Abstract

Recent reports describing lymphatic vasculature in the meninges have challenged the traditional understanding of interstitial solute clearance from the central nervous system, although the significance of this finding in human neurological disease remains unclear. To begin to define the role of meningeal lymphatic function in the clearance of interstitial amyloid beta (Aβ), and the contribution that its failure may make to the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), we examined meningeal tissue from a case series including AD and control subjects by confocal microscopy. Our findings confirm the presence of lymphatic vasculature in the human meninges and indicate that, unlike perivascular efflux pathways in the brain parenchyma in subjects with AD, Aβ is not deposited in or around meningeal lymphatic vessels associated with dural sinuses. Our findings demonstrate that while the meningeal lymphatic vasculature may serve as an efflux route for Aβ from the brain and cerebrospinal fluid, Aβ does not deposit in the walls of meningeal lymphatic vessels in the setting of AD.

Keywords: Lymphatic, meninges, Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid beta, podoplanin, LYVE-1

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia worldwide and is diagnosed histopathologically by the presence of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles and extracellular amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques (Glabe, 2005; Selkoe, 2001). In sporadic AD, production of Aβ remains relatively stable during the aging process, yet the slowing of Aβ clearance observed among aging and AD subjects suggests that impairment of endogenous Aβ clearance may underlie Aβ deposition in the human brain (Mawuenyega et al., 2010; Patterson et al., 2015). Aβ is removed from the brain interstitium through several mechanisms, including local cellular degradation, receptor-mediated efflux across the blood-brain barrier, and perivascular exchange into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) compartment via the glymphatic system (Iliff et al., 2012; Ramanathan et al., 2015; Tarasoff-Conway et al., 2015).

The characterization of a meningeal lymphatic vascular system in mice has important implications for our understanding of interstitial homeostasis in the brain and central nervous system (CNS), CSF physiology, and CNS immune surveillance (Aspelund et al., 2015; Iliff et al., 2015; Louveau et al., 2015). These findings were recently confirmed in three human subjects and in nonhuman primates by Absinta et al. (Absinta et al., 2017) who visualized the meningeal lymphatic network by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and immunohistochemical detection of meningeal lymphatic vessels with molecular markers of lymphatic endothelial cells. In both mice and humans, meningeal lymphatic vessels are distributed along large blood vessels and cranial nerves in the dura mater, reflecting patterns observed in the peripheral lymphatic vasculature. In mice, meningeal lymphatic vessels absorb macromolecules from the brain and CSF and transport these solutes to the deep cervical lymph nodes (DCLNs). This efflux route provides an anatomical basis for the experimental observation that molecules introduced into the CNS accumulate in the DCLNs (Boulton et al., 1999; Bradbury and Cole, 1980; Cserr et al., 1992). Although meningeal lymphatic function remains largely unexplored, this pathway is speculated to play an important role in the clearance of pathological waste products such as Aβ from the brain interstitium and CSF (Louveau et al., 2017; Tarasoff-Conway et al., 2015). However, to our knowledge, no studies have evaluated whether changes in meningeal lymphatic vessel structure or function are observed in the setting of AD. It also remains unclear if Aβ is deposited in the walls of meningeal lymphatic vessels as has been observed along leptomeningeal and intraparenchymal arteries in the cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) that is present in more than 90% of AD brains (Kalaria and Ballard, 1999).

2. Methods

2.1. Human Tissue Samples

Samples were collected after obtaining consent from subjects or legal next of kin as part of donation to the Oregon Brain Bank. During the autopsy, human dural tissue containing the superior sagittal sinus was collected by pathologists at Oregon Health & Science University. Samples were fixed in 10% formalin for variable time periods before being processed and embedded in paraffin. This manuscript does not contain any identifiable personal patient information. Braak neurofibrillary tangle and CERAD amyloid plaque scores of AD-related pathologies were determined by standard procedures (Braak and Braak, 1995; Mirra et al., 1991). Non-AD diagnoses were established via comprehensive gross and histopathologic exam as described elsewhere (Erten-Lyons et al., 2013). Throughout tissue preparation and image acquisition, researchers were blinded to the subjects’ demographic information and diagnosis.

2.2. Tissue Preparation

7 μm coronal sections of paraffin-embedded human dura and superior sagittal sinus were cut and mounted on glass slides (Star Frost). Slides were baked at 50°C overnight, deparaffinized using citrus clearing solvent, rehydrated using graded steps of ethanol, and rinsed in distilled water.

