Abstract

Context:

Smartphone use is being investigated as a potential behavioral addiction. Most of the studies opt for a subjective questionnaire-based method. This study evaluates the psychological correlates of excessive smartphone use. It uses a telemetric approach to quantitatively and objectively measure participants' smartphone use.

Methodology:

One hundred forty consenting undergraduate and postgraduate students using an Android smartphone at a tertiary care teaching hospital were recruited by serial sampling. They were pre-tested with the Smartphone Addiction Scale-Short Version, Big five inventory, Levenson's Locus of Control Scale, Ego Resiliency Scale, Perceived Stress Scale, and Materialism Values Scale. Participants' smartphones were installed with tracker apps, which kept track of total smartphone usage and time spent on individual apps, number of lock–unlock cycles, and total screen time. Data from tracker apps were recorded after 7 days.

Results:

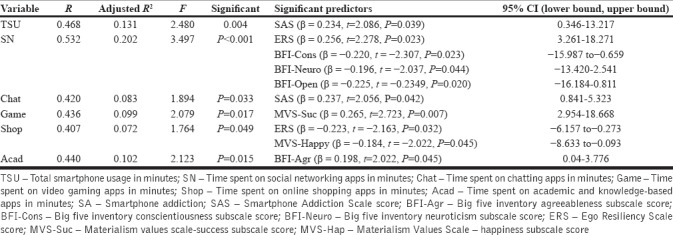

About 36 % of participants fulfilled smartphone addiction criteria. Smartphone Addiction Scale score significantly predicted time spent on a smartphone in the 7-day period (β = 0.234, t = 2.086, P = 0.039). Predictors for time spent on social networking sites were ego resiliency (β = 0.256, t = 2.278, P = 0.008), conscientiousness (β = −0.220, t = −2.307, P = 0.023), neuroticism (β = −0.196, t = −2.037, P = 0.044), and openness (β = −0.225, t = −2.349, P = 0.020). Time spent gaming was predicted by success domain of materialism (β =0.265, t = 2.723, P = 0.007) and shopping by ego resiliency and happiness domain of materialism.

Conclusions:

Telemetric approach is a sound, objective method for evaluating smartphone use. Psychological factors predict overall smartphone usage as well as usage of individual apps. Smartphone Addiction Scale scores correlate with and predict overall smartphone usage.

Key words: Excessive use, predictors, psychological, smartphone, telemetry

INTRODUCTION

Smartphones are part-and-parcel of our life. They are handy tools for communication, offer easy access to the Internet and media, and are highly personalizable with different wallpapers, fonts, themes, languages, and even operating systems.[1]

There are >950 million smartphone users in India alone. The number of smartphone users is growing with geometric progression and have left landline users far behind in the last 5 years.[2,3]

Why smartphones have become so popular?

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is the theoretical construct which explains why and how humans accept a new technology in their life.[4] This model has explained the adaptation of personal computers and Internet-based phones in the past.[5,6,7] The TAM states that 1) how useful do we perceive a technology (perceived usefulness; PU), 2) how easy do we perceive using that technology (perceived ease of use; PEOU), and 3) the reasons behind selecting that technology for use predict an easy adaptation of a technology. Smartphones, being lightweight, trendy, multi-functional, portable, customizable, and user-friendly, are obvious contenders for a higher PU and PEOU compared to other gadgets.[8]

Excessive smartphone use and addiction

There are multiple reports of smartphone overuse in the scientific literature. For instance, in the USA alone, ownership of smartphones has risen by 76% in undergraduate students.[9] Another USA-based study estimated that a student spends 3.5 or more hours on his or her smartphone every day for entertainment and chatting.[10] An Africa-based study showed that excessive use of the smartphone in graduate students was associated with excessive procrastination, distraction, poor academic scores, and worsened grammatical and linguistic accuracy.[11] Smartphone users also report feelings of extreme anxiety and cognitive delays on separation from their smartphones.[12] This compulsive nature of checking smartphones frequently caused researchers to wonder whether smartphone use is a behavioral addiction!

