K1 cells with β-galactosidase by 79d was improved by addition of either DOPE or Lipofectamine Plus™, and even more by both. In a subsequent investigation, the C18:1 analogues 80 turned out to be even more active than the C16 compounds 79 and much more than the corresponding C12 compounds, and the effect of the linkage, α or ε, was systematically investigated for head groups consisting of 3 Lys residues.185 The activity of these compounds in the transfection of CHO-DG44 cells without DOPE was compared to that of Lipofectamine Plus™ and found to decrease in the order 80d (ε,ε) > 80c (ε,α) > 80b (α,ε) > 80a (α,α) > 80e ((Lys)2Lys);50 compounds 80d and its C16 analogue as well as 80c were more active than Lipofectamine Plus™.185 These results can however not be generalized in the sense that for trilysine head groups all links should be ε, because of the aforementioned opposite result for the cyclospermine 78. The gemini character of compounds 80 is important for transfection, as demonstrated by the fact that compound 81, which is the ‘half-gemini’ analogue of 80b, is not active.50

79d > (Lys)2Lys 79e > Lys-Ser 79b. The transfection of CHO-K1 cells with β-galactosidase by 79d was improved by addition of either DOPE or Lipofectamine Plus™, and even more by both. In a subsequent investigation, the C18:1 analogues 80 turned out to be even more active than the C16 compounds 79 and much more than the corresponding C12 compounds, and the effect of the linkage, α or ε, was systematically investigated for head groups consisting of 3 Lys residues.185 The activity of these compounds in the transfection of CHO-DG44 cells without DOPE was compared to that of Lipofectamine Plus™ and found to decrease in the order 80d (ε,ε) > 80c (ε,α) > 80b (α,ε) > 80a (α,α) > 80e ((Lys)2Lys);50 compounds 80d and its C16 analogue as well as 80c were more active than Lipofectamine Plus™.185 These results can however not be generalized in the sense that for trilysine head groups all links should be ε, because of the aforementioned opposite result for the cyclospermine 78. The gemini character of compounds 80 is important for transfection, as demonstrated by the fact that compound 81, which is the ‘half-gemini’ analogue of 80b, is not active.50

Another group of gemini surfactants based on lysine, viz. (R1(CO)-Lys(H)-NH)2(CH2)n82 (Chart 12),186 has a fatty acid (R1(CO)) connected to the α-amino group, and the carboxylic groups linked by diamine spacers of length n. The first report50 on 82 referred to products that may have contained up to 10 stereoisomers, due to the use of technical (Z/E mixture) oleic acid, combined with a racemization-prone synthetic protocol; this strategy was revised, starting from pure oleic acid.186 For spacer length n = 6 the hydrophobic acyl tail was varied in length (R1 = C8 to C18, 82d–i), and, for R1 = C18, the degree of unsaturation (C18:1 Z82a and E82b, C18:2 (Z,Z) 82c). For R1(CO) = oleoyl (C18:1 Z) the spacer length (n = 2–8, 82j–k, 82a) and the stereochemistry of the lysine building block (d-Lys, 82o) were varied; a ‘half-gemini’ derivative 83 with a single oleoyl tail and head group was also prepared. In the transfection of HeLa cells with β-galactosidase, with or without DOPE, the oleoyl derivative (C18:1 Z, 82a) was by far the best compound in this series. There was also a slight improvement with the change of Lys stereochemistry in 82o, such as also found for the aforementioned Sp derivative 78a. Without DOPE, the oleoyl derivative with n = 6 (82a) was far more active than those with n = 2–5 (82j–n) or n = 8 (82m), making this, along with the glycolipid 46i and the lipopeptide 80d, one of the most active compounds to come out of the ENGEMS project;50 with DOPE, there was hardly an effect of spacer length, except a slightly lower activity for n = 3 (82k). The gemini structure of 82a was essential; its ‘half-gemini’ analogue 83 was less active by 2 orders of magnitude.

