Abstract

Background:

Internet addiction (IA) among university engineering students and its association with psychological distress can impact their educational progress, academic competence, and long-term career goals. Thus, there is a need to investigate the IA among engineering students.

Objectives:

This study was a first such attempt to explore internet use behaviors, IA, among a large group of engineering students from India, and its association with psychological distress primarily depressive symptoms.

Methods:

One thousand eighty six engineering students aged 18–21 years pursuing bachelors in engineering from the south Indian city of Mangalore participated in the study. The socio-educational and internet use behaviors data sheet was used to gather demographic information and patterns of internet use, Internet Addiction Test (IAT) was utilized to assess IA, and Self-Report Questionnaire (SRQ-20) assessed psychological distress primarily depressive symptoms.

Results:

Among the total N = 1086, 27.1% of engineering students met criterion for mild addictive internet use, 9.7% for moderate addictive internet use, and 0.4% for severe addiction to internet. IA was higher among engineering students who were male, staying in rented accommodations, accessed internet several times a day, spent more than 3 h per day on internet, and had psychological distress. Gender, duration of use, time spent per day, frequency of internet use, and psychological distress (depressive symptoms) predicted IA.

Conclusions:

A substantial proportion of engineering students have IA which can be detrimental for their educational progress in university studies and long-term career goals. Early identification and management of IA and psychological distress among engineering students is crucial.

Key words: Depressive symptoms, engineering students, internet addiction, internet use behaviors, psychological distress

INTRODUCTION

To make communication easier, quicker, and to facilitate safe exchange of information internet was developed. The use of internet in a healthy manner is defined as achieving a desired goal within an appropriate time period without experiencing intellectual or behavioral discomfort.[1]

Over the years, ever increasing use of internet for work and leisure activities has led to its omnipresent presence across all activities of the day and this has disguised the boundaries between functional and dysfunctional internet use. This manifold uses of internet such as establishing risk-free social connections with strangers, free expression of thoughts, possibility to access prohibited content, involvement in unique games, and use of numerous other functions in privacy has led to exponential rise in the use of internet.[2,3,4] Some individuals cannot control their use of internet, whereas others can limit their use. Internet addiction (IA) can be described as an individual's inability to control his or her own use of internet causing disturbances and impairment in fulfillment of work, social, and personal commitments.[5,6,7]

Research literature suggests that depression is a leading comorbid disorder with IA.[8,9] Self-esteem is one of the core components of depression.[10] It is individual's attitude to himself and it can be either negative or positive.[11] Thus, individuals with negative self-esteem are potential candidates who engage in addictive internet behaviors which helps to momentarily free themselves of their negative self-esteem, irrational cognitive assumptions, and associated unpleasant emotions.[12,13]

The occurrence of depression among the young individuals with IA and existence of IA among the depressed individuals has been observed.[14] The presence of low self-esteem, low motivation, fear of negative evaluation, social avoidance observed in depressed individuals are hypothesized to lead to excessive/addictive usage of internet in depressed individuals.[15] Social isolation caused by IA may also lead to depressive symptoms.[16]

The research evidence suggests that depression can lead to addictive use of internet and vice-versa. Thus, in both the mental health conditions have potential to influence and exacerbate each other. The objective of this study is to investigate the severity of IA, psychological distress primarily depressive symptoms, and its interrelationship among the university engineering students.

METHODS

Participants

This study had a cross-sectional study design. One thousand eighty six undergraduate engineering students aged between 18 to 21 years, studying at a recognized university, participated in the study. All these engineering students were using internet for at least 1-year duration, aged 18 years and above, were fluent in their ability to read, write, and comprehend English and gave written informed consent for the study. The study was initiated after gaining ethical approval from the ethics board of the university.

Tools

Semi-Structured Schedule

The schedule was constructed by the research team to document information about socio-demographic data and internet usage variables namely duration, frequency, devices used, time spent on internet, craving for internet use, attempts to reduce internet use, and similar other variables.

