Merlin deficiency elicits the co-operative activity of the Hippo and TGF-β pathways to disengage restriction on STAT3 and hexokinase 2, enabling a metabolic shift towards aerobic glycolysis. Merlin-deficient tumors may be effectively targeted with STAT3 inhibitors.

Abstract

The NF2 gene encodes the tumor and metastasis suppressor protein Merlin. Merlin exerts its tumor suppressive role by inhibiting proliferation and inducing contact-growth inhibition and apoptosis. In the current investigation, we determined that loss of Merlin in breast cancer tissues is concordant with the loss of the inhibitory SMAD, SMAD7, of the TGF-β pathway. This was reflected as dysregulated activation of TGF-β signaling that co-operatively engaged with effectors of the Hippo pathway (YAP/TAZ/TEAD). As a consequence, the loss of Merlin in breast cancer resulted in a significant metabolic and bioenergetic adaptation of cells characterized by increased aerobic glycolysis and decreased oxygen consumption. Mechanistically, we determined that the co-operative activity of the Hippo and TGF-β transcription effectors caused upregulation of the long non-coding RNA Urothelial Cancer-Associated 1 (UCA1) that disengaged Merlin’s check on STAT3 activity. The consequent upregulation of Hexokinase 2 (HK2) enabled a metabolic shift towards aerobic glycolysis. In fact, Merlin deficiency engendered cellular dependence on this metabolic adaptation, endorsing a critical role for Merlin in regulating cellular metabolism. This is the first report of Merlin functioning as a molecular restraint on cellular metabolism. Thus, breast cancer patients whose tumors demonstrate concordant loss of Merlin and SMAD7 may benefit from an approach of incorporating STAT3 inhibitors.

Introduction

As the end-product of glucose catabolism, pyruvate is mainly converted to acetyl-CoA in cells under normoxia. Acetyl-CoA initiates the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) that generates coenzymes for ATP production through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), among other components. Under hypoxia, pyruvate is primarily converted into lactate via anaerobic glycolysis. In cancer cells, even under proper oxygen-supplied environment, pyruvate is preferentially processed into lactate via aerobic glycolysis. Although aerobic glycolysis releases less ATP, it is still advantageous since it is a fast-rate process that increases glucose uptake and produces abundant intermediate precursors to the generation of NADPH, ribose-6-phosphate, amino acid and lipids necessary to fuel the high biomass state of malignant cells (1). Furthermore, release of a high amount of lactate acidifies the tumor milieu and contributes to a favorable tumor microenvironment (2). Genetic aberrations in TCA cycle enzymes, such as mutations in fumarase and downregulation of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase by promoter hypermethylation, have been reported in breast cancer (3). These alterations likely contribute to the metabolic shift in breast cancer. However, the TCA-OXPHOS path is not fully inoperative in cancer cells. Despite its lower activity, it still cooperates with aerobic glycolysis to better fulfill the energy requirements of cancer cells.

Merlin is a tumor suppressor encoded by the neurofibromin 2 (NF2) gene. Merlin is a member of the 4.1 protein, ezrin, radixin, moesin (FERM) domain family of proteins and exerts its tumor suppressive role by inducing contact-growth inhibition and apoptosis (4). Merlin also was demonstrated to inhibit proliferation by downregulating cyclin D1 (5). Merlin is primarily known for its loss in benign tumors of the nervous system, such as schwannomas, meningiomas and ependymomas, characterizing the Neurofibromatosis 2 disorder (4). The loss of Merlin has also been reported in malignancies such as mesothelioma, melanoma and breast cancers (6–8). While there are no significant mutations detected in NF2 transcript levels, the protein levels of Merlin are reduced in advanced and metastatic breast cancer. This downregulation of Merlin was identified to be the outcome of osteopontin-induced activation of protein kinase B (AKT) signaling that marks Merlin for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (8). Moreover, in both, breast and pancreatic cancers, Merlin targeted the Wnt pathway transcription co-factor, β-catenin, for degradation, consequently reducing the abundance of nuclear β-catenin (9). In addition, Merlin loss led to accumulation of reactive oxygen species in breast cancer cells which consequently caused dysregulated activation of Hedgehog signaling (10).

Homozygous knockout of NF2 is embryonically lethal in mice by day 7 of gestation, displaying poorly structured extraembryonic ectoderm (11). Heterozygous knockout mice survive but typically develop multiple cancers with increased metastatic events (12). Specific conditional NF2 knockout mouse models targeting Schwann cells, keratinocytes, hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells have been generated for the study of schwannomas, epidermal and liver development, respectively (13–15). In addition, an approach for inducible knockout of NF2 has been applied to investigate the role of NF2 in the hematopoietic compartment and kidney tumorigenesis (16,17).

Merlin is an upstream activator of the Hippo signaling pathway that is well recognized for its role in organ size control by repressing cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. Activation of Hippo signaling leads to phosphorylation of Yes-associated protein (YAP)/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) co-transcriptional factors that are retained in the cytoplasm or degraded. Upon loss of Merlin, the Hippo pathway is inactivated, YAP/TAZ are free to translocate to the nucleus, associate with TEA domain transcription factor (TEAD) transcriptional activators and activate target genes (18). Active YAP/TAZ plays an important role in the activation of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling in the maintenance of human embryonic stem cells. YAP/TAZ bind to active TGF-β effectors, SMAD2/3–4 in the nucleus, enabling the accumulation and accommodation of a complex that triggers TGF-β-target genes. A cross-talk between nuclear YAP/TAZ and TGF-β signaling revealed convergent roles for signals that coordinate a specific pro-tumorigenic transcriptional program (19). In the current study, we investigated the relationship between loss of Merlin with decreased expression of SMAD7 in patient-derived breast tumors corresponding to advanced breast cancer. Our investigations have revealed co-operative transcriptional activities of YAP/TAZ/SMAD that facilitate glycolytic metabolic adaptation of Merlin-deficient breast cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The ER+PR+Her2- MCF7 breast cancer cell line resembles luminal A breast cancer (obtained from ATCC, Manassas, VA). MCF10AT is an immortalized, triple negative breast epithelial cell line transformed by transfection with T24 c-Ha-ras oncogene (obtained from Karmanos Cancer Center). The triple negative SUM159 cell line was obtained from Asterand Biosciences (Detroit MI). Cells, including stable transfectants for knockdown or re-expression of Merlin, were cultured as previously described (8–10).