2.3. Immunofluoresence

Tissues were incubated in 10% formic acid for 10 minutes, steamed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 30 minutes, and incubated overnight at 4°C in 0.3% PBS triton with 2% donkey serum, 2.5% bovine serum albumin blocking buffer. Tissues were then incubated in primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C (1:40 D240 Podoplanin mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:800 4G8 pan-Aβ mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:300 6E10 pan-Aβ mouse monoclonal antibody BioLegend 803001, 1:100 LYVE1 rabbit polyclonal antibody Abcam 36993, 1:500 α-smooth muscle actin polyclonal antibody Abcam ab5694, 1:300 rabbit CD31 antibody Abcam ab28364). Corresponding fluorescent secondary antibodies were diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer and were incubated overnight at 4°C. Tissues stained with Hoechst 33342 were incubated in 1:50,000 working solution for 10 minutes. Tissues stained with X-34 (Sigma) were incubated in 500 μM X-34 for 10 minutes, rinsed in DI water, incubated in 0.2% NaOH/80% EtOH for 2 minutes, and rehydrated in DI water for 10 minutes (Styren, et al., 2000). Slides were mounted using mowiol 4–88 mounting media (Sigma, cat. 81381). Because the podoplanin and Aβ (6E10 and 4G8) antibodies were generated in the mouse, sequential sections were stained and compared to identify co-localized immunoreactivity.

2.4. Confocal Microscopy and Spectral Unmixing

Images were acquired in single frames or z-stacks using the Zeiss LSM 880 with a 20x objective. Due to abundance of autofluorescent material in the aged human meninges, a spectral unmixing strategy was implemented to separate nonspecific background signal from signal due to antibody binding. Specifically, the spectral profile of signal emitted during excitation in lambda mode was measured in unstained, Hoechst only, and Hoechst + secondary antibody treated meningeal tissue samples. After identifying the spectral signature of nonspecific signals in these reference tissues, spectrally separated images were acquired in real time using Emission Fingerprinting. Post image processing (including image thresholding, noise reduction, and maximum intensity z-stack projections) was carried out using ImageJ software.

3. Results

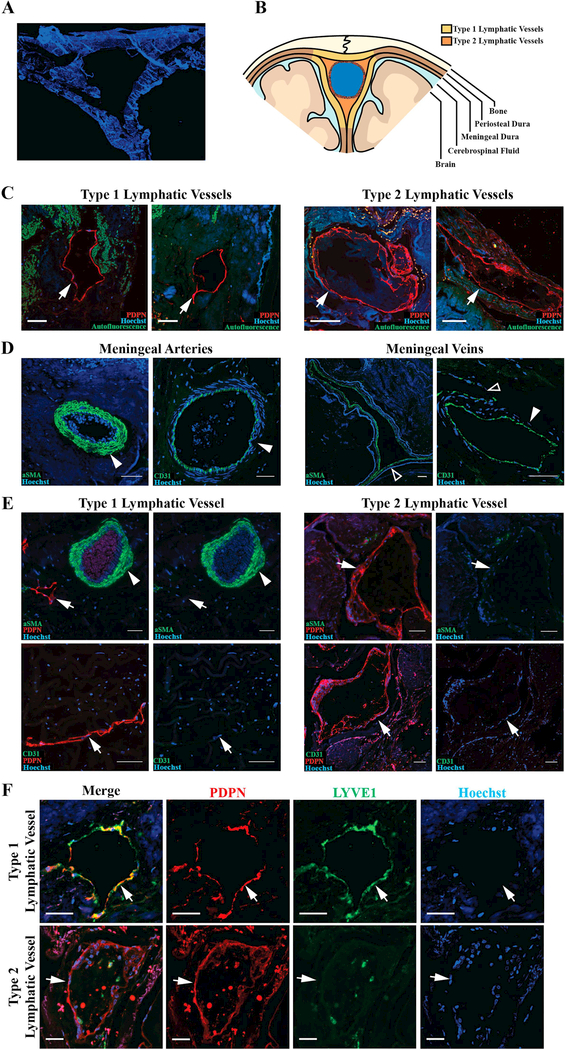

To define the presence and distribution of lymphatic vessels in human meningeal tissue, we used immunofluorescence in post mortem coronal sections of superior sagittal sinus (SSS, Figure 1A-B) derived from control subjects (n=5), AD subjects (n=6) and diagnosed with mixed dementia or other neurological diseases (n=10). Demographic information including age at death, gender, clinical-pathological diagnosis, Braak stage, and Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) score (neuritic Aβ plaque burden) for each subject are reported in Table 1. To visualize podoplanin (PDPN, a lymphatic endothelial cell marker) immunofluorescence across the large SSS histological sample, we employed whole-slide fluorescence microscopy. Individual PDPN+ lymphatic vessels were visualized by high resolution microscopy with spectral unmixing to segment out tissue autofluorescence. We observed PDPN+ vessels in 19/21 subject samples, including 6/6 AD subjects, 4/5 control subjects, and 9/10 subjects with mixed dementia or other neurological diseases (Table 1).

