Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

For Muslim patients confronted with chronic diseases, spirituality is an important resource for coping. These patients expect the health team to take care of the spiritual aspects. This study aimed to explore the spiritual aspects of care for chronic Muslim patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This qualitative-descriptive exploratory study was conducted in Isfahan, Iran, on a purposive sample of 25 participants, including patients, caregivers, nurses, physicians, psychologists, social workers, and religious counselors. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and analyzed through conventional content analysis.

RESULTS:

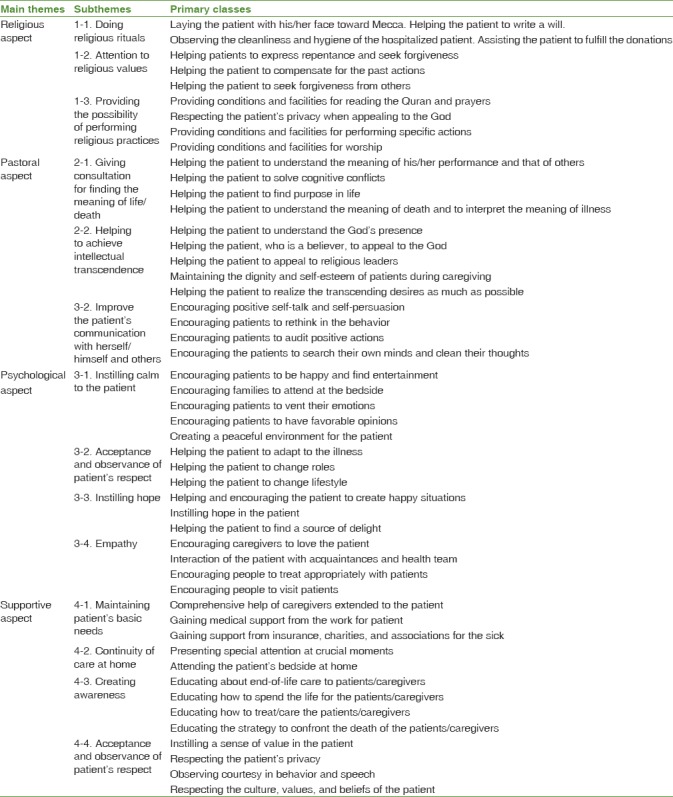

The spiritual aspects of care for chronic Muslim patients fell into four main themes. The first theme was religious aspect with the three subthemes of doing religious rituals, attention to religious values, and providing the possibility of performing religious practices. The second theme, i.e., pastoral aspect, consisted of three subthemes, namely giving consultation for finding the meaning of life/death, helping to achieve intellectual transcendence, and improve the patient's communication with herself/himself and others. The third theme was psychological aspect, the four subthemes of which included instilling calm to the patient, helping the patient to adapt, instilling hope, and empathy. Finally, the fourth theme was a supportive aspect and included the four subthemes of maintaining patient's basic needs, continuity of care at home, creating awareness, and acceptance and observance of patient's respect.

CONCLUSION:

Providing care based on the spiritual needs of chronic patients requires knowledge and skills that the health-care team need to provide through inter professional collaboration.

Keywords: Chronic disease, Iran, Muslim, patient, spiritual care, spirituality

Introduction

When a person is suffering from a chronic illness, he or she will face limitations in various activities and changes in social relations and experience drives, such as the need to find purpose, meaning, and hope in his/her life.[1] In these circumstances, spirituality is an individual's sense by which humans can feel significant and purposeful in life.[2] For these patients, it is essential to provide a comprehensive care plan that takes special attention to spirituality, in addition to physical and mental needs.[3]

However, three main questions are raised from members of the health-care team; these are: who can provide this care? with how much confidence should we enter into the privacy of patients' beliefs? and how can we meet these spiritual needs?[4] Hence, there is a need for cooperation between the members of the health-care team to use the capacity of different professionals in providing care with the spiritual aspect.[5,6]

