Abstract

BACKGROUND

The roots of advanced practice nursing (APN) can be traced back to the 1890s, but the nurse practitioner (NP) emerged in Western countries during the 1960s in response to the unmet healthcare needs of populations in rural areas. These early NPs utilized the medical model of care to assess, diagnose and treat. Nursing has since grown as a profession, with its own unique and distinguishable, holistic, science-based knowledge, which is complementary within the multidisciplinary team. Today, APNs demonstrate nursing expertise in clinical practice, education, research and leadership, and are no longer perceived as “physician replacements” or assistants. Saudi Arabia has yet to define, legislate or regulate APN.

AIMS

This article aims to disseminate information from a Saudi APN thought leadership meeting, to chronicle the history of APN within Saudi Arabia, while identifying strategies for moving forward.

CONCLUSION

It is important to build an APN model based on Saudi healthcare culture and patient population needs, while recognizing global historical underpinnings. Ensuring that nursing continues to distinguish itself from other healthcare professions, while securing a seat at the multidisciplinary healthcare table will be instrumental in advancing the practice of nursing.

Today, advanced nursing practice (APN) is evident in both developed and developing countries. The World Health Organisation (WHO) supports its growth in order to meet growing global healthcare needs.1 In 1999 the United Kingdom (UK) government called for senior clinical nurses to be partnered as equals with senior medical providers. Nurse consultants (NC) were appointed to the top of the clinical-academic ladder, keeping experienced nurse specialists in clinical practice to advance the research agenda and facilitate collaboration on service development.2,3 In 2010 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the US called for nurses to be allowed to practice to the full extent of their education and to be partners with physicians in redesigning healthcare.4 While it is not the intention of this article to review the history of APN in countries outside of Saudi Arabia, a brief overview is necessary to contextualise how and why APN roles have emerged and their impact on healthcare provision internationally.

The International Council of Nurses (ICN) defines Advanced Practice Nursing thus:

“A Nurse Practitioner/Advanced Practice Nurse is a registered nurse who has acquired the expert knowledge base, complex decision-making skills and clinical competencies for expanded practice, the characteristics of which are shaped by the context and/or country in which s/he is credentialed to practice. A master’s degree is recommended for entry level.”5

Globally APN shares some common features, alongside aspects that are unique to the needs of the country and the authority of bodies that regulate nursing.6 Although there is evidence that English-trained nurses worked as APNs as early as the 1890s in Canadian outpost areas, the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) was the first to be formally recognized in the 1950s. CNSs responded to the needs of patients with chronic and complex conditions. NP roles developed later in the 1960s, primarily in response to unmet healthcare needs particularly in rural areas where primary care physicians were lacking.7–12 Although advanced practice started with specialist nurses, the modern day APN is commonly recognized as the nurse practitioner (NP). Brooke and Rushforth (2011) describe the NP role as hybrid in nature, involving autonomous medical diagnosis. This may indicate why many countries are more concerned with its regulation.13 North American nursing bodies strictly regulate APN via protected titles and post-masters level education board certification. The umbrella of advance practice includes the CNS, NP, certified nurse anesthetist (CRNA) and certified nurse-midwife (CNM).12 The NP role in the UK is similar to that of North America, but the role of the AP specialty nurse is where improved outcomes have been demonstrated. Specialist practice denotes a specific area of practice and advanced practice a level of practice; both generalists and specialists may practice at an advanced level.14,15 NC, at the top of the clinical ladder, are responsible for service development and setting research and education agendas; a doctorate is desirable.3 While studying AP roles in the UK, US, Brazil and Thailand, Ketefian et al (2001) identified three common drivers for APN; the professionalization of nursing, its need to be autonomous and its role in meeting the country’s health needs. They also recognized how each country had developed roles differently and with different levels of post basic education.16