Figure 1. Lymphatic vessels with variable morphology invest the human meninges.

A. Representative image of coronal section of human superior sagittal sinus and meninges. B. Schematic demonstrating regions of the meninges where lymphatic vessels were found. Yellow regions represent the general distribution of Type 1 vessels and orange regions represent Type 2 vessels. C. Representative images of Type 1 and 2 lymphatic vessels (arrows). D. Dural blood vessels, including arteries (solid arrowhead) and veins (hollow arrowhead), labeled with vascular smooth muscle cell marker alpha-smooth muscle actin (aSMA) and the blood endothelial cell marker CD31. E. Dural lymphatic vessels do not co-label with aSMA or CD31. F. Type 1 vessels are PDPN+LYVE1+ and Type 2 vessels are PDPN+LYVE1-. Scale bars in C and D represent 100 μm and bars in E and F represent 50 μm.

Table 1.

Description of pathology observed in meninges and brain of individual subjects included in the study. M, Male, F Female. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; LBD, Lewy Body Dementia; HPC, hippocampal; FTD, frontal temporal dementia; MS, multiple sclerosis; PD, Parkinson’s disease; NA, not applicable (Braak staging in control subjects were not evaluated).

| Subject | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | Braak Stage | CERAD Score | Type 1 Lymphatic Vessels | Type 2 Lymphatic Vessels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35 | F | Control | NA | 0 | + | + |

| 2 | 73 | M | Control | NA | 0 | + | + |

| 3 | 11 | M | Control | NA | 0 | − | − |

| 4 | 75 | M | Control | NA | 0 | + | + |

| 5 | 41 | M | Control | NA | 0 | + | + |

| 6 | 57 | M | AD | 6 | 3 | − | + |

| 7 | 70 | M | AD | 6 | 3 | + | + |

| 8 | 85 | F | AD | 6 | 2 | + | + |

| 9 | 86 | F | AD | 6 | 2 | + | + |

| 10 | 69 | F | AD | 6 | 3 | + | + |

| 11 | 79 | M | AD | 6 | 2 | + | + |

| 12 | 75 | F | AD and LBD | 6 | 1 | − | + |

| 13 | 89 | F | LBD | 4 | 1 | + | + |

| 14 | 85 | M | LBD | 3 | 0 | + | − |

| 15 | 74 | M | LBD, HPC Sclerosis | 4 | 0 | − | + |

| 16 | >89 | F | HPC Sclerosis | 4 | 1 | − | − |

| 17 | 73 | F | FTD/Tau | 3 | 0 | − | + |

| 18 | 79 | M | MS | 2 | 0 | + | + |

| 19 | 71 | M | PD | 0 | 0 | − | + |

| 20 | 70 | F | Psychosis | 0 | 0 | − | + |

| 21 | 66 | F | Leukoencephalopathy | 1 | 0 | + | + |

PDPN+ lymphatic vessels with two distinct morphologies were observed in human postmortem SSS samples. One vessel type reflected traditional initial lymphatic morphology, with a single layer of endothelium, no smooth muscle or red blood cells, unoccupied lumen, and irregular morphology (Figure 1C). For simplicity, these PDPN+ vessels were termed “Type 1” lymphatic vessels. A second vessel type, termed “Type 2”, was observed that exhibited an irregular endothelial border and material within the lumen, resembling the lymphatic vessels described in human autopsy samples by Louveau and colleagues (Louveau et al., 2015) (Figure 1C). In contrast to meningeal arteries and veins (Figure 1D), both vessel types were negative for the blood endothelial cell marker CD31 (Figure 1E), indicating that PDPN+ Type 1 and Type 2 vessels are not meningeal blood vessels. Like other peripheral lymphatic vessels, Type 1 vessels also labeled with the LYVE-1, however Type 2 vessels did not (Figure 1F). Type 1 and 2 lymphatic vessels exhibited specific distributions within the dural tissue, with Type 1 vessels distributing within the periosteal and meningeal layers of the dura mater, and Type 2 vessels distributed between the SSS and periosteal layer of the dura (Figure 1B). As reported in the rodent, lymphatic vessels of both types were negative for the vascular smooth muscle cell marker smooth muscle actin (Figure 1E).