Related to 79 and 82 is the disulfide dimer 84 of a Lys-Cys peptide that is esterified at its C-terminus with oleyl-alcohol;187 this showed no toxicity against HEK293 and HeLa cells like the standard Lipofectamine RNAiMAX™, but it gave more efficient silencing of the protein kinase MEK1 with RNAi. The aggregates of 84 formed lipoplexes with siMEK1, in which the RNA was protected from degradation in serum, and from which it could be released by reduction of the S–S bond by dithiothreitol. In a subsequent report188 the activity of 84 was compared to its non-reducible analogue with a single –CH2– group in the place of the –S–S– functionality in 84, and with its non-dimerizable ‘half-gemini’ analogue Lys-Ala-oleoyl in the silencing of EGFR in MCF-7 and HeLa cells. The half-gemini compound was both less active and more toxic. The lipoplexes of both geminis (N/P 10) were taken up in MCF-7 cells by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Although the uptake of lipoplexes of 84 was less or equally efficient in respectively MCF-7 and HeLa cells than that of the –CH2– analogue, the silencing was equally resp. more complete for 84; this effect was ascribed to reduction of the S–S bond upon uptake, resulting in more efficient release of the siRNA from the lysosome. The efforts in this field have been reviewed at an early stage50 as well as more recently.112

Of the multivalent protonable amphiphilic peptides represented by general structure 85 (Chart 12), EHCO (85a) stood out as particularly effective, at N/P values in the range 8–10 and without helper lipid, in the silencing of luciferase in U87-luc cells.189 This was explained by its hemolytic activity at pH 5.4, but not at 6.5 and 7.4, which indicates that it will selectively disrupt endosomal membranes at the pH of the transition to lysosomes. In a study where EHCO (85a) was applied to silence the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α) in U87 glioblastoma cells, it was shown by confocal laser microscopy that Alexa Fluor 488-labeled siRNA had indeed escaped from the lysosomes.190 Hemolytic activity is not the only important factor for transfection activity, since CHO-GFP and HT29 were better transfected at N/P 12 by the histidine-free lipopeptides ECO (85b) and ECLn (85c), which is tentatively explained by an assumed tendency for the His-containing EHCO (85a) to take up a cylindrical shape, which would favour bilayer over non-bilayer structures.191 In this connection it was shown that oxidative polymerization of the 2 thiols in ECO (85b) upon lipoplex formation protects the siRNA in the lipoplex from degradation, and that it is released upon reduction by glutathione (see section 2.4).192 The cysteine thiol in EHCO (85a) can also be used to enhance selective delivery, for example by maleimide conjugation to a PEG-ylated peptide, to target cancer cells in which the bombesin receptor is overexpressed.193 The results for these lipopeptides have recently been reviewed.194

4. Asymmetric geminis and beyond

4.1. Gemini surfactants with chiral spacers

Some cationic gemini surfactants bear one or more chiral centers in the spacer group, which can lead to asymmetry in the molecular structure. Tartaric acid has a 4C-skeleton with 2 chiral centres. In an early example (Chart 13),195 the hydroxy groups of the L- or (R,R)-enantiomer were esterified with palmitic acid, while the carboxylic acid groups were linked by an amide bond to one of the amine groups of 1,2-diaminoethane (86a), the α-amino group of the amino acid lysine (86b), or a combination of both (86c). Compared to the other gemini surfactants studied in the European Network on Gemini Surfactants (ENGEMS) project (see below), the activity of the compounds 86b and 86c in the transfection of CHO-K1 cells with luciferase plasmid DNA was moderate, while the toxicity, disappointingly, was more than average; compound 86a was not active at all. More recently, a set of novel geminis based on tartaric acid, with the carboxylic acid groups esterified with alkyl (C12, 87a; C16, 87b) alcohols, and the hydroxyl groups with aminocaproic acids was investigated in Hek293T and HeLa cells,196 and found to give GFP expression comparable to or better than DC-Chol 8a and DOTAP 2b, with significantly lower toxicity. The efficiencies of the mixed aggregates composed of the neutral helper lipid 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) and the stereoisomers of the cationic dimeric surfactant with 2 chiral centres in the spacer, 2,3-dimethoxy-1,4-bis(N-hexadecyl-N,N-dimethylammonium) butane dibromide 88 (88a, (2S,3S); 88b (2R,3R); 88c (2S,3R)), as transfection vectors were tested using the eGFP coding plasmid and COS-1 cells.197 In these systems, only 88c was more efficient than Fugene, and it also showed the lowest toxicity, whereas the half-gemini analogue of 88, consisting of one of the surfactant tails and head groups with a 2-methoxyethyl group instead of the spacer, had no transfection activity at all.