In Iran, Islam is accepted by most Iranians. In Islam, spirituality is introduced as the basis of human evolution[7] and the most crucial aspect of the spiritual needs of Muslim patients in understanding the meaning of the human nature and their relationship with God.[8] Patients with chronic illnesses, especially with a disability, need the help of others to perform daily activities. This need is well met in Muslim societies because Islam lays stress on intimate and close relationships in the family and continued relationships of kinship.[9] They consider this kind of connection within the family as a means to ensure peace and life expectancy, and family members help each other during difficult circumstances.[10]

Since chronic patients need long-term care, they need to consider their spiritual challenges in planning comprehensive care,[11] Therefore, this study was considered. Many studies have been done on the spiritual needs of these patients and their spiritual care;[12,13,14] however, since spirituality at the core of human needs affects all aspects of care,[15] a study that identified aspects of care with spirituality has not yet been found. Accordingly, due to the abstract nature of spirituality, designing a qualitative study seemed essential and so this study was aimed to explore the spiritual aspects of care for chronic Muslim patients. The main study question was, “what are the spiritual aspects of care for chronic Muslim patients from the perspective of individual, family, and health-care team?”

Materials and Methods

Design and setting

This is a qualitative-descriptive exploratory study. Qualitative researchers interpret events in terms of participants' viewpoints.[16]

The study setting consisted of clinics, nursing homes, patients' private homes, and medical hospital wards (including cardiology, endocrinology, cancer, and respiratory care wards) in four teaching and nonteaching hospitals in Isfahan, Iran.

In this study, sampling was performed purposefully with a maximum variation to recruit 25 participants, including patients, family caregivers, nurses, physicians, psychologists, social workers, and religious counselors. Inclusion criteria for patients were an age of 20 or above and afflictions by chronic health conditions (such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, and cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases). Moreover, inclusion criteria for family caregivers were an age of 20 or above, he or she is one of the first-degree relatives, constantly taking care of the patient for >3 months at home, and provides companionship to patients during hospitalization. For the health-care team, the inclusion criterion was a work experience with patients, under the study of >3 years.

Data collection was done during May–November 2016 through semi-structured interviews by the first author in a place that was selected by the participants, such as a hospital waiting room. Interviews with patients, health-care team, and family caregivers were opened using the following statements: “What's in your mind in this condition?” “What would you like to do in this condition?” “What do you expect from others in this condition?” “What do you expect from God in this situation?” “Please speak about your experiences of chronic patients' expectations and providing spiritual care to them,” and “Please speak about your patient's expectations.” Subsequently, the supplementary questions led the interviews to the goals of the study, and the interviews were completed with in-depth questions such as “Please, explain more, if you can get an example.” One participant was interviewed twice and the others once. Interviews ranged in duration from 40 to 60 min. All interviews were recorded using an MP3 recorder.

Data analysis

The participants in this study included 14 patients, nine members of the health-care team, and two caregivers. Half of the participating patients were male. Moreover, two were single and 12 were married. The members of the health-care team had an average of 15 years of experience. All participants were Muslim. The researcher conducted 17 interviews with the client participants (i.e., the patients and the caregivers) and nine interviews with the health-care team. The analysis was conducted by conventional qualitative content analysis based on the method by Graneheim and Lundman. In this method, the categories and their names were obtained from data.[17] Immediately after conducting each interview, the first author listened to it twice and made a word-by-word transcript of it. Then, the interview transcript was divided into meaning units and the units were coded, compared with each other, and grouped into primary subthemes. After that, the first and the second authors independently read and compared subthemes and categorized them into main themes according to their similarities and differences. Finally, they compared their generated themes and developed a shared set of subthemes and themes. There are no criteria for determining sample size in a qualitative study, and sampling continues until data saturation in all categories, i.e. the data became saturated when new data are no longer produced.[18] In this study, data saturation occurred after 26 interviews with 25 participants. Yet, two more interviews were done with a patient and a nurse to ensure saturation. These two interviews yielded no new data.

Different techniques were used to ensure trustworthiness. For instance, member checking was done by asking two patients, one nurse, and one religious counselor to review and confirm our interpretations of the raw data. Moreover, during peer debriefing, the results of our analyses were reviewed and confirmed by ten experts in the areas of spirituality, qualitative research, and chronic diseases. The experts were external to this study. Transferability was ensured through sampling different age groups, educational levels, and fields of study. Moreover, two nurses and two physicians who were external to the study, but had the same experiences as study participants, were invited to review and confirm the similarity of our findings to their own experiences. An external audit was also performed by an experienced qualitative researcher.

