Abstract

Aortic dissection in young patients presents a clinical and diagnostic challenge. Atypical symptoms of ascending aortic dissection can delay presentation and diagnosis. Here, we describe a patient with delayed diagnosis of an atypical presentation of ascending aortic dissection after using a synephrine-containing pre-workout supplement. The diagnosis was initially missed on computed tomography, but subsequently made on echocardiography. This is the first reported case of ascending aortic dissection in the setting of synephrine supplementation. This case illustrates a potential cardiovascular adverse effect of synephrine and highlights the need for clinical trials without conflicts of interest assessing its safety.

<Learning objective: The aims of this report are to highlight the diagnostic challenge of an atypical presentation of ascending aortic dissection and to illustrate a potential cardiovascular adverse effect of synephrine supplementation.>

Keywords: Aortic dissection, Synephrine, Aortopathy, Citrus aurantium, Bitter orange, Echocardiography

Introduction

Dietary and workout supplements are popular among young people. Synephrine, a sympathomimetic agent commonly used in these supplements, has recently come under scrutiny for its potential cardiovascular adverse effects. This case illustrates an atypical presentation of ascending aortic dissection (AoD) following synephrine consumption, missed on initial imaging and misdiagnosed as acute coronary syndrome. The patient was subsequently found to have ascending AoD on echocardiography. Atypical symptoms of ascending AoD can delay presentation and diagnosis, as in our patient’s case. This report highlights the diagnostic challenge of an atypical presentation of AoD and describes a potential cardiovascular adverse effect of synephrine-containing workout supplements.

Case report

A 38-year-old male with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with a syncopal episode and hypotension. He had chronic use of energy drinks and C4 pre-workout supplement—containing high amounts of caffeine and synephrine—to enhance workout performance, and consumed two doses of C4 within one hour of symptom onset. For many years he had taken one to two doses (about 300 mg caffeine equivalent) of C4 prior to his workouts. He denied taking any other medications or supplements.

Physical examination revealed a robust physical frame with no Marfanoid features, hypotension, and tachycardia with 3/6 diastolic murmur at the left mid thorax. Initial troponin was indeterminate at 0.10 ng/mL (reference range less than 0.04 ng/mL). His other initial laboratory work was notable for creatinine of 1.39 mg/dL and blood urea nitrogen of 16 mg/dL. The complete blood count, electrolyte panel, D-dimer, hypercoagulability panel, and liver function tests all were within normal limits. Urine drug screen was negative. Electrocardiography exhibited ST depressions in the inferior and anterolateral leads with J point elevation in aVR. Chest radiograph showed mild degree of pulmonary edema and did not reveal mediastinal widening. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest depicted no obvious evidence of AoD or pulmonary embolism, but revealed ascending aortic dilation of 4.9 cm. With the diagnosis of AoD initially excluded, heparin drip was started for suspected acute coronary syndrome.

Over the next several hours, the patient clinically declined. Initial hypotension was unresponsive to fluid boluses, and the patient was subsequently started on dopamine drip. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated ascending AoD extending to the left subclavian artery, tricuspid aortic valve with severe aortic regurgitation, moderate left ventricular dilatation with a mildly depressed ejection fraction (40%), and severe pulmonary hypertension approaching systemic levels (>80 mmHg) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 ). Heparin drip was immediately discontinued. The patient underwent emergent AoD repair with aortic graft replacement and resuspension of the aorta. Postoperatively, he was weaned off pressors and was ambulating without symptoms. Creatinine improved to 1.1 mg/dL with supportive care. He was advised to stop consuming C4 dietary supplement and energy drinks. He was started on carvedilol, lisinopril, and simvastatin. At 6-month follow up, the patient remained free of symptoms, and his ejection fraction improved to 54% on nuclear imaging.

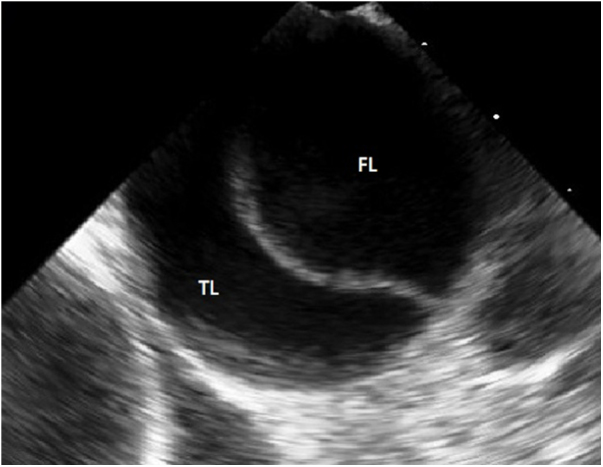

Fig. 1.