Researchers have evaluated individuals' subjective smartphone usage and reported prevalence of smartphone addiction ranging from 8.7% in Korea to 32% in India.[13,14]

An Indian study adapted the criteria for substance dependence to smartphone use and showed that 40% of postgraduate residents using a smartphone fulfilled the criteria for smartphone dependence.[15] Similar to other addictions (substance and behavioral), excessive and addictive smartphone use has been linked to life stress, lower self-efficacy, higher perceived stress, high internal locus of control, materialism, and Internet addiction. Big five personality traits have been linked to usage of various apps on the smartphone.[16,17,18,19,20,21,22]

The need for this study was the fact that most of the evidence on this topic is based on self-reported, subjective questionnaires.[16,17,18,19,20,21] It is noteworthy that most of the studies are from Korea, China, and the west with scarce Indian literature.[14,15,23] Psychological factors, in addition to biological and environmental factors, have predictive value in behavioral addictions.[24,25] This study was therefore designed to evaluate psychological correlates and predictors of excessive smartphone use with a telemetric approach, which is a more objective method for measuring one's smartphone use.

METHODOLOGY

Site

The study was conducted in the Psychiatry Department of a tertiary care teaching hospital in western India in an urban setting. The Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained. Written informed consent was taken from all participants.

Sample

All consenting undergraduate and postgraduate students using an Android operating system-based smartphone were recruited for the study. Students (1) with a history of any neuropsychiatric disorder, (2) having two or more smartphones, (3) owning a tablet device, and/or (4) having failed to complete both the phases of the study were excluded.

Procedure

Phase I – Participants were evaluated using the following materials.

Clinical datasheet

This was a self-designed, semi-structured proforma, which was used to gather sociodemographic data. The questionnaire also asked participants to provide information regarding their smartphone usage such as the number of hours spent every day on a smartphone, amount spent on monthly Internet pack, and so on.

Big five inventory

This is a 44-item inventory that measures an individual on five factors (dimensions) of personality; namely extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness.[26,27] Participants rated to what extent does each question apply to them, on a 5-level Likert scale. The scoring system includes reverse scoring questions. The big five inventory (BFI) has been used extensively with good psychometric properties across cultures.[28]

Materialism Value Scale

The Materialism Value Scale (MVS) explores materialism as a value that influences people to interpret their lives.[29] It measures the importance attributed to possession and/or acquisition of material goods in achieving major life goals or desired states. The MVS evaluates three domains of materialism: (1) Success – how much an individual uses material objects to judge success of others or oneself, (2) Centrality – the centrality of material values in an individual's life, and (3) Happiness – the extent of the belief that possession and acquisition of material goods leads to happiness and life satisfaction. We used the revised, 15-item short version of the MVS, as it has demonstrated better psychometric properties.[30]

Perceived Stress Scale

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) is perhaps the most widely used instrument for measuring the perception of stress.[31] It is a 10-item, 5-level Likert scale. It measures to what extent does an individual feel stressed. There are five negatively worded questions with reverse scoring instructions. The score can range from 0 to 40, and a higher score indicates higher perceived stress. Although PSS is available with lesser items, psychometric properties were found superior with the 10-item version, which was used in this study.[32]

Ego Resilience Scale

“Resilience” is the ability to bounce back/recover from or adapt to stress. We used Ego Resilience Scale (ERS) to measure this trait.[33] It is a 14-item, 4-level Likert scale, where subjects indicate how much each item applies to them. Scores range from 14 to 56 and subjects can be grouped into very high resiliency trait (score 47–56), high resiliency trait (score 35–46) undetermined trait (score 23–34), low resiliency trait (11–22), and very low resiliency trait (score 0–10). ERS has shown good psychometric properties and temporal stability.[34,35]