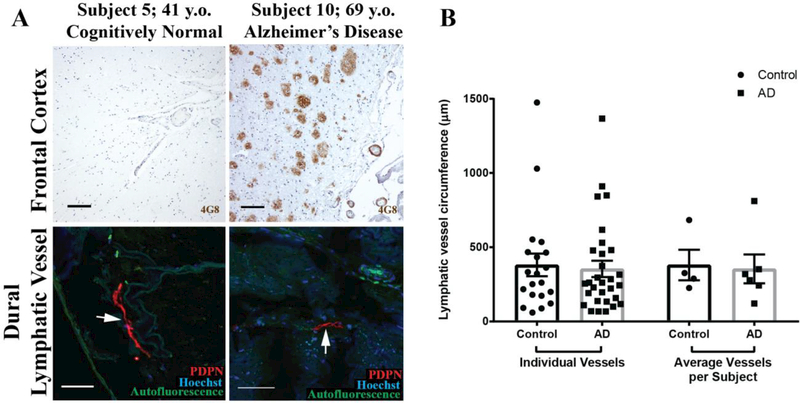

Both Type 1 and 2 lymphatic vessels were readily detectable in both control and AD subjects (Figure 2A, Table 1). To determine if there were structural differences in the lymphatic vessels of AD and control subjects, we measured the circumference of 5 lymphatic vessels per subject. We found no difference in lymphatic vessel circumference between AD and control subjects, with an average circumference of 354 ± 55 μm and 381 ± 76 μm, respectively (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Meningeal lymphatic vessels in AD and control subjects.

A. Frontal cortical Aβ plaques and leptomeningeal vascular Aβ deposition in control and AD subjects. Type 1 and Type 2 meningeal lymphatic vessels (arrows) are readily detected among both groups. B. Quantification of lymphatic vessel circumference (14 Type 1 and 6 Type 2 vessels in control subjects; 22 Type 1 and 8 Type 2 in AD subjects). Columns on left reflect all vessels from all subjects (n = 20 and 30 from control and AD subjects, respectively). Columns on right reflect subject-wise averages of lymphatic vessel circumferences (n = 4 and 6 control and AD subjects, respectively). No group-wise differences in lymphatic vessel circumference were observed (unpaired two-tailed T-test with Welch’s correction, p= 0.78 and 0.85 for individual vessels and average vessels per subject, respectively).