Cells were treated with 4 μM TGF-β type I receptor inhibitor A8301 (Stemgent, Lexington, MA), 1 μM phospho-AKT inhibitor MK2206, (Selleckchem, Houston, TX) or 2μM phospho-STAT3 inhibitor STATTIC (Selleckchem) using DMSO vehicle (Fisher Bioreagents, Fair Lawn, NJ).

Cell line authentication

All cell lines were validated for authentication using STR based assays of genomic DNA from the cell lines. The results of the assays were compared/validated using ATCC-STR database. Cell lines were authenticated when acquired and before cells were frozen in early passages, while the culture was actively growing. Cells were replaced from frozen stocks after a maximum of 12 passages or 3 months continuous culture. Cell lines were periodically confirmed negative for mycoplasma contamination using PCR assays.

Transwell invasion assay

Cells were pre-treated with STATTIC or DMSO and seeded in serum-free growth medium containing the respective treatments in BioCoat™ Matrigel® Invasion Chambers (Corning, Bedford, MA). Serum-free growth medium with fibronectin was added to each well containing the chamber insert. Cell-containing inserts were incubated in 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 16h then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with crystal violet for 10 min and rinsed with deionized water. Photographs of inserts were taken using Nikon Eclipse Ti-U microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using 10× objective. Each experimental condition was performed in duplicate and four random fields of each insert were recorded. Area of invaded cells was measured by ImageJ.

3D culture

Cells were pre-treated with STATTIC or DMSO and seeded in growth media supplemented with 2% 3D Culture Matrix Reduced Growth Factor Basement Membrane Extract (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) in a chamber cover glass slide (Millipore, Billerica, MA) pre-coated with 3D Culture Matrix Reduced Growth Factor Basement Membrane Extract. The chamber slide was incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C with media replacement at every 4 days. Morphology was registered using Nikon Eclipse Ti-U microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) 20× objective.

UCA1 silencing

Cells were transfected with 50 nM control-siRNA or UCA1-siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) overnight following the protocol of Lipofectamine® 2000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were lysed 48 h post-transfection with NP40 lysis buffer (150 Mm NaCl, 50 mM TRIS, 1% NP40) and total protein solution quantified using Precision Red Advanced Protein Assay (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO).

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was harvested using the RNeasy MiniKit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and complementary DNA was synthesized according to the High Capacity complementary DNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Vilnius, Lithuania). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was conducted with the TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystem, Austin, TX) and data analyzed with the 2−∆∆Ct method. Primers for the genes of interest (GLUT, MCT, LDH, CTGF, CYR61 and UCA1) and control (ACTB) were purchased from Applied Biosystems.

Western blotting analysis

Protein lysate was collected using NP40 lysis buffer and immunoblotted using the following antibodies: phospho-SMAD2 [Ser465/467]/SMAD3 [Ser423/425)], SMAD2/3, SMAD4, SMAD6, phospho-YAP, TAZ, GAPDH, phospho-AKT [Ser473], pan-AKT, phospho-STAT3 [Tyr705], STAT3, Hexokinase 2 and HSP90 (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); SMAD7 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), phospho-TAZ [Ser89] (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas) and β-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Glucose consumption and lactate production assays

Glucose and lactate levels in conditioned culture media were measured using the Amplex Red Glucose/Glucose Oxidase Assay Kit (Invitrogen) and Lactate Colorimetric/Fluorometric Assay Kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA), respectively.

Bioenergetics assessments

For extracellular flux assays (XF assays), cells were seeded at a density of 4 × 104 cells/well 24 h prior to the assay. XF assays were performed in the same aforementioned basal media without bicarbonate supplementation and with 0.5% fetal bovine serum, pH 7.4. The buffer capacity of each media was determined prior to the assay. Cells were equilibrated in a non-CO2 incubator for one hour before measurement of oxygen consumption rates (OCRs) and extracellular acidification rates (ECARs).

Targeted metabolomics

Cells (3 × 106 cells/10 cm petri dish or 1.5 × 106 cells/10 cm petri dish) were treated with 2 µM of STATTIC inhibitor for 48 h or silenced for UCA1 (siRNA-UCA1), respectively. DMSO and non-targeting siRNA were used as respective controls. Cells were briefly washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, scraped in ice-cold methanol and incubated on ice for 30 min. One volume of ice cold methanol was added and cell lysate was centrifuged at 12,000× g at −10°C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and taken for analysis. A separate culture of each condition was also maintained for protein lysate collection and concentration measure for further normalization. Kreb’s Cycle components were analyzed by liquid-chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) as previously described (20). Peak areas of metabolites in the sample extracts were compared in MultiQuant software (Sciex, Redwood City, CA) to those of known standards to calculate metabolite concentrations. Calculations for concentrations of structural isomers, G6P and F6P, which share mass transitions and co-elute were determined by a previously published method (21). Metabolite concentration was normalized by protein concentration.

Anchorage independence growth assay

A 6-well plate was coated with DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.1% insulin mixed with 1.5% BD BACTO™ Agar (Beckton Dickson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) (1:1 ratio). Cells were seeded at a density of 3000 cells/well in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 10 ug/ml insulin mixed with 0.7% bacteriological agar (1:1 ratio). After 24 h, medium containing STATTIC was added to designated wells. Colonies were enumerated after 10–14 days.

Reporter assays

Cells were plated in 96-well plates and transfected with 50 ng of 8xGTIIC or SBE4 or STAT3 luciferase reporters (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) using FuGENE 6 Transfection Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI). The media was changed to regular growth media 24 h post-transfection. The assay was terminated 32 h post-transfection and read using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega).