Levenson's Locus of Control Scale

Locus of control refers to an individual's perceptions about the cause of events and his/her control on those events in his/her life. The Levenson's Locus of Control (LLOC) scale is a 6-level Likert scale and includes 24 items.[36] It evaluates an individual's locus of control across three domains, whether the individual believes the events in his/her life to be controlled by him/herself (internal locus of control), powerful others/external agencies (external locus of control), and chance/luck (chance locus of control). The scale is a modified version of the Rotter's I–E scale (which had only the internal and external subscales) and has a Cronbach's alpha value 0.68. The instrument has been utilized in multiple projects with good consistency and validity.

Smartphone Addiction Scale

The Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS) is a 33-item questionnaire for assessment of an individual's subjectively perceived smartphone usage patterns.[37] It evaluates the addictiveness of one's smartphone usage across six dimensions, namely (1) daily life disturbance, (2) positive anticipation, (3) withdrawal, (4) cyber-space orientated relationship, (5) overuse, and (6) tolerance – inability to control one's smartphone usage despite efforts. The SAS showed high psychometric properties (Cronbach's alpha 0.96) and has been used extensively.[38,39] Kwon et al. also developed a shorter version of SAS (SAS-SV), which includes 10 items from the 33 included in the original SAS.[40] This instrument has cut-off scores (31 for males and 33 for females) for diagnosing smartphone addiction. We used in this study, (1) cumulative SAS score (from 33-item version), since it offered a more comprehensive picture of an individual's smartphone use and (2) SAS-SV score (from 10-item version) as it offered a cut-off value with which we could conduct a sub-group analysis of smartphone use pattern between those who scored above and below the cut-off scores.

On completion of this assessment, participants entered the Phase II. This consisted of making the following changes in the participants' Android smartphones.

Phase II: The study was conducted at a time when no important events (examinations, cultural/sports festival) were scheduled.

Installing the Google play store-based free app “Callistics©”

Callistics is an Android-based app available for free download from the Google play store. It is developed by the Mobilesoft r.s.o. Once downloaded, it keeps track of the number and duration of calls made and received from the Android device. It, however, does not keep track of any content from the calls.

Installing the Google play store-based free app “App Usage Tracker©”

App Usage Tracker (AUT) is a free app available on the Google play store for Android smartphones. It can be downloaded and used without any fees or permission. This app keeps track of the duration in minutes spent on all the apps by the smartphone user. The duration is recorded in minutes and seconds and is accurate to a 5-second margin. AUT does not keep track of any personal communication or media exchange, nor does it share the tracked data without the user's permission. We used AUT data on all individual apps, system apps, and a combined total smartphone usage in minutes over 7 days.

Installing the Google play store-based free app “Instant©”

Instant is a free app available on the Google play store for Android smartphones. It can be downloaded and used without any fees or permission. It keeps track of the duration in minutes spent on all the apps by the smartphone user. The duration is recorded in minutes and seconds and is accurate to a 5-second margin. It also provides the number of lock–unlock cycle an individual has performed on his smartphone over a stipulated time-frame. Instant does not keep track of any personal communication or media exchange, nor does it share the tracked data without the user's permission.

Participants were shown the workings of the three apps and were assured that their data would not be deleted or shared. Participants were advised to continue using their smartphone in a regular manner and were advised to follow-up after 7 days. During follow-up, readings from the “Callistics©”, “Instant©”, and “App Usage Tracker©” were recorded. Participants were then advised to uninstall the tracker apps if they wished.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, t-test, and Mann–Whitney U test to evaluate and compare demographic variables and quantitative data. We used Pearson's correlation to assess the relationship between smartphone usage patterns and scores on scales for measurement of psychological variables. Backward stepwise multivariate regression was used to evaluate predictors of problematic smartphone use. Statistical significance was assumed at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Sample

Initially, 163 participants were recruited, of which 23 dropped out after Phase I. The remaining sample of 140 (70 males and 70 females) consisted of interns (34, 24.3%), postgraduate residents (34, 24.3%), and undergraduate medical students in second year of MBBS (40, 28.5%) and third year of MBBS (32, 23%). Mean age of the sample was 22.89 ± 2.79 years.