Ethical considerations

The research proposal was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research (ethics code No. 395255). Before each interview, the intended interviewee was asked to read and sign the informed consent form of the study. Oral consent was given to participants to record their speeches. Interviews were anonymized using numerical codes. Participants were assured of their right to voluntarily withdraw from the study. Moreover, they were ensured that they would have access to psychological support if they experienced any negative consequence as a result of participation in the study. Of course, the study had no negative consequence for participants and none of them requested psychological support.

Results

In the present study, 14 subthemes were extracted that fell under four main themes of religious aspect, pastoral aspect, psychological aspect, and supportive aspect. Together with their subthemes, these main themes are explained in Table 1.

Table 1.

Classification of primary category, extracted subthemes, and main themes

Religious aspect

All patients believed that the health-care team will not stay indifferent regarding religious issues. They expected that religious ritual and values should be considered in their care. The subthemes belong to the following groups:

Doing religious rituals

Patients expected the health-care team to do religious rituals in their care. One of the nurses said: “Patients like to start with God's name when we do something for them. They like to keep us clean, dirt and other religious matters.” (EP2)

Attention to religious values

The patient's religious values included repentance and forgiveness, compensation for past actions, and attempts to obtain forgiveness from others, in which they needed help from the health-care team. One of the religious counselors said:

“Muslims like to seek forgiveness before death. They want God to forgive them for anything wrong, they might have said or did; they want people to forgive them or want to somehow compensate. It's the duty of all of us. This is the duty of everyone who somehow works for the patient.” (EP4)

Providing the possibility of performing religious practices

Reading the Quran and prayers, appealing, doing special deeds, and worshiping were the religious demands of the patients, and it is necessary to provide facilities and conditions to help them to use such facilities. One of the nurses said:

“We prepared a shelf in the ward. We put prayer books and Quran on it. At certain times, religious programs are held in the hospital and patients were informed by a megaphone. Materials needed for worshipping, such as the prayer rug and the tayammum stone, were placed in the room of a patient who cannot climb down the bed. But sometimes it's necessary to ask the patient if he needs something to help him to perform his religious practices.” (EP1)

In Iran, because the health-care team comprised Muslims, they pay attention to the religious aspects. Sometimes, they need to get consultation from a religious counselor who is ready to respond to the offices of the “Nasim Mehr” in hospitals.

Pastoral aspect

Patients with chronic illnesses often face profound challenges to understand the meaning of life, events, and its relationship with debilitating diseases that can affect their treatment and recovery. The following subthemes are placed in this group:

Giving consultation for finding the meaning of life/death

Patients with chronic illnesses always face challenges in understanding the meaning of their performance and that of others and finding the purpose of life and the meaning of death/illness affecting their thoughts and daily activities. Helping and guiding them to find the answers to these questions and resolving their mental conflicts are the responsibilities of the health-care team. One of the patients with respiratory failure said:

“Why I'm facing this plight? I don't deserve it. I have suffered so much in life. I did no bad for people. Then, why me? Cruel people are living a healthy life. I wish somebody distracted me from such thoughts.” (p. 8)

Helping to achieve intellectual transcendence

It is necessary for the health-care team to advise patients to put their trust in God, to appeal to religious leaders, and to help them to realize the transcending desires as much as possible. A religious counselor said:

“The patient kept saying that it was torture inflicted by God. We tried to clarify in multiple sessions that God is so kind and merciful that he won't punish anyone. The patient should not devalue himself. He must change his approach to the disease so that even in times of pain and suffering he could get close to human perfection.” (EP3)

Improve the patient's communication with herself/himself and others

Patients with chronic illnesses are disturbed by their internal conflicts with others and even themselves. The health-care team believed that positive self-talk, self-persuasion, reflection in behavior, auditing positive acts, searching for the mind, and training of cleansing bad thoughts should be considered for these patients. One psychologist said:

“Patients talk to themselves in private to contemplate on the past deeds to evaluate themselves and find crucial results that can influence their spirit and conditions. Here it is, our duty to encourage them to talk to themselves and direct their ideas and perceptions so as not to turn into negativity instilment.” (EP 8)

In Iran, consulting offices are established in order to provide pastoral care to patients in hospitals, associations, and charities. Yet, to provide desirable pastoral care, it is necessary to establish further collaboration between the health-care team, especially psychologists and clergymen.