Immunohistochemistry

Breast tumor tissue microarrays from the NCI Cooperative Breast Tumor Tissue Resource were immunohistochemically stained for Merlin and SMAD7 (Supplementary Table 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The University of South Alabama Institutional Review Board granted this study an exemption from ethics approval. Specifically, immunohistochemical staining was performed using the streptavidin biotin complex method with 3,3ʹ-diaminobenzidine chromogen LSAB+ System-HRP reagents (K4065) (DAB) (which included a 3% hydrogen peroxide peroxidase block) in a Dako Autostainer Plus automated immunostainer (Glostrup, Denmark). Heat induced antigen retrieval was performed with EDTA buffer, pH 8.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific PT Module Buffer 2) for Merlin and with sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific PT Module Buffer 1) for SMAD7. Blocking was performed with an avidin/biotin blocking kit (SP-2001; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The following antibodies were used: Merlin: NF2 (A-19), and SMAD7 (H-79) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The intensity of cytoplasmic staining was quantitated with computer-assisted image analysis in a Dako ACIS III Image Analysis System (Glostrup, Denmark). Images were captured at 20× magnifications by the DS-L4 Microscope Camera Control unit using a NIKON Eclipse E200 microscope.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was conducted using JMP Pro 13.0 (product of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Significance level of 0.05 was used to determine significance of results. Parallel dotplots and boxplots were used to compare distribution of Merlin and SMAD7 values by different clinical parameters (grade, stage, metastatic status and nodal involvement) to compare graphically and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare means of by groups. Dunnett’s comparison with control method was used to compare means of different levels with that for normal breast tissue. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to establish linear association and least squares regression technique was used to estimate linear relation.

Results

Loss of Merlin in advanced breast cancer tissues is concordant with loss of SMAD7

We evaluated the expression of Merlin and SMAD7 by immunohistochemical staining of breast tumor tissue microarrays. As represented in Figure 1, the staining intensities for Merlin and SMAD7 were significantly decreased in breast tumors when analyzed by the grade (I, II or III) (Figure 1A and B), nodal involvement (N0, N1 or N2) (Figure 1C and D), metastatic status (M0 or M1) (Figure 1E and F) or disease stage (Figure 1G and H). While normal breast tissue stained intensely for Merlin (Figure 1I; a, c) and SMAD7 (Figure 1I; b, d), tumor tissues showed characteristically reduced staining for both proteins (Figure 1I; e–h). The staining for Merlin was largely cytoplasmic with a medium level of nuclear staining. In contrast, SMAD7 was predominantly nuclear. This is consistent with its role as a transcription co-repressor (22). When the mean immunohistochemistry (IHC) scores for Merlin and SMAD7 were computed with respect to tumor stage, it was evident that there is a very strong positive linear relation between them (R2 = 0.97, ANOVA p = 0.0003). The resulting least squares regression line represents mean (Merlin) = −83.15 + 20.17*Mean (SMAD7), with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient r = 0.985 (Figure 1J and Supplementary Table 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Collectively, the data demonstrate that the loss of Merlin and SMAD7 are concordant events.

Figure 1.

Loss of Merlin is concordant with the loss of SMAD7 in breast cancer. Breast tumor tissue microarrays were stained by immunohistochemistry for the expression of Merlin and SMAD7. The staining intensity is depicted as an IHC score. (A, B) represent the scores of Merlin and SMAD7 with respect to the grade of the tumor when compared to normal breast tissue; (C, D) represent IHC scores for Merlin and SMAD7 with respect to nodal involvement; (E, F) represent staining for Merlin and SMAD7 in relation to the occurrence of metastasis; (G, H) represent staining for Merlin and SMAD7 in relation to the disease stage. Mean Merlin and mean SMAD7 IHC scores were computed with respect to tumor grade. The mean Merlin score for normal breast tissue is significantly higher than that in tumor tissues of all grades (Dunnett’s test, P < 0.0001 for each). SMAD7 staining intensity decreases with advanced grade of the tumor tissue (normal tissue versus grades II and III: Dunnett’s test, P < 0.0001 for each). The difference in SMAD7 intensity with respect to grade I is not significant (Dunnett’s test, P = 0.0553). The staining intensity for Merlin and SMAD 7 are concordantly significantly decreased with nodal involvement (Dunnett’s test, P < 0.0001 for each). Merlin and SMAD7 levels are significantly decreased overall in breast tumor tissues (Dunnett’s test, P < 0.0001 for each) regardless of metastasis. (I) Representative immunohistochemistry images are shown for Merlin and SMAD7 staining. Panels a and c represent normal breast tissues stained for Merlin; panels b and d represent normal breast tissues stained for SMAD7; panels e and g are representative of Merlin staining seen in node negative and metastatic breast cancer tissues; panels f and h depict SMAD7 for the corresponding tissues. (J) Denotes the correlation between Merlin expression and SMAD7. A scatterplot of mean IHC scores of Merlin versus SMAD7 shows a very strong positive linear relation between them (R2 = 0.97, ANOVA P = 0.0003). The resulting least squares regression line (or line of best fit) is Mean (Merlin) = −83.15 + 20.17*Mean (SMAD7). It shows that one unit increase in Mean (SMAD7) corresponds on the average to 20.17 units increase in Mean (NF2) levels. Pearson’s correlation coefficient between mean Merlin and mean SMAD7 when analyzed with respect to tumor grade is r = 0.985.