Internet Addiction Test (IAT)

It is a 20-item self-report scale based on a 5-point Likert scale to assess the IA and its severity.[17,18] The scores for the individual items were summed up for obtaining a total scale which ranges from 20 to 100. The total score was interpreted with the norm criteria of the scale which indicates mild, moderate, or severe categories of IA. Internet Addiction Test (IAT) shows good to moderate internal consistency (alpha coefficients – 0.54, −0.82). IAT has been evaluated for its content and convergent validity,[19,20,21,22] internal consistency (α = 0.88) and test–retest reliability (r = 0.82).[19] The IAT has questions like how often do you find that you stay online longer than you intended? How often do you prefer excitement of the internet to intimacy with your partner? How often do others in your life complain to you about the amount of time you spend online? How often does your work or academics suffer because of the amount of time you spend online?

Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ)

The Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ) is a 20-item self-administered tool developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) specifically for the use in developing countries for screening of mental health conditions at community settings. SRQ-20 offers a yes/no response format to the individual and is designed to identify psychological distress, inclusive of depressive symptoms and suicidality.[23] The SRQ items tap into the diagnostic categories of depressive episodes, dysthymia as defined for instance, in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10). The content validity reportedly for covering psychiatric symptoms inclusive of depressive episodes is high.[23] This study had utilized the original form of the questionnaire. The criterion validity of the Spanish version of SRQ was rs = 0.69 (N = 163)[24] and for the Portuguese version of SRQ a correlation coefficient of rs = 0.74 was obtained (N = 260).[25] The SRQ also has acceptable levels of sensitivity (62%–79%) and specificity (62%–75%) for the Indian population of psychiatric inpatients (N = 326).[26,27]

Procedure

After gaining the permission for conducting research study from the engineering college, the research assistants approached the engineering students during their free hour in the classroom setup. Each of the engineering students who gave a written informed consent for participation completed a set of the above mentioned assessment tools.

Statistical analysis

All the study data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Version 22 for Windows. Measures of central tendency and Spearman's rank correlation were used to assess the relationship among the IA and SRQ scores. Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal- Wallis tests were utilized to detect the difference among groups. Logistic Regression analysis was carried out to identify the predictors of IA. Age, gender, SRQ score, duration of internet use, average time spent on internet, and frequency of internet use were the factors which were entered in the regression equation for conducting the logistic regression analysis. The significance value for the study results has been set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample

The study sample of N = 1086 comprised of undergraduate engineering students of which 400 (36.83%) were female and 686 (63.16%) were male participants. The ages of the study sample ranged from 18 to 21 years with the median age being 20 years. More than a quarter of the sample initiated internet use each between the ages of 10 to 15 years (37.16%) and 16 to 18 years (41.64%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

The distribution of scores by socio-demographic characteristics of the sample

Internet use characteristics and IAT scores

Of the total N = 1086, 27.1% (N = 294) of engineering students met criterion on IAT for mild addictive internet use, 9.7% (N = 105) for moderate addictive internet use, and 0.4% (N = 4) for severe IA. Addictive internet use behaviors were significantly higher among male engineering students (P < 0.001). A trend towards positive correlation (rs = 0.087; P = 0.004) was observed between age and IA scores which suggests that as an individual's age increases (in this age range of 18–21 years) their risk for addictive internet use becomes higher. Engineering students who engaged in excessive/addictive use of internet were staying in rented accommodations (P = 0.015), used both laptops and mobiles (P = 0.009), spent 180 min or more in a day on internet (P < 0.001), used internet for >4 years (P < 0.001), expressed craving for use of internet (P < 0.001), and had made attempts to reduce usage of internet (P = 0.011) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of mean scores of the students on the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) according to some of the characteristics of their internet usage