Psychological aspect

Patients with chronic illnesses need to accept and adapt to the status quo to achieve peace of mind. Such care is in the scope of the duties of the health-care team. They need interprofessional collaboration to design a comprehensive program for each patient. The following subthemes are placed in this group.

Instilling calm to the patient

Patients with chronic illnesses search ways to happiness such as the presence of family, emotional drain, desirable thoughts, and a peaceful environment. The health-care team can pave the ground for the peace of mind for their patients. A diabetic patient with kidney failure, loss of vision, and loss of the left leg said: “I just want that you to tell me what should I do to get the bad thoughts out of my mind and relax?” (p. 1)

Helping the patient to adapt

Patients with chronic illnesses should find new styles for their lives and accept them. The health-care team should help the patient to cope with problems. The caregiver of a cancer patient said: “My patient tells me I became ugly and my daughter gets embarrassed in public. What to do with this problem?” (CP1)

Instilling hope

The health-care team can help create happy situations, thereby delivering what is desired by the patient and finding the source of happiness. A patient with heart failure stated:

“When I feel bad, my children rush me to the hospital. My wife measures my pulse all the way to the hospital. Their worries give me hope of being among them, I must recover. Humans get happy by such things.” (p. 2)

Empathy

Patients with chronic illnesses expected their family to love them, the health-care team to talk with them, and people behave with them appropriately. One psychologist said:

“For any person living with such respiratory conditions, who cannot sleep and live with harsh people around him, the only thing which can be done for his peace of soul is listen to him if he has got something to say, and help him if he needs help to show him that he is not alone. It is a must to make him feel that his disease has not alienated him from society. This is satisfying for him. I think it's our duty to teach this to our colleagues in the hospital.” (EP8)

In this study, the health-care teams consider it as their duty to help patients in this regard. Psychologists said that they could teach the health-care team the psychological practices of dealing with patients who are in spiritual crisis. Such interaction between psychologists and other members of the health-care team revealed the emphasis on interprofessional collaboration in the spiritual care.

Supportive aspect

Patients with chronic illnesses need the supportive care of the health-care team due to multiple problems. The following subthemes are placed in this group.

Maintaining patient's basic needs

It is crucial for the patient to receive comprehensive assistance from caregivers to obtain support from insurers, charities, and associations. The wife of a cancer patient said:

“I just believe in God so as not to be desperate. This poses big concerns for the patient with such situations. When he is admitted, I inform a nurse or a doctor, and they immediately call a woman social worker to come and she is very helpful to us.” (CP2)

Continuity of care at home

The concerns of patients with chronic illnesses should be resolved on how the care should be continued at home. A diabetic patient stated:

“I always think that what would happen if I get discharged and go home? Who will do my work? This foot always needs washing. What should I do if it suddenly goes black? I'm so sad. I always look up to God, who can help me. The woman on the first bed told me not to be upset and to ask nurses to introduce me to a charity that will handle my case.” (p. 5)

Creating awareness

It is necessary to educate patients and caregivers regarding the end-of-life care, living through life affairs, how to treat/care, and strategy to cope with death to reduce their anxiety. Health-care teams in this field have a duty to educate the patient in accordance with their expertise. A cancer patient said:

“I cannot stay alone. I always think that what would happen if my children go away and never return. Then, what should I do? I don't like to be alone when I die. I'm scared. I don't know what will happen in the future. My children don't know anything. Somebody who knows must drop by or at least explain what to do when something goes wrong at home.” (p. 9)

Acceptance and observance of patient's respect

Patients with chronic illnesses appreciate worthiness, respect for privacy, and respect shown toward the individual culture, values, and beliefs that they consider as instances of respect. A cancer patient stated:

“Now everyone who wants to do something here, abandoned my clothes without permission. It's so sad when I try to tell them that it makes me sad, they do not pay attention. Patients should be respected. And to accept that everyone has a framework for himself.” (p. 6)

In Iran, supportive care is provided in specific circumstances to each patient. It seems that such care is neglected to a great extent. Special attention must be paid to such care to change the beliefs and attitudes of the health-care team.