Ascending aortic dissection seen on cross-section of the ascending aorta on echocardiography. True lumen (TF) and false lumen (FL) are separated by a dissection flap.

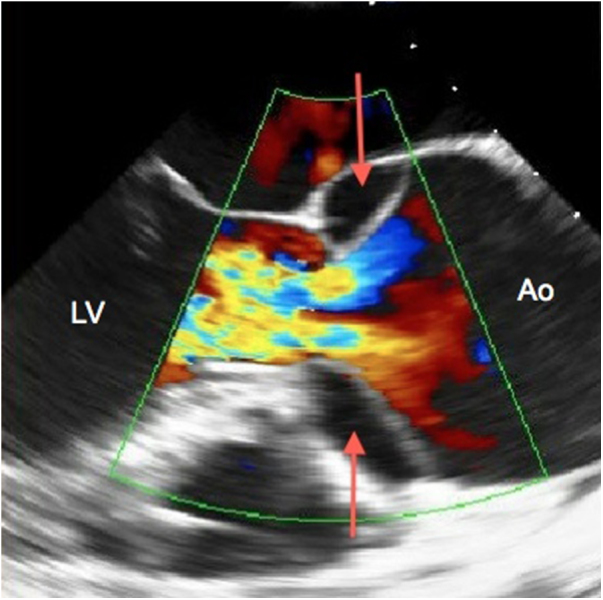

Fig. 2.

Severe aortic regurgitation and ascending aortic dissection seen on echocardiography with Doppler. Entry points of the false lumen of the dissection are indicated (red arrows).

LV, left ventricle; Ao, ascending aorta.

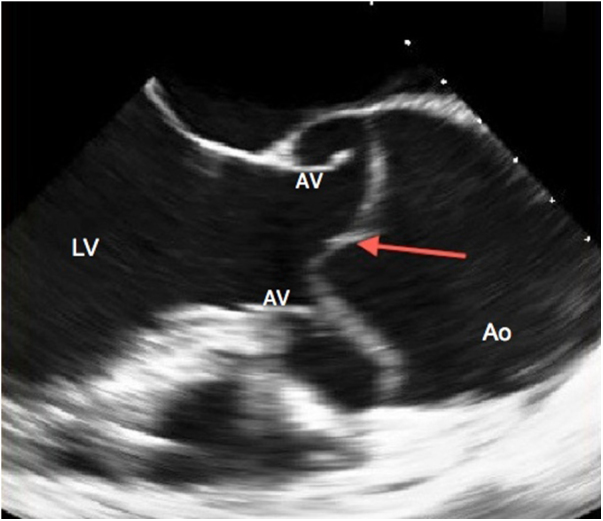

Fig. 3.

Ascending aortic dissection with dissection flap (arrow) seen on echocardiography. It also showed moderate left ventricular dilatation with a mildly reduced ejection fraction (40%), and severe pulmonary hypertension approaching systemic levels (>80 mmHg).

AV, aortic valve; LV, left ventricle; Ao, ascending aorta.

Discussion

AoD is the most lethal condition involving the aorta and has an incidence of about 5–30 cases per million [1]. It is rare in young patients, with only 7% of all AoD cases occurring in people under 40 years [1], [2]. Ascending or Type A AoD, which is defined as dissection of the aorta proximal to the subclavian artery, typically has a poor prognosis, and diagnosis is often delayed or missed, resulting in a high mortality rate with 40% of patients dying soon after onset of symptoms and 1% dying per hour thereafter [1], [2]. Prompt medical attention and accurate diagnosis are crucial in ascending AoD patients, as early surgical treatment is curative [1], [2]. This distinction can be difficult on clinical grounds alone but can be suggestive on CT— a tool often used as one of the initial screening imaging modalities.

According to the 2010 American Heart Association statistics, many patients presenting with AoD have delayed or missed diagnosis by physicians [1]. One of the proposed reasons for this is the atypical presenting symptoms of a subset of AoD patients. Pain is the most common presenting symptom of AoD, comprising about 94% of patients [1]. Syncope, as seen in our patient, is an uncommon atypical presentation of AoD, comprising 13% of cases, and is associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality according to the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD), which is the largest database of patients with AoD [1], [2], [3]. Painless AoDs occur in 6% of AoD patients and are associated with an increased mortality and morbidity rate compared to those presenting primarily with pain [1], [3]. Hypotension, as seen in our patient, is an ominous finding in patients presenting with AoD [1].