Chart 13. Geminis with chiral spacers.

Gemini-like amphiphilic peptides consisting of a peptide spacer with the N- and C-termini appended with hydrophobic groups are also to be considered ‘geminoids’.119 As an example, the SPKR peptide (89-SPKR, Chart 13, with R1, R2, R3, R4 representing the Ser, Pro, Lys and Arg side chains, respectively) inspired by biological nucleic acid binding motifs,52,198 was appended with unsaturated (oleoyl/oleyl) alkyl tails. The versatility of the chemical approach allowed peptides related to SPKR to be studied, and it was found that the Pro and at least one of the cationic (Lys, Arg) residues are essential for the biological activity. 89-SPKR and the analogue 89-APKR showed excellent plasmid DNA transfection of HeLa and Hek293T cells with GFP, and quenching of GFP by siRNA in 1207 human bladder carcinoma cells transfected with GFP, with only a moderate cytotoxic effect. Importantly, this can be achieved without the addition of a lysogenic helper lipid, provided that the lipid tails contain unsaturations.

Analogues of the gemini amphiphilic peptides 85194 in which a lysine residue (K) is connected to other amino acids at both (α and ε) amino groups as in 90 and 91 are also asymmetric and fall under the geminoid definition. Of the 2 ethylenediamine derivatives EKHCO (90a) and EHHKCO (90b), the hemolytic activity of the former showed the largest increase at lower pH (5.5) and displayed the larger transfection activity, at N/P = 12 for U87 glioblastoma cells with pCMV-luciferase.199 The derivatives 91 with the Sp headgroup (Chart 3) were studied in the silencing of the U87-Luc cells with N/P = 12.200 For the compounds without β-Ala (z = 0), the activity increased in the series 91c < 91d < 91a < Lipofectamine 2000 < 91c; the activities of the β-Ala (z = 1) containing analogues 91d–h were slightly lower and followed the same order, except for 91h which was the most active of all compounds 91.

4.2. Lipidoids

New cationic lipids for transfection have not only been explored by design but also by combinatorial approaches. In one such approach, a number of polyamines have been reacted with acrylamides with amine residues of varying chain length (Scheme 2A), and the crude products, coined ‘lipidoids’, tested for their activity in the silencing of HeLa cells transfected with luciferase by siRNA.201 Not surprisingly, some gemini products, such as 92a (64N-16) and its C15-analogue, were found to be very effective. Interestingly, some of the products of more complex amines and acrylamides with shorter (C12) tails, such as 98N-12, turned out to be even more active, in particular with 5 tails attached (92b). In combination with HO-Chol and PEG-lipid, this compound was particularly effective in silencing the expression of the blood-clotting Factor VII, which can be detected in serum, by mouse hepatocytes. In a formulation with HO-Chol and PEG-lipid, 92b could also silence the expression of apolipoprotein by hepatocytes in cynomolgus monkeys; the mass of material relative to the siRNA in this experiment was approx. one third, with fewer components, of that in the aforementioned experiments67 with SNALP with 3b.

Scheme 2. Lipidoids from A) acrylates, B) epoxides, C) rings.

In another combinatorial study involving acrylate esters in addition to acrylamides, the methoxy compound 93a was found to be most active in luciferase silencing in HeLa cells, with however low cell viability.202 The result of factor VII silencing in mice was better for the alcohol 93b, with >80% knockdown at 12 : 1 lipid/siRNA weight ratio. In another study, the combination of the amide 93c with the C13-acrylate analogue of 93b (98O-13), which are each individually not active, was found to be synergistic in this factor VII silencing.203 The bioreducible analogue 93e with an S–S bond in the acrylate was found to be very effective in silencing GFP in MDA-MB-231 cells expressing this protein.204

In the exploration of more combinations of amines with acrylate esters, it was found that lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) of DSPC (1d), HO-Chol, PEG-lipid and any of the lipidoids 94a, 94c, and 94d were also very active.205 Based on the result that the optimum alkyl tail length and substitution number were 12–13 and 4, respectively, the next generation of lipidoids was developed within the same study, which yielded 94e as the most effective compound. The most active lipidoids in the silencing of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in human colorectal adenocarcinoma (Caco-2) cells were 94b, 94d and 94f.206,207 The 3-tailed version of 94b was also applied in the silencing of the anti-apoptotic protein Mcl1, which resulted in apoptosis of mantle cell lymphoma cells,208 and of tumor necrosis factor α in a macrophage-fibroblast model for diabetic foot ulcers.209