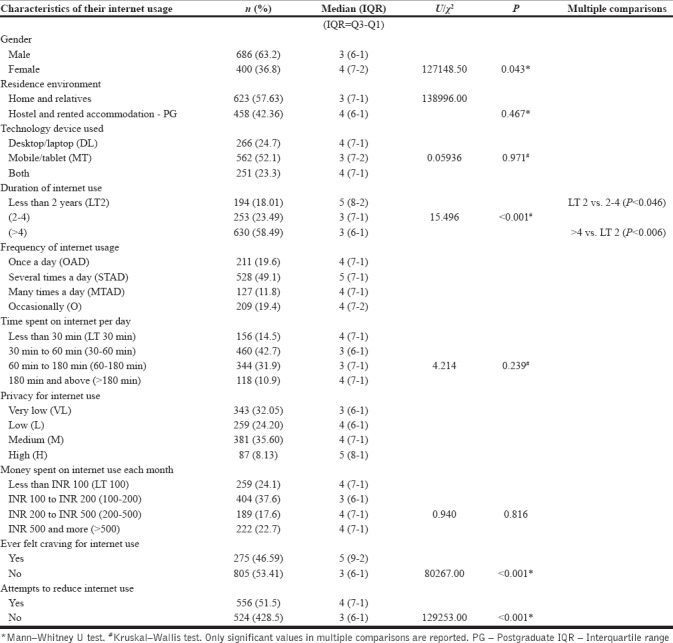

Internet use characteristics and SRQ scores

Psychological distress on SRQ was significantly higher among female engineering students (P = 0.043) and in those using internet for <2 years. Engineering students who experienced psychological distress were staying away from home in rented accommodations (P = 0.467), used both laptops and mobiles to access internet (P = 0.971), spent 180 min or more in a day on internet (P = 0.239), used internet for <2 years (P < 0.001), expressed craving for use of internet (P < 0.001), and had made attempts to reduce usage of internet (P < 0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Distribution of the mean scores of the students on the Self-Report Questionnaire (SRQ) according to some of their characteristics of internet usage

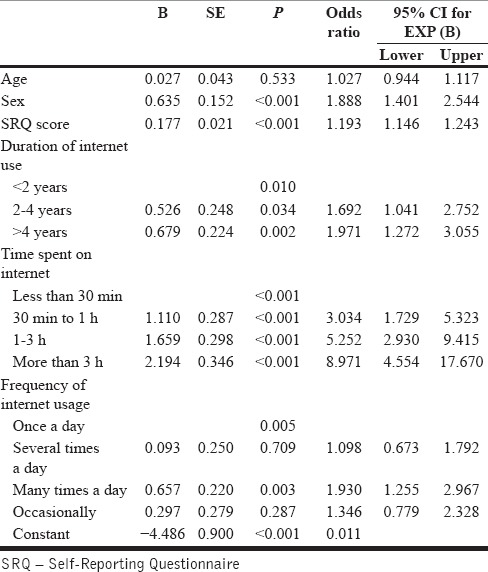

Logistic regression analysis

The logistic regression analysis indicated that engineering students who were male (odds ratio (OR) = 1.888, P < 0.001), used the internet for duration of <4 years (OR = 1.971; P = 0.002), spent >180 min in day on internet (OR = 8.971, P < 0.001), accessed internet several times a day (OR = 1.930, P = 0.003), and were experiencing psychological distress namely depressive symptoms (OR = 1.193; P < 0.001) were at higher risk for engaging in IA. The engineering students (N = 1086) attained a mean score of 4.35 (SD = 3.80) on the SRQ and 27.91 (SD = 15.94) on the IAT. A positive correlation was found between psychological distress (depressive symptoms) and IA (rs = 0.189; P < 0.001). The students who have higher SRQ scores were likely to engage in addictive use of internet. The correct classification percentage for the logistic regression analysis was found to be 70.4% [Table 4].