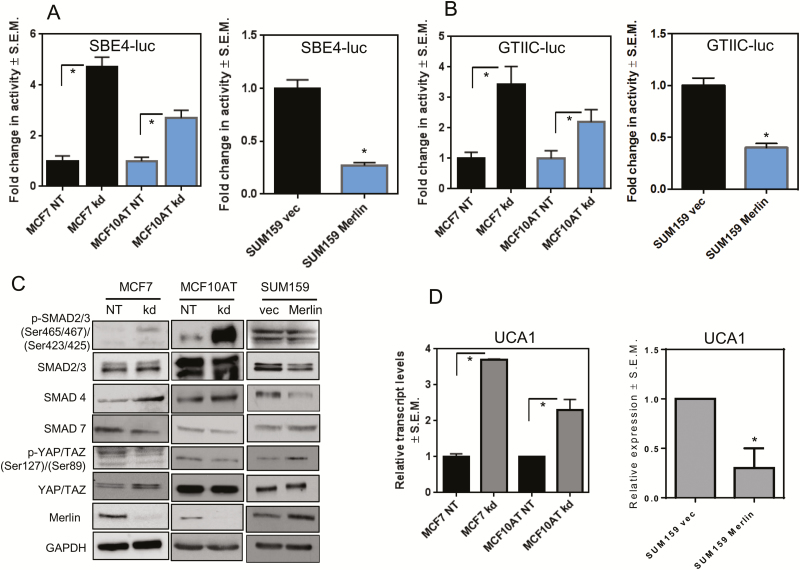

Loss of Merlin contributes to unrestrained YAP/TAZ activity and TGF-β signaling

In order to mimic the loss of Merlin seen in breast cancer progression, MCF7 and MCF10AT breast cancer cell lines were stably knocked down for NF2. With the loss of Merlin associating closely with the loss of SMAD7, we evaluated the transcriptional activity of TGF-β in cells engineered to be stably deficient for Merlin. The activity of the SMAD-dependent luciferase reporter was significantly upregulated in Merlin-deficient cells (Figure 2A). Merlin is known to activate Hippo signaling that involves phosphorylation and subsequent inhibition of YAP/TAZ co-transcriptional factors by cytoplasmic retention or degradation (18). Indeed, luciferase reporter activity assays showed that upon NF2 silencing, transcriptional activity of the Hippo pathway TEAD proteins is increased (Figure 2B). This is in agreement with decreased inhibitory phosphorylation of YAP and TAZ at Ser127 and Ser89, respectively, in Merlin-deficient cells (Figure 2C) simultaneous with an increase in regulatory and co-regulatory effectors of the TGF-β pathway. Cells knocked down for Merlin demonstrated an increase in phosphorylated SMAD2/3 and SMAD4. The inhibitory effector SMAD7 was downregulated (Figure 2C). Conversely, restoration of Merlin in SUM159, a breast cancer cell line with low Merlin expression, attenuated the activity of SMAD (Figure 2A) and TEAD (Figure 2B) luciferase reporters. This was in agreement with inhibition of TGF-β pathway-related proteins and increased inhibitory phosphorylation of the YAP and TAZ proteins (Figure 2C). These results collectively indicate that loss of Merlin contributes to unrestrained YAP/TAZ activity and TGF-β signaling.

Figure 2.

Merlin deficiency leads to the co-operative activation of YAP/TAZ/SMAD signaling. MCF7 and MCF10AT cells knocked down for NF2 (MCF7 kd and MCF10AT kd), control (MCF7 NT and MCF10AT NT), and SUM159 cells restored for Merlin expression were analyzed for (A) SMAD binding site activity by SBE4 luciferase reporter assay and (B) YAP/TAZ activity with an 8XGTIIC luciferase reporter assay. Merlin deficient cells demonstrate upregulated TGF-β signaling evidenced by increased activity of the Smad-binding element with concomitant inactive Hippo signaling as evident by increased activity of the TEAD-binding element. Merlin restoration reduced SMAD and YAP/TAZ activities. (C) Control and Merlin-deficient MCF7 and MCF10AT cells and SUM159 cells (vector control and Merlin expressing) were immunoblotted for the effectors of TGF-β signaling pathway: total SMAD2/3, phosphorylated SMAD2/3 (Ser465/467 and Ser423/425, respectively), SMAD4 and SMAD7, and for members of the Hippo pathway (total YAP/TAZ, inhibitory phosphorylated YAP and TAZ (Ser127 and Ser89, respectively)). GAPDH was used as a loading control. (D) Merlin deficient MCF7 and MCF10AT cells (kd) demonstrate significantly increased levels of UCA1. In contrast, SUM159 cells re-expressing Merlin show significantly decreased levels of UCA1. UCA1 levels were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. β-actin was used as control gene. Relative expression was measured by 2−∆∆Ct method.

The association of TGF-β-regulated SMADs with active YAP/TAZ in a transcriptional complex is reported to shift TGF-β signaling pathway’s role from functioning in a tumor suppressive role to a pro-tumorigenic role. The YAP/TAZ/SMAD transcriptional complex targets a set of genes distinct from the ones they modulate independently (19). In accordance with this, we observed that expression of three characteristic YAP/TAZ/SMAD target genes were enhanced upon loss of Merlin (Figure 2D; Supplementary Figure 1A, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Cells restored for Merlin showed the most decrease in the levels of target gene urothelial cancer associated 1 (UCA1) (Figure 2D). Treatment of cells with A8301, a TGF-β type I receptor inhibitor, caused a decrease in UCA1 expression (Supplementary Figure 1B, available at Carcinogenesis Online) confirming that UCA1 is in fact, a target of SMAD activity. Cumulatively, the results corroborate with the co-operative activity of YAP/TAZ/SMAD leading to upregulation of UCA1 upon Merlin loss. UCA1 encodes for a recently discovered long non-coding RNA that plays a role in various malignancies, including breast cancer, by modulating several genes involved in tumorigenesis, cell proliferation, migration, invasion and metabolism, particularly glycolysis (23–25). Therefore we evaluated the potential role of UCA1 as a novel mechanistic effector in the glycolytic shift of NF2-silenced breast cancer cells.

Loss of Merlin alters cancer cell metabolism and bioenergetics

UCA1 directs activation of AKT and STAT3 with consequential effects on promoting proliferation and blocking apoptosis (26,27). Accordingly, Merlin deficient cells show upregulated phospho-AKT (Ser473) and phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705) (Figure 3A) with a simultaneous increase in hexokinase 2 (HK2) expression. This is in agreement with increased transcriptional activity of STAT3 reporter (Supplementary Figure 1C, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Conversely, Merlin restoration in SUM159 cells reduced phospho-AKT and phospho-STAT3 levels concomitantly with decreased HK2 expression (Figure 3A). HK2 is a crucial enzyme that mediates the rate limiting-step of glycolysis. HK2 mediates conversion of glucose into glucose-6-phosphate, and this phosphorylation impedes glucose’s ability to leave the cell, committing it to undergo glycolysis. Thus, upregulation of HK2 is an important attribute of glycolysis.

Figure 3.

Loss of Merlin induces bioenergetics alterations in breast cancer cells. (A) Protein lysates of MCF7 and MCF10AT cells silenced for Merlin (kd) and control (NT) and SUM159 Merlin restored and vector control cells were immunoblotted for STAT3, phosphorylated STAT3 (Tyr705), total AKT (pan-AKT), phosphorylated AKT (Ser473) and HK2. Cell-free culture media of MCF7 and MCF10AT cells knocked down for NF2 (MCF7 kd and MCF10AT kd, respectively), their control (MCF7 NT and MCF10AT NT, respectively) and SUM159 cells (vector control and Merlin-reexpressing) was assayed for (B) glucose consumption (C) and lactate production. Values were normalized to total protein. (D) Cells depleted for Merlin displayed an increased ECAR indicating increased glycolysis in the cells. SUM159 cells restored for Merlin expression demonstrated decreased ECAR. (E) Merlin deficient cells demonstrated decreased OCR and increased glycolysis, in contrast to SUM159 cells restored for Merlin expression.