In another combinatorial approach, amines were reacted with racemic alkyl epoxides of varying tail lengths (Scheme 2B) to give the substituted aminoalcohol products 95 as mixtures of diastereomers.210 Following initial screening by silencing of luciferase in HeLa cells, the compounds 95a–c were identified as being most effective in factor VII silencing in mouse hepatocytes, with no evidence of adverse effects. In a formulation with DSPC, HO-Chol, and PEG, compound 95c was found to be more potent by two orders-of-magnitude than the best acrylamide lipidoid 92b. For the correlation between activity in vitro and in vivo, the RNA entrapment efficiency had a higher predictive value than the zeta potential and the particle size, provided that the latter was <200 nm.211 In a microscopic study of the transfection by LNPs based on 95c of mouse embryonic fibroblasts with or without NPC1 (Niemann-Pick type C1 glycoprotein), it was found that transfection was more efficient without NPC1, implying that this protein is responsible for exocytosis of 70% of the nucleotide.212 In a study where 95c-LNP loaded with m-RNA for erythropoietin (EPO) were intravenously injected in mice, the EPO level in serum was raised by including the classical helper lipid DOPE (1a) instead of DSPC (1d) in the formulation.213 LNPs with lipopeptide lipidoids are called lipopeptide nanoparticles (LPNs). In a study where amine groups incorporated in amino acid derivatives were reacted by reductive amination, Michael addition to acrylate esters, and epoxide opening, the particularly effective compound cKK-E12 (95d), derived from the reaction of diketopiperazine of the amino acid lysine with the C12-epoxide, was found to be particularly effective and selective in the silencing of factor VII in mouse hepatocytes, also when compared to 92b and 95c.214 LPNs based on 95d were also successfully applied to deliver mRNA vaccines to B lymphocytes of the immune system in the spleen of mice to enhance their cytotoxic response to a melanoma tumor.215 In a study on the transfection of mice with the mRNA for EPO, the activity of the linoleyl analogue OF-02 (95e) was even higher.216

Lipidoids have also been used with DNA, for example 14N-87 (92d), which was more active than the standard Lipofectamine 2000 in the transfection of HeLa cells with β-galactosidase.217 Related to the diketopiperazine platform of 95d is the triazine in 96, which was applied in simultaneous transfection of pDNA and siRNA, viz. expression of GFP and silencing of luciferase in HeLa cells.218

5. Conclusions and outlook

The past decade has seen tremendous progress in the development, by design and synthesis as well as combinatorial approaches, of lipid-based vectors for DNA and RNA delivery. In this review, the emphasis was on gemini and gemini-like surfactants, which proved to be more effective than their single head group/single tail counterparts in many (but not all) cases where a comparison could be made. The spacer/linker region offers an important additional source of variation/optimization in geminis that is not available to classical surfactants.

In the design of vectors, many aspects of molecular and aggregate structure must be considered. Electrostatics must be balanced with respect to the interaction with the polynucleotide and the target cell; the lipid should preferably be biodegradable and its positive charge delocalized to minimize cytotoxicity. Advantage can be taken of concepts from biology, such as recognition of carbohydrates and peptides by cellular receptors, as well as specific peptide sequences which are used for DNA binding and cell-penetration, and are also being explored for endosomal escape219 and nuclear localization.220 In our review, the emphasis has been more on the exploration of chemical space, but it should be noted that insights in physicochemical concepts, such as surface charge density, effective charge density, lipoplex polymorphism and fusogenicity have also been developed; their impact on nucleic acid complexation, cellular uptake, endosomal escape, cytoplasmic mobility, and nuclear entry has been reviewed elsewhere.39,113,221,222 Cationic lipids already are used in laboratories for biological research purposes on a large scale, and recent surveys37,223 mention clinical trials with liposomes or LNPs for various therapies, viz. with plasmid DNA for (among others) cystic fibrosis, various lung cancers, various squamous cell carcinomas, glioblastoma, and with siRNA for amyloidosis, muscular dystrophy, neuroendocrine tumor and adrenocortical carcinoma, liver and pancreatic cancer, and hepatic fibrosis.