Nursing in Saudi Arabia

The education of nurses in Saudi Arabia commenced in 1954, but nursing is not the preferred career choice, particularly for females due to cultural reasons and family challenges. The requirement to work night shifts and the poor image of nursing within the community compound these challenges.17 Consequently the government is forced to increasingly depend on expatriates due to the rapid expansion of the Saudi Healthcare System.18 According to the WHO (2015) the nursing ratio to population in Saudi Arabia was 48.7 to 10 000, compared to Oman 53.8, the UK 88, Canada 92.9, Australia 106.5, Japan 114.9 and Qatar 118.7.19 In an attempt to combat this, a number of universities now offer bachelors of science in nursing for males and females, while the masters of science in nursing is offered presently for females only. Furthermore, international scholarships have been made available by governmental organizations to enable nurses to achieve nursing qualifications at all levels;18 including clinical masters such as APN. Despite anecdotal information that Saudi nurses have studied APN at international universities, there is little information available on their career progression once they return to Saudi Arabia. Without standardization of a formal clinical career ladder along with titles and job descriptions reflecting role and scope of practice, these nurses will remain difficult to differentiate from other RNs and will not fulfill the role for which they have been educated.

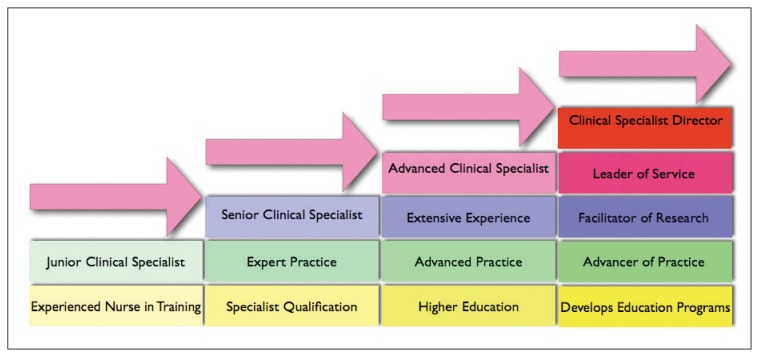

The Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS) designates nursing in line with level of education only; these designations are presently not aligned with job description titles, experience, roles or scopes of practice. According to the SCFHS the first level of nursing, defined as diploma level, is currently classified as “technical nursing”; this also applies to RNs with higher degrees in other health sciences. Nurses with a baccalaureate degree in nursing are designated as “specialists”, despite not necessarily having specialty experience, certification, or a higher level of education. Nurses with a masters degree in nursing are classified as “Specialist 1”, while nurses with a PhD and three years of experience are classified as “nurse consultant.”20 It will be important moving forward to differentiate clinical ladders from those of academia and leadership. The only evidence of implementation of a clinical ladder has been published previously21 (Figure 1), but it has not been driven by the Ministry of Health (MOH) and so is not recognized within the official grading structure. This lack of recognition deters senior nurses from staying in clinical practice, making it difficult to meet the nation’s growing healthcare needs.

Figure 1.

From Hibbert D, AlSanea N, Balens B. (2012) Perspectives on specialist nursing in Saudi Arabia: A national model for success. Ann Saudi Med; 32(1): 78–85.

The Saudi healthcare system is challenged by inadequate primary care provision, with insufficient general practitioners. Consequently, patients often resort to visiting the emergency room for non-emergent acute and chronic healthcare needs. As the Saudi population ages and the incidence and prevalence of chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension increase, the shortage of primary care providers is likely to have a significant negative impact on the Saudi healthcare system and its clients. Likewise there are a limited number of nurses qualified to care for patients with chronic conditions in specialty areas; these nurses are hampered in nurse-led clinics by a lack of autonomy to assess, diagnose and prescribe. Driven by increasing population needs nursing is advancing, but without recognition, definition, legislation or a regulatory framework.21,22

Advancing the Practice of Nursing in Saudi Arabia

Globally APNs have spent decades trying to ensure that others can distinguish their role from that of physician, but have not always been successful.23 Now is an optimal time to define APN in Saudi Arabia, in a culturally appropriate way that utilises nursing as an effective resource for the health of its citizens. This requires legislation, the provision of higher education aimed at advanced practice, protection of titles and regulation of the scope of practice; ensuring knowledgeable experts are caring for patients safely and effectively while delivering patient centered care based on the latest evidence.