Given the increased levels of HK2 in Merlin-silenced cells, we evaluated the impact of Merlin deficiency on breast tumor cell metabolism. Loss of Merlin increased glucose uptake and lactate export in both MCF7 and MCF10AT cell lines (Figure 3B and C). Conversely, SUM159 cells re-expressing Merlin showed reduced glucose consumption and lactate production. Merlin-deficient cells also presented greater ECAR consistent with increased glycolysis (Figure 3D). Oxygen consumption rate was decreased in Merlin-deficient cells compared to control cells (Figure 3E). This phenotype was reversed in cells restored for Merlin expression characterized by a decrease in ECAR and an increase in OCR (Figure 3D and E).

We analyzed the levels of metabolites of the TCA pathway using a targeted metabolomics approach. SUM159 cells re-expressing Merlin showed a collective increase in cellular abundance of TCA metabolites (Figure 4A). In contrast, knocking down Merlin in MCF10AT cells caused a decrease in cellular levels of TCA metabolites. Concomitant with these metabolic changes, loss of Merlin in MCF10AT and in MCF7 cells caused an increase in transcript levels of glucose transporters 3 and 4 (GLUT3 and GLUT4) (Figure 4B). This is consistent with increased glucose consumption (Figure 3B) and increased levels of glucose-6-phosphate (Supplementary Figure 2A, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The levels of monocarboxylate transporters (MCT 1, 2, 3), that transport lactate to the extracellular media, were also elevated in cells deficient for Merlin when compared with their controls (Figure 4C). Merlin deficiency resulted in increased levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDHA and LDHB), enzymes that channel the final step in glycolysis by converting pyruvate into lactate (Figure 4D). Conversely, in SUM159 cells restored for Merlin the levels of glucose and lactate transporters were decreased with simultaneous decreases in LDHA and LDHB (Figure 4B and D). Collectively these data indicate that Merlin keeps a check on components of glucose consumption and glycolysis mediators, and the loss of Merlin induces metabolic and bioenergetics adaptations in breast cancer cells.

Figure 4.

Merlin keeps a check on cellular metabolism and glycolysis mediators. (A) The lysates of MCF10AT cells knocked down for Merlin (kd) and the respective control (NT) and SUM159 cells (vector only and restored for Merlin) were analyzed by a targeted metabolomics assessment for the levels of the indicated metabolites of the TCA cycle. Restoration of Merlin increases the total cellular levels of TCA intermediates while Merlin deficiency has the opposite effect. The steady-state transcript levels of glucose transporters (GLUT) (B), monocarboxylate transporters transporters (MCT) (C) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDHA and LDHB) (D) were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR from MCF10AT and MCF7 cells (NT and kd) and SUM159 cells restored for Merlin (SUM159 Merlin) and their respective vector control (SUM159 vec). β-actin was used as control gene. *P < 0.05 relative to their indicated respective controls.

UCA1 directs cell metabolism towards aerobic glycolysis through AKT and STAT3 activation in Merlin-deficient cells

We hypothesized that upregulation of UCA1 was vital to the metabolic adaptations observed in Merlin-deficient cells. In order to address this, we silenced UCA1 in Merlin-deficient MCF7 cells. UCA1 silencing resulted in decreased phosphorylation of both, AKT and STAT3 (Figure 5A; Supplementary Figure 2B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Importantly, HK2 expression was also reduced (Figure 5A). These findings suggest that loss of Merlin modulates cell metabolism towards aerobic glycolysis by invoking the participation of UCA1, AKT and STAT3.

Figure 5.

UCA1 directs cell metabolism towards aerobic glycolysis through AKT and STAT3 activation in Merlin-deficient cells. (A) Immunoblotting of protein lysates of Merlin-deficient MCF7 cells silenced for UCA1 (siUCA1) and non-target control (NTC) showed reduced level of phosphorylated AKT (Ser473), phosphorylated STAT3 (Tyr705) and HK2 upon UCA1 silencing. HSP90 was used a loading control. The levels of glucose uptake (B) and lactate export (C) were decreased and the overall amounts of metabolites of the TCA cycle were increased (D) as a result of blunted UCA1 expression. (E) Protein lysates of NF2-deficient MCF7 cells treated with 2 µM of STATTIC inhibitor or DMSO (vehicle control) for 48h were collected. The expression of phosphorylated STAT3 (Tyr705) and HK2 were attenuated upon STAT3 activity inhibition; β-actin was used as a loading control. The levels of glucose consumption (F) and lactate production (G) were also reduced following STATTIC treatment. (H) There was an overall increase in the amounts of metabolites of the TCA cycle in STATTIC treated MCF7 cells deficient for Merlin. *P < 0.05.

With HK2 playing an important role in the glycolytic process, we queried the effects of UCA1 and STAT3 in regulating HK2 when Merlin expression is deficient. Merlin-deficient MCF7 cells silenced for UCA1 showed a decrease in glucose consumption and lactate production relative to non-targeting control-transfected cells (Figure 5B and C). Further, Merlin-deficient cells silenced for UCA1 demonstrated a recovery in the cellular levels of TCA metabolites (Figure 5D), indicating a shift in cellular metabolism. In order to position a role for AKT and STAT3 activation leading to HK2 upregulation, we treated Merlin-deficient MCF7 cells with MK2206 and STATTIC, small molecule inhibitors of AKT and STAT3 phosphorylation, respectively. Both, MK2206 and STATTIC reduced HK2 expression relative to respective vehicle control (Figure 5E; Supplementary Figure 2C, available at Carcinogenesis Online), supporting AKT and STAT3 as upstream effectors of HK2 upregulation. Importantly, STATTIC attenuated glucose consumption and lactate production in Merlin-deficient MCF7 cells (Figure 5F and G) and recovered the cellular levels of TCA metabolites (Figure 5H). These outcomes support that the loss of Merlin induces aerobic glycolysis in breast cancer cells through the combined activities of Hippo-TGF-β signaling that impinge on the shift in cellular metabolism.