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis for predictors of internet addiction

DISCUSSION

IA and prevalence

The engineering students engaged in severe addictive use of internet were 0.4% and 9.7% qualified for moderate IA as per the criteria offered by IAT.[28] The present study findings on prevalence of severe IA are similar to those indicated by other studies on university students using IAT-medical (1.2%; 0.7%) and dental students (2.3%; 4.7%) from India.[29,30] The studies on undergraduate university students too have indicated a prevalence rate of severe IA ranging from 0.3% in India,[31] 2.2% in Iranian University students,[32] 2.8% in Iran medical students,[33] 5.6% in Greece,[34] 11.5% in Chile,[35] and 13.2% in Iran.[36]

The present study findings are similar to prevalence rates of moderate IA reported by other Indian studies which ranged from 7.45% in medical students,[37] to 7.4%[31] and 15.2% in university undergraduates.[38] A study from Iran indicated 8% of university students were engaged in moderate levels of IA.[32] In spite of the methodological variations among studies in terms of sample sizes, instruments used, different populations assessed across different periods of time, the prevalence of moderate to severe IA has remained fairly stable ranging from 6% to 15% across cultures. While the accessibility, availability, and cultural acceptability of internet use can be the mediating factors for the difference in results of IA prevalence, the estimates appear not too widely distributed.

IA and Socio-demographic characteristics

The regression and correlation analysis findings of the study indicate that engineering students who are comparatively elder in the study age range are at higher risk for indulging in IA. These findings are in overall agreement to those reported among university students in China.[39,40] The initial years of university education suddenly offers a shift to minimal parental control and increases opportunities for self-expression, use of self-control, and coping strategies. Those young individuals who lack self-control in context of decreased parental monitoring are at higher risk for IA.[41] This context facilitates the development of excessive internet use which with time and with repeated cycles of inappropriate internet use can reach to level of IA. Initially, internet use starts with minimal usage, and over a period of time individuals have to use it for increased amounts of time to achieve satisfaction, excitement which was experienced in initial days with reasonable duration of use (tolerance). All the offline activities of day become surrounded with the thoughts for constant connectivity to internet, for the pleasurable feelings it created when they used internet the last time (salience), and a constant desire to use internet throughout the day (craving). Upon inability to access internet, it causes mood changes, restlessness, anxiety, behavioral inactivity, or increased attempts to get back the internet access (withdrawal). Excessive internet use can also lead to outcomes (consequences) as decline in performance in academics, at work, and in social interactions. IA appears to share similarities with addictive use of alcohol in terms of progression of addictive behaviors.

Our study indicated that IA behaviors were significantly higher among male engineering students in comparison to female engineering students (P = <0.001). In our study, male gender also predicted IA. The present study finding is similar to other studies results from India.[31,42] Studies conducted in Iran[32], Greece,[43] and Taiwan[44] also reveal similar findings with respect to gender differences. Vulnerability of male gender to IA is supported by the findings of meta analytic research of studies conducted between 1996 and 2006.[45] It can be understood that there is a higher involvement of males in internet chatting, online gaming, online gambling, virtual sex, pornography since socialization offers lesser restriction to males in a majority of cultural contexts[40,46,47,48,49,50] which increases the likelihood of males becoming addicted to internet. The potential risk for IA for males in comparison to females increases since males are apparently more efficient at using internet, its applications, bypassing firewalls, installing and removing programs, applications, overcoming internet access-related problems, receive lesser supervision by parents, and thus end up using internet more for entertainment needs.[51]

Engineering students were staying away from their families, in rented accommodations were at a higher risk of developing IA. This study finding is in alignment with studies done in India[37] and Iran[51] which too suggested IA is higher among students who stay independently. The experience of loneliness, boredom, availability of privacy, ease of internet access, and minimal presence of parental supervision are factors which likely increase excessive use of internet. This presence of these factors offer an environment which has the potential to facilitate the development of excessive internet use which with time and with repeated cycles of inappropriate internet use can reach to level of IA.

IA and internet use characteristics

The amount of time an individual spends on internet is a crucial factor which increases risk of IA. Our study results indicate that engineering students who were engaging in >3 h of internet use per day in non-academic internet activities had higher levels of IA (P = <0.001). Our study revealed that time spent on internet per day and frequencies of internet use were variables which predicted IA. The research evidence from many studies consistently suggests that the severity levels of IA increase with increasing duration of internet use.[47,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] Thus, findings apparently imply that risk of becoming addicted to internet becomes higher when the time students spend on internet use becomes greater.