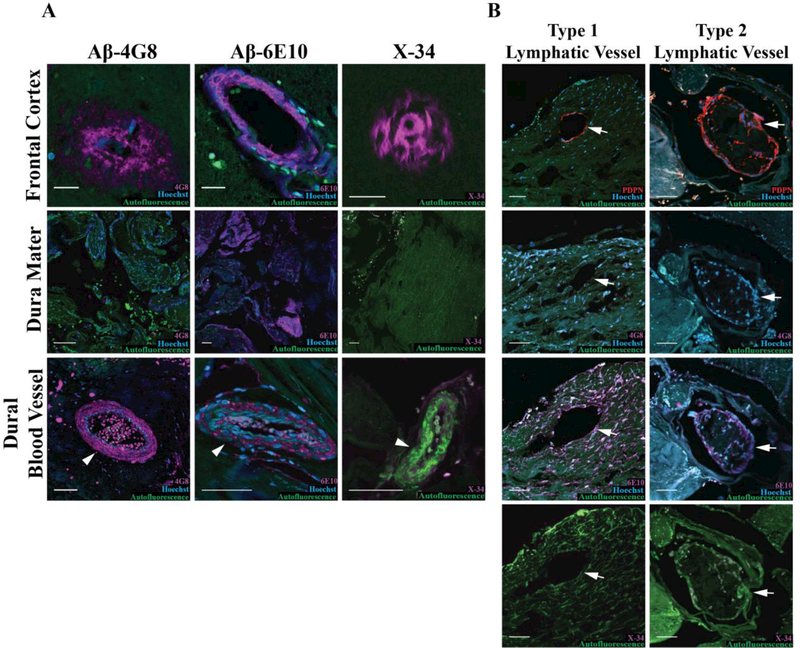

The deposition of Aβ in leptomeningeal and intraparenchymal cerebral arterial walls is a common feature among AD subjects that is thought to reflect the role of perivascular spaces as routes for efflux of Aβ from the brain parenchyma (Carare et al., 2008; Kalaria and Ballard, 1999; Weller et al., 2007). We hypothesized that if the meningeal lymphatic vasculature participates in clearance of Aβ, then Aβ deposition may also occur along the meningeal lymphatic vessels of AD subjects. To evaluate this hypothesis, we labeled sequential cortical and SSS sections with the 6E10 and 4G8 Aβ antibody clones, which display differential detection of prefibrillar oligomeric Aβ. Specifically, the 4G8 antibody binds to both fibrillar and prefibrillar oligomeric Aβ, while the 6E10 antibody only binds fibrillar Aβ (Kayed et al., 2007). As expected, Aβ immunoreactivity was largely absent from frontal cortical sections from control subjects while AD subjects exhibited dense frontal cortical Aβ immunoreactivity (Figure 2A, Figure 3A). In the dura mater, we observed that Aβ reactivity was clone-specific in both AD and control subjects, with widespread, diffuse immunoreactivity detected in the meninges by the anti-Aβ 6E10 clone, but scant reactivity with the anti-Aβ 4G8 clone (Figure 3A, Table 2). Several dural blood vessels also exhibited Aβ immunoreactivity, though more were found in sections labeled with the 6E10 clone than the 4G8 clone (Figure 3A). Interestingly, when staining with the 6E10 clone, we observed Aβ immunofluorescence in the walls of dural lymphatic vessels, with 3/6 AD and 0/5 control subjects exhibiting Aβ6E10+PDPN+ lymphatic vessels (Figure 3B, Table 2). However, labeling with the 4G8 antibody did not result in PDPN+ lymphatic vessel-associated immunoreactivity (Figure 3B, Table 2). As noted above, the 4G8 antibody readily labeled cortical Aβ plaques, leptomeningeal Aβ, and Aβ associated with dural arteries (Figure 2A, Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Dural lymphatic vasculature and meningeal Aβ immunoreactivity in AD subjects.

A. Detection of Aβ immunoreactivity with 6E10 and 4G8 clones, and Aβ aggregates with the congophilic X-34 dye in frontal cortex (top), within dural tissue (middle), and in meningeal blood vessels (bottom, arrowhead). B. Representative Type 1 (left) and Type 2 (right) lymphatic vessel (arrows). Sequential slices stained with PDPN, 6E10, 4G8 and X-34 shows that co-localization between PDPN and the 6E10 in some vessels. PDPN co-localization with 4G8 immunoreactivity or with X-34 labeling was not observed. Scale bars in frontal cortex micrographs represent 20 um and scale bars in other micrographs represent 50 μm.

Table 2.

Detailed results of amyloid beta reactivity and distribution in AD and control subjects. αSMA, Smooth muscle actin; N/A, Not applicable (no meningeal lymphatic vessels observed).

| Subject | 4G8+ Meningeal Blood Vessel (5 vessels per suject) | 6E10+ Meningeal Blood Vessel (5 vessels per subject) | 4G8+ Meningeal Lymphatic Vessel (2 vessels per subject) | 6E10+ Meningeal Lymphatic Vessel (2 vessels per subject) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

Because the 6E10 antibody only detects fibrillary species of Aβ, we surmised that if the immunoreactivity we observed with the 6E10 antibody was specific to Aβ, then similar patterns would be observed when staining with a congophilic dye such as Congo red or X-34. Importantly, there was no observable positive Congo red or X-34 labeling in meningeal sections of both control and AD subjects using this approach (Figure 3A-B). The lack of positive staining with both the 4G8 antibody and congophilic dyes argue that the anti-Aβ 6E10-immunoreactivity seen in dural tissue from control and AD subjects and in association with meningeal lymphatic vessels reflects non-specific antibody binding rather than the specific localization of Aβ to these structures.

4. Discussion

4.1. Confirmation of a lymphatic vessel network in the human meninges

Our observation of lymphatic vessels in the dura mater of 19/21 human subjects corroborates the recent report of lymphatic vessels in three human subjects by Absinta and colleagues (Absinta et al., 2017). Together, these reports confirm that the meningeal lymphatic system is conserved among rodents, non-human primates, and humans.

While the PDPN+LYVE1+CD31- (Type 1) lymphatic vessels identified in the present study are consistent with peripheral tissue lymphatic capillaries and those described in the murine SSS (Louveau et al., 2015), we also identify PDPN+LYVE1-CD31- (Type 2) dural vessels. In mice, LYVE1 is heterogeneously expressed along the lymphatic hierarchy with progressive loss of expression in precollectors and collecting vessels. Thus, the Type 2 vessels we observe may represent a precollector (PDPN+LYVE1-αSMA-) rather than capillary phenotype. Alternatively, inflammation can induce internalization and degradation of LYVE1, which may contribute to the discrepancy observed between naïve murine and post mortem human tissue (Johnson et al., 2007). As inflammatory cells are inconspicuous in both AD and control dura, this possibility seems less likely. Finally, though our data reveals that these structures lack staining for CD31 and are therefore not meningeal blood vessels, it is possible that these Type 2 structures lined with PDPN+ cells are also non-lymphatic. Future studies in non-human primate or human dura mater should consider orthogonal approaches such as flow sorting coupled with quantitative PCR to provide greater insight into the identity of these putative lymphatic vessels.