STAT3 inhibition preferentially impacts Merlin-deficient cells

Given the profound effects of STAT3 inhibition on re-aligning the metabolism of Merlin-deficient cells, we hypothesized that STAT3 signaling is essential for sustenance and/or malignant attributes of Merlin-deficient cells. We addressed this by evaluating the effect of the STAT3 inhibitor, STATTIC, on 3D cell growth. Merlin-deficient cells form characteristically invasive structures compared to Merlin-expressing MCF7 cells that give rise to well-defined spherical structures. STATTIC not only restored the circularity of the MCF7 kd structures but also seemed to limit their growth, suggesting a greater sensitivity of the Merlin-deficient cells to STAT3 inhibition (Figure 6A). When assayed for transwell invasion the MCF7 kd cells are significantly more invasive than their respective controls. While STATTIC caused a notable decrease in invasiveness of both cells, the effect on Merlin-deficient cells was strikingly greater (Figure 6B). Furthermore, a colony formation assay revealed increased sensitivity of the Merlin-deficient cells to STAT3 inhibition. The level of cell killing was notably greater in the cells knocked down for Merlin (kd) relative to the control cells, indicating that STAT3 signaling is vital for cells with Merlin deficiency (Figure 6C). Collectively, the data suggest that the loss of Merlin directs cancer cell metabolism towards aerobic glycolysis that is critically impacted by STAT3.

Figure 6.

STAT3 inhibition preferentially impacts Merlin-deficient cells. (A) Merlin-deficient cells develop an invasive 3D morphology. The STAT3 inhibitor, STATTIC, appears to not only restore circularity to this structure but also limits its growth. (B) STATTIC inhibits invasive potential of Merlin-deficient MCF7 cells through the modified Boyden chamber. (C) The ability of anchorage-independent growth was assessed by soft agar colony assay and, in a dose-dependent effect, STAT3 inhibition diminished colony formation, being more effective in NF2-silenced cells (kd). *P < 0.05. (D) Deficiency in Merlin expression results in the degradation of SMAD7, which uncouples its inhibitory modulation on the TGF-β signaling pathway. The resulting collaborative activity of TGF-β and Hippo effectors upregulates HK2 expression that dictates a metabolic preference towards aerobic glycolysis.

Discussion

Merlin has thus far been demonstrated to be at the nexus of critical developmental signaling events. This is evident in the fact that Merlin-knockout mice are embryonically lethal (11). Inactivation of the Hippo signaling pathway is one of the well-characterized consequences of Merlin loss. The Hippo signaling pathway is activated by Merlin through either modulating adherens junctions at the cell membrane or by inactivating the activity of CRL4DCAF1 ubiquitin ligase complex in the nucleus (28). Loss of Merlin abolishes the activity of Hippo, leading to dysregulated activation of transcription co-effectors YAP/TAZ, and consequently deregulated proliferation and organ size control (4,29).

In this study, we demonstrate a direct correlation between the loss of Merlin and concordant loss of SMAD7 in advanced breast cancer tissues. SMAD7 is an inhibitory SMAD of the TGF-β signaling pathway. SMAD7 exerts its negative effect by either competing with r-SMADs for binding to the type I receptor, by recruiting the SMAD specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (SMURF) to mark TGF-β receptor for degradation, or by binding to SMAD-binding elements in the DNA, compromising the r-SMADS/co-SMADs complex transcriptional activity (30,31). While Merlin and SMAD7 were robustly expressed in normal breast tissue, the two molecules appeared to have distinct cellular presence. While Merlin had an overall cellular presence, SMAD7 expression was predominantly nuclear, consistent with its role in inhibiting cell proliferation (22). The loss of Merlin in tumor tissues is in agreement with our previous study that reported the first role for Merlin in breast cancer (8). In the present study we did not register a change in the transcript levels of SMAD7 (data not shown). Thus, the loss of SMAD7 is likely due to its post-transcriptional or post-translational regulation. The stability of SMAD7 is closely regulated by SMURF proteins, in particular SMURF1 and 2 that function as E3 ubiquitin ligases (32,33). Post-transcriptionally, mir-182, upregulated by TGF-β signaling, targets SMAD7 for translational inhibition and disengages the negative feedback chain of TGF-β during metastasis (31). The regulation of SMAD7 by the mir-106b-25 microRNA cluster induces a Six1-dependent epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and a tumor initiating cell phenotype in breast cancer cells (34). It is likely that Merlin regulates SMAD7 through one or multiple of these mechanisms. Interestingly, TGF-β signaling has a tumor suppressor function in early cancer stage. However, as disease progresses, TGF-β activity is coopted to support tumor progression and metastasis (35). Therefore, TGF-β signaling inhibition has been a common therapeutic target in cancer. Although not in clinical trial, A8301 is a potent small molecule inhibitor of TGF-β type I receptor ALK5 kinase, type I activin/nodal receptor ALK4 and type I nodal receptor ALK7. A8301 has been shown to inhibit epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), a crucial step of metastasis (36).

The loss of SMAD7 in Merlin-deficient breast cancer cells enabled co-operative action of Hippo transcription co-factors and TGF-β transcription factors, YAP/TAZ/SMAD2/3, which was evident by the upregulation of signature transcriptional targets of this co-operative activity. One of the prominently upregulated targets was UCA1, an oncogenic long non-coding RNA first discovered in human bladder cancer tissue and considered a biomarker (37). Functionally, UCA1 activates PI3K-AKT signaling and potentiates bladder cancer progression (38). Unrestrained activation of AKT signaling pathway results in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and chemo-radiation resistance. A promising strategy to target AKT signaling is by the administration of the MK-2206 allosteric inhibitor that prevents phosphorylation of the T308 and S473 sites required for full AKT activation. MK-2206 has advanced to phase I and phase II clinical trials as a monotherapy or in combination with other commonly used chemotherapeutics showing tolerable side effects (39). The oncogenic role of UCA1 has been further described in many other malignancies including breast, colorectal and hepatocellular carcinoma (23). While the mechanistic association between UCA1 and cancer metabolism is still poorly characterized, UCA1 has been demonstrated to induce aerobic glycolysis (38).