Chronicling the APN Story

In telling the APN story in Saudi Arabia (Table 1) the authors admit a bias towards events at KFSHRC. Verbal communication from contacts at several larger hospitals suggests that there is wide support within the nursing community for APN. On the 17 March 2015 the first Saudi APN thought leadership event was held at the Four Seasons Hotel, Riyadh, sponsored by the Saudi Enterostomal Therapy Chapter of the Saudi Society of Colon and Rectal Surgery and hosted by Ms. Kathy Sienko, the then Deputy Executive Director for Nursing Affairs at KFSHRC. Nurse leaders and physicians from KFRSHRC along with invited keynote speakers from the USA, UK and Saudi Arabia opened a dialogue aimed at facilitating discussion and debate. At this first thought leadership event in March 2015, a physician leader highlighted the need for wider engagement beyond the group of nursing and physician “believers” who had convened. Hence on the 13 October 2015 the inaugural Saudi Advancing Nursing Practice Thought Leadership Event was held, the aim being to gather the collective experience and wisdom of national and international experts including APNs, nursing executives, academics, physician leaders and members of the SCFHS to inform a discussion on how nursing practice might be advanced in Saudi Arabia.

Table 1.

The history of advanced practice nursing in Saudi Arabia.

| Date | Event | Progression |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1980s | KFSHRC Job Descriptions for Specialty Practice | Stoma, Wound, Continence, Pain, Infection Control, Palliative Care |

| 1990s | KFSHRC APN Job Description | Developed without a nursing credentialing or privileging framework. |

| 1990s | KFSHRC Policy on Non-Physician Prescribing | For Pharmacists and Nurses |

| Mar 2008 | KFSHRC Clinical Ladder | Aimed at growing nurses in specialty practice from novice to expert, including APN and NC (Figure 2)20 |

| Jun 2010 | Recognition by the SCFHS of the Enterostomal Therapy Diploma Program | A 12-month full time program, incorporating both theoretical and clinical components, aimed at developing Saudi Nurses to care autonomously for patients with stomas, incontinence, defecatory dysfunction, and wounds, including nurse-led clinics5,20 |

| Oct 2011 | KFSHRC tasked APN proposal | Both general and specialty APN pathways were proposed, along with nursing credentialing and privileging. |

| Jun 2012 | Publication: Specialist Nursing in Saudi Arabia | Perspectives on specialist nursing in Saudi Arabia: A national model for success20 |

| Jan 2013 | KFSHRC Nurse Credentialing & Privileging Committee | Nurse credentialing and privileging committee established. |

| Jan 2013 | SCFHS Dialogue | Started dialogue with SCFHS |

| Jan 2014 | Invited publication: ICN/APN Education Committee | Addressing issues impacting advanced nursing practice worldwide |

| Jan 2015 | Invited publications: series based on the provision of specialty nursing services | 1. Developing enterostomal therapy as a nursing specialty in Saudi Arabia: which model fits best?21 2. The development of nurse-led bowel dysfunction clinics in Saudi Arabia: against all odds22 |

| Mar 2015 | 1st APN Thought Leadership Event Riyadh | KFSHRC nurse and physician leaders and APNs, aimed at opening a local dialogue |

| Oct 2015 | 1st Nursing Symposium aimed at APN in Saudi Arabia | KFSHRC Riyadh Biennial Nursing Symposium main theme APN. Nurses from Saudi Arabia, the Gulf and invited international experts shared their experiences. |

| Oct 2015 | 1st Inaugural Saudi APN leadership meeting | Aimed at starting a national APN dialogue |

| Oct 2015 | Chair, SCFHS, Nursing Scientific Committee, announces support from SCFHS | Dr. Ahmad Aboshaiqah (Chair, Nursing Scientific Committee, SCFHS) announced his and the SCFHS support for discussion and planning for APN in Saudi Arabia, in particular the community NP role |

| Jan 2016 | First two KFSHRC Saudi Nurse’s appointed as APNs | Ms. Hajer AlSabaa and Ms. Haifaa Hussain returned from scholarships in the USA after gaining their APN Masters degree, employed in APN positions (Colorectal and Paediatric populations) |

| Sept 2016 | ICN/APN Hong Kong podium presentations include Saudi Arabian perspective | 1. An international forum to share innovation strategies and creative modalities in advanced practice. Beachesne, M., Scanlon, A., Carryer, J., Debout, C., East, L.A., Hibbert, d., Honig, J. 2. A survey of clinical education of APN: a global perspective. Beachesne, M., Scanlon, A., Carryer, J., Debout, C., East, L.A., Hibbert, D., Honig, J. |

Inaugural National APN Thought Leadership Event

This inaugural event was sponsored by Ms. Rosemarie Paradis, Executive Director of Nursing Affairs and led by Ms. Kathy Sienko, along with Ms. Denise Hibbert and Ms. Debra Forestell. The intent was not to discuss titles or roles but to focus on the enablers and obstacles to APN that may be experienced in any geography, while positioning the discussion within the context of KFSHRC and Saudi Arabia.