Our findings also highlight other differences between the human and rodent meningeal lymphatic system. In the murine meninges, the superior sagittal sinus is typically flanked by two lymphatic capillaries, whereas in the human subjects within our study, we noted >5 vessels in subjects that had identifiable lymphatic vessels associated with this considerably larger structure. Furthermore, murine meningeal lymphatic vessels typically display a measured diameter of 20–30 μm (Aspelund et al., 2015; Louveau et al., 2015), whereas the calculated diameter range of human meningeal lymphatic vessels in our study varied widely from 19–470 μm. These findings corroborate the wide diameter range reported by Absinta and colleagues (Absinta et al., 2017). These differences, as well as the anatomical distribution of Type 1 and Type 2 vessels may have functional significance; dural Type 1 vessels may absorb the interstitial fluid within the dura itself while Type 2 vessels, although apparently lacking contractile mural cells, may conduct CNS- and dura-derived lymph towards the cervical lymphatic drainage. These possibilities are clearly speculative, and further functional studies will be necessary to evaluate them.

4.2. Absence of Aβ deposition in the meninges, meningeal blood vessels, and meningeal lymphatic vessels

The dura mater and several identified dural lymphatic vessels displayed diffuse immunoreactivity when stained with the 6E10 clone, but this pattern was not observed when staining with the 4G8 antibody clone. This was unexpected because the 4G8 antibody identifies a broader range of Aβ species, binding both prefibrillar Aβ oligomers and fibrillary Aβ, whereas the 6E10 antibody only binds fibrillary Aβ (Kayed et al., 2007). Despite the fact that these antibodies bind to different epitopes on the extracellular domain of the Aβ protein (Aho et al., 2010), the staining patterns of dense-core Aβ plaques that contain fibrillary Aβ are relatively similar (Liu et al., 2015; Rak et al., 2007). To determine if the 6E10 immunoreactivity was fibrillary Aβ or nonspecific, we stained dural samples both Congo Red and X-34, which detect fibrillary Aβ in an antibody-independent manner, were also negative. Taken with our observation that the dura mater of 4/5 control subjects displayed diffuse immunoreactivity with the 6E10 antibody, these findings suggest that Aβ is not deposited in the dura and that the 6E10-positive labeling was likely non-specific.

These findings suggest that although interstitial Aβ exchanges into the CSF compartment, it does not appear to appreciably deposit within or along meningeal lymphatic vessels associated with the SSS. This does not necessarily indicate that these lymphatic vessels do not participate in the clearance of soluble Aβ from brain tissue, but rather may simply reflect the fact that Aβ does not specifically deposit along these structures. The relative absence of mural cells investing the meningeal lymphatic vasculature or differences in the physical (such as pulsation) or chemical environment (such as vessel wall matrix composition) of the lymphatic versus arterial wall may prevent Aβ associated with these vessels from aggregating as it does in the wall of leptomeningeal or intraparenchymal arteries. Indeed, it has recently been suggested that the unique chemical and shear environment within the cerebral arterial wall may underlie the Aβ deposition that is characteristic of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (Trumbore, 2016). Furthermore, tracer studies carried out in experimental animals and human subjects suggest that solutes in the CSF are transported along perineural routes through the basal cisterns and through the cribriform plate (Bedussi et al., 2017; Johnston et al., 2004). Thus meningeal lymphatic vessels in the calvarium may play only a minor role in Aβ clearance from the CSF, compared to those at the base of the skull.

4.3. Study Limitations

The use of the spectral unmixing approach was critical to defining small PDPN+ lymphatic vessels in the highly autofluorescent human meninges. Despite this, we still observed some nonspecific staining, which was attributable to secondary antibody binding. This issue is common to immunofluorescence in post mortem human tissue, highlighting the importance of using strategies to overcome endogenous tissue autofluorescence, and for the use of approaches to evaluate meningeal lymphatic function that are orthogonal to microscopy.

Although this is the largest human cohort evaluated for meningeal lymphatic vessels, another limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size and narrow anatomical focus, including SSS tissue from 21 subjects, 6 of which were diagnosed with AD and 5 of which were control subjects. Since the concentration of Aβ in the CSF and brain vary with the stage of AD, this may affect the detection of Aβ in the dura mater. Future studies will benefit from including a larger number of subjects with a wide range of CERAD scores, allowing subjects to be stratified by stage of AD. Additionally, the use of ELISA-based assessment of Aβ from fresh-frozen meningeal tissues may provide a more sensitive readout for Aβ burden in this compartment in aging or AD. In this way, potential AD stage-associated changes in lymphatic vessel-Aβ association could be more comprehensively defined.