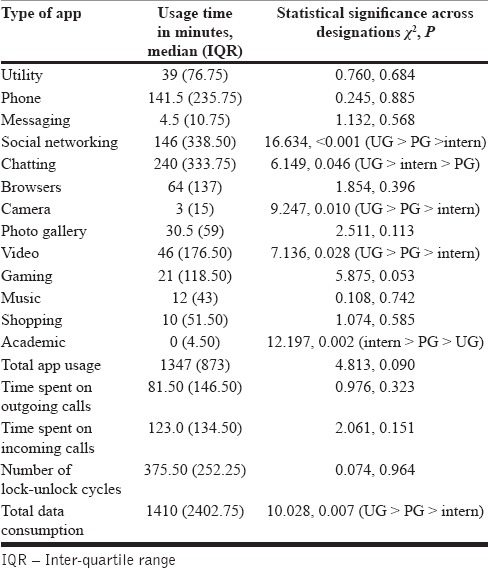

Smartphone usage practices

Data from the App Usage Tracker [Table 1] showed that females were using the camera (Z = −3.110, P = 0.002) and the photo gallery (Z = −2.251, P = 0.024) for a significantly longer duration than males. Females also spent significantly longer duration on incoming (Z = −2.920, P = 0.004) as well as outgoing calls (Z = −2.019, P = 0.043) than males. Males were using the online video streaming apps (Z = −2.289, P = 0.05) and smartphone-based academic apps (Z = −2.065, P =0.039) for a significantly longer duration than females. Males also consumed significantly more data on their smartphones than women (2130 vs 939 Mb, Z = −4.101, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Smartphone usage preferences and practices

Smartphone Addiction Scale scores

The SAS scores did not differ significantly between genders. About 36.4% (51/140) students fulfilled the SAS-SV cut-off for smartphone addiction. Prevalence of smartphone addiction did not differ significantly between genders (χ2 = 0.278, P = 0.363) or designations (χ2 = 0.327, P = 0.849). Participants with smartphone addiction spent significantly more time on their smartphone (Z = −2.022, P = 0.043) and performed significantly more number of lock–unlock cycles (Z = −2.215, P = 0.027) in the 7-day period.

Psychological variables and SAS scores

The multiple regression model [R2 = 0.446, F(13,125) = 9.557, P < 0.001] showed the scores on PSS [β = 0.282, t = 3.618, P < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI): (0.669, 2.285)], BFI-agreeableness [β = 0.152, t = 2.011, P = 0.046, 95% CI: (0.012, 1.462)], BFI-conscientiousness [β = −0.295, t = −3.931, P < 0.001, 95% CI: (−1.850, −0.611)], BFI-neuroticism [β = −0.165, t = −2.099, P = 0.038, 95% CI: (−1.385, −0.041)], LOC-internal [β = −0.328, t = −4.009, P < 0.001, 95% CI: (−1.219, −0.413)], and LOC-external [β =0.514, t = 5.497, P < 0.001, 95% CI: (0.770, 1.637)] as significant predictors for SAS scores.

Psychological variables and objectively measured smartphone use

Time spent on smartphone in 7-days correlated significantly with scores on SAS (r = 0.369, P < 0.001), PSS (r = 0.178, P = 0.035), BFI-conscience (r = −0.259, P = 0.002), and LOC-external (r = 0.256, P = 0.002). Total screen time (r = 0.231, P = 0.006) and lock–unlock cycles (r = 0.254, P = 0.002) correlated significantly with SAS scores. Time spent using shopping apps correlated with ERS (r = −0.214, P = 0.011) and BFI-extra (r = −0.214, P = 0.013). Time spent gaming correlated with score on MVS-success (r = 0.235, P = 0.005). Time spent on camera apps correlated negatively with BFI-agreeableness (r = −0.219, P = 0.019). Social networking apps correlated positively with score on PSS (r = 0.201, P = 0.018) and negatively with score on BFI-agreeableness (r = −0.228, P = 0.007), BFI-conscientiousness (r = −0.259, P = 0.002), and BFI-openness (r = −0.174, P = −0.040).