Engineering students who accessed internet several times a day (P = <0.001) and remained online throughout the day also had higher levels of IA. Another study from India[59] corroborated with the findings of the present study. Those with higher levels of IA were using both mobiles and computer tablets as it offers easy accessibility, affordability, and connectivity across situations throughout the day.

Our study also indicates that students who had higher levels of IA scores were using internet for >4 years and the duration of use was a variable which predicted IA. Duration of internet use was also predictor for IA among university students in Turkey.[60] In our sample 58.49% of engineering students had internet use of 4 years and above. However, this finding does not necessarily highlight the time duration required for emergence of IA since its initial use by the individual. Another study conducted in India suggested time duration of 6 years between first use and development of IA.[61] However, this time duration may steadily reduce over the years with the increase in accessibility of internet at cheaper rates in India. About 53.9% engineering students who knew about IA had made attempts to reduce IA. This indicates that awareness about IA among students will be a first initial step towards healthy use of technology.

IA and psychological distress

The presence of psychological distress appears to be a significant factor which has the potential to increase the risk of IA. Regression analysis indicated engineering students who had psychological distress (depressive symptoms) predicted IA or were at risk for engaging in IA behaviors. The correlation between depressive symptoms and IA observed in this study has been reported by other studies.[1,50,53,62,63,64,65,66] It is to be observed that a noticeable proportion of the present study sample 2% (N = 22) had in the recent past approached a mental health professional for excessive internet use.

The starting of an undergraduate course in engineering brings with itself a set of challenges and a phase of transition in academic life. Along with this transition students need to solve everyday challenges of staying away from home, study well, form new interpersonal relationships, and gather social and emotional support. Vulnerable individuals can experience boredom, loneliness, and depressive symptoms during this phase of transition.

In this context, internet can be viewed by some individuals as a medium to cope up with the psychological distress caused by the new challenges. To establish new interpersonal relationships, seek information, guidance, and for entertainment internet can be used by students. However, the risk for IA increases with excessive use of internet which has potential to cause depressive symptoms. The individuals who are predisposed to depression or are experiencing depressive symptoms are engaging in addictive use of internet.[40,67,68] Individuals with depressive symptoms understandably experience loneliness, low self-esteem, decreased energy, and lack of motivation[63,69] which likely drives them to use internet to overcome these unpleasant emotions. Gaining of social approval, enhancement of self-esteem, and overcoming of loneliness can be achieved via the internet.[70] On the contrary, an individual who starts diverting time meant for social meetings, outdoor activities, and family events towards internet use ends up isolating oneself and predisposes oneself towards depressive symptoms.[71] Thus, both IA and depressive symptomatology can interact with each other and exacerbate both psychological conditions.[40,67,68]

CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS

In India, IA appears to be a significant emerging mental health condition among university engineering students. Psychological distress (depressive symptoms) and IA were positively correlated and it is a variable which is associated with IA. Engineering students must be screened for psychological distress and IA as there is a high possibility that they coexist and can intensify each other. Initiation of such efforts will help in offering early referrals to specialized centers for accurate identification and treatment. About 53.9% engineering students who knew about IA had made attempts to reduce IA. Thus, awareness creation about IA and its risk factors among students and faculty will be a useful initial step towards healthy use of internet. Studies in future can explore relationship of IA and depressive symptoms in a prospective design.

Highlights of the research study findings

Among the N = 1086, 27.1% (N = 294) of engineering students met criterion on IAT for mild addictive internet use, 9.7% (N = 105) for moderate addictive internet use, and 0.4% (N = 4) for severe internet addiction.

IA appears to be a major emerging public mental health condition among young adults in India.

IA was higher among university engineering students who were male, staying in rented accommodations, accessed internet several times a day, spent <3 h per day on internet and had psychological distress.

Male gender, duration of use, time spent per day, frequency of internet use, and psychological distress (depression) predicted IA.