This study was further limited by the general scarcity of post mortem meningeal tissue and the time-intensive use of spectral unmixing in large tissue sections in order to detect small vessels within an intensely autofluorescent tissue. It is possible that changes in lymphatic vessel abundance, structure, and association with Aβ may vary in different meningeal compartments, thus the findings that we report may not generalizable to the wider meningeal lymphatic vasculature. In future studies, it will be important to characterize meningeal lymphatic vessels from other dural sinus structures (such as the transverse and straight sinuses) and meninges in the skull base, including those associated with cranial nerves.

5. Conclusions

Together, these findings confirm the presence of meningeal lymphatic vasculature in humans and provide insight into two possible populations of lymphatic vessels in the meninges: one with traditional characteristics of lymphatic vessel morphology and another with atypical morphology. We also report the absence of Aβ deposition in the wall of dural lymphatic vessels and that the use of multiple approaches is critical for accurate detection of Aβ in meningeal tissue. These findings suggest that although the meningeal lymphatic vessels in the calvarium may contribute to the clearance of interstitial solutes including Aβ from the brain parenchyma, Aβ does not appear to deposit in these potential efflux pathways in the same manner that it does along peri-arterial pathways in the setting of cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

Highlights.

Dural sinus-associated lymphatic vessels were observed in 19/21 human post mortem samples.

No differences in vessel number or diameter were observed between control and Alzheimer’s subjects.

Amyloid β deposition was not observed along lymphatic vessels in control or Alzheimer’s disease subjects.