Multivariate regression analyses were performed using time spent on smartphone in 7-days as a dependent variable and scores on various psychometric tools as independent variables [Table 2].

Table 2.

Multivariate regression analysis showing time spent on various smartphone apps and their significant predictors

DISCUSSION

This study explores the possible role of psychological variables in predicting excessive smartphone use among medical students. Self-rated questionnaire-based studies on smartphone usage have implied that smartphone usage can be excessive and even addictive. Smartphones are constantly present around us, and it is very difficult to accurately and objectively recall one's own smartphone usage in a retrospective manner.[41] We attempted to eliminate subjectivity and recall errors in assessing smartphone usage by employing an objective, telemetric method.

The first important finding in this study was the prevalence of “smartphone addiction” and the predictive value of SAS. SAS scores also emerged as the sole predictor for the global smartphone usage in a 7-day period. Our sample showed 35% participants scoring above the cut-off score on SAS-SV for smartphone addiction. This supports the existing Indian literature on the topic.[14,15] This, however, needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. Till date, studies evaluating smartphone addiction have explored problematic smartphone usage with self-report questionnaires,[42,44] adopted the substance dependence criteria for tolerance and withdrawal to smartphone usage,[45,46] and explored the impulse control dimension of excessive smartphone use.[47,48] These approaches, however, could not establish a robust neurobiological or psychopathological model for smartphone addiction as a separate diagnostic entity.[49] It is also worth noticing that, unlike substances such as alcohol or cannabis, many features in a smartphone (such as making and receiving calls) are a part-and-parcel of daily life, and not a luxury or a source of pleasure. These factors need to be considered and controlled for in future research for exploring this issue in detail. Summing up, SAS may be of value in determining the quantitative aspect of an individual's smartphone use. It needs to be explored whether that usage amounts to a behavioral addiction.

Coming to predictors of usage of individual apps, agreeableness was identified as a predictor for usage of academic apps. Agreeableness includes courteousness, trust, tolerance, and will to help others. Tolerance and forgiving characteristics make agreeable individuals more willing to accept new challenges and technologies as well as spend more time online.[50] Agreeable individuals have also been shown to be more persistent in investigating difficult content and user-unfriendly online data.[51] Academic apps contain scientific jargon, graphs, and statistics and are tedious to navigate through. They contain various tables, classifications and sub-classifications, and a lot of text, which may be difficult to read on a handheld small screen. Therefore, individuals with patience and tolerance, therefore agreeableness, are more likely to use such apps.

Predictors for high social networking apps usage were low ego resiliency, low conscientiousness, low neuroticism, and low openness. Conscientiousness, in earlier studies, has been negatively correlated with a higher preference toward apps involving leisure and creativity.[51,52,53] Studies have also shown a negative correlation between conscientiousness and adaptation of social apps Facebook and Twitter.[54,55] Reason for the negative impact of conscientiousness on social media could be the fact that, conscientious people are focused and organized and possess high self-control and therefore may show less inclination to engage in leisurely activities. Coming to the link between neuroticism and preference for social networking apps, the literature has mixed results. Early evidence showed a negative correlation between neuroticism and preference for social networking,[56] possibly due to high levels of neuroticism causing individuals to perceive new technology as threatening or stressful.[50] The recent trend, however, points toward a positive correlation between them.[55]

We also observed low scores on openness to new experiences as a predictor for longer time spent on social networking apps. It was expected that individuals with high openness would be more adaptive toward newer technologies and therefore would spend more time on smart phones.[57] A number of explanations have been offered by other investigators who too observed this discrepancy.[51,58,59] Individuals with high openness to experience, though are enthusiastic to try new things, may perceive social media and networks too restrictive a medium for their taste, or may not find them useful to their need.[58,60] It is hypothesized that, once a technology becomes mainstream, its popularity may compensate for the initial preference shown by individuals with high openness to experience.