Discussion

In this study, the four spiritual aspects of care that were discovered were religious, pastoral, psychological, and supportive aspects. In the religious aspect of care, it has been observed that chronic Muslim patients, despite their limitations and disabilities, are concerned about doing their religious practices, and it is important for them that the health-care team should pay attention to their beliefs and some of the religious practices they emphasize. These issues are also of great interest to caregivers of patients. They tried to help the patient to perform religious practices such as praying. Other studies, while confirming these findings, have stated that the health-care team should find evidence of their religiosity and accordingly guide the doctors and nurses to work according to their religious needs.[19,20] Interprofessional collaboration with a religious advisor is essential for the planning of religious care for each patient.[21,22]

Another spiritual aspect of care includes pastoral aspect. Explaining the goal and outcome of this aspect of care, studies state that the pastoral care is a set of actions that help to meet the needs and cognitive problems of patients and help understand their conflicts about illnesses/death/life.[23] Psychologists and religious counselors reported that they could help provide this care to other members of the health-care team and other studies confirm this collaboration.[24]

When a chronic patient is in an inappropriate health situation and is constantly worried about his/her future conditions, communicating with the health team, giving mentality, creating empathy, etc., were considered as the psychospiritual aspects of care. Psychological aspect of care is greatly linked with spiritual care in this study to help the patient to achieve peace of mind and accept the status quo. In another study, researchers stated that spirituality is a kind of intelligence whose dimensions consist of motivational psychology, perception, and recognition, and these dimensions must be strengthened in people[25] and psychologists should help the health-care team in providing spiritual care.[26] That is consistent with the results of this study.

In this study, supportive care was considered as a spiritual aspect of care. The results showed that the spiritual support of patients in addressing the concerns that arose from lifestyle changes, including financial problems and home care, could help to cope with disability and increase the level of tolerance. Studies show that supporting and helping patients regarding their concerns and making them aware of their disease are part of care; they are provided in the form of spiritual care.[27] Social workers can help chronic patients to afford health care costs.[28]

In this study, the health-care team believed that the team must cooperate through teamwork in investigating the needs of patients, and the interprofessional collaboration should be considered in the care policy.[29] The results are consistent with those of other studies. It is suggested that for achieving this goal, the culture of teamwork and patient referral system to the relevant expert should be considered.

Conclusion

In the sociocultural context of Iran, where religion plays an integral role, spirituality is significant in terms of the experience of illness and recovery. The researchers found that care must be taken with spiritual aspects, where each aspect completes the others and requires expertise and skill. Thus, to meet the spiritual aspect of care, there is a need for the presence of believers and familiar people with the fundamentals of such care in the health-care team. These experts would consider the spiritual needs, desires, and concerns of patients by closely collaborating and interacting with them, thereby providing patients with comprehensive care to endure the pain, suffering from illnesses, and disabilities.

One of the limitations of the study was that the study sample was conducted among the population of Isfahan, Iran, in which there is a marked sensitivity to religion, culture, and spirituality.[30] It should be noted that the choice of this research environment was to give the participants more access and attempt to extract the aspects of spiritual care in the same cultural context. Therefore, the results of this study may not reflect all spiritual aspects of care in other subcultures of Iran.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was conducted with the financial support of the Deputy for Researches at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (proposal code No. 395255).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors sincerely acknowledge the contributions of the participants in educational and noneducational centers in Isfahan.

References

- 1.Bekelman DB, Hutt E, Masoudi FA, Kutner JS, Rumsfeld JS. Defining the role of palliative care in older adults with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2008;125:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallurupalli M, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, Phelps AC, Block SD, Ng AK, et al. The role of spirituality and religious coping in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koenig HG. Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: A review. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:283–91. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yardley SJ, Walshe CE, Parr A. Improving training in spiritual care: A qualitative study exploring patient perceptions of professional educational requirements. Palliat Med. 2009;23:601–7. doi: 10.1177/0269216309105726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hospice & Palliative Nursing Association. HPNA position statement spiritual care. 2013. [Last accessed on 2015]. Available from: http://hpna.advancingexpertcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Spiritual-Care-Position-Statement-FINAL-1010.pdf .