Psychological distress (depression) and IA were positively correlated and it is a variable which predicts IA. Thus, it is suggested that engineering students must be screened for psychological distress and IA as there is a high possibility that they coexist and exacerbate each other.

About 53.9% engineering students who knew about IA had made attempts to reduce IA. Thus, awareness creation about IA and its risk factors among students and faculty will surely be a useful initial step towards healthy use of internet.

Early identification and management of IA and psychological distress among engineering students is crucial. Initiation of such efforts will help in offering referrals to advanced centers for accurate identification and treatment.

Contributors

All the authors involved in conception, design, collection of data, interpretation of data, drafting the article, and final approval of the version to be published.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davis RA, Flett GL, Besser A. Validation of a new scale for measuring problematic internet use: Implications for pre-employment screening. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2002;5:331–45. doi: 10.1089/109493102760275581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingstone SM, Lievrouw LA. Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs. Sage. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teo TS, Lim VK. Gender differences in internet usage and task preferences. Behav Inform Techn. 2000;19:283–95. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young KS. Internet addiction: Symptoms, evaluation and treatment. In: VandeCreek L, Jackson T, editors. Innovations in Clinical Practice: A Source Book. 2018. Vol. 17. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 1999. pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen K, Tarn JM, Han BT. Internet dependency: Its impact on online behavioral patterns in E-commerce. Hum Syst Manage. 2004;23:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young KS. Internet addiction: A new clinical phenomenon and its consequences. Am Behav Sci. 2004;48:402–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanton JM. Company profile of the frequent internet user. Communications of the ACM. 2002;45:55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carli V, Durkee T, Wasserman D, Hadlaczky G, Despalins R, Kramarz E, et al. The association between pathological internet use and comorbid psychopathology: A systematic review. Psychopathology. 2013;46:1–13. doi: 10.1159/000337971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yen J-Y, Ko C-H, Yen C-F, Wu H-Y, Yang M-J. The comorbid psychiatric symptoms of internet addiction: Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, social phobia, and hostility. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fennell MJ. Low self-esteem: A cognitive perspective. Behav Cogn Psychother. 1997;25:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg M. The measurement of self-esteem, society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton. 1965:16–36. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert JC. The role of personality in understanding substance abuse. Alcohol Treat Q. 1995;13:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffiths M. Does internet and computer “addiction” exist? Some case study evidence. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2000;3:211–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yen JY, Ko CH, Yen CF, Wu HY, Yang MJ. The comorbid psychiatric symptoms of internet addiction: Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, social phobia, and hostility. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang CK, Choe BM, Baity M, Lee JH, Cho JS. SCL-90-R and 16PF profiles of senior high school students with excessive internet use. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50:407–14. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai CC, Lin SS. Internet addiction of adolescents in Taiwan: An interview study. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2003;6:649–52. doi: 10.1089/109493103322725432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young KS. Caught In The Net: How To Recognize The Signs Of Internet Addiction--And A Winning Strategy For Recovery: John Wiley & Sons. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Widyanto L, McMurran M. The psychometric properties of the internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7:443–50. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alavi SS, Eslami M, Meracy M, Najafi M, Jannatifard F, Rezapour H. Psychometric properties of young Internet Addiction Test. Int J Behav Scien. 2010;4:183–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang MK, Law SPM. Factor structure for young's Internet Addiction Test: A confirmatory study. Comput Hum Behav. 2008;24:2597–619. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fioravanti G, Primi C, Casale S. Psychometric evaluation of the generalized problematic internet use scale 2 in an Italian sample. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16:761–6. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korkeila J, Kaarlas S, Jääskeläinen M, Vahlberg T, Taiminen T. Attached to the web—harmful use of the internet and its correlates. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25:236–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beusenberg M, Orley JH. A user's guide to the self reporting questionnaire (SRQ) 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Araya R, Wynn R, Lewis G. Comparison of two self administered psychiatric questionnaires (GHQ-12 and SRQ-20) in primary care in Chile. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27:168–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00789001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mari JDJ, Williams P. A comparison of the validity of two psychiatric screening questionnaires (GHQ-12 and SRQ-20) in Brazil, using relative operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Psychol Med. 1985;15:651–9. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700031500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deshpande SN, Sundaram K, Wig N. Psychiatric disorders among medical in-patients in an Indian hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:504–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sen B, Wilkinson G, Mari J. Psychiatric morbidity in primary health care a two-stage screening procedure in developing countries: Choice of instruments and cost-effectiveness. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:33–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young KS. Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;1:237–44. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gedam SR, Shivji IA, Goyal A, Modi L, Ghosh S. Comparison of internet addiction, pattern and psychopathology between medical and dental students. Asian J Psychiatry. 2016;22:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain T, Mohan Y, Surekha S, Mouna VS, Swapna US, Swathy Y, et al. Prevalence of internet overuse among undergraduate students of a private university in south India. Int J Rec Tren Scien Tech. 2014;11:301–4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma A, Sahu R, Kasar PK, Sharma R. Internet addiction among professional courses students: A study from central India. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2014;3:1069–73. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bahrainian SA, Alizadeh KH, Raeisoon MR, Gorji OH, Khazaee A. Relationship of internet addiction with self-esteem and depression in university students. J Prev Med Hyg. 2014;55:86–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghamari F, Mohammadbeigi A, Mohammadsalehi N, Hashiani AA. Internet addiction and modeling its risk factors in medical students, Iran. Indian J Psychol Med. 2011;33:158–62. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.92068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsimtsiou Z, Haidich AB, Spachos D, Kokkali S, Bamidis P, Dardavesis T, et al. Internet addiction in Greek medical students: An online survey. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39:300–4. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berner JE, Santander J, Contreras AM, Gómez T. Description of internet addiction among Chilean medical students: A cross-sectional study. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38:11–4. doi: 10.1007/s40596-013-0022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fallahi V. Effects of ICT on the youth: A study about the relationship between internet usage and social isolation among Iranian students. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2011;15:394–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaudhari B, Menon P, Saldanha D, Tewari A, Bhattacharya L. Internet addiction and its determinants among medical students. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015;24:158–62. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.181729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paul A, Ganapthi C, Duraimurugan M, Abirami V, Reji E. Internet addiction and associated factors: A study among college students in south India. Open J Psychiatry Allied Sci. 2015;5:121–5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ni X, Yan H, Chen S, Liu Z. Factors influencing internet addiction in a sample of Freshmen University students in China. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12:327–30. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang W. Internet dependency and psychosocial maturity among college students. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2001;55:919–38. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee S. Doctor Dissertation. Austin: University of Texas; 2009. Problematic internet use among college students: An exploratory survey research study. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goel D, Subramanyam A, Kamath R. A study on the prevalence of internet addiction and its association with psychopathology in Indian adolescents. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:140–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.111451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frangos CC, Fragkos KC, Kiohos A. Internet addiction among Greek university students: Demographic associations with the phenomenon, using the Greek version of young's Internet Addiction Test. Int J Eco Sci App Res. 2010;3:49–74. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai HF, Cheng SH, Yeh TL, Yang YK. The risk factors of internet addiction—a survey of university freshmen. Psychiatry Res. 2009;167:294–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Byun S, Ruffini C, Mills JE, Douglas AC, Niang M, Stepchenkova S, et al. Internet addiction: Metasynthesis of 1996–2006 quantitative research. CyberPsychol Behav. 2009;12:203–7. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Batigun AD, Kilic N. The relationships between internet addiction, social support, psychological symptoms and some socio-demographical variables. Turk Psikoloji Dergisi. 2011;26:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morahan-Martin J, Schumacher P. Incidence and correlates of pathological internet use among college students. Comput Hum Behav. 2000;16:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim K, Ryu E, Chon MY, Yeun EJ, Choi SY, Seo JS, et al. Internet addiction in Korean adolescents and its relation to depression and suicidal ideation: A questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43:185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang SC, Tung C-J. Comparison of internet addicts and non-addicts in Taiwanese high school. Comput Hum Behav. 