Hexokinase 2 (HK2) is an enzyme bound to the outer mitochondrial membrane by the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC). VDAC enables transport of ATP generated in mitochondria to associate with HK2 inducing phosphorylation of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate (40). HK2 stimulates glucose flux into cancer cells resulting in a glucose gradient (41). Increased HK2 activity in cancer cells is accompanied by upregulation of glucose transporters (GLUTs), conversion of pyruvate to lactate mediated by lactate dehydrogenase enzymes (LDH) and transport of excessive intracellular lactate to the extracellular microenvironment through monocarboxylate transporters (MCT). Thus, upregulation of UCA1 leading to increased HK2 levels represents an important mechanism that enables Merlin deficient tumor cells to maintain their metabolic requirements. Merlin-deficient cells registered activated phospho-STAT3 as an outcome of upregulated UCA1. Several target genes of STAT3 include proteins that are involved in cell survival and proliferation. Although its pleiotropic nature was reported across multiple studies, STAT3 is generally considered a growth-promoting anti-apoptotic factor. STAT3 activation in both, tumors and immune cells, contributes to several malignant phenotypes of human cancers and to compromised anticancer immunity, cumulatively leading to poor clinical outcomes (42,43). STAT3 overexpression is significantly linked to poor prognosis in breast cancer, NSCLC (adenocarcinoma) and gastric cancers (44). STAT3 has prominent impacts on glycolytic functions, partly mediated by c-myc, that upregulate glycolysis genes such as GLUT-1, HK2, ENO-1 and PFKM (45,46). STAT3 directly activates transcription of HK2 and enhances glycolysis in breast cancer cells (47). Our data corroborates with this finding and further demonstrates a critical role for STAT3 in impacting glycolysis in breast cancer cells that have decreased Merlin expression. We also have observed that STAT3 inhibition in Merlin-deficient cells alters cellular metabolism to reduce glycolysis and pivots cells towards enhanced utilization of the TCA pathway with a concomitant decrease in their invasive attributes. Merlin deficiency engenders cellular dependence on STAT3 signaling, endorsing a critical role for STAT3-mediated metabolic adaptation in sustaining these cells (Figure 6D). The STAT3 signaling pathway has different sites that may be intervened in order to inhibit its activity, such as the SH2, DNA binding and N-terminal domains (48). Disruption of STAT3 signaling increases apoptosis. As such, application of STAT3 inhibitors represents a promising cancer therapeutic strategy. While STAT3 inhibitors show high selectivity for STAT3-addicted tumor cells compared to healthy cells, unexpected toxicity is observed in clinical trials (49). As such, patient stratification would ideally obviate some of the unnecessary side-effects in those who may not benefit from this treatment. Our findings can help identify a patient population of Merlin and SMAD7-deficient breast tumors that may benefit from treatment with STAT3 inhibitors.

The reset of cancer cells’ metabolism is one of the prominent hallmarks of malignancy once the neoplastic cells identify the need to acquire extra energy to sustain their proliferative and maintenance processes (50). This is characterized by an increase in glucose consumption and aerobic glycolysis and by profound bioenergetics adaptations in the cancer cells. Our data provides evidence that loss of Merlin engages the cell to employ co-operative signaling activities of the Hippo and TGF-β pathways that enable alterations in cellular metabolism and bioenergetics.

Supplementary material

Supplementary materials can be found at Carcinogenesis online.

Funding

National Cancer Institute (R01CA138850, R01CA169202 to L.A.S.); Department of Defense (W81XWH-14-1-0516 and W81XWH-18-1-0036 to L.A.S.); The George and Ameilia G Tapper Foundation; Breast Cancer Research Foundation of Alabama (to L.A.S.); NCI R01CA194048 and BX003374 to R.S.S.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We also would like to acknowledge the UAB Targeted Metabolomics and Proteomics Laboratory for their expertise in metabolomics analyses.

Authors’ contributions: WPJ, MM, RSS and LAS designed the study and the approaches. WPJ, MM, JWR, PV, AL and SKB acquired the data. WPJ, MM, MSM, RSS, PV, AL and LAS analyzed and interpreted the results. MM, PV and LAS wrote the manuscript.

Consent for publication: All authors have read and agreed with the final paper. The information in this manuscript has been agreed for submission by all authors and we confirm that this work has not been published or submitted for publication elsewhere.

Competing interests/conflict of interest: We declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval: The immunohistochemistry study was granted an exemption from requiring ethics approval from the institutional review board at the University of South Alabama.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AKT