Lower ego resiliency predicted more time spent on online shopping. Ego resiliency is a key construct for understanding motivation and behavior. Ego resiliency modifies one's level of control (ego control) in response to situations and stimuli.[61]

High ego resiliency and ego control have been identified as protective factors against impulsive behaviors and substance dependence, and therefore might be implicated in online shopping as well.[62]

Higher materialism, particularly the success subscale scores, correlated with and predicted longer duration spent gaming. Playing games involves chasing a target to achieve a reward, either monitory or emotional. Individuals with high materialism regard material possessions highly as a source of happiness and success. Materialism is also correlated strongly with motivation and therefore implicated in the excessive use of the Internet and cell phones, online gaming, and compulsive online buying.[20,63,64]

This article adds evidence to the existing literature by objectively evaluating smartphone usage practices. It addresses one important limitation in research concerning behavioral aspects of smartphones and social media use: It shows the ease of administration and plausibility of using telemetric services in objectively measuring smartphone usage. Future research with more focus on psychological predictors of problematic smartphone use will be beneficial. Screening in children and adolescents for some of these psychological variables may prove to be helpful in identifying the vulnerable population.

Limitations

The small sample size is an important limitation to the study. Reasons for a small sample were, (1) exclusion of students owning a smartphone based on Windows or iOS which eliminated a sizable sample, (2) unwillingness of many students to install apps to track one's smartphone use and to re-set the WhatsApp usage statistics. We also excluded students owning two smartphones and those using a tablet device. This limited the sample size and smartphone usage in those individuals could not be tested. A study involving a larger sample and multiple devices may yield different results. The sample being solely from a medical college may limit the generalizability of our findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Telemetric approach is a sound and practically viable method to objectively measure smartphone usage practices for research purposes. Psychological factors such as personality traits, materialism, and ego resiliency can be linked to the higher use of social networking apps, gaming apps, and online shopping apps, respectively. Further research in this domain is necessary.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cromer S. Smartphone in the US: A Market Analysis. [Last accessed on May 20, 2017]. Available from: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/18484/Cromar,%20Scott%20%20U.S.%20Smartphone%20Market%20Report.pdf .

- 2.Mogg T. Smartphone Sales Exceed those of PC's for the First Time. Apple Smashes Record. 2012. [Last accessed on May 20, 2017]. Available from: http:// www.digitaltrends.com/mobile/smartphone-salesexceed-those-of-pcs-for-first-time-applesmashes-record/

- 3.Telecom Regulatory Authority of India. Telecom Subscription Data as on 30th April, 2016. Ministry of Telecommunication. Government of India. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagozzi RP. The legacy of the technology acceptance model and a proposal for a paradigm shift. J Assoc Inf Syst. 2007;8:244–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkatesh V, Brown SA. A longitudinal investigation of personal computers in homes: Adoption determinants and emerging challenges. Manag Inf Syst Q. 2001;25:71–102. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park N. Adoption and use of computer-based voice over Internet protocol phone service: Toward an integrated model. J Communication. 2010;60:40–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park N, Lee KM, Cheong PH. University instructors' acceptance of electronic courseware: An application of the technology acceptance model. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2007;13:163–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elogie AA. Factors influencing the adoption of smartphones among undergraduate students in Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Nigeria. Libr Philos e J 2015. Paper 1257. [Last accessed on May 18, 2017]. Available from: http://www.digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1257 .