- 6.Kalish N. Evidence-based spiritual care: A literature review. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6:242–6. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e328353811c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isgandarova N. The evolution of Islamic spiritual care and counseling in Ontario in the context of the college of registered psychotherapists and registered mental health therapists of Ontario. J Psychol Psychother. 2014;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cobb M, Dowrick C, Lloyd-Williams M. What can we learn about the spiritual needs of palliative care patients from the research literature? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:1105–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quran Holy. Translated Ayatollah Al-ozma Naser Makarem Shirazi. Qom: Imam Ali Ebne Abi Taleb (Ýa); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arzani H. Ethical responsibility of children to wards their parents in the QURAN and the BIBLE. Ethics. 2014;3:12–169. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards A, Pang N, Shiu V, Chan C. The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: A meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med. 2010;24:753–70. doi: 10.1177/0269216310375860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jafari N, Loghmani A, Puchalski CM. Spirituality and health care in Iran: Time to reconsider. J Relig Health. 2014;53:1918–22. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9887-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fradelos EC, Tzavella F, Koukia E, Papathanasiou IV, Alikari V, Stathoulis J, et al. Integrating chronic kidney disease patient's spirituality in their care: Health benefits and research perspectives. Mater Sociomed. 2015;27:354–8. doi: 10.5455/msm.2015.27.354-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jors K, Büssing A, Hvidt NC, Baumann K. Personal prayer in patients dealing with chronic illness: A review of the research literature. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015. 2015:927973. doi: 10.1155/2015/927973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adib-Hajbaghery M, Zehtabchi S. Assessment of nurses' professional competence in spiritual care in Kashan Hospitals in 2014. Sci J Hamadan Nurs Midwifery Fac. 2015;22:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grove SK, Burns N, Gray JR. Us: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014. Understanding Nursing Research: Building An Evidence-Based Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heidari S, Rezaei M, Sajadi M, Ajorpaz NM, Koenig HG. Religious practices and self-care in Iranian patients with type 2 diabetes. J Relig Health. 2017;56:683–96. doi: 10.1007/s10943-016-0320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sartori P. Spirituality 1: Should spiritual and religious beliefs be part of patient care? Nurs Times. 2010;106:14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi PJ, Curlin FA, Cox CE. “The patient is dying, please call the chaplain”: The activities of chaplains in one medical center's Intensive Care Units. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:501–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marin DB, Sharma V, Sosunov E, Egorova N, Goldstein R, Handzo GF, et al. Relationship between chaplain visits and patient satisfaction. J Health Care Chaplain. 2015;21:14–24. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2014.981417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khodayar D, Ghaemi M. The Quran view to educational functions and its role in spiritual health mental health. J Med Ethics. 2016;7:55–91. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Proserpio T, Piccinelli C, Clerici CA. Pastoral care in hospitals: A literature review. Tumori. 2011;97:666–71. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emmons RA. Is spirituality an intelligence? Motivation, cognition, and the psychology of ultimate concern. Int J Psychol Relig. 2000;10:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zollfrank AA, Trevino KM, Cadge W, Balboni MJ, Thiel MM, Fitchett G, et al. Teaching health care providers to provide spiritual care: A pilot study. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:408–14. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delgado-Guay M, Ferrer J, Rieber AG, Rhondali W, Tayjasanant S, Ochoa J, et al. Financial distress and its associations with physical and emotional symptoms and quality of life among advanced cancer patients. Oncologist. 2015;20:1092–8. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canda ER, Furman LD. Spiritual Diversity in Social Work Practice: The Heart of Helping. UK: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irajpour A, Ghaljaei F, Alavi M. Concept of collaboration from the Islamic perspective: The view points for health providers. J Relig Health. 2015;54:1800–9. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9942-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moeini M, Sharifi S, Kajbaf MB. Effect of islam-based religious program on spiritual wellbeing in elderly with hypertension. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2016;21:566–71. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.197683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]