The goals and objectives of the event were to discuss the rationale, benefits and obstacles for introducing APN in both general and specialist organizations, engage stakeholders in the APN discussion, discuss cultural issues associated with the APN role, explore what it means to be an AP at the bedside, explore and achieve consensus on different types of roles under the APN banner, identify the organizational infrastructure required to support such roles, consider the legal and professional implications for Saudi Arabia, and understand the educational and board certification application to the Saudi context.

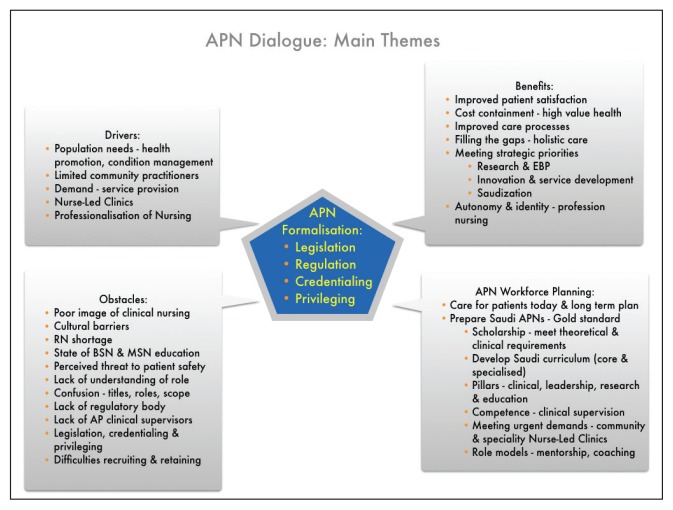

APN Dialogue

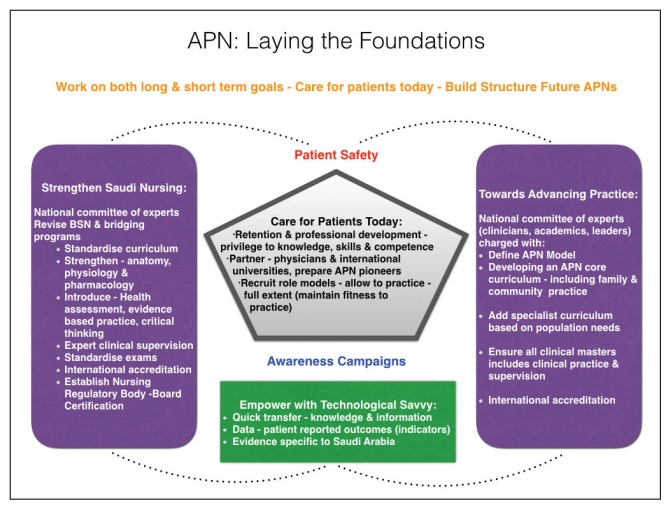

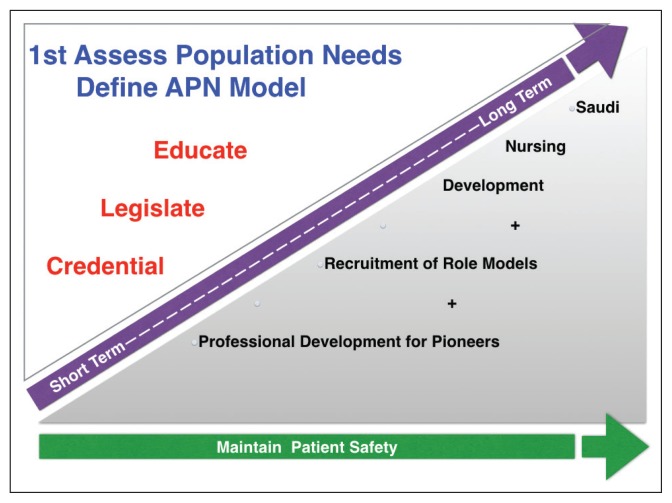

Following introductory presentations on APN globally and the experience in Saudi Arabia, a round table dialogue ensued which was enthusiastic, motivational and fruitful. The pearls of wisdom (Table 2) led to an agreement on the main themes represented in Figure 2, while laying the foundations for APN demonstrated by Figure 3. Ensuring that we remember the importance of caring for patients today, utilizing available human resources, while planning for the future of Saudi APN was one of the core themes (Figure 4). In moving forward, it is imperative that the MOH provides leadership in gathering experts to focus on the vision of APN (Table 3).

Table 2.

Pearls of wisdom.

| Define: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Assess: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Dos & Don’ts: |

|

|

|

Figure 2.

Advancing the practice of nursing: dialogue main themes.

Figure 3.

Laying the foundations.

Figure 4.

Care for patients today and plan for the future of advance practice nursing.

Table 3.

Moving Forward and Formulating a National Strategy.

|

DISCUSSION