- 9.Smith A. US smartphone Use in 2015. Pew Research Center. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clayton RB, Leshner G, Almond A. The extended iSelf: The impact of iPhone separation on cognition, emotion and physiology. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2015;20:119–35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeboah J, Ewur GD. The impact of Whatsapp messenger usage on students performance in tertiary institutions in Ghana. J Educ Pract. 2014;5:157–64. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheever NA, Rosen LD, Carrier LM, Chavez A. Out of sight is not out of mind: The impact of restricting wireless mobile device use on anxiety levels among low, moderate and high users. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;37:290–97. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park N, Lee H. Nature of youth smartphone addiction in North Korea: Diverse dimensions of smartphone use and individual traits. J Commun Res. 2014;51:100–132. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikhita CS, Jadhav PR, Ajinkya SA. Prevalence of mobile phone dependence in secondary school adolescents. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:VC06–9. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/14396.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aggrawal M, Grover S, Basu D. Mobile phone use by resident doctors: Tendency to addiction-like behavior. German J Psychiatry. 2012;15:50–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu SI. The relationship between life stresses and smartphone addiction on Taiwanese university students: A mediation model of learning self-efficacy and social self-efficacy. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;34:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang JL, Wang HZ, Gaskin J, Wang LH. The role of stress and motivation in problematic smartphone use among college students. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;53:81–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samaha M, Hawi NS. Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance and satisfaction with life. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;57:321–25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park N, Kim YC, Shon HY, Shim H. Factors influencing smartphone use and dependency in South Korea. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29:1763–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YK, Chang CT, Lin Y, Cheng ZH. The dark side of smartphone usage: psychological traits, compulsive behavior and techno stress. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;31:373–83. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma A, Sahu R, Kasar PK, Sharma R. Internet addiction among professional courses students: A study from central India. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2014;3:1069–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chittaranjan G, Blom J, Gatica-Perez D. Proceedings of the 15th Annual International Symposium on Wearable Computers, ISWS 29-36. Washington DC, USA: IEEE Computer Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nehra R, Kate N, Grover S, Khehra N, Basu D. Does the excessive use of mobile phones in young adults reflect an emerging behavioral addiction? J Postgrad Med Educ Res. 2012;46:177–82. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chak K, Leung L. Shyness and locus of control as predictors of internet addiction and internet use. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7:559–70. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang L, Arkin RM. Materialism as an attempt to cope with uncertainty. Psychol Mark. 2002;19:389–406. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldberg LR. An alternative “Description of Personality”. The big-five factor structure. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59:1216–29. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.6.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.John OP, Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 102–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurven M, von Rueden C, Massenkoff M, Kaplan H, Lero Vie M. How universal is the big five? Testing the five-factor model of personality variation among forager-farmers in the Bolivian amazon. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;104:354–70. doi: 10.1037/a0030841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richins ML, Dawson S. A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. J Consumer Res. 1992;19:303–16. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richins ML. Material Values Scale: Measurement properties and development of a short form. J Consumer Res. 2004;31:209–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee EH. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2012;6:121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Block J, Kremen AM. IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:349–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Block J, Block JH. Nursery school personality and political orientation two decades later. J Res Pers. 2006;40:734–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp. 2005.09.005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farkas D, Orosz G. Ego-resiliency reloaded: A three-component model of general resiliency. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levenson H. Multidimensional locus of control in psychiatric patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1973;41:397–404. doi: 10.1037/h0035357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon M, Lee JY, Won WY, Park JW, Min JA, Hahn C, et al. Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale (SAS) PLoS One. 2013;8:e56936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demirci K, Akgönül M, Akpinar A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. J Behav Addict. 2015;4:85–92. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demírcí K, Orhan H, Demirdas A, Akpinar A, Sert H. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the smartphone addiction scale in a younger population. Bull Clini Psychopharmacol. 2014;24:226–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon M, Kim DJ, Cho H, Yang S. The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin YH, Lin YC, Lee YH, Lin PH, Lin SH, Chang LR, et al. Time distortion associated with smartphone addiction: Identifying smartphone addiction via a mobile application (App) J Psychiatr Res. 2015;65:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Groman SM, James AS, Jentsch JD. Poor response inhibition: At the nexus between substance abuse and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:690–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weafer J, Mitchell SH, de Wit H. Recent translational findings on impulsivity in relation to drug abuse. Curr Addict Rep. 2014;1:289–300. doi: 10.1007/s40429-014-0035-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goudriaan AE, Oosterlaan J, de Beurs E, van den Brink W. Neurocognitive functions in pathological gambling: A comparison with alcohol dependence, Tourette syndrome and normal controls. Addiction. 2006;101:534–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chóliz M. Mobile phone addiction: A point of issue. Addiction. 2010;105:373–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mok JY, Choi SW, Kim DJ, Choi JS, Lee J, Ahn H, et al. Latent class analysis on internet and smartphone addiction in college students. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:817–28. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S59293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.King AL, Valença AM, Nardi AE. Nomophobia: The mobile phone in panic disorder with agoraphobia: Reducing phobias or worsening of dependence? Cogn Behav Neurol. 2010;23:52–4. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e3181b7eabc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.King AL, Valença AM, Silva AC, Baczynski T, Carvalho MR, Nardi AE. Nomophobia: Dependency on virtual environments or social phobia? Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29:1404. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Billieux J, Maurage P, Lopez-Fernandez O. Can disordered mobile phone us be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Curr Addict Rep. 2015;2:156–62. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Devaraj US, Easley RF, Michael Crant J. How does personality matter? Relating the five-factor model to technology acceptance and use. Inf Syst Res. 2008;19:9105. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Landers RN, Lounsbury JW. An investigation of big five and narrow personality traits in relation to internet usage. Comput Human Behav. 2006;22:283–93. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chittaranjan G, Blom J, Gatica-Perez D. Mining large-scale smartphone data for personality studies. Pers Ubiquit Comput. 2003;17:433–50. [Google Scholar]