2007;23:79–96. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ko C-H, Yen J-Y, Chen C-S, Chen C-C, Yen C-F. Psychiatric comorbidity of internet addiction in college students: An interview study. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:147–53. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900016308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asiri S, Fallahi F, Ghanbari A, Kazemnejad-leili E. Internet addiction and its predictors in guilan medical sciences students, 2012. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2013;2:234–9. doi: 10.5812/nms.11626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beard KW, Wolf EM. Modification in the proposed diagnostic criteria for internet addiction. CyberPsychol Behav. 2001;4:377–83. doi: 10.1089/109493101300210286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keser-Özcan N, Buzlu S. Problemli internet kullanımını belirlemede yardımcı bir araç: “internette bilişsel durum ölçeği” nin üniversite öğrencilerinde geçerlik ve güvenirliği. Bağımlılık Dergisi. 2005;6:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Treuer T, Fábián Z, Füredi J. Internet addiction associated with features of impulse control disorder: Is it a real psychiatric disorder? J Affect Disord. 2001;66:283. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ceyhan E, Ceyhan AA, Gürcan A. Problemli internet kullanımı ölçeğinin geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışmaları. Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi. 2007;7:387–416. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chou C, Hsiao M-C. Internet addiction, usage, gratification, and pleasure experience: The Taiwan college students' case. Comput Educ. 2000;35:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salehi M, Khalili MN, Hojjat SK, Salehi M, Danesh A. Prevalence of internet addiction and associated factors among medical students from Mashhad, Iran in 2013. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:5–12. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.17256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boonvisudhi T, Kuladee S. Association between internet addiction and depression in Thai medical students at Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital. PloS One. 2017;12:e0174209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krishnamurthy S, Chetlapalli SK. Internet addiction: Prevalence and risk factors: A cross-sectional study among college students in Bengaluru, the Silicon Valley of India. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59:115–21. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.157531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Şenormancı Ö, Saraçlı Ö, Atasoy N, Şenormancı G, Koktürk F, Atik L. Relationship of internet addiction with cognitive style, personality, and depression in university students. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:1385–90. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grover S, Chakraborty K, Basu D. Pattern of internet use among professionals in India: Critical look at a surprising survey result. Ind Psychiatry J. 2010;19:94–100. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.90338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ha JH, Yoo HJ, Cho IH, Chin B, Shin D, Kim JH. Psychiatric comorbidity assessed in Korean children and adolescents who screen positive for internet addiction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:821–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ko C-H, Yen J-Y, Chen C-C, Chen S-H, Yen C-F. Gender differences and related factors affecting online gaming addiction among Taiwanese adolescents. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193:273–7. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000158373.85150.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bernardi S, Pallanti S. Internet addiction: A descriptive clinical study focusing on comorbidities and dissociative symptoms. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:510–6. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim K, Ryu E, Chon MY, Yeun EJ, Choi SY, Seo JS, et al. Internet addiction in Korean adolescents and its relation to depression and suicidal ideation: A questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43:185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ho RC, Zhang MW, Tsang TY, Toh AH, Pan F, Lu Y, et al. The association between internet addiction and psychiatric co-morbidity: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:183–92. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Facer K, Sutherland R, Furlong R, Furlong J. What's the point of using computers? The development of young people's computer expertise in the home. New Media Soc. 2001;3:199–219. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsai C-C, Lin SS. Internet addiction of adolescents in Taiwan: An interview study. CyberPsychol Behav. 2003;6:649–52. doi: 10.1089/109493103322725432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kraut R, Patterson M, Lundmark V, Kiesler S, Mukophadhyay T, Scherlis W. Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am Psychol. 1998;53:1017–31. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wartberg L, Sack P-M, Petersen K-U, Thomasius R. Psychopathology and achievement motivation in adolescents with pathological internet use. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie. 2011;60:719–34. doi: 10.13109/prkk.2011.60.9.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Young KS, Rogers RC. The relationship between depression and internet addiction. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;1:25–8. [Google Scholar]