Internationally there is understanding that the NP role fulfills a hybrid function, made possible by attaining a combination of nursing and medical knowledge and skills. In the USA, NPs and CNSs are strictly regulated, have protected titles, credentialing and privileging.25 Despite specialist advanced practice being evident since the 1900s26,27 there is still little consensus about these roles. In the UK support for role development has been driven by population needs and supported by the public and charitable organisations.28 There is a need for clarity with respect to areas of practice as well as the need to work towards registration and regulation in other countries.

The complexity of advanced practice in long-term conditions is well established. A good example is the management of hemoglobinopathy. Psychological assessment is thought to be a vital part of caring for patients with sickle cell disease. A study in the US reported sufferers had three times the risk of depressive symptoms than those without.29 These APNs independently manage patients’ pain in ambulatory care and reduce the need for hospitalisation.30

The unique selling point of advanced practice roles is not only the ability to manage complex care, but also to promote self-management. Far from being a simple physician substitute, a new kind of worker has evolved to meet patient needs often working well with physicians as part of a multidisciplinary team. Specialist nurses are attributed with adding value to the quality of care, being valued by both patients and other healthcare providers as the “key accessible professional.”31,32 Literature is emerging to suggest that specialty and community APNs are becoming invaluable in relation to service development, patient safety and quality of care in chronic conditions such as diabetes, bowel disease, Parkinson’s disease, heart failure, multiple sclerosis and many more.33 A rheumatology Specialty Nurse saved £300,000 a year by saving on physician time and reducing admissions.31,34 Specialty APNs involved in cancer care saved approximately £19 million.35,36

It is imperative to have a comprehensive, culturally tailored approach to the Saudi Arabian primary healthcare model and in caring for patients with chronic or complex conditions. This should include urgent reforms to ensure that there are adequate numbers of well-trained BSN nurses to provide high-quality nursing care, while paving the way for them to assume the role of the APN.