- 53.King L, Walker ML, Broyles SJ. Creativity and the five-factor model. J Res Pers. 1996;30:189–203. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hughes DJ, Rowe M, Batey M, Lee A. A tale of two sites: Twitter vs. Facebook and the personality predictors of social media usage. Comput Human Behav. 2012;28:561–9. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ryan T, Xenos S. Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the big five, Shyness, Narcissism, Loneliness, and Facebook usage. Comput Human Behav. 2011;27:1658–64. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tuten TL, Bosnjak M. Understanding differences in web usage: The role of need for cognition and the five factor model of personality. Soc Behav Pers. 2001;29:391–8. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Butt S, Phillips JG. Personality and self reported mobile phone use. Comput Hum Behav. 2008;24:346–60. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ross C, Orr ES, Sisic M, Arseneault JM, Simmering MG, Orr RR. Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Comput Hum Behav. 2009;25:578–86. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chorley MJ, Whitaker RM, Allen SM. Personality and location-based social networks. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;46:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Özbek V, Alnıaçık Ü, Koc F, Akkılıç ME, Kaş E. The impact of personality on technology acceptance: A study on smart phone users. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;150:541–51. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Letzring TD, Block J, Funder DC. Ego-control and ego-resiliency: Generalization of self- report scales based on personality descriptions from acquaintances, clinicians, and the self. J Res Pers. 2005;39:395–422. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong MM, Nigg JT, Zucker RA, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE, Jester JM, et al. Behavioral control and resiliency in the onset of alcohol and illicit drug use: A prospective study from preschool to adolescence. Child Dev. 2006;77:1016–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chang JH, Zhang H. Analyzing online game players: From materialism and motivation to attitude. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11:711–4. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun T, Wu G. Trait predictors of online impulsive buying tendency: A hierarchical approach. J Mark Theory Res. 2011;19:337–46. [Google Scholar]