AoD occurs in conditions that increase pressure of blood exerted on the vessel wall and contribute to medial wall degeneration [2]. The most common causes of AoD in patients under 40 years are Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, Loey–Dietz syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, prior aortic valve surgery, hypertension, stimulant use (such as cocaine), weight-lifting with valsalva, Takayasu’s arteritis, and familial thoracic aortic aneurysm [1], [2], [4].

Pre-workout supplements are common among young people to enhance their training. Ephedrine, an alkaloid found in the Ephedra sinica or Ma Huang plant, was used in weight loss and workout enhancing supplements for years [5], [6]. In 2004, ephedrine was banned by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for serious adverse events including myocardial infarction, stroke, seizures, and death [5], [6]. Since the ban, non-ephedrine containing dietary and metabolic supplements have emerged, which contain stimulants such as synephrine. Synephrine, a proto alkaloid found in Citrus aurantium (or bitter orange) fruit, has sympathomimetic and structural similarities to ephedrine and is also an alpha- and beta-adrenergic agonist [7], [8]. Synephrine-containing supplements have recently come under scrutiny for concern of significant cardiovascular adverse effects. There are several case reports describing adverse effects of synephrine including myocardial infarction, stroke, and tachycardia [8], [9], [10]. One case report described ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in a 24-year-old healthy active man, who had absence of other contributory risk factors [9].This present case is the first reported case of ascending AoD in the setting of synephrine supplementation.

While it is difficult to prove, this case raises suspicion of synephrine supplementation contributing to his previously undetected aortopathy, causing augmented wall stress, aortic dilation, and intimal weakening, which led to acute ascending AoD. Despite advances in diagnostic imaging modalities, the diagnosis of ascending AoD can be missed or delayed, as in our patient. Thus, the most important factor in accurate diagnosis of AoD is having a high clinical suspicion especially in the setting of unrevealing initial screening. When screening tests such as chest radiography or CT cannot adequately exclude the diagnosis of ascending AoD, subsequent imaging such as comprehensive echocardiography is necessary to establish or refute the diagnosis. Furthermore, this case illustrates a potential cardiovascular adverse effect of synephrine and necessitates the need for clinical trials without conflicts of interest assessing the safety of synephrine supplementation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hiratzka L.F., Bakris G.L., Beckman J.A., Bersin R.M., Carr V.F., Casey D.E., Eagle K.A., Hermann L.K., Isselbacher E.M., Kazerooni E.M., Kouchoukos N.T., Lytle B.W., Milewicz D.M., Reich D.L., Sen W. ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. JACC. 2010;55:1509–1544. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann D.L., Zipes D.P., Libby P., Bonow R.O., Braunwald E. 10th ed. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2015. Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park S.W., Hutchison S., Mehta R.H., Isselbacher E.M., Cooper J.V., Fang J., Evangelista A., Llovet A., Nienaber C.A., Suzuki T., Pape L.A., Eagle K.A., Oh J.K. Association of painless acute aortic dissection with increased mortality. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1252–1257. doi: 10.4065/79.10.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Januzzi J.L., Isselbacher E.M., Fattori R., Cooper J.V., Smith D.E., Fang J., Eagle K.A., Mehta R.H., Nienaber C.A., Pape L.A. Characterizing the young patient with aortic dissection: results from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD. JACC. 2004;43:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NIH Office of Dietary Supplements: Ephedra facts. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/EphedraandEphedrine-HealthProfessional/. July 2004.

- 6.Haller C.A., Benowitz N.L. Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1833–1838. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012213432502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haaz S., Fontaine K.R., Cutter G., Limdi N., Perumean-Chaney S., Allison D.B. Citrus aurantium and synephrine alkaloids in the treatment of overweight and obesity: an update. Obesity Rev. 2006;7:79–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bitter orange (Citrus aurantium var. amara) extracts and constituents (±)-p-synephrine [CAS No. 94-07-5] and (±)-p-octopamine [CAS No. 104-143]. Review of Toxicological Literature. Contract No. N01-ES-35515. National Toxicology Program: June 2004. p. 1–73.

- 9.Thomas J.E., Munir J.A., McIntyre P.Z. Ferguson MA.STEMI in a 24-year-old man after use of a synephrine-containing dietary supplement. A case report and review of the literature. Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36:586–590. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nykamp D.L., Fackih M.N., Compton A.L. Possible association of acute lateral-wall myocardial infarction and bitter orange supplement. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:812–816. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]