CONCLUSION

Despite the lack of legislation and regulation, APN has existed in Saudi Arabia since the 1990s, with patient needs driving its development ahead of formalisation. It is important to care for patients today while laying solid foundations for our APNs of the future. Due to the shortage of Saudi nurses, experienced expatriates are hired into APN roles. If prevented from practicing, as they are entitled to in their country of origin, they are difficult to retain. The need to address legislation is urgent; formal regulation will only be possible once nursing education is standardised and the profession of nursing is regulated. For pioneer APNs it is suggested that any missing educational preparation be obtained by organisations partnering with international universities. In the meantime nursing needs to step up and grasp the many opportunities that exist for the development of advanced practice roles in primary care and with specialty populations.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization Brief Intervention Study G. Switzerland 2013 2008–2012. Report No. WHO Nursing and Midwifery Progress Report 2008–2012. Report. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. Advanced Nursing Practice-A Position Statement. London: DOH; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. Nurse, midwife and health visitor consultants : establishing posts and making appointments. UK: Department of Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Council of Nurses. The Future of Nursing Leading Change. Washington DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinpell R, Scanlon A, Hibbert D, et al. Addressing Issues Impacting Advanced Nursing Practice Worldwide. Online J Issues Nurs. 2014;19:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peplau HE. Specialization in Professional Nursing. Nursing Science. 1965;3:268–87. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graydon J, Hendry J. Outpost nursing in Northern Newfoundland. The Canadian nurse. 1977;73:34–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stilwell B, Greenfield S, Drury M, Hull FM. A nurse practitioner in general practice: working style and pattern of consultations. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1987;37:154–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Storr G. The clinical nurse specialist: from the outside looking in. Journal of advanced nursing. 1988;13:265–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1988.tb01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manley K. A conceptual framework for advanced practice: an action research project operationalizing an advanced practitioner/consultant nurse role. Journal of clinical nursing. 1997;6:179–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamric AB, Hanson CM. Educating advanced practice nurses for practice reality. Journal of professional nursing : official journal of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. 2003;19:262–8. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(03)00096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brook S, Rushforth H. Why is the regulation of advanced practice essential? British journal of nursing. 2011;20:996, 8–1000. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.16.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scottish Government Health Department. Supporting the Development of Advanced Nursing Practice: A Toolkit Approach. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Leadership and Innovation Agency. Framework for Advanced Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professional Practice in Wales. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ketefian S, Redman RW, Hanucharurnkul S, Masterson A, Neves EP. The development of advanced practice roles: implications in the international nursing community. International nursing review. 2001;48:152–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2001.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Mahmoud SMP, Spurgeon P. Saudisation of the nursing workforce: Reality and myths about planning nurse training in Saudi Arabia. J Am Sci. 2012;8:369–79. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gazzaz L. Saudi nurses’ perceptions of nursing as an occupational choice: A Qualitative interview study. Nottingham: Nottingham; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organisation. World Health Statistics 2015. Switzerland: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. Guideline of Professional Classification and Registration for Health Practitioners. Saudi Arabia: SCFHS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hibbert D, Al-Sanea NA, Balens JA. Perspectives on specialist nursing in Saudi Arabia: a national model for success. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2012;32:78–85. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hibbert D, Rafferty L. The development of nurse-led bowel dysfunction clinics in Saudi Arabia: against all odds. Gastrointestinal Nursing. 2015;13:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryant-Lukosius D, Dicenso A, Browne G, Pinelli J. Advanced practice nursing roles: development, implementation and evaluation. Journal of advanced nursing. 2004;48:519–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hibbert D, Al-Dossari R. Developing enterostomal therapy as a nursing specialty in Saudi Arabia: which model fits best? Gastrointestinal Nursing. 2015;13:41–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.APRN Concensus Work Group & The National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Consensus Model for APRN Regulation: Licensure, Accreditation, Certification & Education. USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Witt K. Specialties in Nursing. The American Journal of Nursing. 1900;1:14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reiter F. The nurse-clinician. Am J Nurs. 1966;66:274–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trevatt P, Leary A. A census of the advanced and specialist cancer nursing workforce in England, Northern Ireland and Wales. European journal of oncology nursing : the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society. 2010;14:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenerette C, Funk M, Murdaugh C. Sickle cell disease: a stigmatizing condition that may lead to depression. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2005;26:1081–101. doi: 10.1080/01612840500280745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee L, Askew R, Walker J, Stephen J, Robertson-Artwork A. Adults with sickle cell disease: an interdisciplinary approach to home care and self-care management with a case study. Home Healthc Nurse. 2012;30:172–83. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0b013e318246d83d. quiz 83–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliver S, Leary A. Return on investment: workload, complexity and value of the CNS. British journal of nursing. 2012;21:32, 4–7. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2012.21.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mynors GP, Morse SM. Defining the Value of MS Specialist Nurses. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.COI Prime Minister’s Commissionon the Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England. Front Line Care: Report by the Prime Minister’s Commission on the Future of Nursing and Midwifery in England. London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.RCN, Leary A, Oliver S. Clinical nurse specialists: adding value to care. London: 2010. Report No. 003 598. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frontier Economics. One to one support for cancer patients: A REPORT PREPARED FOR DH. London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baxter J, Leary A. Productivity gains by specialist nurses. Nursing times. 2011;107:15–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]