Acknowledgements

We thank Stefanie Kaech-Petrie and Crystal Chaw at the OHSU Advanced Light Microscopy Core for their technical expertise and assistance with spectral unmixing. We also thank David Clark for his assistance in preparing meningeal tissue sections. This project was supported by the NIA (AG054456, JJI), NINDS (NS089709, JJI), the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation (JJI), NIA (F30AG060681, JRG); an Alzheimer’s Disease Center Grant (AG008017, Kaye PI) that supported longitudinal follow-up and subsequent brain autopsies providing the human brain samples used in this study; an NINDS P30 grant (NS061800; Aicher PI) supported fluorescencebased microscopy in the present study.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Absinta M, Ha S-K, Nair G, Sati P, Luciano NJ, Palisoc M, Louveau A, Zaghloul KA, Pittaluga S, Kipnis J, Reich DS, 2017. Human and nonhuman primate meninges harbor lymphatic vessels that can be visualized noninvasively by MRI. Elife 6, e29738 10.7554/eLife.29738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aho L, Pikkarainen M, Hiltunen M, Leinonen V, Alafuzoff I, 2010. Immunohistochemical Visualization of Amyloid-β Protein Precursor and Amyloid-β in Extra- and Intracellular Compartments in the Human Brain. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 20, 1015–1028. 10.3233/JAD-2010-091681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspelund a., Antila S, Proulx ST, Karlsen TV, Karaman S, Detmar M, Wiig H, Alitalo K, 2015. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J. Exp. Med 212, 991–9. 10.1084/jem.20142290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedussi B, Naessens DMP, de Vos J, Olde Engberink R, Wilhelmus MMM, Richard E, ten Hove M, vanBavel E, Bakker ENTP, 2017. Enhanced interstitial fluid drainage in the hippocampus of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Sci. Rep 7, 744 10.1038/s41598-017-00861-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton M, Flessner M, Armstrong D, Mohamed R, Hay J, Johnston M, 1999. Contribution of extracranial lymphatics and arachnoid villi to the clearance of a CSF tracer in the rat. Am. J. Physiol 276, R818–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E, 1995. Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol. Aging 16, 271–8-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury MW, Cole DF, 1980. The role of the lymphatic system in drainage of cerebrospinal fluid and aqueous humour. J. Physiol 299, 353–365. 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carare RO, Bernardes-Silva M, Newman TA, Page AM, Nicoll JAR, Perry VH, Weller RO, 2008. Solutes, but not cells, drain from the brain parenchyma along basement membranes of capillaries and arteries: significance for cerebral amyloid angiopathy and neuroimmunology. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol 34, 131–144. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00926.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserr HF, Harling-Berg CJ, Knopf PM, 1992. Drainage of brain extracellular fluid into blood and deep cervical lymph and its immunological significance. Brain Pathol. 2, 269–76. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1992.tb00703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erten-Lyons D, Woltjer R, Kaye J, Mattek N, Dodge HH, Green S, Tran H, Howieson DB, Wild K, Silbert LC, 2013. Neuropathologic basis of white matter hyperintensity accumulation with advanced age. Neurology 81, 977–83. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a43e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabe CC, 2005. Amyloid Accumulation and Pathogensis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Significance of Monomeric, Oligomeric and Fibrillar Aβ, in: Alzheimer’s Disease. Springer US, pp. 167–177. 10.1007/0-387-23226-5_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M, 2015. Implications of the discovery of brain lymphatic pathways. Lancet Neurol. 14, 977–979. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00221-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, Benveniste H, Vates GE, Deane R, Goldman SA, Nagelhus EA, Nedergaard M, 2012. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid. Sci. Transl. Med 4 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LA, Prevo R, Clasper S, Jackson DG, 2007. Inflammation-induced uptake and degradation of the lymphatic endothelial hyaluronan receptor LYVE-1. J. Biol. Chem 282, 33671–33680. 10.1074/jbc.M702889200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M, Zakharov A, Papaiconomou C, Salmasi G, Armstrong D, 2004. Evidence of connections between cerebrospinal fluid and nasal lymphatic vessels in humans, non-human primates and other mammalian species. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res 1, 2 10.1186/1743-8454-1-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaria RN, Ballard C, 1999. Overlap between pathology of Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord 10.1097/00002093-199912003-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, Sarsoza F, Saing T, Cotman CW, Necula M, Margol L, Wu J, Breydo L, Thompson JL, Rasool S, Gurlo T, Butler P, Glabe CG, 2007. Fibril specific, conformation dependent antibodies recognize a generic epitope common to amyloid fibrils and fibrillar oligomers that is absent in prefibrillar oligomers. Mol. Neurodegener 2, 18 10.1186/1750-1326-2-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Paulson JB, Forster CL, Shapiro SL, Ashe KH, Zahs KR, 2015. Characterization of a Novel Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease—Amyloid Pathology and Unique β-Amyloid Oligomer Profile. PLoS One 10, e0126317 10.1371/journal.pone.0126317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louveau A, Plog BA, Antila S, Alitalo K, Nedergaard M, Kipnis J, 2017. Understanding the functions and relationships of the glymphatic system and meningeal lymphatics. J. Clin. Invest 127, 3210–3219. 10.1172/JCI90603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, Eccles JD, Rouhani SJ, Peske JD, Derecki NC, Castle D, Mandell JW, Lee KS, Harris TH, Kipnis J, 2015. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 523, 337–341. 10.1038/nature14432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, Munsell L, Kasten T, Morris JC, Yarasheski KE, Bateman RJ, 2010. Decreased Clearance of CNS -Amyloid in Alzheimer’s Disease. Science (80-. ). 330, 1774–1774. 10.1126/science.1197623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Berg L, 1991. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 41, 479–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson BW, Elbert DL, Mawuenyega KG, Kasten T, Ovod V, Ma S, Xiong C, Chott R, Yarasheski K, Sigurdson W, Zhang L, Goate A, Benzinger T, Morris JC, Holtzman D, Bateman RJ, 2015. Age and amyloid effects on human central nervous system amyloid-beta kinetics. Ann. Neurol 78, 439–453. 10.1002/ana.24454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rak M, Del Bigio MR, Mai S, Westaway D, Gough K, 2007. Dense-core and diffuse Aβ plaques in TgCRND8 mice studied with synchrotron FTIR microspectroscopy. Biopolymers 87, 207–217. 10.1002/bip.20820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan A, Nelson AR, Sagare AP, Zlokovic B V, 2015 Impaired vascular-mediated clearance of brain amyloid beta in Alzheimer’s disease: the role, regulation and restoration of LRP1. Front. Aging Neurosci 7, 136 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ, 2001. Alzheimer’s disease results from the cerebral accumulation and cytotoxicity of amyloid beta-protein. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 3, 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styren SD, Hamilton RL, Styren GC, Klunk WE, 2000. X-34, A Fluorescent Derivative of Congo Red: A Novel Histochemical Stain for Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology. J. Histochem. Cytochem 48, 1223–1232. 10.1177/002215540004800906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, Glodzik L, Butler T, Fieremans E, Axel L, Rusinek H, Nicholson C, Zlokovic BV, Frangione B, Blennow K, Ménard J, Zetterberg H, Wisniewski T, de Leon MJ, 2015. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11, 457–70. 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trumbore CN, 2016. Shear-Induced Amyloid Formation in the Brain: I. Potential Vascular and Parenchymal Processes. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 54, 457–470. 10.3233/JAD-160027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller RO, Subash M, Preston SD, Mazanti I, Carare RO, 2007. SYMPOSIUM: Clearance of Aβ from the Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease: Perivascular Drainage of Amyloid-β Peptides from the Brain and Its Failure in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Pathol 18, 253–266. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00133.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]