protein kinase B

- CRL4DCAF1

Cullin-ring ligase 4. DNA damage-binding protein 1 and cul4-associated factor 1

- ECAR

extracellular acidification rate

- FERM

four-point-one, ezrin, radixin, moesin

- HK2

hexokinase 2

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- MCT

monocarboxylate transporter

- mir

microRNA

- NF2

neurofibromin 2

- OCR

oxygen consumption rate

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- SMURF

SMAD specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TAZ

transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- TEAD

TEA domain transcription factor

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor β

- UCA1

urothelial cancer associated 1

- YAP

Yes-associated protein

References

- 1. Kalyanaraman B. (2017)Teaching the basics of cancer metabolism: developing antitumor strategies by exploiting the differences between normal and cancer cell metabolism. Redox Biol., 12, 833–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mishra P., et al. (2015)Metabolic signatures of human breast cancer. Mol. Cell. Oncol., 2, e992217-1–e992217-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson N.M., et al. (2018)The emerging role and targetability of the TCA cycle in cancer metabolism. Protein Cell, 9, 216–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petrilli A.M., et al. (2016)Role of Merlin/NF2 inactivation in tumor biology. Oncogene, 35, 537–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xiao G.H., et al. (2005)The NF2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, inhibits cell proliferation and cell cycle progression by repressing cyclin D1 expression. Mol. Cell. Biol., 25, 2384–2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thurneysen C., et al. (2009)Functional inactivation of NF2/merlin in human mesothelioma. Lung Cancer, 64, 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murray L.B., et al. (2012)Merlin is a negative regulator of human melanoma growth. PLoS One, 7, e43295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morrow K.A., et al. (2011)Loss of tumor suppressor Merlin in advanced breast cancer is due to post-translational regulation. J. Biol. Chem., 286, 40376–40385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morrow K.A., et al. (2016)Loss of tumor suppressor Merlin results in aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancer. Oncotarget, 7, 17991–18005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Das S., et al. (2017)Loss of Merlin induces metabolomic adaptation that engages dependence on Hedgehog signaling. Sci. Rep., 7, 40773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McClatchey A.I., et al. (1997)The Nf2 tumor suppressor gene product is essential for extraembryonic development immediately prior to gastrulation. Genes Dev., 11, 1253–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McClatchey A.I., et al. (1998)Mice heterozygous for a mutation at the Nf2 tumor suppressor locus develop a range of highly metastatic tumors. Genes Dev., 12, 1121–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Giovannini M., et al. (2000)Conditional biallelic Nf2 mutation in the mouse promotes manifestations of human neurofibromatosis type 2. Genes Dev., 14, 1617–1630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gladden A.B., et al. (2010)The NF2 tumor suppressor, Merlin, regulates epidermal development through the establishment of a junctional polarity complex. Dev. Cell, 19, 727–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang N., et al. (2010)The Merlin/NF2 tumor suppressor functions through the YAP oncoprotein to regulate tissue homeostasis in mammals. Dev. Cell, 19, 27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Larsson J., et al. (2008)Nf2/merlin regulates hematopoietic stem cell behavior by altering microenvironmental architecture. Cell Stem Cell, 3, 221–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morris Z.S., et al. (2009)Aberrant epithelial morphology and persistent epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in a mouse model of renal carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 106, 9767–9772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Piccolo S., et al. (2014)The biology of YAP/TAZ: hippo signaling and beyond. Physiol. Rev., 94, 1287–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hiemer S.E., et al. (2014)The transcriptional regulators TAZ and YAP direct transforming growth factor β-induced tumorigenic phenotypes in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem., 289, 13461–13474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Redmann M., et al. (2018)Methods for assessing mitochondrial quality control mechanisms and cellular consequences in cell culture. Redox Biol., 17, 59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ross K.L., et al. (2009)Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry of glycolytic intermediates: deconvolution of coeluting structural isomers based on unique product ion ratios. Anal. Chem., 81, 4021–4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Emori T., et al. (2012)Nuclear Smad7 overexpressed in mesenchymal cells acts as a transcriptional corepressor by interacting with HDAC-1 and E2F to regulate cell cycle. Biol. Open, 1, 247–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xue M., et al. (2016)Urothelial cancer associated 1: a long noncoding RNA with a crucial role in cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol., 142, 1407–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li H.J., et al. (2015)Long non-coding RNA UCA1 promotes glutamine metabolism by targeting miR-16 in human bladder cancer. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol., 45, 1055–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zuo Z.K., et al. (2017)TGFβ1-Induced LncRNA UCA1 upregulation promotes gastric cancer invasion and migration. DNA Cell Biol., 36, 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang C., et al. (2012)Long non-coding RNA UCA1 regulated cell cycle distribution via CREB through PI3-K dependent pathway in bladder carcinoma cells. Gene, 496, 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu W., et al. (2013)Ets-2 regulates cell apoptosis via the Akt pathway, through the regulation of urothelial cancer associated 1, a long non-coding RNA, in bladder cancer cells. PLoS One, 8, e73920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li W., et al. (2012)Merlin: a tumour suppressor with functions at the cell cortex and in the nucleus. EMBO Rep., 13, 204–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Serrano I., et al. (2013)Inactivation of the Hippo tumour suppressor pathway by integrin-linked kinase. Nat. Commun., 4, 2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stolfi C., et al. (2013)The dual role of Smad7 in the control of cancer growth and metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 14, 23774–23790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu J., et al. (2016)MicroRNA-182 targets SMAD7 to potentiate TGFβ-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of cancer cells. Nat. Commun., 7, 13884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grönroos E., et al. (2002)Control of Smad7 stability by competition between acetylation and ubiquitination. Mol. Cell, 10, 483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fukasawa H., et al. (2004)Down-regulation of Smad7 expression by ubiquitin-dependent degradation contributes to renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 101, 8687–8692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith A.L., et al. (2012)The miR-106b-25 cluster targets Smad7, activates TGF-β signaling, and induces EMT and tumor initiating cell characteristics downstream of Six1 in human breast cancer. Oncogene, 31, 5162–5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Massagué J. (2008)TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell, 134, 215–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tojo M., et al. (2005)The ALK-5 inhibitor A-83-01 inhibits Smad signaling and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by transforming growth factor-beta. Cancer Sci., 96, 791–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang X.S., et al. (2006)Rapid identification of UCA1 as a very sensitive and specific unique marker for human bladder carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res., 12, 4851–4858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li Z., et al. (2014)Long non-coding RNA UCA1 promotes glycolysis by upregulating hexokinase 2 through the mTOR-STAT3/microRNA143 pathway. Cancer Sci., 105, 951–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nitulescu G.M., et al. (2016)Akt inhibitors in cancer treatment: the long journey from drug discovery to clinical use (Review). Int. J. Oncol., 48, 869–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mathupala S.P., et al. (2006)Hexokinase II: cancer’s double-edged sword acting as both facilitator and gatekeeper of malignancy when bound to mitochondria. Oncogene, 25, 4777–4786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Patra K.C., et al. (2013)Hexokinase 2 is required for tumor initiation and maintenance and its systemic deletion is therapeutic in mouse models of cancer. Cancer Cell, 24, 213–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Carpenter R.L., et al. (2014)STAT3 target genes relevant to human cancers. Cancers (Basel)., 6, 897–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aleskandarany M.A., et al. (2016)The prognostic significance of STAT3 in invasive breast cancer: analysis of protein and mRNA expressions in large cohorts. Breast Cancer Res. Treat., 156, 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chiba T. (2016)STAT3 inhibitors for cancer therapy-the rationale and remained problems. EC cancer, 1, S1. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Poli V., et al. (2015)STAT3-mediated metabolic reprograming in cellular transformation and implications for drug resistance. Front. Oncol., 5, 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. San-Millán I., et al. (2017)Reexamining cancer metabolism: lactate production for carcinogenesis could be the purpose and explanation of the Warburg Effect. Carcinogenesis, 38, 119–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jiang S., et al. (2012)A novel miR-155/miR-143 cascade controls glycolysis by regulating hexokinase 2 in breast cancer cells. EMBO J., 31, 1985–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yue P., et al. (2009)Targeting STAT3 in cancer: how successful are we?Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs, 18, 45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wong A.L.A., et al. (2017)Do STAT3 inhibitors have potential in the future for cancer therapy?Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs, 26, 883–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hanahan D., et al. (2011)Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell, 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.